Background: Human VIMP/SelS is a selenoprotein involved in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation.

Results: The cytosolic domain of VIMP constitutes an extended α-helical segment followed by an intrinsically disordered region harboring redox activity.

Conclusion: VIMP is a non-globular protein with a likely reductase function.

Significance: These findings provide new mechanistic insight into the molecular function of VIMP.

Keywords: Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Endoplasmic Reticulum(ER), Protein Degradation, Protein Misfolding, Redox, Endoplasmic Reticulum-associated Degradation (ERAD), Selenoprotein S (SelS), VCP-interacting Membrane Protein (VIMP), p97

Abstract

The human selenoprotein VIMP (VCP-interacting membrane protein)/SelS (selenoprotein S) localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and is involved in the process of ER-associated degradation (ERAD). To date, little is known about the presumed redox activity of VIMP, its structure and how these features might relate to the function of the protein in ERAD. Here, we use the recombinantly expressed cytosolic region of VIMP where the selenocysteine (Sec) in position 188 is replaced with a cysteine (a construct named cVIMP-Cys) to characterize redox and structural properties of the protein. We show that Cys-188 in cVIMP-Cys forms a disulfide bond with Cys-174, consistent with the presence of a Cys174-Sec188 selenosulfide bond in the native sequence. For the disulfide bond in cVIMP-Cys we determined the reduction potential to −200 mV, and showed it to be a good substrate of thioredoxin. Based on a biochemical and structural characterization of cVIMP-Cys using analytical gel filtration, CD and NMR spectroscopy in conjunction with bioinformatics, we propose a comprehensive overall structural model for the cytosolic region of VIMP. The data clearly indicate the N-terminal half to be comprised of two extended α-helices followed by a C-terminal region that is intrinsically disordered. Redox-dependent conformational changes in cVIMP-Cys were observed only in the vicinity of the two Cys residues. Overall, the redox properties observed for cVIMP-Cys are compatible with a function as a reductase, and we speculate that the plasticity of the intrinsically disordered C-terminal region allows the protein to access many different and structurally diverse substrates.

Introduction

To ensure the structural fidelity of the proteins that leave the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)4 by vesicular transport along the exocytic pathway, ER chaperones and folding factors assist the folding of newly synthesized proteins. Still, protein misfolding is a common occurrence for both mutant and wild-type proteins. Irreversibly misfolded proteins and subunits of unassembled oligomers are degraded by the process known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (for recent reviews see Refs. 1, 2). This multistep process involves substrate recognition by chaperones, dislocation to the cytosol through a presumed proteinacious and currently unknown retrotranslocation channel (the “dislocon”), polyubiquitination by E3 ubiquitin ligases and degradation by the proteasome.

Central components of the ERAD system are conserved between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cells (3, 4). In the ER lumen these components include the abundant chaperone BiP and associated ERdj co-chaperones, members of the PDI family of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases, as well as lectins and sugar-modifying enzymes such as the EDEM proteins, OS-9 and XTP3-B (see e.g. Ref. 5–7). In the ER membrane, dislocon candidates include the Derlin proteins as well as E3 ubiquitin ligases (1, 2). In mammalian cells, as many as 24 transmembrane E3 ligases may exist (8), although only about 10 of these have been verified to function in ERAD (1, 2). On the cytosolic side of the ER membrane the different pathways all seem to converge at p97 (also known as VCP), an AAA ATPase that can extract polyubiquitinated substrates as they emerge from the ER (9). Apart from these key components, various adaptor proteins, E2 conjugases and deubiquitinating enzymes also participate. The complexity of the mammalian ERAD system has recently become even more apparent from an integrated systems-based approach, which revealed a number of new genes in ERAD as well as physical and functional interaction maps between ERAD components (10).

The conformational requirements of the polypeptide chain that allow dislocation from the ER are not known, but it is generally presumed that most substrates are at least partially unfolded. In this connection it is interesting to note that several ERAD substrates contain disulfide bonds, which implies a potential need for reduction prior to dislocation. Indeed, it has been shown that perturbation of the ER redox environment can influence the dislocation process so that oxidizing conditions inhibit dislocation, whereas reducing conditions most often promote the process (11, 12). Accordingly, a variety of substrates become reduced prior to degradation (11–15). Presently, the PDI-family member ERdj5 is the only known disulfide reductase involved in ERAD (16, 17). The identity of the electron donor(s) for reduction in the ER is unknown. An ERdj5-interacting flavoprotein, ERFAD, is a potential candidate (18). However, the exact function during ERAD of this protein and its interaction partner, the newly discovered ERp90 (19), is presently unknown.

VIMP (VCP-interacting membrane protein, also known as Selenoprotein S (SelS)) is one of only 25 human selenoproteins (20). The protein contains a short N-terminal ER-lumenal tail, followed by a predicted transmembrane region encompassing residues 26–48 (21, 22) (Fig. 1A). The single selenocysteine (Sec) is found in the penultimate position as residue 188 in the cytosolic domain. Based on the special chemical properties of selenocysteine, e.g. the low pKa value of the side chain and its high nucleophilicity (20, 23), like other selenoproteins VIMP is expected to carry out a redox function. Apart from an antioxidant activity of P. falciparum VIMP observed in vitro (24), the redox properties of VIMP remain unexplored.

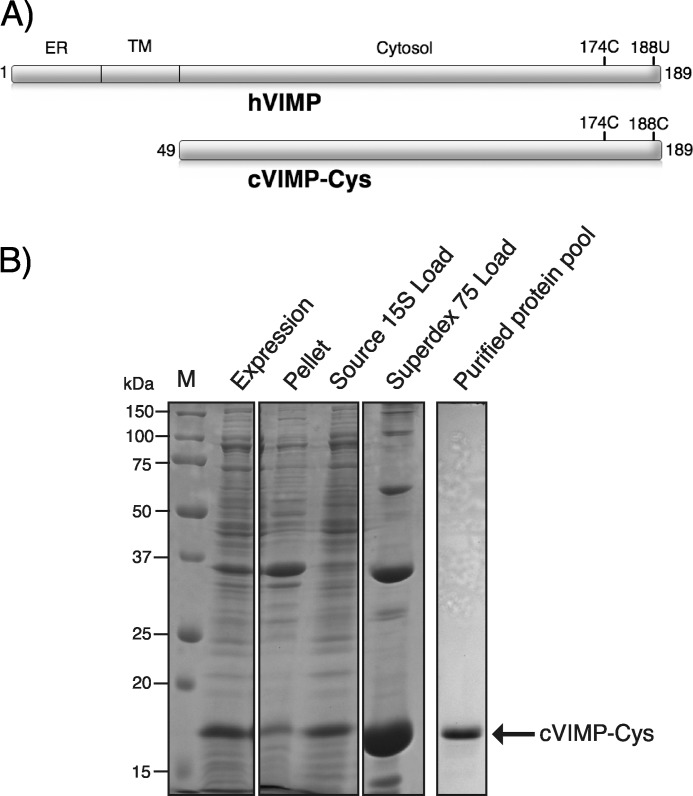

FIGURE 1.

Overview of VIMP and purification of the cVIMP-Cys construct. A, schematic representation of human VIMP (hVIMP) and the cytosolic construct (cVIMP-Cys) used in this study. ER, endoplasmic reticulum region; TM, transmembrane region; Cytosol, cytosolic region. The position of Cys-174 (174C) and Sec188 (188U)/Cys188 (188C) is marked. B, purification of recombinantly expressed cVIMP-Cys. 18% reducing Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of Expression (total cell lysate), Pellet (after centrifugation of total lysate), Source 15S Load (supernatant from centrifugation of total lysate), Superdex 75 Load (pooled and concentrated fractions from Source 15S) and Purified protein pool (pooled fractions from Superdex 75). The arrow indicates the position of cVIMP-Cys and M denotes molecular weight marker.

VIMP is a known interaction partner of p97 (22), as well as Derlin-1 and -2 (22, 25, 26), and therefore likely provides a physical link between these important ERAD factors at the ER membrane. In accordance with a function in ERAD, VIMP co-immunoprecipitates polyubiquitinated proteins especially under conditions of ER stress (22). Moreover, VIMP has recently been shown to co-immunoprecipitate with another selenoprotein, SelK, which is also implicated in ERAD (25). Interestingly, VIMP, SelK, and the mitochondrial protein Romo1 have been found to constitute a widespread eukaryotic selenoprotein family, which among other features has in common the presence of a positively charged, glycine-rich region located close to the C terminus (25).

