Abstract

We have recently found that 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, a synthetic iminosugar exerting glucosidase inhibitory activity, but not its natural enantiomer lentiginosine, is endowed with an unexpected, pro-apoptotic activity. Here, we investigated mechanisms involved in apoptosis induced by 𝒟−)lentiginosine in MOLT-3, HT-29 and SH-SY5Y tumour cell lines. The results showed that 𝒟−)lentiginosine increased caspase 9 expression at 18 h in all the cell lines from 1.5–3.1 folds. Cytochrome c in the cytoplasm was found to be increased from 2.3–2.6 folds in treated cells with respect to control cells. These effects were accompanied by a remarkable collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential and by the downregulation of anti-apoptotic genes, as well as the upregulation of pro-apoptotic genes of the Bcl-2 family. U937Bcl-2 transfectants, highly expressing Bcl-2, were reluctant to undergo apoptosis even following treatment with 500 μM 𝒟−)lentiginosine, whereas apoptosis by 𝒟−)lentiginosine was induced also in U937 cells, naturally deficient in P53. Thus, our study establishes that the enantiomer of a natural iminosugar is endowed with a possible anti-tumorigenic effect that might be ascribed not only to their capacity to inhibit glycosidases but also to other unknown mechanisms. These data encourage further investigation on similar compounds to make them an interesting platform for the generation of new anticancer drugs.

Keywords: iminosugar, 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, apoptosis, mitochondrion, Bcl-2

Glycosidases are an important class of enzymes involved in the processing of oligosaccharide units both on proteins and lipids. A number of intracellular processes involving intestinal digestion, post-translational modification of nascent glycoproteins, lysosomal catabolism of glycoconjugates and inter-cellular recognition events are led by glycosidases.1 In particular, glycosidases are involved in the processing of carbohydrate moieties that is a critical step for creating intermediate glycan structures able to bind proteins. Within the class of glycosidases, glucosidases share their ability to specifically hydrolyse different glucosaccharides.2 Inhibitors of glycosidase processing disturb physiological protein folding and intracellular transport, potentially leading to cell damage and eventually death of the host cell by necrosis or apoptosis. Several natural and synthetic compounds are able to inhibit glycosidase activity. Tea flavonoids, such as (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, have been recently shown to induce apoptosis in mouse hepatoma cells by interfering with protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum,3, 4 presumably due to inhibition of glucosidase II.5 Several iminosugars, both natural and synthetically derived, have been shown to inhibit specific glycosidases and have been used as a therapeutic tool in several diseases.6 Iminosugars were used in metabolic disorders characterized by the accumulation of glycosphingolipids in lysosomes, because of the deficient activity of glycosidases.7 In particular N-butyl-1-deoxynojirimycin has been used to treat type 1 Gaucher diseases characterized by glucocerebroside accumulation,8 whereas α-glucosidase inhibitors were used to treat type-2 diabetes mellitus.9 However, inhibition of carbohydrate-processing enzymes by iminosugars also affects maturation, transport and secretion of glycoproteins involved in cell to cell contact. These biological aspects are of fundamental importance in determining tumour transformation and metastasis.10 Recently, iminosugars have been utilized in vivo in B16 melanoma and 3LL lung carcinoma to suppress metastasis in the murine experimental model.11 The antitumour activity of N-alkylated derivatives of a naturally occurring iminosugar 𝒟-fagomine on tumour cells of different origins was analysed in vitro. The results showed that the cytotoxic effect of these compounds was dependent on the length of the alkyl groups attached to the iminosugars and paralleled the inhibitory activity of glycosidases.7 Moreover, castanospermine, an iminosugar endowed with α-glucosidase inhibitor activity, was shown to inhibit the migration and invasion tendency of tumour cells, preventing them from binding to extracellular matrix.12, 13 These lines of evidence suggest that iminosugars are endowed with a broad range of biological activity potentially useful in therapeutic treatment. Moreover, even if the capacity of iminosugars to act as glycosidase inhibitors has been widely documented, the pleiotropic biological effects of these compounds might be ascribed to other mechanisms.6

A previous study from our laboratories demonstrated for the first time that the non-natural enantiomer of lentiginosine,14 that is, 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, an iminosugar endowed with a mild glucosidase inhibitory activity, and its derivative (−)-7S-OH-lentiginosine were able to induce apoptosis in cells of different origin.15, 16

Apoptosis, the most well-characterized form of programmed cell death, has critical roles in normal and pathological states, including cancer. It can be triggered by a variety of physiological and pathological stimuli, including the engagement of death receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor receptor family on the cell surface or of intracellular signals that act upon the Bcl-2 protein family.17 Thus, cell death by apoptosis is routed through two main pathways: the extrinsic and the intrinsic pathways. The extrinsic pathway is receptor-dependent, whereas the intrinsic one is activated by intracellular events and depends on the release of pro-apoptotic factors from the mitochondria. Mitochondrial apoptosis involves important changes in membrane permeability accompanied by the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial intermembranous space, apoptosis-inducing factor, second mitochondrial activator of caspases and ultimately activation of caspases, such as caspases 9, 8 and 3.18 The protection of the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane is afforded by the complex of Bcl-2 proteins, whose expression regulate the intrinsic apoptosis route. It is known that the Bcl-2 family has a key role in determining cell death through mitochondria. The anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family includes Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bcl-w, all of which contain BH 1–4 domains. The pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family of proteins present a number of BH domains (Bax, Bak and Box) or have only the BH3 domain, such as Bid, Bim, Bad, Puma and Noxa.19 The turnover of the BH3 domain-only proteins is critical to determine the cell death and influence the balance with the pro-survival Bcl-2 proteins.20 It is generally accepted that the majority of cytotoxic, anticancer drugs induce apoptosis by the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 intrinsic pathway.21 In this study, we investigated the mechanism underlying the pro-apoptotic activity of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. In particular, we seek to ascertain whether the caspase cascade triggered in tumour cells of different origin by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine was due to signalling belonging to the mitochondria-associated pathway.

