Abstract

Objectives

Recent research has highlighted the phenotypic and genetic overlap of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder parallel those seen in schizophrenia, particularly for bipolar disorder patients with a history of psychotic features. Here we explored whether relational memory deficits, which are prominent in schizophrenia, are also present in patients with psychotic bipolar disorder.

Methods

We tested 25 patients with psychotic bipolar disorder on a relational memory paradigm previously employed to quantify deficits in schizophrenia. During the training, participants learned to associate a set of faces and background scenes. During the testing, participants viewed a single background overlaid by three trained faces and were asked to recall the matching face, which was either present (Match trials) or absent (Non-Match trials). Explicit recognition and eye-movement data were collected and compared to 28 schizophrenia patients and 27 healthy subjects from a previously published dataset.

Results

Contrary to our prediction, we found psychotic bipolar disorder patients were less impaired in relational memory than schizophrenia subjects. Bipolar disorder subjects showed eye-movement behavior similar to healthy controls, whereas schizophrenia subjects were impaired relative to both groups. However, bipolar disorder patients with current delusions and/or hallucinations were more impaired than bipolar disorder patients not currently experiencing these symptoms.

Conclusions

We found that patients with psychotic bipolar disorder had better relational memory performance than schizophrenia patients, indicating that a history of psychotic symptoms does not lead to a significant relational memory deficit.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia, associative memory, eye movements, hippocampus

According to Kraepelin, bipolar disorder is characterized as an episodic illness with recovery of function between acute mood episodes, whereas schizophrenia has a deteriorating course, resulting in more chronic and pervasive impairments (1). However, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia share several clinical features, including psychotic symptoms, which occur in at least 50 percent of bipolar disorder patients (2). Recent studies of cognition in patients with bipolar disorder also challenge the Kraepelinian dichotomy, providing evidence for a profile of stable cognitive deficits that persist during the euthymic state (3, 4), are present early in the course of illness (5) and predict functional outcomes (6–8). Most studies conclude that cognitive performance in bipolar disorder lies between schizophrenia and healthy controls (5, 9). Bipolar patients with a history of psychotic features exhibit greater domain-specific impairments than non-psychotic bipolar patients (8, 10, 11), and in some studies are indistinguishable from schizophrenia patients (12–14). The increasing evidence of shared genetic risk factors in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (15, 16), especially among patients with psychotic bipolar disorder (17), has led some researchers to suggest that bipolar disorder with psychotic features represents a separate subtype of the disorder (11).

While cognitive impairments are widespread in bipolar disorder, previous investigations have revealed particular deficits in verbal learning and memory (3, 4, 8, 10, 11), working memory (10), attention (18) and executive functions (4, 10). These cognitive abilities also discriminate between bipolar disorder patients with and without a history of psychosis, with psychotic bipolar patients exhibiting greater deficits in verbal declarative memory (8, 11), executive function (10, 11), and spatial working memory (10). Patients with schizophrenia are also impaired in these domains, further supporting an overlap between the disorders (19).

In the current study we tested how a history of psychotic symptoms impacts memory ability across diagnostic categories by comparing patients with psychotic bipolar disorder and patients with schizophrenia on a relational memory task. We recently used this paradigm (20) to quantify significant relational memory deficits in schizophrenia using both explicit recognition and eye-movement measures (21). Monitoring eye-movement behavior provides insight into early, automatic memory processes, and allows one to compare the time-course of memory retrieval between different groups or individual subjects (22). Our results were consistent with previous findings that patients with schizophrenia are more impaired on tests of relational memory, which require the binding together of multiple elements, than on tests of non-relational memory (23). At the neural level, relational memory deficits have been linked to structural, functional, and biochemical abnormalities of the hippocampus in schizophrenia (24, 25). Crucially, previous studies with this eye-tracking paradigm indicate that early, memory related eye-movements are also supported by the hippocampus (20, 26). Since a growing number of studies has revealed a pathology of hippocampal neurons in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder (27, 28), we hypothesized that similar relational memory deficits may also be present. However, this strong hypothesis was tempered by the inconclusive evidence regarding hippocampal volume change (27, 29) and relational memory deficits (30–33) in bipolar disorder.

