Background: Silver ions block ethylene perception yet support ethylene binding to Ethylene Receptor 1 (ETR1).

Results: Loss of ETR1 reduces the effects of silver while loss of the other receptors has less of an effect.

Conclusion: ETR1 has the predominant role and is sufficient for the effects of silver.

Significance: This could underlie differences in the roles of the receptors in plants.

Keywords: Copper, Plant, Plant Biochemistry, Plant Hormones, Plant Molecular Biology, Receptors, Signal Transduction, Ethylene, Silver

Abstract

Ethylene influences many processes in Arabidopsis thaliana through the action of five receptor isoforms. All five isoforms use copper as a cofactor for binding ethylene. Previous research showed that silver can substitute for copper as a cofactor for ethylene binding activity in the ETR1 ethylene receptor yet also inhibit ethylene responses in plants. End-point and rapid kinetic analyses of dark-grown seedling growth revealed that the effects of silver are mostly dependent upon ETR1, and ETR1 alone is sufficient for the effects of silver. Ethylene responses in etr1-6 etr2-3 ein4-4 triple mutants were not blocked by silver. Transformation of these triple mutants with cDNA for each receptor isoform under the promoter control of ETR1 revealed that the cETR1 transgene completely rescued responses to silver while the cETR2 transgene failed to rescue these responses. The other three isoforms partially rescued responses to silver. Ethylene binding assays on the binding domains of the five receptor isoforms expressed in yeast showed that silver supports ethylene binding to ETR1 and ERS1 but not the other isoforms. Thus, silver may have an effect on ethylene signaling outside of the ethylene binding pocket of the receptors. Ethylene binding to ETR1 with silver was ∼30% of binding with copper. However, alterations in the Kd for ethylene binding to ETR1 and the half-time of ethylene dissociation from ETR1 do not underlie this lower binding. Thus, it is likely that the lower ethylene binding activity of ETR1 with silver is due to fewer ethylene binding sites generated with silver versus copper.

Introduction

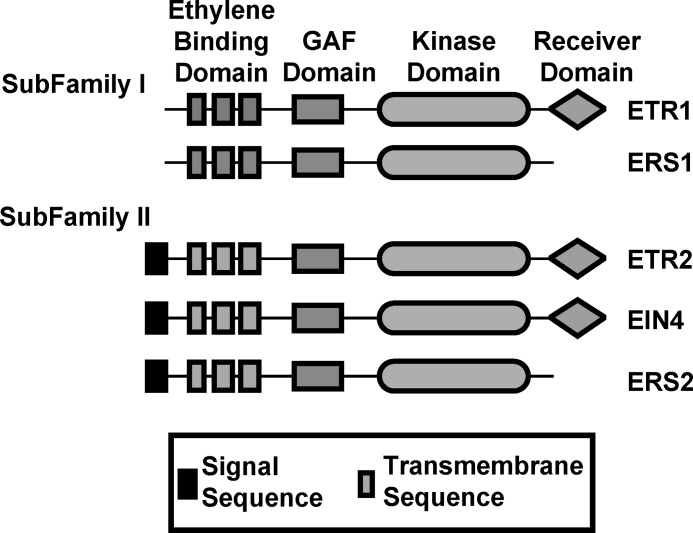

Ethylene is a gaseous plant hormone that influences a number of processes in higher plants such as seed germination, abscission, senescence, fruit ripening, response to stress, and growth. In etiolated Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings, ethylene causes a number of changes including reduced growth of the hypocotyl and root, increased radial expansion of the hypocotyl, increased tightening of the apical hook, and an increase in root hair formation (1). Responses to ethylene are mediated by a family of five receptors in Arabidopsis (2–5). Based upon domain structure and sequence comparisons of the ethylene binding domain, the ethylene receptors in Arabidopsis can be divided into two subfamilies (Fig. 1) (6). Subfamily I consists of ETR12 (ethylene receptor 1) and ERS1 (ethylene response sensor 1) and subfamily II includes ETR2, ERS2, and EIN4 (ethylene insensitive 4) (2–5).

FIGURE 1.

Domains of the ethylene receptors from Arabidopsis. All of the receptor isoforms contain ethylene binding, GAF and kinase domains. A subset of the receptors contain a receiver domain and subfamily II receptors have an extra N-terminal sequence as shown.

All five receptor isoforms are involved in ethylene signaling and have overlapping roles that regulate various phenotypes such as growth (2, 4, 6–8). However, it is also clear that the five receptor isoforms in Arabidopsis are not entirely redundant in their roles (9–21). This appears to be a general feature of ethylene signaling since only specific receptor isoforms mediate fruit ripening in tomato (22). The basis for these non-overlapping roles is unclear but may involve structural or functional differences. The ethylene receptors are homologous to two-component receptors and have three membrane-spanning α-helices at the N-terminal region containing the ethylene-binding domain followed by a GAF domain and a domain with similarities to bacterial histidine kinases (Fig. 1). The subfamily II receptors have an extra hydrophobic region at the N terminus that might function as a signal sequence. Two-component receptors transduce signals via His autophosphorylation followed by the transfer of that phosphate to an Asp residue in the receiver domain (23). However, not all the ethylene receptor isoforms have His kinase activity (24, 25). Additionally, only three of the five receptor isoforms (ETR1, ETR2, EIN4) contain a receiver domain at the C terminus (Fig. 1). Alternatively, the non-overlapping roles of the receptors may be due to other proteins that modulate specific receptor isoforms. For instance, RTE1 (reversion to ethylene sensitivity 1) is a protein that has recently been shown to specifically interact with and affect ETR1 (26–29). This modulation may occur through interactions with the ETR1 ethylene binding domain (30, 31).

It has been shown that copper is required for high-affinity ethylene binding in exogenously expressed ETR1 receptors (32) supporting earlier speculations about the requirement for a transition metal cofactor for ethylene binding (33–36). This requirement for copper is likely to be a general feature of all ethylene receptors in plants (15). Additionally, prior studies indicate that RAN1 (response to antagonist 1) is a copper transporter that acts upstream of the receptors and is required for normal biogenesis of the receptors (37–40). Interestingly, the etr1-1 mutant protein fails to coordinate copper and is unable to bind ethylene (32, 41). Together, these studies have led to a model where copper ions are delivered to and required by the ethylene receptors for ethylene binding. It is thought that ethylene binding causes a change in the coordination chemistry of the copper cofactor resulting in a change in the binding site that is transmitted through the receptor to downstream signaling elements (42).

Of many other transition metals previously tested, only the two other Group 11 transition metals (silver and gold ions) supported the binding of ethylene to ETR1 (32, 43). This observation is of interest since silver has long been recognized for its ability to block ethylene responses in plants (34). Since Ag+ is larger than Cu+, a model has been developed proposing that silver occupies the binding site and interacts with ethylene but prevents stimulus response coupling through the receptors because of steric effects (19, 32, 43, 44). However, there is some evidence indicating that the action of silver on ethylene responses in Arabidopsis is not so clear-cut and may only involve the subfamily I receptors (12, 45). If true, this suggests that the ethylene-binding domains of the subfamily I and II receptors are different from each other. In the current study we examined the ability of silver to block ethylene responses in a variety of receptor-null plants using both end-point and growth kinetic analyses. This information was compared with the ability of silver to act as a cofactor for ethylene binding to exogenously expressed ethylene receptors. We also further characterized the effects of silver on the ETR1 receptor. Results presented in the current study support more complex models for the effects of silver on ethylene receptor function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

The etr1-6, etr1-7, etr2-3, ers2-3, and ein4-4 mutants were originally obtained from Elliot Meyerowitz (3), the ers1-3 and etr1-9 mutants were from Eric Schaller (11), the ers1-3;etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2–3 quadruple mutants were obtained from Chi-Kuang Wen (9, 20), and the rte1-2 mutants were from Caren Chang (26). The etr1-6, etr1-7, and etr1-9 loss-of-function mutants have previously been shown to be similar since they result in similar alterations in phenotypes (3, 11). Other combinatorial mutants used in this study have previously been described (10, 11, 46). All mutants are in the Columbia (Col) background except for etr1-9, ers1-3, and ers1-2 that are in the Wassileweskija (Ws) background. All transgene constructs and transgenic plant lines have been described previously (13, 16, 20, 46). 14C2H4 was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO).

