Abstract

We describe an online narrative and life review education program for cancer patients and the results of a small implementation test to inform future directions for further program development and full-scale evaluation research. The intervention combined three types of psycho-oncology narrative interventions that have been shown to help patients address emotional and existential issues: 1) a physician-led dignity-enhancing telephone interview to elicit the life narrative and delivery of an edited life manuscript, 2) life review education, delivered via 3) a website self-directed instructional materials and expert consultation to help people revise and share their story. Eleven cancer patients tested the intervention and provided feedback in an in-depth exit interview. While everyone said telling and receiving the edited story manuscript was helpful and meaningful, only people with high death salience and prior computer experience used the web tools to enhance and share their story. Computer users prodded us to provide more sophisticated tools and older (>70 years) users needed more staff and family support. We conclude that combining a telephone expert-led interview with online life review education can extend access to integrative oncology services, are most feasible for computer-savvy patients with advanced cancer, and must use platforms that allow patients to upload files and invite their social network.

Keywords: Narrative medicine, life review, cancer patients, aging and cancer, life review education, eHealth

Introduction

Cancer is stark reminder of human mortality.1, 2 Treatments mitigate physical pain and increase survivorship, but may increase death anxiety.3 In fact, existential pain (loss of dignity, autonomy, purpose, and hope) contributes more to a wish for hastened death than physical pain4, 5 and drives existential interventions.

Existentialism

Existentialism is an antidote to alienation associated with the scientific rationalism that advances treatments, an extended lifespan, and death denial.6 According to Kierkegaard, “We either live as though we could not die and never really live, or we live fully in the face of nonbeing.”7 While imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp, Frankl incorporated existentialism into Logotherapy which focuses on making meaning of suffering and living with more purpose.8 Existentialism underlies humanizing death and dying,9 research on growth in the face of illness, 5, 10, 11, 12, 13 and narrative-based psycho-oncology interventions,. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 16, 19, 20

Life and Illness Narratives

Life review and illness narratives encourage living fully within the shadows of “mortal time.” 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Life review is a systematic process that promotes Erikson’s later lifespan stages of generativity (legacy) and life integration by focusing on values, accomplishments, relationships, lessons learned through adversity, what needs to be resolved. 26, 27, 28, 29 Cancer (or illness) narratives focus on patients’ experience from diagnosis through survivorship and can reestablish a sense of order and help identify problems, solutions and resources.25, 30, 31, 32 Narratives can also stimulate imagination, aesthetic expression, and a sense of connection to the human joy and suffering,21, 33 and help people accept mystery and contradiction. 30, 34, 35, 36

Narrative Interventions

Unguided narratives may increase despair and hopelessness.21, 27 Instructor-led life review education combines individual and group activities to help people construct, revise and finalize their story and has reduced depression and improved agency in older adults. 37, 38, 39 While the benefits of deep writing are well acknowledged, 31, 40 it takes considerable skills, time and energy to participate in weekly classes and write a coherent life story. Integrative oncology clinicians use conversational techniques to elicit an illness narrative and explore salient themes,41, 42, 43 but this does not result in a manuscript.

Chochinov combined the oral aspects of integrative oncology with the written aspects of life review education. The clinician interviewed hospice patients to elicit a life story that focused on role identity, mastery, purpose, generativity, and life completion goals.44 The transcript was edited into a well-honed life manuscript, read to the patient, and revised. The patient was encouraged to share the final manuscript with loved ones. A non-randomized trial with 211 hospice patients found significant reductions in patient distress4 and bereaved survivors also benefited. The intervention is now being tested in a multi-national trial.45

Internet Use among Cancer Patients

Integrative oncology and life review programs are not widely offered and many patients cannot travel to available programs. Meanwhile, many patients use the Internet to gather information, communicate with peers and their social network, or post their story on their own websites.46 But many other patients do not have adequate access to the internet or the skills to create and post their stories. 47

Conclusion and Study Aims

Taken together, we hypothesized that using technology to synthesize Chochinov’s intervention, life review education, and eHealth could extend access and help patients earlier in the cancer trajectory. We received pilot funds from the University of Wisconsin Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Aging and Cancer program to (1) develop a prototype program and (2) test program components and research tools with 10 midlife to old age cancer patients, and (3) identify needed improvement and implications for further research.

