Abstract

The Krüppel homolog 1 gene (Kr-h1) has been proposed to play a key role in the repression of insect metamorphosis. Kr-h1 is assumed to be induced by juvenile hormone (JH) via a JH receptor, methoprene-tolerant (Met), but the mechanism of induction is unclear. To elucidate the molecular mechanism of Kr-h1 induction, we first cloned cDNAs encoding Kr-h1 (BmKr-h1) and Met (BmMet1 and BmMet2) homologs from Bombyx mori. In a B. mori cell line, BmKr-h1 was rapidly induced by subnanomolar levels of natural JHs. Reporter assays identified a JH response element (kJHRE), comprising 141 nucleotides, located ∼2 kb upstream from the BmKr-h1 transcription start site. The core region of kJHRE (GGCCTCCACGTG) contains a canonical E-box sequence to which Met, a basic helix–loop–helix Per-ARNT-Sim (bHLH–PAS) transcription factor, is likely to bind. In mammalian HEK293 cells, which lack an intrinsic JH receptor, ectopic expression of BmMet2 fused with Gal4DBD induced JH-dependent activity of an upstream activation sequence reporter. Meanwhile, the kJHRE reporter was activated JH-dependently in HEK293 cells only when cotransfected with BmMet2 and BmSRC, another bHLH–PAS family member, suggesting that BmMet2 and BmSRC jointly interact with kJHRE. We also found that the interaction between BmMet2 and BmSRC is dependent on JH. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis for the mechanism of JH-mediated induction of BmKr-h1: BmMet2 accepts JH as a ligand, JH-liganded BmMet2 interacts with BmSRC, and the JH/BmMet2/BmSRC complex activates BmKr-h1 by interacting with kJHRE.

Keywords: development, insecticide, steroid receptor coactivator

Juvenile hormone (JH) regulates various aspects of development and physiology in insects including metamorphosis, reproduction, diapause, and polyphenism (1–3). For controlling metamorphosis, JH works in close cooperation with molting hormone (ecdysteroids) to prevent larvae from precociously turning into adults (status quo action). Although the mode of action of ecdysteroids in metamorphosis is well understood at the molecular level (4, 5), that of JH is largely unknown (6).

Methoprene-tolerant (Met), a transcription factor of the basic helix–loop–helix Per-ARNT-Sim (bHLH–PAS) gene family, was identified in a Drosophila melanogaster mutant that showed resistance to toxic doses of JH or its analog methoprene (JHA) (7, 8). Met showed high affinity for JH, and when fused to the yeast GAL4-DNA binding domain (GAL4DBD), it exhibited JH-dependent activation of an upstream activation sequence (UAS) reporter gene in Drosophila S2 cells (9). In the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum, injection of Met dsRNA (TcMet) caused precocious metamorphosis, indicating that Met is involved in antimetamorphic JH signaling (10, 11).

Proteins of the bHLH–PAS family often function in the form of homodimers or heterodimers (12, 13). In D. melanogaster, the germ-cell expressed gene (gce), a bHLH–PAS family member, has high sequence identity to Met and works as a JH-sensitive binding partner of Met (14). Further, Met and GCE have overlapping functions in the JH signaling pathway (15) and regulate caspase genes involved in programmed cell death during metamorphosis (16). Moreover, Met and SRC (p160/SRC, a steroid receptor coactivator; also known as “FISC” or “Taiman”) form a complex and directly activate the transcription of the early trypsin gene during reproduction of Aedes aegypti (17). Recently, TcMet has been shown to sense the JH signal through direct, specific binding and to interact with SRC, thus establishing TcMet as a JH receptor (18).

With regard to JH-inducible genes, the Krüppel homolog 1 gene (Kr-h1), a C2H2 zinc-finger type transcription factor, was identified from D. melanogaster as a JH early-inducible gene (19). We reported that the Kr-h1 homolog in T. castaneum (TcKr-h1) also is induced rapidly by JH, and knockdown of TcKr-h1 causes precocious metamorphosis (20), as is seen in the knockdown of TcMet (10, 11). Moreover, an RNAi silencing analysis showed that TcKr-h1 works downstream of TcMet (20). Taken together, the available information indicates that Kr-h1 may play a primary role in the repression of metamorphosis in close cooperation with Met.

In this study, we sought to clarify the molecular mechanism of JH-mediated induction of Kr-h1 in Bombyx mori. The promoter region of Kr-h1 of B. mori (BmKr-h1) was searched for a JH response element (JHRE) by using reporter assays in a B. mori cell line (NIAS-Bm-aff3). We found that the JHRE of BmKr-h1 (kJHRE) is distinct from previously reported JHREs in that it contains an E-box to which bHLH–PAS proteins could bind. Next, we searched for a transcription factor that interacts with kJHRE by using reporter assays in mammalian HEK293 cells, which are believed to lack JH signaling pathways. On the basis of our findings, we propose a transcriptional mechanism for the JH-mediated induction of BmKr-h1.

Results

Structures of B. mori Kr-h1, Met, and SRC.

cDNAs encoding two BmKr-h1 isoforms, BmKr-h1α (AB360766) and BmKr-h1β (AB642242), were identified in the full-length cDNA library prepared from the corpora allata–corpora cardiaca (CA–CC) complex of B. mori (Fig. S1A). BmKr-h1α and BmKr-h1β had ORFs encoding proteins of 348 and 361 amino acid residues, respectively. The transcription start site of BmKr-h1β was located in the first intron of BmKr-h1α (Fig. S1A). BmKr-h1α and BmKr-h1β each have eight putative zinc-finger domains, which shared high homology with those of Kr-h1 of other insect species (Fig. S1B).