Seed Preparation, Growth Measurements, and Imaging

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds were surface sterilized and germinated as previously described (16, 43, 47). For silver treatment, 100 μm silver nitrate was included in the agar. End-point analysis growth experiments using 10 seeds per condition were carried out as previously described (43) except that 100 μl/liter ethylene was used, and the gas flow rate was maintained at 50 ml min−1. Growth kinetic experiments were carried out, analyzed, and normalized to the growth rate in air prior to ethylene treatment as previously described (16, 47–49). All growth experiments were carried out in the dark. Infrared light emitting diodes were used for imaging during growth kinetic experiments. Images of unfixed seedlings grown and treated as described above were acquired using a CanoScan 4400F flat-bed digital scanner (Canon, Lake Success, New York).

Ethylene Concentration Measurements

Ethylene concentrations were determined using a Hewlett-Packard 6890 gas chromatograph with an HP Plot/Q column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) or an ETD-300 photoacoustic laser spectrophotometer (Sensor Sense, The Netherlands).

DNA Constructs, Cell Strains, Growth Conditions, and Membrane Isolation

Pichia pastoris (Invitrogen) was used to express the binding domain of each receptor fused to GST (glutathione S-transferase). We used the following nomenclature for these constructs: ETR1[1–128]-GST, ETR2[1–157]-GST, ERS1[1–128]-GST, ERS2[1–160]-GST, EIN4[1–151]-GST for the binding domains of ETR1, ETR2, ERS1, ERS2, and EIN4 respectively fused to GST (15). These constructs were described and characterized previously using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as the expression system (15, 32).

To generate these constructs for use in P. pastoris, the sequence encoding the ethylene binding domain of each receptor was amplified by PCR using cDNA generated from Col seedlings. The GST sequence was PCR amplified using the pGEX vector. The receptor-specific primers introduced the EcoRI restriction site at the N terminus and KpnI at the C terminus and the GST-specific primers introduced KpnI at the N terminus and ApaI at the C terminus. The ETR1[1–128] construct was generated by PCR amplification using the forward primer 5′-AATTCATAGCCACCATGGAAGTCTGCAAT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-ATATAGGTACCCTCAGCAGCTTTATTTTTCA-3′, ERS1[1–128] using the forward primer 5′-AATTCATAGCCACCATGGAGTCATGCGAT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTAATGGTACCCTCATCAGCTTTCTTC-3′, ETR2[1–157] using the forward primer 5′-AATTCATAGCCACCATGGTTAAAGAAATAGCT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-ACGATAGGTACCCTCATGAGCTTTCTT-3′, ERS2[1–160] using the forward primer 5′-AATTCATAGCCACCATGTTAAAGACATTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTAATGGTACCCTCTCTGGTCTTCTTAC-3′, and EIN4[1–151] using the forward primer 5′-AATTCATAGCCACCATGTTAAGATCTTTA-3′, and the reverse primer 5′-ATATAGGTACCCTCCAACACATTCTG-3′. The GST sequence was amplified using the forward primer 5′-ATAGGTACCATGTCCCCTATACTAGGT-3′, and the reverse primer 5′-ATAATTGGGCCCTTATCAGTCACGATGCG-3′. Following PCR amplification, each fragment was gel purified, digested using EcoRI and KpnI, ligated into the pPICZ A vector, and subsequently transformed into Escherichia coli. Plasmids were isolated from positive colonies, and receptor and GST gene fragments were digested with KpnI and ApaI and ligated together. Plasmids containing the complete receptor-GST construct were sequenced to confirm no errors were present, then linearized, and transformed into P. pastoris using electroporation. Yeast cultures expressing each construct were grown under conditions described in the Invitrogen Pichia manual for membrane-bound proteins. Following a 48 h induction, the yeast cells were isolated and membranes purified using previously described methods (50). Membranes were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until used.

Ethylene Binding Assays

Prior to assaying ethylene binding activity, 300 μm of either silver nitrate or CuSO4 was added to the assay buffer. In some cases, neither metal salt was added. Saturable ethylene binding to membranes isolated from yeast expressing the binding domain of each receptor isoform fused to GST was determined using the methods of Sisler (51) as modified by others (32, 50). In some cases empty vector controls were included. The time-course of ethylene dissociation from ETR1[1–128]-GST and the Kd for ethylene binding to ETR1[1–128]-GST were determined according to methods from prior studies (15, 41, 52).

