Surgeons should be aware of splenic torsion as a potential, albeit rare, complication as related to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.

Keywords: Spleen, Torsion, Nissen Fundoplication, Splenectomy

Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication has become a mainstay in the surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease, as it has proved to be a durable, well-tolerated procedure. Despite the safety and efficacy associated with this procedure, surgeons performing this advanced laparoscopic surgery should be well versed in the potential intraoperative and postoperative complications.

Methods:

A case is presented of a rare complication of splenic torsion following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Diagnostic evaluations and intraoperative findings are discussed.

Results:

We present an otherwise healthy 41-year-old woman who underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication 6 years earlier at another medical center and presented with worsening chronic left upper quadrant abdominal pain. She was diagnosed with torsion of the splenic vascular pedicle, resulting in heterogenicity of perfusion with associated hematoma requiring open splenectomy.

Conclusion:

Surgeons should be aware of splenic torsion as a potential, albeit rare, complication related to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease remains a prevalent health concern. Although typically well controlled with medical therapy, surgery is sometimes required, because it addresses the mechanical issues associated with the disease and results in long-term patient satisfaction. One controversial technical factor associated with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication involves division of the short gastric vessels. While debated, short gastric division is favored by many surgeons, because it allows the fundus of the stomach to be wrapped around the esophagus without undue tension. Although rarely encountered, takedown of the short gastric vessels can potentially lead to increased mobility of the spleen and even vascular torsion.

Vascular torsion of a wandering spleen is a rare event and is a result of laxity of the various support structures of the spleen. This laxity can be congenital in origin, such as in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, or acquired. Nonacquired laxity has a predilection for male patients under 10 years old and multiparous women in older age groups.1 Clinical presentation is variable and can range from asymptomatic to acute abdomen when splenic infarction or rupture occurs due to significant vascular torsion.2

We present a patient with splenic torsion resulting in vascular compromise, requiring splenectomy following distant Nissen fundoplication and a minor motor vehicle crash.

CASE REPORT

Our case involves a 41-year-old woman who underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication 6 years earlier at an outside institution for medically refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Unfortunately, the operative report from the previous surgeon was unavailable, because the patient was unaware of the hospital or surgeon's name. Approximately 4 years following her laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, 2 years prior to presentation, the patient was involved in a minor motor vehicle crash and had been experiencing chronic left upper quadrant pain since. Her pain had recently begun to worsen, and she presented to our medical center where a computed tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen showed a change in normal splenic configuration with mild heterogenicity of flow (Figure 1). She was sent home and was subsequently seen in follow-up a few weeks later with worsening acute pain. A repeat CT scan showed interval torsion of the spleen with 90-degree rotation in a clockwise configuration with associated vascular torsion and attenuation of the spleen consistent with congestion and descent of the spleen into the left lower quadrant (Figure 2). Given the patient's degree of pain and radiographic findings of splenic congestion due to vascular torsion, exploration with possible splenectomy was undertaken. The choice of an open procedure by the surgeon was due to the peculiar location of the spleen in the abdomen. Of note, the evening prior to her surgery, the patient experienced an acute increase in her level of pain.

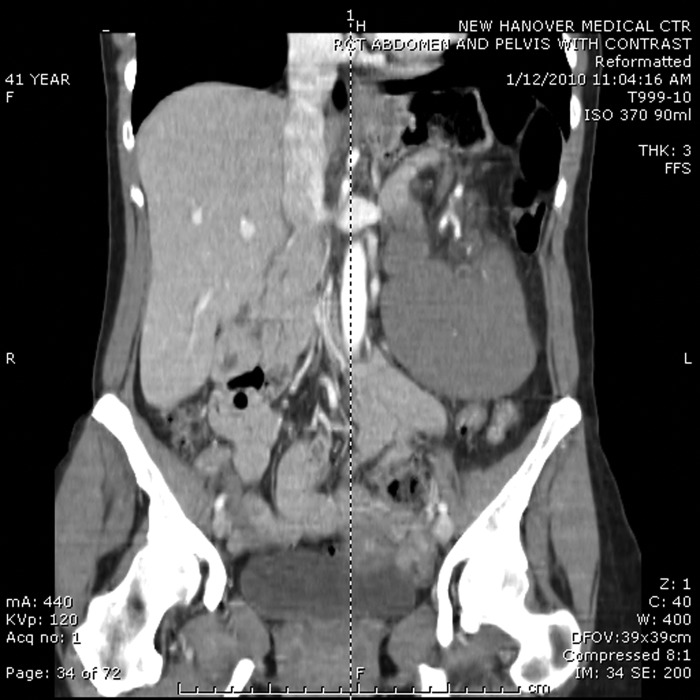

Figure 1.

