Abstract

Lifestyle interventions have resulted in weight loss or improved physical fitness among individuals with obesity, which may lead to improved physical function. This prospective investigation involved participants in the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial who reported knee pain at baseline (n = 2,203). The purposes of this investigation were to determine whether an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) condition resulted in improvement in self-reported physical function from baseline to 12 months vs. a Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) condition, and whether changes in weight or fitness mediated the effect of the ILI. Outcome measures included the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain, stiffness, and physical function subscales, and WOMAC summary score. ILI participants exhibited greater adjusted mean weight loss (s.e.) vs. DSE participants (−9.02 kg (0.48) vs. −0.78 kg (0.49); P < 0.001)). ILI participants also demonstrated more favorable change in WOMAC summary scores vs. DSE participants (β (s.e.) = −1.81 (0.63); P = 0.004). Multiple regression mediation analyses revealed that weight loss was a mediator of the effect of the ILI intervention on change in WOMAC pain, function, and summary scores (P < 0.001). In separate analyses, increased fitness also mediated the effect of the ILI intervention upon WOMAC summary score (P < 0.001). The ILI condition resulted in significant improvement in physical function among overweight and obese adults with diabetes and knee pain. The ILI condition also resulted in significant weight loss and improved fitness, which are possible mechanisms through which the ILI condition improved physical function.

Introduction

Overweight (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) currently affect over 65% of US adults (1), and their prevalence is expected to increase over the next decade. Obesity is associated with a number of comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes (2–4) and knee pain (5). The etiology of knee pain is multifactorial, and can range from chronic diseases such as osteoarthritis (OA) (6) to acute trauma (7). Nonetheless, obesity has been identified as an independent, yet modifiable risk factor for the development and treatment of knee pain (8).

Several studies, including the Observational Arthritis Study in Seniors (OASIS), the Fitness Arthritis in Seniors Trial (FAST), and the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial (ADAPT) have demonstrated that physical activity has a positive effect on pain, physical function (9,10), and health-related quality of life (11) among overweight and obese adults with knee pain. In FAST, participants in either aerobic exercise program or a resistance exercise program demonstrated greater improvement in physical function at 18 months compared to participants in a health education control (9). In addition, evidence suggests that weight loss confers additional benefits upon function among obese adults with knee pain. In ADAPT (10), an 18-month combined exercise and dietary weight-loss intervention was effective in providing improvements in self-reported physical function and pain compared to a healthy lifestyle control condition. These findings are promising; however, developing safe, effective, and translatable behavioral interventions to improve long-term weight loss and reduce knee pain remains an ever-present challenge.

The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) study (12) is a multicenter, randomized clinical trial designed to investigate the long-term health effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) vs. usual care (Diabetes Support and Education, or DSE) among 5,145 overweight or obese adults, aged 45–74 years, with type 2 diabetes. Within this sample, 2,203 participants self-reported knee pain at baseline and thus were asked to respond in more detail regarding knee pain, stiffness, and physical function. The purposes of this investigation were (i) to determine whether participants in this subsample who were randomized into the ILI condition demonstrated greater improvement in self-reported physical function and knee pain from baseline to 12 months vs. those in the DSE condition, and (ii) to determine whether the effect of the ILI upon physical function was mediated by changes in weight or fitness level from baseline to 12 months.

Methods and Procedures

Participants and eligibility

Briefly, the total Look AHEAD sample included 5,145 overweight or obese adults (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 if currently taking insulin) with type 2 diabetes who were recruited from 16 outpatient centers in the United States. Recruitment for Look AHEAD began in September 2001, and a complete description of the design of Look AHEAD has been published (12).

All participants were required to successfully complete a 2-week behavioral run-in prior to randomization, in which they recorded daily information regarding diet and physical activity. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to either the DSE or the ILI intervention using a web-based data management system that verified eligibility. Randomization was stratified by clinical center and blocked with random block sizes. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before screening in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the guidelines of each center's Institutional Review Board. The sample for this investigation included 2,203 participants who reported knee pain at baseline.

