Abstract

In this review, we highlight the evolution of our knowledge about the way Mg2+ participates in the activation of heterotrimeric G proteins, beginning with its requirement in hormonal stimulation of fat cell adenylyl cyclase (1969) and ending with knowledge that incorporates information obtained from site directed mutagenesis and examination of the crystal structures of G proteins (2010). Our current view is that, as it seeks to fill its octahedral coordination shell, Mg acts as a keystone locking the G protein-α subunits into a conformation in which Gα dissociates from the Gβγ dimer, is competent in regulating effectors, and acquires GTPase activity. The latter is the result of moving the backbone carbonyl group of the Mg-coordinating threonine into a location in space that positions the hydrolytic water so as to facilitate the water’s nucleophilic attack that leads to hydrolysis of the link between the β and γ phosphates of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). The role of the backbone carbonyl group of the Mg-coordinating threonine is equi-hierarchical with a similar and long-recognized role of the Switch II glutamine δ amide carbonyl group. Disruption of either leads to loss of GTPase activity.

Keywords: Octahedral coordination shell, regulatory GTPase, GTPase fold, transition state

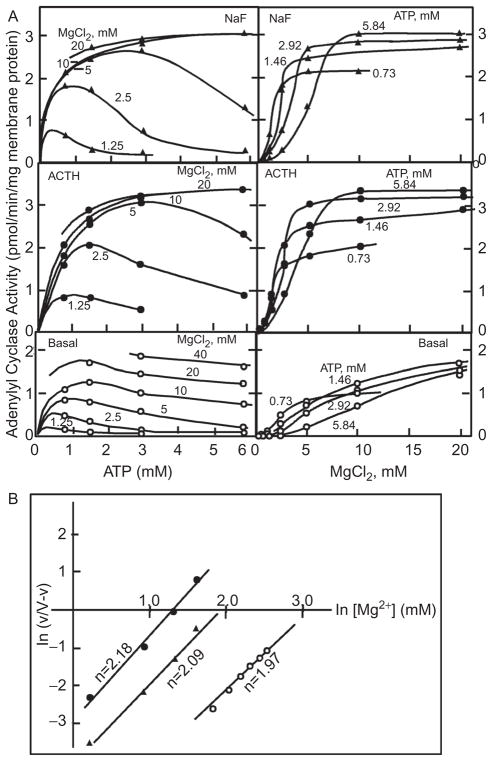

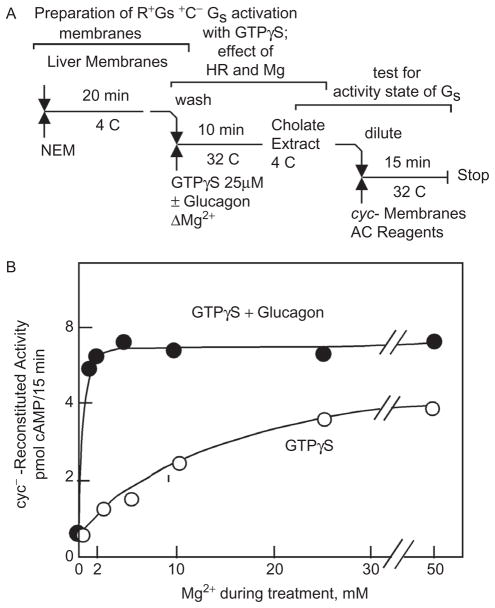

The participation of Mg in the activation of G proteins was recognized before the existence of G proteins was known and before knowing that GTP plays a role in hormone action. That Mg is important emerged from studies in which hormonal activation of adenylyl cyclase in fat cell “ghosts” was explored (1). The results indicated that Mg was likely to be acting allosterically with a positive Hill coefficient of 2 and that hormonal—as well as fluoride—activation shifted the Mg requirement toward lower concentrations (Figure 1). The actual mechanism by which hormonal stimulation affects the requirement for Mg remained mysterious even after: 1. the discovery of a requirement of GTP in hormonal activation of adenylyl cyclase had been made and hormones and fluoride, now AlF4−, were realized to affect adenylyl cyclase through a common mechanism; 2. it