Delayed minimally invasive hysterectomy should be considered in women with placenta percreta in order to lessen morbidity and speed postoperative recovery.

Keywords: Placenta percreta, laparoscopic hysterectomy

Abstract

Placenta percreta is a problem encountered with increasing frequency due to the rising rate of cesarean delivery. Conservative management of this condition is associated with decreased perioperative morbidity. When hysterectomy is necessary, a laparoscopic approach can provide additional benefits. We present the case of a woman with placenta percreta with bladder invasion who was undergoing conservative management and then required delayed hysterectomy. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy was successfully performed. We review the techniques used to ensure a good outcome and the advantages of a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy in this patient with placenta percreta.

INTRODUCTION

The rate of abnormal placentation has risen from 1:2500 to 1:530 deliveries over the past 20 years in conjunction with the increasing frequency of cesarean delivery.1,2 Placenta accreta, a condition in which the placenta is abnormally adherent to the myometrium due to the absence of the decidua basalis and defective development of Nitabuch's layer, accounts for approximately 75% of cases of abnormal placentation. Around 20% are placenta increta and about 5% are placenta percreta, in which the placenta invades into the myometrium and through the uterine serosa, respectively.2 Placenta percreta carries a high risk of maternal morbidity, including massive hemorrhage, need for transfusion, infection, urinary tract injury, fistula formation, and death, with maternal mortality rates as high as 5% to 7%.3–8

Two main options are available for management of placenta accreta at the time of delivery: cesarean-hysterectomy and conservative management. A third option, extirpative management, is not recommended due to the likelihood of massive hemorrhage when the placenta is forcefully removed from the uterus.7,8 In the conservative approach, the placenta is left in situ at the time of cesarean delivery. The placenta can then be spontaneously absorbed or expelled, or hysterectomy can be performed at a later date if indicated. In cases of placenta percreta, conservative management has been found to decrease blood loss, need for transfusion, and episodes of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).7–9 The decreased morbidity and the possibility of fertility preservation support the use of conservative management in select patients.6–8 However, the risks of delayed hemorrhage, infection, and other late complications like fistula formation still exist.3,5–7,10–12

The majority of the case reports and studies published on conservative management of placenta accreta describe a second laparotomy if hysterectomy is later performed.3–11,13–15 Laparotomy is generally associated with higher complication rates, longer hospital stays, and longer recovery times compared to laparoscopy. Ochalski et al16 reported additional benefits of laparoscopic management of placenta percreta, including increased visualization allowing superior dissection as well as improved hemostasis attributed to pneumoperitoneum. In addition, the faster postoperative recovery associated with laparoscopy likely results in less disruption of the lives of mothers and their newborns. In the following case report, we present a patient who underwent delayed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta, and illustrate the techniques used to ensure a good outcome.

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old, G3P1102, female with a history of 2 prior cesarean deliveries was found to have placenta previa on ultrasound at 13 weeks gestation. She experienced her first episode of vaginal bleeding shortly thereafter. On follow-up ultrasound performed at 23 weeks, placenta accreta was suspected on the basis of multiple vascular placental lakes visualized near the left anterolateral lower uterine segment. The patient was later admitted when she presented with painless vaginal bleeding at 27 weeks gestation. Serial ultrasonography with Doppler studies as well as abdominal and pelvic MRI revealed evidence of placenta percreta at the dome of the bladder. The patient remained hospitalized throughout the remainder of her pregnancy and experienced 2 additional small episodes of vaginal bleeding, with fetal and maternal well being remaining reassuring. The risks and benefits of conservative management were discussed with the patient, and she desired to proceed with the plan to leave the placenta in situ at the time of cesarean delivery.

At 36 weeks and 4 days gestation, the patient underwent scheduled cesarean delivery. A multidisciplinary support team and appropriate blood products were available. A fundal vertical uterine incision was made to avoid the placenta, and the infant was delivered. The umbilical cord was ligated and transected near its placental insertion, and the placenta was left in situ. The anterior lower uterine segment was significantly hypervascular and had a violaceous discoloration at its interface with the bladder, supporting the diagnosis of placenta percreta. This portion of the uterus also appeared to bulge into the bladder. The urology service was present and could not rule out placental invasion of the bladder. Therefore, the decision was made to proceed with the plan for conservative management to avoid the significant risk of hemorrhage and need for partial cystectomy. The uterine incision was closed, and the patient was taken to the Interventional Radiology suite for uterine artery embolization. All procedures were completed without complication, and estimated blood loss was 500mL.