Results

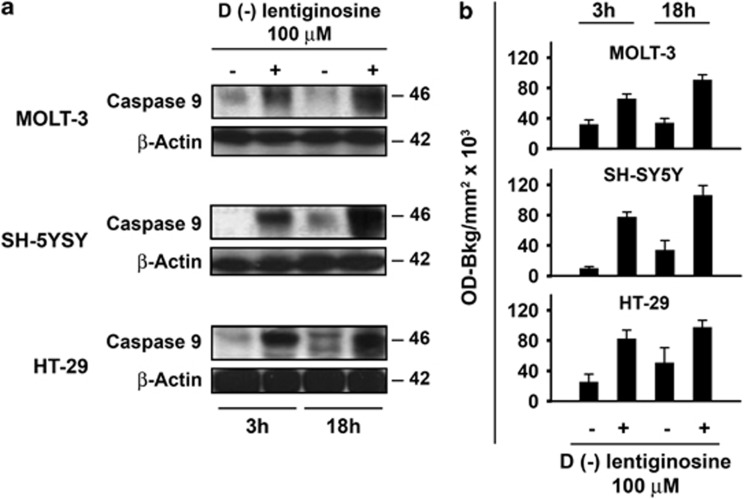

Evaluation of caspase 9 expression

Initially, we considered whether 𝒟(−) lentiginosine, in addition to inducing the expression and activation of caspase 8 and 3 (Macchi et al.16), was also able to induce expression of caspase 9, one of the key enzymes of the intrinsic pathway. To this purpose, the different cell lines were preliminarily subjected to dose-effect experiments, to ascertain their susceptibility to apoptosis following 18 h of treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, as expected by our previous studies. In fact, the percentage of hypodiploid nuclei, as assayed by propidium iodide staining, ranged from 50% for MOLT-3 and HT-29 cells to 20% for SH-SY5Y cells following treatment with 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine (data not shown). We chose 100 μM as a suitable concentration to study the effect of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine on signalling involved in the apoptotic intrinsic pathway. Caspase 9 expression was assessed through immunoblot analysis in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells after treatment with 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 3 and 18 h (Figure 1). Figure 1, panel a, shows western blots obtained in one representative experiment of the three independent performed. Caspase 9 was clearly induced after 3 h of treatment and further increased after 18 h. Densitometry analysis of western blots provides quantitative results shown in panel b of Figure 1, where cumulative values of the three experiments are expressed as OD-Bkg/mm2 × 103 (mean±S.D.) with respect to control cells. Expression of caspase 9 was highly significantly increased in all cell lines assayed in comparison with control cells as early as after 3 h of treatment. After 18 h of treatment, caspase 9 expression was further increased in all cell lines. A noticeable, but not statistically significant, increase in caspase 9 expression was also observed in SH-SY5Y and HT-29 control cells kept in culture for 18 h in comparison with those kept in culture for 3 h.

Figure 1.

Expression of caspase 9. (a) The expression of caspase 9 was assessed by western blot analysis after 3 and 18 h of treatment. MOLT-3, SHSY-5Y and HT-29 cells were treated with 0 and 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. One experiment representative of the three independent experiments performed is shown. β-actin expression, run on the same gel, indicates that an equal amount of protein was loaded for each sample. (b) Western blot analysis for each sample was quantified by densitometry analysis and values were expressed as OD-Bkg/mm2 × 103. Histograms represent mean values±S.D. from the three independent experiments performed on MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells. Statistical comparison of means using the Bonferroni's post-hoc multiple comparison analysis of variance (ANOVA) test provided the following results. MOLT-3: control 3 h versus control 18 h, not significant (NS); treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P=0.001; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P <0.001. SH-SY5Y: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P <0.001; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P <0.001. HT-29: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P=0.005; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P=0.015

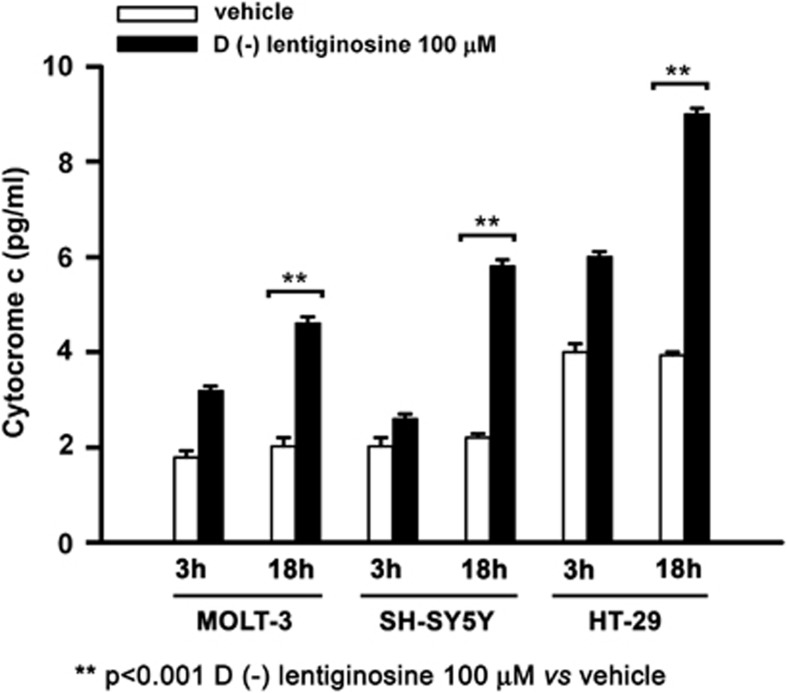

Cytochrome-c release

We then decided to investigate the apical signalling known to control caspase 9 activation. One main regulator of caspase 9 activation is cytochrome c. We measured the release of cytochrome c following treatment of MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine at 100 μM for 3 and 18 h. Cytochrome-c production was assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the results are shown in Figure 2. The results are the cumulative mean values of three independent experiments. After 3 h of treatment, a noticeable, but not significant, increase in cytochrome c occurred in all the three cell lines. After 18 h of treatment the release of cytochrome c was highly significantly increased by 2.3 folds in MOLT-3 and HT-29 cells and by 2.6 folds in SH-SY5Y cells, respectively, in comparison with respective control cells.

Figure 2.

Quantitative detection of cytochrome c in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells. The cells were treated with 0 and 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 3 and 18 h, assayed by ELISA. The data are represented as mean values±S.D. of three independent experiments. Asterisks (**P <0.001) indicate highly significant differences between treated and control cells