The current study was performed to further our understanding of central structural and biochemical properties of VIMP. We found that the purified cytosolic domain of VIMP constitutes a non-globular molecule with α-helical and intrinsically disordered regions. A particularly well-conserved region at the C terminus encompasses the active site residues, which have redox properties compatible with a function as a reductase. The molecular insights gained here will provide a strong starting point for future cell biological studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Primers

Based on the sequence of the human VIMP cDNA (IMAGE2967406 (2553); GeneService), a sequence-optimized construct for Escherichia coli expression was synthesized by GeneScript and cloned into pUC57, generating the pLE345 plasmid. Based on this construct and pET-21b (Novagen), we made the pET-21b-cVIMPopt-Cys (pLE358) plasmid for expression of cVIMP-Cys. Using pLE345 as a template, the sequence encoding residues 49–189 of VIMP were PCR amplified using the NdeI-cVIMPopt (5′-AAAAAACATATGCAGAAACTGAGCGCCCGTCTGCGC-3′) and cVIMPopt-Cys-EcoRI (5′-AAAAAAGAATTCTTAGCCGCAGCCGCCGCTGCTCGGGCC-3′) primers. The latter substituted the TGA codon that encodes the selenocysteine with a Cys codon and included a TGA stop codon following the codon for Gly-189. The resulting fragment was subcloned into the bacterial expression vector pET-21b using the NheI and EcoRI restriction sites. The plasmid was sequenced to confirm the correct DNA sequence. The pET-21b-His6-(Mm)p97(1–199) plasmid (pLE329) for expression of mouse His6-p97(1–199) has been described before (27).

Protein Expression and Purification

pLE358 was transformed into competent BL21(DE3) cells and plated on Luria Broth (LB) agar containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Amp). One colony was inoculated in 125 ml of LB media containing 100 μg/ml Amp and grown overnight at 37 °C. The overnight culture was diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (A600) of 0.1 in LB media with Amp. The culture was then propagated to A600 = 1 at 37 °C in an orbital shaker. Protein expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 h at 37 °C and harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of buffer A (50 mm Na-phosphate, 25 mm NaCl, pH 8.0) with 1 mm PMSF, 5 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) per liter of culture media and frozen at −20 °C until further use. Next, cells were sonicated and subjected to centrifugation for 1 h at 27,000 × g. The filtered supernatant was applied to a Source 15S cation exchange chromatography column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with buffer A at 4 °C. After loading and washing with 25 column volumes buffer A, cVIMP-Cys was eluted with a linear gradient over 20 column volumes against buffer B (50 mm Na-phosphate, 1 m NaCl, pH 8.0). In this gradient, cVIMP-Cys eluted at ≈300 mm NaCl. The fractions with the highest concentration of cVIMP-Cys were pooled and concentrated to A280 ≈2.5. As a final purification step, 250 μl of protein sample was loaded onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) and eluted isocratically at 4 °C in buffer C (50 mm Na-phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.0). Protein for NMR experiments was prepared by inoculation of a colony into 125 ml of non-labeled M9 minimal media containing 100 μg/ml Amp and grown at 37 °C to A600 = 2. For uniform 15N and 13C-labeling, the preculture was diluted to A600 = 0.2 in 15N,13C-labeled M9 minimal media and propagated at 37 °C. At A600 = 1 cells were induced with 1 mm IPTG for 3 h at 37 °C. Purification of 15N,13C-cVIMP-Cys was carried out exactly as for the non-labeled protein.

For expression of the p97 N-domain, pLE329 was transformed and propagated at 37 °C exactly as described for pLE358. At A600 = 0.75, protein expression was induced with 1 mm IPTG for 3 h at 30 °C and harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mm Na-phosphate, 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, pH 8.0 with 1 mm PMSF and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) per liter of culture media. Next, lysozyme was added to the cells to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. Upon incubation on ice for 1 h, cells were sonicated and subjected to centrifugation for 1 h at 27,000 × g. The supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA beads for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were transferred to an empty column and washed by gravity flow with 10 column volumes of 50 mm Na-phosphate, 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, pH 8.0. The protein was eluted with 2 column volumes of 50 mm Na-phosphate, 300 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, pH 8.0. The fractions containing mouse His6-p97(1–199) (hereafter referred to as p97N) were dialyzed into buffer C overnight at 4 °C. Next, the filtered protein pool was applied onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column and eluted isocratically in buffer C at 4 °C. Fractions containing purified p97N were pooled and concentrated for NMR spectroscopy.

Protein Concentration Determination

The concentration of the purified cVIMP-Cys protein was determined from its absorbance at 280 nm using the theoretical extinction coefficient 14,105 m−1 cm−1 (28). A theoretical extinction coefficient of 7,450 m−1 cm−1 was used for p97N.

4-Acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (AMS)Shift Assay

75 μl (4 μm) of protein was precipitated with 20% TCA for at least 30 min at 4 °C, and spun at 16,100 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet dissolved in 20 μl of AMS buffer (400 mm Tris, 1.6% SDS, 0.04% bromcresol purple (pH indicator with buffer point at pH 6.8, Fluka), 15 mm AMS). The pH of the solution was then increased by titration with 1.5 m Tris, pH 8.8 until a color shift appeared. Samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h, followed by addition of non-reducing loading buffer. The samples were boiled for 5 min prior to loading on SDS-PAGE gels.

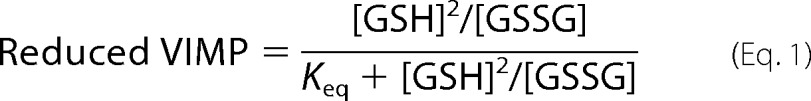

Redox Equilibrium between cVIMP-Cys and Glutathione

100 μl (4.5 μm) of protein was equilibrated with different ratios of [GSH]2/[GSSG] in 50 mm Na-phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.0 at 25 °C for 16 h under an argon atmosphere. The concentration of GSSG was kept at 0.1 mm in all samples, whereas the concentration of GSH was varied from 0.6 mm to 17.8 mm resulting in [GSH]2/[GSSG] ratios ranging from 3.2 mm to 3160 mm. The total reaction volume was 125 μl. Upon incubation, 50 μl was quenched with 100 mm HCl and prepared for HPLC to determine the concentrations of GSH and GSSG. The samples were spun at 16,100 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant run on a reversed-phase C18 column (Vydac 218 TP) with 95% buffer D (0.1% TFA in ddH2O) and 5% buffer E (0.1% TFA, 10% acetonitrile). The relative peak areas corresponding to GSH and GSSG were calibrated to a set of GSH and GSSG standard solutions. The concentration of the GSH standard was determined using the absorbance of Ellmann's reagent (10 mm 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid), 0.5 m K-phosphate, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.3) at 412 nm and the extinction coefficient 14,150 m−1 cm−1 (29). The concentration of the GSSG standard was calculated from the absorbance at 248 nm and the extinction coefficient 382 m−1 cm−1 (30). From the resulting standard curves the actual concentrations of GSH and GSSG in each reaction mixture were calculated.

The remaining 75 μl of the reaction mixture was quenched with 20% TCA and modified with AMS according to the procedure described for the AMS shift assay. The AMS-modified samples were run on 18% SDS-PAGE gels and Coomassie-stained prior to quantification using ImageJ (31). The determined fraction of reduced cVIMP-Cys was plotted against the determined [GSH]2/[GSSG] and fitted according to Equation 1 to obtain Keq.

|

The equilibrium redox potential of cVIMP-Cys was then calculated with the Nernst equation (Equation 2) using the glutathione standard potential of −0.240 V at pH 7.0 and 25 °C (32):

All data points were normalized to take into account that in this particular experiment a small fraction of AMS-resistant protein was observed in the sample treated with the reducing agent Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (sample 1).

Reduction of cVIMP-Cys by the Thioredoxin System

Active recombinant rat thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) was purchased from IMCO (product TR-03-B) and recombinant human thioredoxin (Trx) was from Prospec (product Pro-569). The enzymes were diluted from the stock concentrations provided by the supplier. Measurements were performed on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 35 UV-Vis spectrometer at 25 °C. Buffers were flushed with argon and the spectrometer was blanked on an empty dry cuvette. Measurements were initiated on a cuvette containing 155 μm β-NADPH (Sigma) in buffer C (50 mm Na-phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.0). The amount of disulfide reduction was calculated from the decrease in absorbance and the extinction coefficient for β-NADPH (6200 m−1 cm−1). The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was then followed over time during the subsequent addition of (in final concentrations) 0.1 μm TrxR, 25 μm cVIMP-Cys, and 0.5–1 μm Trx. At these concentrations, the assay was linearly dependent on Trx concentration.

Analytical Gel Filtration

Analytical gel filtration was performed by applying 220 μl of protein sample (54 μm) on a Superdex 75 column equilibrated with buffer F (50 mm Na-phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, pH 8.0) at 4 °C. The column was calibrated with a set of globular protein standards (Gel Filtration Calibration kit, Pharmacia). All protein samples were eluted isocratically at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. cVIMP-Cys was reduced for at least 2.5 h with 2 mm DTT and eluted from the column equilibrated in buffer F containing 2 mm DTT. Samples for AMS modification were quenched by TCA addition as soon as they eluted from the column. Subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis verified the expected redox state of each sample (data not shown). The results were analyzed by plotting the logarithm of the molecular weight for each standard protein versus their partition coefficient Kav,

|

where Ve is the elution volume, V0 is the void volume, and Vt is the column volume. A linear fit to the data points of the standard proteins yielded the calibration curve used to calculate the apparent molecular mass of oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys.