The patient's postoperative course was uncomplicated. She was discharged home on postoperative day 4, and returned to the clinic for serial ultrasound examinations as an outpatient. These examinations demonstrated a uterus measuring 18cm x 9cm x 11cm, with markedly reduced blood flow to the uterus and cervix as well as cervical funneling.

On postoperative day 16, the patient reported fever to 39.4°C and increased abdominal pain. On examination, the cervix was indistinct from the lower uterine segment. The uterus was 16 weeks size and was moderately tender to palpation throughout. Given the concern for endomyometritis secondary to the retained placenta, the decision was made to proceed with a minimally invasive hysterectomy at that time.

A laparoscopic-assisted vaginal approach was used. A left upper quadrant entry was performed to avoid inadvertent injury to the uterine fundus and to provide an adequate view of the enlarged uterus and pelvic anatomy. We proceeded with laparoscopic hysterectomy in the usual fashion, first dessicating and transecting the utero-ovarian ligaments, fallopian tubes, and round ligaments, and then isolating the uterine vasculature using the Harmonic ACE (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH). Because the uterine vessels were >5mm in diameter, the Kleppinger bipolar forceps were used to dessicate them before their transection.

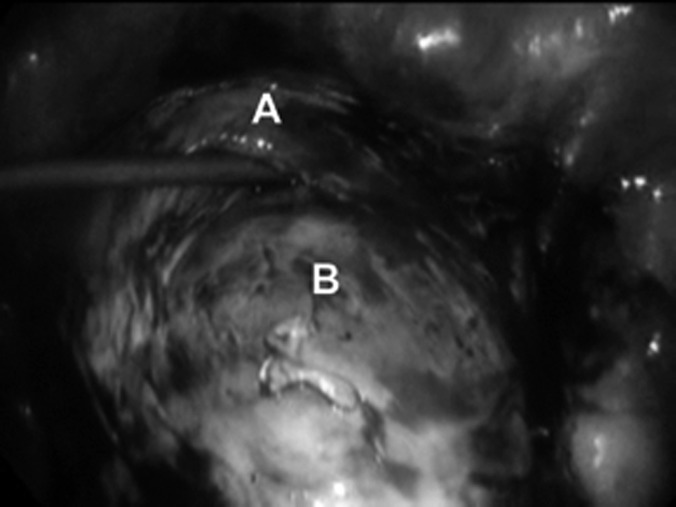

The bladder adjacent to the uterus was noted to be thickened and vascular, consistent with the prior diagnosis of placenta percreta. Aided by the magnification provided by the laparoscope, sharp and blunt dissection were used to carefully create the bladder flap. In addition, the lower uterine segment was significantly distended due to the retained placenta, making identification of the cervico-vaginal junction difficult (Figure 1). To debulk the lower uterine segment, we proceeded vaginally, and with ring forceps we were able to evacuate much of the placental tissue transcervically in a piecemeal fashion. Because the blood supply to the uterus had been secured laparoscopically, no significant bleeding was encountered while removing this tissue. The placenta was notably necrotic and malodorous, supporting the diagnosis of endomyometritis due to the retained placenta. After removal of this tissue, the anterior and posterior colpotomies were safely created utilizing both laparoscopic and vaginal approaches. The uterus was removed intact through the vagina, and the cuff was closed vaginally.

Figure 1.

The bladder (A) was dissected from the invasive placenta at the lower uterine segment (B). Note the significant distention of the lower uterine segment by the placenta.

Cystoscopy was performed at the close of the surgery, and hypervascularity was noted approximately 2cm cephalad to the trigone, also consistent with the diagnosis of placenta percreta. In addition, normal efflux of indigo carmine was seen from the bilateral ureteral orifices. Estimated blood loss was 300mL. Pathology report later revealed degeneration, necrosis, and inflammation of myometrial tissue, which precluded diagnosis of placenta percreta.

