Abstract

The prevalence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is higher in patients with type 2 diabetes, a disorder characterized by hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance. The role of hyperinsulinemia as an independent participant in the atherogenic process has been controversial. In the current study, we tested the effect of insulin and the insulin sensitizer, adiponectin on human macrophage foam cell formation. We found that both insulin and adiponectin increased expression of the type 2 scavenger receptor CD36 by ~2 fold and decreased expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1 by more than 80%. In both cases regulation was post-transcriptional. As a consequence of these changes, we found that oxidized LDL (oxLDL) uptake was increased by 80% and cholesterol efflux to apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) was decreased by ~25%. This led to 2–3 fold more cholesterol accumulation over a 16 hour period. As reported previously in studies of murine systems, scavenger receptor-A (SR-A) expression on human macrophages was down-regulated by insulin and adiponectin. Insulin and adiponectin did not affect oxLDL induced secretion of monocyte attractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These studies suggest that hyperinsulinemia could promote macrophage foam cell formation and thus may contribute to atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: insulin, atherosclerosis, macrophage, foam cell, CD36, ABCA1

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in many developed countries and atherosclerosis accounts for most of the major pathology1,2. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, a condition characterized by insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia, have a 2–3 fold increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease3–5. While there have been many studies that support the causative role of insulin resistance in cardiovascular disease from both epidemiologic and experimental perspectives6–11, there is very little evidence supporting a direct cause and effect relationship between hyperinsulinemia and atherosclerosis. Furthermore, the role of hyperinsulinemia as an independent risk factor has been controversial. Several prospective population studies including the Quebec Cardiovascular study showed an association of high plasma insulin levels with increased risk of coronary heart disease12–17, but other studies, such as that of Welin and colleagues failed to show such an association18,19. Since hyperinsulinemia usually occurs in states of insulin resistance it is difficult to determine an independent role for hyperinsulinemia in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

Excessive lipid accumulation by macrophages plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. Lipid laden macrophage foam cells accumulate in atheromatous plaque and promote inflammation by secreting cytokines that recruit other immune cells to the arterial intima. Foam cells are generated by uncontrolled uptake of modified LDL, especially oxidized LDL (oxLDL), and/or impaired cholesterol efflux20,21. Lipid homeostasis in macrophages is regulated by scavenger receptors, including CD36 and scavenger receptor-A (SR-A), that mediate uptake and specific ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family transporters that mediate cholesterol efflux to apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) and high density lipoprotein (HDL)22–25. Thus, alteration in expression of these molecules in macrophages may affect foam cell formation and progression of atherosclerosis.

Adiponectin, also known as Acrp30, is an adipokine exclusively expressed and secreted by adipocytes that functions as an insulin sensitizer. Plasma concentrations of adiponectin are low in type 2 diabetic patients26,27 and mice lacking adiponectin have hepatic insulin resistance 28. Administration of adiponectin improves insulin sensitivity in animal models of type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance29,30. The precise molecular mechanism by which adiponectin sensitizes cells to insulin signals has not been elucidated, however, it appears to include cross-talk between adiponectin and insulin receptor signaling pathways31. Adiponectin was recently suggested to have an anti-atherogenic effect through regulation of SR-A and acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-1 (ACAT-1) expression in macrophages32,33.

In the current study we used human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages to test the effect of insulin and adiponectin on macrophage expression of scavenger receptors and ATP-binding cassette transporter sub-family A member 1 (ABCA1) and on oxLDL uptake, cholesterol efflux and foam cell formation. We found that insulin and adiponectin up-regulated CD36 expression and down-regulated ABCA1 expression, resulting in enhanced oxLDL uptake, diminished cholesterol efflux and increased foam cell formation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

LDL prepared from human plasma was oxidatively modified as previously described using a myeloperoxidase, glucose oxidase, nitrite system34. Bovine insulin was from Sigma and recombinant human adiponectin from R&D systems. Polyclonal antibody against human CD36 was from Cayman Chemical. Monoclonal anti-human CD36 IgG, phycoerythrin- conjugated anti-CD36 IgG, and antibodies against SR-A, actin, and α-tubulin were from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against ABCA-1 and EMR1(F4/80) were purchased from Abcam. C14-labeled cholesterol was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. ApoA1 protein was prepared as previously described35. Quantikine® Colorimetric Sandwich ELISA kits for IL-6 and MCP-1 were from R&D systems.

Cells

Human monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation and were cultured in RPMI containing human AB serum (10%) for 7 days to allow for macrophage differentiation. The differentiation of the monocytes into macrophages was confirmed by flow cytometry with anti- EMR1(F4/80) antibody. Human peripheral blood was donated by non-diabetic healthy volunteers. Each sample was screened and the absence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was confirmed.

Immunoblot Analyses

Human macrophages incubated with different concentrations of insulin (300pM, 2nM, 100nM), adiponectin (2μg/ml), oxLDL (50μg/ml), LY294002 (10μM) or wartmannin (100nM) for 16 hours were lysed with buffer containing 1% triton X-100. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), and probed with antibodies against CD36, ABCA-1, SR-A, actin, or α-tubulin. Band intensities were quantified by ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics) and Gel-Pro Analyzer (MediaCybernetics).