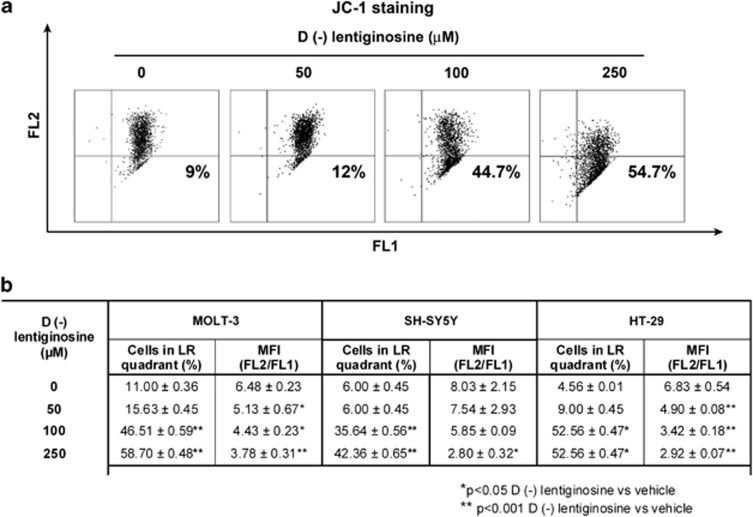

Effects on mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Cytochrome c is released following alteration of the MMP. Thus, we investigated changes in the MMP in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells treated with a control vehicle or 50, 100 and 250 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 18 h. The collapse of MMP mirrors precocious events at the mitochondrial level, leading to cell death by apoptosis. The collapse of MMP was detected by using the cationic dye JC-1 (5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide). If the mitochondrial potential collapses, a higher number of monomeric JC-1, low-red fluorescent forms accumulate in the cytoplasm. Thus, the percentage of monomeric JC-1-positive cells in the presence of different 𝒟(−)lentiginosine concentrations reflects cells routed to apoptosis. Panel a of Figure 3 shows a representative dot plot analysis of JC-1-stained MOLT-3 cells. Vehicle-treated cells exhibit high levels of both red (FL2) and green (FL1) fluorescence, whereas treated samples show a progressive decrease of high-red fluorescent aggregates and an accumulation of cells positive for the monomeric forms of JC-1 in the lower right (LR) quadrant of the cytogram. Data in panel b of Figure 3 represent cumulative results from the three independent experiments performed for each cell line. Results are expressed as mean values±S.D. of % cells accumulated in the LR quadrant, as well as of red/green, mean fluorescence intensity, ratios. The results show that the percentage of monomeric JC-1-positive cells increased progressively in a dose-dependent manner, after 18 h of treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. Mean values of cells in the LR quadrant showed a high significant increase at 100 and 250 μM, in comparison with vehicle-treated cells, for all cell lines tested. Moreover, coherent with a dose-dependent MMP collapse, values of red/green mean fluorescence ratios progressively decreased following treatment with increasing concentrations of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine in all cell lines assayed.

Figure 3.

Detection of the MMP (Δψm) in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells. (a) A representative dot plot analysis of Δψm in MOLT-3 cells. The cells were treated with 0, 50, 100 and 250 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 18 h. Cells were stained with JC-1 for 15 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2, washed with PBS and analysed on a flow cytometer. Percentage numbers indicate aggregates accumulated in the LR quadrant of the cytogram. (b) Cumulative results from three independent experiments for each cell line assayed. Data are expressed as mean values±S.D. of % cells accumulated in the LR quadrant and of corresponding ratios of red/green (FL2/FL1) mean fluorescence intensity. Asterisks indicate significant (*P <0.05) or highly significant (**P <0.001) difference between treated and control cells

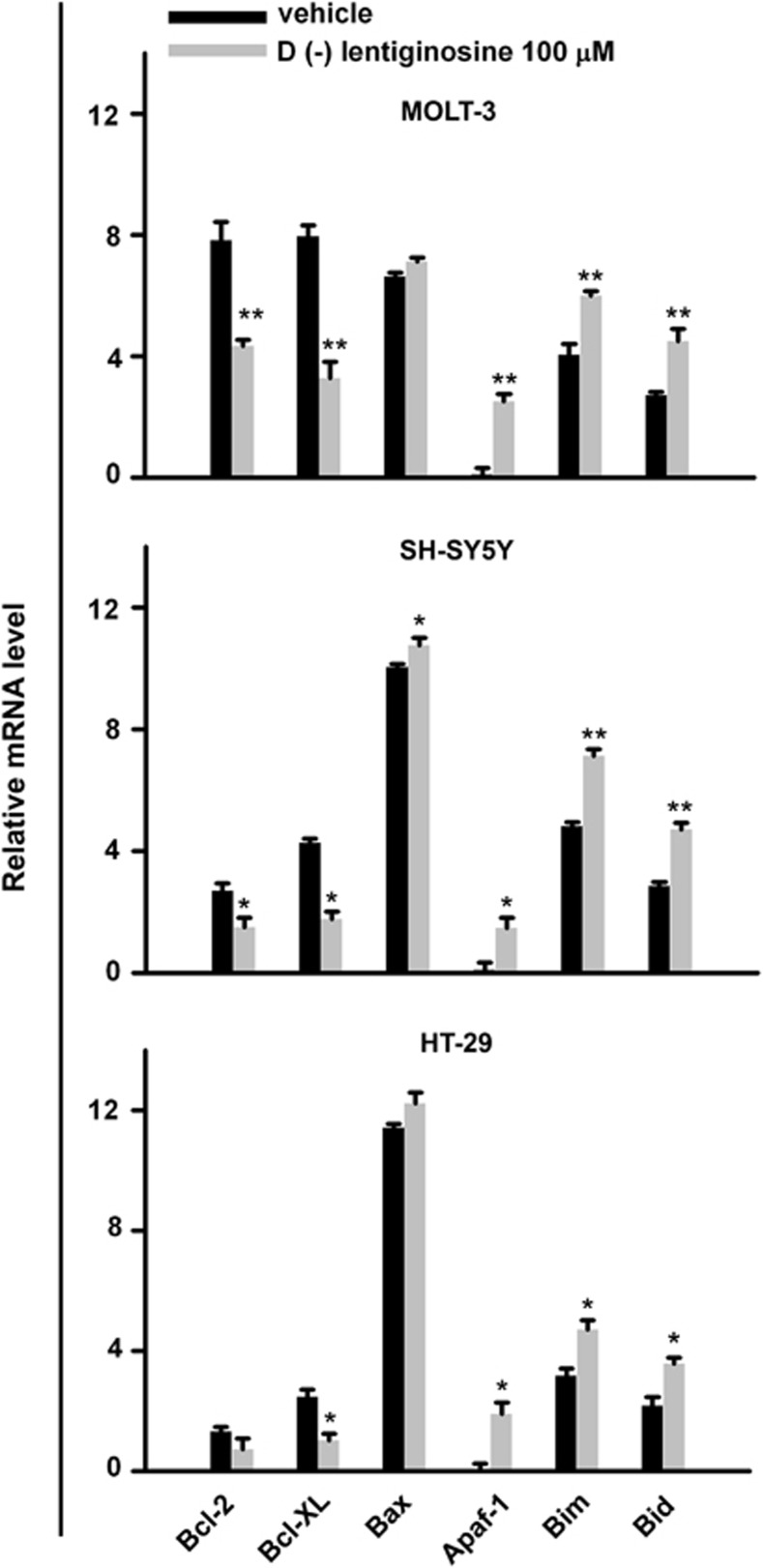

Analysis of mitochondria-associated Bcl-2 family gene expression through real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RQ-PCR)