had become clear that this mechanism is in fact the activation of the adenylyl cyclase-stimulating heterotrimeric Gs G protein; and 3. it was known that a G-protein activation–deactivation cycle is not only central to the regulation of adenylyl cyclase by receptors but also that of visual phosphodiesterase, phospholipase Cβ, and a host of other effectors, all mediated by a family of 16 heterotrimeric G proteins (reviewed in refs. 2,3). Most notably in promoting to an allosteric site of action of Mg were the results from two-step reconstitution studies in 1982 (5), which showed that high concentrations of Mg substituted for hormonal stimulation in the activation of the Gs protein by the nonhwydrolyzable GTP analogue GTPγS and that the glucagon receptor shifted the requirement for Mg from millimolar (above the affinity constant of GTP for Mg) to micromolar (well bellow that affinity of GTP for Mg) (Figure 2), as this strongly suggested—as Hill plots had done earlier—the existence of a Mg site on Gs, allosteric to the Mg bound by GTP (or its analogue GTPγS).

Figure 1.

The complex interrelationship between the effects of changing the concentrations of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and Mg on adenylyl cyclase activity in the absence and presence of saturating adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or 10 mM NaF (A) reveals that hormonal and fluoride stimulation shift the requirement toward lower concentrations without affecting the apparent cooperative nature of the dependence on Mg (B). Adapted from ref. 1.

Figure 2.

The Mg-dependence of the activation of Gs by GTPγS is shifted from the millimolar concentration range to the micromolar concentration range by the liver membrane glucagon receptor. (A) Three-step assay design: 1. adenylyl cyclase in liver membranes is inactivated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM); 2. Gs in membranes is activated by GTPγS and increasing concentrations of Mg2+, in the absence and in the presence of glucagon; 3. the activation status of Gs is assessed by extraction with cholate and reconstitution of Mg-dependent adenylyl cyclase activity in membranes from Gs-deficient “cyc-“ S49 cells. B. Effect of Mg and glucagon during step 2. Adapted from ref. 5.