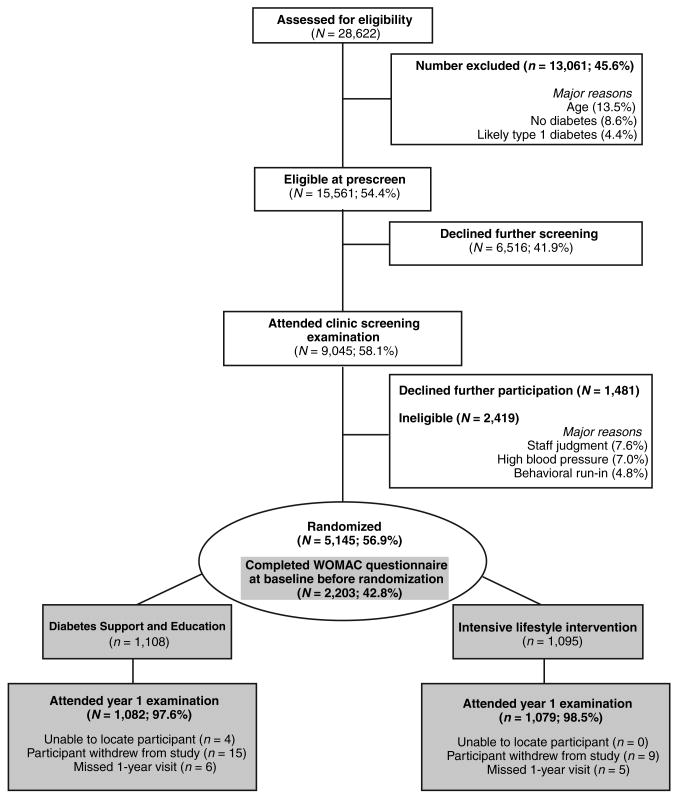

Participants in both the ILI condition and the DSE condition continued to receive general medical care and treatment for diabetes from their personal physicians. Figure 1 summarizes the enrollment and retention of participants from baseline to year 1 according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines. Details of the screening process for all participants (n = 5,145) are displayed in white background, whereas the 1-year retention of the 2,203 participants with knee pain at baseline (the focus of this investigation) is highlighted in gray background.

Figure 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials flowchart for enrollment of participants into the Look AHEAD Study. WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

ILI

The ILI has previously been described (13). Succinctly, the overall goal of the ILI was to teach and encourage behavioral change strategies regarding nutrition and physical activity to promote a mean weight loss of ≥10% of initial body weight by year 1 and increase moderate-intensity physical activity to ≥175 min/week by month 6. The ILI used a combination of group and individual sessions. During months 1–6 of the intervention, ILI participants attended three weekly group sessions, and one individual session with their lifestyle counselor each month, and were encouraged to replace two meals and one snack each day with liquid shakes and meal bars. During months 7–12, participants attended two group sessions and one individual session each month, and were encouraged to replace one meal per day. In addition, the ILI included options for a toolbox of behavioral strategies or pharmacotherapy (orlistat) that could be implemented for participants who were having difficulty meeting the minimal weight-loss goals.

DSE

Participants in the DSE condition received general recommendations related to healthy eating and physical activity, and safe and effective implementation of these recommendations for individuals with type 2 diabetes. Participants attended an initial prerandomization diabetes education session, and were invited to attend three additional group sessions during the first year that focused on topics related to nutrition, physical activity, and social support. However, in contrast to the ILI, DSE participants were not given specific strategies or goals to promote weight loss or physical activity, and did not receive individual sessions with a lifestyle counselor.

Outcome measures

Self-reported knee pain, stiffness, and physical function during the past 2 weeks were assessed via self-report at baseline before randomization and 1-year follow-up using a modified version of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) (14), an established and validated instrument to assess health status among older adults with knee OA. All participants were asked the question “Have you had any pain or discomfort in your knees in the past month?” Participants who responded “yes” to this item completed the WOMAC questionnaire. Participants who responded “no” did not complete the WOMAC questionnaire.