A tblastn search of the silkworm genomic database identified two Met homologs (BmMet1 and BmMet2) and an SRC homolog (BmSRC). The full-length cDNAs of BmMet1 (AB359911), BmMet2 (AB359912), and BmSRC (AB703620), obtained by RACE, encoded proteins with 514, 808, and 1,221 amino acid residues, respectively. BmMet1 had no introns, but BmMet2 had nine introns in positions similar to those of DmGCE and TcMet (Fig. S2 A and B). Four domains, bHLH, PASA, PASB, and PAC, were well conserved among the Met homologs of the insect species examined (Fig. S2B).

Developmental and Hormonal Regulation of BmKr-h1 in B. mori Larvae.

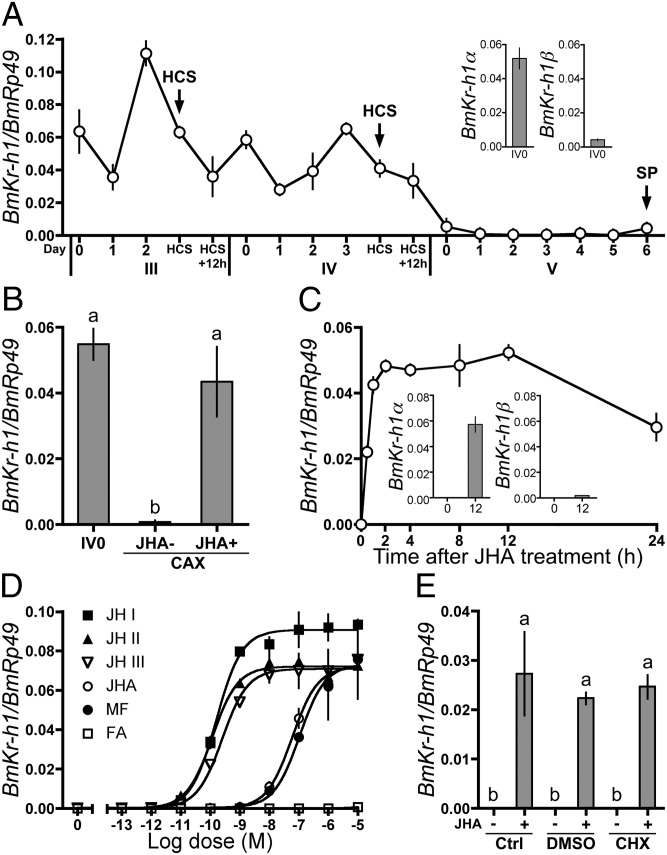

The developmental expression profile of BmKr-h1 in the epidermis of B. mori larvae was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 1). The analysis with isoform-specific primers revealed that BmKr-h1α is predominant in the larval epidermis (Fig. 1A Inset). In the following experiments, we used primers that amplify both isomers unless otherwise mentioned. BmKr-h1 was constitutively expressed in third- and fourth-instar larvae, with some fluctuations, but its expression declined to a trace level at day 0 in the fifth instar and remained at this level until spinning. The expression pattern of BmKr-h1 showed a good correlation with the changes in the JH titer in the hemolymph of B. mori (21), suggesting the involvement of JH in the regulation of BmKr-h1 expression during the larval stages. To test this notion, the CA, the primary organs for JH synthesis, were removed from fourth-instar larvae at day 0, and the expression of BmKr-h1 was monitored (Fig. 1B). In allatectomized larvae, the BmKr-h1 transcript decreased prematurely to a trace level. In contrast, the transcript was maintained at a high level in allatectomized larvae treated with JHA (Fig. 1B). These results clearly showed that the expression of BmKr-h1 was positively regulated by JH in B. mori larvae, as has been reported in other insect species (19, 20, 22, 23).

Fig. 1.

Regulation of BmKr-h1 expression by JH in B. mori larvae and NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells. BmKr-h1 expression levels were determined by qPCR. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 except in A, where n = 2). Means with the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey–Kramer test, P < 0.05). (A) Developmental expression profiles of BmKr-h1 in the epidermis. (Inset) Expression levels of BmKr-h1α and BmKr-h1β in fourth-instar larvae at day 0. Roman and Arabic numerals under the horizontal axis indicate the instar and days in the instar, respectively. HCS, head capsule slippage; SP, spinning. (B) Effects of allatectomy (CAX) and methoprene (JHA) treatment on BmKr-h1 expression. Fourth-instar larvae at day 0 were treated with either JHA (1 μg) or acetone (JHA−) 3 h after allatectomy. Twelve hours later the epidermis was dissected, and BmKr-h1 expression was measured. (C) NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells were treated with 10 μM JHA, and temporal changes in BmKr-h1 expression were monitored. (Inset) Expression levels of BmKr-h1α and BmKr-h1β in cells treated with JHA for 0 and 12 h. (D) NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells were treated with different concentrations of JH (JH I, JH II, and JH III), JHA, MF, or FA, and the relative expression levels of BmKr-h1 were determined after 2 h. (E) Untreated cells (Ctrl) or cells precultured in a medium with 50 μM CHX or solvent only (DMSO, 3% vol/vol) for 1 h were treated with 1 μM JHA or solvent for 2 h, and the relative expression levels of BmKr-h1 were determined.

Effects of JH and Its Analogs on BmKr-h1 Expression in B. mori Cells.

