The use of bupivacaine irrigated over the surgical bed was found to be an effective method for reducing pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, Irrigation, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Postoperative pain

Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of bupivacaine irrigated at the surgical bed on postoperative pain relief in laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients.

Methods:

This study included 60 patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy who were prospectively randomized into 2 groups. The placebo group (n=30) received 20cc saline without bupivacaine, installed into the gallbladder bed. The bupivacaine group (n=30) received 20cc of 0.5% bupivacaine in at the same surgical site. Pain was assessed at 0, 6, 12, and 24 hours by using a visual analog scale (VAS).

Results:

A significant difference (P=.018) was observed in pain levels between both groups at 6 hours postoperatively. The average analgesic requirement was lower in the bupivacaine group, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions:

In our study, the use of bupivacaine irrigated over the surgical bed was an effective method for reducing pain during the first postoperative hours after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered the gold standard treatment for benign gallbladder disease. It is characterized by a short hospital stay and an early return to regular activity. 1,2,3 Strategies to handle the different intraabdominal surgical pathologies with a laparoscopic approach offer a significant benefit compared with the conventional technique. 1,2

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has improved surgical outcome in terms of reduced pain and convalescence compared to conventional cholecystectomy.1,2 However, the postoperative pain is considerable. Pain management with multiple analgesic and opioids has been reported with variable success. 1,2,4

The pain in the conventional cholecystectomy is a parietal pain. In laparoscopic cholecystectomy, pain is derived from multiple situations: incision pain (somatic), deep intraabdominal pain (visceral), and shoulder pain (visceral pain due to phrenic nerve irritation). 5,6

In 17% to 41% of the patients, pain is the main cause for staying overnight in the hospital the day of surgery 2–7 and the primary reason why the patients have a longer convalescence. 6,8,9

Because postoperative pain after laparoscopic surgery is complex, specialists suggest that effective analgesic treatment should be a multimodal support. 3,4,8–15 This type of support consists on establishing empathy with patients, making them feel confident, explaining the procedure and its complications, and administration of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic agent an hour before surgery. 6,10,12–14 It should also include blocking the sensitive aferences (infiltrating the skin with a local anesthetic before any incision), administration of an opioid perioperatively, irrigating a local anesthetic in the peritoneal cavity, providing the patient with fluids and electrolytes.5,6,8,10,14–20.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of the irrigation of a local anesthetic, such as bupivacaine, at the surgical bed for postoperative pain reduction. Secondly, we tried to assess whether this analgesia method reduces the postoperative use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID).

METHODS

Eligible participants were from 15 to 60 years old, undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We decided to use an experimental, prospective, randomized design. From September 2010 to July 2011, male and female patients were registered. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, open cholecystectomy, and acute cholecystitis. Patients undergoing chronic treatment with any analgesic or anti-inflammatory agents were also excluded.

This study took place at the Metropolitano “Dr. Bernando Sepúlveda” Hospital in Monterrey, Mexico, from September 2010 to July 2011. It was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Tecnologico de Monterrey–Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud and the Research and Ethics Committee at Hospital Metropolitano “Dr. Bernando Sepúlveda” where this protocol was performed. Informed and written consent was obtained from all participants in the trial.

Sixty patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy were prospectively randomized into 2 groups with concealment of the random sequence. In the control or placebo group, 20cc of normal saline solution without bupivacaine was irrigated at the surgical bed after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The experimental group was irrigated with 20cc of bupivacaine 0.5% in normal saline solution.

Before surgery, all the patients underwent upper abdominal ultrasound, EKG, chest X-rays, a complete blood count, liver function test, and a coagulation profile. All patients were referred to the operating room without premedication, and the induction was performed using cisatracurium or vecuronium, propofol, and fentanyl. A customized dose for each patient was used.

A standard operative method was used with a 4-trocar technique in all patients. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved in every case with the use of a Veress needle through a periumbilical incision, and was maintained at 14mm Hg during the entire surgical procedure. After removal of the gallbladder, hemostasis was performed at the surgical bed. After gallbladder extraction, randomization was performed using a computer program (www.randomized.com). Irrigation of the surgical bed was done with the insertion of a feeding tube through the right subcostal port. After irrigation of the gallbladder, gas, instruments, and trocars were removed. No drains were used. There were no complications in the perioperative period in any patient.

