Background: The circadian output pathway in cyanobacteria is mediated by a two-component system consisting of SasA/RpaA.

Results: An additional response regulator, RpaB, directly binds to clock-regulated promoters during the night.

Conclusion: RpaB is also a key regulator of the circadian output pathway; RpaA and RpaB function cooperatively.

Significance: Clarification of output pathway details is crucial for understanding the circadian clock.

Keywords: Circadian Clock, Cyanobacteria, Signal Transduction, Transcription Factors, Transcription Regulation, Output Pathway, RpaB, Two-component System

Abstract

The circadian clock of cyanobacteria is composed of KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC proteins, and the SasA-RpaA two-component system has been implicated in the regulation of one of the output pathways of the clock. In this study, we show that another response regulator that is essential for viability, the RpaA paralog, RpaB, plays a central role in the transcriptional oscillation of clock-regulated genes. In vivo and in vitro analyses revealed that RpaB and not RpaA could specifically bind to the kaiBC promoter, possibly repressing transcription during subjective night. This suggested that binding may be terminated by RpaA to activate gene transcription during subjective day. Moreover, we found that rpoD6 and sigF2, which encode group-2 and group-3 σ factors for RNA polymerase, respectively, were also targets of the RpaAB system, suggesting that a specific group of σ factors can propagate genome-wide transcriptional oscillation. Our findings thus reveal a novel mechanism for a circadian output pathway that is mediated by two paralogous response regulators.

Introduction

Endogenous circadian clocks control daily metabolic and physiological cycles to allow many organisms to adapt to the light-dark environment. In most instances, a negative feedback loop that involves central clock genes and that is mediated at the transcriptional and translational levels has been thought to constitute the core system for the generation of consecutive circadian rhythms (1), but the molecular mechanisms of this feedback system remain largely unclear. Cyanobacteria, oxygen-evolving photosynthetic bacteria, are the simplest organisms known to exhibit typical circadian characteristics that are represented most prominently by oscillation of genome-wide gene expression.

In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 (hereafter, Synechococcus), three adjacent genes, kaiABC, have been found to encode a central oscillator (2), and the biochemical functions of KaiABC as clock proteins have been analyzed in detail. For example, KaiC was shown to be autophosphorylated and dephosphorylated during a 24-h period as a result of its consecutive interaction with KaiA and KaiB, which enhance and repress the phosphorylating activity of KaiC, respectively (3–6). Moreover, this circadian cycle of KaiC phosphorylation could be generated in vitro in the presence of only KaiABC and ATP, without de novo transcription or translation (7), suggesting that the KaiC phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle is a self-organizing system that generates circadian rhythm in Synechococcus.

On the other hand, output transcription-translation feedback pathways also appear to be required for maintenance of a stable circadian clock in vivo. The activities of almost all promoters in the Synechococcus genome were initially thought to be regulated by the circadian clock (8); however, recent studies based on microarray analyses have shown that only a proportion (∼30–50%), although still a substantial number, of Synechococcus transcripts, including kaiBC mRNA, undergo circadian oscillation (9, 10). The expression level of clock-regulated genes was found to oscillate markedly under continuous light (LL)2 conditions but rarely under continuous dark conditions, suggesting that transcription-translation rhythm was generated primarily in the LL condition (9, 11, 12). Although various mechanisms, including dynamic contraction of the nucleoid structure (10, 13, 14), have been proposed to explain this feedback regulation, one of the output pathways was shown recently to be mediated by a two-component system composed of SasA (a sensory histidine kinase) and RpaA (an OmpR-type response regulator). Clock-regulated accumulation of kaiBC mRNA was thus not apparent in sasA- or rpaA-null mutants (15, 16). However, neither the target genes that are directly regulated by this two-component system nor the mechanisms by which it regulates clock-dependent gene expression have been identified.

In this study, we report that RpaB, another OmpR-type response regulator, specifically binds to the kaiBC promoter, whereas RpaA cannot directly bind to the promoter either in vitro or in vivo. In addition, we identify rpoD6 and sigF2, which encode group-2 and group-3 σ factors of RNA polymerase, as further targets of the SasA-RpaAB system that might propagate transcriptional oscillation throughout the genome.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Culture

The S. elongatus strain NUC42 (17), which harbors the PkaiBC::luxAB reporter cassette at Neutral Site I, was used as the wild type. For expression of RpaA or RpaB with three copies of the FLAG epitope tag at their COOH termini, a recombinant plasmid described previously (18, 19) was introduced into the NUC 42 strain to yield strains designated RAF and RBF, respectively. Synechococcus cells were grown in BG-11 medium (20) and in a continuous culture system (optical density at 730 nm of ∼0.3) at 30 °C under light at an intensity of ∼40 μmol m−2 s−1. For synchronization of the circadian clock, the culture was acclimatized to two light:dark cycles (12:12 h) and then transferred to LL conditions.