Next, we examined the effect of JH and related compounds on the expression of BmKr-h1 in NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells, which are derived from the fat body of B. mori (24, 25). The BmKr-h1 transcript was barely detectable before the JHA treatment; however, this level increased significantly within 0.5 h of treatment and was 3.8 × 105-fold higher by 2 h after treatment (Fig. 1C). The JHA treatment induced the expression of both BmKr-h1α and BmKr-h1β (Fig. 1C); however, the expression level of BmKr-h1α was 30-fold higher, consistent with the level in the epidermis (Fig. 1 A and C). Dose-dependent increases in the BmKr-h1 transcript level were observed in cells treated with JH I, JH II, JH III, JHA, or methyl farnesoate (MF); the median effective concentrations (EC50) were 1.6 × 10−10, 1.2 × 10−10, 2.6 × 10−10, 6.0 × 10−8, and 1.1 × 10−7 M, respectively (Fig. 1D). Farnesoic acid (FA) was ineffective. The analysis clearly demonstrated that BmKr-h1 was responsive to subnanomolar levels of natural JHs of B. mori (i.e., JH I and JH II). Treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) had no significant effect on the level of the BmKr-h1 transcript (Fig. 1E), indicating that the JH-dependent induction of BmKr-h1 was not mediated by de novo synthesized protein.

Identification of kJHRE in BmKr-h1.

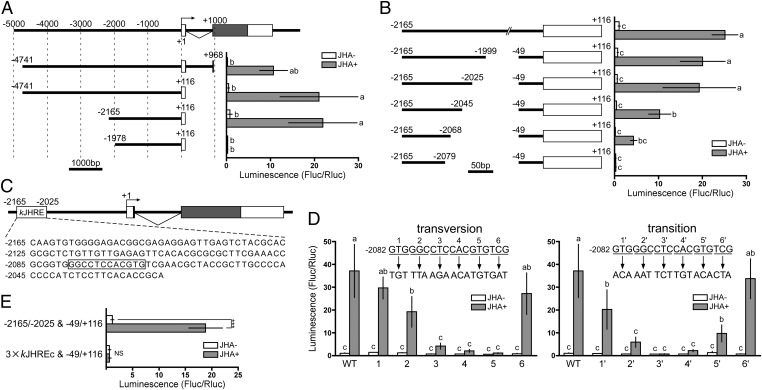

To account for the extremely high responsiveness of BmKr-h1 to JH in NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells, we searched for a JHRE in the promoter region of BmKr-h1 by using reporter assays. Because the expression of BmKr-h1β was marginal (Fig. 1 A and C), we focused on the promoter region of BmKr-h1α in this study. First, we tested several constructs carrying the upstream region of BmKr-h1 with a range of deletions (−4741 to +968, −4741 to +116, −2165 to +116, and −1978 to +116; Fig. 2A). All constructs, except that carrying the shortest region (−1978 to +116), showed a 30- to 60-fold increase in luciferase reporter activity in the presence of JHA, suggesting that the JHRE lies between −2165 and −1978. Subsequent reporter assays of constructs carrying deletions of various lengths within this region showed that the region crucial for the response to JH is −2165 to −2025 (Fig. 2B). Hereafter, this region is referred to as “kJHRE.”

Fig. 2.

Identification of kJHRE in BmKr-h1. Reporter assays with progressive deletion and mutation constructs were used to identify the JHRE. NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells were cotransfected with pGL4.14 reporter plasmids carrying the indicated promoter regions conjugated to firefly luciferase and a reference reporter plasmid carrying Renilla luciferase. The cells were treated with 10 μM methoprene (JHA) for 24 h, and reporter activities were measured by using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system. The activities of firefly luciferase were normalized against those of Renilla luciferase in the same samples. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3). Means with the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey–Kramer test, P < 0.05). Some data were analyzed using Student’s t test (***P < 0.001; NS, P > 0.05). (A) Reporter plasmids containing the 5′-flanking and first intron regions of BmKr-h1α were assayed. The structure of BmKr-h1 is shown at the top. Numbers indicate the distance from the transcription start site (+1), and white and shaded boxes represent the untranslated and coding regions of exons, respectively. Reporter activities of progressive deletion constructs are shown below. (B) The insert in the plasmid used in A, the −2165 to +116 region, was reduced progressively from −49 toward −2079, and the effects were measured by reporter assays. (C) Schematic representation of the location of kJHRE (−2165 to −2025). The nucleotide sequence is shown below the gene structure. Boxed letters are indispensable sequences (kJHREc). (D) The functionality of kJHREc was assayed with mutations causing a triplet transversion (Left) or transition (Right) in the −2082 to −2065 region of the kJHRE reporter (−2165 to −2025 and −49 to +116, pGL4.14). (E) The JH response of a reporter carrying three tandem copies of kJHREc was examined.

GTG, CAC, GAG, and CTC sequences appeared repeatedly in kJHRE (Fig. 2C), suggesting that they might be important for the response to JH. To pinpoint nucleotide sequences within kJHRE indispensable for the JH response, we constructed reporter plasmids with various mutations in the kJHRE sequence and examined their responses to JHA in reporter assays (Fig. S3). The response to JHA decreased by more than sixfold when a mutation was introduced into −2105CACAC, −2082GTG, −2073CACGTGT, −2101CGCGCGC, −2086CGCG, or −2076CTC (Fig. S3 A and B). In particular, the induction by JHA was abolished when −2076CTC or −2073CACGTGT was mutated (Fig. S3 A and B). Subsequently, mutations were introduced in the region from −2082 to −2065. Reporter activity was reduced drastically when the region from −2079 to −2068 (GGCCTCCACGTG) was changed (Fig. 2D). This 12-bp sequence, which we refer to as the “kJHRE core region” (kJHREc), contained a palindromic canonical E-box sequence (CACGTG) (Fig. 2C) to which bHLH–PAS transcription factors have been shown to bind (26). Although kJHREc is indispensable for the response to JH, a reporter vector carrying three tandem copies of kJHREc did not show any response to JHA (Fig. 2E); therefore, the regions flanking kJHREc, −2165 to −2080 and −2067 to −2025, also are important for the response to JH (Fig. 2C). These regions, however, contained no conserved sequence motifs that interact with transcription factors (Fig. 2C).

