The authors conclude that laparoscopic repair of traumatic intraperitoneal urinary bladder rupture is a practical alternative to conventional open repair.

Keywords: Bladder repair, Blunt trauma, Laparoscopy, Intracorporeal

Abstract

Laparoscopic repair of the traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture is a proven, safe, and effective technique in the appropriate setting. A 23-year-old male with traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture proven by cystogram after a motor vehicle collision was successfully repaired via a laparoscopic approach. We describe the technique in detail including 2-layer closure and follow-up care. A review of the literature using PubMed with the key words [laparoscopic repair bladder injury] AND [bladder trauma] was performed. We recommend the consideration of laparoscopic repair of the intraperitoneal bladder rupture in more trauma patients who meet criteria.

INTRODUCTION

Less than 2% of all blunt abdominal trauma results in traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture. Conventional means of repair have included laparotomy, with its own associated morbidity. While laparoscopic bladder repair is not a novel technique, its use in the trauma setting has been infrequent. Herein, we describe our use of laparoscopy for the repair of an intraperitoneal bladder rupture following blunt abdominal trauma.

CASE REPORT

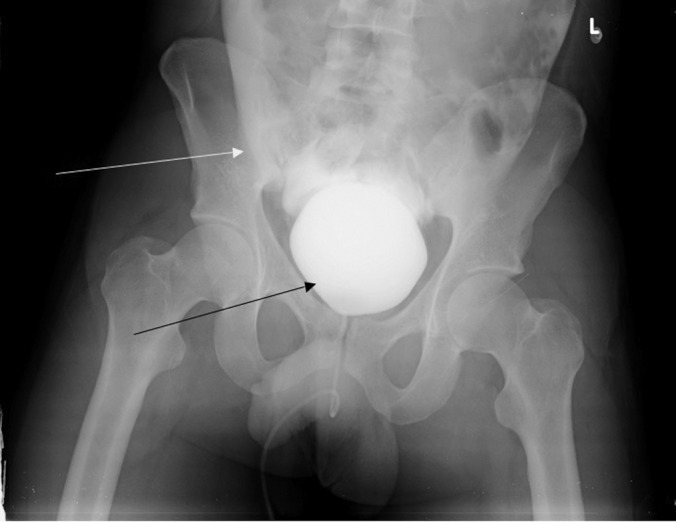

We report the case of a 23-year-old male involved in a motor vehicle collision as a restrained passenger. He had been drinking alcohol prior to the collision. Upon presentation to the trauma service, he was complaining of right hip pain; otherwise he was hemodynamically stable. He did not have any markings on his abdomen nor pelvis region such as a “seatbelt sign.” After an initial evaluation, he was taken to radiology where a CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis was performed. There was a moderate amount of fluid in his pelvis, which on closer inspection appeared to be a disruption in his bladder wall. A retrograde cystogram confirmed our suspicion of an intraperitoneal bladder injury, and the patient was taken to the operating room (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Retrograde cystogram. Bladder filled with contrast (bottom arrow). Extravasation of contrast (top arrow).