The MMP-dependent release of cytochrome c and consequent caspase 9 activation are regulated by modulation of genes belonging to the Bcl-2 family. Thus, we investigated the expression of both pro- and anti-apoptotic genes of this family in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells following treatment with 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 18 h. Figure 4 shows a quantitative analysis of gene transcripts through real-time PCR, following normalization with the housekeeping gene GUSB. The results represent the mean values of triplicate samples and are expressed as fold changes with respect to the least expressed gene, that is, APAF-1, in control samples. Analysis revealed modulation of both pro- and anti-apoptotic genes of the Bcl-2 gene family following treatment with the compound. In particular, the anti-apoptotic gene BCL-2 was significantly inhibited in MOLT-3- and SH-SY5Y-treated cells (MOLT-3, P<0.001; SH-SY5Y, P<0.05), whereas BCL-XL was significantly inhibited in all the three cell lines tested (MOLT-3, P<0.001; SH-SY5Y and HT-29, P<0.05). Among the pro-apoptotic genes, BAX was slightly, but not significantly, upregulated with respect to the control, whereas APAF-1, BIM and BID were significantly upregulated in MOLT-3 and HT-29 cells (MOLT-3, P<0.001; HT-29, P<0.05). In addition, BIM and BID showed a high, significant upregulation in SH-SY5Y cells. Thus, it seems that 𝒟(−)lentiginosine induced cytochrome c release and activation of caspase 9 mainly through the downregulation of BCL-2 and BCL-XL and upregulation of BIM and BID gene expression.

Figure 4.

Real-time analysis of Bcl-2 family gene transcripts. BCL-2, BCL-XL, BAX, APAF-1, BIM and BID expression was assessed after treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine 100 μM for 18 h in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells. The histograms represent mean values±S.D. from triplicate samples and are expressed as fold change in mRNA levels with respect to the less expressed gene, following normalization with an housekeeping gene. Asterisks indicate significant difference between treated and control cells, (*P <0.05 and **P <0.001)

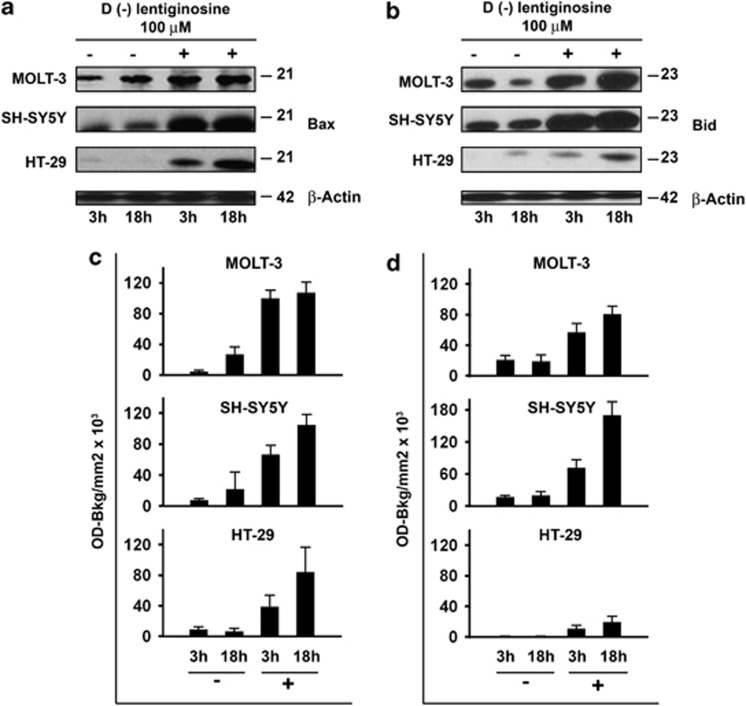

Immunoblot analysis of pro-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family

On the basis of the data obtained through RQ-PCR, we decided to assess the modulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family by choosing an upstream activated pro-apoptotic protein, Bid, and a downstream target, such as Bax, in MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells following treatment with 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 3 and 18 h. Western blot analysis showed that although the constitutive expression of Bax and Bid was variable in the different cell lines at different times, the same proteins were invariably upregulated, starting from as early as 3 h after treatment, by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine (Figure 5, panels a and b, one representative experiment of the three performed). In Figure 5, panels c and d, the cumulative results of the quantitative analysis from three independent experiments on Bax and Bid expression, respectively, are reported. Results are expressed as means±S.D. OD-Bkg/mm2 × 103 obtained from the densitometric analysis of the immunoblots. In particular, these data indicate slight, but not statistically significant, changes regarding to both Bax and Bid expression in vehicle-treated control cells kept in culture for 18 h in comparison with those kept in culture for 3 h, in all cell lines. Conversely, expression of Bax and Bid in 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-treated cells was significantly or highly significantly increased with respect to corresponding control cultures in all cell lines assayed after 3 h as well after 18 h in cultures, except for HT-29 cells after 3 h of treatment. Indeed, Bax and Bid proteins were well detectable by western blot analysis in the latter cell line only after treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine.

Figure 5.

Detection of Bax and Bid protein expression. (a) The expression of Bax was assessed by western blot analysis after 3 and 18 h of treatment. MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells were treated with vehicle or 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. One experiment representative of the three independent experiments performed is shown. β-actin expression, run on the same gel, indicates that an equal amount of protein was loaded for each sample. (b) The expression of Bid was assessed by western blot analysis after 3 and 18 h of treatment. MOLT-3, SH-SY5Y and HT-29 cells were treated with vehicle or 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. One experiment representative of the three independent experiments performed is shown. β-actin expression, run on the same gel, indicates that an equal amount of protein was loaded for each sample. (c) Western blot analysis of Bax expression was quantified by densitometry analysis and values were expressed as OD-Bkg/mm2 × 103. Histograms represent mean values±S.D. from the three independent experiments performed on each cell line. Statistical comparison of means using the the Bonferroni's post-hoc multiple comparison ANOVA test provided the following results. MOLT-3: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P <0.001; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P <0.001. SH-SY5Y: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P=0.006; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P=0.001. HT-29: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, NS; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P=0.005. (d) Western blot analysis of Bid expression was quantified by densitometry analysis and values were expressed as OD-Bkg/mm2 × 103. Histograms represent mean values±S.D. from the three independent experiments performed on each cell line. Statistical comparison of means using the the Bonferroni's post-hoc multiple comparison ANOVA test, provided the following results. MOLT-3: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P=0.008; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P <0.001. SH-SY5Y: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, P=0.016; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P <0.001. HT-29: control 3 h versus control 18 h, NS; treated 3 h versus control 3 h, NS; and treated 18 h versus control 18 h, P=0.005