RESULTS

Receptor Requirements for the Ethylene Blocking Effects of Silver Nitrate

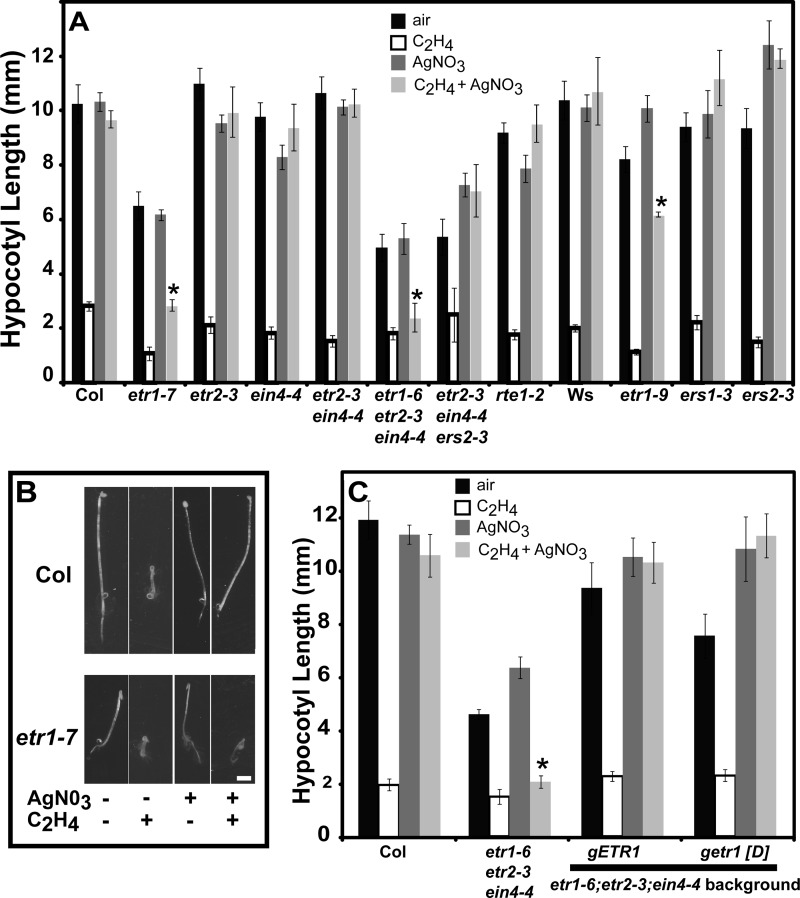

Previous observations that Arabidopsis plants lacking subfamily II receptors still respond to silver while those lacking subfamily I receptors do not implies that silver acts through the subfamily I receptors (12, 45). To more completely characterize this phenomenon, we conducted a more thorough evaluation of the effects of silver on various single and combinatorial receptor loss-of-function mutant seedlings. We initially examined the effects of 100 μm silver nitrate on seedlings grown for 4 days in the dark in air or treated with 100 μl/liter ethylene (Fig. 2). We observed that like their respective wild-type controls, silver nitrate blocked growth inhibition upon application of ethylene in most single receptor loss-of-function seedlings including etr2-3 and ein4-4 in the Col background and ers1-3 and ers2-3 mutants in the Ws background. Similarly, silver nitrate blocked ethylene responses in etr2-3;ein4-4 double mutants and etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2-3 triple mutants (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of silver nitrateon ethylene growth responses of dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. In all panels, seedlings were grown in darkness for 4 days under the indicated conditions. A concentration of 100 μl/liter ethylene and 100 μm silver nitrate was used. Data represent the mean hypocotyl length ± S.E. Differences between air and ethylene in the presence of silver were analyzed with t tests and considered statistically significant with p < 0.001 (*). A, hypocotyl growth of ethylene receptor loss-of-function and rte1 mutant seedlings were examined. Wild-type seedlings were included as controls. The etr1-7, etr2-3, ein4-4, etr2-3;ein4-4, etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4, and etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2-3, and rte1-2 mutants are in the Col background while etr1-9, ers1-3, and ers2-3 are in the Ws background. B, Col and etr1-7 seedlings treated with air or ethylene in the presence or absence of silver as labeled. Scale bar equals 2 mm. C, growth of etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutants transformed with a wild-type genomic ETR1 (gETR1) transgene or a mutant transgene that lacks the conserved aspartate in the receiver domain for phosphotransfer (getr1 [D]). Col, Columbia; Ws, Wassilewskija.

In marked contrast to these observations, etr1-7 and etr1-9 mutants had a measurably reduced response to silver nitrate(Fig. 2, A and B). In other words, silver nitrate only partially blocked growth inhibition upon application of ethylene. Interestingly, this is similar to what we have previously observed in the ran1-1 and ran1-2 partial loss-of-function mutants (39). Of the combinatorial receptor loss-of-function mutants examined, only the etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutant seedlings had an altered response to silver nitrate (Fig. 2, A and C). In these mutants, silver nitrate had no measurable effect on the magnitude of growth inhibition caused by ethylene. Thus, mutants containing an etr1 loss-of-function mutation are less responsive to the ethylene response blocking effects of silver.

These results point to a key role for ETR1 in mediating the effects of silver. To confirm this failure to respond to silver is due to ETR1, we transformed etr1–6;etr2–3;ein4–4 triple mutants with a genomic ETR1 transgene (gETR1). Consistent with prior research (16, 20), the gETR1 transgene rescued the reduced growth phenotype of the triple mutant (Fig. 2C). This transgene also rescued the silver phenotype so that silver nitrate once again blocked ethylene's effects in these transformants (Fig. 2C). One distinguishing characteristic of ETR1 is that it has both His kinase activity and a receiver domain with a conserved aspartate for phosphotransfer (24, 25). Therefore, we transformed this triple mutant with a genomic ETR1 transgene lacking the conserved aspartate required for phosphotransfer (getr1[D]) to determine if this was required for the silver phenotype. The getr1[D] transgene rescued the silver phenotype as well as the gETR1 transgene (Fig. 2C) indicating that phosphotransfer through ETR1 is not required. Another distinguishing characteristic of ETR1 is that it is specifically modulated by RTE1 (26–31). However, the ethylene growth inhibition response in rte1-2 mutants was blocked by silver nitrate (Fig. 2A). Thus, the effects of silver on plants do not require phosphotransfer through ETR1 or a functional RTE1.

The Effects of Silver Nitrate on Ethylene Growth Response Kinetics

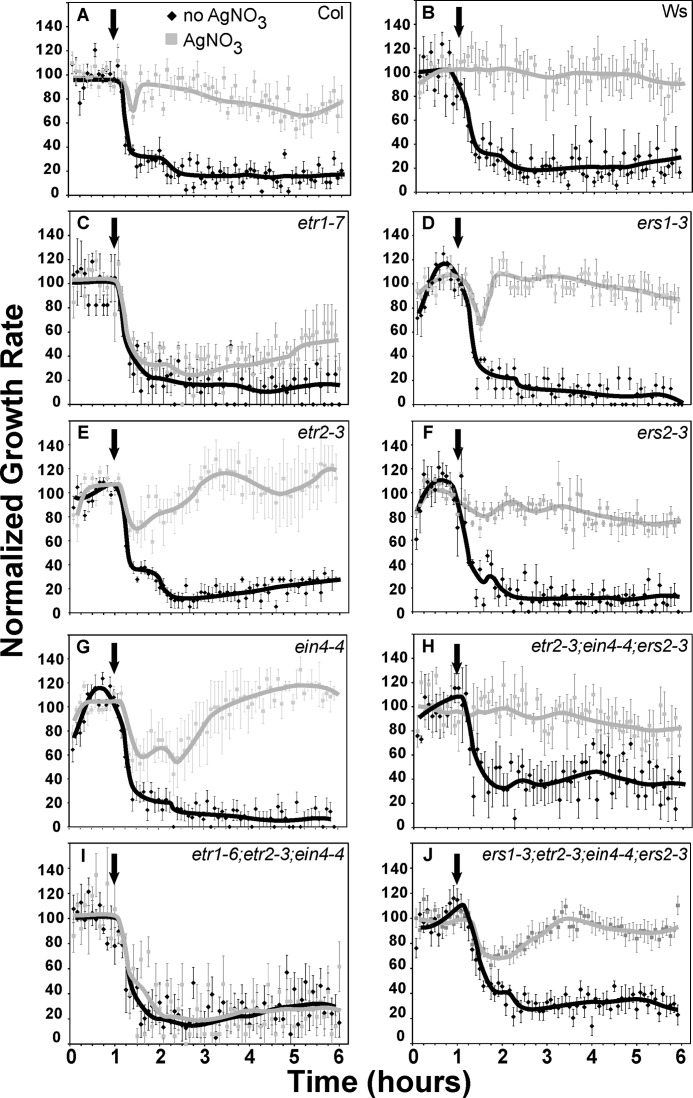

To better define the effects of silver, we examined the ethylene growth response kinetics of seedlings in the presence and absence of 100 μm silver nitrate. Our prior studies have shown that there are two phases to ethylene-induced growth inhibition that are genetically distinct (16, 47). The first phase starts ∼10 min after the addition of ethylene and reaches a plateau in growth rate ∼20 min after the addition of ethylene. This first plateau lasts ∼30 min and is followed by a second phase of growth inhibition that lasts ∼15 min. This second phase requires the presence of the EIN3 and EIL1 transcription factors and ends ∼95 min after the addition of ethylene when a new, lower steady state growth rate is reached (16, 47, 53). At saturating concentrations of ethylene, this second plateau of growth inhibition lasts for as long as ethylene is present (13, 54).

In the absence of silver nitrate, both wild-type and mutant seedlings had growth inhibition kinetics similar to our previous reports (16, 47, 53, 54) including prolonged growth inhibition in the continued presence of ethylene (Fig. 3). Treatment with 100 μm silver nitrate completely blocked long-term responses to ethylene in both Col and Ws wild-type seedlings (Fig. 3, A and B). However, while all responses to ethylene in Ws were blocked by this concentration of silver nitrate (Fig. 3B), Col seedlings still had a very transient response to ethylene (Fig. 3A). Thus, the first phase of growth inhibition may be less sensitive to the antagonistic effects of silver. This is consistent with our prior data showing that the first phase of growth inhibition is much less sensitive to 1-MCP (47), a competitive inhibitor of ethylene (55–58).