CD Spectroscopy

Protein samples were at equal concentration (8.4 μm) buffered in 50 mm Na-phosphate pH 7.0 for the oxidized and 50 mm Na-phosphate, 1 mm TCEP, pH 7.0 for the reduced protein. For reduction, the sample was incubated in the reducing buffer for 90 min at room temperature prior to recording. Samples for AMS shift assays were quenched by TCA addition after each measurement. Subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis verified the expected redox state of each sample (data not shown).

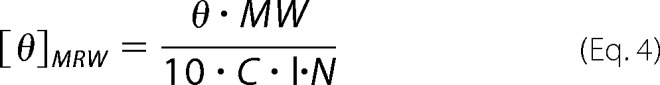

Measurements were done in a 350 μl quartz cuvette with 1 mm light path at 5 °C. The spectra were recorded as an accumulation of 12 scans from 250 nm to 190 nm at a scan rate of 20 nm/min on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with a PTC-423S temperature control device. Upon recording, all data sets were subtracted the buffer baseline and noise reduced with a Fast Fourier transform filter in the Spectra Manager software. The resulting ellipticities were normalized to concentration and number of amino acids by Equation 4,

|

where θ is the ellipticity in degrees, MW is the molecular weight in g/mol, C is the concentration of oxidized cVIMP-Cys in g/ml, l is the path length in cm, and N is the number of amino acids in the sequence. [θ]MRW is short for the mean residue molar ellipticity.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR samples were in 50 mm Na-phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.0, and 10% D2O, 1% NaN3, and 1% 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS). For the backbone assignment, spectra of the reduced form of 15N,13C-labeled cVIMP-Cys (265 μm) were recorded in the presence of 10 mm TCEP, while spectra of the oxidized form of 15N,13C-labeled cVIMP-Cys (291 μm) were recorded in the presence of 5 mm GSSG. All NMR experiments were performed at 5 °C on Varian Inova 750 MHz and 800 MHz spectrometers. For sequential assignment of reduced cVIMP-Cys Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC), HNCO, HNCA, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, and HNN spectra were recorded. Assignment of oxidized cVIMP-Cys was based on the assignment of the reduced form and HNCA, HNCO, and HNN spectra. All pulse sequences were from Varian Biopack. All spectra were referenced to DSS, processed in nmrPipe (33), and analyzed with CCPNMR Analysis (34). HSQC spectra were recorded before and after each data acquisition to check the redox state and potential degradation of each sample. The chemical shift assignments of oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys have been deposited in BioMagResBank (BMRB) with the accession number 18176 and 18177, respectively.

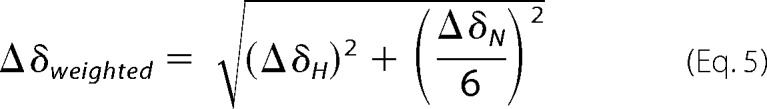

HSQC spectra of 15N-cVIMP-Cys (50 μm) with unlabeled p97N (60 μm or 173 μm) and without p97N were recorded in the presence of 10 mm TCEP. The spectra were assigned based on the assignment of the reduced form. The intensity ratio of each peak was calculated from the height of the peak of cVIMP-Cys in complex with p97N (Icplx) divided by the height of the peak of cVIMP-Cys without p97N (Iapo). The weighted chemical shift difference (Δδweighted) between cVIMP-Cys in complex with p97N and without p97N was calculated by Equation 5,

|

where ΔδH and ΔδN are the changes in 1H and 15N chemical shifts when p97N is added.

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of cVIMP-Cys

To analyze redox and structural properties of VIMP we chose to work with a fragment comprising the entire cytosolic region of the protein, i.e. residues 49–189 (Fig. 1A). In this construct, termed cVIMP-Cys, we added to the wild-type sequence an initiator Met and replaced the endogenous Sec at position 188 with a Cys residue. This was done due to the relatively low expression level of the Sec-containing construct (cVIMP-Sec). The low expression level was observed despite the use of a system optimized for expression of human selenoproteins in E. coli that is designed to ensure the highest possible level of Sec incorporation (data not shown) (35). On the contrary, we observed good expression of cVIMP-Cys upon induction with IPTG (Fig. 1B). Given the high pI of 10.0 for cVIMP-Cys, we used cation-exchange chromatography as a first purification step. When followed by size-exclusion chromatography we obtained pure cVIMP-Cys in a yield of ∼3 mg/liter of culture medium (Fig. 1B). The identity of the purified protein was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. A mass of 15754.0 Da for oxidized cVIMP-Cys was obtained, in agreement with the predicted mass of 15753.9 Da (data not shown).

Cys-174 and Cys-188 Form a Disulfide in cVIMP-Cys

With the exception of SelP, human selenoproteins all contain a single Sec residue (20, 23). This residue provides redox activity as a consequence of the high nucleophilicity (20, 23). In the cytosolic domain of human VIMP, the only Cys present is found in position 174 (Fig. 1A). We reasoned that this Cys could potentially function to resolve mixed selenosulfide bridges between VIMP and its substrates, akin to the second Cys of the active site Cys-Xaa-Xaa-Cys motif in thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases (36). If so, Cys-174 should be able to form a disulfide with Cys-188 in cVIMP-Cys. This idea was tested in the experiments shown in Fig. 2, A and B. First, we investigated the mobility of purified cVIMP-Cys by non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE. A small but discernable mobility shift was observed with the oxidized form of the protein migrating faster than the reduced form (Fig. 2A).

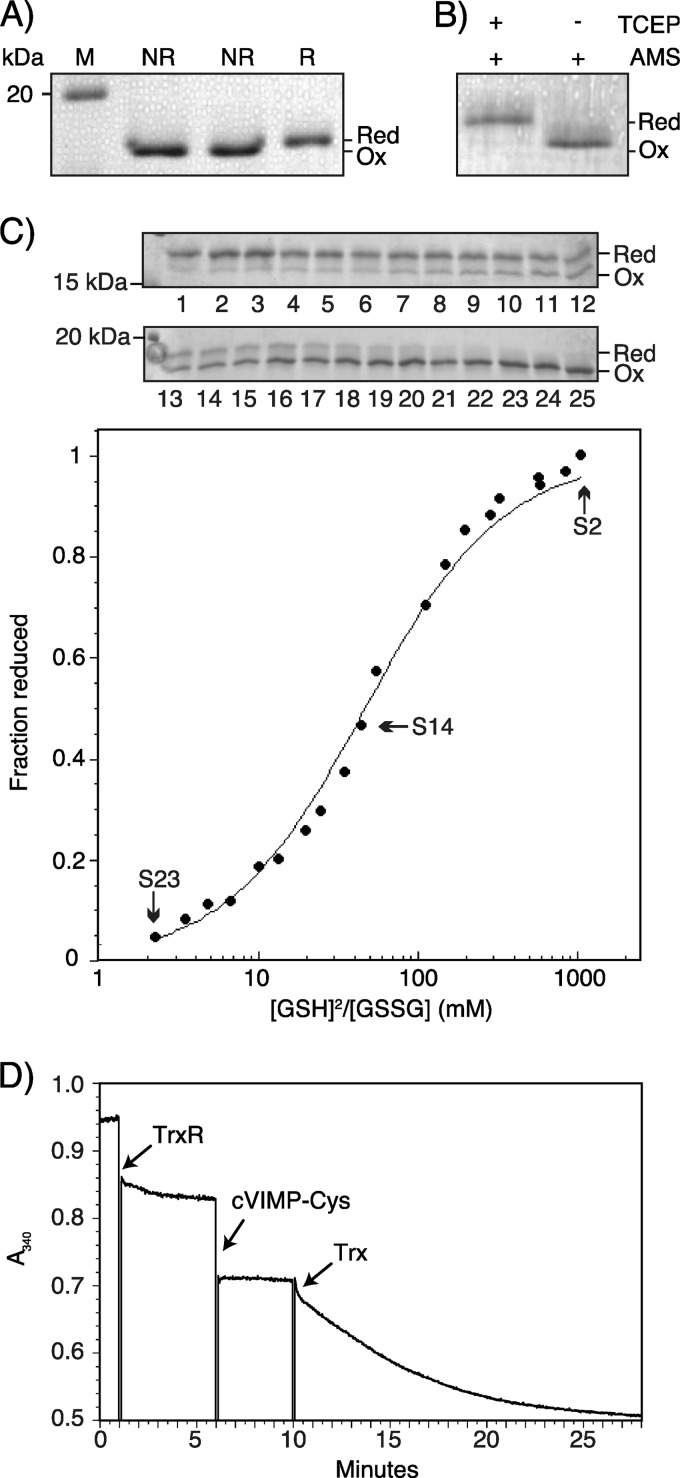

FIGURE 2.