Materials and methods

Participants

We studied 31 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, type I with psychotic features, and selected demographically similar samples of 27 healthy controls and 28 patients with schizophrenia from our previously published dataset (21). All participants completed written informed consent after approval of the study protocol by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (Nashville, TN, USA). Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were recruited from both the inpatient unit of the Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital and outpatient providers; healthy controls were recruited from the community via posted advertisements. All participants completed a detailed interview that included the Structured Clinical Interview of the DSM-IV (SCID) (34) and the National Adult Reading Test (NART) (35) as a measure of pre-morbid IQ. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder subjects were also given the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (36), the Young Mania Rating Scale (37), and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (38). The psychiatric diagnoses were finalized in a diagnostic consensus conference, utilizing information from the SCID and medical record. Individuals with a history of head injury, seizures, a serious medical condition (e.g., HIV, cancer), loss of consciousness, or drug dependence were excluded. Healthy control participants were excluded if they had a history of mental illness, had ever been prescribed psychotropic medication, or had a first degree relative with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. Only participants who reported normal or corrected-to-normal eyesight and intact color vision were included. After task administration, six bipolar disorder subjects were excluded due to technical problems during data collection.

Our final study group (Table 1) included 27 healthy controls, 25 patients diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, severe, with psychotic features, and 28 patients diagnosed with either schizophrenia (n = 18) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 10). Patients in the bipolar disorder group were included into the study regardless of current mood state: depressed (n = 9), manic (n = 1), mixed (n = 3), or euthymic (n = 12). Mood states were determined using previously published cut-offs of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [depressed state: score ≥ 8 (39)] and the Young Mania Rating Scale [manic state: score ≥ 13 (37)], with a mixed state defined by scores meeting criteria for both depression and mania. Within the bipolar disorder sample eight subjects reported only experiencing delusions when they became psychotic, one reported only experiencing hallucinations and 16 reported experiencing both. Comparison groups of schizophrenia patients and healthy control subjects were selected from our previously published data set (21), based on demographic characteristics (race, gender, age, handedness, parental and subject education, pre-morbid IQ) and clinical symptoms for the schizophrenia group (degree of depression, mania, and psychotic symptoms at the time of study). The schizophrenia and bipolar disorder groups were statistically similar on all clinical and demographic variables, with the exception of higher scores for schizophrenia patients on the PANSS Negative, PANSS General, and total PANSS scores (Table 1). Schizophrenia patients also reported significantly more inpatient hospitalizations than bipolar disorder patients but groups did not differ on duration of illness. The healthy control sample did not differ from the bipolar disorder and schizophrenia groups on any demographic variables, except for years of education (control > schizophrenia, control > bipolar) and pre-morbid IQ (control > schizophrenia). For the subjects taking antipsychotics (28 schizophrenia, 16 bipolar disorder subjects), chlorpromazine equivalent doses were calculated according to Gardner (40). Within the bipolar disorder sample 14 individuals were taking one mood stabilizer, 2 individuals were taking 2 mood stabilizers, 4 individuals were taking an antidepressant, and 5 individuals were taking an anti-anxiety medication.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participantsa

| Bipolar disorder with psychotic features (n = 25) | Schizophrenia (n = 28) | Healthy controls (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female), n | 8/17 | 13/15 | 13/14 |

| Race (African American/White/Other), n | 3/20/2 | 9/18/1 | 5/20/2 |

| Age, years | 35.0 (12.47) | 39.1 (11.76) | 35.0 (11.00) |

| Education, yearsb,c | 13.9 (2.84) | 13.2 (2.53) | 15.2 (1.60) |

| Parental education, years | 14.5 (4.34) | 12.6 (3.45) | 12.9 (2.87) |

| IQ, NARTc | 109.5 (8.44) | 106.4 (9.30) | 111.6 (6.06) |

| Handedness (R/L/ambidextrous) | 23/0/2 | 18/2/6 | 21/1/3 |

| HAM-D score | 9.9 (9.39) | 8.0 (7.43) | – |

| YMRS score | 5.4 (7.70) | 3.1 (3.53) | – |

| PANSS–Total scored | 46.9 (7.94) | 57.2 (14.72) | – |

| PANSS–Positive score | 12.6 (4.34) | 14.7 (5.33) | – |

| PANSS–Negative scored | 10.0 (3.19) | 15.1 (4.97) | – |

| PANSS–General scored | 23.9 (5.46) | 27.4 (7.60) | – |

| CPZ | 450.7 (266.79) | 416.8 (233.34) | – |

| Duration of illness, years | 15.3 (11.44) | 17.2 (10.24) | – |

| No. of hospitalizationsd | 3.1 (2.76) | 8.0 (7.71) | – |

NART = North American Adult Reading Test; R = right; L = left; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CPZ = chlorpromazine equivalent doses.

Mean standard deviation (SD) unless indicated otherwise.