FIGURE 3.

The effect of silver nitrate on ethylene growth response kinetics. Each panel (A–J) shows data for one seed line as designated. Seedlings were grown in air for 1 h followed by application of 1 μl/liter ethylene (arrow) for 5 h. The hypocotyl response kinetics of seedlings grown on 100 μm silver nitrate are compared with seedlings grown in the absence of added silver nitrate. Data represent the mean ± S.E. from at least 5 seedlings total from at least four separate experiments. Lines were drawn by hand. Col, Columbia; Ws, Wassilewskija.

We also evaluated the effects of silver nitrate on the ethylene growth response kinetics of single loss-of-function receptor mutants. Strikingly, silver nitrate treatment had no obvious effect on the initial growth inhibition kinetics and only a slight effect on the second phase of growth inhibition of the etr1-7 mutants (Fig. 3C). However, in the continued presence of ethylene, the growth rate of etr1-7 mutants in the presence of silver nitrate started to increase ∼2.5 h after ethylene was introduced. The other single loss-of-function receptor mutants had less severe alterations in their responses to silver nitrate (Fig. 3, D–G). For ers1-3, etr2-3, and ein4-4 (Fig. 3, D, E, G) this was characterized by an attenuated first phase growth inhibition response followed by an increase in growth rate to air pre-treatment levels. Long-term responses to silver nitrate were unaffected in these single loss-of-function mutants. The ers2-3 mutants showed no response to ethylene in the presence of silver nitrate (Fig. 3F).

We also examined the ethylene growth response kinetics of several combinatorial receptor loss-of-function mutants. Application of silver nitrate completely blocked the effects of ethylene on the etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2-3 triple mutants (Fig. 3H). By contrast, the etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutants were unaffected by silver nitrate and exhibited no reversal in growth inhibition (Fig. 3I). This is in agreement with our end-point analyses above (Fig. 2). These differences are not due to alterations in overall receptor levels since both triple mutant backgrounds have comparable levels of ethylene receptor gene expression and ethylene binding (15). Application of silver nitrate to ers1-3;etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2-3 quadruple mutants that only contain ETR1 resulted in attenuated first phase responses (Fig. 3J) much like that observed with the etr2-3 and ein4-4 single mutants.

Together these data indicate that silver nitrate exerts its effects predominantly through ETR1, but that the other isoforms are also involved. Results with the ers1-3;etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2-3 quadruple mutant seedlings show that ETR1 is sufficient to support the inhibitory effects of silver nitrate on long-term ethylene growth responses.

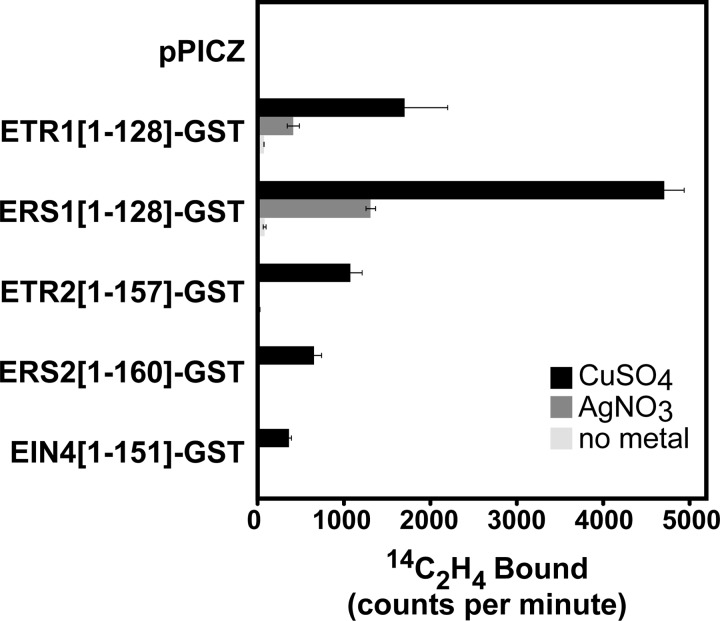

Silver Nitrate Supports Ethylene Binding to Subfamily I Receptors but Not Subfamily II Receptors

Previously we noted that silver can substitute for copper as a cofactor for ethylene binding in the ETR1 receptor (32, 43). This suggests that silver is blocking ethylene signaling through ETR1 by uncoupling the binding event from receptor output. The question remains, why does ETR1 have such a large role in mediating the effects of silver while the other four receptor isoforms play little or no role? One possibility is that silver binds poorly to the other four receptor isoforms and thus has little or no effect on their functionality. A second possibility is that silver does bind to these receptor isoforms, but does not affect stimulus-response coupling through these receptors. To indirectly determine whether or not silver binds to the binding domain of each receptor isoform, we compared the ethylene binding activity of yeast membranes isolated from yeast expressing empty vector or the ethylene-binding domain of each receptor isoform fused to GST. Membranes were incubated with 300 μm CuSO4, 300 μm AgNO3 or no added metal. We have previously shown that in the presence CuSO4 the binding domain of each receptor isoform binds ethylene at levels proportional to receptor expression levels (15). Consistent with these prior results, all five receptor isoforms retained ethylene binding activity with CuSO4 while membranes isolated from yeast expressing the empty pPICZ vector had no detectable ethylene binding above background (Fig. 4, supplemental Table S1). Also consistent with our prior observations (32, 43), silver nitrate supported ethylene binding activity of ETR1[1–128]-GST at ∼30% the activity observed with CuSO4. Silver nitrate also supported similar levels of ethylene binding activity to ERS1[1–128]-GST but failed to support ethylene binding activity to the binding domains of the other three receptor isoforms (Fig. 4, supplemental Table S1). Similar results were obtained in four other experiments. Thus, silver ions support ethylene binding to ETR1 and ERS1 but not ETR2, ERS2, and EIN4.

FIGURE 4.

The effects of copper sulfate and silver nitrate on ethylene binding activity in members of the ethylene receptor family from Arabidopsis. Ethylene binding to equal amounts of yeast membranes isolated from yeast cells expressing the binding domain of each receptor isoform fused to GST or empty vector was compared between samples treated with 14C2H4 (0.1 μl/liter) and identical samples treated with 14C2H4 (0.1 μl/liter) plus 12C2H4 (1000 μl/liter). Samples were pre-incubated for 30 min with either 300 μm copper sulfate, silver nitrate or no metal. Displaceable ethylene binding was determined by subtracting the amount of 14C2H4 bound in the presence of excess 12C2H4 from the amount of 14C2H4 in the absence of added 12C2H4. Data show the mean counts per minute ± S.D.