The WOMAC is a multidimensional measure of physical function disability, pain, and stiffness. The 5-item pain dimension score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater pain. The 2-item stiffness subscale score ranges from 0 to 8. The physical function dimension includes 17 questions regarding degree of difficulty in performing daily activities (e.g., descending stairs or rising from bed) due to knee pain or discomfort over the past 2 weeks. Individual scores of the 17 items are added to generate a summary score with a range from 0 to 68, with higher scores suggesting poorer function. Finally, the WOMAC summary score was calculated as the sum of the three subscale scores, with a range of 0 to 96. The Cronbach α coefficients to estimate internal consistency reliability for the pain, stiffness, and physical function were excellent (0.82, 0.80, and 0.95, respectively), as was that of the summary score (0.96).

Covariates

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; yes/no), and knee arthroscopy, knee replacement or hip replacement within 1 year of the baseline assessment (yes/no) were assessed via self-report. Weight was directly measured in duplicate using a standardized protocol. Metabolic equivalents (METs) at 80% of maximal heart rate were estimated from performance on a graded exercise treatment test of ∼10 min that also included heart rate measurement. Depressive symptoms were assessed via self-report using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (15), a validated instrument. Scores on the BDI-II range from 0 to 63, with higher scores suggesting more severe depressive symptoms.

Analyses

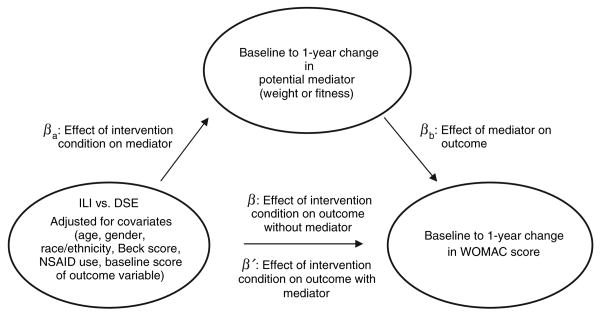

Preliminary descriptive statistics were performed to examine the baseline characteristics of the entire sample with knee pain (n = 2,203), partitioned according to intervention condition. To investigate the relationship between intervention condition, changes in weight or fitness, and changes in self-reported physical function and knee pain, we employed mediation analyses to test the effect of intervention (ILI vs. DSE) upon baseline to 12-month change upon each of the following variables: WOMAC pain subscale, WOMAC physical function subscale, WOMAC stiffness subscale, and WOMAC summary score. Each separate analysis included the following baseline covariates: baseline values of the outcome variable and mediator, age, gender (reference = male), ethnicity (reference = non-Hispanic white), BDI-II score, use of NSAIDs (reference = no), and study site. We also initially considered other covariates (presence of gout, knee or hip surgery, and an intervention × gender interaction term) that were not significant and thus were not retained in the final models. The mediation analyses used a modification of the widely used approach developed by Baron and Kenny (16), which entails three steps, shown in Figure 2; (i) conducting a multiple regression analysis to determine whether there is a significant relationship between the independent variable (intervention condition) and the outcome variables (WOMAC subscales; β); (ii) determining whether a significant relationship exists between the intervention condition and potential mediators (weight change or MET change; βa); and (iii) determining whether the addition of the mediator to the regression model in step 1 reveals a significant relationship between the mediator and the outcome variable (βb), and results in an attenuation of the significant effect between intervention condition and the outcome variables (β′). The Sobel test (17) was used to assess statistical significance. Adjusted means of change in weight and WOMAC scores were generated from path β of the mediation analyses for the two groups. For descriptive purposes, we also provide changes in raw means (s.d.) from baseline to 1 year with effect sizes, which were calculated by dividing the difference in means of the two groups by the pooled standard deviation. The high correlation between change in weight and change in fitness (Pearson r = 0.43; P < 0.001) prohibited the inclusion of both potential mediators in the same model. All mediation analyses were restricted to participants who had complete data for all variables (1,755 ≤ n ≤ 1,759). For all analyses, the type I error rate was set at α < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Figure 2.