With regard to the basal promoter region, when the reporter was placed under the regulation of the −2165 to −2025 and −49 to +116 sequence, it exhibited the same level of activity as when regulated by the −2165 to +116 sequence (Fig. 2B). Because even a slight shortening of the −49 to +116 sequence decreased reporter activity (Fig. S4A), this region was determined to be the optimal basal promoter. When this promoter was replaced by the promoter for actin or Hsp70 of B. mori (BmA3 or BmHSP70), reporter activity still was strongly induced by JHA (15- to 48-fold) (Fig. S4B), indicating that a specific basal promoter is not essential for the JH responsiveness of kJHRE.

Conservation of Putative kJHREc in the Kr-h1 Promoters of Other Insect Species.

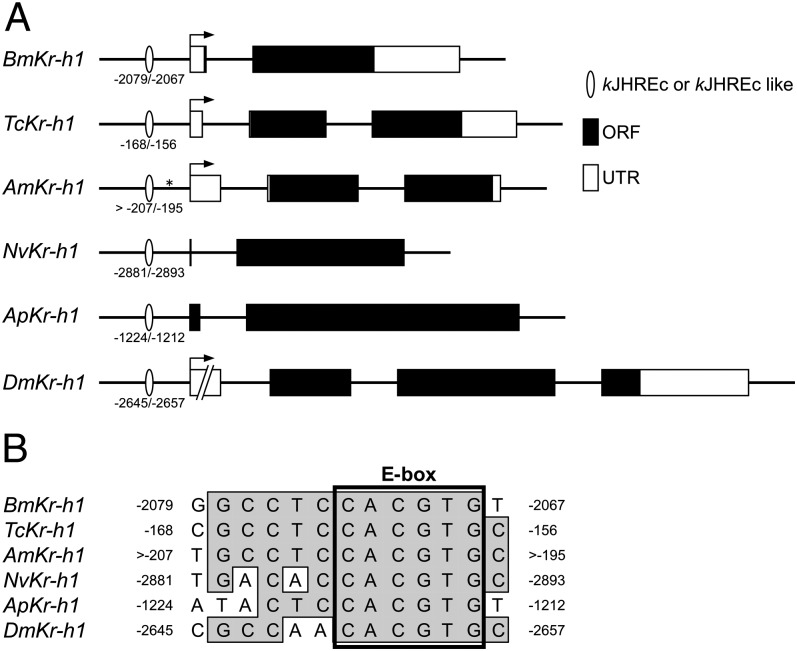

Public genomic databases were screened for sequences with homology to kJHREc in the promoters of Kr-h1 of other insect species. Sequences with similarity to kJHREc were found in the 3-kb upstream region from the transcription or translation start sites of Kr-h1 in T. castaneum, Apis mellifera, Nasonia vitripennis, Acyrthosiphon pisum, and D. melanogaster (Fig. 3A). All these sequences possessed the identical E-box sequence, but some differences were present in the 5′-half region of the putative kJHREc (Fig. 3B). No conserved sequence other than the E-box sequence was found in the vicinity of kJHREc-like sequences of other insect species.

Fig. 3.

Predicted kJHREc of Kr-h1 in other insect species. (A) Genomic structures and putative kJHREc positions are shown: Am, A. mellifera; Ap, A. pisum; Bm, B. mori; Dm, D. melanogaster; Nv, N. vitripennis; Tc, T. castaneum. White boxes, black boxes, and arrows represent the UTRs, ORFs, and transcription start sites, respectively. Ellipses indicate putative kJHREc, and the numbers below represent distances from the transcription start site (BmKr-h1, TcKr-h1, AmKr-h1, and DmKr-h1) or translation start site (NvKr-h1 and ApKr-h1). The position marked with an asterisk in AmKr-h1 represents a gap in the available genomic information. (B) Alignment of the putative kJHREc sequences in the 5′-flanking region of Kr-h1.

Interactions of JH, BmMet2, BmSRC, and kJHRE in Mammalian Cells.