Reformatted coronal view, CT scan of the abdomen pelvis. Note the nonanatomic location of the spleen in the left lower quadrant and mild heterogenicity of flow noted at the cephalad portion.

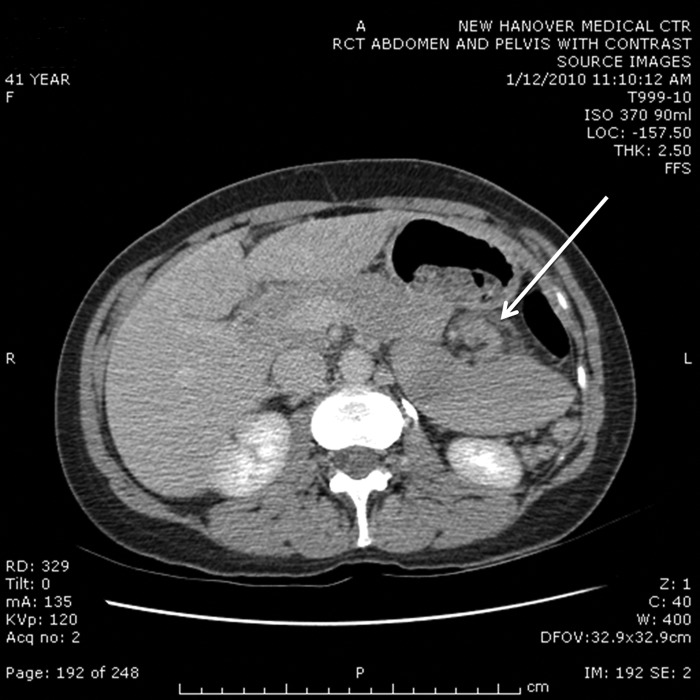

Figure 2.

Axial view, CT scan of the abdomen. Note the nonanatomic position and clockwise rotation of the spleen. The white arrow denotes the characteristic whirl sign, pathognomonic for torsion of the vascular pedicle.

Intraoperatively, a midline laparotomy was performed, and the spleen was found to have descended deep to the transverse mesocolon through the lesser sac into the left lower quadrant. A moderate amount of old blood was noted in the abdomen. The gastrocolic ligament was taken down, and when the spleen was delivered into the wound (Figure 3), splenic rupture was noted on the inferior pole. This was likely the cause of the patient's acute increase in abdominal pain the evening prior to surgery. The spleen was suspended by a pedicle, which was mildly torsed. The spleen itself was also very enlarged and congested but immediately became smaller and pale when detorsion of the vascular pedicle was performed (Figure 4). Given the presence of rupture and the possibility of re-torsion, it was decided to proceed with splenectomy. There were no intraoperative complications.

Figure 3.

Delivery of the spleen into the wound with splenic rupture noted at the inferior pole.

Figure 4.

On delivery of the spleen, the vascular pedicle was de-torsed, and the spleen immediately decongested. A small amount of hemoperitoneum was noted immediately upon entering the abdomen.

DISCUSSION

First appearing in the literature in 1870, wandering spleen, also called splenoptosis, can be difficult to diagnose, and accounts for <0.25% of all indications for splenectomy.2 An exceedingly rare diagnosis, fewer than 500 cases have been reported in the literature as of 2002, and case reports are still accumulating for this rare entity.3 Literature regarding splenoptosis can be found in the pediatric literature as well, citing embryologic or congenitally acquired abnormalities in the ligamentous attachments of the spleen or aberrant development, resulting in nonanatomic placement, (ie, the wandering spleen) with possible subsequent vascular torsion.4 Wandering spleen is found equally in both sexes in patients under the age of 10, but in those diagnosed with wandering spleen older than age 10, females outnumber males by approximately 7:1.5 The spleen itself is normally fixed by several ligamentous attachments to various intraabdominal structures. These include the splenorenal, gastrosplenic, splenocolic ligaments, as well as attachments to the lateral abdominal wall. Congenital or acquired laxity of these ligaments, as in the variable takedown of the gastrosplenic ligament containing the short gastric vessels during elective laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, can lead to increased mobility of the spleen and predispose to torsion.

