Abstract

The length of the reproductive period affects the grain yield of soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr), and genetic control of the period might contribute to yield improvement. To detect genetic factor(s) controlling the reproductive period, a population of recombinant inbred lines (RILs) was developed from a cross between Japanese landrace ‘Ippon-Sangoh’ and, Japanese cultivar ‘Fukuyutaka’ which differ in their duration from flowering to maturation (DFM) relative to the difference in the duration from sowing to flowering (DSF). In the RIL population, the DFM correlated poorly (r = −0.16 to 0.34) with the DSF in all field trials over 3 years. Two stable QTLs for the DFM on chromosomes (Chr-) 10 and 11 as well as two stable QTLs for the DSF on Chr-10 and -16 were identified. The QTL on Chr-11 for the reproductive period (designated as qDfm1; quantitative trait locus for duration from flowering to maturation 1) affected all three trials, and the difference in the DFM between the Fukuyutaka and Ippon-Sangoh was mainly accounted for qDfm1, in which the Fukuyutaka allele promoted a longer period. qDfm1 affected predominantly the reproductive period, and thus it might be possible to alter the period with little influence on the vegetative period.

Keywords: post-flowering period, SSR, yield

Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr) is a short-day crop and its life cycle is largely determined by variety-specific daylength requirements for the initiation of floral development. The life span of each variety is a principal factor for yield potential in different regions, because the suitable season for soybean production is dependent on latitude, temperature, and other environmental factors (Heatherly and Elmore 2004). Genetic factors controlling the developmental phases, such as flowering and maturation, have been comprehensively investigated in soybean, and several qualitative trait loci have been identified as a series E loci; E1 and E2 (Bernard 1971), E3 (Buzzell 1971), E4 (Buzzell and Voldeng 1980), E5 (McBlain and Bernard 1987), E6 (Bonato and Vello 1999), E7 (Cober and Voldeng 2001) and E8 (Cober et al. 2010). Most of these have been identified as factors affecting the flowering time, as hereafter defined as DSF; duration from sowing to flowering (R1 stage described by Fehr et al. [1977]), or growing period from sowing to R8 stage (DSM; duration from sowing to maturation), and the effect of each locus has been confirmed in further genetic analyses, except for E6 and E7. The effects of E1 to E5 on DSF and DSM have been assessed in near-isogenic lines developed by recurrent backcrossing (Cober et al. 1996, 2001, McBlain et al. 1987, Messina et al. 2006, Saindon et al. 1989), and these studies confirmed that the dominant alleles of these loci prolong DSM as well as DSF in response to photoperiod. The effect of E8 on DSM was also confirmed using near-isogenic lines (Cober et al. 2010). In addition, it has been revealed that most of the E series genes affect the reproductive period (post-flowering period) as well as DSF and DSM. It was reported that the dominant alleles of E2 to E4 prolonged the reproductive period from stage R1 to R8 (DFM; duration from flowering to maturation) with different degrees (McBlain et al. 1987, Saindon et al. 1989). Kumudini et al. (2007) investigated the duration from stage R1 to R5 of near-isogenic lines of E1 to E4 and E7 under different day-length conditions, and estimated that the E series genes play a key role in photoperiod mediated control of the duration, though the respective effect of each gene was not clarified. Summarizing these studies, E loci seem to determine DSM through the regulation both of DFM and DSF.

On the other hand, the length of the post-flowering period has been considered to affect grain yield. The artificial long photoperiod exposed after stage R3 extended post-flowering periods among the varieties tested (Kantolic and Slafer 2001), and the pod and seed number, and eventually grain yield increased in accordance with the extended period (Kantolic and Slafer 2001, 2005). Appropriate control of the balance between pre- and post-flowering periods may result in higher yield potential (Kantolic and Slafer 2001). A novel genetic factor that affects only or mainly DFM is requisite to assess this hypothesis, but the well-studied E loci alter both DSF and DFM, and thus could not control DFM separated from DSF. Genetic analyses focused on the post-flowering period have been conducted and revealed the existence of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) that govern DFM (Cheng et al. 2011, Keim et al. 1990, Matsui et al. 2005, Orf et al. 1999, Watanabe et al. 2004). However, most QTLs affected DSF as well as DFM. Further investigations focusing on DFM are required for a better understanding of genetic control of the developmental phases and for an attempt to improve the yield through the optimization of this genetic control in breeding programs.