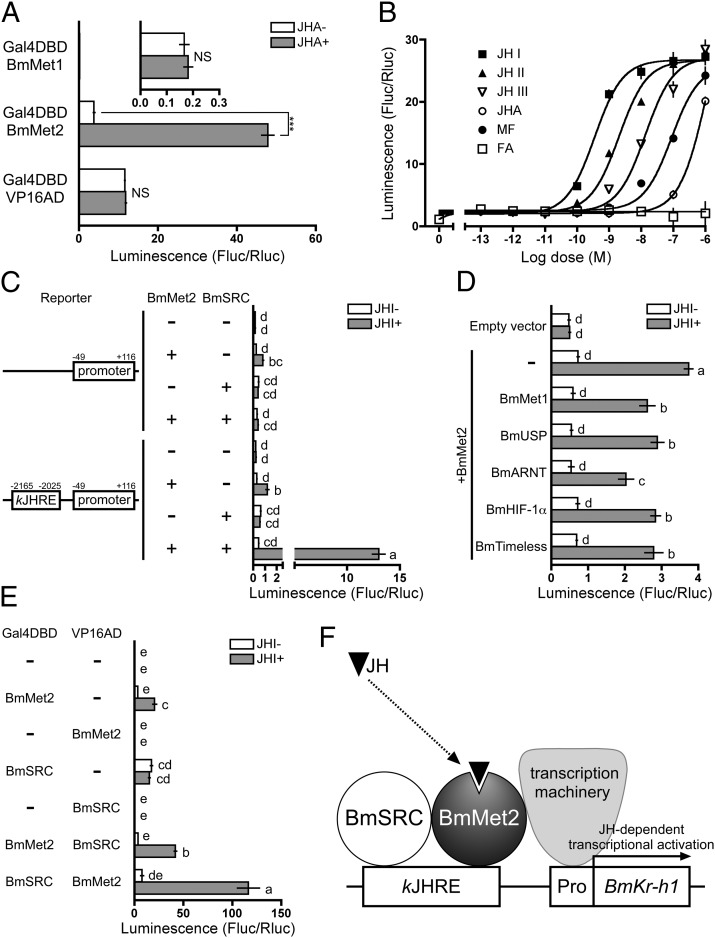

The function of BmMet2 in JH signaling was examined by one-hybrid reporter assays in the HEK293 mammalian cell line. When the N terminus of BmMet2 was fused to Gal4DBD and expressed in HEK293 cells, the activity of the UAS reporter increased significantly in the presence of JHA (Fig. 4A). No JHA-dependent increase in UAS reporter activity was observed in cells expressing BmMet1 or VP16AD (control) fused with Gal4DBD (Fig. 4A). In addition to JHA, natural JHs and MF, but not FA, induced UAS reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner in HEK293 cells expressing BmMet2 fused with Gal4DBD (Fig. 4B). The EC50 values of JH I, JH II, JH III, JHA, and MF were 3.5 × 10−10, 2.0 × 10−9, 1.4 × 10−8, 1.2 × 10−6, and 8.8 × 10−8 M, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Functional analysis of BmMet2 and kJHRE in mammalian HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells were treated as described below, and reporter activity was examined by using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3). Means with the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey–Kramer test, P < 0.05). Some data were analyzed using Student’s t test (***P < 0.001; NS, P > 0.05). (A) Cells were cotransfected with a UAS reporter plasmid carrying firefly luciferase, a reference reporter plasmid (pRL-TK) carrying Renilla luciferase, and an expression plasmid carrying GAL4DBD fused with BmMet1, BmMet2, or VP16AD and were treated with 10 μM methoprene (JHA) for 24 h. (B) Cells were cotransfected with the UAS reporter plasmid and the expression plasmid carrying GAL4DBD fused with BmMet2 and were treated with the indicated concentrations of JH, JHA, MF, or FA for 24 h. (C) Cells were cotransfected with a kJHRE-reporter plasmid and an expression plasmid carrying native BmMet2 or BmSRC, and were treated with 0.1 μM JH I for 24 h. (D) Cells were cotransfected with a kJHRE-reporter plasmid, BmMet2 expression plasmid, and an expression plasmid carrying BmMet1, BmUSP, BmARNT, BmHIF-1α, or BmTimeless. (E) Cells were cotransfected with the UAS-reporter plasmid and an expression plasmid carrying GAL4DBD or VP16AD fused with BmMet2 or BmSRC and were treated with 0.1 μM JH I for 24 h. (F) A model for JH-mediated transcriptional induction of BmKr-h1. The physical interaction between kJHRE and BmMet2/BmSRC complex remains to be determined.

To identify the transcription factors that interact with kJHRE in association with BmMet2, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with an expression vector carrying a candidate gene and kJHRE reporter vector carrying −2165 to −2025 and −49 to +116, and their response to JH I was evaluated in reporter assays. The reporter activity was stimulated weakly by JH in HEK293 cells expressing native BmMet2 alone (Fig. 4C). However, the reporter carrying only the basal promoter also was stimulated by JH (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the activities induced in the presence of BmMet2 alone were not kJHRE specific. When BmSRC was coexpressed with BmMet2 in HEK293, strong JH-dependent and kJHRE-specific reporter activity (27-fold) was observed (Fig. 4C). Meanwhile, coexpression of BmMet1, BmUSP, BmARNT, BmHIF-1α, or BmTimeless with BmMet2 did not increase the JH-dependent reporter activity from the level induced by BmMet2 alone (Fig. 4D).

Subsequently, the interaction between BmMet2 and BmSRC was analyzed in detail by using two-hybrid reporter assays in HEK293 cells. The UAS reporter activity in cells expressing Gal4DBD–BmMet2 was stimulated by JHA, as shown in Fig. 4A, and coexpression of VP16AD–BmSRC increased the activity twofold (Fig. 4E). A JHA-dependent increase in UAS reporter activity (667-fold) also was observed in HEK293 cells coexpressing an alternative set of fusion proteins, Gal4DBD–BmSRC and VP16AD–BmMet2, whereas no JH-dependent increase was observed in cells expressing VP16AD–BmMet2 alone (Fig. 4E). These results demonstrate that the interaction of BmMet2 with BmSRC is JH dependent.

Discussion

Elucidation of JH signaling at the molecular level has been a challenge in insect physiology and developmental biology. Here, we provide evidence that BmKr-h1 possesses the properties of a primary mediator of JH signaling.