ETR1 Promoter-driven Expression of Receptors and the Rescue of the Silver Phenotype

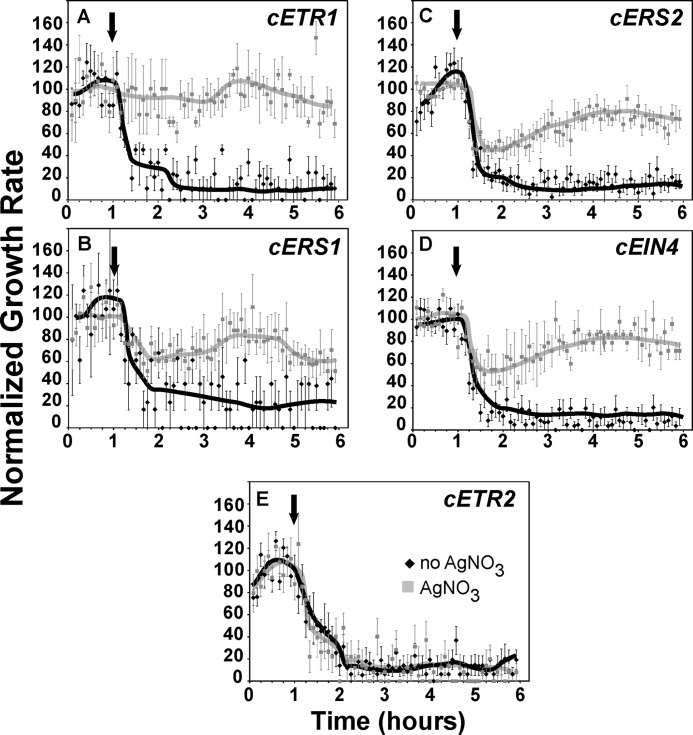

To further delineate the roles of the various receptor isoforms in the effects of silver, we transformed etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutants with cDNA constructs for each of the receptor isoforms from Arabidopsis and examined the ethylene growth responses in the absence and presence of 100 μm silver nitrate (Fig. 5). This triple mutant was chosen because silver nitrate had no obvious effect on ethylene responses in this mutant (Figs. 2 and 3I). In particular, the growth inhibition kinetics were nearly identical whether silver nitrate was present or not (Fig. 3I). To minimize effects from differential expression patterns, the cDNAs for all five receptor genes were placed under the control of the ETR1 promoter. We have previously shown that all five transgenes are expressed and produce functional proteins in this mutant background (20).

FIGURE 5.

The effect of silver nitrate on ethylene growth response kinetics of triple etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 mutants transformed with cDNA for ETR1, ERS2, ERS2 EIN4, or ETR2. All constructs were under the promoter control of ETR1. Each panel (A–E) shows data for one seed line as designated. The transformed seedlings were grown in air for 1 h followed by application of 1 μl/liter ethylene (arrow) for 5 h. The hypocotyl response kinetics of seedlings grown on 100 μm silver nitrate are compared with seedlings grown in the absence of added silver nitrate. Data represent the mean ± S.E. from at least 5 seedlings total from at least four separate experiments. Lines were drawn by hand.

Time-lapse imaging of these transformants showed that the cETR1 transgene completely rescued the silver phenotype so that seedlings had no growth inhibition response when ethylene was applied in the presence of silver nitrate (Fig. 5A). Transformation with the cERS1, cERS2, or cEIN4 transgenes resulted in seedlings that had a partial response to ethylene in the presence of silver nitrate that was characterized by a partial first phase and delayed or incomplete growth recovery to pretreatment rates in the continued presence of ethylene (Fig. 5, B–D). Particularly interesting is that transformation of the etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutant with the cETR2 transgene failed to rescue the silver phenotype so that there was no obvious difference in the ethylene response kinetics in the presence or absence of silver nitrate (Fig. 5E). Similar results were observed with two other cETR2 transformant lines (data not shown). This failure of cETR2 to rescue the silver phenotype is not due to a poorly expressed or a non-functional gene product since cETR2 is expressed at higher levels than either cETR1 or cEIN4 and it rescues other phenotypes including diminished growth in air (20). These results suggest that the importance of each receptor isoform in mediating responses to silver does not correlate with the ability of silver to incorporate into that isoform and support ethylene binding.

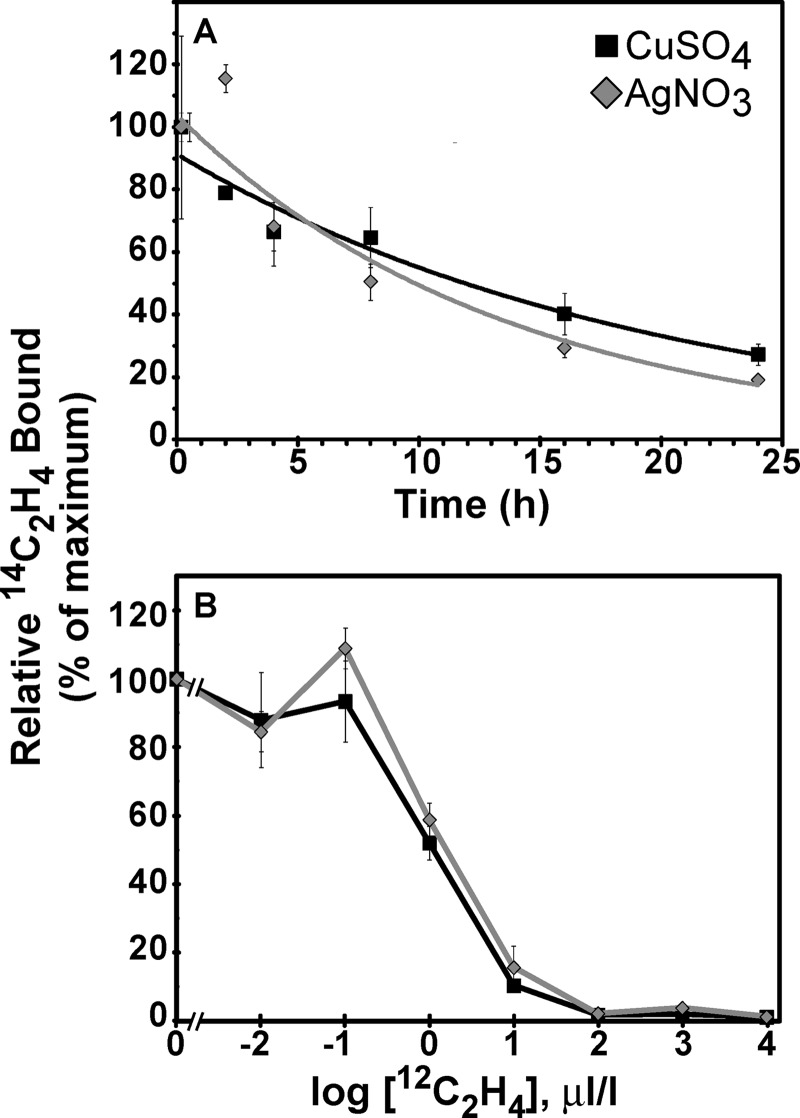

Ethylene Binding Affinity to ETR1 with Copper versus Silver Ions

As in the current study, we have previously noted that ETR1 receptors incubated with silver nitrate have ∼30% the ethylene binding activity of ETR1 receptors incubated with CuSO4 (32, 43). We further investigated this difference in the levels of ethylene binding with silver ions versus copper ions to gain a better idea of how silver ions affect ETR1. We examined the dissociation time-course of 14C2H4 from ETR1[1–128]-GST labeled with 0.1 μl/liter 14C2H4 in the presence of CuSO4 or silver nitrate. Prior studies have shown that ethylene dissociation from intact yeast expressing either the full-length ETR1 or ETR1[1–128]-GST containing copper is slow with a half-time of ∼12.5 h (15, 41). We found that membranes isolated from yeast expressing ETR1[1–128]-GST and incubated with CuSO4 released ethylene with a half-time of ∼12 h compared with an approximate 10 h half-time for release of ethylene for ETR1[1–128]-GST incubated with silver nitrate (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of ethylene binding to ETR1[1–128]-GST with copper sulfate versus silver nitrate. Ethylene binding was determined for membranes isolated from yeast expressing ETR1[1–128]-GST. Membranes were pre-incubated with either 300 μm copper sulfate or silver nitrate for 30 min prior to determining saturable ethylene binding. In both panels, the mean normalized level of 14C2H4 bound ± S.D. is shown. A, time course of 14C2H4 dissociation from ETR1[1–128]-GST was determined after binding was carried out with 0.1 μl/liter 14C2H4. Samples were aired for the indicated times in a chamber with a continuous flow of humidified air and analyzed for 14C2H4 remaining. Data for each incubation condition were normalized to the level of ethylene binding after airing for 10 min. B, ethylene binding levels with 1 μl/liter 14C2H4 in the presence of increasing amounts of 12C2H4 at the indicated concentrations were determined. Data were normalized in each condition to the levels of binding in the absence of added 12C2H4.

