SYNOPSIS

Objective

We identified trends in the receipt of preventive health care by adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities by type of residential setting.

Methods

We used data from the 2008–2009 collection round of the National Core Indicators (NCI) program. Participating states drew random samples of adults receiving developmental disabilities services. The study was observational, with both self-report and report by proxy. Once the random samples were drawn in each state, data were collected using the NCI Adult Consumer Survey. Trained interviewers administered the survey in person.

Results

The likelihood of a person receiving preventive care procedures was related to age, level of intellectual disability, mobility, health status, and state. Type of living arrangement also affected whether a person received these health services, even after controlling for state, level of disability, and other personal characteristics. In general, people living with parents or relatives were consistently the least likely to receive preventive health exams and procedures.

Conclusion

With growing numbers of adults being served in the family home, educational and policy-based efforts to ensure access to preventive care are increasingly critical.

Recent years have seen an increased focus on health-care provision, access, and quality for our nation. Affordable and equitable health care is a national priority. Likewise, increased focus is on the quality of and access to health care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/DD). In 2002, a landmark report from the Surgeon General first addressed the need to improve the health of individuals with mental retardation and emphasized the importance of preventive services.1 In 2005, the Surgeon General published a Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities.2 The Healthy People 2020 initiative specifically addresses the barriers that people with ID/DD face in accessing health-care services.3 Preventive health care and healthy behaviors are receiving particular attention. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funds state-based programs that address needs specific to the ID/DD community pertaining to overall health, inadequate access to health care, smoking, and physical activity initiatives.4

Several factors underscore the importance of preventive health care for the ID/DD population. With increased life expectancy, people with ID/DD face the same health risks as the general population and the same or higher rates of common chronic health conditions.5–7 Campbell et al.8 found that aging people with ID/DD experienced earlier onset of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension. Likewise, Reichard and Stolzle9 reported a significantly higher prevalence of chronic conditions (i.e., diabetes, asthma, arthritis, cardiac disease, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and stroke) among adults with cognitive limitations. Furthermore, people with ID/DD tend to be disproportionately poor10 and, therefore, share the same health-care disparities as those in the general population who are living in poverty. In other words, there is a correlation between wealth and health.11

As the life expectancy of people with ID/DD grows and the landscape of service provision changes, more and more adults with ID/DD are living independently or with family. From 1999 to 2009, the number of service recipients living with family members increased by 68.7%.12 In June 2009, an estimated 57.7% of all people receiving ID/DD residential services were living with family members. Several studies have documented the benefits of living in less restrictive environments. Lakin and Stancliffe13 noted that there are associated increases in personal freedom, self-determination, and personal choice, and a decrease in staff control and loneliness, among those living in less restrictive environments. Their study supported previous findings14,15 that community living enhances participation in community activities and fosters community integration. In fact, research has demonstrated that different types of residences are associated with a variety of individual outcomes in consumer choice, community inclusion, and satisfaction.13,15–17

The shift toward home and community-based residential supports brings with it the challenge of having to navigate community health-care resources. One characteristic of institutions is the centralization of care—including routine health care—and a regulatory structure that requires (and monitors) the provision of these services. While advancements in the provision of residential services and supports in the community have expanded opportunities and improved quality of life for people with ID/DD, the provision of adequate health-care services is still a concern.18 For example, Lewis et al.19 described the inadequate access to medical and dental health care experienced by adults with ID/DD living in community care facilities in Los Angeles, California. Previous studies showed that people living in the community are less likely to receive preventive health-care services than people in institutional environments.19–25 Similarly, Emerson26 found that English adults with ID who do not use ID services experience significantly less access to preventive health services (e.g., dentist, eye test, and hearing test) than adults who live in supported accommodations. Unfortunately, almost all of these studies share common weaknesses, such as small sample sizes, convenience samples, and no adjustment for the level of disability. This latter consideration is important because the level of disability may affect receipt of preventive care and because level of disability tends to vary by residence type.

A notable exception was research on people with ID/DD based on the 1994/1995 Disability Supplement to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS-D). The NHIS-D sample included 3,076 people who could be identified as having ID/DD who were living in homes of their own or with family members.27 Some of the findings of resulting research included that people with ID/DD reported having significantly poorer overall health than the general public and a significantly higher rate of use of psychotropic medication (10.5% vs. 2.4%). Adults with ID/DD were significantly more likely to report having unmet needs for health care, mental health care, prescription medication, and dental care than those with no functional limitations.27 Controlling for age, gender, economic status, race, overall health status, and health coverage status, people with ID/DD had more short-term hospital stays and doctor visits in the past 12 months and days of activity restriction in the past two weeks. Unfortunately, while the NHIS-D provided rich descriptions of health status and needs of people with ID/DD, subsequent years of the NHIS have not included variables needed to reliably identify people with ID/DD in their samples, leaving us with a one-time snapshot that is now nearly 20 years old.