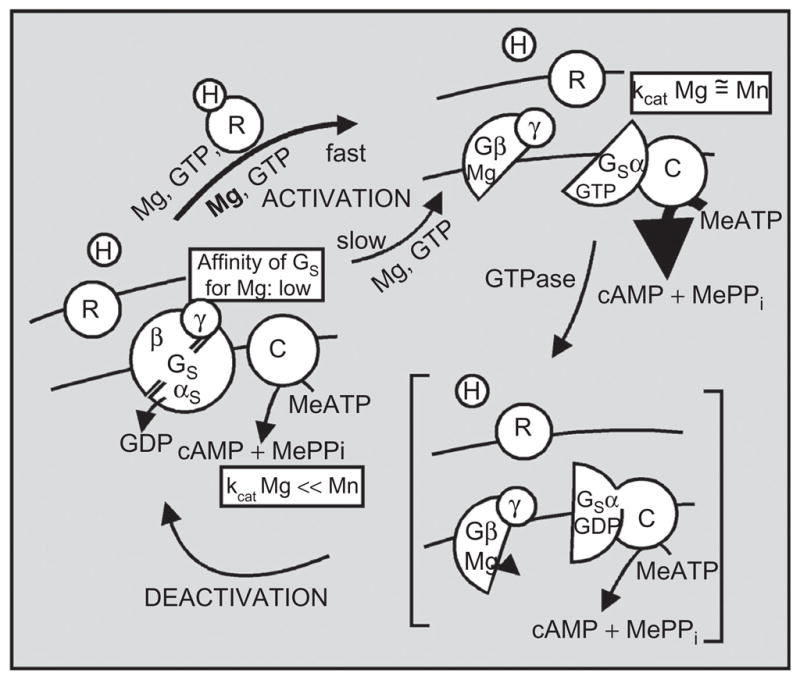

Yet, no allosteric Mg site could be discerned in G-protein crystals—be they made up of the GTPbinding α-subunits alone or of the heterotrimeric Gαβγ complexes. Thus, although one mechanism addressing the possible site of action of Mg affected by the hormone receptor placed the site on the Gβγ (refs. 4,5 and Figure 3), crystals containing Gβγ were devoid of divalent cations. Even so, a review written by one of us in 2006 (2,3), still proposed that the allosteric site might be on the Gβγ dimer.

Figure 3.

1982–1983 model of the signal transduction mechanism mediated by the Gs G protein by which hormone binding to receptor promotes the activation of the G protein that undergoes a subunit dissociation–reassociation cycle driven by the GTPase resident on the α-subunit of Gs. Dissociated Gs-α with Mg–GTP bound to it activates the catalytic unit C of adenylyl cyclase. GTP hydrolysis and reassociation with Gβγ dimer deactivates the transduction system. Receptor is proposed to facilitate the activation of Gs by GTP by promoting the binding of Mg to a hypothetical site on the dissociating Gβγ dimer. Adapted from ref. 4.

Remarkably, the solution to this puzzle was published in a 1997 publication on the biochemical properties of Gi1α mutants from the Sprang-Gilman group that received insufficient attention (6). In this publication, the affinity of the Gi1α–GTPγS complex for Mg was reported to be 8 nM, 5,000 times higher than the 40 μM affinity at neutral pH of GTP or its analogues GTPγS and GMP-P(NH)P for Mg.

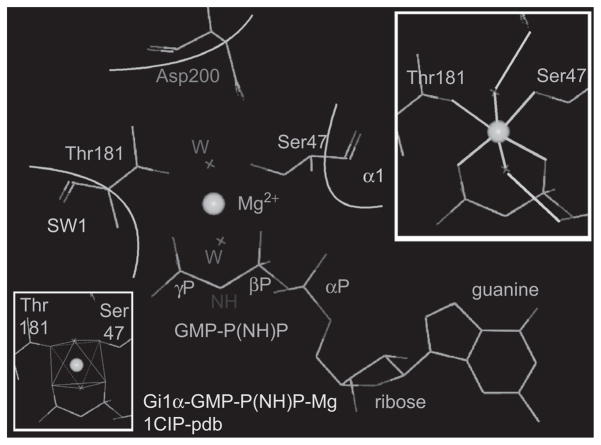

The explanation of this increase in the affinity of GTPγS for Mg when bound to Gi1α became readily evident to us when we compared the mode by which Mg is held by the Gα–GTP complexes in crystals to how Mg is held by free GTPγS. In the latter, the octahedral coordination shell of Mg is filled by the electrons of two GTP oxygens: one each from the β and γ phosphates, and by the electrons from four free water molecules. In contrast, in the GTP–Gα complex, Mg is held not only by the two oxygens from the β and γ phosphates of GTP but also by the coordination bonds of two Gα hydroxyl oxygens: one from a threonine in Switch I and one from a serine at the base of the α1 helix of the GTPase domain. Electrons from two water oxygens complete the coordination shell of Mg in the GTP–Gα complex. These water molecules are in turn held in place by hydrogen bonds to the δ carboxyl group of a Switch II aspartic acid and to the α-phosphate oxygens of the GTP. This results in the formation of a “tight” cage (Figure 4), from which Mg dissociates only very slowly, that is, 5,000 times slower than from GTP or its nonhydrolyzable analogues.