Methods and Procedures

Intervention Components

The intervention included a telephone interview, life manuscript, and CHESS: miStory.

Telephone Interview

The interview questions, adapted from Chochinov44 to reflect the earlier phase in the cancer trajectory, included: Can you tell me about your life history (best times, growth, change, overcoming difficult times)? What are the most important things you have accomplished? What would you want your loved ones to remember about you? Is there anything you’d like to say to someone? What have you learned about life that you want to pass along to others? How has cancer affected you? (added) Is there anything else you’d like to share? An integrative medicine physician (LM) at the cancer center conducted interview by phone using active listening and relevant probes and prepared an interpretive summary of the patient’s experiences, strengths and motivations.

Manuscript

The PI (MW), an adult educator and qualitative researcher, edited the raw transcript to create a fluid story while maintaining the participant’s voice. For example, when a patient endorsed the observation, “It sounds like you were very close to your sister,” [“My sister and I were very close.”] was integrated into the narrative. The editor also inserted comments, such as [You may wish to expand on what it was like to have an AFS student live with you.] and prepared a summary document with observations and recommendations. The manuscript and interpretive summaries were delivered via paper and CHESS: miStory.

CHESS: miStory

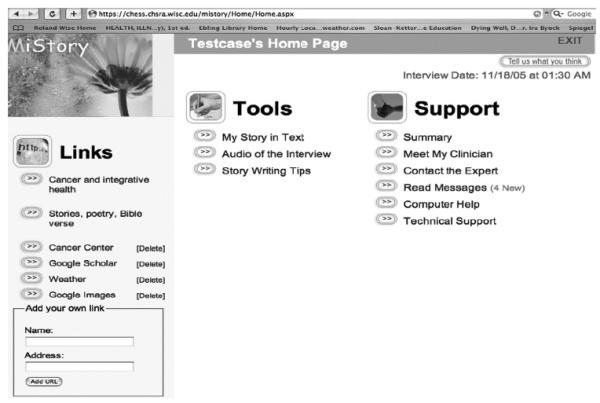

CHESS: miStory, was built on a reduced platform of the Comprehensive Health Enhancement System (CHESS) that has improved the well-being and healthcare participation in cancer patients. 48, 49, 50 As shown in Figure 1, Tools included “My Story in Text” and the editor’s notes in MS Word. Upon participants’ request, we added My Final Story and My Images. ”Story Writing Tips” provided suggestions for revising, adding images, and sharing the story. Links included websites for cancer, writing, life review, history, genealogy, and quotations. This section also provided tools for participants to add their own links. Support included the interviewer’s summary, internal expert email (MW), and technical support. A researcher toolbox (not shown) allowed for scheduling, uploading completed manuscripts and summaries, communication, and field notes. This model is described in Wise et al. 2007. 51

Figure 1.

CHESS: miStory personal homepage

Sample and Procedures

A convenience sample was recruited through a university-based comprehensive cancer center according to the IRB-approved protocol. Physicians invited patients ≥ age 40, who had completed primary chemotherapy treatment for any stage and type of cancer. The PI recruited by phone, explaining the study’s purpose and procedures, privacy protection and compensation. Upon return of signed IRB-approved informed consent forms, patients completed their telephone interview, received their life manuscript and home training on using CHESS: miStory, and the study Apple iBook laptop and scanner. The PI conducted all trainings and trained a student assistant in later implementations. At the end of the study, the PI retrieved study equipment, conducted an audiotaped exit interview, and downloaded revised documents and images. Participants received their files on CD and $20 compensation. Final story versions and images were uploaded and personal websites were left active.