Flow cytometry

Human macrophages plated on serum-coated glass coverslips were incubated with insulin, adiponectin, or oxLDL for 16h, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Treated macrophages were gently scraped and collected in microtubes and then stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD36 or anti-SR-A IgG prior to measuring flourescence intensity by flow cytometry with a Becton-Dickinson FACScan. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star). To assess oxLDL uptake oxLDL was labeled with the fluorescent probe 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanide perchlorate (diI; Molecular Probes) as previously described36. Macrophages pre-incubated as above with insulin or adiponectin for 16h were then exposed to diI-oxLDL (10μg/ml) for 20min and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by laser confocal microscopy. Fluorescence uptake was quantified using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by Tri reagent from human macrophages treated with insulin, adiponectin, or oxLDL for 16h and was converted into cDNA by reverse transcriptase (Roche) with oligo-dT primer. cDNAs were then used for PCR with the primers 5′-CAG AGG CTG ACA ACT TCA CAG-3′, 5′-AGG GTA CGG AAC CAA ACT CAA-3′ for CD36 or the primers 5′-AAC TCT ACA TCT CCC TT CCC G -3′, 5′-TGT CCT CAT ACC AGT TGA GAG AC-3′ for ABCA-1. PCR for actin was used as a reference with the primers 5′-GTG GGG CGC CCC AGG CAC CA-3′, 5′-CTC CTT AAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC-3′. PCR amplification was 22 cycles of 94°C for 1minute, 56°C for 1 minute, 72°C for 2 minutes for CD36, 28 cycles for ABCA-1, and 17 cycles for actin.

Cholesterol Efflux Assay

Macrophages plated on 24 well dishes were treated with insulin (2nM, 100nM) or adiponectin (2μg/ml) with or without wartmannin (100nM) for 16 hours. OxLDL (50μg/ml) was incubated with C14- labeled cholesterol (0.2μCi/ml) at 37°C for 30 minutes and then loaded onto the macrophages. After 6 hours, C14-cholesterol-labeled cells were washed with PBS and incubated with RPMI 1640 medium for 16 hours. C14-cholesterol released from the cells into the medium was measured using scintillation counter. Cellular cholesterol was extracted by hexane:isopropanol (3:2 v/v) and C14 radioactivity in the extract solution was measured by scintillation counter. Efflux percentage was calculated as C14 radioactivity in medium/(C14 radioactivity in medium + C14 radioactivity in cells) × 100%.

Intracellular cholesterol measurement

Human macrophages plated in 6 well dish were incubated with insulin (2nM, 100nM) or adiponectin (2μg/ml) with or without LY294002 (10μM). The cells were treated with oxLDL for 16 hours and lysed by 0.5% triton X-100 containing buffer on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 17,000g for 30min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for cholesterol measurement. Cholesterol was measured by using Cayman cholesterol assay kit (Cayman chemical). Briefly, the cell lysates were mixed with assay buffer containing cholesterol esterase, cholesterol oxidase, HRP and ADHP (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine). Fluorescent product resorufin which was generated by the reaction between ADHP and hydrogen peroxide from cholesterol oxidation could be measured by fluorescence plate reader using excitation wavelengths of 530–580 nm and emission wavelengths of 585–595 nm. We also measured total cholesterol and free cholesterol of macrophages by using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Human macrophages were incubated with insulin (2nM, 100nM) or adiponectin (2μg/ml) with or without wartmannin (200nM) and then treated with oxLDL (50μg/ml) for 16 hours. These cells were resuspended with 900μl water and 100μl of 1μg/ml coprosternol in isopropanol and applied to the GC-MS as described previously37. We recorded the total ion mass spectra of trimethylsilyl(TMS) derivatives, extracted the GC chromatograms and calculated cholesterol content in each samples. The intracellular cholestserol of each sample was normalized by protein concentration of each sample.

Results

Insulin and adiponectin alter scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages

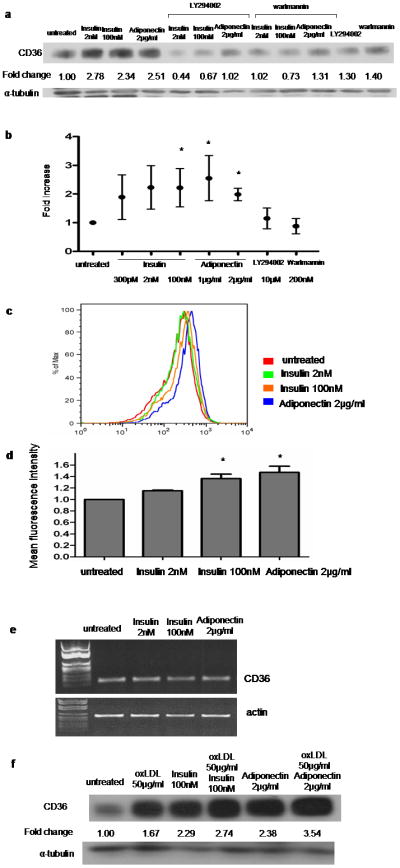

Immunoblots for CD36 showed that insulin at 2 and 100nM and adiponectin at 2μg/ml increased CD36 expression in macrophages. The adiponectin concentration used was one that increased phosphorylation of Akt Ser473 to the same extent as did 100nM insulin (data not shown). The increase in CD36 was prevented by pre-treatment of the cells with the PI3-kinase inhibitors LY294002 or wartmannin (Figure 1a). The inhibitors themselves had no effect (Fig 1a), unlike what was previously reported for murine macrophages38. Although the magnitude of effect on CD36 expression induced by insulin or adiponectin varied among cells from different donors, cumulative data from 15 different subjects showed a mean increase of 2 fold (Figure 1b; p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Insulin and adiponectin increase CD36 expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages.

(a) Macrophages were pretreated with indicated concentrations of insulin or adiponectin for 16h and then lysed and assessed by western blot for CD36 expression. In some cases cells were also treated with LY294002 (10μM) or wartmannin (100nM). Blots were stripped and re-probed with anti-tubulin antibody and fold change in CD36 band density was determined from scanned images. Image is representative of n=15. (b) Means ± SD of data from 15 different donors normalized as in panel (a); * P<0.05. (c) Flow cytometry histogram of cells treated with insulin or adiponectin and then stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD36 IgG. (d) Mean fluorescence intensity was assessed by flow cytometry as described in (c). The bar graph of comparison was generated from experiments using macrophages from 5 different subjects; * P<0.001. (e) mRNA isolated from cells treated with insulin or adiponectin was assessed by RT-PCR using specific primers for CD36 and actin. (f) Macrophages pretreated with insulin or adiponectin along with or without oxLDL, were assessed by western blot for CD36 expression as described in (a).

Using flow cytometry we showed that the increase in total CD36 protein levels induced by insulin or adiponectin were associated with a significant, dose-dependent increase in macrophage cell surface CD36 expression (Figure 1c). Cumulative data from 5 different subjects showed that 100nM of insulin and 2μg/ml of adiponectin induced mean increases of 1.36 fold and 1.47 fold, respectively (Figure 1d; p<0.001). CD36 mRNA levels measured by RT-PCR did not change after macrophages were exposed to insulin or adiponectin (Figure 1e), suggesting that CD36 regulation was post-transcriptional. OxLDL known to up-regulate CD3639,40, had additive effect in CD36 increase when combined with insulin or adiponectin (Figure 1f).

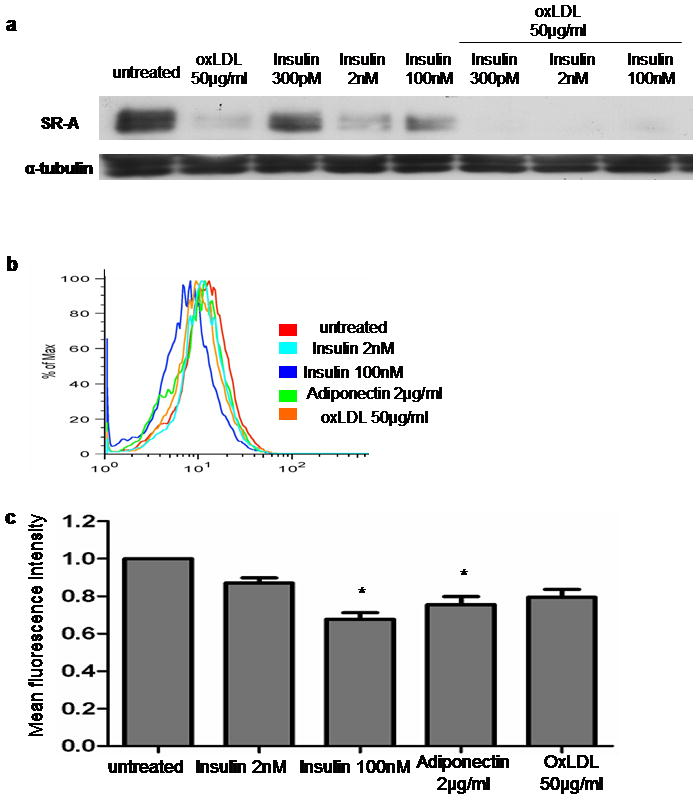

SR-A, the other major scavenger receptor on macrophages for modified LDL41, was also regulated by insulin, but in the opposite direction to CD36. Immunoblots revealed that insulin induced a dramatic, dose-dependent decrease in expression of SR-A (Figure 2a). Immunofluorescence flow cytometry showed that insulin down-regulated SR-A surface expression and that adiponectin also down-regulated SR-A expression (Figure 2b and 2c). Interestingly, oxLDL which is known to up-regulate CD3639,40, decreased expression of SR-A in human monocyte-derived macrophages (Figures 2a, 2b and 2c) and had additive effect when combined with insulin (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Insulin and adiponectin decrease expression of SR-A in human monocyte-derived macrophages.