The patient's postoperative course was unremarkable. She completed a course of ampicillin and gentamicin and rapidly defervesced. At her 6-week postoperative visit, the patient was doing extremely well. On examination, a small amount of granulation tissue was noted at the vaginal cuff, which was treated with silver nitrate. The patient had no other remarkable findings or complaints.

DISCUSSION

In this case report, we present several factors that contributed to our ability to successfully complete a minimally invasive hysterectomy in this patient with placenta previa percreta. First, the uterine blood supply remained generous, even several weeks after delivery and uterine artery embolization. Securing the uterine vasculature early in the procedure diminished the risk of hemorrhage. Second, magnification by the laparoscope aided the dissection of the vascular and inflamed tissue present at the interface of the bladder and lower uterine segment, decreasing chances of cystotomy. Cystoscopy at the completion of the procedure was an important step to confirm that no urinary tract injury had occurred. Third, due to the placenta previa, the lower uterine segment was enlarged, nearly to the diameter of the fundus, making the junction between the vagina and cervix indistinct. Evacuation of placental tissue (after the uterine vascular supply had been secured) resulted in decompression of the lower uterine segment and allowed improved visualization of and access to the sites at which the colpotomy incisions were to be made. Using a combined vaginal and laparoscopic approach during creation of the colpotomy lessened the risk of cystotomy while operating on adhesed and inflamed tissue. Finally, the combined efforts of a multidisciplinary team, which included specialists from Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Urology, Anesthesiology, and Radiology, were of utmost importance in preparing for this surgery and providing the highest quality of care for this patient.

Our report does have limitations. The use of adjuvant treatments like uterine artery embolization in women with placenta percreta remains controversial.3,17 Uterine artery ligation is an alternative to uterine artery embolization and has been used for both prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage.18–21 However, several authors have identified placenta previa and placenta accreta as risk factors for failure of uterine artery ligation.18,20,21 O'Leary20 believed these failures were “perhaps explained by the richer collateral circulation that develops in the presence of abnormal placentation.” A systematic review performed in 2007 found no evidence to support the superiority of any one conservative surgical or radiologic treatment modality for the management of postpartum hemorrhage.22 Similarly, the optimal plan for follow-up and timing of delayed hysterectomy in women being managed conservatively is unknown.3,23 Because no conclusions can be reached regarding the optimal treatment plan for patients with placenta previa percreta, we chose uterine artery embolization followed by delayed hysterectomy to deplete the rich vascular supply of the invasive placenta.

Another important clinical point is to differentiate postembolization syndrome from endomyometritis after uterine artery embolization. Pelvic pain requiring narcotics is expected after embolization and may be associated with nausea, malaise, and low-grade fevers for 2 days to 7 days. This is known as postembolization syndrome. It can be distinguished from endomyometritis, which is associated with high fever, increasing pain, and possibly purulent vaginal discharge between 1 week and 6 months after embolization.24 A reliable patient who is able to understand the risks and benefits and follow-up regularly is required to proceed with conservative management. Although this treatment plan is associated with a decreased rate of severe morbidity, the risks of hemorrhage, infection, and disseminated intravascular coagulation still exist.3,5,6,8–11 The re-presentation of our patient with evidence of infection highlights this possibility. In addition, patients undergoing delayed hysterectomy are exposed to the usual risks of surgery and anesthesia for a second time in a matter of weeks to months, regardless of the surgical approach, which must also be taken into consideration. Despite these limitations, we believe delayed minimally invasive hysterectomy was the best option for our patient.

CONCLUSION

Placenta previa percreta is a condition associated with a high surgical complication rate when managed with cesarean-hysterectomy. Conservative management is one treatment option that may be associated with decreased morbidity. Our patient required delayed hysterectomy due to infection and benefitted from the use of a minimally invasive approach. Decreased length of hospital stay and decreased recovery time were key factors allowing her to continue to care for and bond with her newborn infant. The techniques we used, including early ligation of the uterine vasculature, careful dissection of the bladder away from the uterus, removal of placental tissue to decompress the lower uterine segment, and use of vaginal and laparoscopic views to facilitate colpotomy creation allowed us to avoid hemorrhage and bladder injury. Involvement of a multidisciplinary team in surgical preparation also contributed to our patient's positive outcome. Risks of delayed minimally invasive hysterectomy exist; however, this approach should be considered a viable option in women with placenta percreta to lessen morbidity and speed postoperative recovery.