Illustration of mediation analyses. DSE, Diabetes Support and Education; ILI, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of all participants who reported knee pain at baseline, partitioned by intervention. Collectively, DSE participants had a higher mean age, lower fitness expressed as METs, lower BDI scores, and higher prevalence of gout compared to ILI participants. The ILI and DSE conditions were similar with respect to gender, ethnicity, anthropometric measurements, WOMAC scores, NSAID use, and knee or hip surgery. In addition, 239 (21.8%) of the ILI participants received orlistat treatment during year 1.

Table 1. Baseline descriptive characteristics of ILI and DSE interventions among all participants with knee pain.

| Characteristics | DSE (n = 1,108) | ILI (n = 1,095) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years)a | 59.4 (7.0) | 58.8 (6.7) | 0.05 |

| Genderb | |||

| Men | 376 (33.9) | 396 (36.2) | 0.27 |

| Women | 732 (66.1) | 699 (63.8) | |

| Ethnicityb | |||

| African-American | 181 (16.3) | 202 (18.4) | 0.51 |

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 56 (5.1) | 53 (4.8) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10 (0.9) | 8 (0.7) | |

| Hispanic/Latino American | 113 (10.2) | 131 (12.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 723 (65.2) | 677 (61.8) | |

| Other/multiple | 25 (2.3) | 24 (2.1) | |

| Anthropometric/cardiovascular/metabolic | |||

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 37.2 (6.1) | 37.0 (6.2) | 0.43 |

| Weight (kg)a | 103.6 (19.1) | 102.1 (19.6) | 0.55 |

| Waist circumference (cm)a | 116.0 (13.5) | 115.4 (14.4) | 0.32 |

| Metabolic equivalents at 80% max heart rate (ml O2 × kg−1 × min−1 × 3.5) | 4.85 (1.46) | 4.97 (1.48) | 0.06 |

| Metabolic equivalents at 100% max heart rate (ml O2 × kg−1 × min−1 × 3.5) | 6.72 (1.84) | 6.89 (1.89) | 0.04 |

| %Hemoglobin A1c (mg/dl) | 7.28 (1.15) | 7.24 (1.11) | 0.41 |

| Health-related quality of life | |||

| Beck Depression Inventorya | 6.3 (4.7) | 6.8 (5.6) | 0.03 |

| Presence of goutb | 31 (2.8) | 16 (1.5) | 0.03 |

| WOMAC pain scalea | 3.9 (3.0) | 3.7 (2.9) | 0.08 |

| WOMAC stiffness scale | 1.89 (1.53) | 1.87 (1.48) | 0.73 |

| WOMAC physical function scalea | 11.5 (10.1) | 11.3 (9.9) | 0.66 |

| WOMAC summary score | 17.30 (13.53) | 16.86 (13.14) | 0.43 |

| Pain medication/surgery | |||

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use | 403 (36.4) | 378 (34.5) | 0.36 |

| Knee arthroscopy, or knee or hip replacement | 7 (0.6) | 14 (1.3) | 0.11 |

DSE, Diabetes Support and Education; ILI, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Data are presented as means (s.d.).

Data are presented as number (%).