Macrophages were pretreated with insulin, adiponectin, oxLDL, or insulin plus oxLDL for 16h and analyzed by immunoblot (a) or flow cytometry (b) as in Figure 1 using a monoclonal antibody specific for SR-A. (a),(b); Experiments were repeated with macrophages from 3 different donors, respectively. (c) Mean fluorescence intensity was assessed by flow cytometry in (b). The bar graph of comparison was generated from experiments using macrophages from 3 different subjects; * P<0.05.

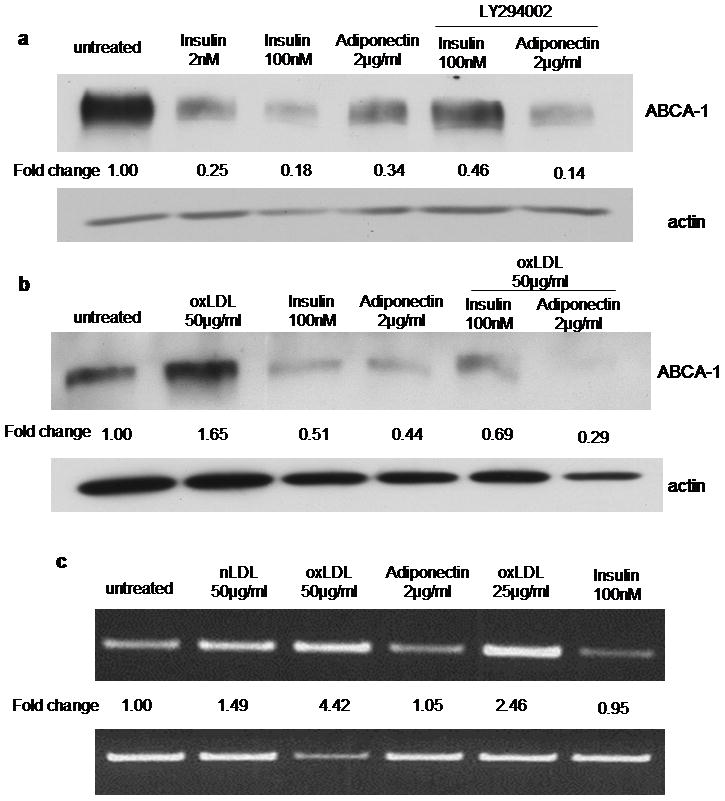

Insulin and adiponectin decrease ABCA-1 expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages

Immunoblots for the cholesterol transporter ABCA-1 revealed that insulin and adiponectin decreased ABCA-1 expression in macrophages by up to 80% (Figure 3a). Interestingly, PI3-kinase inhibition by LY294002 had no effect on adiponectin-mediated down-regulation and only a partial effect on insulin (Figure 3a). Insulin and adiponectin also induced down-regulation of ABCA-1 in the presence of oxLDL (Fig. 3b), which by itself has been shown to increase ABCA-1 expression42. These data suggest that the regulatory mechanism of insulin and adiponectin on ABCA-1 expression may be distinct from the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor (LXR/RXR) regulatory pathway activated by oxLDL42. This is further supported by analysis of mRNA levels (Figure 3c) which showed no change in ABCA-1 levels after macrophages were exposed to insulin or adiponectin, in contrast to the 4.4 fold increase seen after exposure to oxLDL.

Figure 3. Insulin and adiponectin decrease ABCA-1 expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages.

(a) Macrophages were pretreated for 16h with insulin or adiponectin in the presence or absence of LY294002 (10μM) and then lysed and analyzed by immunoblot for ABCA-1 expression. Blots were stripped and re-probed with anti-actin antibody and fold change in ABCA-1 band density was determined from scanned images. Image is representative of 3 repeatative bltos.. (b) Cells were exposed to oxLDL (50μg/ml) with or without insulin or adiponectin and analyzed as in panel a. (c) RT-PCR for ABCA-1 mRNA of macrophages treated as described in (b).

Insulin and adiponectin enhance oxLDL-induced lipid accumulation in human monocyte-derived macrophages