The developmental expression profile and the allatectomy experiment showed that BmKr-h1 was positively regulated by JH in B. mori larvae. The characteristic induction of BmKr-h1 by JH also was observed in NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells. BmKr-h1 expression in NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells was induced within 30 min of the initiation of JHA treatment, and the expression level approached the peak level by 1 h. Moreover, because inhibition of protein synthesis by CHX did not have a significant effect on the level of the BmKr-h1 transcript, transcription of BmKr-h1 likely represents a primary response to JH. Many JH-inducible genes, such as jhp21 (27), JH esterase (28, 29), calmodulin (30), vitellogenin (31), Epac (32), E75 (33), and others (34–37), have been reported. However, induction of BmKr-h1 occurred at considerably lower (subnanomolar) concentrations of natural JHs (EC50 = 1.2–2.6 × 10−10 M), compared with those of other JH-inducible genes (29, 32, 33). The JH titer in the hemolymph of third- and fourth-instar B. mori larvae is maintained between 1.45–11.6 ng/mL (4.9–39.4 × 10−9 M) (21). The high sensitivity of BmKr-h1 to JH accounts for the expression of this gene at the nanomolar levels of endogenous JH during the early larval stages.

Because BmKr-h1 showed a rapid and extensive response to JH, the presence of a JHRE in the upstream and/or intronic regions of the gene was expected. We succeeded in identifying the −2165 to −2025 region as the kJHRE. Moreover, the results of mutation experiments indicated that the −2079GGCCTCCACGTG sequence (kJHREc) was indispensable for the JH response. A JHRE also has been identified in jhp21 of Locusta migratoria (38), the JH esterase gene of Choristoneura fumiferana (39), the early trypsin gene of A. aegypti (17), and several JH-inducible genes in A. mellifera and D. melanogaster (40). However, kJHREc was distinct from the previously reported JHREs in that it contained a palindromic canonical E-box sequence (CACGTG), to which bHLH transcription factors bind (26).

Ectopic expression of Gal4DBD–BmMet2 in HEK293 cells led to the induction of the UAS reporter by JH. Furthermore, the dose–response relationships of the tested compounds were comparable to those observed in the induction of the BmKr-h1 transcript in NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells. Given that JHs are insect-specific hormones (41), factors involved in the JH signaling pathway, including the JH receptor, are not likely to be present in mammalian cells. Therefore, it is a reasonable interpretation that BmMet2 accepts JH as a ligand and thereby gains the ability to increase transcription of a gene downstream of the interacting site. However, ectopic expression of native BmMet2 in HEK293 cells induced kJHRE reporter activity only weakly, and the induction was less sequence specific. This result suggested that additional cofactors, intrinsic to insect cells, also are required for the strict recognition or interaction of BmMet2 with the kJHRE sequence to induce strong JH-dependent activation of the downstream gene.

In this regard, interaction between Met and SRC is particularly intriguing, because RNAi silencing of Met and SRC in an A. aegypti cell line decreased the magnitude of induction of Kr-h1 by JH (42). Furthermore, specific binding of JH to the PASB domain of Tribolium Met induces dissociation of the Met–Met complex that forms in the absence of JH, and the JH-liganded Met specifically interacts with Tribolium Taiman (SRC) (18). In the present study, we confirmed that ectopic coexpression of BmMet2 and BmSRC in HEK293 cells resulted in increased activity of the kJHRE reporter by JH and that the interaction between BmMet2 and BmSRC was caused by the presence of JH. Collectively, we propose the following mechanism of JH-mediated induction of BmKr-h1: BmMet2 accepts JH as a ligand, JH-liganded BmMet2 interacts with BmSRC, and the JH/BmMet2/BmSRC complex activates BmKr-h1 by interacting with kJHRE (Fig. 4F). At present, however, the proposed mechanism remains hypothetical, because we have not demonstrated the binding of BmMet2/BmSRC complex to kJHRE.

Regarding the involvement of factors other than SRC in the specific induction of Kr-h1, coexpression of BmMet2 with several proteins that were considered as possible JH receptors or cofactors (i.e., BmMet1, BmUSP, BmARNT, BmHIF-1α, and BmTimeless) did not increase the JH-dependent reporter activity significantly in HEK293 cells. However, this result does not exclude the involvement of these or other unknown factors in the JH/BmMet2/SRC-mediated induction of Kr-h1. The complete picture of the complex that binds to kJHRE remains to be elucidated (Fig. 4F).

In conclusion, we have identified a JHRE in BmKr-h1 (kJHRE) and proposed a transcriptional mechanism of JH-mediated induction of BmKr-h1 that involves at least BmMet2, BmSRC, and kJHRE. Because kJHREc and Met/SRC are conserved in other insect species, this mechanism seems to be common in insects. Reporter assays using kJHRE and/or BmMet2 provide a sensitive and efficient screening system for JH agonists and antagonists and may be useful for generating data to develop biorational insecticides (41).

Materials and Methods

A detailed description of the materials and methods used in this study is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

cDNA Cloning.

A full-length cDNA library, constructed from the CA–CC complex of B. mori, was searched for the B. mori homologs of Kr-h1, Met, and SRC. This screen identified full-length cDNAs encoding two isoforms of BmKr-h1. Because the Met and SRC homologs were not found in this library, the whole-genome database for B. mori was searched using the tblastn program (http://kaikoblast.dna.affrc.go.jp/) with the sequences of T. castaneum Met and SRC as the query. Two genomic sequences, BmMet1 and BmMet2, encoding predicted proteins with homology to T. castaneum Met, were identified. Similarly, one genomic sequence encoding an SRC homolog (BmSRC) was identified. The full-length cDNA sequences of BmMet1, BmMet2, and BmSRC were obtained by RT-PCR and RACE using primers listed in Table S1, and the full ORFs were subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy plasmid (Promega).