Evaluation Tools

In-depth exit interviews were used to evaluate experiences with each intervention component. Questions asked about their experiences with each part of the study, how it affected them, and how they could be improved. Survey questions asked about ease of use and the helpfulness of each intervention component on a 5-point likert scale, but due to the small sample and missing data they did not inform the question. We also administered a long survey to inform measures for future studies, including the CES-D for depression and the post-traumatic growth inventory, 10 demographics, and a multi-dimensional measure of psychological well-being,52

Findings

Sample

Thirteen patients were invited to participate in the study and eleven enrolled. Both refusers objected to the website. One woman dropped due to a family problem that needed her undivided attention and one man was too sick to participate in the exit interview.

We recruited a diverse sample to identify which type of patient would use and benefit from the different intervention components.54 As shown in Table 1, the sample included four men and seven women (mean = 67, 43-85). All were Caucasian; six were >70, six had a high school degree and two had a post-graduate degree; six had an income of $40,000 or less. Six had Stage I and five had Stage IV cancer. Two Stage I patients had significant comorbidities and four (all >age 70) with no other health problems. Consistent with Pew research on Internet penetration,53 eight of the eleven participants had home Internet access. However, only two over age 65 could actually use them without support and even they required more staff and family support than their younger counterparts.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Gender | 4 Male | 7 Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(Mean 67) | 2 (< 55 years) | 3 (55-64 years) | 6 (> 70 years) |

| Cancer Stage | 6 (Stage I) | 0 (Stage II or III) | 5 (Stage IV) |

| Education | 6 (HS) | 3 (some college or BS) | 2 (post grad) |

| Home Internet | 8 (yes) | 3 (no) | |

| Computer Comfort | 5 (high) | 3 (some) | 3 (none) |

Three had baseline depression (>16, CES-D), but illness-related fatigue rather than sadness or hopelessness may have accounted for at least one case. Baseline scores for post-traumatic-growth, and psychological well-being were above the scales’ midpoints.

Participant Evaluation of the Study Components

We used dimensional analysis described by Strauss54 to analyze the exit interviews and the story manuscripts to identify how people used and evaluated the study components. There was too much missing survey data for meaningful quantitative analysis.

Telephone Interview to Elicit a Life Story

Everyone appreciated the opportunity to tell their story. Most people praised the interviewer’s skill and ease in encouraging their story. The original manuscripts indicate that people openly described their prior life challenges (poverty, divorce, widowhood, alcohol and drug addiction) and the important things they had learned, such as life is a gift, people are the most important priority, and “I am a better person due to cancer.” When asked, no one objected to having the interview by telephone and some preferred it. One woman fed her grandchild during the interview, noted, “Women have always multi-tasked while telling their stories.”

Receiving and Reflecting on the Manuscript

Everyone appreciated that their story had been captured, packaged and delivered. An accomplished professional (age 43) with metastatic breast cancer and debilitating medication effects said, “I could never have written this, but these are my words!”

A few people noted that telling and reading their story caused agitation and eventual resolution: “The question about what do I want to say to someone brought up the fact that I had never told my family I love them. It really bothered me. A few weeks later I told my sister and brother-in-law that I loved them and we all hugged. I am so glad I did this.” Another revealed that in the days after the interview, “I relived every bad thing I had ever done.” Several months later (after recovery from his metastatic cancer treatments) he was able to move on and reconnect with family and colleagues.

An 85 year-old man did not revise his original manuscript, because his once-high level skills were rusty. But at the exit interview he elaborated on his key manuscript themes, including how his parents’ love for each other and generosity had taught him to love. After describing how his whole family had contributed to their community theater, he concluded: “This has been so helpful. I always thought I had a pretty ordinary family, but it was really quite different.” When asked if he had shared the manuscript with is large, tight-knit family, he replied, “They can see it after I am gone.”