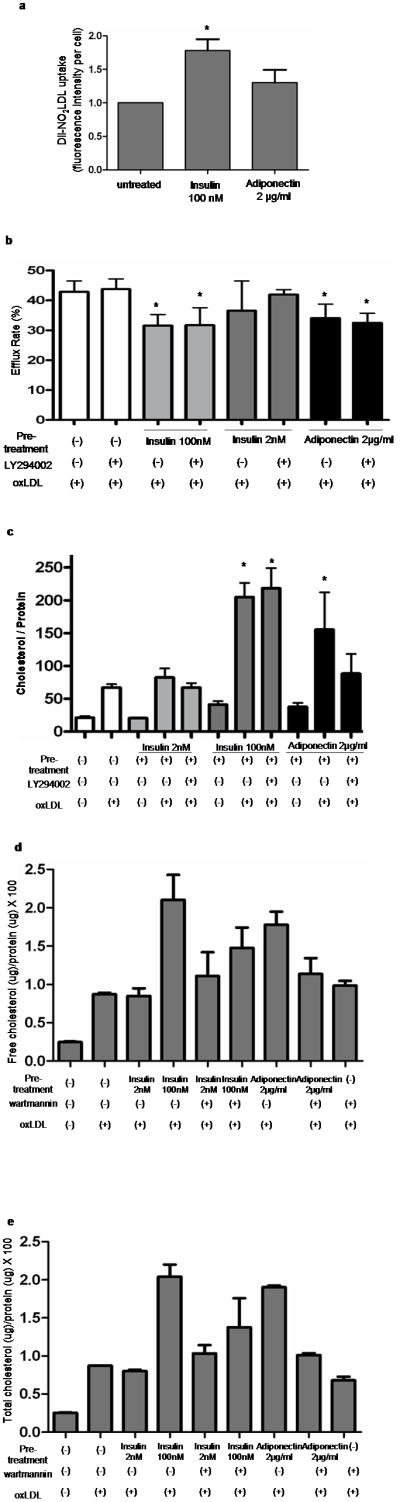

Having shown that insulin and adiponectin increased expression of CD36 and decreased expression of ABCA-1 in human macrophages, we next examined their effect on oxLDL uptake, cholesterol efflux and foam cell formation. To assess oxLDL uptake we added diI-labeled oxLDL to macrophages that had been exposed to insulin (100nM) or adiponectin (2μg/ml) for 16 hours and then measured intracellular fluorescence after 20 minutes using confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 4a, insulin increased uptake by ~80% (p < 0.05) while adiponectin had no effect (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Insulin and adiponectin enhance oxLDL mediated cholesterol loading of human mononcyte-derived macrophages.

(a) Macrophages were pretreated with insulin (100nM) or adiponectin (2μg/ml) for 16h and then exposed to DiI-labeled oxLDL for 20min at 37°C. Fluorescence uptake was quantified by digital confocal microscopy using Imge-Pro software. The graph represents mean ± SD of 5 experiments analyzing 50–100 cells each (* P<0.05). (b) Macrophages were pre-treated with insulin or adiponectin for 16 hours and then exposed to oxLDL containing C14-labeled cholesterol for 6 hours. C14-labeled cholesterol effluxed to apoA1 was measured by scintillation counting. The graph shows mean ± SD from separate assays using macrophages from 3 different donors (* P<0.05). (c) Macrophages were pretreated with insulin or adiponectin as above and then exposed to oxLDL (50μg/ml) for 16h at 37°C. Intracellular cholesterol was measured by the cholesterol oxidation reaction method. The graph shows mean ± SD from experiments using macrophages from 3 different donors. (* P<0.001) (d)(e); Macrophages pretreated with insulin or adiponectin were exposed to oxLDL (50μg/ml). Free (d) or total (e) cholesterol was measured by gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

To evaluate the effect of insulin and adiponectin on cholesterol efflux from macrophages we loaded cells with oxLDL containing C14-labeled cholesterol and then measured the rate of C14 efflux to apoA1 in the culture medium. Pre-treatment with either insulin or adiponectin decreased efflux by ~25% (Figure 4b; p< 0.05).

We hypothesized that the increased macrophage uptake of oxLDL and impaired cholesterol efflux induced by insulin or adiponectin would result in intracellular accumulation of excessive lipoprotein derived cholesterol and ultimately in foam cell formation43. Figure 4c shows that after 16h of cell exposure to oxLDL, intracellular cholesterol content measured by enzymatic cholesterol assay was increased by 3 fold in macrophages pre-treated with insulin or adiponectin, compared to untreated cells. Total cholesterol and free cholesterol of macrophages measured by GC-MS also showed that free and total intracellular cholesterol of macrophages were increased by pre-treatment with insulin or adiponectin (Figure 4d and 4e).

OxLDL is known to induce secretion of cytokines such as MCP-1 and IL-6 from mouse macrophages44. Here we show that oxLDL also increased secretion of IL-6 and MCP-1 from human monocyte-derived macrophages (Supplementary Figure 1), but that neither insulin nor adiponectin affected baseline or oxLDL induced cytokine secretion.

Discussion

Hyperinsulinemia was first suggested as a risk factor for atherosclerosis more than 30 years ago, based on the observation that insulin levels are higher than normal in patients with ischemic heart disease45. Since then, there have been many clinical and experimental studies revealing that high levels of insulin precede development of arterial diseases in diabetic and non-diabetic patients12–17, 46–48. However, the role of hyperinsulinemia as an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic coronary disease has been controversial. Mostly, hyperinsulinemia occurs with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and is regarded as a compensatory mechanism of insulin resistance. Many studies suggest insulin resistance as a risk factor for atherosclerosis based on its pathologic effects on dyslipidemia, hypertension, and a hypercoagulable state, which accelerate atherosclerosis6–11,49. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the link between hyperinsulinemia and atherosclerosis is causative, and this compels more experimental studies.