Showing whether differences in the likelihood of receiving preventive care based on different residential arrangements truly exist when other factors such as level of disability are accounted for, and quantifying those differences if they do exist, will help policy makers, state DD agencies, and care providers to focus their efforts and resources, while targeting those adults with ID/DD who are at the highest risk of not receiving preventive health-care services. Our study addresses some of the weaknesses of existing research. We used a large non-convenience national sample to explore whether people living with families or on their own are less likely to receive preventive health care, while also controlling for level of disability and other individual characteristics.

METHODS

Instrument

Our study utilized data from the 2008–2009 collection round of the National Core Indicators (NCI) program, which includes approximately 100 performance and outcome indicators that aim to measure and aid in improving system performance of state DD authorities. Indicators are measured by multiple data sources. The primary data source for the NCI program is the Adult Consumer Survey—a survey specifically designed to be administered in a face-to-face interview with adults with ID/DD and people involved in their lives. The NCI program is a voluntary collaboration between the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services, the Human Services Research Institute, and state developmental disability agencies of participating states. No NCI data are collected in nonparticipating states.28

The Adult Consumer Survey consists of three sections: the background section, where characteristics of the person being interviewed are recorded; section I where only the individual's responses are allowed; and section 2, where proxy responses are also allowed. All the variables in this study were drawn from the background section.

Sampling

The goal of the NCI program is for each participating state to draw a random sample of at least 400 individuals from everyone receiving services in the state. Sample selection is randomized so that every person in the state or service area that meets the criteria has an equal opportunity to be interviewed. Samples are usually based on the criteria that individuals be 18 years of age or older and receive at least one service besides case management. There are no a priori exclusion criteria.

Almost all states met this goal. There were some exceptions, with several states opting to exclude some segments of the served population (e.g., those residing in institutions), not succeeding in conforming to a perfectly random sampling scheme, or falling slightly short of the 400 interviews. To account for state sampling differences, we statistically controlled (adjusted) for the state in our models.

The overall response rate for the background section was almost 100%, though the response rate for any given item in the background section may be lower. Our data consisted of 11,569 adult surveys from all 20 states that participated in the 2008–2009 NCI program and collected Adult Consumer Survey data (i.e., Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Wyoming).

Variables

Among other indicators in the background section of the Adult Consumer Survey, the NCI program includes questions on receipt of several preventive health-care procedures. These questions were used to create our dependent variables, which comprised physical exam in past year, dental visit in past year, vision screening in past year, hearing exam in past five years, influenza vaccine in past year, pneumonia vaccine (ever), Papanicolaou (Pap) test in past three years for women aged ≥18 years, mammogram in past two years for women aged ≥40 years, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test in past year for men aged ≥50 years, and colorectal cancer screening in past year for people aged ≥50 years. All dependent variables were binary (yes/no). These items, which were gathered in the background information section of the instrument, are typically answered from administrative records rather than from the direct interview. The availability of information varies depending upon specific state procedures and location of the interviews.

The completeness of data on these items was, unfortunately, not ideal, particularly for some of the procedures (with a relatively high percentage of “don't knows”). Percentages of “don't know” responses ranged from approximately 7% for receipt of physical exam to 45% for pneumonia vaccination. It is likely that in most cases, a response of “don't know” indicates a negative response—that is, if there is no record of a procedure, it is likely that the procedure was not performed. However, we decided to err on the side of caution and exclude “don't knows” from the analysis of each item.

We investigated whether individuals for whom “don't know” responses were recorded differed from individuals who had valid medical information. We found no significant differences in terms of most of the personal characteristics tested. The one noteworthy difference was that people with “don't know” responses were more likely to live on their own or with their parents.