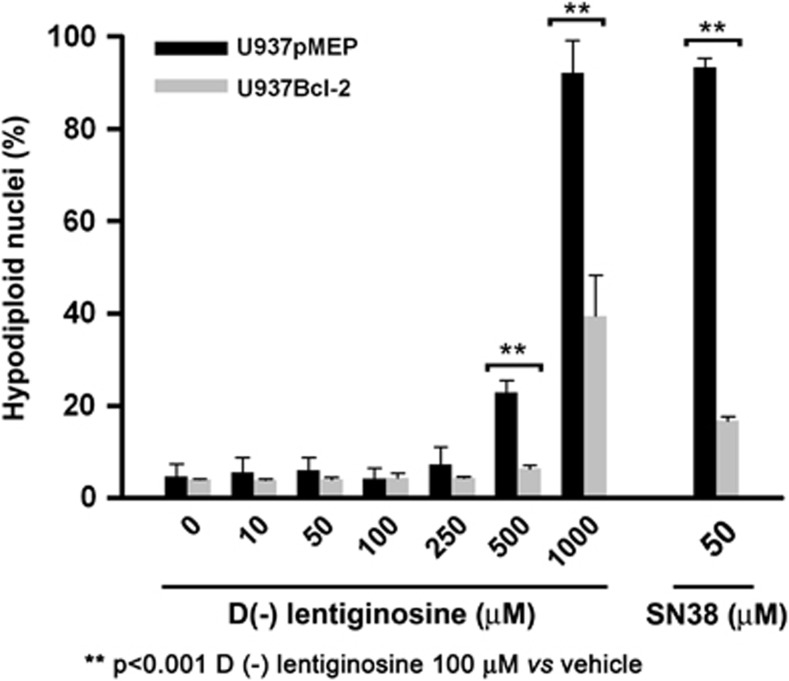

Effects on Bcl-2 overexpressing and p53-deficient cells

We considered that the tested cell lines exhibited, in normal conditions, a relatively low constitutive expression of Bcl-2 to properly define whether downregulation of this protein was indispensable to drive 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-treated cells towards apoptosis. Thus, to assess the role of Bcl-2 in 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced apoptosis, we took advantage of an experimental model available in our laboratory, that is, U937-transfectant cells overexpressing murine Bcl-2 (U937Bcl-2). Both the U937Bcl-2 and the U937pMEP control cells were treated with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine at different concentrations for 18 h. The results in Figure 6 refer to the cumulative mean values of three experiments performed and show that U937Bcl-2 were highly resistant to undergoing apoptosis even after treatment with high concentrations of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. As a control, the same experiments showed that U937Bcl-2 cells were also resistant to apoptosis induced by etoposide, a well-known intrinsic-pathway-related pro-apoptotic inducer.

Figure 6.

Susceptibility to apoptosis of U937Bcl-2 and U937pMEP cells. Both transfectants were treated with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine at the concentration of 10, 50, 100, 250, 500 and 1000 μM for 18 h. The data on Y-axis are expressed as percentage hypodiploid nuclei, as detected by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry analysis. As a positive control, etoposide at the concentration of 50 μM was used. Data are presented as mean values±S.D. from three experiments performed in duplicate (n=6). Asterisks (**) indicate highly significant differences between treated and untreated cells (P <0.001)

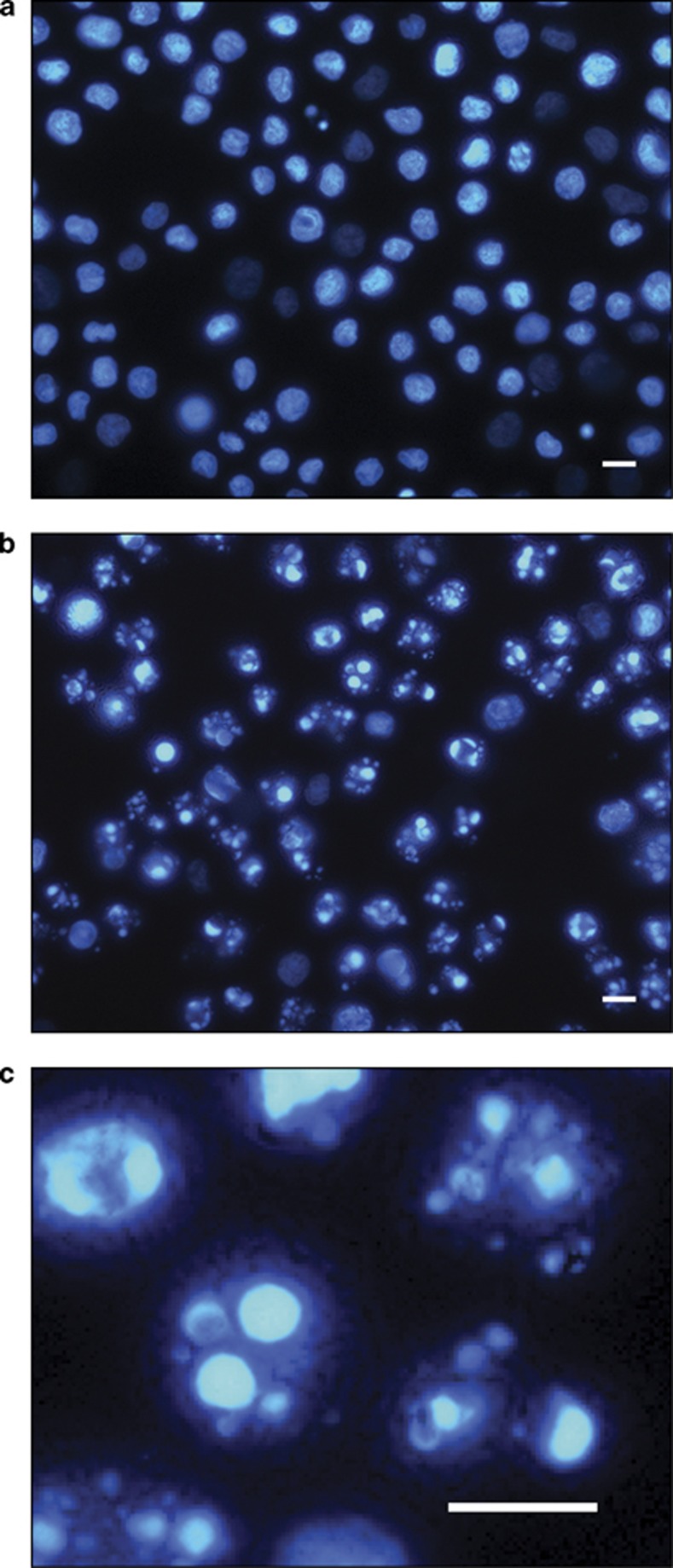

Moreover, it is known that loss of p53 function and related apoptotic responses to a number of anti-tumour agents frequently occur in human cancers.22 We then asked whether 𝒟(−)lentiginosine maintained its pro-apoptotic activity not only in HT-29 cells, known to lack functional p53, but also in other p53-deficient cells. To this purpose, we utilized U937 cells for which the inability to efficiently express p53 and consequently initiate a p53-mediated apoptotic response is well reported.23 Results shown in Figure 7 incontrovertibly demonstrate that after exposure for 18 h to 500 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, the higher concentration assayed in this series of experiments, most of the U937 cells acquired the typical morphology of apoptotic cells, indicating a clear p53 independency for 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced apoptosis.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence microscopy analysis of U937 cells treated with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. Control cells (a) and cells treated with 500 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine (b and c) were analysed at 18 h incubation after staining with the fluorescent DNA-binding dye Hoechst. In treated samples (b and c), many cells show typical characteristics of advanced apoptosis with nuclei present as one or, more frequently, more groups of featureless, bright, spherical beads. (c) Detail of b. Original magnification ( × 630). Scale bar=10 μm