EMSA Analysis

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis was performed as described previously (18). Recombinant RpaA and RpaB proteins were produced in Escherichia coli and purified as described (16, 18). For preparation of probe DNA, the upstream regions of kaiBC and rpoD6 were amplified by PCR with the primers 5′-CATTGACAACTTCGTCAACA-3′ and 5′-GTATTGCCGGCGACGTAGA-3′ for kaiBC and 5′-TTTCGGCTGGTAGAGCTTTT-3′ and 5′-GTCGCGACAGCATGAGCCG-3′ for rpoD6. The purified PCR products were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of T4 polynucleotide kinase (TaKaRa). Probe and competitor DNA for rpoD1 were prepared as described (18). Competitors for different parts of the kaiBC promoter region were also prepared as described (18). The following oligonucleotide sequences, and their complementary sequences, were designed: kaiBC#1 (nucleotides −100 to −71 relative to the transcription initiation site), 5′-GCACATCTTTGTGAGATGTATCGACGGTCT-3′; kaiBC#2 (−60 to −31 relative to the transcription initiation site), 5′-AAACCTGAAAAGGTAAAGGAGGTCTTAAGC-3′; and kaiBC#3 (−20 to +10 relative to the transcription initiation site), 5′-TTCTCTCTTTATCCTGTTAGATGGTTTGAT-3′. For the initial screening of RpaA binding with high amplitude promoters, DNA probes were prepared with the use of Gateway-based clones in which each promoter region was introduced. In brief, the upstream region of each high amplitude gene was amplified by PCR with the primer sets listed in supplemental Table S1. The PCR products then served as templates for a second PCR with the primers 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCG-3′ and 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTAT-3′. The resulting purified PCR products and the pDONR221 donor vector (Invitrogen) were used to construct entry clones with the use of BP (attB × attP) clonase reactions. DNA probes were finally generated by PCR with these entry clones as templates and with the gene-specific (forward) and vector-specific attL1 (reverse) primers listed in supplemental Table S2.

ChIP and qPCR Analysis

Preparation of whole cell extracts from Synechococcus cells, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with mouse monoclonal antibodies to FLAG (Sigma), and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis were performed as described previously (19). The primer sequences are shown in supplemental Table S3.

Bioluminescence Assay

Bioluminescence profiles were examined under the LL conditions after two 12:12-h light:dark cycles as described previously (2).

Immunoblot Analysis

Total protein (10 μg) from RAF and RBF strains was fractionated by SDS-PAGE on a 15% gel, after which the gel was subjected to staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or to immunoblot analysis with mouse antibodies to FLAG as described (18, 19).

RESULTS

RpaA Is Not Involved in Direct Transcriptional Regulation of Circadian Clock-regulated Genes in Cyanobacteria