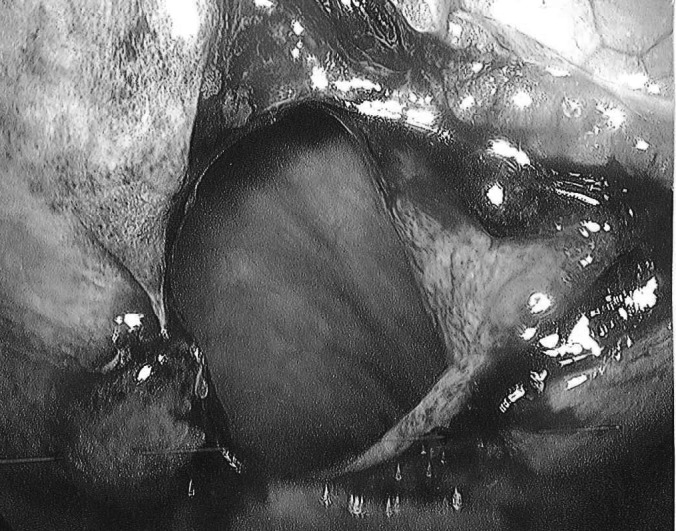

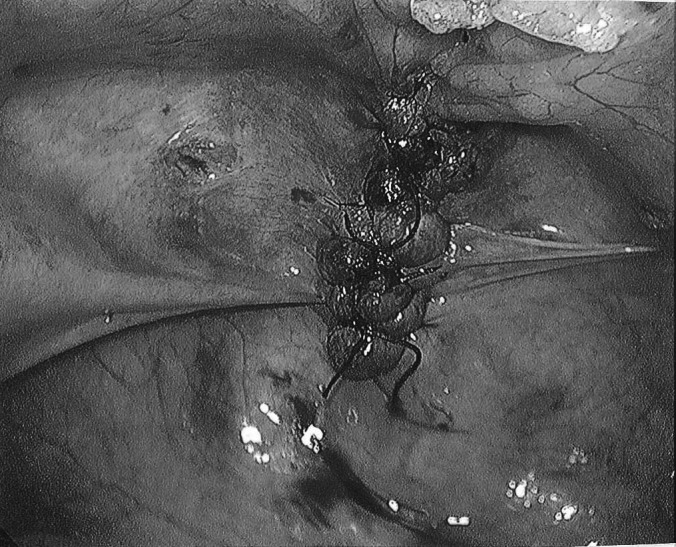

Because this patient remained hemodynamically stable and the only other injury was a pubic rami fracture, we decided to perform a laparoscopic repair of this injury. First, a cystoscopy was performed to ensure the injury was at the dome of the bladder, and not involving the ureters or the trigone. Second, bilateral 5-French ureteral catheters were inserted as well as a 24-French Foley catheter. Next, we performed laparoscopic repair of the intraperitoneal bladder injury. We used a 12-mm infraumbilical port and two 5-mm ports laterally. Upon entering the abdomen, the entire abdominal contents were examined and noted to be without other injuries. There was a mild amount of bloody urine in the pelvis at the posterior cul-de-sac. A 3-cm defect was noted at the dome of the bladder (Figure 2). The Foley catheter was visualized within the bladder defect. We repaired the injury with absorbable suture in a 2-layer intracorporeal running fashion. After the repair was completed, the Foley catheter was irrigated with 100mL of sterile saline. A watertight seal had been created (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

3cm defect visualized at the dome of the bladder during laparoscopic repair.

Figure 3.

View of the laparoscopic bladder repair done in 2 layers of absorbable suture.

This patient was admitted to the hospital for 2 days. He left the hospital with his Foley catheter in place. At a follow-up visit 10 days out from surgery, a cystogram was performed, and the catheter removed when no extravasation of contrast was visualized.

DISCUSSION

Bladder injuries only occur in about 1.5% of all blunt trauma cases. Most of the injuries occur concomitantly with pelvic fractures, 80% of the time, while almost 6% of patients with pelvic fractures will have a bladder injury. Motor vehicle crashes are the most common causes (90%), followed by falls, industrial trauma/pelvic crush injuries, and other blows to the abdomen. Bladder rupture occurs from a blow/injury to the abdomen while the bladder is distended with or without fracture of the pelvis. The dome of the bladder, being the weakest and mobile portion, is the most common area to be affected by blunt trauma to the abdomen.1–4

The most frequent sign of bladder rupture is gross hematuria.1,5 There are often signs of trauma to the pelvis or perineal area, and there may be abdominal distention. If the patient is alert and not intubated, he or she may complain of the inability to urinate, abdominal pain, or suprapubic discomfort. Laboratory studies are nonspecific but may show abnormal electrolytes and an increase in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. However, these laboratory abnormalities are more common in a delayed presentation of intraperitoneal bladder rupture.1,4

If there is suspicion of a bladder injury, the next step is confirmation. A Foley catheter may have already been inserted revealing gross hematuria. This is deferred if there is any blood at the meatus, because a concomitant urethral injury may have occurred.1 Computed tomography is one modality that is used for diagnosis. The advantage of computed tomography is the ability to recognize other intraabdominal trauma and identify all areas of pelvic fracture. The sensitivity of the CT scan is 83% for the diagnosis of bladder trauma. The gold standard for diagnosis of intraperitoneal bladder trauma is retrograde cystogram. After a Foley catheter has been inserted, 300mL to 400mL of contrast is instilled into the bladder under gravity filling while anteroposterior and oblique plain films are taken while the bladder is full.1 Postvoid films are also performed for completion of the examination. Contrast will outline the intraabdominal organs, including the small bowel, paracolic gutters, and around the liver.

Bladder injuries can be characterized into intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal injuries. Extraperitoneal injuries are generally treated with indwelling Foley catheter for about 14 days. If a bony fragment from a pelvis fracture is the cause of the bladder injury, there are reports of operative repair for this cause of an extraperitoneal bladder injury. With an intraperitoneal injury, there are often other intraabdominal injuries; therefore, the bladder injury is repaired during laparotomy. It is repaired in a 2-layer fashion with absorbable suture. The bladder is then drained via a transurethral catheter or suprapubic catheter.6 If the patient is stable, and/or the bladder injury is the only suspected injury, laparoscopy can be a modality used to repair the bladder.