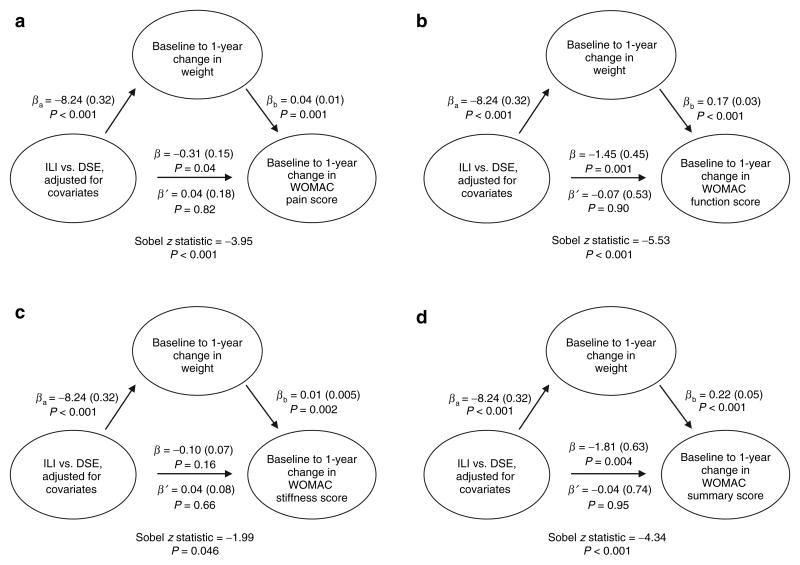

ILI participants reported more favorable change in WOMAC pain, function, and summary scores vs. DSE participants (Table 2 and Figure 3, path β), and demonstrated greater weight loss compared to DSE participants (Figure 3, path βa). In addition, increased weight (Figure 3, path βb) was significantly and unfavorably associated with WOMAC pain, function, stiffness, and summary scores, and the addition of weight change into the models attenuated the effect of the ILI intervention upon WOMAC scores (path β′). The Sobel scores were significant in all models (P < 0.05).

Table 2. Adjusted means of change in weight and WOMAC scores generated from mediation analyses, path β.

| Adjusted mean changea (s.e.) | P for difference | Raw mean change (s.d.) | Effect size for change between ILI and DSEb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) changea | N = 1,755 | |||

| DSE | −0.78 (0.49) | 0.001 | −0.90 (5.14) | −1.18 |

| ILI | −9.02 (0.48) | −9.08 (8.31) | ||

| WOMAC pain changec | N = 1,758 | |||

| DSE (n = 856) | −0.11 (0.23) | 0.04 | −0.28 (3.57) | 0.06 |

| ILI (n = 902) | −0.41 (0.22) | −0.51 (3.45) | ||

| WOMAC physical function changec | N = 1,759 | |||

| DSE (n = 857) | −1.28 (0.69) | 0.001 | −0.73 (11.32) | −0.15 |

| ILI (n = 902) | −2.73 (0.67) | −2.30 (9.92) | ||

| WOMAC stiffness subscale changec | N = 1,759 | |||

| DSE (n = 857) | −0.34 (0.11) | 0.16 | −0.24 (1.72) | −0.07 |

| ILI (n = 902) | −0.44 (0.11) | −0.36 (1.69) | ||

| WOMAC Summary Score changec | N = 1,759 | |||

| DSE (n = 857) | −1.73 (0.96) | 0.004 | −1.22 (15.34) | −0.13 |

| ILI (n = 902) | −3.54 (0.94) | −3.10 (13.57) |

DSE, Diabetes Support and Education; ILI, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, study site, Beck Depression Inventory Score, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and baseline weight.

Effect size calculated as (ILImean − DSEmean)/pooled standard deviation.

Adjusted for baseline values of outcome variable, age, gender, race/ethnicity, study site, Beck Depression Inventory Score, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and baseline weight.

Figure 3.

Summary of mediation analyses related to intervention, change in weight, and change in WOMAC scores. (a) Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC pain score (n = 1,755). (b) Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC function score (n = 1,756). (c) Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC stiffness score (n = 1,756). (d) Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC summary score (n = 1,756). β (s.e.) adjusted for baseline values of outcome variable, age, gender, race/ethnicity, study site, Beck Depression Inventory Score, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and baseline weight. βa, effect of intervention condition on mediator; β, effect of intervention condition on outcome without mediator; β′, effect of intervention condition on outcome with mediator; βb, effect of mediator on outcome; DSE, Diabetes Support and Education; ILI, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Other covariates that were significantly associated with less favorable change on all WOMAC subscales included age, female gender, NSAID use, and baseline weight (Table 3). African Americans reported less favorable change in the WOMAC pain score compared to non-Hispanic whites, and other/mixed race participants reported less favorable baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC pain, function, and summary compared to non-Hispanic whites. American Indians reported more favorable change in WOMAC function and stiffness compared to non-Hispanic whites. Higher baseline BDI-II scores were also associated with less favorable change in WOMAC function, stiffness, and summary scores.