Redox characterization of cVIMP-Cys. A, 15% Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of cVIMP-Cys under non-reducing (NR; the exact same sample loaded twice) and reducing (R; 10 mm DTT) conditions, as indicated above each lane. M denotes molecular weight marker. Note that the mobility shift observed for the reduced protein was also seen for a small fraction of the molecules in the non-reducing samples bordering the reducing samples as a result of the diffusion of the reducing agent into the neighboring lane. B, purified cVIMP-Cys was incubated either with or without 10 mm TCEP and subsequently modified with AMS. The position of oxidized (Ox) and reduced (Red) cVIMP-Cys is marked on each gel. C, equilibrium constant for the reaction between cVIMP-Cys and glutathione. 18% non-reducing Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels of AMS-modified cVIMP-Cys incubated at different ratios of [GSH]2/[GSSG] (samples 2–23). The position of reduced (Red) and oxidized (Ox) cVIMP-Cys is marked. The intensity of each band was quantified using the ImageJ software and plotted as fraction reduced cVIMP-Cys versus [GSH]2/[GSSG], which was determined by HPLC analysis. Sample 1 (reduced with 0.5 mm TCEP), sample 24 (oxidized with 2 mm GSSG), and sample 25 (untreated) were not included in the plot. Neither was sample 6 (an outlier) nor sample 12 (not possible to quantify from the gel). Data points for samples 2, 14 and 23 are indicated. The following equation: Fraction of reduced cVIMP-Cys = [GSH]2/[GSSG]/(Keq + [GSH]2/[GSSG]) was used to fit to the data points, which yielded a Keq = 47 mm. D, cVIMP-Cys is reduced by the thioredoxin system in vitro. The absorbance of 155 μm NADPH was followed at 340 nm over time upon the addition of components of the thioredoxin system and purified cVIMP-Cys. The arrows indicate the time points where TrxR (0.1 μm), cVIMP-Cys (25 μm), and Trx (0.5 μm) were added.

As a prerequisite for determining the reduction potential of cVIMP-Cys based on the mobility difference between the oxidized and reduced forms (see below), we next used chemical modification of free cysteines with the alkylating agent AMS to exaggerate the mobility shift described above. Because modification with AMS adds 537 Da per cysteine, this procedure provides, as a result of the retarded mobility due to the addition of two molecules of AMS, a direct visualization of the fraction of molecules present in the reduced state in the sample. When pretreating the protein with the reducing agent TCEP before adding AMS, we observed the expected mobility shift (Fig. 2B). Purified cVIMP-Cys that had not been preincubated with TCEP did not shift upon AMS treatment. We concluded that the Cys174-Cys188 disulfide bond forms in the entire population of cVIMP-Cys molecules, a finding that suggests that a Cys174-Sec188 selenosulfide bond forms in the native sequence.

Reduction Potential Determination for cVIMP-Cys

The lack of purified cVIMP-Sec prevented the determination of the reduction potential for the presumed Cys174-Sec188 selenosulfide bond. Instead, we established the reduction potential for Cys174-Cys188 in cVIMP-Cys to provide an indication of the stability of the selenosulfide bond in the wild-type sequence. A priori, the method of choice for these studies was fluorescence spectroscopy, which we have previously used to determine the reduction potential for certain ER oxidoreductases (37, 38). However, we observed no significant difference between oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys by this method (data not shown). Instead, we used the AMS shift assay described above and quantified the fraction of reduced cVIMP-Cys from the intensities of the two bands representing oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys in Coomassie-stained gels. Although this method is unlikely to be as accurate as fluorescence spectroscopy, we nonetheless obtained reproducible results from three independent experiments. In the experimental procedure used, cVIMP-Cys was allowed to equilibrate in redox buffers of different GSH/GSSG ratios under the exclusion of oxygen. At the end of the incubation period, thiol-disulfide exchange was quenched by the addition of TCA, which at the same time precipitated the protein. After redissolving the pellet under denaturing conditions in a buffer containing AMS for modification of free cysteines, samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The fraction of reduced cVIMP-Cys was then plotted against experimental values for [GSH]2/[GSSG], as determined by HPLC analysis (see “Experimental Procedures”). This was done because we consistently observed that the experimentally determined [GSH]2/[GSSG] values were lower than the calculated theoretical values despite precautions to avoid air oxidation in our experiments. A prominent cause for the observed difference could thus well be oxidation of the GSH powder.

After fitting Equation 1 to the experimental data (Fig. 2C), the method gave an equilibrium constant for cVIMP-Cys and glutathione of Keq = 47 mm. Applying the Nernst equation and the standard reduction potential of −240 mV at pH 7.0 and 25 °C for glutathione, this corresponds to a reduction potential of −200 mV for cVIMP-Cys. Based on comparative studies performed on other proteins, the reduction potential for cVIMP-Sec would expectedly be lower than the value obtained here for cVIMP-Cys (see “Discussion”).

Oxidized cVIMP-Cys Is a Good Substrate of the Thioredoxin System in Vitro

In the cell, the stable selenosulfide in VIMP would require reduction to regenerate the reduced state of the active site. We therefore tested the ability of the cytosolic thioredoxin (Trx) system to reduce cVIMP-Cys. In this system, NADPH functions as the electron donor to reduce thioredoxin reductase (TrxR). This enzyme in turn reduces the thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase thioredoxin, which then reduces the substrate (39).

We chose to use the well-established spectrophotometric assay for the reduction of protein disulfides by Trx (40). Here, the absorbance of NADPH at 340 nm is followed upon the addition of each component of the Trx system as well as the substrate. A decrease in absorbance indicates NADPH oxidation and thus substrate reduction. Initially, 155 μm of NADPH and 0.1 μm TrxR were added to the cuvette and incubated for 5 min (Fig. 2D). Next, 25 μm oxidized cVIMP-Cys was added. This gave no change in absorbance (apart from the effect of dilution), and thus TrxR was not able to reduce cVIMP-Cys directly. Addition of 0.5 μm Trx on the other hand resulted in rapid consumption of NADPH, indicating reduction of cVIMP-Cys via Trx. As a control, addition of Trx prior to cVIMP-Cys had no effect on absorbance levels (data not shown), demonstrating that the observed decrease was dependent on cVIMP-Cys. For comparison, we investigated the reduction of human insulin and GSSG, both known substrates of Trx (40). Compared with the rate of cVIMP-Cys reduction, the three disulfides in human insulin were reduced much slower, while the rate of GSSG reduction was even slower than observed for insulin (data not shown).

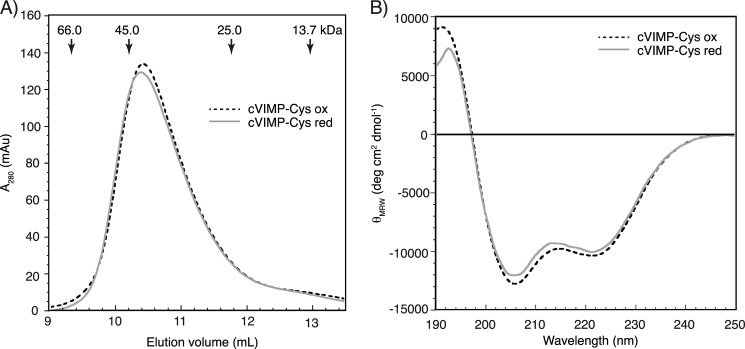

Analytical Gel Filtration Reveals a Large Apparent Molecular Mass of cVIMP-Cys

Next we wanted to investigate structural properties and potential overall structural differences between the two redox forms of cVIMP-Cys. As a first method to do so, we performed analytical gel filtration on the oxidized and reduced protein. No significant difference was observed when comparing the elution volume of the two redox forms (Fig. 3A). The similarity in the hydrodynamic properties indicated that the overall structure did not change with the redox state. When comparing the elution volume of cVIMP-Cys to globular standard proteins, the VIMP construct was found to have an apparent molecular mass of ∼42 kDa (Fig. 3A). Compared with the calculated mass of 15.8 kDa for monomeric cVIMP-Cys the surprisingly large observed apparent molecular mass indicated a non-spherical shape of cVIMP-Cys and/or the formation of oligomers, most likely dimers or trimers.

FIGURE 3.

Basic structural characterization of oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys. A, elution profiles of oxidized (dashed line) and reduced (solid line) cVIMP-Cys obtained from analytical gel filtration on a Superdex 75 column. The apparent mass of cVIMP-Cys was calculated (yielding 41.3 kDa and 42.0 kDa for oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys, respectively) from the elution volumes of standard proteins (indicated by arrows). mAU, milli absorbance units. B, Far-UV CD spectra of oxidized (dashed line) and reduced (solid line) cVIMP-Cys recorded at 5 °C. The complete reduction and oxidation of cVIMP-Cys in all experiments in this figure was verified by the AMS shift assay (data not shown).