Prior to laparoscopic repair, cystoscopy can help localize the area of injury.7 The most common location of intraperitoneal rupture is at the dome of the bladder, which is easily amenable to repair laparoscopically. However, cystoscopy can help reveal injuries that are not as easy to repair, such as near the bladder neck or ureteral orifice.3

The standard of care in the past has been laparotomy for repair of bladder injuries, because they frequently occur with concomitant intraabdominal injuries.1 However, with the advent of laparoscopy, the repair of an intraperitoneal bladder injury has become a realization. After the workup as described above has been performed, and in a stable patient, laparoscopic repair of the bladder is safe and practical. The appeal of laparoscopy in the stable trauma patient has many advantages, such as shorter length of hospital stay, decreased use of postoperative analgesia, faster return to activities of daily living, and possible decreased cost in the long run, among other things.3 Particularly with laparoscopic bladder repair, the surgeon has the ability to visualize the bladder mucosa and any intravesicular blood clots that may be present, and also has the opportunity to remove clots and achieve hemostasis. Visual magnification, especially in the close quarters of the pelvis, makes laparoscopy an attractive option in this particular situation.7

There are several different techniques for intraperitoneal bladder repair. An open bladder repair commonly uses the 2-layer closure technique. This is reciprocated in the laparoscopic repair as well, as we performed in our case. The other options for closure of intraperitoneal cystostomy include single-layer closure, Endoloop suture for closure, and automatic stapler. Overall, the key to cystostomy closure is a watertight seal without lithogenic properties of the material used for closure, which was problematic with the stapling devices.8–11

At the conclusion of the repair, most authors would propose checking for a watertight seal. This can be performed by instillation of normal saline, indigo carmine, or methylene blue via Foley catheter.3,10,12 Once the repair is confirmed, the laparoscope can be used to confirm there are no other injuries within the abdomen. A urinary catheter is left in place at the conclusion of the procedure as well as a pelvic drain. Generally, patients can be discharged within 1 to 2 days after the repair with removal of the pelvic drain. Follow-up is 10 to 14 days postprocedure for cystogram to check for urinary extravasation. At that time, if no extravasation is present, the urinary catheter can be removed.

It must be stressed that laparoscopic repair of an intraperitoneal bladder injury should only be performed in a stable patient with an isolated bladder injury or minimal other injuries. Laparoscopic repair is not recommended in patients with multiple other injuries, especially other intraabdominal injuries, hemodynamic instability, unstable pelvic fractures, or patients with pelvic hematomas.

CONCLUSION

Laparoscopic repair of the intraperitoneal bladder rupture is a practical alternative to the conventional open repair, especially with the movement towards more minimally invasive surgery. We have proven that laparoscopic repair of a bladder injury can be used safely and effectively even in a trauma patient. The advantages over open repair are indisputable. We advocate its use more frequently in the appropriate patient.

Contributor Information

Tiffany D. Marchand, Department of General Surgery, St. Elizabeth Health Center, Youngstown, Ohio, USA..

Rene Hugo Cuadra, Department of General Surgery, St. Elizabeth Health Center, Youngstown, Ohio, USA..

Daniel J. Ricchiuti, Department of General Surgery, St. Elizabeth Health Center, Youngstown, Ohio, USA..

References:

- 1. Gomez RG, Ceballos L, Coburn M, et al. Consensus statement on bladder injuries. BJU International. 2004;94:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corriere JN, Sandler CM. Diagnosis and management of bladder injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yee DS, Kalisvaart JF, Borin JF. Preoperative cystoscopy is beneficial in selection of patients for laparoscopic repair of intraperitoneal bladder rupture. J Endourol. 2007;10:1145–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gunnarsson U, Heuman R. Intraperitoneal rupture of the urinary bladder the value of diagnostic laparoscopy and repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1997;7:53–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wirth GJ, Peter R, Poletti PA, Iselin CE. Advances in the management of blunt traumatic bladder rupture: Experience with 36 Cases. BJU Int. 2010;106(9):1344–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim FJ, Chammas MF, Varella Gewehr E, Campagna A, Moore EE. Laparoscopic management of intraperitoneal bladder rupture secondary to blunt abdominal trauma using intracorporeal single layer suturing technique. J Trauma. 2008;65:234–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matsui Y, Ohara H, Ichioka K, Terada N, Yoshimura K, Terai A. Traumatic bladder rupture managed successfully by laparoscopic surgery. Int J Urol. 2003;10:278–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Appeltans BMG, Schapmans S, Willemsen PJA, Vergruggen PJEM, Denis LJ. Urinary bladder rupture: Laparoscopic repair. BJU 1998;81:764–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iselin CE, Rohner S, Tuchschmid Y, Schmidlin F, Graber P. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture. Urol Int. 1996;57:119–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poffenberger R. Laparoscopic repair of intraperitoneal bladder injury: A simple new technique. Urology. 1996;47:248–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhanot A, Bhanot A. Laparoscopic repair in intraperitoneal rupture of urinary bladder in blunt trauma abdomen. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:58–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parra RO. Laparoscopic repair of intraperitoneal bladder perforation. J Urol. 1997;151:1003–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]