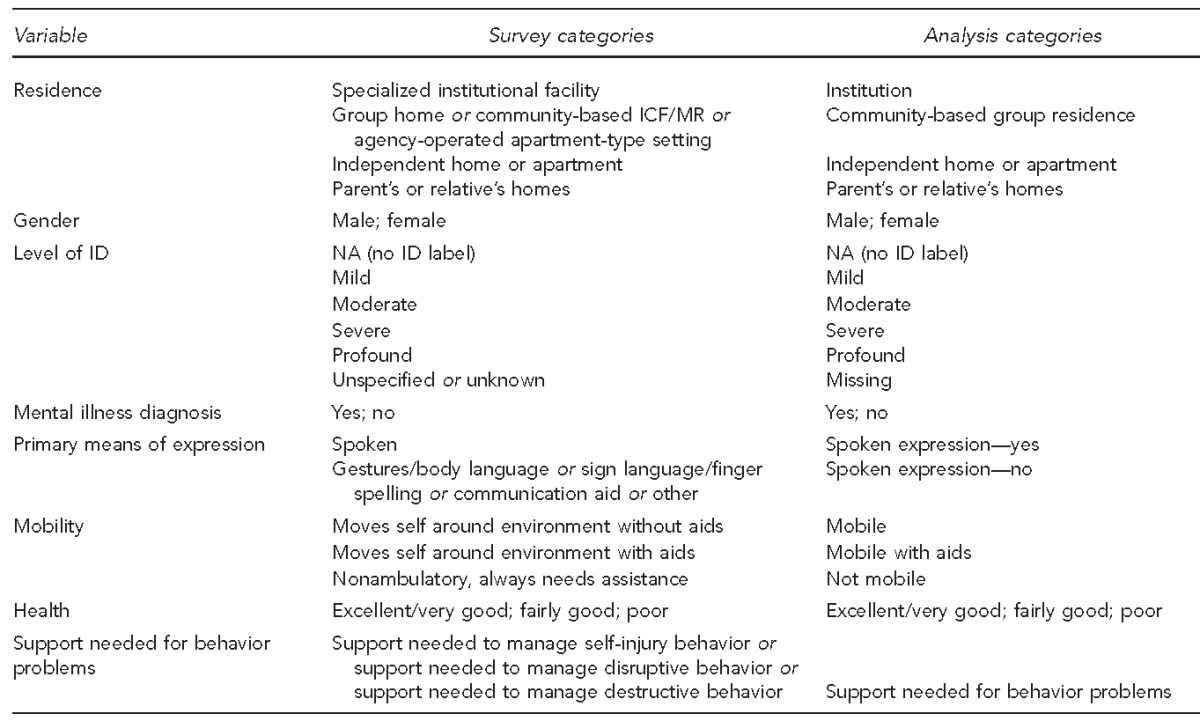

The Adult Consumer Survey also collects background information on the place of residence and personal characteristics. We used that information to create the following residential categories: institution, community-based group residence, independent home or apartment, and parent's or relative's home. The personal characteristics used for adjustment in our models consisted of gender, level of ID, mobility, diagnosis of mental illness, age, health status, primary means of expression, and support for behavior problems. Operational definitions of residence and personal characteristics can be found in the (Figure. (More detailed definitions of constructs used by the survey are available from the authors by request.)

Figure 1.

Operationalization of independent variables used in a study of place of residence and preventive health care for adults with ID/DD receiving services in 20 states: 2008–2009a

aData used for the study were from the 2008–2009 collection round of the National Core Indicators Adult Consumer Survey.

ID = intellectual disability

DD = developmental disability

ICF/MR = immediate care facility for individuals with mental retardation

NA = not applicable

Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS® version 18.29 We performed a series of logistic regressions, starting with analyses examining the relationship between where people resided and their probability of receiving various preventive health-care procedures, controlling for state only. We then conducted another series of logistic regressions, examining the same relationship, but controlling for both state and degree of disability.