Discussion

Previous data obtained in our laboratories had disclosed for the first time an unknown activity of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine: its capacity to induce cell death in both lymphoid and epithelial cells through caspase activation.16 Particularly, both caspase 8 and 3, the only caspases assayed in our previous study, were found to be induced and activated in cells treated with this non-natural compound. However, based on results of that study it was not possible to elucidate which apoptotic pathway was preferentially routed by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. In the present study, we sought to better characterize the signalling pathways underlying caspase activation and consequent cell death induced by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. Preliminary assays performed to assess the effect of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine on the extrinsic apoptotic pathway revealed that neither Fas expression was modulated in cells treated with this compound nor treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine was able to co-stimulate or interfere with Fas-induced cell death (data not shown). Then, we directed our interest in investigating whether the pro-apoptotic effect of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine was involved in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. As a first result of the present study, we clearly show that 𝒟(−)lentiginosine was actually able to invariably increase the expression of caspase 9 in cells of different origin. It is well known that the activation of caspase 9 is preceded by a number of signalling events within the mitochondrial platform. Actually, an array of death stress, including chemotherapeutic agents, induce permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) followed by release of apoptotic proteins into the cytosol. The data we obtained undoubtedly show that 𝒟(−)lentiginosine caused failure of the mitochondria membrane potential and release of cytochrome c, two main events that drive the progression of the signalling pathway, leading to the release of activated caspase 9. It is also known that members of the Bcl-2 family have a key role in determining cell death through mitochondria. Our results of real-time PCR analysis suggest that 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced apoptosis is presumably owed both to downregulation of anti-apoptotic genes of the Bcl-2 family and to a concomitant upregulation of pro-apoptotic genes of the same family. The comparison among the various anti- and pro-apoptotic gene expressions showed that BCL-2 transcription was highly downregulated following treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. Also BCL-XL gene expression was downregulated in comparison with control samples, in all the tested cell lines. Conversely, the pro-apoptotic BAX, BIM and BID genes were all upregulated in cells treated with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. In fact, it can be hypothesized that the high increase of BID expression in 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-treated cells could be a downstream signalling induced by caspase 8 that was shown to be activated by this compound in our previous study.16 Actually, caspase 8 has been shown to have a major role in the cleavage of the Bcl-2 family member Bid.24 Following Bid activation, a truncated tBid is generated, which is able to induce OMM permeabilization, leading to progression towards cell death. Generation of tBid is fundamental for binding Bax, which insert into the mitochondrial membrane bilayer and determine apoptotic cell death. Thus, it can be hypothesized that both Bid and Bax might have a role in 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced progression of the apoptotic cascade. Nevertheless, our results show that the turnover of BAX and BID mRNA expression in treated and control cells, respectively, as detected by real-time PCR, was different. Indeed, levels of BAX transcripts were very high in assayed cells after various times of treatment, but the difference between treated and control samples was not significant. Conversely, BID, which was expressed at low level in control cells, showed a significant increase in treated cells. However, the difference in significance of upregulation between the two genes might be due to their different constitutive expression. Moreover, protein expression and functional activation of Bax should not be necessarily mirrored by an increased expression of its mRNA. In fact, analysis at the protein level clearly showed that both Bax and Bid proteins were upregulated in cells treated with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine with respect to control cells, strongly enforcing a role for these proteins as upstream signals of caspase activation and apoptosis as driven by this compound. We have not considered in this study other pro-apoptotic members of the BH3-only family, such as PUMA and NOXA, that could also be involved in triggering apoptosis induced by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. In addition to BAX and BID, other pro-apoptotic genes were shown to be upregulated in association with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced cell death, such as APAF-1 and BIM, further confirming the possible involvement of the apoptotic intrinsic pathway in 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced cell death. Finally, evidence that both HT-29 and U937 cells, which are p53 deficient, are susceptible to 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced apoptosis should exclude the idea that the p53 tumour suppressor could be essential in 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-mediated cell death. Taken together, the data reported in the present study indicate that 𝒟(−)lentiginosine activates the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. However, based on our results, it is still unclear whether upstream signals such as metabolic or stress signals, including p53, where active or other members of its family, such as p73 pro-apoptotic forms, which can target BH3 independently of p53 (Rufini et al.25),could cooperate in triggering the supposed pathway during 𝒟(−)lentiginosine-induced cell death. Moreover, it cannot be excluded that also the extrinsic pathway, through signalling different from that of Fas, could contribute to caspase activation and cell death driven by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. In addition, our results do not elucidate whether a possible glycosidase-inhibitory activity of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine might have a role in tipping the balance towards apoptosis in treated cells. However, neither data reported in the present study nor our previous results allow any conclusion, supporting an involvement of glycosidase inhibition in the process of apoptosis driven by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine. Moreover, we must also consider that no glycosidase-inhibitory activity other than that exerted on the fungal amyloglucosidase has been found at the moment for both the enantiomers of lentiginosine.26 Accordingly, it seems plausible that the alterations of MMP or OMM, which we found after treatment with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, might be routed through a signalling process different from glycosidase inhibition. However, because various glycosidase inhibitors have been proven to exhibit a number of different effects on carbohydrate cell biology, and given the fundamental role for carbohydrate processing in cell proliferation and survival, we can hypothesize that an unknown step in carbohydrate cell metabolism could be the initial target for induction of apoptosis by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine through the intrinsic pathway. Results reported in this study led to a better characterization of the phenomenon of apoptosis induced by 𝒟(−)lentiginosine, further enforcing its functional classification as a cytotoxic, pro-apoptotic agent. Because synthetic compounds, derived from natural prototype structures, have been considered as potentially useful for the development of molecules of therapeutic interest, the results of this study encourage further investigation into the role of the lentiginosine family of compounds in interfering with the signalling and growth of cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

𝒟(−)lentiginosine was synthesized according to the reported procedure 27 recently improved15 and dissolved in RPMI 1640 culture medium without supplements.