In this study, a population of recombinant inbred lines (RILs) was developed from a cross between two Japanese varieties; a landrace ‘Ippon-Sangoh’ and an elite variety ‘Fukuyutaka’ which distinctly differ in DFM relative to the difference in DSF. QTL analyses of DFM as well as DSF were carried out with the RIL population in three different years to extract the genetic factor(s) controlling the difference in DFM.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

An experimental RIL population was developed using a single seed decent method from a cross between ‘Ippon-Sangoh’ and ‘Fukuyutaka’. Fukuyutaka is a leading variety in southwest Japan. According to the USDA plant germplasm database (http://www.ars-grin.gov/npgs/acc/acc_queries.html), Fukuyutaka (PI 506675) is grouped in maturity group VI. Ippon-Sangoh is a Japanese landrace exhibiting earlier maturation compared with Fukuyutaka mainly by short DFM (Table 1). The population consisted of 143 RILs, and the developmental stages were investigated in the population at F6, F7 and F8 generations.

Table 1.

Comparison of the developmental periods between ‘Fukuyutaka’ and ‘Ippon-Sangoh’

| Year | DSFa | DFMa | DSMa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Fukuyutaka | Ippon-Sangoh | Differenceb | Fukuyutaka | Ippon-Sangoh | Differenceb | Fukuyutaka | Ippon-Sangoh | Differenceb | |

| 2006 | 40.4 ± 0.9 | 38.8 ± 1.1 | 1.6* | 65.4 ± 0.9 | 58.6 ± 0.9 | 6.8** | 105.8 ± 1.1 | 97.4 ± 0.9 | 8.4** |

| 2007 | 37.8 ± 1.1 | 37.0 ± 0.0 | 0.8n.s. | 67.2 ± 0.9 | 59.2 ± 1.1 | 8.0** | 105.4 ± 0.9 | 96.2 ± 1.1 | 8.0** |

| 2008 | 42.0 ± 0.0 | 39.2 ± 1.1 | 2.8* | 71.8 ± 1.1 | 62.0 ± 1.4 | 9.8** | 113.8 ± 1.1 | 101.2 ± 1.1 | 12.6** |

Each duration is indicated by average days ± standard deviation. The abbreviations are as follows, DSF: duration from sowing to flowering, DFM: duration from flowering to maturation, DSM: duration from sowing to maturation.

Subtraction of mean of Ippon-Sangoh from that of Fukuyutaka.

indicate significant differences between Fukuyutaka and Ippon-Sangoh at the 1% and 5% levels using Student’s t-test. The ‘n.s.’ indicates no significant difference.

Survey of developmental periods of each RIL

The RIL population and their parental varieties were planted in an experimental field of the National Agriculture Research Center for Kyushu Okinawa region (32°52′N, 130°44′E) in 2006, 2007 and 2008. All the plant materials were sown in standard sowing periods for the region, on 13 July in 2006, 19 July in 2007 and 8 July in 2008. Each line was planted in a single row of 1 m length spaced 70 cm apart and with a plant interval of 14 cm to give a plant population density of 10.2 plants/m2, thus every row contained around seven plants of each line. The parental varieties were sown in five rows with the same plant density. The flowering and maturation of the RILs and the parents were checked every two days. The date on which more than 80% of the plants flowered was recorded as the flowering date. This benchmark corresponded to stage R1 of the reproductive stages described by Fehr et al. (1977). The maturation date was defined as the date on which more than 80% of the plants defoliated and turned yellow with pods rattling when shaken. This almost corresponded to stage R8 (Fehr et al. 1977).

Molecular marker analysis and construction of a genetic linkage map

Total DNA was isolated from 10 mg flour of seeds (three seeds bulk per line) of the F6 generation with the use of an Automatic DNA Isolation System PI-50α (Kurabo, Osaka, Japan) in accordance with Plant DNA Extraction Protocol version 2. Polymorphic DNA markers were mainly analyzed by the SSR genotyping panel system in accordance with the previous report of Sayama et al. (2011). In addition to the 304 SSR loci present in the panel, 10 polymorphic SSR markers, Sat_128, Sat_148, Sat_366, Sat_403, Satt622, Satt718 (Song et al. 2004), Satt598 (Cregan et al. 1999) and FT1SSR9, FT3SSR1, FT3SSR2 (Sayama et al. 2010) were genotyped as described previously (Hwang et al. 2009) to fill the gap of the linkage group (LG). The linkage map was constructed using MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0b software (Lincoln et al. 1993). The linkage distance was estimated by the Kosambi mapping function (Kosambi 1944). For grouping the markers, a minimum logarithm of odds (LOD) score of 2.0 and a maximum distance 50.0 centi-Morgan (cM) were used as a threshold value to declare linkage in the pairwise loci analysis.