To further investigate the effects of silver ions on ETR1, we determined the Kd for ethylene. We compared the effects of CuSO4 and silver nitrate on ethylene binding levels to ETR1[1–128]-GST treated with 1 μl/liter of 14C2H4 in the presence of increasing concentrations of 12C2H4 (Fig. 6B). Only minor differences were observed in the binding curves with either metal. Similar results were obtained in two additional assays (data not shown). Scatchard analysis of all three experiments using the methods of Sisler (51) yielded a Kd value of 1.24 ± 0.26 μl/liter of ethylene with CuSO4 and 0.98 ± 0.19 μl/liter of ethylene with silver nitrate; these values did not differ significantly (p = 0.43). Thus, the reduced level of ethylene binding to ETR1 in the presence of silver nitrate is not due to reduced affinity of ethylene to the receptor in the presence of silver ions.

DISCUSSION

Silver nitrate is known to block ethylene responses in plants (34) yet support ethylene binding to the ETR1 receptor (32, 43). This has led to a model where the larger silver ion occupies the binding site and interacts with ethylene but prevents stimulus-response coupling through the receptors (19, 32, 43, 44).

Whereas silver ions have been shown to alter other processes such as auxin transport (59), the results presented here show that the ethylene receptors mediate the effects of silver on ethylene responses. Unexpectedly we found that ETR1 is sufficient and has the predominant role in blocking ethylene responses in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. Loss-of-function etr1 mutants had long-term reductions in responses to silver that were not seen with single loss-of-function mutants for the other receptor isoforms. These results correlate with the observation that ETR1 has a larger role than the other isoforms in ethylene signaling that leads to control of seedling growth (3, 45). Even though ETR1 has the major role in controlling silver responses, our results indicate that the other isoforms also contribute to this trait. A slightly reduced response to silver was observed in ers1-3, etr2-3, and ein4-4 loss-of-function mutants that was characterized by an attenuated first phase growth inhibition response when ethylene was added. Additionally, the etr1 single loss-of-function mutants still had a partial response to silver while the etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutants had no response to silver indicating that other isoforms contribute to the silver phenotype.

Further support for the importance of ETR1 is our observation that transformation of the etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutant with a transgene for ETR1 rescued the silver phenotype while transformation with cDNA for ERS1, ERS2, or EIN4 only partially rescued the silver phenotype and cETR2 failed to rescue the silver phenotype. It is unclear why this transgene was ineffective at rescuing this trait since it has previously been shown to express a functional protein that rescues other traits (20). These results show that there are differences in the receptors that are important for mediating responses to silver. One explanation for this could simply be that the isoforms are expressed at different levels or with different expression patterns in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. However, this is not likely to be the entire explanation since ERS1 is expressed at nearly the same levels as ETR1 in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings (16) yet loss of ERS1 had a much smaller effect on responses to silver nitrate than loss of ETR1. Also, the cDNA transformants used in this study were under the promoter control of ETR1 to limit differences due to variations in expression patterns. All of these transgenes were expressed at higher levels than cETR1 (20) yet were less effective at rescuing the silver phenotype. Thus, there are functional differences between the receptor isoforms that impact responses to silver. We showed that silver nitrate only supports ethylene binding to subfamily I receptors indicating there are biochemical differences between the different isoforms that may be important in mediating the effects of silver on ethylene perception.

The fact that transgenes for ETR1, ERS1, ERS2, and EIN4 can rescue or partially rescue the silver response in etr1-6;etr2-3;ein4-4 triple mutants while silver only supports ethylene binding to ETR1 and ERS1 suggests that alternative mechanisms for the effects of silver need to be considered. One possibility is that silver binds to ERS2 and EIN4 but blocks ethylene binding to these isoforms. This seems unlikely since silver binds olefins, however, our data do not rule out this possibility. Another possibility is that silver nitrate affects the receptors outside of the binding domain to alter signaling. For instance, there is accumulating evidence that the ethylene receptor dimers function as higher order receptor clusters where the signaling state of one receptor dimer influences the signaling state of neighboring receptor dimers through direct physical interactions (9, 12, 16, 21, 44, 47, 54, 60–63). We have previously proposed that these interactions may underlie the high ethylene sensitivity observed for the first phase of growth inhibition (47). It is thus possible that silver ions affect receptor clustering to subtly enhance output of the receptors to reduce perception of ethylene. This would explain why, in the presence of silver nitrate, ethylene causes a partial growth inhibition response resulting in an attenuated first phase response in some of the receptor loss-of-function mutant combinations and transformants. An argument against this having a major role in this trait is that the ers1-3;etr2-3;ein4-4;ers2-3 quadruple mutants that only contain the ETR1 ethylene receptor isoform still respond normally to the addition of silver nitrate. However, it is possible that it is the clustering of the ETR1 receptors that controls responses to silver ions with the other isoforms differentially modulating this clustering. Thus, silver ions may be having a second effect on the ethylene receptors leading to altered receptor clustering or signal output.

In this study we also examined the effects of silver nitrate on the ETR1 ethylene receptor. Similar to our previous findings, we found that silver nitrate only supported ∼30% of the ethylene binding activity of ETR1 in the presence of CuSO4 (32, 43). This reduced binding with silver nitrate is not due to suboptimal levels of silver since higher levels of silver nitrate do not increase levels of ethylene binding to ETR1 (43). Additionally, the lower binding of ethylene to ETR1 in the presence of silver nitrate is not due to a lower affinity to ethylene since similar Kd values for ethylene binding to ETR1[1–128]-GST were obtained with either metal. These observations are consistent with the suggestion that silver ions have characteristics of a non-competitive inhibitor of ethylene action (34) that would be expected to have no effect on the affinity of the receptors for ethylene. Experimental and computational studies on Group 11 metal-olefin complexes predict that silver-olefin bonds have ∼72% the bond dissociation energy of copper-olefin bonds (64–69). We therefore predicted that ethylene might have a faster half-time of release from ETR1 in the presence of silver nitrate compared with CuSO4. Consistent with this prediction, the half-time of ethylene release from ETR1[1–128]-GST in the presence of silver nitrate was ∼83% the half-time of release in the presence of CuSO4. However, this reduction in the half-time of release is not enough to account for the much lower ethylene binding activity observed with silver nitrate. In addition to slow release kinetics, plants also have a rapid release of ethylene with a half-time of ∼30 min (70, 71) that might be caused by receptor proteolysis (72). Our results show that the exogenously expressed receptors do not have this rapid ethylene release in agreement with prior results on exogenously expressed ethylene receptors (15, 41). Our first time point at 10 min showed that the receptors with silver already had reduced ethylene binding indicating that it is likely the receptors are binding less ethylene rather than releasing ethylene faster.