Significantly different between bipolar disorder and healthy control groups at p < 0.05.

Significantly different between schizophrenia and healthy control groups at p < 0.05.

Significantly different between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia groups at p < 0.05.

Align values by left parenthesis.

While many studies combine patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder into a larger ‘schizophrenia’ group, differential diagnosis between schizoaffective disorder and psychotic bipolar disorder can be challenging due to phenotypic overlap. In the current sample there was a clear difference in clinical profile between patients with schizoaffective disorder and the psychotic bipolar disorder group, such that patients with schizoaffective disorder had higher PANSS Negative, General and Total scores and a greater number of hospitalizations than psychotic bipolar disorder patients (all t’s > 2.22, all p’s < 0.033). Additionally, scores on the clinical scales did not differ between patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, with the exception of higher mania scores for schizoaffective patients [t(26) = 2.79, p = 0.01].

Experimental paradigm

The experimental task has been described previously (21). Bipolar disorder subjects were tested with the same stimuli as schizophrenia and control subjects and their eye-movements were collected on an Applied Science Laboratories (ASL) model D6 remote eye-tracker. The relational memory task included a training phase immediately followed by a testing phase. During training, participants viewed 36 background scene-face pairs, and were instructed to try and remember which face was paired with each background. On each training trial a unique, real-world background scene was presented alone for 3 seconds, and overlaid by a face for 5 seconds (Fig. 1). Participants viewed 3 blocks of 36 face-scene pairs presented in a randomized order. Test trials began with a 3 second display of a previously trained background, followed by 10 seconds during which three previously seen faces were superimposed on the background in the upper left, upper right, and bottom portions of the screen. There were 12 test trials, 6 of which were Match trials in which one of the three faces had been previously paired with the background, and 6 were Non-Match trials in which none of the three faces had been previously paired with the background. Participants were instructed to try and remember which face had been paired with the background during training, without giving an explicit response, and to keep their eyes on the screen the entire time even if no matching face was present. All faces were equally familiar from the training phase, and on Match trials, the matching face was seen equally often in the upper left, upper right, and bottom position. Lists of stimuli were rotated and counterbalanced across participants to ensure balanced pairings of faces and scenes across the study.

Fig. 1.

Experimental paradigm. During the training, participants viewed three randomized blocks of 36 face-background scene pairs. During the testing, participants viewed 12 test displays in which a background scene was overlaid by three previously learned faces. In half of the test trials, the face paired with the background scene during training was included as one of the three faces (Match); the other half of test trials did not include the previously learned face (Non-Match). Test trials began with a three second presentation of the background scene in isolation. Reproduced with permission from Williams et al., Biological Psychiatry, 2010 (21).

Eye-movement behavior

Eye movements were collected during all three training blocks and the test block. Eye movements during the test trials were categorized by viewing of each display element: Face Upper Left, Face Upper Right, Face Bottom, and Background. Viewing measures included: (i) the duration of fixations on each display element and (ii) time-course measures of the proportion of time spent looking at each display element across the 10-sec trial.

Explicit memory testing

Explicit recognition of the face-scene pairings was assessed using a four-alternative forced choice memory test immediately following the eye-movement test block for the majority of participants (bipolar disorder n = 25, healthy control n = 22, schizophrenia n = 25). Participants again viewed the 12 test trials and used either a keyboard or button box to indicate the matching face, or to indicate that no matching face was present.

Statistical analysis of behavioral and eye-movement data

Group differences in eye-movement behavior were analyzed with two statistical approaches: (i) one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for proportion of viewing of the matching face within Match trials and (ii) repeated-measures ANOVA that examined viewing patterns by face type (Match, Non-Match), and face position (upper left, upper right, or bottom) across diagnostic groups. The time-course data were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA on the first 2000 msec of each Match test trial to test for group differences in the onset of preferential viewing of the matching face. Explicit recognition was compared between groups using a one-way ANOVA and planned, two-tailed independent samples t-tests. All unplanned post-hoc tests and the time-course repeated measures ANOVA were Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Eye-movement behavior

Participants spent the majority of each 10 second test trial looking at the screen (Match trials: control subjects = 9.0 ± 0.4 sec, bipolar disorder subjects = 8.6 ± 0.6 sec, schizophrenia subjects = 8.7 ± 0.7 sec; Non-Match trials: control subjects = 8.6 ± 0.7 sec, bipolar disorder subjects = 8.0 ± 0.9 sec, schizophrenia subjects = 8.5 ± 0.6 sec) with minimal time spent on blinks or transitions.