QTL analysis of the duration of each developmental period

QTL analysis was performed using Windows QTL Cartographer version 2.5 (Wang et al. 2007). A composite interval-mapping method (Zeng 1993, 1994) was implemented with a threshold value calculated by a permutation test (Churchill and Doerge 1994) to identify QTLs. The threshold LOD at 5% probability level calculated by thousands-times permutation test varied in a range of 3.0 to 3.5. To investigate genetic interactions among QTLs, ‘2D Genome Scan’ function of QTL Network software version 2.0 (Yang and Zhu 2005) was used. Using this function, it is possible to detect genetic interactions among major QTLs, as well as minor QTLs with a weak or non-significant single-locus effect.

Results

Difference in pre- and post-flowering periods

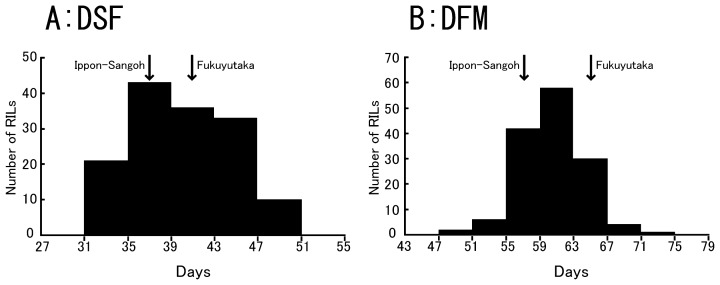

Ippon-Sangoh took 96 to 101 days for the total growth period (DSM), which was 8 to 13 days less than that of Fukuyutaka (Table 1). The post-flowering period (DFM) of Ippon-Sangoh was significantly shorter (7 to 10 days) than that of Fukuyutaka in all three seasons, while Ippon-Sangoh flowered about only 1 to 3 days earlier than Fukuyutaka (Table 1). Overall, the large difference in DSM between the two varieties was mainly caused by DFM. Two-way ANOVA on DFM and DSF in which year as a factor and soybean variety as another factor revealed that year, variety and their interaction were all significant at 1% or 5% significant level in both DFM and DSF (data not shown). This indicates that growth conditions also affected the DFM and DSF of Fukuyutaka and Ippon-Sangoh, even though response to the conditions was different between the varieties. The correlation coefficients among the durations of the developmental phases in the RIL population are shown in Table 2. Two developmental phases, DFM and DSF, significantly affected the total length of growth periods. On the other hand, the values of correlation coefficients between DSF and DFM were relatively low, and it was observed that there was no significant correlation between them in 2006. These results suggest that DSF and DFM may be controlled independently at some level. The frequency for DFM of the RILs was distributed continuously beyond the range of the parental varieties. DFM of the 143 RILs was distributed from 47 to 71 days in 2006, whereas the parents, Fukuyutaka and Ippon-Sangoh matured in 65.4 and 58.6 days after flowering, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). Similarly, DSF for the RILs was distributed continuously over the range of the parents (Fig. 1A). Significant positive year to year correlations (P < 0.001) were observed for both DSF and DFM, between any combinations of the three seasons (data not shown). These results suggested that DFM as well as DSF were quantitatively controlled by multiple loci over annual environmental differences.

Table 2.

Relationships among the developmental periods in RILs of ‘Ippon-Sangoh’ and ‘Fukuyutaka’

| Year | DFM | DSM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | DSF | −0.16n.s. | 0.71** |

| DFM | – | 0.58** | |

|

| |||

| 2007 | DSF | 0.26* | 0.69** |

| DFM | – | 0.88** | |

|

| |||

| 2008 | DSF | 0.34** | 0.82** |

| DFM | – | 0.82** | |

indicate significant differences of the correlation coefficient at the 1% and 5% levels. The ‘n.s.’ indicates no significant difference.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distributions of DSF and DFM observed in the recombinant inbred lines derived from the cross between ‘Ippon-Sangoh’ and ‘Fukuyutaka’ in 2006. DSF: duration from sowing to flowering (days), DFM: duration from flowering to maturation (days). Average values of parental phenotypes (Table 1) are indicated by arrows on each plate.