Pain was assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) of 0 to 10. Assessment was carried out in the recovery room at 30 minutes and 60 minutes postoperatively. Measurement in the patients room was performed 6,12, and 24 hours after surgery. All the patients were allowed to receive analgesic medication as needed, and the requirement of these medications was recorded. VAS was explained to every patient. The number “0” was equivalent to no pain, and “10” was the worst pain they ever felt. Administration of analgesics was correlated with the reading of VAS. Timing of the initial administration of analgesics was also recorded. Different IV analgesics, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), were used to reduce the postoperative pain.

Evaluation of postoperative symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and fever, were also recorded at the hospital stay. Initiation of oral intake and ambulation were also recorded.

Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed t test and chi-square analysis; significance was determined as P<.05.

Kaplan-Meier curves and Log Rank test were used to assess differences over time. The descriptive variables were analyzed either by chi-square analysis or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. P<.05 was considered statically significant.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Sixty patients were included in this protocol; 55 were women and 5 were men ranging in age from 15 to 54 years. The average in the bupivacaine group was 29 years and in the control group 36 years. The result was significant for the age in both groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Data

| Characteristics | Bupivacaine Group | Placebo Group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female/Male | 30/30 | 25/30 | .520 |

| Age (SD)a | 29.7 (9.2) | 36.7 (9.5) | .01b |

Statistically significant.

SD=standard deviation.

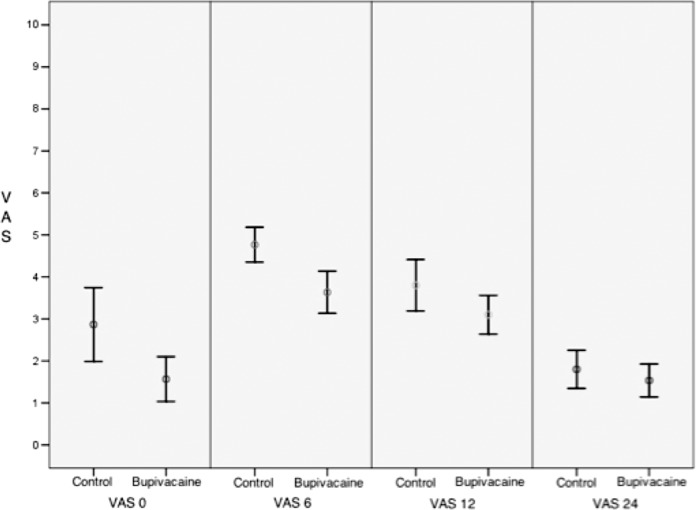

A significant difference occurred in the average pain levels at 6 hours postoperatively between the control and experimental groups (Table 2). No significant difference occurred between the 2 groups during the other time intervals (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Comparison Between Groups

| Visual Analog Scaleb | Processing Group (Bupivacaine) n=30 | Control Group (Placebo) n=30 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain T0 | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–5) | .070 |

| p50 (p25–p75) | |||

| Pain T6 | 3.50 (2.75–5) | 5 (4–5.25) | .02a |

| p50 (p25–p75) | |||

| Pain T12 | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | .605 |

| p50 (p25–p75) | |||

| Pain T24 | 1.50 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | .704 |

| p50 (p25-p75) |

Statistically significant.

p50, median; p25-p50, interquartile rank.

Figure 1.

Comparison between pain groups.

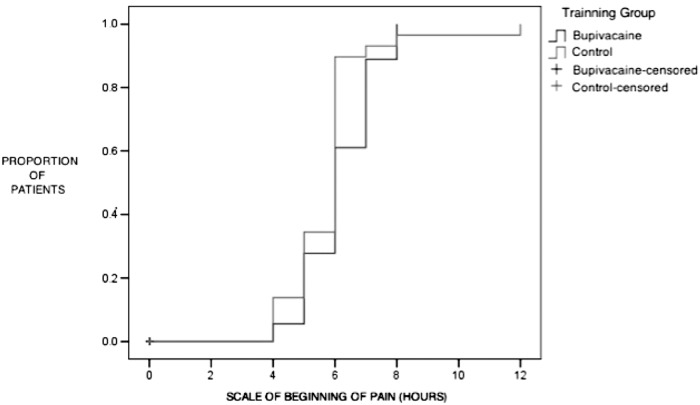

The patients that needed analgesics asked for their first dose at 4 hours postoperative time. The average analgesic requirement was lower in the bupivacaine group, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scale of beginning of pain.