Table 3. Parameter estimates for covariates in mediation analyses related to intervention condition, path β′.

| Regression parameter estimate (s.e.); P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Covariate | Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC pain (n = 1,755) | Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC function (n = 1,756) | Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC stiffness (n = 1,756) | Baseline to 1-year change in WOMAC summary (n = 1,756) |

| Age (years) | 0.02 (0.01); P = 0.05 | 0.10 (0.04); P = 0.006 | 0.02 (0.005); P = 0.001 | 0.12 (0.05); P = 0.01 |

| Female vs. male (reference) | 0.62 (0.17); P = 0.003 | 1.94 (0.53); P = 0.0002 | 0.37 (0.08); P < 0.001 | 2.67 (0.73); P = 0.001 |

| African-American vs. non-Hispanic white (reference) | 0.52 (0.22); P = 0.02 | 0.65 (0.66); P = 0.32 | 0.09 (0.10); P = 0.40 | 1.10 (0.91); P = 0.23 |

| Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic white (reference) | 0.20 (0.32); P = 0.55 | 1.05 (0.98); P = 0.28 | 0.12 (0.15); P = 0.44 | 1.12 (1.36); P = 0.41 |

| American Indian vs. non-Hispanic white (reference) | 0.30 (1.12); P = 0.79 | −6.67 (3.38); P = 0.05 | −0.96 (0.53); P = 0.07 | −7.48 (4.70); P = 0.11 |

| Asian vs. non-Hispanic white (reference) | −0.17 (0.85); P = 0.84 | −1.06 (2.56); P = 0.68 | −0.14 (0.40); P = 0.72 | −1.31 (3.56); P = 0.71 |

| Other or mixed races vs. non-Hispanic white (reference) | 1.22 (0.49); P = 0.01 | 3.47 (1.48); P = 0.02 | 0.36 (0.23); P = 0.12 | 5.02 (2.06); P = 0.01 |

| Baseline Beck Depression Inventory-II | 0.03 (0.01); P = 0.07 | 0.13 (0.05); P = 0.004 | 0.02 (0.01); P = 0.0004 | 0.15 (0.06); P = 0.02 |

| NSAID use vs. no NSAID use (reference) | 0.64 (0.16); P < 0.001 | 1.66 (0.49); P = 0.0007 | 0.30 (0.08); P < 0.001 | 2.36 (0.68); P = 0.005 |

| Baseline score of outcome variable | −0.54 (0.03); P < 0.001 | −0.51 (0.02); P < 0.001 | −0.58 (0.02); P < 0.001 | −0.47 (0.03); P < 0.001 |

| Baseline weight (kg) | 0.02 (0.004); P < 0.001 | 0.07 (0.01); P < 0.001 | 0.01 (0.002); P < 0.001 | 0.10 (0.02); P < 0.001 |

(s.e.) adjusted for intervention type and change in weight (kg) from baseline to 12 months.