QTL analysis of pre- and post-flowering periods

In order to conduct the QTL analysis, a linkage map was constructed with the segregation data of 171 SSR loci in the 143 RILs. Within the 304 SSR loci composing the SSR genotyping panel of soybean (Sayama et al. 2011), 161 loci exhibited obvious polymorphisms in the RIL population. In addition, 10 polymorphic SSR loci were genotyped to fill gaps in each LG. The resultant linkage map for the RILs consisted of 20 LGs and covered a total of 2062 cM. The constructed LGs and the arrangement of SSR loci in each LG matched well with those in previous reports (Hwang et al. 2009, Sayama et al. 2011). QTL analysis was executed using this genetic linkage map. In the present study, the QTLs repeatedly detected at similar position on a chromosome in more than two seasons were considered to be stable. Further investigation was carried out for the stable QTLs. The stable QTLs for DSF and DFM are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2. The chromosome number and LG are defined in SoyBase (http://www.soybase.org/) and Cregan et al. (1999), respectively.

Table 3.

Details of the QTLs for DSF and DFM that were identified in at least two different years

| QTL (chromosome) | Developmental period | Year | LODa | Marker intervalb | Additive effectc | R2 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qDfm1 (Chr-11) | DFM | 2006 | 8.7 | Satt519-Satt583 | 1.9 | 0.23 |

| 2007 | 9.2 | Satt128-Satt519 | 2.6 | 0.26 | ||

| 2008 | 5.8 | Satt519-Satt583 | 1.9 | 0.17 | ||

|

| ||||||

| qDsf1 (Chr-16) | DSF | 2006 | 6.1 | Sat_339-Satt414 | −1.4 | 0.09 |

| 2007 | 13.0 | Sat_339-Satt414 | −1.5 | 0.19 | ||

| 2008 | 12.5 | Sat_339-Satt414 | −1.9 | 0.17 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Predicted E2 locus (Chr-10) | DSF | 2006 | 27.9 | Satt592-Sat_038 | 3.5 | 0.58 |

| 2007 | 24.7 | Satt592-Sat_038 | 2.4 | 0.49 | ||

| 2008 | 27.4 | Satt592-Sat_038 | 3.3 | 0.51 | ||

|

| ||||||

| DFM | 2007 | 3.2 | Satt592-Sat_038 | 1.6 | 0.09 | |

| 2008 | 3.1 | Satt592-Sat_038 | 1.5 | 0.10 | ||

Peak value of logarithm of odds score for QTL. The threshold for QTL detection was decided using a thousand-times permutation test (Churchill and Doerge 1994).

LOD peak for QTL located between the marker loci.

A positive value indicates that the Fukuyutaka allele increases the phenotypic value (days for DSF or DFM).

Proportion of phenotypic variance explained by the QTL.

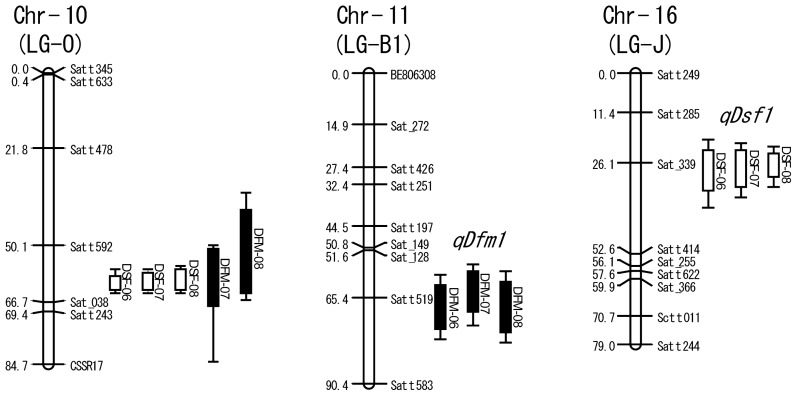

Fig. 2.

Locations of QTLs for DSF and DFM that were identified in at least two different years. QTLs for DSF and DFM are indicated by open bars and filled bars, respectively with lines at both ends. The bar and line indicate 1-logarithm of odds (LOD) and 2-LOD confidence interval (Ooijen 1992). Each marker name is shown on the right side of the linkage group, and cumulative map distance (in centi-Morgan) is shown on the left side. Three SSR loci, Sat_149, Sat_366 and Satt622 were reported by Song et al. (2004). The other loci were contained in the SSR panel of Sayama et al. (2011).