Revising the Story

Nine revised their original manuscript, four with minor computer revisions. Five overhauled their original story or produced significant addenda. One woman tripled the volume of her original story, including four original poems. Another left the original story in tact and wrote four vignettes, including a family tree, family health and cancer history, a day in the young family’s life, and hosting an AFS student (per the editor’s suggestion).

An 82-year-old expanded his story considerably and scanned 45 photographs (with considerable staff and family support). In an unsolicited email he wrote, “Now that this project is nearing completion, I am glad that I did it. It will be a wonderful record for my family and friends. Thank you for your help and patience.”

A 43 year-old with metastatic breast cancer borrowed a study scanner and noted, “This summer my 6-year old daughter and I will work on this together. I can’t focus on writing, but scanning photos and tweaking the text will be so fun for both of us.” She contacted us later to note that she was pasting story excerpts to create a slide show for her funeral.

One woman (age 70) noted that, “Reading [the original manuscript] made me more reflectiev.” and described the first draft as “just the shell and I want to get to the yolk.” But she refused to use the computer to further explore how a childhood of serious illness and a near death experience at age had affected her life purpose and choices. Instead she said, “I made several copies; cut [them] into strips and am writing by hand and pasting things together.”

CHESS: miStory

The communication tools and personal tools were most used and appreciated. One woman noted, “The expert feedback was valuable. I asked, ‘What should I do?’ You wrote, ‘Make it your own story.’ I took out the interview questions and began filling in details.” Web savvy users pushed us to expand the website capabilities so they could upload their own files and share them with their social network.

Living Story

Unexpectedly, the stories lived on. A widow shared, at length, how the story became part of the couple’s healing, forgiveness, peaceful death and bereavement. Another caregiver called to tell us about the story left by the bedside in its original envelope with a note that it be copied and distributed. This was from the man who had said,“They can see it after I go.”

Implementation Costs

It took two physician hours, four undergraduate hours, and three health-educator hours to elicit, transcribe and produce an edited story and expert summaries. We have since tested less costly strategies: A health educator can conduct the interviews and a trained and supervised undergraduate English or journalism major can do more extensive editing. A voice recognition program to automatically transcribe the interviews, was found too inaccurate. Finally, considerable staff time to train and support non-computer users resulted in participant frustrations flat rejection of using it for story revision. .

Discussion

A narrative intervention for cancer patients that combined Chochinov’s “dignity” interview and delivery of a life manuscript with a CHESS: miStory found that everyone benefited from telling and receiving their story, some people revised it, families were engaged in the process, and only people with prior computer experience used the web tools to revise or share the story.

Possible Mechanisms of Effect

Life Review Interview

“Jump starting” the story with an interview was valuable whether or not people went on to revise it. This is consistent with theories that humans are hardwired to make meaning of life through stories,55 and that constructing a story in conversation is easier than writing, as noted by one participant, “I could never have written this.” Polkinghorne and others suggest that storytelling and subsequent reflection allows for appraisal, clarifying values, and taking action.21, 22, 25, 26, 31, 30 This was illustrated by the woman who recognized her lack of emotional expression then was able say, “I love you” and by the man who reviewed “every bad thing I did” before he was able to move on.

Manuscript

Consistent with Chochinov’s findings, receiving the well-honed life manuscript may have been the most appreciated component of this intervention. Reading their fluid life story in their own words may have instilled a sense of pride in their life accomplishments, relationships and purpose in life.44, 45By contrast, wading through the raw transcript’s “ums,” tangents, repetitions and false start may have hampered these benefits.

Revising the story entailed self-reflection and generativity. Spending “time” with a long-deceased father was described as “self-therapy” illustrates how writing can deepen a sense of self and connectedness.56, 57 Cutting and rearranging the first draft on the dining room table, a process, similar to collage, stimulated creative pathways to move from the “egg shell….to the yolk” of exploring the impact of a near-death experience.58

Self and Others

Consistent with Chochinov, 4 families were woven into this patient-focused intervention.4 They were the most prominent story theme and helped with technology. Stories were regarded as a “record for my family and friends” and shared via paper or the website. They lived on with the bereaved.