The Match trials allowed for a comparison of viewing patterns between the three groups when a relational memory trace was present. Average proportion of viewing of the matching face was compared across groups, with longer viewing interpreted as more robust relational memory retrieval consistent with previous studies (20). The three groups differed significantly in the proportion of time spent looking at the matching face [main effect of group, F(2,77) = 19.66, p < 0.001]. Planned independent sample t-tests showed that healthy controls and bipolar disorder subjects had similar viewing of the matching face [t(50) = 1.55, p = 0.128; Cohen’s d = 0.43], however schizophrenia subjects spent significantly less time viewing the matching face than both bipolar disorder subjects [t(51) = 4.07, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.11] and healthy controls [t(53) = 6.8, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.83] (Fig. 2). Viewing of the matching face did not differ between patients with schizophrenia and patients with schizoaffective disorder [t(26)=0.51, p = 0.617], and patients with psychotic bipolar disorder had greater match face viewing than patients with schizoaffective disorder [t(33) = 3.20, p < 0.01].

Fig. 2.

Average [± standard error (SE)] proportion of time spent viewing the matching face during Match trials (Black) and the non-matching faces during Non-Match trials (Gray), collapsed across face position. During Non-Match trials, all groups showed equivalent viewing of the non-matching faces. During Match trials, when a relational memory trace was present, bipolar disorder and control subjects exhibited similar preferential viewing of the matching face for the majority of the test trial, in contrast to schizophrenia patients who had significantly reduced preferential viewing of the matching face relative to both bipolar disorder and control participants.

A 2 (Face type: Match, Non-match in Non-match condition) by 3 (Face position: upper left, upper right, bottom) by 3 (Group: control, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess group differences in viewing patterns between Match and Non-Match test trials. The proportion of time spent viewing each face location during the Non-Match trials represents the baseline viewing pattern for each group, and an interaction between face type and group indicates a differential effect of relational memory on viewing patterns. We found a main effect of group [F(2,76) = 66.96, p < 0.001; control > bipolar disorder> schizophrenia for overall viewing] and a main effect of face type [F(2,76) = 200.51, p < 0.001, Match viewing > Non-Match viewing]. Crucially, there was a significant face type by group interaction [F(2,76) = 54.41, p < 0.001], indicating that the magnitude of preferential viewing of the matching face differed between groups. Follow up ANOVAs showed no face type by group interaction between bipolar disorder subjects and healthy controls [F(1,49) = 1.32, p = 0.256], indicating these groups showed similar preferential viewing of the Match face, relative to Non-Match face viewing. However, there was a significant face type by group interaction between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder subjects [F(1,50) = 69.94, p < 0.001] and schizophrenia and control subjects [F(1,53) = 161.71, p < 0.001], such that the bipolar disorder and control groups both spent more time viewing the Match faces, relative to Non-Match faces, whereas patients with schizophrenia had more equivalent viewing of Match and Non-Match faces (Fig. 2). The pattern of results was unchanged when only explicitly correct trials were analyzed, indicating that differences in explicit recognition were not driving between-group differences.