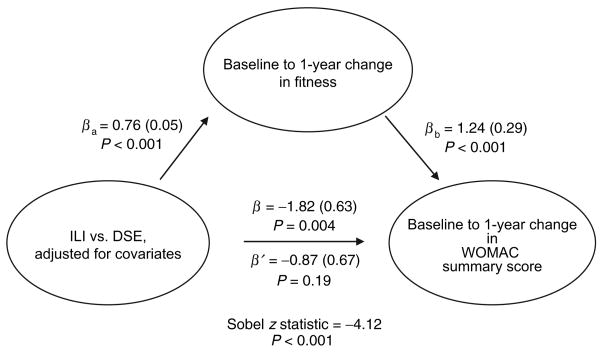

We performed additional analyses to determine whether changes in fitness mediated intervention condition effects upon WOMAC scores. These results were nearly identical to the analyses to test the potential mediational effect of weight change; thus, we present only the mediation analyses for WOMAC summary score (Figure 4). ILI participants demonstrated significantly better change in WOMAC summary score (path β), and greater improvement in fitness vs. DSE participants (path βa). Fitness change was favorably associated with WOMAC summary score (path βb), and attenuated the association between intervention condition effect and WOMAC summary score (path β′). The Sobel score was significant (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Summary of mediation analyses related to intervention, change in fitness, and WOMAC summary score. β (s.e.) adjusted for baseline values of outcome variable, age, gender, race/ethnicity, study site, Beck Depression Inventory Score, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and baseline metabolic equivalents (METs). βa, effect of intervention condition on mediator; β, effect of intervention condition on outcome without mediator; β′, effect of intervention condition on outcome with mediator; βb, effect of mediator on outcome; DSE, Diabetes Support and Education; ILI, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Discussion

The purposes of this investigation were to examine whether an ILI resulted in favorable change in knee pain and physical function among adults with diabetes who are overweight or obese, and whether the effect of intervention was mediated by changes in weight or fitness. Collectively, our results suggest that the ILI intervention was more effective than the DSE intervention in reducing pain and physical function as measured by the WOMAC questionnaire. Moreover, our findings suggest that the effect of the ILI intervention was mediated by changes in weight and fitness. This finding is unique in that we utilized a standardized assessment of knee pain in a large multiethnic sample that was not selected for clinical or radiographic evidence of knee OA.

Other studies that have focused on clinical samples have provided similar results. Messier et al. (10), studying 316 overweight or obese individuals with radiographic evidence of knee OA or chronic knee pain, demonstrated that an 18-month combined exercise and dietary weight-loss intervention was effective in providing improvements in self-reported physical function and pain compared to a healthy lifestyle control condition. Miller et al. (18) studied 87 older adults with symptomatic knee OA who were randomized into either a weight-stable or weight-loss condition for a 6-month trial. Participants in the weight-loss condition were prescribed a 1,000 kcal per day deficit diet with supervised, center-based exercise 3 days each week. Results indicated that participants in the weight-loss condition demonstrated greater weight loss, reported better function on the WOMAC scores, and exhibited greater 6-min walk distance than those in the weight-stable condition. Fransen and McConnell (19), in their review of 32 studies that incorporated land-based therapeutic exercise for participants with knee OA, found that studies that incorporated at least 12 direct supervision occasions demonstrated moderate effect sizes for reduction of pain and improvement of physical function.

The current study extends this work in a large population of overweight/obese individuals with type 2 diabetes by suggesting that weight loss and improvement in fitness were means through which the ILI intervention was associated with improved physical function. This finding is also plausible, based on the extant literature. Weight loss may result in improved physical function through several pathways. Messier et al. (20), studying ADAPT participants, found that for each 0.45 kg (1 pound) of weight lost, there was a corresponding fourfold reduction in the mechanical load exerted on the knee joint per step during daily activities. Similarly, Christensen et al. (21), in a meta-analysis of four intervention studies involving 454 overweight patients with knee OA, found that weight loss resulted in reduction in physical disability. Forsythe et al. (22), in a meta-analysis of 66 weight-loss interventions, found that weight loss was associated with decreases in inflammatory makers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, which have been associated with impaired physical function (23). There are also several possible mechanisms through which improved fitness may enhance physical function, including increased muscular strength in the muscles surrounding the knee joint (24,25), and reduced levels of inflammatory markers (26).

It is worthy of mention that although the goals of the ILI intervention (weight loss and increased physical activity) are similar to those of several other interventions among adults with obesity and knee pain, the ILI intervention was distinctive in that it did not involve supervised exercise sessions. The ILI consisted of a combination of group and individual counseling sessions regarding physical activity and nutrition for a total of 36 contacts over the first year. In contrast to structured, supervised exercise sessions, the ILI entailed a more collaborative approach between participants and interventionists to develop strategies for physical activity and nutrition, in which the participant assumed the responsibility for determining the types, times, and places of physical activity. This form of delivery marks an important difference between the before-mentioned exercise therapy interventions, which included a far more directive approach and involved structured, supervised center-based exercise sessions at a specific place and time, with specific forms of exercise that were directed by staff. Our results suggest that the ILI approach is effective and also offers more flexibility for participants and possibly less burden on staff. Similarly, Talbot et al. (24), in a small study of 34 older adults with symptomatic knee OA, found that a home-based, “Walk +” program was effective in increasing daily steps among participants at 12 weeks. The Walk + program incorporated an arthritis self-management program with counseling on increasing total pedometer steps by 10% every 4 weeks.