RESULTS

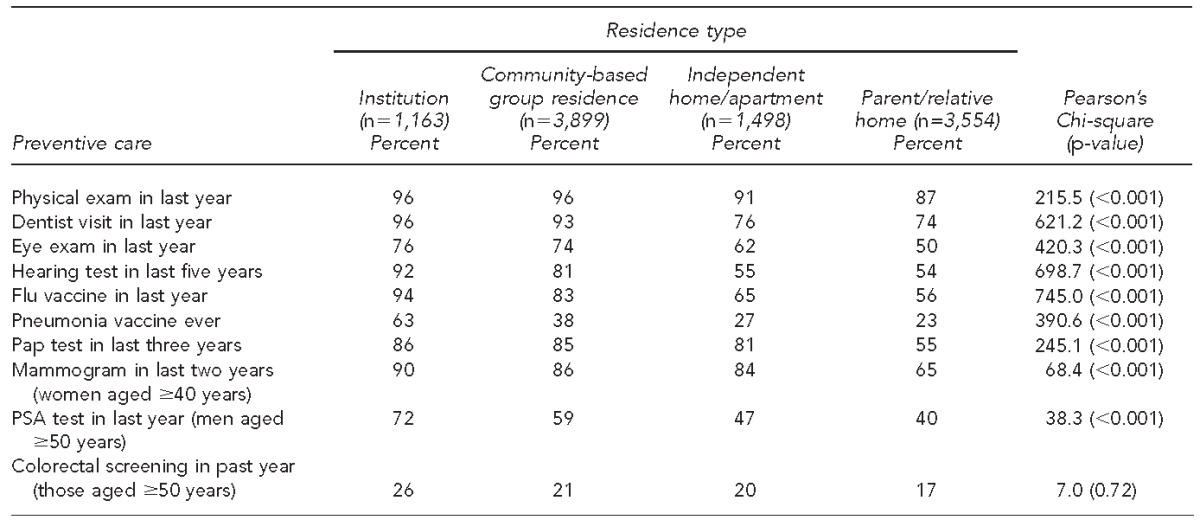

Table 1 presents observed percentages of receipt of preventive health-care procedures by people in -different types of residential arrangements, across our entire sample. People in our sample living in a parent's or relative's home were least likely to receive preventive care, while those living in institutions were most likely to receive such care. The difference was particularly large for vaccination rates (flu and pneumonia), hearing and vision exams, and cancer screenings (i.e., Pap test, mammogram, and PSA test). For example, of people living with families, only 74% had a dental visit in the past year, 50% had a vision exam in the past year, and 54% had a hearing exam in the past five years, compared with 96%, 76%, and 92%, respectively, of those living in institutions. With the exception of mammography, Pap tests, and eye exams, the percentage of people living in independent homes who had received preventive exams was only slightly higher than people living with parents/relatives. On the other hand, with a few exceptions, people living in community-based group residences were only slightly less likely to receive preventive care than people living in institutions (e.g., 93% had a dental visit, 74% had a vision exam, and 81% had a hearing exam).

Table 1.

Rates of preventive care by residence type, in a study of place of residence and preventive health care for adults with ID/DD receiving services in 20 states: 2008–2009a

aData used for the study were from the 2008–2009 collection round of the National Core Indicators Adult Consumer Survey.