Nausea was the most common postoperative symptom reported, with an incidence of 30% in the experimental group and 40% in the control group. There was no significant statistical difference. Two patients experienced vomiting, one from each group with no significant difference. Only 1 patient in the control group experienced fever. This patient was treated with 500mg of acetaminophen by mouth every 6 hours during his hospital stay and was discharged the second postoperative day (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Postsurgical Symptoms

| Postsurgical Symptoms | Processing Group (Bupivacaine) n=30 | Control Group (Placebo) n=30 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea n (%) | 9 (30) | 13 (43.3) | .422 |

| Vomiting n (%) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1 |

| Fever n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 |

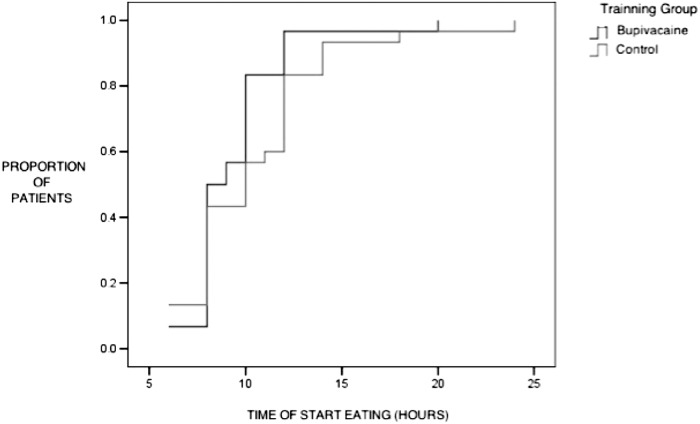

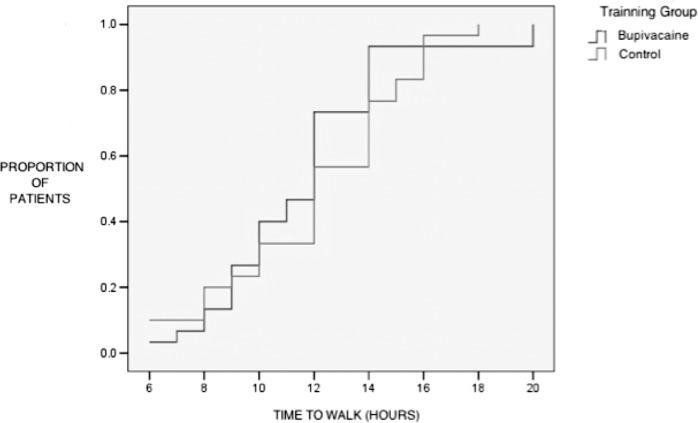

Oral intake and ambulation are shown in Table 4. No statistical differences were found (Figures 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Recovery Indices

| Variablesa | Processing Group (Bupivacaine) n=30 | Control Group (Placebo) n=30 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to start eating hr p50 (p25-p75) | 8.5 (8–10) | 10 (8–12) | .44 |

| Time to walk hr p50 (p25-p75) | 12 (9–14) | 12 (9.75–14.25) | .28 |

p50, median; p25-p75, interquartile rank.

Figure 3.

Scale of start eating.

Figure 4.

Scale of time to walk.

Of the 60 patients included in the study, 47 required intravenous postoperative analgesics; 18 patients were from the bupivacaine group and 29 from the control group. A statistically significant difference (P=.018) (Table 5) was observed. This difference was mainly noted at the 6-hour interval postoperatively.

Table 5.

| Processing Group (Bupivacaine) n=30 | Control Group (Placebo) n=30 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesia Required n (%) | 18 (60) | 29 (96.7) | .018a |

Statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most frequently performed elective surgeries. It is a short stay procedure, and therefore, adequate postoperative pain relief is of considerable importance, which makes it ideal for patients.

Postoperative pain in these patients is observed in peaks immediately after surgery and decreases after 24 postoperative hours. The cause of early postoperative pain in laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not clearly understood. This study demonstrates that 0.05% bupivacaine irrigation at the surgical bed decreases pain in laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients. With our results, we assumed that early postsurgical pain was generated by irritation of the peritoneum, and the application of bupivacaine may relieve this pain.