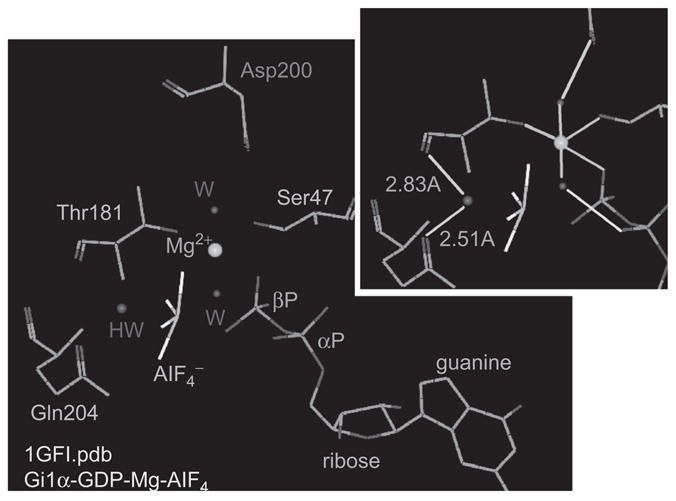

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Mg-binding pocket in GTP-Gi1α. Upper inset: green lines: coordination bonds of Mg; light blue lines: hydrogen bonds. Note that electrons of six oxygens coordinate Mg: one from the β phosphate of GTP, one from the γ phosphate of GTP, one from the hydroxyl of Ser47, one from the hydroxyl of Thr181, and two from a for Mg water molecules stabilized by hydrogen bonds to Asp200 and to the α phosphate of GTP. Lower Inset: octahedral coordination cage.

The Mg, which for many years we had thought to be binding to an allosteric site different from GTP when the activation of the G protein by GTP is facilitated by a receptor, is in fact one and the same. In turn, and as a consequence, Mg can be viewed as a “keystone” that locks GTP into the Gα protein. At this point, the stage is set for a permanent residence of GTP on Gα that can only be undone with expenditure of energy: the hydrolysis of GTP to guanosine diphosphate (GDP) and the loss of one of the coordination bonds holding Mg in place. Opening of the binding pocket by a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) in a cytosolic environment in which the GTP concentration is approximately 10 times higher than that of GDP and in which Mg, at approximately 0.5 mM, is sufficient to saturate GTP, will result in automatic exchange of Mg–GTP for GDP, followed by the clamping of the Mg–GTP complex into place by the Mg-coordinating Ser and Thr residues. This clamping motion carries as its sequel the conformational transitions that Switch I and Switch II need to undergo to confer effector-regulating ability to the G-α subunit.

The Mg-coordinating Thr is part of the Switch I region of the GTPase domain of Gα subunits, and the Mg-coordinating Ser is at the beginning of the α1 helix of the GTPase fold. The Switch I Thr is conserved in not only the Gα subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins but also in “small” regulatory GTPases such as ras, rac, and rho (Table 1). In some of the small GTPases, the α1 helix Ser is replaced by a Thr (Table 1). The Mg-binding cage is the same in small and large GTPases, and the role and effect of Mg binding to the GTP–GTPase complex is the same in small and large GTPases. The Switch II Asp that hydrogen bonds to one of the two water molecules coordinating Mg in GTP–GTPase complexes is also conserved in all regulatory GTPases examined.

Table 1.

Location in the GTPase fold and amino residue number of amino acids involved in coordination of Mg bound to GTP–GTPase complexes and in regulating GTPase activity

| Location | Ser | Thr | Asp | Gln |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| α1 | SWI | SWII | SWII | |

| Gi1α | 47 | 181 | 200 | 204 |

| Gsα(394) | 54 | 204 | 223 | 227 |

| Gtα | 43 | 177 | 196 | 200 |

| H-ras | 17 | 35 | 57 | 61 |

| RAC1 | 17* | 35 | 57 | 61 |

| RhoA | 19* | 37 | 59 | 63 |

| Rab3a | 36* | 54 | 77 | 81 |

Thr instead of Ser.