Expression Analysis of BmKr-h1 in B. mori Cells.

To examine temporal changes in the expression of BmKr-h1, 1 × 105 NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells were seeded in 1 mL IPL-41 medium (Gibco, Invitrogen) containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Cell Culture Technologies) in a glass culture tube (12 × 75 mm) (Iwaki) coated with polyethylene glycol 20,000 (PEG) (Wako) and were incubated for 3 d before JHA treatment. The medium then was replaced with fresh medium containing 10 μM JHA, and the cells were cultured for 30 min to 24 h before collection for RNA extraction.

To examine the dose–response relationship, 1.5 × 105 cells in 200 μL medium were seeded into wells of a 96-well plate coated with PEG and were incubated for 24 h before JH treatment. The medium was replaced with fresh medium containing JH (JH I, JH II, or JH III), JHA, or a related compound (FA or MF) and incubated for 2 h at 25 °C before harvesting for RNA extraction.

The role of protein synthesis in the induction of BmKr-h1 by JH was examined by using CHX. First, 1.5 × 105 cells were seeded into wells of a 96-well plate for 24 h and were precultured in 100 μL medium with 50 μM CHX or solvent (DMSO) for 1 h. Then fresh medium containing 2 μM JHA (100 μL) was added (final concentration of JHA, 1 μM), and the cells were incubated for 2 h at 25 °C before collection for RNA extraction.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed essentially as described previously (43). The primers used for qPCR are listed in Table S2.

Construction of Reporter Plasmids.

The 5′-flanking and first intron regions of BmKr-h1 were amplified from B. mori genomic DNA by PCR and subcloned into the pGL4.14 luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega). Reporter plasmids carrying deleted and mutated 5′-flanking regions of BmKr-h1 were constructed from the pGL4.14_−4741/+116 and pGL4.14_−2165/+116 plasmids, respectively, by inverse PCR. Reporter plasmids carrying deleted basal BmKr-h1-promoter regions, the BmA3 promoter, the Bmhsp70 promoter, or 3× kJHREc were constructed by modifying the pGL4.14_−2165/+116 & −49/+116 plasmid. The primers used for the construction of the reporter plasmids are listed in Tables S3 and S4.

Construction of Expression Plasmids.

Plasmids for expressing BmMet1, BmMet2, BmSRC, VP16 fused with GAL4DBD, and VP16AD in HEK293 cells were constructed with the pBIND or pACT vector (Promega). Plasmids for expressing native BmMet2 and BmSRC in HEK293 cells were constructed by deleting GAL4DBD from the pBIND_GAL4DBD_BmMet2 plasmid and pBIND_GAL4DBD_BmSRC by inverse PCR. Plasmids for expressing native BmMet1, BmUSP, BmARNT, BmHIF-1α, and BmTimeless were constructed using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). The full ORFs of these cDNAs were amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pcDNA3.2/V5-DEST vector (Invitrogen). The primers used for the construction of the expression plasmids are listed in Table S1.

Transfection and Reporter Assays.