Cell cultures

The human acute T lymphoblastic MOLT-3, U937 cell lines (Zooprofilactic Institute, Brescia, Italy) and the human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cell line (American type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) were grown in suspension and adhesion culture, respectively, at a density of 2 × 105 cells per ml. These cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies), 2 mM glutamine (Hyclone, Cramlington, UK), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 U/ml streptomycin (Hyclone). The human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line (Zooprofilactic Institute) was routinely grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). U937 human monocytoid cells expressing the pMEP control vector (U937pMEP) or the vector containing the murine Bcl-2 (U937Bcl-2) have been previously described.28 They were maintained in the same conditions as MOLT-3 and HT-29 cells, except for the addition of hygromycin B (50 μg/ml). Preliminary assays showed that these culture conditions were sufficient to warrant phenotypical and functional overexpression of the ectopic gene. Cells utilized in all experiments were derived from aliquots expanded at the initial passages, kept as a frozen stock and used immediately after thawing and readapting to growth in culture. All the cell lines were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Apoptosis assays

For induction of apoptosis, cells were grown in the presence or absence of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine at different concentrations for different times. Apoptosis was assessed through flow cytometry analysis of isolated nuclei stained with propidium iodide, carried out on a Becton Dickinson FACS analyser, or by morphological analysis following staining with Hoechst chromatin dye, as previously described by some of us.29, 30

JC-1 assay

For assaying the MMP, MOLT-3, HT-29 and SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 𝒟(−)lentiginosine at concentrations of 50, 100 and 250 μM for 18 h. The assay was performed using the MitoProbe JC-1 assay kit for flow cytometry (Molecular Probes Europe BV, Leiden, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The MitoProbe JC-1 assay kit supplies the cationic dye, JC-1, and a MMP disrupter, carbonyl cyanide 3-lorophenylhydrazone, as a positive control, for the study of MMP. JC-1 exhibits potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria, indicated by a fluorescence emission shift from green (∼529 nm) to red (∼590 nm). Consequently, mitochondrial depolarization is indicated by a decrease in the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio. Cells were analysed on a flow cytometer using 488 and 633 nm excitations.

Quantitative detection of cytochrome c

Quantification of human cytochrome c was performed through an ELISA. Cells were cultured for different times (3 and 18 h ) with 100 μM of 𝒟(−)lentiginosine or control diluent. Then, the cell extract was processed according to the manufacturer's protocol (human cytochrome c ELISA; BioVendor GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). The absorbance was determined at 450 nm with wavelength correction at 650 nm using a Labsystem Multiskan Bichromatic spectrophotometer (Helsinki, Finland).

Western blot analysis

For western blot analysis, a total number of 5 × 106 cells from all cell lines, treated with 0 or 100 μM 𝒟(−)lentiginosine for 3 h and 18 h, were solubilized at 4 °C in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA pH 7.4, 1% Triton-X, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40 and, freshly added, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μM DTT, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 20 mM Na3F; all from Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and centrifuged at 10 000 × g for 20 min. The amount of protein obtained from 5 × 105 cells was loaded onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). After blocking the membrane in 10% non-fat dried milk and 3% BSA in TTBS (20 mM TRIS-HCL pH 8.0, 0.9% NaCl and 0.03% Tween 20; all from Sigma), the blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C with diluted primary antibody and, subsequently, washed and then incubated with anti-mouse (Bio-Rad laboratories) or anti-rabbit IgG chain-specific conjugated to peroxidase (Calbiochem, Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany). Binding of antibodies was detected by chemoluminescence staining using the ECL detection kit (Amersham Bioscences). The following primary antibodies where used: mouse anti-human caspase-9 (1 : 5000; BD Bioscence Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), mouse anti-human Bax (1 : 3000; Abcam, Cambridge UK), rabbit anti-human Bid (1 : 3000) and mouse anti-human beta-actin (1 : 8000; Novus Biologicals LLC, Littleton, CO, USA). Comparative, quantitative evaluation of the immunoblot results was performed by densitometry analysis using the Tina software (version 2.10; Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany). The densitometry values for each sample were normalized to their respective β-actin values.

RQ-PCR

Real-time PCR was performed on a CFX-96 Real-time system (Bio-Rad laboratories) with gene-specific primers using sybr green detection. All the primers employed were cDNA-specific and were purchased from Primm (Milan, Italy). The names and primer sequences for all genes investigated in the text are listed in Table 1. An amount of 0.25 μg of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed in a total volume of 20 μl with high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1. Primer pairs used in quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis.

| Gene bank number | Forward | Reverse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl-2 | NM_000633 | 5′-TCCCTCGCTGCACAAATACTC-3′ | 5′-ACGACCCGATGGCCATAGA-3′ |

| Bcl-xL | NM_138578 | 5′-GGAGTCAGTTTAGTGATGTGGAAGAG-3′ | 5′-CATCTCCGATTCAGTCCCTTCT-3′ |

| Bax | NM_004324 | 5′-CCAAGGTGCCGGAACTGA-3′ | 5′-CCCGGAGGAAGTCCAATGT-3′ |

| Apaf-1 | NM_001160 | 5′-TGGAATGGCAGGCTGTGGGA-3′ | 5′-TGCACTCCCCCTGGGAAACA-3′ |

| Bim | NM_006538 | 5′-AGAGCCACAAGACAGGAGCCCA-3′ | 5′-CAGCCTGCCTCATGGAAGCCA-3′ |

| Bid | NM_001196 | 5′-AGCGGGTAGTCGACCGTGTCCG-3′ | 5′-AGACCCGGCCCTCAGGTCGC-3′ |

| GUSB | NM_000181 | 5′-CAGTTCCCTCCAGCTTCAATG-3′ | 5′-ACCCAGCCGACAAAATGC-3′ |

Amplification of specific PCR products was detected using the SYBR Green PCR Real Master Mix (Bio-Rad laboratories). The RQ-PCR was performed in duplicate in a total reaction volume of 25 μl containing 11.25 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 150 nM forward and reverse primers, 10.25 μl dH2O and 750 ng cDNA as a template. Samples were heated for 10 min at 95 °C and were subjected to 45 cycles of PCR amplification, each cycle consisting of 15 s at 95 °C and 60s at 60 °C. Within each experiment, a no-template control and the housekeeping gene β-actin (ACTB) were run in parallel to verify any contamination and determine amplification efficiency. Each run was completed with a melting curve analysis to confirm the specificity of amplification and lack of unspecific products and primer dimers. Quantification was performed using the Ct comparative method. The relative gene mRNA levels were calculated as follows: ΔCt values (Ct(gene of interest)−Ct(internal control housekeeping gene GUSB)) represents the difference, in threshold cycle number, between genes of interest and the housekeeping gene GUSB. To compare the expression of different genes, ΔCt values were normalized to the mean value of ΔCt from the least expressed gene (2−− ΔΔCt= 2− (ΔCt (gene of interest)−mean value of the less expressed gene ΔCt (normalizer))). The obtained relative 2−ΔΔCtvalues of the genes of interest were then compared to evaluate the drug effect.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in duplicate or triplicate. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. Statistical analysis of data was performed using the SPSS statistical software system (version 12.0 for Windows, Chicago, IL, USA). Comparison of means in response to 𝒟(−)lentiginosine treatment were carried out, in all cases, using the Bonferroni's post-hoc multiple comparison analysis of variance test.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Research, Projects of National Interest (PRIN to AB and BM); Istituto Superiore di Sanità, AIDS Project; the University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata' (BM); and the University of Messina (AM).