CD Spectroscopy Displays α-Helical and Random Coil Structure

To gain further insight into the structural properties of cVIMP-Cys we used far-UV CD spectroscopy. With two distinct minima at 205 nm and 222 nm, the spectrum clearly displayed α-helical character (Fig. 3B). However, compared with the spectrum of an all α-helical protein where the peak at 222 nm is generally the most pronounced and the second band of negative ellipticity is found at 208 nm, it was clear that the cVIMP-Cys spectrum also displayed features characteristic of disordered regions. No significant change in the secondary structure content was observed between the two redox forms.

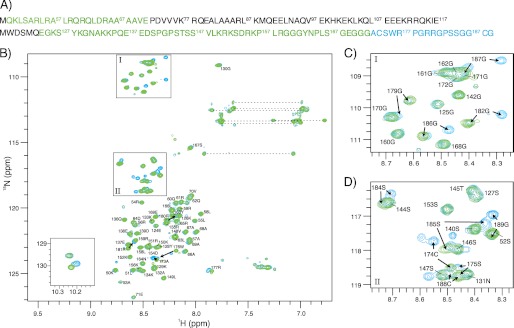

NMR Spectroscopy Indicates that cVIMP-Cys Is Partially Disordered

We next turned to NMR spectroscopy, which allowed us to gain information about redox-dependent conformational changes and structural features in cVIMP-Cys at the single residue level. We assigned HN, NH, Cα, and C′ chemical shifts for residues 49–71 and 124–189 in reduced and oxidized cVIMP-Cys. For reduced cVIMP-Cys we also assigned Cβ chemical shifts. The assignments of the peaks in the 1H,15N-HSQC spectrum are shown in Fig. 4. Ten peaks that were identified as not originating from side-chains could not be assigned. We did not observe any peaks from residues 72–123 suggesting that this stretch of the protein has non-optimal properties for NMR (see “Discussion”). From the poor dispersion particularly in the 1H dimension of the HSQC spectra in Fig. 4, it can be concluded that the assigned regions of cVIMP-Cys in both the reduced and oxidized states have very little structure. It is also evident by comparing the HSQC spectra of reduced and oxidized cVIMP-Cys that reduction of the disulfide has only little effect on the overall structure of the protein. However, residues 173–189 shifted significantly, indicating a local structural rearrangement in the C-terminal segment of the protein that contains the two Cys residues. In addition to the shifts observed for these backbone amides, one of the two peaks from the Hϵ1 and Nϵ1 side chain nuclei of Trp-119 and Trp-176 (Fig. 4B, inset), most likely the one belonging to Trp-176, also shifted its position between the two redox forms.

FIGURE 4.

HSQC spectra of oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys with assigned peaks. A, amino acid sequence of cVIMP-Cys. Black letters indicate residues that could not be assigned. For the assigned residues, blue and green letters indicate those that do and do not shift between the two redox states, respectively. B, HSQC spectrum of oxidized (blue) overlaid with the spectrum of reduced (green) cVIMP-Cys. The spectra were recorded on an 800 MHz spectrometer at 5 °C and pH 7.0. Assigned residues are marked with residue number and one letter code. Arrows indicate where the peaks shift. The isotope-dimension is marked on the axes. Boxes indicate zoom area I and II shown in C and D. Dashed lines indicate the pairwise arrangement of NH2-containing side chains from Asn and Gln. Inset: signals from the two Trp side chains. C and D, zoom of areas I and II. The assigned peaks are indicated with residue number and one letter code. Arrows indicate where the peak shifts to between the two redox states. Note that the spectrum of the oxidized sample contains peaks corresponding to both oxidized and reduced cVIMP-Cys, illustrating that the sample contained a mixture of the two redox forms (see for instance Gly-182 or Gly-186, panel C). The reason for this observation is currently unknown, but does not change the conclusions drawn based on these experiments.

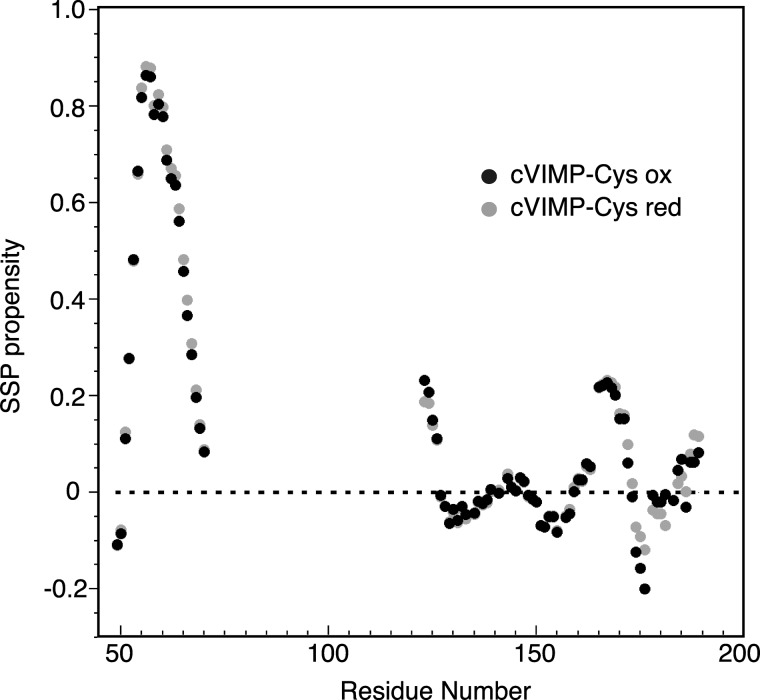

Secondary Structure Propensity Analysis

While our NMR analysis of cVIMP-Cys did not include side chain assignments or the recording of NOE spectra necessary for structure determination, it still allowed us to extract useful information about the secondary structure of the protein. For this purpose we used secondary structure propensity (SSP) analysis (41). This method combines chemical shifts from different nuclei into a single score representing the expected fraction of α-helix or β-strand for each residue. The score is calculated relative to an average chemical shift of nuclei in known α-helix or β-strand structures, and ranges between 1 or −1 for the two types of secondary structure, respectively. Here, we used the chemical shifts obtained for the Cα, C′, N, and HN nuclei in cVIMP-Cys to calculate secondary structure propensities (Fig. 5). It should be noted that for reduced cVIMP-Cys, for which Cβ chemical shifts were also assigned, the inclusion of these had only a minimal effect on the SSP values. The analysis clearly indicated residues ∼51–69 to constitute an α-helix. For the C-terminal half of cVIMP-Cys, values close to zero were observed indicating disordered structure. However, a short glycine-rich stretch involving residues ∼160–172 showed a small peak with values of up to 0.23, which could indicate transient formation of a non-random structure in this region. Apart from a small difference for three residues centered on Ser-175, the SPP values did not differ considerably between the two redox states of cVIMP-Cys.

FIGURE 5.

Prediction of secondary structure using chemical shifts. A, SSP analysis of α-helix (SSP score > 0) and β-strand (SSP score < 0) from Cα, C′, H, and N chemical shifts of oxidized (black dots) and reduced (gray dots) cVIMP-Cys plotted as a function of residue number. The dashed line at zero indicates disordered structure.