ID = intellectual disability

DD = developmental disability

Pap = Papanicolaou

PSA = prostate-specific antigen

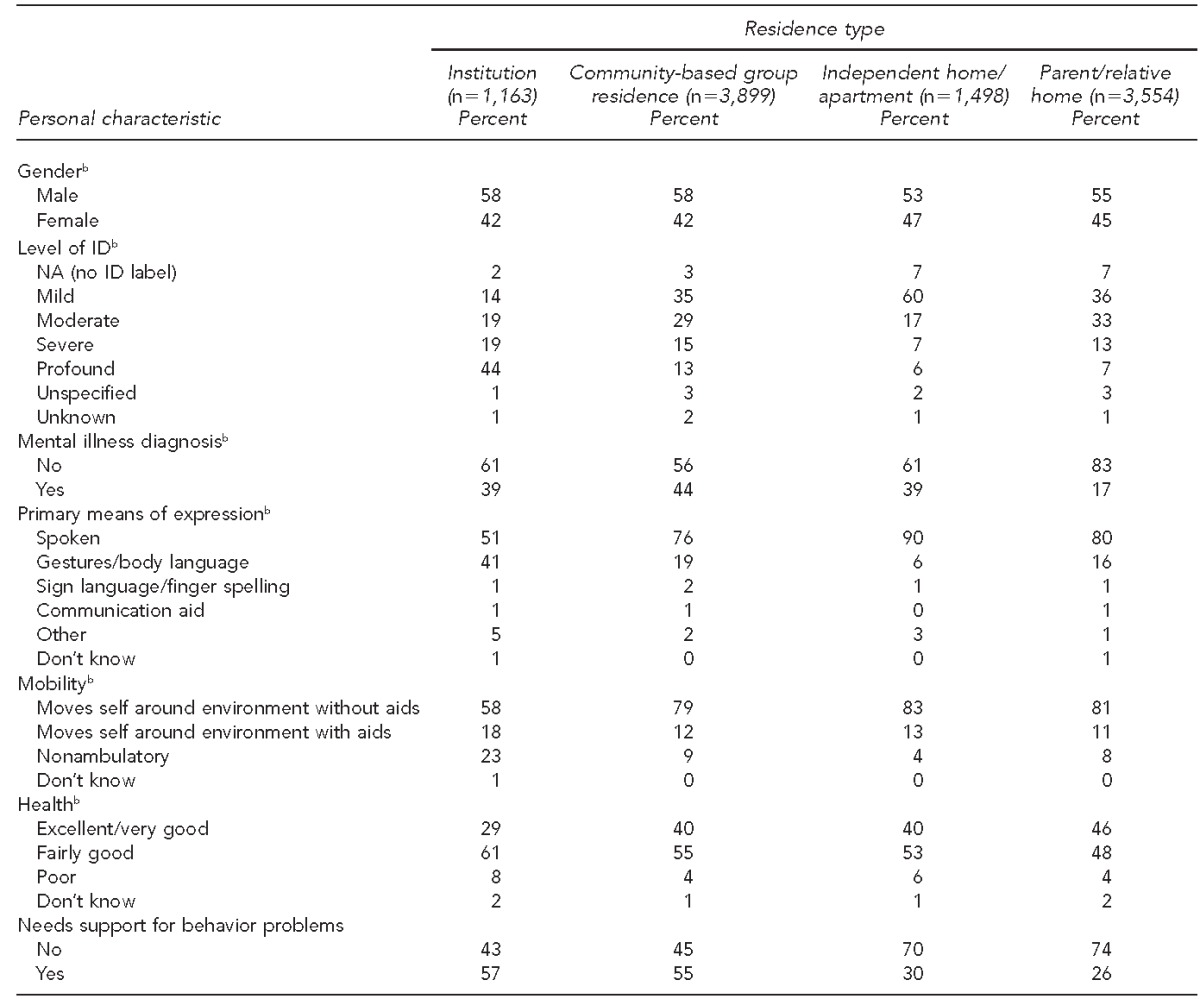

Table 2 shows how people in various residential arrangements differed in terms of their personal characteristics and level of disability. Individuals living in institutions were more likely to be labeled as having profound ID, more likely to be nonverbal, more likely to be either nonambulatory or need aids for mobility, and less likely to be in excellent or very good health. People living in independent homes or apartments were slightly more likely to be female, more likely to have the label of mild ID, more likely to be verbal, and more likely to not need support for behavioral problems. People living in a relative's home were least likely to have a diagnosis of mental illness or need support for behavioral problems. They were also most likely to be in excellent or very good health. Those living in Tablecommunity-based group residences were similar to people living in a family home in terms of ID label, means of expression, and mobility, and similar to people living in institutions in terms of needing support for behavior problems.

Table 2.

Personal characteristics by type of residence, in a study of place of residence and preventive health care for adults with ID/DD receiving services in 20 states: 2008–2009a

aData used for the study were from the 2008–2009 collection round of the National Core Indicators Adult Consumer Survey.

bStatistically significant differences between residential types (p<0.01)