Thus, the lower ethylene binding activity observed in ETR1 treated with silver nitrate is not due to lower affinity to or faster release from ETR1 receptors containing silver. Therefore, we predict that the number of active ethylene binding sites is lower in ETR1 treated with silver nitrate than with CuSO4. We previously observed that there was one copper per receptor dimer (32) that has led to a model where there is one copper ion per receptor dimer. However, we also noted in this prior study that not all the receptors were active and capable of binding ethylene (32). An alternative model is that each ETR1 receptor contains more than one copper per active receptor dimer with each copper capable of binding ethylene. In this model, we predict that each ETR1 receptor dimer only contains one silver and this leads to the lower levels of ethylene-binding activity in ETR1 receptors exposed to silver nitrate. Alternatively, it is possible that fewer ETR1 proteins contain a metal cofactor in the presence of silver nitrate versus CuSO4. In either model, there are fewer ethylene binding sites generated in the presence of silver that would lead to a reduction in overall binding of ethylene without significantly affecting ethylene binding affinity. More refined analyses will be required to test these models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Brett Case, Elizabeth Helmbrecht, Christina Schmitt, Jalyce Taylor, and Amanda Wehner for technical assistance, Sonia Philosoph-Hadas, Shimon Meir, Gloria Muday, Eric Schaller, and Engin Serpersu for helpful discussions and Nitin Jain, Tian Li, and Tom Masi for technical advice.

This work was supported by an NSF Grant (MCB 0918430) and a BCMB Dept. Hunsicker Research Incentive Award (to B. M. B.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1.

- ETR1

- ethylene receptor 1

- GAF

- cGMP phosphodiesterase/adenyl cyclase/FhlA

- 1-MCP

- 1-methylcyclopropene.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abeles F., Morgan P., Saltveit M. J. (1992) Ethylene in Plant Biology, Second Ed., Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chang C., Kwok S. F., Bleecker A. B., Meyerowitz E. M. (1993) Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science 262, 539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hua J., Meyerowitz E. M. (1998) Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 94, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hua J., Sakai H., Nourizadeh S., Chen Q. G., Bleecker A. B., Ecker J. R., Meyerowitz E. M. (1998) EIN4 and ERS2 are members of the putative ethylene receptor gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1321–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakai H., Hua J., Chen Q. G., Chang C., Medrano L. J., Bleecker A. B., Meyerowitz E. M. (1998) ETR2 is an ETR1-like gene involved in ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5812–5817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang W., Esch J. J., Shiu S. H., Agula H., Binder B. M., Chang C., Patterson S. E., Bleecker A. B. (2006) Identification of important regions for ethylene binding and signaling in the transmembrane domain of the ETR1 ethylene receptor of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 3429–3442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hua J., Chang C., Sun Q., Meyerowitz E. M. (1995) Ethylene insensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science 269, 1712–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hall A. E., Chen Q. G., Findell J. L., Schaller G. E., Bleecker A. B. (1999) The relationship between ethylene binding and dominant insensitivity conferred by mutant forms of the ETR1 ethylene receptor. Plant Physiol. 121, 291–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu Q., Xu C., Wen C. K. (2010) Genetic and transformation studies reveal negative regulation of ERS1 ethylene receptor signaling in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall A. E., Bleecker A. B. (2003) Analysis of combinatorial loss-of-function mutants in the Arabidopsis ethylene receptors reveals that the ers1 etr1 double mutant has severe developmental defects that are EIN2 dependent. Plant Cell 15, 2032–2041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qu X., Hall B. P., Gao Z., Schaller G. E. (2007) A strong constitutive ethylene-response phenotype conferred on Arabidopsis plants containing null mutations in the ethylene receptors ETR1 and ERS1. BMC Plant Biol. 7, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xie F., Liu Q., Wen C. K. (2006) Receptor signal output mediated by the ETR1 N terminus is primarily subfamily I receptor dependent. Plant Physiol. 142, 492–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Binder B. M., O'Malley R. C., Wang W., Zutz T. C., Bleecker A. B. (2006) Ethylene stimulates mutations that are dependent on the ETR1 receptor. Plant Physiol. 142, 1690–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seifert G. J., Barber C., Wells B., Roberts K. (2004) Growth regulators and the control of nucleotide sugar flux. Plant Cell 16, 723–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Malley R. C., Rodriguez F. I., Esch J. J., Binder B. M., O'Donnell P., Klee H. J., Bleecker A. B. (2005) Ethylene-binding activity, gene expression levels, and receptor system output for ethylene receptor family members from Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant J. 41, 651–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Binder B. M., O'Malley R. C., Wang W., Moore J. M., Parks B. M., Spalding E. P., Bleecker A. B. (2004) Arabidopsis seedling growth response and recovery to ethylene. A kinetic analysis. Plant Physiol. 136, 2913–2920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Plett J. M., Cvetkovska M., Makenson P., Xing T., Regan S. (2009) Arabidopsis ethylene receptors have different roles in Fumonisin B1-induced cell death. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 74, 18–26 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Plett J. M., Mathur J., Regan S. (2009) Ethylene receptor ETR2 controls trichome branching by regulating microtubule assembly in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Botany 60, 3923–3933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao X. C., Qu X., Mathews D. E., Schaller G. E. (2002) Effect of ethylene pathway mutations upon expression of the ethylene receptor ETR1 from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 130, 1983–1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim H., Helmbrecht E. E., Stalans M. B., Schmitt C., Patel N., Wen C. K., Wang W., Binder B. M. (2011) Ethylene receptor 1 domain requirements for ethylene responses in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 156, 417–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Q., Wen C. K. (2012) Arabidopsis ETR1 and ERS1 differentially repress the ethylene response in combination with other ethylene receptor genes. Plant Physiol. 158, 1193–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kevany B. M., Tieman D. M., Taylor M. G., Cin V. D., Klee H. J. (2007) Ethylene receptor degradation controls the timing of ripening in tomato fruit. Plant J. 51, 458–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. West A. H., Stock A. M. (2001) Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gamble R. L., Coonfield M. L., Schaller G. E. (1998) Histidine kinase activity of the ETR1 ethylene receptor from Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7825–7829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moussatche P., Klee H. J. (2004) Autophosphorylation activity of the Arabidopsis ethylene receptor multigene family. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48734–48741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Resnick J. S., Wen C. K., Shockey J. A., Chang C. (2006) REVERSION-TO-ETHYLENE SENSITIVITY1, a conserved gene that regulates ethylene receptor function in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7917–7922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dong C. H., Rivarola M., Resnick J. S., Maggin B. D., Chang C. (2008) Subcellular co-localization of Arabidopsis RTE1 and ETR1 supports a regulatory role for RTE1 in ETR1 ethylene signaling. Plant J. 53, 275–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou X., Liu Q., Xie F., Wen C. K. (2007) RTE1 is a Golgi-associated and ETR1-dependent negative regulator of ethylene responses. Plant Physiol. 145, 75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Resnick J. S., Rivarola M., Chang C. (2008) Involvement of RTE1 in conformational changes promoting ETR1 ethylene receptor signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 56, 423–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dong C. H., Jang M., Scharein B., Malach A., Rivarola M., Liesch J., Groth G., Hwang I., Chang C. (2010) Molecular association of the Arabidopsis ETR1 ethylene receptor and a regulator of ethylene signaling, RTE1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40706–40713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rivarola M., McClellan C. A., Resnick J. S., Chang C. (2009) ETR1-specific mutations distinguish ETR1 from other Arabidopsis ethylene receptors as revealed by genetic interaction with RTE1. Plant Physiol. 150, 547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodríguez F. I., Esch J. J., Hall A. E., Binder B. M., Schaller G. E., Bleecker A. B. (1999) A copper cofactor for the ethylene receptor ETR1 from Arabidopsis. Science 283, 996–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thompson J., Harlow R., Whitney J. (1983) Copper(I)-Olefin complexes. Support for the proposed role of copper in the ethylene effect in plants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 3522–3527 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beyer E. M. (1976) A potent inhibitor of ethylene action in plants. Plant Physiol. 58, 268–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burg S. P., Burg E. A. (1967) Molecular requirements for the biological activity of ethylene. Plant Physiol. 42, 144–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sisler E. C. (1976) Ethylene activity of some π-acceptor compounds. Tob. Sci. 21, 43–45 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woeste K. E., Kieber J. J. (2000) A strong loss-of-function mutation in RAN1 results in constitutive activation of the ethylene response pathway as well as a rosette-lethal phenotype. Plant Cell 12, 443–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hirayama T., Kieber J. J., Hirayama N., Kogan M., Guzman P., Nourizadeh S., Alonso J. M., Dailey W. P., Dancis A., Ecker J. R. (1999) RESPONSIVE-TO-ANTAGONIST1, a Menkes/Wilson disease-related copper transporter, is required for ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Cell 97, 383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Binder B. M., Rodríguez F. I., Bleecker A. B. (2010) The copper transporter RAN1 is essential for biogenesis of ethylene receptors in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37263–37270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zimmermann M., Clarke O., Gulbis J. M., Keizer D. W., Jarvis R. S., Cobbett C. S., Hinds M. G., Xiao Z., Wedd A. G. (2009) Metal binding affinities of Arabidopsis zinc and copper transporters: selectivities match the relative, but not the absolute, affinities of their amino-terminal domains. Biochemistry 48, 11640–11654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schaller G. E., Bleecker A. B. (1995) Ethylene-binding sites generated in yeast expressing the Arabidopsis ETR1 gene. Science 270, 1809–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Binder B. M., Chang C., Schaller G. E. (2012) in Annual Plant Reviews, The Plant Hormone Ethylene (McManus M. T., ed), pp. 117–145, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 43. Binder B. M., Rodriguez F. I., Bleecker A. B., Patterson S. E. (2007) The effects of Group 11 transition metals, including gold, on ethylene binding to the ETR1 receptor and growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 581, 5105–5109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Binder B. M., Bleecker A. B. (2003) A model for ethylene receptor function and 1-methylcyclopropene action. ACTA Hort. 628, 177–187 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cancel J. D., Larsen P. B. (2002) Loss-of-function mutations in the ethylene receptor ETR1 cause enhanced sensitivity and exaggerated response to ethylene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 1557–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang W., Hall A. E., O'Malley R., Bleecker A. B. (2003) Canonical histidine kinase activity of the transmitter domain of the ETR1 ethylene receptor from Arabidopsis is not required for signal transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 352–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Binder B. M., Mortimore L. A., Stepanova A. N., Ecker J. R., Bleecker A. B. (2004) Short-term growth responses to ethylene in Arabidopsis seedlings are EIN3/EIL1 independent. Plant Physiol. 136, 2921–2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Parks B. M., Spalding E. P. (1999) Sequential and coordinated action of phytochromes A and B during Arabidopsis stem growth revealed by kinetic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14142–14146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Folta K. M., Spalding E. P. (2001) Unexpected roles for cryptochrome 2 and phototropin revealed by high-resolution analysis of blue light-mediated hypocotyl growth inhibition. Plant J. 26, 471–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schaller G. E., Binder B. M. (2007) in Two-Component Signaling Systems, Part A. Methods in Enzymology (Simon M., Crane B., Crane A., eds), pp. 270–287, Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sisler E. C. (1979) Measurement of ethylene binding in plant tissue. Plant Physiol. 64, 538–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Blankenship S. M., Sisler E. C. (1993) Ethylene binding site affinity in ripening apples. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 118, 609–612 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Binder B. M., Walker J. M., Gagne J. M., Emborg T. J., Hemmann G., Bleecker A. B., Vierstra R. D. (2007) The Arabidopsis EIN3 binding F-Box proteins EBF1 and EBF2 have distinct but overlapping roles in ethylene signaling. Plant Cell 19, 509–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gao Z., Wen C. K., Binder B. M., Chen Y. F., Chang J., Chiang Y. H., Kerris R. J., 3rd, Chang C., Schaller G. E. (2008) Heteromeric interactions among ethylene receptors mediate signaling in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23801–23810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sisler E. C., Dupille E., Serek M. (1996) Effect of 1-methylcyclopropene and methylenecyclopropane on ethylene binding and ethylene action on cut carnations. Plant Growth Reg. 18, 79–86 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sisler E. C., Serek M., Dupille E. (1996) Comparison of cyclopropene, 1-methylcyclopropene, and 3,3-dimethylcyclopropene as ethylene antagonists in plants. Plant Growth Reg. 18, 169–174 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hall A. E., Findell J. L., Schaller G. E., Sisler E. C., Bleecker A. B. (2000) Ethylene perception by the ERS1 protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 123, 1449–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sisler E. C., Serek M. (1999) Growth conditions modulate root-wave phenotypes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 40, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Strader L. C., Beisner E. R., Bartel B. (2009) Silver ions increase auxin efflux independently of effects on ethylene response. Plant Cell 21, 3585–3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gao Z., Schaller G. E. (2009) The role of receptor interactions in regulating ethylene signal transduction. Plant Signal. Behavior 4, 1152–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Grefen C., Städele K., Růzicka K., Obrdlik P., Harter K., Horák J. (2008) Subcellular localization and in vivo interactions of the Arabidopsis thaliana ethylene receptor family members. Mol. Plant 1, 308–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gamble R. L., Qu X., Schaller G. E. (2002) Mutational analysis of the ethylene receptor ETR1. Role of the histidine kinase domain in dominant ethylene insensitivity. Plant Physiol. 128, 1428–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chen Y. F., Gao Z., Kerris R. J., 3rd, Wang W., Binder B. M., Schaller G. E. (2010) Ethylene receptors function as components of high-molecular-mass protein complexes in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 5, e8640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hertwig R., Koch W., Schröder D., Schwarz H., Hrusák J., Schwerdtfeger P. (1996) A comparative computational study of cationic coinage metal-ethylene complexes (C2H4)M+ (M = Cu, Ag, and Au). J. Phys. Chem. 100, 12253–12260 [Google Scholar]