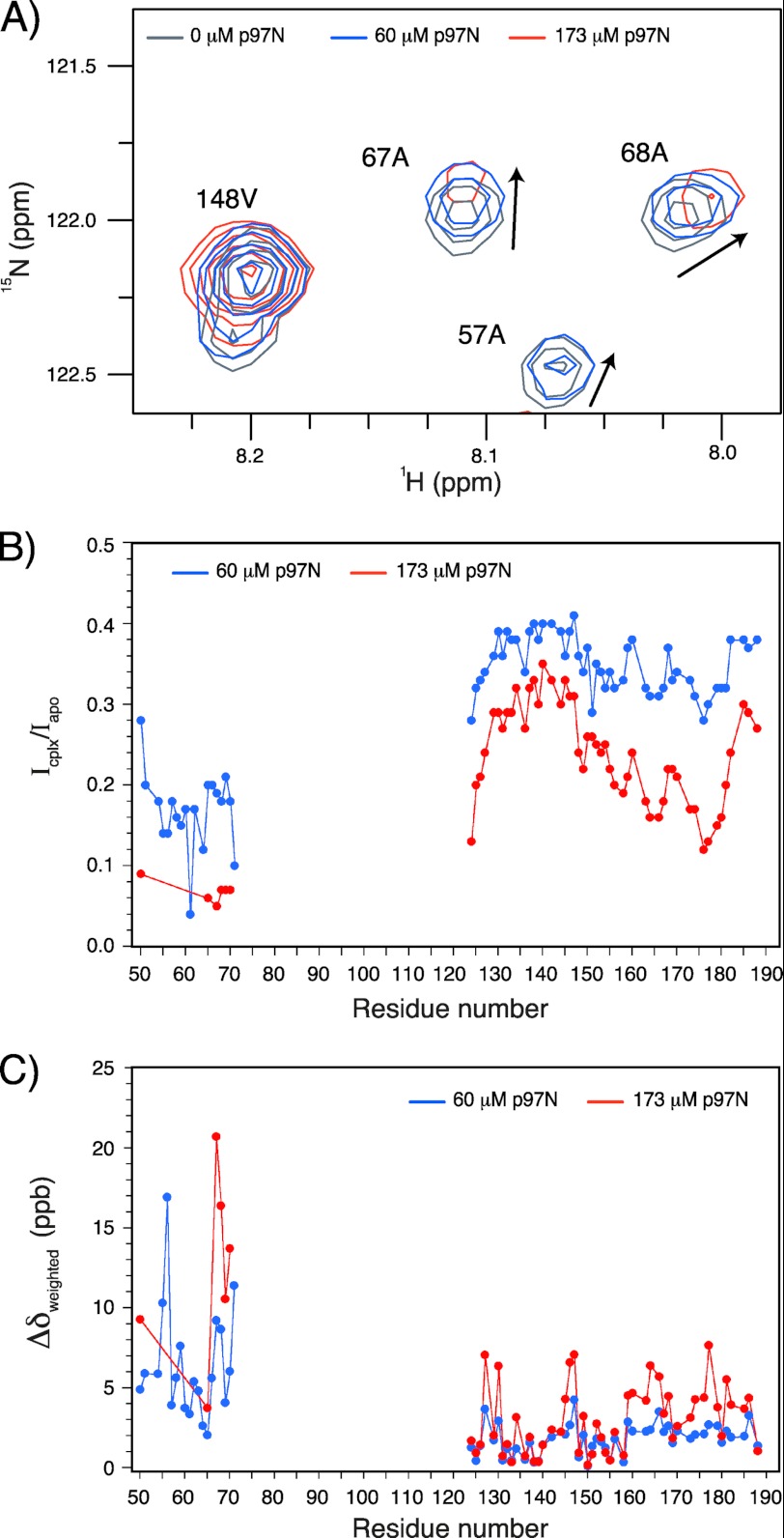

VIMP Binds p97N with Only Minor Effects in the Disordered C Terminus

The redox function of Sec indicates that orthologs of selenoproteins containing a Cys in place of the Sec also serve a function as thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases (42). Identification of such Cys/Sec pairs in homologous proteins has recently been used to uncover new thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases by data base mining (42). To identify potential Cys-containing orthologs of VIMP and thus gain further insight into this family of proteins, we performed a multiple sequence alignment for VIMP from a wide range of species (supplemental Fig. S1). The alignment identified three distinct subgroups (I-III) of VIMP proteins defined by sequence differences relating to the proposed redox-active residues. The proteins in subgroup III indeed contain a Cys in place of the Sec (see supplemental data for a more detailed discussion of the alignment).

Recently, a sequence motif with the approximate consensus R-X5-A-A-X2-R (where x denotes any residue) has been defined as the core of a p97-binding motif called a VIM (for VCP-interacting motif) (43–45). The VIM region has a highly predicted propensity for α-helix, and has experimentally been demonstrated to be helical in complex with p97 (44, 45). In human VIMP, this minimal VIM covers residues 78–88 (supplemental Fig. S1). Based on sequence conservation, the VIM in VIMP might well comprise additional important residues such as an arginine directly following the two alanines, and a Met/Leu-Gln-Glu motif directly following the last arginine of the minimal VIM (supplemental Fig. S1). In the alignment, the region around the VIM is the best conserved.

In the context of the current data, we wanted to investigate whether the binding of VIMP to p97 would, in addition to the VIM, involve the disordered C-terminal region. Previously, it has been demonstrated that VIMP does not bind to p97 devoid of the so-called N-domain (22). Moreover, the N-domain has been shown to bind directly to the VIM of different proteins via a central cleft between two subdomains (44, 45).

Titration of 15N-labeled cVIMP-Cys with the N-domain of (p97N) resulted in sequence-specific and concentration-dependent changes in the 1H,15N HSQC spectra (Fig. 6A), demonstrating an interaction between the two proteins. Specifically, the peaks from residues 50–71 of cVIMP-Cys (50 μm) showed significant line broadening, which resulted in an ∼85% decrease in signal intensity at 60 μm p97N and complete loss of several signals at 173 μm p97N (Fig. 6B). In addition, small yet distinct changes in chemical shifts occurred (Fig. 6C). These spectral changes clearly show that the environment of residues 50–71, quite closely corresponding to the predicted helix (Fig. 5), changed upon the formation of a VIMP-p97N complex, either as a result of an interaction between these residues and p97N or caused by long-range structural changes in VIMP induced by p97N. The VIM region of cVIMP-Cys is located in the segment of the protein that was not observed in the 1H,15N HSQC. Consequently, based on these data we cannot verify that p97 interacts with this particular motif, although we find it highly likely based on all available information.

FIGURE 6.

cVIMP-Cys interacts with the N-domain of p97. A, HSQC spectra were recorded of 15N-cVIMP-Cys (50 μm) in the absence of p97N, and in the presence of 60 μm and 173 μm p97N. Four selected peaks from the HSQC spectra are shown as an overlay of 50 μm 15N-cVIMP-Cys (gray), 50 μm 15N-cVIMP-Cys with 60 μm p97N (blue, 4-fold decrease in the base contour level), and 50 μm 15N-cVIMP-Cys with 173 μm p97N (red, 8-fold decrease in the base contour level). The plotting at different contour levels of the spectra is necessary to see peaks in all three spectra. Arrows indicate the direction of the chemical shift change. B, plot of intensity ratio (Icplx/Iapo) as a function of residue number. Icplx denotes the intensity of peaks in the sample with either 60 μm p97N (blue) or 173 μm (red) p97N, and Iapo refers to the intensity of peaks in the sample without p97N. C, change in peak positions reported as the weighted chemical shift difference induced by addition of p97N (Δδweighted) is plotted as a function of residue number for peaks in the samples with 60 μm p97N (blue) and 173 μm p97N (red). Δδweighted is given in parts per billion (ppb). Peaks that were poorly defined or completely absent are not included in the plots in panels B and C (thus the lack of data points for e.g. most of residues 50–71 in the sample with 173 μm p97N). Signals for residues 72–123 were not observed even in the absence of p97N (see text for details).

The unstructured C-terminal part of cVIMP-Cys was less affected by the binding of p97N than the N-terminal part. Only a few residues in the C-terminal part of cVIMP-Cys showed significant changes in chemical shifts (Fig. 6C). In contrast, sequence-dependent line broadening was observed, although the effect was much smaller than in the N-terminal region of cVIMP-Cys (Fig. 6B). Residues ∼163–181 were broadened the most, which suggested the formation of some transient structure between this region of cVIMP-Cys and the N-domain of p97. However, the data gave no indication for the formation of a compact stable structure in the C-terminal region of cVIMP-Cys upon binding of p97N.

DISCUSSION

The current study reveals fundamental redox and structural properties of human VIMP. In cVIMP-Cys we identified a disulfide bond between Cys-174 and Cys-188 with a reduction potential of −200 mV. This indicates the presence of a stable selenosulfide in VIMP, as selenosulfides are thermodynamically much more stable than the corresponding disulfides (46–48). VIMP therefore likely functions as a reductase, the common redox function of selenoproteins. Selenoprotein enzymes often catalyze the reduction of disulfides, but also function as e.g. glutathione peroxidases and methionine-R-sulfoxide reductases. However, VIMP does not contain the specific sequence characteristics of these two classes of enzymes. We therefore find it most likely that the protein catalyzes disulfide-bond reduction.

During the process of reduction, a mixed selenosulfide will be formed with the substrate. This bond would then be resolved by Cys-174 to form the Cys174-Sec188 selenosulfide, which must be reduced for the enzyme to function in another round of substrate reduction. The TrxR/Trx and glutathione reductase/glutaredoxin systems comprise the two cellular pathways for reduction of proteins in the cytosol (49). Here, we have shown that VIMP is a good substrate for the Trx system in vitro. While not ruling out a role of the glutathione system, the data point to the thioredoxin system as a prime candidate for further cellular studies.

Several selenoproteins such as thioredoxin reductase and methionine-R-sulfoxide reductases have orthologs containing a Cys in place of the Sec (see e.g. (50, 51)). Studies on such proteins have shown that efficient catalysis is not dependent on the Sec, and that each type of ortholog has evolved specific characteristics of the active-site sequence to optimize activity. The VIMP proteins in subgroup III (see supplemental Fig. S1) provide another example of such orthologs where the active site Sec has been replaced by a Cys.