Contributor Information

Bethany D. Skinner, Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA..

Alan M. Golichowski, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA..

Gregory J. Raff, Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA..

References:

- 1. Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1458–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(1):210–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Timmermans S, van Hof AC, Duvekot JJ. Conservative management of abnormally invasive placentation. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(8):529–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee PS, Bakelaar R, Fitpatrick CB, Ellestad SC, Havrilesky LJ, Alvarez Secord A. Medical and surgical treatment of placenta percreta to optimize bladder preservation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 2):421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Angstmann T, Gard G, Harrington T, Ward E, Thomson A, Giles W. Surgical management of placenta accreta: a cohort series and suggested approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(1):38.e1–9 Epub 2009 Nov 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silver LE, Hobel CJ, Lagasse L, Luttrull JW, Platt LD. Placenta previa percreta with bladder involvement: new considerations and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9(2):131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kayem G, Davy C, Goffinet F, Thomas C, Clement D, Cabrol D. Conservative versus extirpative management in cases of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):531–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sentilhes L, Ambroselli C, Kayem G, et al. Maternal outcome after conservative treatment of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3):526–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diop AN, Chabrot P, Bertrand A, et al. Placenta accreta: management with uterine artery embolization in 17 cases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(5):644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hays AM, Worley KC, Roberts SR. Conservative management of placenta percreta: experiences in two cases. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 2):425–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Teo SB, Kanagalingam D, Tan HK, Tan LK. Massive postpartum haemorrhage after uterus-conserving surgery in placenta percreta: the danger of the partial placenta percreta. BJOG. 2008;115(6):789–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Diop AN, Bros S, Chabrot P, Gallot D, Boyer L. Placenta percreta: urologic complication after successful conservative management by uterine arterial embolization: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):e7–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parva M, Chamchad D, Keegan J, Gerson A, Horrow J. Placenta percreta with invasion of the bladder wall: management with a multi-disciplinary approach. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(3):209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sumigama S, Itakura A, Ota T, et al. Placenta previa increta/percreta in Japan: a retrospective study of ultrasound findings, management and clinical course. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33(5):606–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu PC, Ou HY, Tsang LL, Kung FT, Hsu TY, Cheng YF. Prophylactic intraoperative uterine artery embolization to control hemorrhage in abnormal placentation during late gestation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(5):1951–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ochalski ME, Broach A, Lee T. Laparoscopic management of placenta percreta. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(1):128–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alanis M, Hurst BS, Marshburn PB, Matthews ML. Conservative management of placenta increta with selective arterial embolization preserves future fertility and results in a favorable outcome in subsequent pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1514.e3–7 Epub 2006 Sep 27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fahmy K. Uterine artery ligation to control postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1987;25(5):363–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrazzani S, Guariglia L, Triunfo S, Caforio L, Caruso A. Conservative management of placenta previa-accreta by prophylactic uterine arteries ligation and uterine tamponade. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;25(4):400–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Leary JA. Uterine artery ligation in the control of postcesarean hemorrhage. J Reprod Med. March 1995;40(3):189–193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verspyck E, Resch B, Sergent F, Marpeau L. Surgical uterine devascularization for placenta accreta: immediate and long-term follow-up. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84(5):444–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doumouchtsis SK, Papageorghiou AT, Arulkumaran S. Systematic review of conservative management of postpartum hemorrhage: what to do when medical treatment fails. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(8):540–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. El-Bialy G, Kassab A, Armstrong M. Magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) and serial beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-hCG) follow up for placenta percreta. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276(4):371–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leonhardt H, Aziz A, Lonn L. Post-embolization syndrome and complete expulsion of a leiomyoma after uterine artery embolization. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. March 84(3):303–305, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]