ID = intellectual disability

DD = developmental disability

NA = not applicable

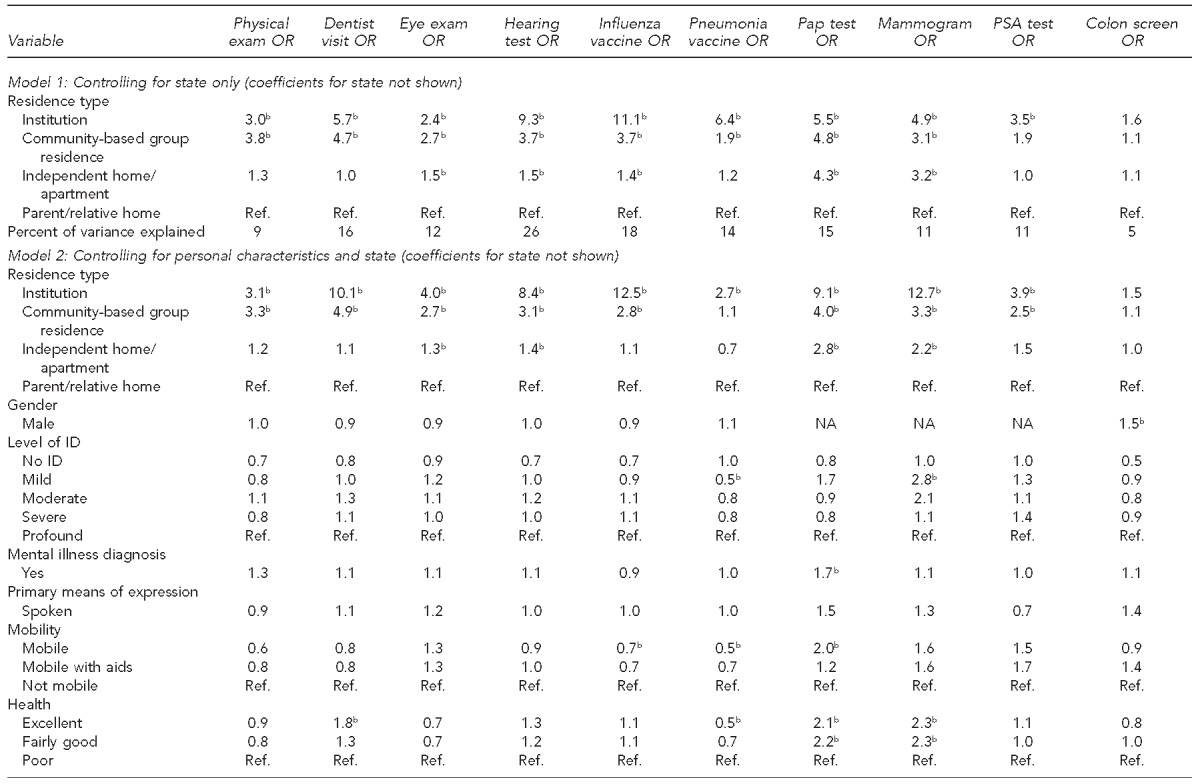

Model 1 of Table 3 presents the results of logistic regression, controlling only for state. The coefficients for states are not shown, but state is a statistically significant factor. Parent's or relative's home was the reference category; thus, all other residence types were compared with living in a relative's home. People living in an institution were anywhere from 2.4 times (vision exam) to 11.1 times (flu vaccine) as likely to receive preventive care as those living with family (with the exception of colorectal cancer screening). Living in a community-based residence raises the odds of receiving preventive care as well—those living in such residential arrangements were from 1.9 times (pneumonia vaccine) to 4.8 times (Pap test) as likely to receive preventive care as those living in a family home. In addition, those living independently in their own home or apartment had significantly greater access to several forms of preventive health care than individuals living with a family member, with odds ratios (ORs) ranging from 1.4 (flu vaccine) to 4.3 (Pap test).

Table 3.

Logistic regression models controlling for state and for both state and personal characteristics, in a study of place of residence and preventive health care for adults with ID/DD receiving services in 20 states: 2008–2009a

aData used for the study were from the 2008–2009 collection round of the National Core Indicators Adult Consumer Survey.

bp<0.01

ID = intellectual disability

DD = developmental disability

OR = odds ratio

Pap = Papanicolaou

PSA = prostate-specific antigen

Ref. = reference group

Model 2 in Table 3 presents logistic regressions in which we controlled for both state and personal characteristics, including level of disability and age. Characteristics associated with receiving preventive care included mobility, health status, age, and, in some cases, level of ID, presence of mental illness, and male gender. The effect of disability is not always in the expected direction. For example, women with mild ID were 2.8 times as likely to receive a mammogram, and people with a diagnosis of mental illness were more likely to receive a Pap test. By contrast, women who were mobile were twice as likely to have had a Pap test as women with mobility limitations. In addition, males were 1.5 times as likely to receive a colorectal cancer screening as females.

After controlling for personal characteristics and state, the ORs for access to preventive health care were still significantly different for people in different types of residences. When personal characteristics and state were accounted for, people residing in institutions were even more likely to have had a dental visit and a mammogram compared with people living in relatives' homes (dental visit: OR=10.1 [Table 3, Model 2] compared with OR=5.7 [Table 3, Model 1] when only state was controlled for; mammogram: OR=12.7 [Table 3, Model 2] compared with OR=4.9 [Table 3, Model 1] when only state was controlled for). On the other hand, the odds of having received a pneumonia vaccine decreased for people living in institutions vs. people living with parents or relatives (OR=2.7 after controlling for both personal characteristics and state compared with OR=6.4 after controlling for state only).

DISCUSSION

Several important results emerged from our analysis. We verified that adults with ID/DD living in different residential arrangements differ in terms of personal characteristics, such as age, level of ID, and mobility, and that some of these personal characteristics affect the likelihood of an individual receiving preventive care. In particular, age, level of ID, mobility, and health status seem to have an effect on the receipt of preventive health care. This relationship is not unexpected, in part because some of these characteristics are risk factors for disease, and people with more fragile health conditions may be more likely to access basic health services. We also confirmed our primary hypothesis that even after controlling for disability, a person's living environment has an effect on whether he or she receives standard preventive care procedures. With the exception of pneumonia vaccine, controlling for disability had the effect of increasing the odds of receiving preventive exams for people living in more restrictive environments. The opposite was true for pneumonia vaccine—this result is likely due to the fact that people living in institutions tend to have more of those characteristics related to risk factors that are indicators for the vaccine (such as older age and mobility problems). Regardless of the magnitude of the effect, people living with their families—and, to a somewhat lesser degree, those living in their own homes—are consistently less likely to receive preventive health care.

This last finding is important given the changing patterns of service delivery in the United States. As noted previously, current figures show that people with ID/DD are increasingly more likely to live in their family homes rather than in traditional group settings. At the same time, states are expanding in-home supports to help meet the needs of individuals who are living with families and who choose to live independently, as well as implementing systems for individuals and families to manage their own supports through participant-directed options. Promoting choice and person-centered supports comes with an added responsibility to ensure that individuals and families are informed about and have the necessary supports to access health care (e.g., health record keeping, coordination, transportation, advocacy, and emotional and physical support)—services that traditionally have been overseen by residential service providers.