Time-course analysis of proportional viewing time

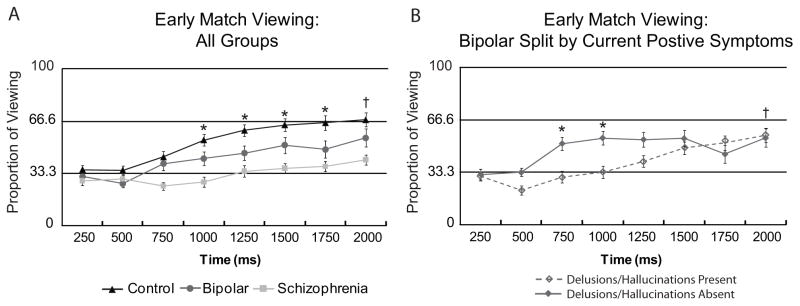

To quantify group differences in onset of preferential viewing of the matching face, proportion of match-face viewing was compared across groups within 250 msec time bins. The onset of preferential match-face viewing was defined as greater than chance (e.g., 33.33 percent) viewing for two consecutive 250 msec time-bins within the first two seconds of test display presentation. This bin size and time duration were chosen based on previous studies using this paradigm that demonstrated this organization is sufficient to capture the rapid onset of preferential viewing of the matching face (20, 26). A series of one sample t-tests showed that healthy control subjects begin to preferentially view the matching face at 1000 msec [t(26) = 5.63, p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected](Fig. 3A) and maintain this preferential viewing throughout the rest of the trial (Fig. 4). Bipolar disorder subjects have a delayed preferential viewing onset compared with controls, beginning consistent preferential viewing of the matching face at 2000 msec [t(24) = 3.87, p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected](Fig. 3A), which continues for the rest of the test display (Fig. 4). In contrast, patients with schizophrenia do not show early preferential viewing of the matching face (Fig. 3A). Schizophrenia subjects view the matching face significantly above chance between 4 and 6 seconds of the test display, but this pattern does not persist throughout the display and is less robust than that of healthy controls and bipolar disorder subjects (Fig. 4). Group differences in the onset of preferential viewing were confirmed with a 3 (group: control, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) by 8 (time bin: from 0–2000 msec in 250 msec increments) repeated-measures ANOVA, which revealed a main effect of group [F(2,77) = 18.39, p < 0.001], a main effect of time [F(2,71) = 11.13, p < 0.001], and a group by time interaction [F(2,144) = 2.11, p < 0.05]. Follow up ANOVAs showed a main effect of group for healthy control and bipolar disorder subjects [F(50) = 7.93, p < 0.01] but no group by time interaction [F(1,44) = 1.24, p = 0.30], indicating a similar time-course of early match viewing. In contrast, there was a significant time by group interaction between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia subjects [F(1,45) = 3.75, p < 0.01]. A similar pattern was found for an analysis of explicitly correct trials only.

Fig. 3.

Average [± standard error (SE)] proportional viewing of the matching face over time for the first 2000 msec of test display for (A) all groups and (B) the bipolar disorder group split by presence of current delusions/hallucinations at time of test. In panel A starred values (*) indicate greater than chance (0.33) viewing of the matching face for an individual time bin, p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected for healthy controls, and values marked with a cross (†) indicate preferential viewing for both healthy controls and bipolar disorder subjects. For healthy controls preferential viewing emerges within 1000 msec of display presentation whereas bipolar disorder patients show a slightly delayed pattern, with emergence of preferential viewing at 2000 msec. In contrast, schizophrenia patients fail to show preferential match-face viewing during the early display period. In panel B bipolar disorder subjects without current delusions/hallucinations display an early spike in preferential viewing of the matching face that is not present in bipolar disorder subjects with current delusions/hallucinations, resulting in a significant group by time interaction [F(17) = 4.58, p < 0.01]. Preferential viewing for bipolar disorder subjects without current delusions/hallucinations is indicated by starred values, with a cross representing the time point at which both bipolar disorder groups show preferential viewing.

Fig. 4.

Average [± standard error (SE)] proportional viewing of the matching face over the entire 10-sec test trial in 250 msec timebins. Both control and bipolar disorder participants consistently view the matching face above chance (33.3) for the majority of the test display, with proportion of viewing above 60% after the first two seconds. In contrast, schizophrenia patients do not exhibit robust preferential viewing of the matching face, never exceeding 50% for an individual timebin.

Explicit recognition

Explicit responses were recorded during a separate test block directly following the collection of eye-movement data for most subjects (22 control, 25 schizophrenia and 25 bipolar disorder subjects). Control subjects had more accurate explicit recognition than both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia subjects on Match trials [mean and standard deviation (SD): control 95 ± 9%, bipolar disorder 77 ± 25%, schizophrenia 54 ± 27%; F(2,69) = 18.2, p < 0.001], Non-Match trials [control 74 ± 29%, bipolar disorder 39 ± 40%, schizophrenia 25 ± 29%; F(2,69) = 13.5, p < 0.001], and testing overall [control 84 ± 15%, bipolar disorder 59 ± 28%, schizophrenia 40 ± 25%; F(2,69) = 20.8, p < 0.001]. Bipolar disorder subjects had significantly higher accuracy on Match trials [t(48) = 3.0, p < 0.01] and testing overall [t(48) = 2.5, p < 0.05] when compared with schizophrenia subjects, however their accuracy did not differ during Non-Match trials. The main effect of group remained significant when years of subject education was included as a covariate, with bipolar disorder participants showing worse explicit performance than controls across conditions [Match F(2,44) = 8.48, p = 0.001; Non-Match F(2,44) = 6.0, p < 0.01; testing overall F(2,44) = 9.49, p < 0.001]. Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder patients did not differ in explicit performance [Match t(23) = 0.05, p = 0.962; Non-Match t(23) = 0.169, p = 0.867; testing overall t(23) = 0.162, p = 0.872]. Similarly, comparisons between psychotic bipolar disorder and schizoaffective patients yielded a similar pattern to the bipolar versus schizophrenia group [Match t(32) = 2.27, p = 0.03; Non-Match, t(32) = 0.86, p = 0.40; testing overall t(32) = 1.7, p = 0.099].