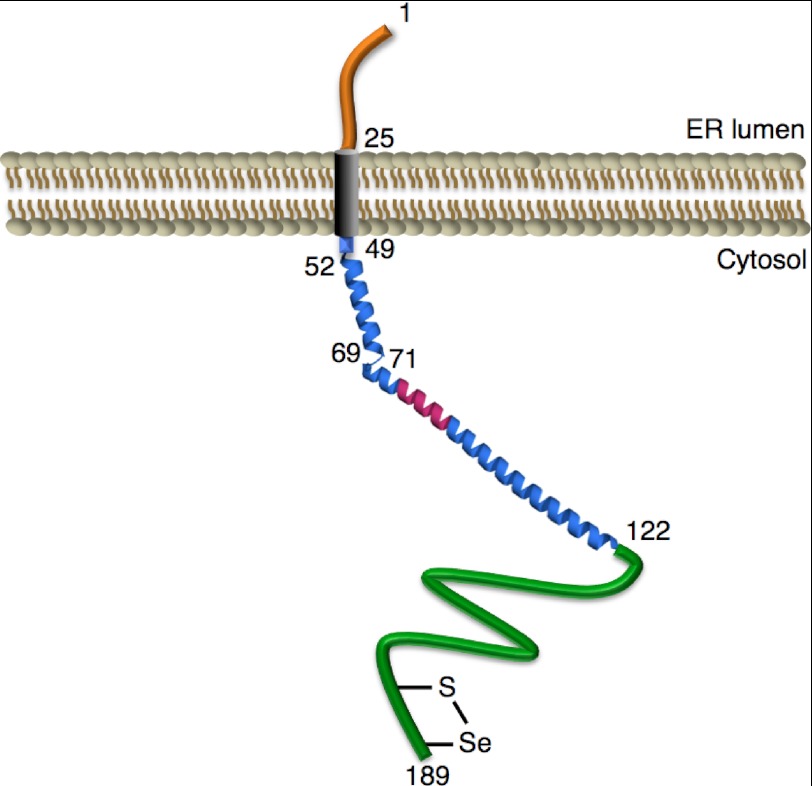

The SSP analysis predicted secondary structural properties for cVIMP-Cys with the exception of residues 72–123, which were not detected in the NMR spectra (Fig. 5). However, the Protein Data Bank contains an entry for a crystal structure for the fragment of human VIMP comprising residues 52–122 (PDB ID: 2Q2F). This structure is unpublished and has therefore not been subjected to peer review. Still, it strongly corroborates our findings from the CD and NMR analyses (see below). The fragment shows an elongated structure with two α-helices constituting residues 52–69 and 71–122, respectively. Based on this structure and the current data we propose an overall structural model of VIMP where the transmembrane region is followed almost directly by the extended α-helical structure, which is in turn followed by an intrinsically disordered region (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

An overall structural model for VIMP. The ER (orange) and transmembrane regions (gray) are based on predictions using TMHMM (21, 22). The overall structure of the cytosolic region is based on findings in this study, as well as the crystal structure of a VIMP fragment comprising residues 52–122 (PDB ID: 2Q2F; unpublished). This cytosolic region consists of an α-helical region (blue) harboring the putative VIM (residues 78–88; pink), and an intrinsically disordered region (residues 123–189; green). The expected selenosulfide bond formed by Cys-174 and Sec188 is indicated. Numbers denote residue positions.

The notion that cVIMP-Cys is extended rather than being globular with a classical hydrophobic core is supported by fluorescence spectroscopy, which showed an emission maximum at 356 nm (data not shown), a value typically observed for solvent-exposed Trp residues. In the α-helical crystal structure, the first helix closely matches the predictions of the SSP analysis. The second long helix could well be stabilized by dimer formation since residues 80–120 are strongly predicted by the PairCoil2 (52) and MultiCoil (53) algorithms to form a dimeric coiled coil, as also recently noted elsewhere (25). Moreover, the backbone amides of this long helix could not be detected by NMR spectroscopy. This observation clearly demonstrates that residues 72–123 adopt some structure. The reason that no NMR signals are observed could be: (i) that the putative coiled-coil region has very slow rotational diffusion, or (ii) that the coiled-coil region engages in a conformational exchange process (e.g. monomer-dimer equilibrium) on the milli-second time scale. Both scenarios would result in fast transverse relaxation and consequently signals with very low intensities.

In the HSQC spectra, dilution of VIMP from 265 μm to 32.5 μm did not result in any change (data not shown). A change would have been expected if exchange between monomeric and dimeric VIMP were the reason for the missing peaks at 265 μm. If slow tumbling was causing the missing peaks it would be expected that increasing the temperature, which also increases the tumbling rate, would give sharper peaks and that more peaks would appear. In contrast, we observed fewer peaks when increasing the temperature (data not shown). It is thus likely that the reason for the missing peaks is some conformational exchange process other than a monomer-dimer equilibrium.

The C-terminal half of cVIMP-Cys, residues 123–189, showed clear indications by a number of the applied techniques to be intrinsically disordered. The same conclusion was reached using various predictors of disorder (data not shown). Generally, intrinsically disordered proteins contain highly dynamic polypeptide segments devoid of a well-defined tertiary structure (54). The capacity to take on a multitude of conformations allows these proteins to interact with a variety of partners, as seen for e.g. chaperones that must be able to recognize the numerous conformations that characterize misfolded proteins (55). Similarly, VIMP should be able to interact with a wide variety of ERAD substrates, which are (partly) unfolded as they emerge from the dislocon where they are expectedly presented to VIMP by p97.

It is interesting to note that the C-terminal region encompassing Tyr163-Gly189 is well conserved irrespective of the sequence subgroup to which it belongs (supplemental Fig. S1), and despite the observation that intrinsically disordered regions are typically not well conserved throughout evolution (56, 57). We thus speculate that residues 163–189 support the interaction with a cellular redox regulator (e.g. thioredoxin) and contain substrate recognition elements. Indeed, the observed effect of p97 binding on residues 163–181 (Fig. 6B) could reflect the capability of this region for protein-protein interaction. The conformational plasticity offered by residues ∼123–162 would then provide adaptability for interacting with substrates of different shapes. A similar mode of operation has been observed for the E3 ligase from yeast, San1, where conserved regions of around 20 residues are responsible for substrate binding, while intervening regions of disorder were proposed to provide flexibility for binding a variety of substrates (58).

Though other redox functions are possible, the redox properties of VIMP would presumably allow it to reduce particularly stable disulfides in ERAD substrates that were not reduced prior to retrotranslocation. Such stable disulfides could for instance be present in small compact domains formed in large multidomain proteins prior to misfolding of other regions of the molecule. Ongoing experiments are directed at investigating these ideas in detail.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Hartmann-Petersen for helpful suggestions, E. Arnér (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm) for valuable advice on setting up the NADPH/TrxR/Trx assay, K. S. Jensen for initial help on the project, H. Meyer for providing the p97N expression plasmid, Z. Nikrozi for technical assistance, and all members of the Ellgaard laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research (Natural Sciences), Novo Nordisk Fonden, Lundbeckfonden, and the Alfred Benzon Foundation.

Data deposition: Backbone chemical shifts have been deposited at the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank with accession numbers: 18176 (oxidized cVIMP-Cys); 18177 (reduced cVIMP-Cys).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- Amp