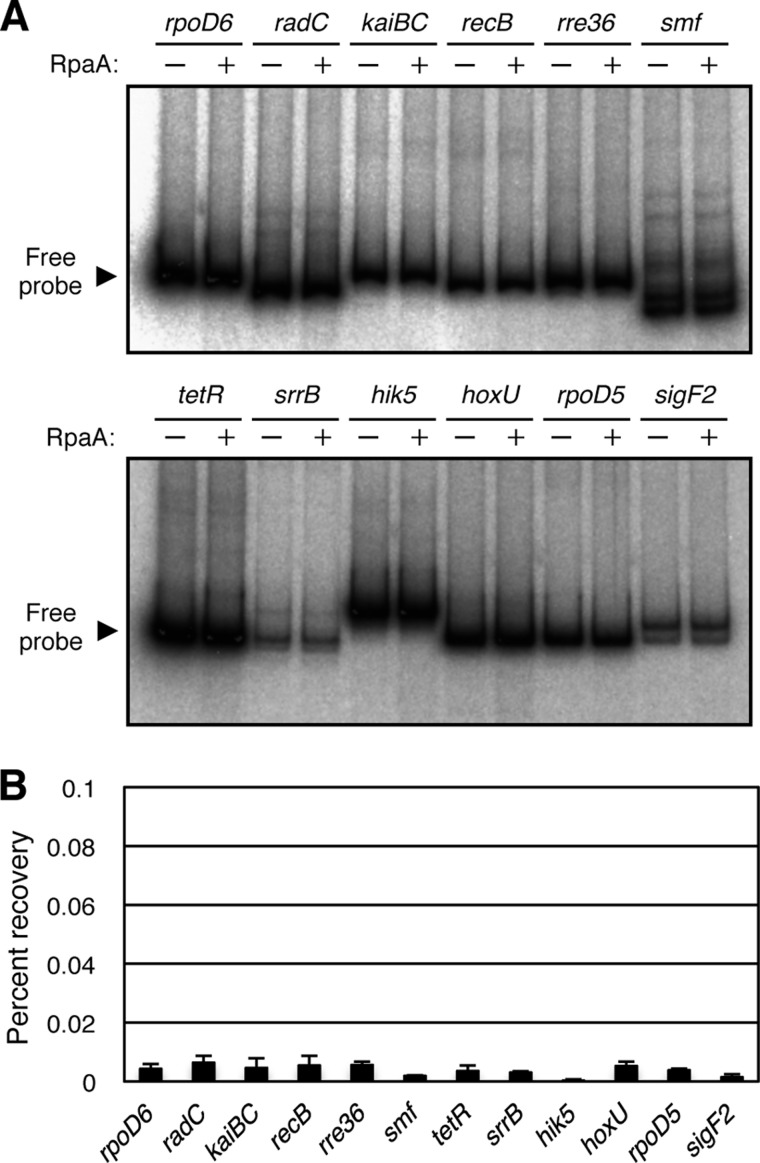

Given the putative role of RpaA as a DNA-binding transcriptional regulator that functions in an output signaling pathway from the KaiABC central clock complex, we initially performed an EMSA to detect the binding of RpaA to target promoters. We selected putative target genes as those whose expression level showed high amplitude oscillation under LL conditions, as determined from microarray data of a previous study (9). However, incubation of recombinant RpaA with 32P-labeled DNA fragments containing the upstream regions of the selected genes did not result in the specific binding of RpaA to any promoters, including that of kaiBC (Fig. 1A), suggesting that RpaA itself does not directly bind to clock-dependent promoters in vitro. A higher concentration of RpaA (7 pmol) as well as in vitro phosphorylation with acetyl phosphate (21, 22) was also examined; however, no major band shifts could not be detected in either experiment (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of RpaA binding with target promoters in vitro and in vivo. A, EMSA analysis with recombinant RpaA. 32P-Labeled DNA fragments (50 fmol) of the promoter regions of rpoD6, radC, kaiBC, recB, rre36, smf, tetR, srrB, hik5, hoxU, rpoD5, or sigF2 were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 0.5 pmol of recombinant RpaA. B, ChIP-qPCR analysis. ChIP was performed with the anti-FLAG antibody and whole cell extracts of the Synechococcus RAF strain expressing RpaA-FLAG grown under continuous white light conditions (40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). The amounts of immunoprecipitated DNA for the rpoD6, radC, kaiBC, recB, rre36, smf, tetR, srrB, hik5, hoxU, rpoD5, and sigF2 promoter regions were determined by qPCR analysis and are expressed as percent recovery relative to the total input DNA. Data are means ± S.D. of four amplifications from two independent experiments.

We then tried to detect the binding of RpaA to putative target promoters in vivo using a ChIP assay that was previously established for Synechococcus (19). ChIP samples were prepared from cultures of the RAF line that expresses RpaA tagged at the COOH terminus with the FLAG epitope (19). After the ChIP reaction, the binding of RpaA to various promoters was measured by qPCR analysis and was expressed as the percentage of input DNA that was recovered in immunoprecipitates. The level of RpaA binding with 12 candidates of the target promoters was low (Fig. 1B). This result suggests that RpaA is also not capable of binding in vivo to promoter regions.

RpaB, in Addition to RpaA, Is a Key Regulator in the Transcriptional Feedback Mechanism of the Cyanobacterial Circadian Clock