Exploratory subgroup analyses within the bipolar disorder group

We compared memory performance between groups of bipolar disorder subjects defined by their mood state and degree of psychosis at the time of study. Memory performance did not significantly differ between bipolar disorder patients who were currently euthymic [n = 12; mean and (SD) for proportion of viewing of the Match face: 0.74 (0.18)], depressed [n = 9; 0.58 (0.26)], or mixed/manic [n = 4; 0.81 (0.12)], though there was a trend for worse performance in the depressed group [overall Match viewing: main effect of group F(24) = 2.27, p = 0.13; partial η2= 0.153]. We also compared performance between bipolar disorder patients experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of study (a score of 3 or above on the delusions and/or hallucinations subscale on the PANSS; n = 14) and those who were not (n = 11). These subgroups did not differ on any clinical or demographic variable listed in Table 1 with the exception of parental education [not psychotic > psychotic, t(22) = 2.06, p = 0.05], PANSS Positive score and PANSS Total score. Bipolar disorder subjects who were experiencing delusions and/or hallucinations showed significantly reduced Match viewing [t(39) = 2.54, p < 0.05] and reduced explicit Match accuracy [t(33) = 3.97, p < 0.001] relative to healthy controls, whereas bipolar disorder patients without current positive symptoms did not [Match viewing: t(36) = 0.024, p = 0.98; explicit Match accuracy: t(30) = 1.61, p = 0.12]. However, the subgroup of bipolar disorder patients with current positive symptoms still had better performance compared to patients with schizophrenia [Match viewing: t(40) = 2.55, p < 0.05; explicit Match accuracy: t(37) = 1.8, p = 0.08]. The early time course data reveal an early spike of preferential match viewing in the non-symptomatic group that is not present in the bipolar disorder patients with current positive symptoms (significant interaction between group (current positive symptoms, no current positive symptoms) and time [F(17) = 4.58, p < 0.01](Fig. 3B). In contrast, splitting bipolar disorder patients by number of hospitalizations did not yield any differences in memory performance: Match proportion of viewing: [t(23) = 0.91, p = 0.38]; explicit Match accuracy: [t(23) = 0.36, p = 0.72].

Predictors of relational memory performance

Demographic and clinical data were assessed for their ability to predict relational memory performance during test trials. For healthy controls, parental education was a significant predictor of explicit recognition on Match trials (r = 0.46, p < 0.05), but no other variables were correlated with memory performance. Within the bipolar and schizophrenia groups, explicit memory performance was predicted by subject education, parental education and pre-morbid IQ (all r’s > 0.42, all p’s < 0.05), but memory performance was not related to scores on any clinical scale or medication dosage. Preferential viewing of the matching face was not predicted by any demographic or clinical variable with the exception of age for the bipolar disorder group (r = 0.59, p < 0.01).

Discussion

In contrast to our hypothesis, these data provide evidence that patients with bipolar disorder and a history of psychotic symptoms are less impaired in relational memory than a demographically and clinically similar sample of patients with schizophrenia. Although patients with bipolar disorder showed slightly reduced performance relative to healthy controls, these differences reached statistical significance only for explicit recognition and the magnitude of early match viewing, but not for any other eye-movement memory measure.

Control participants showed greater than chance preferential viewing of the matching face nearly a second earlier than bipolar disorder patients (1000 msec for controls, 2000 msec for bipolar disorder patients), which also lead to greater match viewing for control participants during this early period. This suggests a delayed onset but otherwise intact relational memory in bipolar disorder subjects, as evidenced by their continued viewing of the Matching face throughout the remainder of the test trial. In contrast, early preferential viewing of the matching face is completely absent for schizophrenia subjects, and their viewing of the matching face is much reduced throughout the entire trial relative to both controls and patients with bipolar disorder. On explicit relational memory recognition, patients with psychotic bipolar disorder showed an intermediate deficit between healthy controls and patients with schizophrenia, a pattern similar to other studies of cognitive abilities in bipolar disorder patients (5, 9). These findings suggest that the experience of psychosis alone does not lead to the relational memory deficits seen in schizophrenia. While further research is needed to fully understand the cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder, these data are consistent with better cognitive performance in bipolar disorder than in patients with schizophrenia.