However, our findings suggest that people living in family homes or their own homes are less likely to access many basic preventive health-care services. Some of the possible reasons include lack of accessible and clear information, difficulty finding qualified physicians willing to provide services, and the lack of needed supports and accommodations to access health care when it is available. Previous research has documented that health-care barriers for people with ID/DD include individual factors (e.g., fear of specific procedures or of seeing a provider, lack of communication with providers, and lack of knowledge about health and prevention), systemic barriers (e.g., difficulty accessing specialty care; difficulty finding providers experienced in meeting people's health-care needs; and lack of care coordination, continuity, and consistency), and financial barriers (e.g., people with ID/DD cited cost as a factor in delaying or not accessing care; discrepancies between public and privately funded health care and lack of insurance are also barriers).30

Limitations

Our study had several important limitations. Foremost of them is the accuracy and availability of health-care information—an issue not unique to our research, but one we were careful to address. Formal services and provider-based residential arrangements may be more likely to keep written records of receipt of preventive health care than families or individuals themselves. Thus, it is possible that individuals living with families are reported to have lower rates of procedures in part due to inaccurate recall or less structured health record keeping. To minimize the potential effect of this information disparity on our results, we excluded all responses of “don't know” from the denominators, even though in most cases, a response of “don't know” probably means “no” (i.e., if a person receiving services was not recorded to have had the exam, he or she probably did not receive it). Unless a “don't know” response almost always means “yes,” it is highly unlikely that recall or record-keeping problems account for the magnitude of differences observed.

Finally, it should be noted that while each state strives to select a representative random sample of adults served, some states were more successful at meeting this goal than others. A few states exclude certain segments of the population, most often those in institutional settings. We sought to control for any sampling differences between states by including state in our logistic regression models. Only adults actively receiving services are included in state samples. A large population of people living with families is waiting for services and was not included in the current study. This population may be different from people living with families and receiving services both in terms of level of disability and access to preventive health care. In this context, it is notable that Emerson26 found that adults with ID who do not use formal disability services have less access to preventive health services than adults who do use ID services, such as supported accommodation.

There are, of course, other potential factors that our analysis could not address. First is the matter of choice. People (or their family) living in more independent settings may be making a conscious choice about not receiving preventive care, while people living in more controlled settings may not have that option. Decisions about whether to obtain preventive care may also be related to past experiences with health-care providers, lack of accurate information, and feelings of anxiety. Secondly, as in almost all studies on utilization of health care, there is an inherent difficulty in linking the care with the outcomes. In other words, just because someone received a vision exam does not necessarily mean that he or she will have better vision outcomes in the future. Therefore, we did not attempt to draw definitive conclusions that people who received the preventive care services will have better dental or medical outcomes. However, if recommendations for preventive care procedures are made because of supposed benefits, then it is clear that people not accessing those services are at a disadvantage. It is especially worrisome, therefore, that the rates of receipt of some preventive care exams (e.g., colorectal cancer screenings) are low, regardless of where the individual resides.

CONCLUSION

Policy makers should pay careful attention to what preventive care supports are recommended in the course of service plan development and monitoring for people with ID/DD. Data suggest that efforts should be strengthened to improve preventive health-care access for people living at home with family and those living independently. For example, community-based providers could be encouraged to organize inoculation opportunities and to publicize free or low-cost options. Furthermore, efforts need to be made to ensure that people transitioning from institution to community-based settings maintain access to care. Returning to a more institutional style service delivery system as a means of ensuring preventive health-care access is not an option; instead, more effective supports need to be put in place that ensure that people living in integrated community settings have the choice and ability to receive quality preventive health care in a timely fashion. Recent public health programs and policies such as the Affordable Care Act31 provisions for prevention and preventive care and Surgeon General's National Prevention Strategy32 afford an environment that is particularly favorable to such initiatives.

Footnotes

The Human Services Research Institute (HSRI) employs several of the authors. HSRI coordinates the National Core Indicators program and receives a fee from participating states. Charles Moseley is employed by the National Association of State Directors of Disabilities Services, which is the co-holder of the copyright of the National Core Indicators with HSRI. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Preparation of this article was supported by grant #H133G080029 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, U.S. Department of Education (federal funds for this three-year project total $599,998, 99.5% of the total program costs, with 0% funded by nongovernmental sources). This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (US); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Closing the gap: a national blueprint for improving the health of individuals with mental retardation. Report of the Surgeon General's Conference on Health Disparities and Mental Retardation. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Surgeon General, Department of Health and Human Services (US). Washington: HHS; 2005. [cited 2011 Aug 22]. Surgeon General's call to action to improve the health and wellness of persons with disabilities. Also available from: URL: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/disabilities/index.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (US). Healthy People 2020. [cited 2011 Aug 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Disability and health: funded state programs. [cited 2011 Aug 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/programs.html.