NIAS-Bm-aff3 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well in 200 μL medium in a 96-well plate (Iwaki) 1 d before transfection, and HEK293 cells were seeded at a density of 0.2 × 105 cells per well 2 d before transfection. Transfection of NIAS-Bm-aff3 and HEK293 cells was performed by using the Transfast transfection reagent (Promega) and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively. The pIZT_RLuc vector containing the Renilla luciferase gene was constructed as the reference for insect cells (44), and the pRL-TK vector (Promega) was used as the reference for mammalian cells. The cells were incubated for 24 h after transfection and treated with JH for 1 d. Then they were processed by using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions and were analyzed with a luminometer (ARVO; PerkinElmer).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Toshinori Kozaki for advice on cell culture techniques and Dr. Isao Kobayashi for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The nucleotide sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan/European Molecular Biology Laboratory Nucleotide Sequence Database/GenBank (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank) databases [accession nos. AB360766 (BmKr-h1α), AB642242 (BmKr-h1β), AB359911 (BmMet1), AB359912 (BmMet2), and AB703620 (BmSRC)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1204951109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Riddiford LM. Cellular and molecular actions of juvenile hormone I. General considerations and premetamorphic actions. Adv Insect Physiol. 1994;24:213–274. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt GR, Davey KG. Cellular and molecular actions of juvenile hormone. II. Roles of juvenile hormone in adult insects. Adv Insect Physiol. 1996;26:1–155. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert LI, Granger NA, Roe RM. The juvenile hormones: Historical facts and speculations on future research directions. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:617–644. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubrovsky EB. Hormonal cross talk in insect development. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakagawa Y, Henrich VC. Arthropod nuclear receptors and their role in molting. FEBS J. 2009;276:6128–6157. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riddiford LM. Juvenile hormone action: A 2007 perspective. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson TG, Fabian J. A Drosophila melanogaster mutant resistant to a chemical analog of juvenile hormone. Dev Biol. 1986;118:190–201. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashok M, Turner C, Wilson TG. Insect juvenile hormone resistance gene homology with the bHLH-PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2761–2766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miura K, Oda M, Makita S, Chinzei Y. Characterization of the Drosophila Methoprene -tolerant gene product. Juvenile hormone binding and ligand-dependent gene regulation. FEBS J. 2005;272:1169–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konopova B, Jindra M. Juvenile hormone resistance gene Methoprene-tolerant controls entry into metamorphosis in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10488–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703719104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parthasarathy R, Tan A, Palli SR. bHLH-PAS family transcription factor methoprene-tolerant plays a key role in JH action in preventing the premature development of adult structures during larval-pupal metamorphosis. Mech Dev. 2008;125:601–616. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furness SGB, Lees MJ, Whitelaw ML. The dioxin (aryl hydrocarbon) receptor as a model for adaptive responses of bHLH/PAS transcription factors. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3616–3625. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partch CL, Gardner KH. Coactivator recruitment: a new role for PAS domains in transcriptional regulation by the bHLH-PAS family. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:553–557. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godlewski J, Wang SL, Wilson TG. Interaction of bHLH-PAS proteins involved in juvenile hormone reception in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumann A, Barry J, Wang SL, Fujiwara Y, Wilson TG. Paralogous genes involved in juvenile hormone action in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2010;185:1327–1336. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.116962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, et al. Juvenile hormone counteracts the bHLH-PAS transcription factors MET and GCE to prevent caspase-dependent programmed cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2009;136:2015–2025. doi: 10.1242/dev.033712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Mead EA, Zhu J. Heterodimer of two bHLH-PAS proteins mediates juvenile hormone-induced gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:638–643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013914108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charles J-P, et al. Ligand-binding properties of a juvenile hormone receptor, Methoprene-tolerant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21128–21133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116123109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minakuchi C, Zhou X, Riddiford LM. Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) mediates juvenile hormone action during metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. Mech Dev. 2008;125:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minakuchi C, Namiki T, Shinoda T. Krüppel homolog 1, an early juvenile hormone-response gene downstream of Methoprene-tolerant, mediates its anti-metamorphic action in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev Biol. 2009;325:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakurai S, Niimi S. Development changes in juvenile hormone and juvenile hormone acid titers in the hemolymph and in-vitro juvenile hormone synthesis by corpora allata of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Insect Physiol. 1997;43:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konopova B, Smykal V, Jindra M. Common and distinct roles of juvenile hormone signaling genes in metamorphosis of holometabolous and hemimetabolous insects. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lozano J, Belles X. Conserved repressive function of Krüppel homolog 1 on insect metamorphosis in hemimetabolous and holometabolous species. Sci Rep. 2011;1:163. doi: 10.1038/srep00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imanishi S, Akiduki G, Haga A. Novel insect primary culture method by using newly developed media and extra cellular matrix. In vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2002;38:16-A. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi T, et al. Calreticulin is transiently induced after immunogen treatment in the fat body of the silkworm Bombyx mori. J Insect Biotechnol Sericology. 2006;75:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: Regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Saleh DS, Wyatt GR. Juvenile hormone regulation of an insect gene: A specific transcription factor and a DNA response element. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;122:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(96)03884-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wroblewski VJ, Harshman LG, Hanzlik TN, Hammock BD. Regulation of juvenile hormone esterase gene expression in the tobacco budworm (Heliothis virescens) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;278:461–466. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng QL, et al. Spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) juvenile hormone esterase: Hormonal regulation, developmental expression and cDNA cloning. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;148:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyengar AR, Kunkel JG. Follicle cell calmodulin in Blattella germanica: Transcript accumulation during vitellogenesis is regulated by juvenile hormone. Dev Biol. 1995;170:314–320. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comas D, Piulachs MD, Bellés X. Fast induction of vitellogenin gene expression by juvenile hormone III in the cockroach Blattella germanica (L.) (Dictyoptera, Blattellidae) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29:821–827. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Lindholm JR, Willis DK, Orth A, Goodman WG. Juvenile hormone regulation of Drosophila Epac—a guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;305:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubrovsky EB, Dubrovskaya VA, Berger EM. Hormonal regulation and functional role of Drosophila E75A orphan nuclear receptor in the juvenile hormone signaling pathway. Dev Biol. 2004;268:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirai M, Yuda M, Shinoda T, Chinzei Y. Identification and cDNA cloning of novel juvenile hormone responsive genes from fat body of the bean bug, Riptortus clavatus by mRNA differential display. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubrovsky EB, Dubrovskaya VA, Bilderback AL, Berger EM. The isolation of two juvenile hormone-inducible genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2000;224:486–495. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parthasarathy R, et al. Juvenile hormone regulation of male accessory gland activity in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Mech Dev. 2009;126:563–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu JS, Busche JM, Zhang X. Identification of juvenile hormone target genes in the adult female mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou S, et al. A locust DNA-binding protein involved in gene regulation by juvenile hormone. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;190:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kethidi DR, et al. Identification and characterization of a juvenile hormone (JH) response region in the JH esterase gene from the spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19634–19642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311647200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li YP, Zhang ZL, Robinson GE, Palli SR. Identification and characterization of a juvenile hormone response element and its binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37605–37617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704595200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minakuchi C, Riddiford LM. Insect juvenile hormone action as a potential target of pest management. J Pestic Sci. 2006;31:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Xu J, Sheng Z, Sui Y, Palli SR. Steroid receptor co-activator is required for juvenile hormone signal transduction through a bHLH-PAS transcription factor, methoprene tolerant. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8437–8447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shinoda T, Itoyama K. Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase: A key regulatory enzyme for insect metamorphosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11986–11991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanamori Y, et al. A eukaryotic (insect) tricistronic mRNA encodes three proteins selected by context-dependent scanning. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36933–36944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.