Impairments in relational memory encoding and hippocampal recruitment have been extensively explored in schizophrenia (23, 24), but are less well understood in bipolar disorder, particularly in psychotic bipolar disorder. Two behavioral studies have investigated paired associate learning in patients with bipolar disorder, one finding impaired performance in bipolar disorder patients (33), and one finding similar performance to healthy control subjects (32). Unfortunately, neither of these studies reported whether bipolar disorder patients had a history of psychosis, so it is unknown if that factor could explain the discrepant findings. Two recent fMRI studies have employed a face-name paired associate task, and compared the neural networks that support relational encoding and retrieval between patients with bipolar disorder and healthy controls in the context of matched behavioral performance. Glahn et al. (30) found that a sample of bipolar disorder participants without a history of psychosis exhibited normal hippocampal activity during relational encoding, but failed to activate hippocampal regions to the same extent as controls during recognition. In contrast, Hall et al (31) compared a sample of patients with bipolar disorder, many of whom had a history of psychotic features, to both healthy controls and schizophrenia patients, finding that patients with bipolar disorder did not show differential activation of the hippocampus compared to controls, while schizophrenia patients exhibited abnormal hippocampal activity. As both explicit relational memory (41), and the early eye-movement effects detailed in this study are thought to be related to hippocampal integrity (20, 26), we propose that our results are consistent with a mild hippocampal deficit in patients with psychotic bipolar disorder, evidenced by an intermediate deficit in explicit relational memory performance, and a slight delay in the onset of preferential viewing relative to healthy controls.

Hippocampal dysfunction has been proposed as a possible neural substrate of psychotic symptoms, in particular delusions and hallucinations (for review see 24). Therefore, as an exploratory analysis we split our group of bipolar disorder subjects into those who were and were not experiencing delusions and hallucinations at the time of study, finding more severe relational memory impairments in patients with current delusions and/or hallucinations. While this group difference suggests that active positive symptoms may influence hippocampal-dependent memory performance, future studies with a larger sample size, more patients with current manic symptoms, and additional experimental controls are needed to validate this pattern.

Strengths of the current study include demographically and clinically similar samples of patients with schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder, the use of a task that specifically tests relational memory, and the inclusion of both explicit and eye movement outcome measures. The monitoring of early eye movements provides a rapid, non-verbal measure of memory recognition in isolation from response selection and response execution (22). In addition, whereas explicit recognition is correlated with education and pre-morbid IQ scores across groups, preferential viewing is only related to age in the bipolar disorder sample.

One limitation of the current study is the use of psychotropic medications by the majority of the patients. Studies on the impact of psychotropic medications on cognitive performance have been largely inconclusive, although there is some evidence to suggest that both lithium (42) and atypical antipsychotics (43) may improve cognitive functions such as memory and attention. In our sample, lithium dose and chlorpromazine equivalent doses did not correlate with performance and both patient groups were treated with similar CPZ equivalent dosages, but had different memory performance. This indicates that the between-group differences are not simple medication effects. All three subject groups had relatively high premorbid IQ scores, which may limit the generalizability of these findings to the broader population of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. However, the absence of a correlation between eye-movement behavior and premorbid IQ in any group indicates similar patterns may be found in participants with lower intellectual function. The experimental task includes only a small number of test trials (six Match, six Non-Match), though this is comparable to other studies on relational memory in schizophrenia (44). Finally, while the two clinical samples did not differ in age and duration of illness, most were chronic. Therefore, further studies should explore relational memory deficits in the early stages of psychosis.