- 5.Hayden MF, Kim SH. Health status, health care utilization patterns, and health care outcomes of persons with intellectual disabilities: a review of the literature. Policy Res Brief. 2002;13:1–18. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2005)43[175:HSUPAO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traci MA, Seekins T, Szalda-Petree A, Ravesloot C. Assessing secondary conditions among adults with developmental disabilities: a preliminary study. Ment Retard. 2002;40:119–31. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0119:ASCAAW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voelker R. Improved care for neglected population must be “rule rather than exception”. JAMA. 2002;288:299–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell ML, Sheets D, Strong PS. Secondary health conditions among middle-aged individuals with chronic physical disabilities: implications for unmet needs for services. Assist Technol. 1999;11:105–22. doi: 10.1080/10400435.1999.10131995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichard A, Stolzle H. Diabetes among adults with cognitive limitation compared to individuals with no cognitive disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;49:141–54. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-49.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Disability Statistics and Demographics (StatsRRTC). 2004 disability status reports. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JP. Healthy bodies and thick wallets: the dual relation between health and economic status. J Econ Perspect. 1999;13:145–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakin KC, Larson S, Salmi P, Webster A. Residential services for persons with developmental disabilities: status and trends through 2009. Research and Training Center on Community Living: National Residential Information Systems Project. [cited 2011 Aug 22]. Available from: URL: http://rtc.umn.edu/risp09.

- 13.Lakin KC, Stancliffe RJ. Residential supports for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:151–9. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howe J, Horner RH, Newton JS. Comparison of supported living and traditional residential services in the state of Oregon. Ment Retard. 1998;36:1–11. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(1998)036<0001:COSLAT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stancliffe RJ, Keane S. Outcomes and costs of community living: a matched comparison of group homes and semi-independent living. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2000;25:281–305. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakin KC, Doljanac R, Byun S, Stancliffe R, Taub S, Chiri G. Choice-making among Medicaid HCBS and ICF/MR recipients in six states. Am J Ment Retard. 2008;113:325–42. doi: 10.1352/2008.113.325-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stancliffe RJ, Lakin KC, Taub S, Chiri G, Byun SY. Satisfaction and sense of well-being among Medicaid ICF/MR and HCBS recipients in six states. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;47:63–83. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-47.2.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewitt A, Larson S. The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: issues, implications, and promising practices. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:178–87. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis MA, Lewis CE, Leake B, King BH, Lindemann R. The quality of health care for adults with developmental disabilities. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:174–84. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bershadsky J, Kane RL. Place of residence affects routine dental care in the intellectually and developmentally disabled adult population on Medicaid. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5 Pt 1):1376–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon RM, Seltzer MM, Krauss MW. The aftermath of parental death: changes in the context and quality of life. In: Schalock RL, editor. Quality of life. Vol 2: application to persons with disabilities. Washington: American Association on Mental Retardation; 1997. pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krahn GL, Hammond L, Turner A. A cascade of disparities: health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12:70–82. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimmer JH, Braddock D, Marks B. Health characteristics and behaviors of adults with mental retardation residing in three living arrangements. Res Dev Disabil. 1995;16:489–99. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(95)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roush SE, Fresher-Samways K, Stolgitis J, Rabbitat J, Cardinal E. Self- and caregiver-reported experiences of young adults with developmental disabilities. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2007;6:53–73. doi: 10.1300/J198v06n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedman RI, Chassler D. Physical and behavioral health of adults with mental retardation across residential settings. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:401–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerson E. Health status and health risks of the “hidden majority” of adults with intellectual disability. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;49:155–65. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-49.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson SA, Lakin KC, Anderson L, Kwak N, Lee JH, Anderson D. Prevalence of mental retardation and development disabilities: estimates from the 1994/1995 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplements. Am J Ment Retard. 2001;106:231–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Human Services Research Institute; National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services. National Core Indicators. [cited 2012 May 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.nationalcoreindicators.org.

- 29.IBM/SPSS Inc. SPSS™: Version 18. Chicago: IBM/SPSS Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson S, Anderson L, Doljanac R. Access to health care. In: Nehring W, editor. Health promotion for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities: disabilities: the state of scientific evidence. Washington: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2005. pp. 129–84. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Pub. L. No. 111-148 (March 2010)

- 32.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General (US) National Prevention Strategy. [cited 2012 May 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/initiatives/prevention/index.html.