Two stable QTLs for DFM were detected on Chr-10 and 11. The locus on Chr-11 was detected in all three years, but the locus on Chr-10 was not detected in 2006. For both loci, alleles for long duration originated in Fukuyutaka. The QTL located on Chr-11 was named qDfm1 (quantitative trait locus for duration from flowering to maturation 1), because the locus gave stable and exclusive effects on DFM in all three years. In contrast, the QTL on Chr-10 was estimated to be E2 from its position (Cregan et al. 1999) and affected both DSF and DFM. Therefore, the putative E2 locus was not assigned a special name. Based on an additive effect of qDfm1, it was estimated that the locus brought about 3.8, 5.2 and 3.8 days difference of DFM in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively. As for the predicted E2 locus, it was estimated that the locus brought about 3.2 and 3.0 days difference of DFM in 2007 and 2008, respectively.

Two stable loci for DSF were detected on Chr-10 (LG-O) and 16 (LG-J). The QTL on Chr-16 was named qDsf1 (quantitative trait loci for duration from sowing to flowering 1), because the locus gave stable effects on DSF in all three years. In contrast, the QTL on Chr-10 was estimated to be E2, as indicated above, and thus the locus was not assigned a special name either. qDsf1 was estimated to bring about 2.8, 3.0 and 3.8 days difference in DSF in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively, based on additive effects. It should be considered that allele for early flowering originated in the late parent Fukuyutaka for qDsf1. As for the predicted E2 locus, it was estimated that 7.0, 4.8 and 6.6 days difference in DSF were brought about by the locus in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively.

In the three QTLs considered to exhibit stable effects, only the predicted E2 locus affected both DFM and DSF. The other two loci exhibited effects on only DFM and DSF, respectively, and this result was consistent with the fact that the correlation coefficient between DFM and DSF was relatively low in the trials in all three years. The epistatic effects of QTLs are important as well as the individual effect of these major QTLs. Therefore, epistatic interactions between the QTLs were investigated using version 2.0 of the QTL Network software for both periods studied in present study. As a result, no significant epistatic interaction between the QTLs was detected in DSF and DFM in all three years (data not shown).

The results obtained here suggested that qDfm1 played an important role in the control of DFM. However, there was a possibility that it exhibited a slight pleiotropic effect on DSF. For application of the locus in breeding programs, it is necessary to clarify the effect on DFM as well as on DSF. Thus, the effect of qDfm1 on DFM and DSF were examined with another way different from QTL analysis. The RIL population was classified for the genotype of Satt519, which is located close to qDfm1 (Fig. 2) and the difference in DFM and DSF of both genotypes was evaluated statistically. Prior to the comparison of DFM and DSF, it was verified that segregating ratios of Satt519 in RIL population fitted well with the expected ratio 1 : 1 by chi-square test (data not shown). The genotypes for qDfm1 corresponded well with the DFM of the RIL population in the three years, while a significant relationship between genotype and DSF was not observed (Table 4). RILs with the Fukuyutaka allele exhibited 3.4 to 5.1 days longer DFM compared with those for the Ippon-Sangoh allele (Table 4). This result was consistent with the result of the QTL analysis because the additive effect of qDfm1 ranged from 1.9 to 2.6 in QTL analysis, and this meant that qDfm1 controlled 3.8 to 5.2 days difference in DFM (Table 3). On the other hand, a significant difference in DSF was not observed between RILs with the Fukuyutaka allele and those with the Ippon-Sangoh allele (Table 4), although it should be considered that the P value of the difference in 2008 was 0.051, which was very close to the threshold of significance. Overall, it was suggested that qDfm1 had a negligible impact on DSF.

Table 4.

Relationships between developmental periods and genotypes of qDfm1 estimated using the proximal marker Satt519 in RILs of ‘Ippon-Sangoh’ and ‘Fukuyutaka’

| DSFa | DFMa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Year | Fukuyutaka type | Ippon- Sangoh type | Differenceb | Fukuyutaka type | Ippon-Sangoh type | Differenceb |

| 2006 | 40.7 ± 4.8 | 40.3 ± 4.1 | 0.4n.s. | 61.2 ± 3.4 | 57.8 ± 3.4 | 3.4** |

| 2007 | 38.5 ± 3.5 | 38.2 ± 3.3 | 0.3n.s. | 62.7 ± 4.2 | 57.6 ± 4.4 | 5.1** |

| 2008 | 41.8 ± 4.9 | 40.2 ± 4.1 | 1.6n.s. | 67.6 ± 4.0 | 63.6 ± 4.3 | 4.0** |

Each duration is shown as average days ± standard deviation.