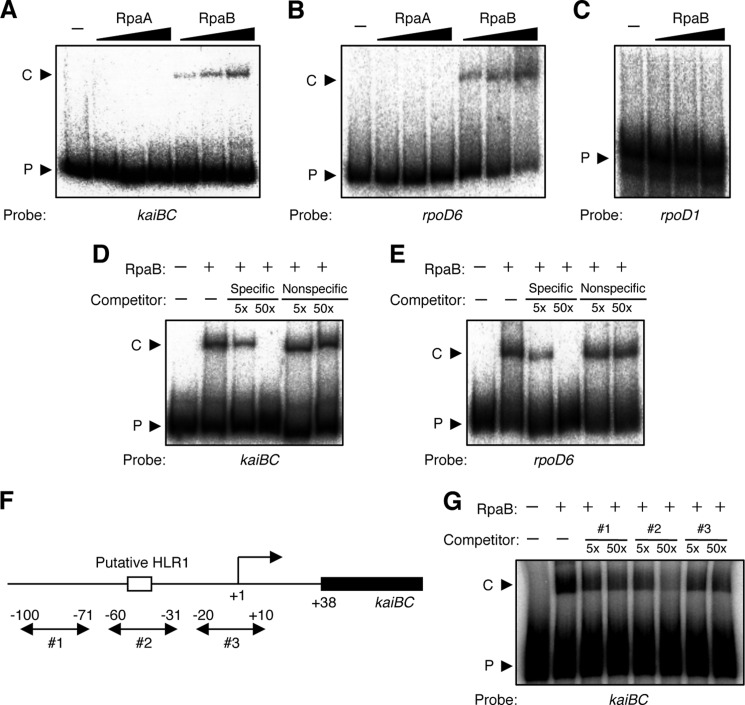

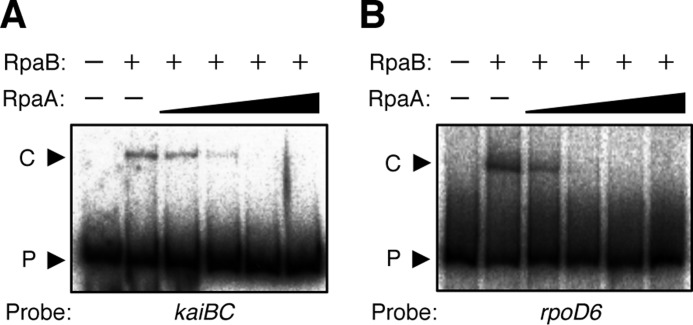

We therefore hypothesized that because RpaA itself does not bind to target promoters, it might function as part of a regulatory complex with one or more other factors. One candidate for such an accessory factor was RpaB, a similar OmpR-type response regulator. RpaA and RpaB were initially identified as regulators related to phycobilisome association in photosynthetic complexes (23), and RpaB was recently found to contribute to high light-dependent transcriptional regulation by binding to a specific DNA sequence known as the high light regulatory 1 (HLR1) element (18, 24). However, a functional role for RpaB in circadian clock-dependent transcriptional regulation has not previously been proposed; the possibility that RpaB might function in circadian output pathways was not examined in a previous genetic screen because RpaB is an essential response regulator in Synechococcus (16). Here, we performed EMSA analysis to examine the binding of RpaA and RpaB to the promoter regions of kaiBC and rpoD6 (which encodes a group-2 σ factor), both of which manifest clock-dependent oscillations of high amplitude (9, 16). Unexpectedly, we found that RpaB, but not RpaA, bound specifically to these promoters (Fig. 2, A and B). As a negative control (Fig. 2C), we confirmed that RpaB did not bind to the clock-independent promoter region of rpoD1, which encodes the group-1 σ factor, as reported previously (18). Specific binding of RpaB to the kaiBC and rpoD6 promoter regions was also confirmed by competition analysis with specific or nonspecific DNA fragments as competitors (Fig. 2, D and E).

FIGURE 2.

Binding of RpaB to clock-dependent promoters in vitro. A–C, EMSA analysis with 0 (−), 1, 2, or 3 pmol of recombinant RpaA or RpaB as well as with 32P-labeled DNA fragments (50 fmol) corresponding to the promoter regions of kaiBC (A), rpoD6 (B), or rpoD1 (C). The upper and lower bands correspond to DNA-protein complexes (C) and free probe (P), respectively. D and E, EMSA analysis for the promoter fragments of kaiBC (D) or rpoD6 (E) in the absence (−) or presence of recombinant RpaB (3 pmol) or 5- or 50-fold molar excesses of specific (kaiBC or rpoD6, respectively) or nonspecific (rpoD1) unlabeled DNA fragments as competitors. F, map of the kaiBC promoter region. Transcriptional initiation site is defined as +1. The putative HLR1 element is shown as an open box. Locations of competitors are shown as arrows 1, 2, and 3. G, EMSA analysis for the promoter fragments of kaiBC in the absence (−) or presence of recombinant RpaB (3 pmol) or 5- or 50-fold molar excesses of unlabeled, double-stranded oligonucleotides (#1–#3) as competitors.

In the kaiBC promoter region, an unusual form of weakly conserved HLR-like element was found at −51 to −44 relative to the transcription initiation site (supplemental Fig. S2; see also “Discussion”). To examine whether this element might be involved in the binding of RpaB, we prepared several oligonucleotide DNA fragments that harbor three different regions of the kaiBC promoter, as competitors for EMSA reactions (Fig. 2F). The binding level of RpaB was reduced specifically in the presence of competitor 2, whose sequence contains the HLR1-like element (Fig. 2G). This result suggests that RpaB can bind to the promoter region of specific clock-regulated genes at the possible HLR1-like element, in a similar manner to its binding to high light-dependent promoters.

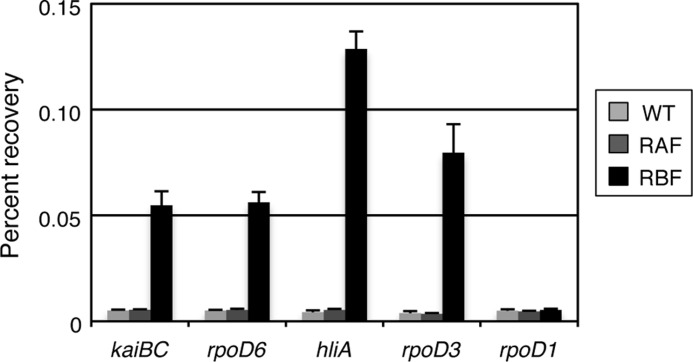

We then examined the binding of RpaA or RpaB to these promoters in vivo with ChIP-qPCR analysis. Samples were prepared from cultures of wild-type (negative control) cells or of transformed (RAF and RBF) lines that express RpaA or RpaB tagged at their COOH termini with the FLAG epitope (18, 19). All of the cells also harbored the PkaiBC-luxAB promoter-reporter element (17), and we confirmed that oscillation of kaiBC promoter activity was not affected by addition of the FLAG tag to RpaA or RpaB (supplemental Fig. S3). The extent of RpaB binding was substantially higher for the clock-regulated kaiBC and rpoD6 promoters as well as for the high light-dependent hliA (encoding a high light-inducible protein) and rpoD3 (encoding a group-2 σ factor) promoters, as described previously (19), than for the rpoD1 promoter used as a negative control (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the level of association of RpaA with the clock-regulated promoters in vivo was much lower than that observed with RpaB (Fig. 3), consistent with our in vitro results showing that RpaA did not bind to the promoter regions of clock-regulated genes.