- ampicillin

- AMS

- 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid

- ERAD

- endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- GSH

- reduced glutathione

- GSSG

- oxidized glutathione

- HSQC

- Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence

- IPTG

- isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- LB

- Luria Broth

- NMR

- nuclear magnetic resonance

- PMSF

- phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- redox

- reduction-oxidation

- Sec

- selenocysteine

- SelS

- selenoprotein S

- SSP

- secondary structure propensity

- TCA

- trichloroacetic acid

- TCEP

- Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- Trx

- thioredoxin

- TrxR

- thioredoxin reductase

- VIM

- VCP-interacting motif

- VIMP

- VCP-interacting membrane protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smith M. H., Ploegh H. L., Weissman J. S. (2011) Road to ruin: targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 334, 1086–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Claessen J. H., Kundrat L., Ploegh H. L. (2012) Protein quality control in the ER: balancing the ubiquitin checkbook. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 22–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carvalho P., Goder V., Rapoport T. A. (2006) Distinct ubiquitin-ligase complexes define convergent pathways for the degradation of ER proteins. Cell 126, 361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Denic V., Quan E. M., Weissman J. S. (2006) A luminal surveillance complex that selects misfolded glycoproteins for ER-associated degradation. Cell 126, 349–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christianson J. C., Shaler T. A., Tyler R. E., Kopito R. R. (2008) OS-9 and GRP94 deliver mutant α1-antitrypsin to the Hrd1-SEL1L ubiquitin ligase complex for ERAD. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 272–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molinari M., Calanca V., Galli C., Lucca P., Paganetti P. (2003) Role of EDEM in the release of misfolded glycoproteins from the calnexin cycle. Science 299, 1397–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oda Y., Hosokawa N., Wada I., Nagata K. (2003) EDEM as an acceptor of terminally misfolded glycoproteins released from calnexin. Science 299, 1394–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neutzner A., Neutzner M., Benischke A. S., Ryu S. W., Frank S., Youle R. J., Karbowski M. (2011) A systematic search for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane-associated RING finger proteins identifies Nixin/ZNRF4 as a regulator of calnexin stability and ER homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8633–8643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ye Y., Meyer H. H., Rapoport T. A. (2001) The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature 414, 652–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christianson J. C., Olzmann J. A., Shaler T. A., Sowa M. E., Bennett E. J., Richter C. M., Tyler R. E., Greenblatt E. J., Harper J. W., Kopito R. R. (2012) Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mancini R., Fagioli C., Fra A. M., Maggioni C., Sitia R. (2000) Degradation of unassembled soluble Ig subunits by cytosolic proteasomes: evidence that retrotranslocation and degradation are coupled events. FASEB J. 14, 769–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tortorella D., Story C. M., Huppa J. B., Wiertz E. J., Jones T. R., Bacik I., Bennink J. R., Yewdell J. W., Ploegh H. L. (1998) Dislocation of type I membrane proteins from the ER to the cytosol is sensitive to changes in redox potential. J. Cell Biol. 142, 365–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fagioli C., Mezghrani A., Sitia R. (2001) Reduction of interchain disulfide bonds precedes the dislocation of Ig-mu chains from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol for proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40962–40967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Molinari M., Galli C., Piccaluga V., Pieren M., Paganetti P. (2002) Sequential assistance of molecular chaperones and transient formation of covalent complexes during protein degradation from the ER. J. Cell Biol. 158, 247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okuda-Shimizu Y., Hendershot L. M. (2007) Characterization of an ERAD pathway for nonglycosylated BiP substrates, which require Herp. Mol. Cell 28, 544–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ushioda R., Hoseki J., Araki K., Jansen G., Thomas D. Y., Nagata K. (2008) ERdj5 is required as a disulfide reductase for degradation of misfolded proteins in the ER. Science 321, 569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hagiwara M., Maegawa K., Suzuki M., Ushioda R., Araki K., Matsumoto Y., Hoseki J., Nagata K., Inaba K. (2011) Structural basis of an ERAD pathway mediated by the ER-resident protein disulfide reductase ERdj5. Mol. Cell 41, 432–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riemer J., Appenzeller-Herzog C., Johansson L., Bodenmiller B., Hartmann-Petersen R., Ellgaard L. (2009) A luminal flavoprotein in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14831–14836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riemer J., Hansen H. G., Appenzeller-Herzog C., Johansson L., Ellgaard L. (2011) Identification of the PDI-family member ERp90 as an interaction partner of ERFAD. PLoS One 6, e17037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kryukov G. V., Castellano S., Novoselov S. V., Lobanov A. V., Zehtab O., Guigó R., Gladyshev V. N. (2003) Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science 300, 1439–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E. L. (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ye Y., Shibata Y., Yun C., Ron D., Rapoport T. A. (2004) A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature 429, 841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arnér E. S. (2010) Selenoproteins-What unique properties can arise with selenocysteine in place of cysteine? Exp. Cell Res. 316, 1296–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Röseler A., Prieto J. H., Iozef R., Hecker B., Schirmer H., Kuelzer S., Przyborski J., Rahlfs S., Becker K. (2012) Insight into the Selenoproteome of the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 534–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shchedrina V. A., Everley R. A., Zhang Y., Gygi S. P., Hatfield D. L., Gladyshev V. N. (2011) Selenoprotein K binds multiprotein complexes and is involved in the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42937–42948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lilley B. N., Ploegh H. L. (2005) Multiprotein complexes that link dislocation, ubiquitination, and extraction of misfolded proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14296–14301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isaacson R. L., Pye V. E., Simpson P., Meyer H. H., Zhang X., Freemont P. S., Matthews S. (2007) Detailed structural insights into the p97-Npl4-Ufd1 interface. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 21361–21369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker J. M., ed), pp. 571–607, Humana Press [Google Scholar]

- 29. Riddles P. W., Blakeley R. L., Zerner B. (1979) Ellman's reagent: 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)–a reexamination. Anal. Biochem. 94, 75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chau M. H., Nelson J. W. (1991) Direct measurement of the equilibrium between glutathione and dithiothreitol by high performance liquid chromatography. FEBS Lett. 291, 296–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abramoff M. D., Magelhaes P. J., Ram S. J. (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams C. H. (1992) Lipoamide Dehydrogenase, Glutathione Reductase, Thioredoxin Reductase, and Mercuric Ion Reductase—a Family of Flavoenzyme Transhydrogenases, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 33. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vranken W. F., Boucher W., Stevens T. J., Fogh R. H., Pajon A., Llinas M., Ulrich E. L., Markley J. L., Ionides J., Laue E. D. (2005) The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59, 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arnér E. S., Sarioglu H., Lottspeich F., Holmgren A., Böck A. (1999) High-level expression in Escherichia coli of selenocysteine-containing rat thioredoxin reductase utilizing gene fusions with engineered bacterial-type SECIS elements and co-expression with the selA, selB and selC genes. J. Mol. Biol. 292, 1003–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Depuydt M., Messens J., Collet J. F. (2011) How proteins form disulfide bonds. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 49–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Frickel E. M., Frei P., Bouvier M., Stafford W. F., Helenius A., Glockshuber R., Ellgaard L. (2004) ERp57 is a multifunctional thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18277–18287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haugstetter J., Blicher T., Ellgaard L. (2005) Identification and characterization of a novel thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8371–8380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arnér E. S., Holmgren A. (2000) Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 6102–6109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holmgren A. (1984) Enzymatic reduction-oxidation of protein disulfides by thioredoxin. Methods Enzymol. 107, 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marsh J. A., Singh V. K., Jia Z., Forman-Kay J. D. (2006) Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between α- and γ-synuclein: implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 15, 2795–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fomenko D. E., Gladyshev V. N. (2012) Comparative genomics of thiol oxidoreductases reveals widespread and essential functions of thiol-based redox control of cellular processes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ballar P., Shen Y., Yang H., Fang S. (2006) The role of a novel p97/valosin-containing protein-interacting motif of gp78 in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35359–35368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stapf C., Cartwright E., Bycroft M., Hofmann K., Buchberger A. (2011) The general definition of the p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP)-interacting motif (VIM) delineates a new family of p97 cofactors. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38670–38678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hänzelmann P., Schindelin H. (2011) The structural and functional basis of the p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP)-interacting motif (VIM): mutually exclusive binding of cofactors to the N-terminal domain of p97. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38679–38690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Besse D., Siedler F., Diercks T., Kessler H., Moroder L. (1997) The redox potential of selenocysteine in unconstrained cyclic peptides. Angew. Chem. 36, 883–885 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beld J., Woycechowsky K. J., Hilvert D. (2007) Selenoglutathione: efficient oxidative protein folding by a diselenide. Biochemistry 46, 5382–5390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Metanis N., Keinan E., Dawson P. E. (2006) Synthetic seleno-glutaredoxin 3 analogues are highly reducing oxidoreductases with enhanced catalytic efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16684–16691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. López-Mirabal H. R., Winther J. R. (2008) Redox characteristics of the eukaryotic cytosol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 629–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gromer S., Johansson L., Bauer H., Arscott L. D., Rauch S., Ballou D. P., Williams C. H., Jr., Schirmer R. H., Arnér E. S. (2003) Active sites of thioredoxin reductases: why selenoproteins? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12618–12623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim H. Y., Gladyshev V. N. (2005) Different catalytic mechanisms in mammalian selenocysteine- and cysteine-containing methionine-R-sulfoxide reductases. PLoS Biol. 3, e375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McDonnell A. V., Jiang T., Keating A. E., Berger B. (2006) Paircoil2: improved prediction of coiled coils from sequence. Bioinformatics 22, 356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wolf E., Kim P. S., Berger B. (1997) MultiCoil: a program for predicting two- and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 6, 1179–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dunker A. K., Oldfield C. J., Meng J., Romero P., Yang J. Y., Chen J. W., Vacic V., Obradovic Z., Uversky V. N. (2008) The unfoldomics decade: an update on intrinsically disordered proteins. BMC Genomics 9, Suppl. 2, S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rosenbaum J. C., Gardner R. G. (2011) How a disordered ubiquitin ligase maintains order in nuclear protein homeostasis. Nucleus 2, 264–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brown C. J., Takayama S., Campen A. M., Vise P., Marshall T. W., Oldfield C. J., Williams C. J., Dunker A. K. (2002) Evolutionary rate heterogeneity in proteins with long disordered regions. J. Mol. Evol. 55, 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Brown C. J., Johnson A. K., Daughdrill G. W. (2010) Comparing models of evolution for ordered and disordered proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 609–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rosenbaum J. C., Fredrickson E. K., Oeser M. L., Garrett-Engele C. M., Locke M. N., Richardson L. A., Nelson Z. W., Hetrick E. D., Milac T. I., Gottschling D. E., Gardner R. G. (2011) Disorder targets misorder in nuclear quality control degradation: a disordered ubiquitin ligase directly recognizes its misfolded substrates. Mol. Cell 41, 93–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.