Replacing Ser16 with an Asn in ras (S16N mutants) and in ras-like regulatory GTPases creates proteins that cannot be locked into an activate conformation by Mg–GTP and are locked in their inactive state with dominant negative properties. Curiously, working with recombinant Gsα, we recently found that mutating Switch I Thr to Asp, Glu, or Gln results not only in diminished GTPase activity but also in spontaneous activation of the Switch II domain (7). This result was unexpected as there was no a priori reason why removal of the Thr should affect the overall GTPase cycle differently than removal of the Ser. As had been earlier, the answer to this seemingly anomalous behavior was found upon close examination of existing α subunit crystals in which we saw the oxygens of the backbone carbonyl of Switch Thr and of the δ-carbonyl of Switch II Gln to be roughly equidistant to the oxygen of the hydrolytic H2O (Figure 5). Failure to shift the position of the Switch I carbonyl, as a consequence of having removed the Thr that participates in the coordination of the Mg, causes loss of the ability of the Gα subunits to hydrolyze GTP and revealed the participation of this threonine in the hydrolytic process. Figure 5 illustrates the positions of the Switch I Thr C1 amide carbonyl oxygen and the Switch II Glu δ carbonyl oxygen in relation to the hydrolytic water oxygen in a crystal of transducin α complexed to Mg-GDP-AlF4−, the transition state in the catalysis of GTP + H20 to GDP + Pi. Loss of either the Thr or the Gln results in loss of GTPase activity and stabilization of the active effector-regulating conformation.

Figure 5.

Hydrogen bonds to the backbone carbonyl of Thr181 and to the γ amide of Glu204 position the hydrolytic water (HW) to facilitate the nucleophilic attack of the βγ phosphodiester bond of GTP as inferred from the transition state on a GDP-Mg-AlF4-Gi1α complex. AlF4 occupies the place of the γ phosphate of GTP. Inset: green lines, coordination bonds to Mg; light blue lines, hydrogen bonds; light blue numbers: atomic distances in Angstroms.

Conclusion

We wrote this short historical overview on the evolution of our thoughts between 1969 and the present on how and where Mg acts in setting G-protein activity, not only in recognition of the pivotal role this Journal has had in publishing factual science papers but also in publishing papers presenting thoughts on the trends of the moments in which they were published. The latter publications included the proceedings of the Swiss Receptor Workshops attended by one of us (LB) many times between their inception in 1981 until the end of the 1990s. We also wrote this article in honor of Alex Eberle’s long career in Science. We did so hoping that he would identify with the underlying meaning of this account. Just as the scientific question we dealt with evolved and never lost relevance, so did Alex’s career and contributions evolve and never lost relevance.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH (Z01-ES-101643).

References

- 1.Birnbaumer L, Pohl SL, Rodbell M. Adenyl cyclase in fat cells. 1. Properties and the effects of adrenocorticotropin and fluoride. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:3468–3476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnbaumer L. The discovery of signal transduction by G proteins: a personal account and an overview of the initial findings and contributions that led to our present understanding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:756–771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnbaumer L. Expansion of signal transduction by G proteins. The second 15 years or so: from 3 to 16 alpha subunits plus betagamma dimers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:772–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaumer L, Kirchick HJ. Regulation of gonadotropin action: The mechanisms of gonadotropin-induced activation of ovarian adenylyl cyclases. In: Greenwald GS, Terranova PF, editors. Factors regulating ovarian function. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar R, Birnbaumer L. Hormone receptor modulates the regulatory component of adenylyl cyclase by reducing its requirement for Mg2+ and enhancing its extent of activation by guanine nucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5179–5183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raw AS, Coleman DE, Gilman AG, Sprang SR. Structural and biochemical characterization of the GTPgammaS-, GDP. Pi-, and GDP-bound forms of a GTPase-deficient Gly42 –> Val mutant of Gialpha1. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15660–15669. doi: 10.1021/bi971912p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zurita A, Zhang Y, Pedersen L, Darden T, Birnbaumer L. Obligatory role in GTP hydrolysis for the amide carbonyl oxygen of the Mg(2+)-coordinating Thr of regulatory GTPases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9596–9601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004803107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]