FIGURE 3.

ChIP and qPCR analysis. ChIP was performed with antibodies to FLAG and with whole cell extracts of wild-type, RAF, or RBF Synechococcus strains (without FLAG, or with expression of RpaA-FLAG, or RpaB-FLAG, respectively) grown under continuous white light conditions (40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). The amounts of immunoprecipitated DNA for the kaiBC, rpoD6, hliA, rpoD3, and rpoD1 promoter regions were determined by qPCR analysis and are expressed as percentage recovery relative to the total input DNA. Data are means ± S.D. of four amplifications from two independent experiments.

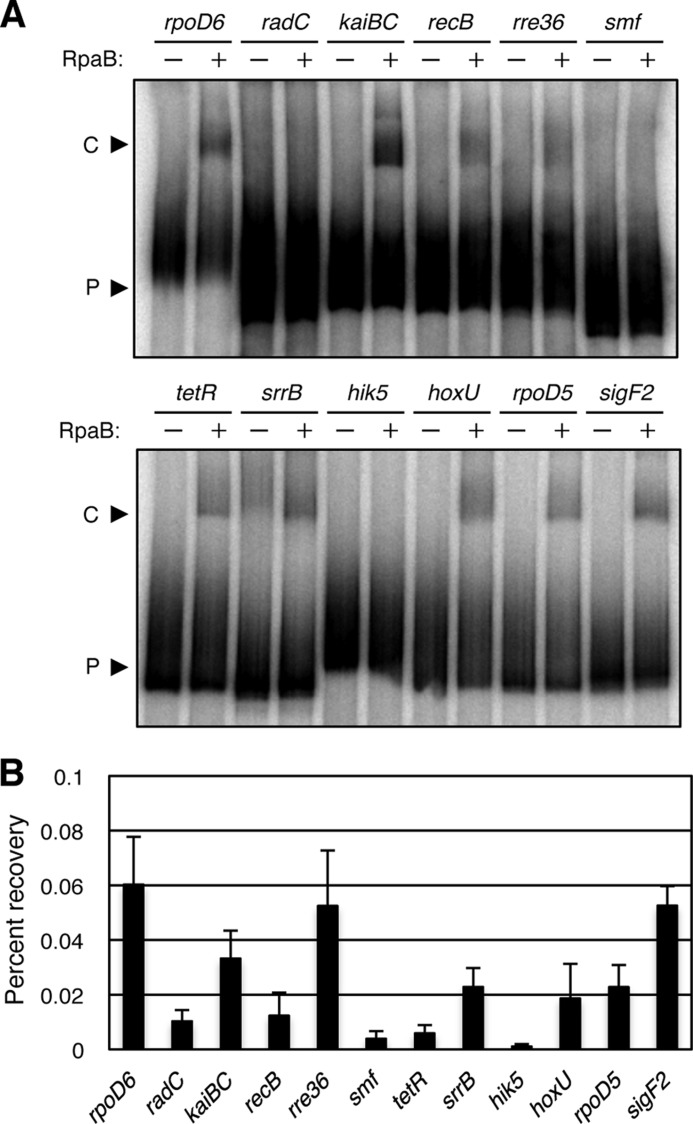

Because RpaB has been identified as a transcriptional regulator with DNA-binding activity for kaiBC and rpoD6 promoters, we further examined whether RpaB is involved in transcriptional regulation of other candidate genes. Binding levels in vitro and in vivo between RpaB and 12 target promoters that showed high amplitude transcript patterns under the LL conditions described in Fig. 1 were investigated with EMSA and ChIP-qPCR analyses. Although binding levels were somewhat different between the two approaches, RpaB-dependent binding patterns were extensive for several promoters, including sigF2 (which encodes another σ factor of group-3) in addition to kaiBC and rpoD6 promoters (Fig. 4, A and B). This result suggests that RpaB can regulate transcription of a specific set of genes as an output regulator of the circadian clock.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of RpaB binding with target promoters in vitro and in vivo. A, EMSA analysis with recombinant RpaB. 32P-Labeled DNA fragments (50 fmol) of the promoter regions of rpoD6, radC, kaiBC, recB, rre36, smf, tetR, srrB, hik5, hoxU, rpoD5, or sigF2 were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 3 pmol of recombinant RpaB. B, ChIP-qPCR analysis. ChIP was performed with the anti-FLAG antibody and whole cell extracts of the Synechococcus RBF strain expressing RpaB-FLAG grown under continuous white light conditions (40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). The amounts of immunoprecipitated DNA for the rpoD6, radC, kaiBC, recB, rre36, smf, tetR, srrB, hik5, hoxU, rpoD5, and sigF2 promoter regions were determined by qPCR analysis and are expressed as percent recovery relative to the total input DNA. Data are means ± S.D. of four amplifications from two independent experiments.