Macrophages perform a crucial role in the atherogenic process by generating lipid laden foam cells20. Macrophages are known to express most insulin signaling molecules except insulin receptor substrate 1(IRS1) and glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT-4)50,51. Even though insulin activates the insulin receptor (IR)/IRS2/PI3K/Akt pathway in macrophages as in other types of insulin-responsive cells, there have been few studies investigating the biological functions of insulin signaling in macrophages. In the current study, we evaluated if insulin affects macrophage foam cell formation and found that insulin increased expression of CD36 and decreased ABCA-1, which may promote cholesterol accumulation in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Although the mechanism is not clear, the insulin-mediated regulatory mechanism of CD36 and ABCA-1 appear to be post-transcriptional based on our results from RT-PCR. A recent study showing that insulin increased CD36 expression in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) or HEK 293 cells via regulating CD36 turnover52 supports our observation and permits a possible expectation that a similar regulatory pathway may be activated in macrophages. The mechanisms of insulin regulation of CD36 and ABCA-1 need to be studied and it appears to be that these proteins are regulated via different pathways.

Adiponectin is known to enhance insulin sensitivity, however, the signaling mechanism by which adiponectin sensitizes insulin is not clear. In our study, adiponectin showed an overlapping signaling with insulin. Low concentration of adiponectin increased phosphorylation of Akt (Ser436) by the same degree as insulin and had the same modulating effect on CD36 and ABCA-1 as insulin (Fig. 1 and 3). Previous studies showed that adiponectin had an anti-atherogenic property in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice53 and one of the suggested mechanisms was an inhibitory effect of adiponectin on SR-A expression and acetylated LDL uptake54. In our current study, we reproduced the previous finding and showed that both insulin and adiponectin decreased SR-A expression in macrophages. However, the net effect of adiponectin resulted in increased intracellular cholesterol accumulation, which was opposite of previous reports. In addition to SR-A, adiponectin is known to down-regulates acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase-1 (ACAT-1) that catalyzes cholesteryl ester (CE) formation33 and therefore, adiponectin treatment decreased acetylated LDL-induced CE accumulation in macrophages33, 55. These intriguing results may be due to the different sources of cholesterol for lipid uptake assays, different concentrations of adiponectin, and different modes of adiponectin activities. In our study using MPO-modified LDL (oxLDL) which is known to be a specific ligand for CD3656, adiponectin increased uptake of oxLDL via increased expression of CD36, while in the previous studies performed with acetylated LDL (acLDL), a specific ligand for SR-A57, adiponectin decreased acLDL uptake via a decrease in SR-A. Therefore, the effect of adiponectin in vivo may be determined by the specificity of modified LDL for different scavenger receptors.

Changes in the protein levels of CD36 and ABCA-1 induced by insulin and adiponectin appear to be regulated by PI3-kinase. Our study showed that PI3-kinase inhibitor prevented the increase of CD36 expression induced by insulin and adiponectin (Fig. 1) while it minimally blocked the effect of these reagents on the expression of ABCA-1 (Fig. 3). The functional effect of PI3-kinase blockade on the intracellular cholesterol of macrophages was varied among macrophages from different donors (Fig. 4). As expected, based on the minimal blockade of ABCA-1 decrease, the PI-3 kinase inhibitor had no effect on cholesterol efflux of macrophages (Fig. 4b) but partially prevented the increase of intracellular cholesterol by blocking increased CD36 expression.

Atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes share similar pathologic mechanisms including elevation in cytokines like monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) which contribute to underlying inflammation of both58. OxLDL is abundant in both of these conditions and is known to induce secretion of these proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages 59. Previous studies have suggested anti-inflammatory activities of insulin by showing that insulin infusion to diabetic patients suppressed mononuclear cell expression of toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 and TLR-460. However, another study showed that prolonged exposure to insulin accentuated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induced transcription of pro-inflammatory genes while short term exposure inhibited the transcription61. In our current study, insulin and adiponectin, also known to have anti-inflammatory activity62, did not affect oxLDL-induced secretion of MCP-1 and IL-6 in macrophages.

In the current study, we propose evidence that insulin facilitates macrophage foam cell formation, although this is a topic of controversy. It is sometimes suggested that hyperinsulinemia in the presence of insulin resistance may not be metabolically effective, however, it is possible that one pathway may remain active when the other pathway is blocked by insulin resistance. Therefore, more studies are needed to show how insulin activates different pathways and may be involved in different biological functions specifically affected by insulin resistance. The risk of cardiovascular disease is 10 folds higher than normal in patients with type 1 diabetes63. Even though type 1 diabetes is characterized by impaired insulin secretion, it does not rule out the possible pathologic effect of hyperinsulinemia. Indeed, many patients with type 1 diabetes have hyperinsulinemia from excessive dose of insulin and resulting insulin resistance64. Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia appears to drive insulin resistance 65. Therefore, for the proper management of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, more investigation about the role of hyperinsulinemia is required.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that hyperinsulinemia may promote atherosclerosis by promoting macrophage foam cell formation in the setting of abundant oxLDL which has specific affinity to CD36.