Glossary

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- OMM

outer mitochondrial membrane

- U937pMEP

U937 human monocytoid cells expressing the pMEP control vector

- U937Bcl-2

vector containing the murine Bcl-2

- JC-1

5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide

- RQ-PCR

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by G Raschellá

References

- Cipolla L, La Ferla B, Gregori M. Combinatorial approaches to iminosugars as glycosidase and glycosyltransferase inhibitors. Comb Chem High T Scr. 2006;9:571–582. doi: 10.2174/138620706778249703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier MF, Marcil A, Sevigny G, Jakob CA, Tessier DC, Chevet E, et al. The heterodimeric structure of glucosidase II is required for its activity, solubility, and localization in vivo. Glycobiology. 2000;10:815–827. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.8.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CS, Wang H, Li GX, Yang Z, Guan F, Jin H. Cancer prevention by tea: evidence from laboratory studies. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magyar JE, Gamberucci A, Konta L, Margittai E, Mandl J, Banhegyi G, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress underlying the pro-apoptotic effect of epigallocatechin gallate in mouse hepatoma cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamberucci A, Konta L, Colucci A, Giunti R, Magyar JE, Mandl J, et al. Green tea flavonols inhibit glucosidase II. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash RJ, Kato A, Yu CY, Fleet GW. Iminosugars as therapeutic agents: recent advances and promising trends. Future Med Chem. 2011;3:1513–1521. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padro M, Castillo JA, Gomez L, Joglar J, Clapes P, de Bolos C. Cytotoxicity and enzymatic activity inhibition in cell lines treated with novel iminosugar derivatives. Glycoconj J. 2010;27:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s10719-009-9276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox T, Lachmann R, Hollak C, Aerts J, van Weely S, Hrebicek M, et al. Novel oral treatment of Gaucher's disease with N-butyldeoxynojirimycin (OGT 918) to decrease substrate biosynthesis. Lancet. 2000;355:1481–1485. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrakou A, Tountas N, Raptis AE, Bauer RJ, Schulz H, Raptis SA. Long-term effectiveness of a new alpha-glucosidase inhibitor (BAY m1099-miglitol) in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1998;15:657–660. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199808)15:8<657::AID-DIA652>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrodnigg TM, Steiner AJ, Ueberbacher BJ. Natural and synthetic iminosugars as carbohydrate processing enzyme inhibitors for cancer therapy. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:77–85. doi: 10.2174/187152008783330851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y. gem-Diamine 1-N-iminosugars and related iminosugars, candidate of therapeutic agents for tumor metastasis. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:575–591. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pili R, Chang J, Partis RA, Mueller RA, Chrest FJ, Passaniti A. The alpha-glucosidase I inhibitor castanospermine alters endothelial cell glycosylation, prevents angiogenesis, and inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2920–2926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Fernandez EM, Risquez-Cuadro R, Chasseraud M, Ahidouch A, Ortiz Mellet C, Ouadid-Ahidouch H, et al. Synthesis of N-, S-, and C-glycoside castanospermine analogues with selective neutral alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity as antitumour agents. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:5328–5330. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00446d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona F, Goti A, Brandi A. (+)-Lentiginosine, a potent and selective inhibitor of amyloglucosidase: Synthetic efforts and disputes on its absolute configuration. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;10:1551–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero MF, Bonanno P, Khairnar BB, Cardona F, Brandi A, Macchi B, et al. (−)-(1R,2R,7S,8aR)-1,2,7-Trihydroxyindolizidine ((−)-7S-OH-Lentiginosine): synthesis and proapoptotic activity. ChemPlusChem. 2012;77:9. [Google Scholar]

- Macchi B, Minutolo A, Grelli S, Cardona F, Cordero FM, Mastino A, et al. The novel proapoptotic activity of nonnatural enantiomer of lentiginosine. Glycobiology. 2010;20:500–506. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, Cory S, Adams JM. Deciphering the rules of programmed cell death to improve therapy of cancer and other diseases. EMBO J. 2011;30:3667–3683. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S, Low ICC, Pervaiz S. Regulation of mitochondrial metabolism: yet another facet in the biology of the oncoprotein Bcl-2. Biochem J. 2011;435:545–551. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamas-Din A, Brahmbhatt H, Leber B, Andrews DW. BH3-only proteins: orchestrators of apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ola MS, Nawaz M, Ahsan H. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;351:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0709-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Induction of apoptosis by cancer chemotherapy. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:42–49. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller PA, Vousden KH, Norman JC. p53 and its mutants in tumor cell migration and invasion. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:209–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durland-Busbice S, Reisman D. Lack of p53 expression in human myeloid leukemias is not due to mutations in transcriptional regulatory regions of the gene. Leukemia. 2002;16:2165–2167. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantari C, Walczak H. Caspase-8 and bid: caught in the act between death receptors and mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufini A, Agostini M, Grespi F, Tomasini R, Sayan BS, Niklison-Chirou MV, et al. p73 in Cancer. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:491–502. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi A, Cicchi S, Cordero FM, Frignoli R, Goti A, Picasso S, et al. Assignment of the absolute-configuration of natural lentiginosine by synthesis and enzymatic assays of optically pure (+)-enantiomers and (−)-enantiomers. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6806–6812. [Google Scholar]

- Goti A, Cardona F, Brandi A. Improved syntheses of (+)-lentiginosine and (1S,2S,7R,8aS)-trihydroxyoctahydroindolizine by butenol cycloaddition to enantiopure protected dihydroxy pyrroline N-oxides. Synlett. 1996;8:761. [Google Scholar]

- Borner C. Diminished cell proliferation associated with the death-protective activity of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12695–12698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastino A, Sciortino MT, Medici MA, Perri D, Ammendolia MG, Grelli S, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 causes apoptotic infection in monocytoid cells. Cell Death Differ. 1997;4:629–638. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci C, Minutolo A, Balestrieri E, Ascolani A, Grelli S, Macchi B, et al. Effector caspase activation, in the absence of a conspicuous apoptosis induction, in mononuclear cells treated with azidothymidine. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]