Orchestration of RpaA and RpaB to Generate Transcriptional Oscillation

On the basis of the hypothesis that RpaB contributes to the clock-dependent regulation of gene expression, we next examined whether RpaA and RpaB might function cooperatively at target promoters. We performed EMSA analysis to examine the effect of RpaA on the binding of RpaB to target promoters. The binding of RpaB to 32P-labeled kaiBC or rpoD6 promoter DNA was clearly inhibited by simultaneous addition of RpaA in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5, A and B). Although it seems rather nonstoichiometric because 0.1–0.5 pmol of RpaA could effectively inhibit binding of 3 pmol of RpaB, this observation suggests that RpaA is somehow able to block the interaction of RpaB with circadian clock-regulated promoters. Considering the facts that RpaA was a positive regulator for circadian clock-regulated transcription (16) and that RpaB was identified as a transcriptional repressor of high light-dependent genes (18, 19), this observation also suggested that RpaB might repress transcription of several clock-regulated promoters, including those of kaiBC and rpoD6, during subjective night, and that RpaA might derepress transcription of these genes in the subjective day phase by inducing the dissociation of RpaB from these promoter regions.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of RpaB-promoter interaction by RpaA. EMSA analysis with various amounts of recombinant RpaA (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 pmol) and with 32P-labeled promoter fragments of kaiBC (A) or rpoD6 (B) in the absence or presence of recombinant RpaB (3 pmol).

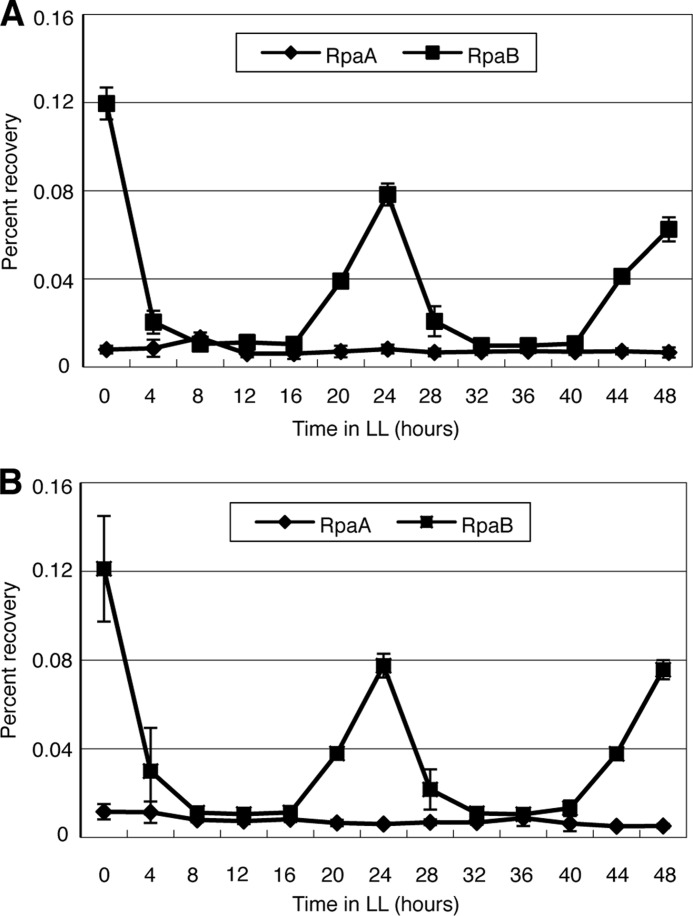

We addressed this hypothetical scheme suggested by our in vitro data by performing in vivo experiments. To examine the binding patterns of RpaA and RpaB during the constant light conditions, we performed ChIP and qPCR analysis of RAF or RBF cells sampled every 4 h from LL0 to LL48. Immunoblot analysis showed that the abundance of both RpaA and RpaB remained constant during the LL conditions (supplemental Fig. S4). ChIP-qPCR analysis revealed that the extent of RpaB binding to the kaiBC promoter region was high at LL0, was decreased markedly at LL4–16, and then increased again to achieve a high level by LL24, with this pattern being repeated during the subsequent 24-h period (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the extent of RpaA binding to the kaiBC promoter region remained low during both subjective day and night phases (Fig. 6A). Similar respective patterns were observed for the binding of RpaB and RpaA to the rpoD6 promoter (Fig. 6B). Together with our in vitro observations, these results supported the notion that RpaB inhibits transcription during the subjective night phase and is released from promoters to allow transcription at the onset of the day phase, and that RpaA promotes likely transcriptional activation by some unidentified mechanism(s).

FIGURE 6.