Supplementary Material

Macrophages were pretreated with insulin or adiponectin and then cultured in the presence or absence of oxLDL (50μg/ml) for 16h. Post-culture media was collected and analyzed for IL-6 (a) or MCP-1 (b) by ELISA.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to David Schmitt, Dr. Xin-Min Li and Robert Koeth in Dr. Stanley Hazen’s laboratory in Cleveland Clinic for helping us perform the cholesterol efflux assay and GC-MS. This study was supported by NIH P01 HL087018 (RLS) and a KL2 award (SK) from the Case Western Reserve University Clinical Translational Research Award UL1RR024989.

Abbreviation

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter sub-family A member 1

- apoA1

apolipoprotein A1

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- MCP-1

monocyte attractant protein-1

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- oxLDL

oxidized LDL

- SR-A

scavenger receptor-A

- LXR

liver X receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

References

- 1.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors; Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and glucose tolerance as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. Diabetes Care. 1979;2:120–126. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pyörälä K, Laakso M, Uusitupa M. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: an epidemiologic view. Diabetes Metab Dev. 1987;3:463–524. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610030206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infacrion. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reaven GM. Banting lecture. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, et al. Insulin resistace, the metabolic syndrome, and incident cardiovascular events in the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 2005;54:3252–3257. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanley AJ, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance in relation to the incidence of cardiovascular disease: the San Antonio Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1177–1184. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeFronzo RA. Is insulin resistance atherogenic? Possible mechanisms. Atheroscler suppl. 2006;7:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonora E, Formentini G, Calcaterra F, et al. HOMA-estimated insulin resistance is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic subjects: prospective data from the Cerona Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1135–1141. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy KJ, Singh M, Bangit JR, et al. The role of insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an updated review. J Cardiovasc Med. 2010;11(9):633–647. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328333645a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyörälä K. Relationship of glucose tolerance and plasma insulin to the incidence of coronary heart disease: results from two population studies in Finland. Diabetes Care. 1979;2:131–141. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welborn TA, Wearne K. Coronary heart disease incidence and cardiovascular mortality in Busselton with reference to glucose and insulin concentrations. Diabetes Care. 1979;2(2):154–160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ducimetiere D, Eschwege E, Papoz L, et al. Relationship of plasma insulin levels to the incidence of myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease mortality in middle-aged population. Diabetologia. 1980;19:205–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00275270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyörälä K, Savolainen E, Kankola S, et al. Plasma insulin as coronary heart disease risk factor: relationship to other risk factors and predictive value during 9 ½ year follow-up of the Helsinki Policemne Study population. Acta Med Scand. 1985;701(suppl 1):38–52. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb08888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eschwege E, Richard JL, Thibault N, et al. Coronary heart disease mortality in relation with diabetes, blood glucose and plasma insulin levels. The Paris Prospective Sutdy, ten years later. Horm Metab Res. 1985;(suppl 15):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, et al. Hyperinsulinemia in a population at high risk for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:220–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welin L, Eriksson H, Larsson B, et al. Hyperinsulinemia is not a major coronary risk factor in elderly men. The study of men born in 1913. Diabetologia. 1992;35:766–770. doi: 10.1007/BF00429098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrara A, Barrett-Connor EL, Edelstein SL. Hyperinsulinemia does not increase the risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in elderly men or women without diabetes: the Rancho Bernardo Study, 1984–1991. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:857–869. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li AC, Glass CK. The macrophage foam cell as a target for therapeutic intervention. Nat Med. 2002;8:1235–1242. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleemann R, Zadelaar S, Kooistra T. Cytokines and atherosclerosis: a comprehensive review of studies in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:360–376. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Smith JD, et al. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1049–1056. doi: 10.1172/JCI9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Winther MP, Hofker MH. Scavenging new insights into atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1039–1041. doi: 10.1172/JCI9919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terpstra V, Kondratenko N, Steinberg D. Macrophages lacking scavenger receptor A show a decrease in binding and uptake of acetylated low-density lipoprotein and of apoptotic thymocytes, but not of oxidatively damaged red blood cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8127–8131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Eck M, Pennings M, Hoekstra M, et al. Scavenger receptor B1 and ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 in reverse choletsterol transport and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:307–315. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000169351.28019.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindsay RS, Funahashi T, Hanson RL, et al. Adiponectin and development of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indian population. Lancet. 2002;360:57–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deepa SS, Dong LQ. APPL1: role in adiponectin signaling and beyond. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(1):E22–E36. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90731.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawrocki AR, Rajala MW, Tomas E, et al. Mice Lacking Adiponectin Show Decreased Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity and Reduced Responsiveness to Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ Agonists. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2654–2660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotta K, Funahashi T, bodkin NL, et al. Circulating concentrations of the adipocyte protein adiponectin are decreased in parallel with reduced insulin sensitivity during the progression to type 2 diabetes in rhesus monkeys. Diabetes. 2001;50:1126–1133. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C, Mao X, Wang L, et al. Adiponectin Sensitizes Insulin Signaling by Reducing p70 S6 Kinase-mediated Serine Phosphorylation of IRS-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7991–7996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:1057–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furukawa K, Hori M, Ouchi N, et al. Adiponectin down-regulates acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-1 in cultured human monocyte-derived macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:831–836. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podrez EA, Schmitt D, Hoff HF, et al. Myeloperoxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species convert LDL into an atherogenic form in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(11):1547–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rye KA, Garrety KH, Barter PJ. Changes in the size of reconstituted high density lipoproteins during incubation with cholesteryl ester transfer protein: the role of apolipoproteins. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahaman SO, Lennon DJ, Febbraio M, et al. A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4(3):211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinet P, Wang Z, Hazen SL, et al. A simple and sensitive enzymatic method for cholesterol quantification in macrophages and foam cells. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(11):3364–3369. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D007336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang CP, Han S, Okamoto H, et al. Increased CD36 protein as a response to defective insulin signaling in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(5):764–773. doi: 10.1172/JCI19528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han J, Hajjar DP, Febbraio M, et al. Native and modified low density lipoproteins increase the functional expression of the macrophage class B scavenger receptor, CD36. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21654–21659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez J, et al. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ. Cell. 1998;93:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugano R, Yamamura T, Harada-Shiba M, et al. Uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein in a THP-1 cell line lacking scavenger receptor A. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158(2):351–7. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang CK, Yi GH, Yang JH, et al. Oxidized LDL upregulated ATP binding cassette transporter-1 in THP-1 macrophages. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25(5):581–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Relative roles of various efflux pathways in net cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells in atherosclerotic lesions. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21(5):441–53. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833dedaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janabi M, Yamashita S, Hirano K, et al. Oxidized LDL-induced NF-kappa B activation and subsequent expression of proinflammatory genes are defective in monocyte-derived macrophages from CD36-deficient patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(8):1953–60. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stout RW, Vallance-Owen J. Insulin and atheroma. Lancet. 1969;i:1078–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91711-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ronnemaa T, Laakso M, Pyorala K, et al. High fasting plasma insulin is an indicator of coronary heart disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients and nondiabetic subjects. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:80–90. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Standl E, Janka HU. High serum insulin concentrations in relation to other cardiovascular risk factors in macrovascular disease of type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 1985;15 (Suppl):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uusitupa MIJ, Niskanen LK, Siitonen O, et al. 5-year incidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease in relation to general risk factors, insulin level, and abnormalities in lipoprotein composition in non-insulin-dependent diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Circulation. 1990;82:27–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Plutzky J, Viberti G, Haffner S. Atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance: mechanistic links and therapeutic targets. J Diabetes Complications. 2002;16:401–415. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welham MJ, Bone H, Levings M, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-2 is the major 170-kDa protein phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to cytokines in murine lymphohemopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1377–1381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malide D, Davies-Hill TM, Levine M, et al. Distinct localization of GLUT-1, -3, and -5 in human monocyte-derived macrophages: effects of cell activation. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E516–E526. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.3.E516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith J, Su X, El-Maghrabi R, et al. Opposite regulation of CD36 ubiquitination by fatty acids and insulin: effects on fatty acid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(20):13578–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, et al. Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2767–2770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042707.50032.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:1057–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tian L, Luo N, Klein RL, et al. Adiponectin reduces lipid accumulation in macrophage foam cells. Atheroscler. 2009;202:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Podrez EA, Schmitt D, Hoff HF, et al. Myeloperoxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species convert LDL into an atherogenic form in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(11):1547–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldstein JL, Ho YK, Basu SK, et al. Binding site on macrophages that mediates uptake and degradation of acetylated low density lipoprotein, producing massive cholesterol deposition. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1979;76:333–337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernández-Real JM, Ricart W. Insulin Resistance and Chronic Cardiovascular Inflammatory Syndrome. Endocrine Reviews. 2003;24(3):278–301. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller YI, Viriyakosol S, Worrall DS, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent and – independent cytokine secretion induced by minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1213–1219. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159891.73193.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghanim H, Mohanty P, Deopurkar R, et al. Acute modulation of toll-like receptors by insulin. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1827–1831. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iwasaki Y, Nishiyama M, Taguchi T, et al. Insulin exhibits short-term anti-inflammatory but long-term proinflammatory effects in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;298(1–2):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohashi K, Parker JL, Ouchi N, et al. Adiponectin promotes macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6153–6160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, et al. Mortality from heart disease in a cohort of 23,000 patients with insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetologia. 2003;46(6):760–765. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Conway B, Costacou T, Orchard T. Is glycaemia or insulin dose the stronger risk factor for coronary artery disease in type 1 diabetes? Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2009;6(4):223–230. doi: 10.1177/1479164109336041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shanik MH, Xu Y, Skrha J, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care. 2008;31 (Suppl 2):S262–268. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Macrophages were pretreated with insulin or adiponectin and then cultured in the presence or absence of oxLDL (50μg/ml) for 16h. Post-culture media was collected and analyzed for IL-6 (a) or MCP-1 (b) by ELISA.