To obtain adequate tension-free fundoplication of the gastric fundus, current expert opinion in North America advocates routine division of the short gastric arteries, which lie within the gastrosplenic ligament.6 At the present time, evidence from 5 randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of short gastric vessel division on outcomes following laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery indicate that division should be avoided if adequate tension-free fundoplication can be performed without division of the short gastric arteries.6 This recommendation is based on the reports of increased operating time, increased flatus production and epigastric bloating, and decreased ability to vent air from the stomach associated with short gastric vessel division if it is possible to construct a fundoplication without undue tension.6 None of the randomized trials evaluating short gastric division reported any major complications relating to division and no incidence of wandering spleen, although one patient had to have a reoperation for bleeding from the short gastric vessel.7 Interestingly, a study by Szor and colleagues8 on cadavers reported that gastric fundus tension did not correlate with any anatomic parameters and that short gastric vessel division had a significant effect on decreasing tension.

Our patient is being presented here because of splenic torsion of a wandering spleen as a possible complication of previous laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and to our knowledge is the first reported case. Unfortunately, we do not have the operative report from the original laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, and therefore cannot comment on the laxity of the ligaments, the reason for the short gastric division, or definitive causality of this resulting in the wandering spleen. In our patient, it was noted at the time of operation that the short gastric vessels were indeed divided at the time of the prior anti-reflux procedure, and, in combination with minor trauma, may have predisposed this patient to the wandering spleen phenomenon with nonanatomic, caudal displacement of the spleen and subsequent vascular torsion. The characteristic whirl sign can be seen in Figure 2 in the area of the splenic vascular pedicle, indicative of torsion.

Management of wandering spleen has been primarily surgical in the multiple case studies in the literature and has consisted of splenectomy (both open and laparoscopic) as well as splenopexy in cases without splenic rupture and normal sized spleens. One small case study in 2004 demonstrated successful laparoscopic splenopexy using a Vicryl mesh bag.9 Splenic preservation in cases of wandering spleen without rupture or infarction avoids the risk of overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis, and a laparoscopic approach allows for shorter hospital length-of-stay and decreased postoperative pain. In our patient, because of the intraoperative findings of splenic rupture, splenectomy was performed. At the time of this writing, the patient is doing well postoperatively and has received postsplenectomy triple vaccinations against encapsulated organisms in concordance with the current guidelines.

CONCLUSION

Splenic torsion resulting from laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is a rarely reported complication and may be related to division of the short gastric vessels. Surgeons performing anti-reflux surgery should be aware of this potential complication.

Contributor Information

Khoi Le, South East Area Health Education Center, Department of Surgery, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, North Carolina, USA..

Devan Griner, South East Area Health Education Center, Department of Surgery, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, North Carolina, USA..

William W. Hope, South East Area Health Education Center, Department of Surgery, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, North Carolina, USA..

Darryl Tackett, South East Area Health Education Center, Department of Surgery, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, North Carolina, USA..

References:

- 1. Sodhi KS, Saggar K, Sood BP, Sandhu P. Torsion of a wandering spleen: acute abdominal presentation. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Misawa T, Yoshida K, Shiba H, Kobayashi S, Yanaga K. Wandering spleen with chronic torsion. Am J Surg. 2008;195:504–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Satyadas T, Nasir N, Bradpiece HA. Wandering spleen: case report and literature review. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2002;47:512–514 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vazquez JL, Montero M, Diaz F, Muguerza R, Paramo C, Rodriguez-Costa A. Acute torsion of the spleen: diagnosis and management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:153–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dawson JH, Roberts NG. Management of the wandering spleen. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:441–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Kohn GP, Reardon PR, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD. Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 24:2647–2669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang H, Watson DI, Lally CJ, Devitt PG, Game PA, Jamieson GG. Randomized trial of division versus nondivision of the short gastric vessels during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: 10-year outcomes. Ann Surg. 2008;247:38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Szor DJ, Herbella FA, Bonini AL, Moreno DG, Del Grande JC. Gastric fundus tension before and after division of the short gastric vessels in a cadaveric model of fundoplication. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:539–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cavazos S, Ratzer ER, Fenoglio ME. Laparoscopic management of the wandering spleen. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:227–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]