Subtraction of mean of Ippon-Sangoh type from that of Fukuyutaka type.

indicates a significant difference between two genotypes at the 1% level using Student’s t-test. The ‘n.s.’ indicates no significant difference.

Discussion

In the present study, two soybean lines (Ippon-Sangoh and Fukuyutaka) exhibiting obviously different DFM but only slightly different DSF were examined to detect genetic factor(s) that controlled DFM but with a minimal influence on DSF. Our field evaluation of the flowering and maturation dates actually confirmed clear differences in DFM (around 7 to 10 days) between Ippon-Sangoh and Fukuyutaka in all three years trial, while they exhibited only slight differences in DSF (around 1 to 3 days). This stable tendency across the years suggested that the difference in DFM depended mainly on genetic difference between Fukuyutaka and Ippon-Sangoh instead of environmental errors. The existence of genetic factor(s) related to the difference in DFM was also suggested in an investigation of the RIL population. The DFM of RILs varied ranged from approximately 50 days to 70 days, whereas the year to year correlation coefficients of DFM were high. This suggested that genetic factor(s) affecting DFM segregated in the population. In addition, another interesting result was obtained in the investigation of the RILs. The correlation coefficients between DFM and DSF in the RIL population were relatively low during the three years and were not statistically significant in 2006. On the other hand, it was suggested that the influence of environmental errors on the durations was limited in our data because the year to year correlation coefficients were high for both DFM and DSF. From these results of DFM and DSF, it is reasonable to consider that genetic factor(s) that differed in their effect on DFM and DSF were segregating in the population.

By investigation of Fukuyutaka, Ippon-Sangoh and their RIL population, the existence of genetic factor(s) that affect mainly DFM was suggested. In the QTL analysis by means of composite interval mapping method, two stable loci for DFM were detected (Table 3). For the subjects of present study, most noteworthy locus is qDfm1. The locus was stably detected in all three years, and its LOD score, additive effect, and R2 value were higher than those of the other QTL for DFM. In a classification test of the RILs using flanking marker genotypes, the effect of qDfm1 on DFM was confirmed in all three years. Therefore, it is clear that qDfm1 affects DFM. On the other hand, the effect of qDfm1 on DSF was not significant. These characteristics of qDfm1, affecting only DFM, coincide with that of genetic factor(s) sought in this study. Based on the effect of qDfm1 confirmed in genotype classification test of RILs, roughly half of the difference in DFM between Fukuyutaka and Ippon-Sangoh appears to depend on this locus. Thus, it is clear that qDfm1 is a genetic factor targeted in this study. Around the position of qDfm1, any other genetic factor that significantly affects DFM but has a minimal influence on DSF has not been reported so far. Therefore, the identification of qDfm1 provides definitive progress in the understanding of genetic control of the developmental period of soybean. Furthermore, there are some interesting reports related to qDfm1. Close to the position of qDfm1, Matsui et al. (2005) detected a major QTL for post-flowering period, in different varieties. Unfortunately, comparing the characteristics of this QTL and qDfm1 is difficult because effect of the QTL for DSF was not mentioned in the report, but it is possible that qDfm1 and the locus detected by Matsui et al. are identical. Some QTLs for pre-flowering period were also detected around the position of qDfm1 (Xin et al. 2008, Yamanaka et al. 2001, Zhang et al. 2004). Because of differences in the characteristics of these QTLs and qDfm1, further investigation of their effects and allelism is required for better understanding of the function and identity of the QTLs. Again, to clarify allelism and the characteristics of the effect on the developmental period is also required for the application of qDfm1 in breeding programs for yield improvement.