Oscillation of RpaB binding to the kaiBC and rpoD6 promoters. The time course of the binding of RpaA or RpaB to the kaiBC (A) or rpoD6 (B) promoter regions in RAF and RBF cells, respectively, maintained under LL conditions was examined by ChIP analysis of whole cell extracts. The amounts of DNA for each promoter region immunoprecipitated with antibodies to FLAG were determined by qPCR analysis and are expressed as percentage recovery relative to the total input DNA. Data are means ± S.D. of four amplifications from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

It was shown previously that the post-translational oscillation of KaiC phosphorylation is sufficient to maintain circadian rhythm in cyanobacteria (7). Similar nontranscriptional mechanisms were also identified in several eukaryotes (25, 26). On the other hand, transcriptional-translational feedback loops that have been demonstrated widely in many organisms are required probably to sustain robust circadian outputs. In Synechococcus, RpaA was identified as a positive regulator for genome-wide transcription (16), and it seemed to be simple to analyze the biochemical characteristics between this response regulator and target promoters. However, no direct binding between them could be detected. In this study, we succeeded in identifying another essential response regulator, RpaB, as a key player of this regulation, and we suggest that orchestration of RpaA and RpaB might be important to generate consecutive transcriptional oscillation.

Previous genetic studies showed that the SasA-RpaA two-component system plays a key role in an output pathway of the clock-regulated transcription-translation feedback loop (15, 16). Our in vivo results now suggest that RpaB binds to specific promoters and thereby represses transcription of kaiBC and other target genes during subjective night (∼LL0) and that RpaB is released from these promoters through the effect of RpaA in subjective day (LL4–8). Given that SasA-mediated phosphotransfer to RpaA occurs transiently during the day phase (LL0–8) (16), the phosphorylated form of RpaA may mediate the dissociation of RpaB from target promoters. We tried to explore the interaction between RpaA and RpaB by immunoprecipitation, as well as phosphorylation state of both proteins; however, the underlying mechanisms are still elusive and should be considered in the future study. In addition to kaiBC, this RpaA-RpaB cooperative system regulates the transcription of rpoD6 and sigF2, which encode RNA polymerase σ factors and that may function as a regulator of genome-wide transcriptional oscillation (16, 27). This system operates likely together with other potential mechanisms, such as a circadian-regulated dynamic changes in nucleoid structure (10, 13, 14).

RpaB also functions as a transcriptional repressor in the regulation of several high light-dependent genes, being released from its target promoters to allow activation of transcription under high light conditions (18, 19). Although circadian regulation and high light regulation thus appear similar with regard to the inhibitory effect of RpaB, the target genes for the two regulatory systems differ. The release of RpaB from the promoters of high light-responsive genes and consequent activation of their transcription are therefore not likely to be mediated by SasA-dependent activation of RpaA. This idea is also supported by the difference in structure between the kaiBC promoter and the promoters of high light-dependent genes, which were previously identified by primer extension analysis (18, 19, 28). The two types of promoter include a single, reverse-oriented HLR1 element and repeated, highly conserved HLR1 elements, respectively (supplemental Fig. S2).

Although RpaB appears to function as a negative regulator of clock-dependent transcription that is released from target gene promoters at dawn (LL0–4) to allow activation of transcription, our ChIP analysis showed that the level of RpaB binding to promoters was not restored at dusk (LL12–16), when the transcription of target genes starts to decline. These findings suggest that additional transcriptional regulators, such as LabA and CikA (29, 30), might contribute to transcriptional repression, especially at dusk. Moreover, the peak of expression of kaiBC (LL12) differs from that of rpoD6 (LL8) (9). SasA-dependent phosphorylation of RpaA and the release of RpaB from target promoters occur during LL0–8 and would be expected to affect both genes similarly. The expression of rpoD6 might therefore be specifically repressed during LL10–12 by an unknown mechanism.

In conclusion, our results have identified another response regulator, RpaB, in addition to the previously demonstrated SasA-RpaA two-component system. These two response regulators might cooperatively regulate transcription of specific target genes. Although detailed molecular mechanisms such as the phosphorylation state of both response regulators as well as direct interaction of the two proteins in vivo should be studied in more detail, our findings will help in the understanding of the circadian output pathway in cyanobacterial cells that optimizes photosynthetic and metabolic activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Masato Nakajima, Michinori Mutsuda, Yoriko Murayama, and Tokitaka Oyama for providing materials and for discussions.

This work was supported by a Special Coordination Fund for Promoting Science and Technology (to M. H.) and Grant-in-aid 16GS0304 for Creative Scientific Research (to K. T.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; by Grants-in-aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 21370015 (to K. T.), 21770034 (to M. H.), 20370072, 22657043, and 21010517 (to H. I.), by the COE (Center of Excellence) StartUp Program of Chiba University (to K. T.), by Waseda University Grant 2010A-503 for Special Research Projects (to H. I.), by the Asahi Glass Foundation (to H. I.), and by the Cooperative Research Program of “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices” (to M. H. and K. T.).

This article contains Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1–S3.