Of the 30 patients in the bupivacaine group, 12 did not require immediate analgesia based on their VAS recording of tolerable pain. In the placebo group, only 1 patient did not require analgesia. Even so, the pain experienced by both groups was of moderate intensity. The most common location for this pain was the right upper quadrant followed by pain at the trocar sites.

VAS in both groups was significantly different for the decrease in pain in patients irrigated with bupivacaine at 6 postoperative hours. We conclude that there was better control of visceral pain during the first postoperative hours, which may be associated with the time of bupivacaine duration, which is from 3 hours to 10 hours on average.

Importantly, pain is a manifestation that varies from one person to another, depending largely on the pain threshold of each person and how each perceives pain, so today the tools to measure pain are subjective. VAS is based on the results of each patient's verbal comments. This study indicates that it is feasible to perform this type of procedure to have better control of postoperative pain in ambulatory laparoscopic surgery.

The most common postoperative symptom in this study was nausea in 22 patients, and this was not significantly different between groups. It was followed by vomiting in 2 patients and fever in 1 patient. Therefore, we can conclude that the use of bupivacaine can reduce the postoperative pain occurring in the first hours after the surgery. But this does not cause a decrease in other symptoms such as nausea.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that irrigation with bupivacaine at the surgical bed in laparoscopic cholecystectomy will significantly lower the intensity of postoperative visceral pain, as well as analgesic consumption in the first postsurgical hours. Because of this, we can establish this protocol for use in laparoscopic cholecystectomies with the purpose of a faster return of the patient to his or her normal life, and thus, a shorter hospital stay. Finally, bupivacaine at the dosage used were very safe and had no significant side effects. Therefore, we can reduce pain in patients who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy in ambulatory centers. This practice can become permanent in these cases.

Contributor Information

Gerardo Castillo-Garza, General Surgery, Tecnologico de Monterrey-Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud. Postgraduate Area, Monterrey, N. L. México..

José A. Díaz-Elizondo, General Surgery, Tecnologico de Monterrey-Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud. Postgraduate Area, Monterrey, N. L. México..

Carlos A. Cuello-García, Evidence Based Medicine Center, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud, Monterrey, N. L. México..

Oscar Villegas-Cabello, General Surgery, Tecnologico de Monterrey-Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud. Postgraduate Area, Monterrey, N. L. México..

References:

- 1. Downs SH, Black NA, Devlin HB, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1996;78:241–323 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lau H, Brooks DC. Predictive factors for unanticipated admissions after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1150–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fiorillo MA, Davidson PG, Fiorillo M, et al. 149 ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Callesen T, Klarskov B, Mogensen, et al. Day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy: feasibility and convalescence. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160:2095–2100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Rosenberg J, et al. Characteristics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain. 2001;90:261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. David CW. Analgesic treatment after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:835–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tuckey JP, Morris GN, Peden CJ, et al. Feasibility of day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy in unselected patients. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:965–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Pain and convalescence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;167:84–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Rosenberg J, et al. Factors determining convalescence after uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2001;136:917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wills VL, Hunt DR. Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Narchi P. Intraperitoneal local anaesthetic for shoulder pain after day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lancet. 1991;338:1569–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pascalucci A. Preemptive analgesia: Intraperitoneal local anesthetic cholecystectomy. A randomized double blind, placebo controlled study. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gordon S. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine and saline were similar in preventing pain after extensive laparoscopic excision of endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnes PJ, Belvisi MG, Rogers DF. Modulation of neurogenic inflammation: Novel approaches to inflammatory disease. Trend Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11:185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joris J, Thiry E, Paris P, et al. Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: characteristics and effect of intraperitoneal bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards ND, Barclay K, Catling SJ, et al. Day case laparoscopy: a survey of postoperative pain and an assessment of the value of diclofenac. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:1077–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupta A, Thorn S, Axelsson K, et al. Postoperative pain relief using intermittent injections 0.5% ropivacaine through a catheter after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:450–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahmed B, Ahmed A, Tan D, et al. Post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy pain: effects of intraperitoneal local anesthetics on pain control–a randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am Surg. 2008;74:201–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lepner U, Goroshina J, Samarutel J. Postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomised prospective double-blind clinical trial. Scand J Surg. 2003;92:121–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim T, Kang H, Park J, et al. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine instillation for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Korean Surg Soc. 2010;79:130–136 [Google Scholar]