Implications for Further Implementation and Research

This intervention seemed most beneficial and cost effective for computer-savvy people with high death salience. In this small sample, people with Stage IV cancer or life-threatening comorbidity had more complex and emotionally involved stories (e.g., vivid vignettes or poems to illustrate loss, falling in love or learning a lesson). By contrast, early stage patients with low threat used simpler life chronology constructions. While suffering has been associated with complexity and aesthetic expression, more research is needed in this arena.30, 33, 35

Computers and the Reflective Learning Process

Non-computer users (> 70) rejected using the computer to revise their story in contrast to prior studies where older patients learned to access CHESS information.48 We suspect that information retrieval is more passive than articulating thoughts about life and death and learning a computer may have hampered the reflective learning process. By contrast, computer savvy patients challenged CHESS to provide web 2.0 tools used for self-made websites, 13, 59 Future interventions, therefore, should focus on web-savvy advanced cancer patients.

Costs and Implementation Issues

While Chochinov suggests that life review is cost effective,4 the required staff time may pose a barrier for implementation within cancer centers. On the other hand, some hospices are training their skilled (and growing) volunteer corps to conduct life review.60

Training non-computer users was staff-intensive, frustrating for users who ultimately rejected the technology. Thus training novices is neither feasible nor cost-effective.

While we did enlist the advice of our clinical co-investigators, we were keenly aware their readiness to address patient distress was crucial given the depression, history of addiction, and difficult illness and other life challenges within our sample.

Next Steps

Midlife adults use self-publishing and social networking tools and cancer prevalence will increase among this age group,46, 61, 62, 63 We thus developed, CHESS: miLivingStory, on a social networking platform that integrates the instructional content of CHESS: miStory, with tools for users to upload their files and to manage their social network. We have proposed to test whether the revised intervention will reduce distress and improve existential well-being in midlife advanced cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a pilot grant from Aging and Cancer Program, University of Wisconsin Paul Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center, supported by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute for Aging (P20 CA103697-02, PI: Weindruch),and a pilot grant from the University of Wisconsin Center of Excellence and Cancer Communication Research (1P50CA095817-0181, PI :Gustafson), supported by the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

A limited version of this paper was presented at the Midwest Research-to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, September 26, 2007.

Commercial or financial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article: None

Contributor Information

Meg Wise, Associate Scientist Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies University of Wisconsin-Madison 1513 University Avenue, Room 4155-B Madison, WI 53706. mewise@wisc.edu.

Lucille Marchand, Professor Department of Family Medicine University of Wisconsin 770 Mills Street 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715, Madison WI 53726, Clinical Director of Integrative Oncology Services University of Wisconsin Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center; Director of Palliative Care Services, St. Mary’s Hospital, Madison, WI 53715, Lucille.marchand@fammed.wisc.edu..

James F. Cleary, Associate Professor of Hematology and Oncology, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin Clinical Sciences Center K4/546 Madison, WI 53792; jfcleary@wisc.edu.