- 65. Roithová J., Schröder D. (2009) Theory meets experiment: Gas-phase chemistry of coinage metals. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 253, 666–677 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sievers M. R., Jarvis L. M., Armentrout P. B. (1998) Transition-Metal Ethene Bonds: Thermochemistry of M+(C2H4)n (M = Ti−Cu, n = 1 and 2) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 1891–1899 [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guo B. C., Castleman A. W. (1991) ) The bonding strength of Ag+(C2H4) and Ag+(C2H4)2 complexes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 181, 16–20 [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schröder D., Schwarz H., Hrusák J., Pyykkö P. (1998) ) Cationic Gold(I) complexes of xenon and of ligands containing the donor atoms oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. Inorg. Chem. 37, 624–632 [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schröder D., Hrusák J., Hertwig R. H., Koch W., Schwerdtfeger P., Schwarz H. (1995) Experimental and theoretical studies of gold(I) complexes Au(L)+ (L = H2O, CO, NH3, C2H4, C3H6, C4H6, C6H6, C6F6). Organometallics 14, 312–316 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sanders I. O., Harpham N. V. J., Raskin I., Smith A. R., Hall M. A. (1991) ) Ethylene binding in wild type and mutant Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Ann. Bot. 68, 97–103 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sisler E. C. (1991) in The Plant Hormone Ethylene (Mattoo A. K., Suttle J. C., eds), pp. 81–99, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chen Y. F., Shakeel S. N., Bowers J., Zhao X. C., Etheridge N., Schaller G. E. (2007) Ligand-induced degradation of the ethylene receptor ETR2 through a proteasome-dependent pathway in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24752–24758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.