- LL

- continuous light

- SasA

- Synechococcus adaptive sensor A

- RpaA and RpaB

- Regulator of phycobillisome association A and B

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- HLR1

- high light regulatory 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Young M. W., Kay S. A. (2001) Time zones: a comparative genetics of circadian clocks. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 702–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ishiura M., Kutsuna S., Aoki S., Iwasaki H., Andersson C. R., Tanabe A., Golden S. S., Johnson C. H., Kondo T. (1998) Expression of a gene cluster kaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science 281, 1519–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwasaki H., Nishiwaki T., Kitayama Y., Nakajima M., Kondo T. (2002) KaiA-stimulated KaiC phosphorylation in circadian timing loops in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15788–15793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams S. B., Vakonakis I., Golden S. S., LiWang A. C. (2002) Structure and function from the circadian clock protein KaiA of Synechococcus elongatus: a potential clock input mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15357–15362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kageyama H., Kondo T., Iwasaki H. (2003) Circadian formation of clock protein complexes by KaiA, KaiB, KaiC, and SasA in cyanobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2388–2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nishiwaki T., Satomi Y., Nakajima M., Lee C., Kiyohara R., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Go M., Iwasaki H., Takao T., Kondo T. (2004) Role of KaiC phosphorylation in the circadian clock system of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13927–13932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakajima M., Imai K., Ito H., Nishiwaki T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T. (2005) Reconstitution of circadian oscillation of cyanobacterial KaiC phosphorylation in vitro. Science 308, 414–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu Y., Tsinoremas N. F., Johnson C. H., Lebedeva N. V., Golden S. S., Ishiura M., Kondo T. (1995) Circadian orchestration of gene expression in cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 9, 1469–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ito H., Mutsuda M., Murayama Y., Tomita J., Hosokawa N., Terauchi K., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H. (2009) Cyanobacterial daily life with Kai-based circadian and diurnal genome-wide transcriptional control in Synechococcus elongatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14168–14173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vijayan V., Zuzow R., O'Shea E. K. (2009) Oscillations in supercoiling drive circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22564–22568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomita J., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H. (2005) No transcription-translation feedback in circadian rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation. Science 307, 251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hosokawa N., Hatakeyama T. S., Kojima T., Kikuchi Y., Ito H., Iwasaki H. (2011) Circadian transcriptional regulation by the posttranslational oscillator without de novo clock gene expression in Synechococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15396–15401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith R. M., Williams S. B. (2006) Circadian rhythms in gene transcription imparted by chromosome compaction in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8564–8569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Woelfle M. A., Xu Y., Qin X., Johnson C. H. (2007) Circadian rhythms of superhelical status of DNA in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18819–18824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iwasaki H., Williams S. B., Kitayama Y., Ishiura M., Golden S. S., Kondo T. (2000) A kaiC-interacting sensory histidine kinase, SasA, necessary to sustain robust circadian oscillation in cyanobacteria. Cell 101, 223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takai N., Nakajima M., Oyama T., Kito R., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H. (2006) A KaiC-associating SasA-RpaA two-component regulatory system as a major circadian timing mediator in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12109–12114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishimura H., Nakahira Y., Imai K., Tsuruhara A., Kondo H., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T. (2002) Mutations in KaiA, a clock protein, extend the period of circadian rhythm in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Microbiology 148, 2903–2909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seki A., Hanaoka M., Akimoto Y., Masuda S., Iwasaki H., Tanaka K. (2007) Induction of a group 2 σ factor, RPOD3, by high light and the underlying mechanism in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36887–36894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hanaoka M., Tanaka K. (2008) Dynamics of RpaB-promoter interaction during high light stress, revealed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Plant J. 56, 327–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rippka R. (1988) Isolation and purification of cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 167, 3–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCleary W. R., Stock J. B. (1994) Acetyl phosphate and the activation of two-component response regulators. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 31567–31572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shin S., Park C. (1995) Modulation of flagellar expression in Escherichia coli by acetyl phosphate and the osmoregulator OmpR. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4696–4702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ashby M. K., Mullineaux C. W. (1999) Cyanobacterial ycf27 gene products regulate energy transfer from phycobilisomes to photosystems I and II. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 181, 253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kappell A. D., van Waasbergen L. G. (2007) The response regulator RpaB binds the high light regulatory 1 sequence upstream of the high-light-inducible hliB gene from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Arch. Microbiol. 187, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Neill J. S., Reddy A. B. (2011) Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature 469, 498–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Neill J. S., van Ooijen G., Dixon L. E., Troein C., Corellou F., Bouget F. Y., Reddy A. B., Millar A. J. (2011) Circadian rhythms persist without transcription in a eukaryote. Nature 469, 554–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Golden S. S. (2003) Timekeeping in bacteria: the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 535–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kutsuna S., Nakahira Y., Katayama M., Ishiura M., Kondo T. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of the circadian clock operon kaiBC by upstream regions in cyanobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 1474–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taniguchi Y., Katayama M., Ito R., Takai N., Kondo T., Oyama T. (2007) labA: a novel gene required for negative feedback regulation of the cyanobacterial circadian clock protein KaiC. Genes Dev. 21, 60–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taniguchi Y., Takai N., Katayama M., Kondo T., Oyama T. (2010) Three major output pathways from the KaiABC-based oscillator cooperate to generate robust circadian kaiBC expression in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3263–3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.