Cited References

- 1.Byock I. The meaning and value of death. J Pall Med. 2002;5:279–288. doi: 10.1089/109662102753641278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block SD. Psychological issues in end-of-life care. J Pall Med. 2006;9:751–772. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker E. The denial of death. Free Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Onc. 2005;23(24):5520–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block SD. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end-of-life: the art of the possible. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2898–2905. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts LJ, Wise M, DuBenske L. Compassionate caregiving in the light and shadow of death. In: Fehr B, Sprecher S, Underwood L, editors. The Science of Compassionate Love: Research, Theory and Application. Blackwell Publishers; 2008. pp. 311–344. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kierkegaard SK. In: The sickness unto death. Translated. Lowrie W, editor. Doubleday; New York: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning. Hodder & Stoughton; London, England: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuebler-Ross E. On death and dying. Collier Books/Macmillan Publishing Co.; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter JS, Brockopp DY, Andrykowski MA. Self-transformation as a factor in the self-esteem and well-being of breast cancer survivors. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(6):1402–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordova M, Cunningham L, Carlson C, Andrykowski M. Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psych. 2001;20(3):176–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellizzi KM. Expressions of generativity and posttraumatic growth in adult cancer survivors. Intl J Aging Human Devel. 2004;58(4):267–288. doi: 10.2190/DC07-CPVW-4UVE-5GK0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yalom I. Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breitbart W, Heller K. [accessed, December 11, 2007];Reframing hope: meaning-centered care for patients near the end of life. Innov End-of-Life Care. 2002 4 http://www2.edc.org/lastacts/archives/archivesNov02/featureinn.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Classen C, Butler L, Koopman C, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Arch Gen Psych. 2001;58:494–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin PJ. Support groups in advanced breast cancer: Living better if not longer. Cancer. 2005;104(S11):2596–2601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiegel D, Classen C. Group Therapy for Cancer Patients. Basic Books; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, Gottheil Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2:888–891. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitbart W, Heller KS. Reframing hope: meaning-centered care for patients near the end of life. Innovations in End-of-Life Care. 2002;4(6) doi: 10.1089/109662103322654901. www.edc.org/lastacts [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank A. The Wounded Storyteller. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. Basic Books; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McQuellon RP, Cowan MA. Turning toward death together: conversations in mortal time. Am J Hospice Pall Care. 2000;17:312–318. doi: 10.1177/104990910001700508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeley MP. “Turning Toward Death Together”: The Functions of Messages during Final conversations in close relationships. J Soc Pers Rel. 2007;24:225–253. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polkinghorne DE. Transformative narratives: From passive to agentic life plots. American Jlf Occup Therapy. 1996;50(4):299–305. doi: 10.5014/ajot.50.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler R. The life review: an interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry. 1963;26:65–76. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler RN. Age, Death, and life review. Hospice Foundation of America; Apr 23, 2002. http://www.hospicefoundation.org/teleconference/2002/butler.asp. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erikson EM. Childhood and Society. 2nd Ed. W. W. Norton & Co.; New York: 1963. The eight stages of man; pp. 247–74. ch. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erikson EH, Erikson JM, Kivnick HQ. Vital Involvement in Old Age. W. W. Norton & Company; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ezzy D. Illness narratives: time, hope, and HIV. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(5):605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlick A, Biley FC. Thoughts on the therapeutic use of narrative in the promotion of coping with cancer. Eur J Can Care. 2004;13:308–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2004.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: the health benefits of narrative. Lit & Med. 2000;19(1):3–18. doi: 10.1353/lm.2000.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radley A. The aesthetics of illness: narrative, horror and the sublime. Sociol Health Ill. 1999;21(6):778–796. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labouvie-Vief G. Wisdom as integrated thought: Historical and developmental perspectives. In: Sternberg R, editor. Wisdom: It’s Nature, Origins, and Development. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 52–85. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plexus Institute . Stories: Complexity in action. Plexus Institute; Allentown, New Jersey: Apr 22, 2008. 08501. www.plexusinstitute.com. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreuter M, Green M, Cappella JN, Slater MD, Wise M, Storey D, Clark EM, O’Keefe DJ, Erwin DO, Holmes K, Hinyard LJ, Houston T, Wooley S. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(3):221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dominice P. Learning from Our Lives. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis MC. Life review therapy as an intervention to manage depression and enhance life satisfaction in individuals with right hemisphere cerebral vascular accidents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2004;25:503–515. doi: 10.1080/01612840490443455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mastel-Smith B, McFarlane J, Sierpina M, Malecha A, Haile B. Improving depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: a psychosocial intervention using life using life review and writing. J Geront Nurs. 2007:13–19. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1999;28:1304–1309. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro J, Ross V. Applications of narrative theory and therapy to the practice of family medicine. Fam Med. 2002;34(2):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchand L, Kushner K. Death pronouncements: surviving and thriving through stories. Fam Med. 2004;36(10):702–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charon R. Narrative and medicine. New Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):862–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care—a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;28(17):2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chochinov HM. Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects. CRISP; Dignity intervention for terminally ill cancer patients CRISP. 1R01CA102201-01A1. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fox S. Online health search 2006. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: [Accessed July 15, 2012]. Oct 29, 2006. 2006. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2006/Online-Health-Search-2006.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw B, Gustafson D, Hawkins R, McTavish F, McDowell H, Pingree S, Ballard D. How underserved breast cancer patients use and benefit from eHealth programs: implications for closing the digital divide. Am Behav Sci. 2006;49(6):823–834. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wise M, Gustafson DH, Sorkness C, Molfenter T, Meis T, Staresinic A, Shanovich KK, Walker NP. Internet telehealth for pediatric asthma case management: developing integrated computerized and case manager features for tailoring a web-based asthma education program. Health Prom Pract. 2007;8(3):282–291. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289983. DOI: 10.1177/1524839906289983. PMCID: PMC2366971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg EW, McTavish F, Owens B, Wise M, Berhe H, Pingree S. CHESS: ten years of research and development in consumer health informatics for populations, including the underserved. Intl J Med Informatics. 2002;65:169–177. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wise M, Han JY, Shaw B, McTavish M, Gustafson DH. The effects of narrative and didactic information on healthcare participation for breast cancer patients. Pat Educ Counsel. 2008;70(3):348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.009. [PMCID: PMC2367096] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wise M, Gustafson DH, Sorkness C, Molfenter T, Meis T, Staresinic A, Shanovich KK, Walker NP. Internet telehealth for pediatric asthma case management: developing integrated computerized and case manager features for tailoring a web-based asthma education program. Health Prom Pract. 2007;8(3):282–291. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289983. DOI: 10.1177/1524839906289983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryff C, Singer B. Psychological well being: Meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1996;65:14–23. doi: 10.1159/000289026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madden M. Internet Penetration and Impact 2006. Pew Internet & Am Life Project; [Accessed July 15, 2021]. 2006. 2006April 18, 2008. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2006/Internet-Penetration-and-Impact/Data-Memo.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strauss A. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bruner J. The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry. 1991;18:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charmaz K. In: Health, Illness and Healing: Society, Social Context, and Self. Charmaz K, Paterniti DA, editors. Roxbury Publishing Company; Los Angeles, CA: 1998. 1999. Ch 9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: the health benefits of narrative. Lit & Med. 2000;19:3–18. doi: 10.1353/lm.2000.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monti DA, Peterson C, Kunkel EJS, Hauck WW, Pequignot E, Rhodes L, Brainard JC. A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(5):363–373. doi: 10.1002/pon.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parker PA, Carl de Moor WF, Cohen Ll. Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(2):183–193. doi: 10.1002/pon.635. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergin M. [accessed April 22, 2008];New Projects Help Terminally Ill Patients Share Life Stories. The Capital Times. 2007 Oct 24; [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boase J, Horrigan JB, Wellman B, Rainie L. The Strength of Internet Ties. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: [Accessed April 18, 2008]. Jan, 2006. 2006. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2006/The-Strength-of-Internet-Ties.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Horrigan J. Home Broadband Adoption 2006. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: [Accessed July 15, 2012]. Apr 18, 2006. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2006/Home-Broadband-Adoption-2006.aspx. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madden M. Internet Penetration and Impact 2006. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: [Accessed July 15, 2021]. Apr 18, 2006. 2008. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2006/Internet-Penetration-and-Impact/Data-Memo.aspx. [Google Scholar]