This study is the first to investigate relational memory ability in a sample of patients with bipolar disorder and a history of psychotic features, using both explicit recognition and indirect eye movement measures. Contrary to our hypothesis, relational memory was not similarly impaired in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder patients. These findings support the notion that hippocampal-dependent memory is more affected in schizophrenia than in affective psychosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant No. RO1-MH070560 (SH).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors of this paper do not have any commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kraepelin E. Manic-Depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frederick K, Goodwin KRJ. Manic-Depressive Illness. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurtz MM, Gerraty RT. A meta-analytic investigation of neurocognitive deficits in bipolar illness: profile and effects of clinical state. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:551–62. doi: 10.1037/a0016277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Goswami U, Young AH, Ferrier IN, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;93:105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichenberg A, Harvey PD, Bowie CR, Mojtabai R, Rabinowitz J, Heaton RK, et al. Neuropsychological function and dysfunction in schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:1022–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bearden CE, Woogen M, Glahn DC. Neurocognitive and neuroimaging predictors of clinical outcome in bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:499–504. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, et al. Prediction of real-world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1116–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Arán A, Vieta E, Colom F, et al. Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients: implications for clinical and functional outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krabbendam L, Arts B, van Os J, Aleman A. Cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:137–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Barguil M, Barrett J, Reichenberg A, Bowden CL, et al. The neurocognitive signature of psychotic bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:910–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Salamero M, Daban C, Balanza-Martinez V, et al. Neurocognitive impairment in bipolar patients with and without history of psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:233–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill SK, Reilly JL, Harris MS, Rosen C, Marvin RW, Deleon O, et al. A comparison of neuropsychological dysfunction in first-episode psychosis patients with unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simonsen C, Sundet K, Vaskinn A, Birkenaes AB, Engh JA, Faerden A, et al. Neurocognitive dysfunction in bipolar and schizophrenia spectrum disorders depends on history of psychosis rather than diagnostic group. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:73–83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and affective psychoses: meta-analytic study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:475–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craddock N, Owen MJ. The beginning of the end for the Kraepelinian dichotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:364–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray RM, Sham P, Van Os J, Zanelli J, Cannon M, McDonald C. A developmental model for similarities and dissimilarities between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2004;71:405–16. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potash JB, Willour VL, Chiu YF, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, Pearlson GD, et al. The familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder pedigrees. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1258–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bearden CE, Hoffman KM, Cannon TD. The neuropsychology and neuroanatomy of bipolar affective disorder: a critical review. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:106–150. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barch DM. The cognitive neuroscience of schizophrenia. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2005;1:321–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannula DE, Ryan JD, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. Rapid onset relational memory effects are evident in eye movement behavior, but not in hippocampal amnesia. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2007;19:1690–705. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.10.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams LE, Must A, Avery S, Woolard A, Woodward ND, Cohen NJ, et al. Eye Movement Behavior Reveals Relational Memory Impairment in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:617–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannula DE, Althoff RR, Warren DE, Riggs L, Cohen NJ, Ryan JD. Worth a glance: using eye movements to investigate the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4:166. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achim AM, Lepage M. Is associative recognition more impaired than item recognition memory in Schizophrenia? A meta-analysis. Brain and cognition. 2003;53:121–4. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heckers S, Konradi C. Hippocampal pathology in schizophrenia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:529–53. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lisman JE, Coyle JT, Green RW, Javitt DC, Benes FM, Heckers S, et al. Circuit-based framework for understanding neurotransmitter and risk gene interactions in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:234–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannula DE, Ranganath C. The eyes have it: hippocampal activity predicts expression of memory in eye movements. Neuron. 2009;63:592–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frey BN, Andreazza AC, Nery FG, Martins MR, Quevedo J, Soares JC, et al. The role of hippocampus in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:419–30. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282df3cde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konradi C, Zimmerman EI, Yang CK, Lohmann KM, Gresch P, Pantazopoulos H, et al. Hippocampal interneurons in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:340–50. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald C, Zanelli J, Rabe-Hesketh S, Ellison-Wright I, Sham P, Kalidindi S, et al. Meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging brain morphometry studies in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glahn DC, Robinson JL, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Monkul ES, Holmes MK, Green MJ, et al. Fronto-temporal dysregulation in asymptomatic bipolar I patients: a paired associate functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:1041–51. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall J, Whalley HC, Marwick K, McKirdy J, Sussmann J, Romaniuk L, et al. Hippocampal function in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2010;40:761–70. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Killgore WD, Rosso IM, Gruber SA, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Amygdala volume and verbal memory performance in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2009;22:28–37. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e318192cc67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Hughes JH, Watson S, Gray JM, Ferrier IN, et al. Neurocognitive impairment in euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:32–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson HE. National Adult Reading Test (NART): Test Manual. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 1978;133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furukawa TA, Akechi T, Azuma H, Okuyama T, Higuchi T. Evidence-based guidelines for interpretation of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:531–4. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31814f30b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:686–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ongur D, Cullen TJ, Wolf DH, Rohan M, Barreira P, Zalesak M, et al. The neural basis of relational memory deficits in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:356–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yucel K, McKinnon MC, Taylor VH, Macdonald K, Alda M, Young LT, et al. Bilateral hippocampal volume increases after long-term lithium treatment in patients with bipolar disorder: a longitudinal MRI study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;195:357–67. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meltzer HY, McGurk SR. The effects of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:233–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ongur D, Cullen TJ, Wolf DH, Rohan M, Barreira P, Zalesak M, et al. The neural basis of relational memory deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:356–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]