Another QTL for DFM was also identified in present study. The QTL on Chr-10 influenced DFM in 2007 and 2008. As for this QTL, a strong QTL for DSF was also detected at almost same position across three years (Table 3 and Fig. 2). In addition, it was reported that the E2 gene is located near this position (Cregan et al. 1999). In a previous study, it was revealed that E2 affect both pre- and post-flowering period (McBlain et al. 1987). This finding coincided well with our result that a QTL for DFM and DSF was detected at almost the same position. These findings strongly suggested that the QTL detected on Chr-10 is E2. Based on a previous report (McBlain et al. 1987), it has been established that E2 affects both DFM and DSF, thus this QTL should be excluded from further analysis related to yield improvement by DFM alteration. In contrast with the putative E2 locus, qDsf1 is interesting in terms of the independent control of DFM and DSF. This QTL stably affected only DSF across three years. Thus it could be possible to alter DSF genetically with little influence on DFM. Although, the importance of DSF itself to soybean yield has not been clarified so far, genetically alteration of DSF could lead to change in the balance between DFM and DSF. Kantolic and Slafer (2001) argued that an appropriate balance between pre- and post-flowering periods may result in higher yield potential. The use of qDsf1 could contribute to yield improvement via altering the balance of DFM and DSF. Around the position of qDsf1, Tasma et al. (2001) reported a QTL for days to R1, R3 and R7. On the other hand, Orf et al. (1999) detected a weak QTL for post-flowering period near the location of qDsf1. Interestingly, the QTL did not affect DSF, thus its characteristics clearly differ from qDsf1. There appears to be some differences in the characteristics of this QTL and qDsf1; therefore, further investigation in effect and allelism of them might be necessary if use is to be made of qDsf1 in breeding programs.

In the present study, genetic factors that control DFM with minimal influence on DSF were elucidated with the aim of improving yield by altering DFM. Using QTL analysis, a genetic factor named qDfm1 that fulfills this aim was identified. Therefore, it might be possible to develop plant materials with altered DFM utilizing information from flanking SSR markers. There have been few reports about attempts to improve the yield of soybean via genetic manipulation of independent DFM. Plant materials such as a series of NILs of qDfm1 that exhibit different DFM could propel the investigation of yield improvement and contribute to breeding programs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics for Agricultural Innovation [DD-3260 and SOY2005]). We thank Yumi Nakamoto of National Agricultural Research Center for Hokkaido Region for her excellent support in data processing to support our QTL analysis.

Literature Cited

- Bernard RL. Two genes for time to flowering and maturity in soybean. Crop Sci. 1971;11:242–244. [Google Scholar]

- Bonato ER, Vello NA. E6, a dominant gene conditioning early flowering and maturity in soybeans. Genet Mol Biol. 1999;22:229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell R. Inheritance of a soybean flowering response to fluorescent-daylength conditions. Can J Genet Cytol. 1971;13:703–707. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell RI, Voldeng HD. Inheritance of insensitivity to long daylength. Soybean Genet Newsl. 1980;7:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Wang Y, Zhang C, Wu C, Xu J, Zhu H, Leng J, Bai Y, Guan R, Hou W, et al. Genetic analysis and QTL detection of the reproductive period and post-flowering photoperiod responses in soybean. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill GA, Doerge RW. Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics. 1994;138:963–971. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cober ER, Tanner JW, Voldeng HD. Genetic control of photoperiod response in early-maturing, near-isogenic soybean lines. Crop Sci. 1996;36:601–605. [Google Scholar]

- Cober ER, Stewart DW, Voldeng HD. Photoperiod and temperature responses in early-maturing near-isogenic soybean lines. Crop Sci. 2001;41:721–727. [Google Scholar]

- Cober ER, Voldeng HD. A new soybean maturity and photoperiod-sensitivity locus linked to E1 and T. Crop Sci. 2001;41:698–701. [Google Scholar]

- Cober ER, Molnar SJ, Charette M, Voldeng HD. A new locus for early maturity in soybean. Crop Sci. 2010;50:524–527. [Google Scholar]

- Cregan PB, Jarvik T, Bush AL, Shoemaker RC, Lark KG, Kahler AL, Kaya N, Vantoai TT, Lohnes DG, Chung J, et al. An integrated genetic linkage map of the soybean genome. Crop Sci. 1999;39:1464–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr WR, Caviness CE. Special report 80, Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station. Iowa State University; Ames: 1977. Stages of soybean development; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherly LG, Elmore RW. Managing inputs for peak production. In: Boerma HR, Specht JE, editors. SOYBEANS: Improvement, Production, and Uses. Third Edition. American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America and Soil Science Society of America; Madison: 2004. pp. 451–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T-Y, Sayama T, Takahashi M, Takada Y, Nakamoto Y, Funatsuki H, Hisano H, Sasamoto S, Sato S, Tabata S, et al. High-density integrated linkage map based on SSR markers in soybean. DNA Res. 2009;16:213–225. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantolic AG, Slafer GA. Photoperiod sensitivity after flowering and seed number determination in indeterminate soybean cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2001;72:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kantolic AG, Slafer GA. Reproductive development and yield components in indeterminate soybean as affected by post-flowering photoperiod. Field Crops Res. 2005;93:212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, Diers BW, Olson TC, Shoemaker RC. RFLP mapping in soybean: Association between marker loci and variation in quantitative traits. Genetics. 1990;126:735–742. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.3.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosambi DD. The estimation of map distance from recombination values. Ann Eugenics. 1944;12:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kumudini SV, Pallikonda PK, Steele C. Photoperiod and E-genes influence the duration of the reproductive phase in soybean. Crop Sci. 2007;47:1510–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln SE, Daly MJ, Lander ES. MAPMAKER/EXP. Whitehead Institute of Biomedical Research; Cambridge, MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Nakasaki T, Okumoto Y, Kataita M, Sayama T, Kim S, Yoshikawa T, Tanisaka T. QTL analysis of flowering and maturing time in soybean. Breed. Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):279. [Google Scholar]

- McBlain BA, Bernard RL. A new gene affecting the time of flowering and maturity in soybean. J Hered. 1987;78:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- McBlain BA, Hesketh JD, Bernard RL. Genetic effects on reproductive phenology in soybean isolines differing in maturity genes. Can J Plant Sci. 1987;67:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Messina CD, Jones JW, Boot KJ, Vallejos CD. A gene-based model to simulate soybean development and yield response to environment. Crop Sci. 2006;46:456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Ooijen JW. Accuracy of mapping quantitative trait loci in autogamous species. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;84:803–811. doi: 10.1007/BF00227388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orf JH, Chase K, Jarvik T, Mansur LM, Cregan PB, Adler FR, Lark KG. Genetics of soybean agronomic traits: I. Comparison of three related recombinant inbred populations. Crop Sci. 1999;39:1642–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Saindon G, Beversdorf WD, Voldeng HD. Adjustment of the soybean phenology using the E4 locus. Crop Sci. 1989;29:1361–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Sayama T, Hwang T-Y, Yamazaki H, Yamaguchi N, Komatsu K, Takahashi M, Suzuki C, Miyoshi T, Tanaka Y, Xia Z, et al. Mapping and comparison of quantitative trait loci for soybean branching phenotype in two locations. Breed Sci. 2010;60:380–389. [Google Scholar]

- Sayama T, Hwang T-Y, Komatsu K, Takada Y, Takahashi M, Kato S, Sasama H, Higashi A, Nakamoto Y, Funatsuki H, et al. Development and application of a whole-genome simple sequence repeat panel for high-throughput genotyping in soybean. DNA Res. 2011;18:107–115. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song QJ, Marek LF, Shoemaker RC, Lark KG, Concibido VC, Delannay A, Specht JE, Cregan PB. A new integrated genetic linkage map of the soybean. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109:122–128. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasma IM, Lorenzen LL, Green DE, Shoemaker RC. Mapping genetic loci for flowering time, maturity, and photoperiod insensitivity in soybean. Mol Breed. 2001;8:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng Z-B. Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5. Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University; Raleigh, NC: 2007. http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Tajuddin T, Yamanaka N, Hayashi M, Harada K. Analysis of QTLs for reproductive development and seed quality traits in soybean using recombinant inbred lines. Breed Sci. 2004;54:399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Xin D-W, Qiu H-M, Shan D-P, Shan C-Y, Liu C-Y, Hu G-H, Staehelin C, -S Q. Analysis of quantitative trait loci underlying the period of reproductive growth stages in soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.) Euphytica. 2008;162:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N, Ninomiya S, Hoshi M, Tsubokura Y, Yano M, Nagamura Y, Sasaki T, Harada K. An informative linkage map of soybean reveals QTLs for flowering time, leaflet morphology and regions of segregation distortion. DNA Res. 2001;8:61–72. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.2.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhu J. Methods for predicting superior genotypes under multiple environments based on QTL effects. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;110:1268–1274. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-1963-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng ZB. Theoretical basis for separation of multiple linked gene effects in mapping quantitative trait loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 1993;90:10972–10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng ZB. Precision mapping of quantitative trait loci. Genetics. 1994;136:1457–1468. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.4.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W-K, Wang Y-J, Luo G-Z, Zhang J-S, He C-Y, Wu X-L, Gai J-Y, Chen S-Y. QTL mapping of ten agronomic traits on the soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) genetic map and their association with EST markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:1131–1139. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]