Other factors, such as increased self-efficacy (i.e., self-confidence), may also have influenced appraisal of physical function among ILI participants. In the OASIS study (11), participants with low self-efficacy and low knee strength at baseline exhibited the greatest decline in self-reported physical function at 30 months. In the FAST study, knee pain and self-efficacy were shown to mediate the effect of the aerobic exercise and resistance training groups on stair-climb time (27). According to Albert Bandura, the founder of Social Cognitive Theory (28), self-efficacy may be enhanced by several sources, such as performance accomplishments, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and interpretation of physiological sensations. The ILI intervention, with its combination of group and individual counseling, provided a setting to provide regular feedback to ILI participants regarding their progress toward meeting their goals, encouragement by the interventionists and other participants, comparative appraisal of other group members' progress, and development of problem-solving strategies to prevent or address lapses. Thus, it is conceivable that the weight-loss and fitness changes of ILI participants were coupled with perceptual changes that favorably influenced their assessment of their physical function.

The Look AHEAD trial is being conducted in persons with diabetes; however, these results are expected to be generalizable to a nondiabetic population. For example, the weight loss observed in Look AHEAD (29) is similar to that observed in other studies among nondiabetic populations (30–33), and the goals set for this trial are similar to those set for the general population. For instance, the ILI goal of ≥175 min of moderate- intensity physical activity per week is similar to the recommendations of both the US Department of Health and Human Services (34), and the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association (35) that recommend that adults perform at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week. Similarly, the weight-loss goal of ≥10% is in accordance with the NHLBI Clinical Guidelines on identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity among adults, which asserts that ≥10% weight loss within 6 months of beginning a weight management program is a reasonable goal (36). Also, the use of toolbox behavioral strategies to deal with barriers may be tailored to set goals among individuals without diabetes. In addition, the use of both group-mediated and individual sessions may be used in several settings and populations.

This investigation was not without limitations, the foremost of which was the lack of radiographic evidence of knee OA to corroborate participants' self-report of knee pain. However, knee pain or knee function were not primary end points of Look AHEAD, and there were no criteria regarding baseline knee pain; thus, we relied upon self-report for measures of knee pain and physical function. We also did not include several covariates in our models that may be associated with knee pain, such as vitamin K serum levels (37) and self-efficacy. We also did not include inflammatory factors, which were only assessed in half of the Look AHEAD sample. Our nonsignificant finding of the effect of the ILI on the stiffness dimension may, in part, be due to the fact that this dimension only has two items. In addition, the small effect sizes observed may to some extent reflect the low baseline scores for pain, stiffness, and function in both groups, which in turn may be reflective of the fact that participants were recruited into Look AHEAD without regard to knee pain. Also, although the Look AHEAD sample is multiethnic, the generalizability of our findings is limited due to the fact that this sample has at least three comorbid conditions (knee pain, overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes), and all of the clinical sites were located in urban (not rural) settings.

Conclusion

The ILI resulted in improved physical function among overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes and knee pain. Moreover, this effect was observed after adjustment for several potential demographic and clinical confounders, and it was mediated by changes in both weight and fitness levels, which were two major goals of the ILI group. These findings are consistent with other studies among similar samples, in which exercise and diet interventions resulted in improvements in physical function. The ILI focused on group and individual counseling without supervised exercise training, which may be a cost-effective delivery strategy. The results of this study give further support to current physical activity and weight-loss recommendations for adults with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and knee pain, and prompt further research regarding the translatability and cost-effectiveness of the ILI.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women's Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IHS or other funding sources. Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (M01RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the University of Washington/VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346). The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; Optifast of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

Appendix: Look Ahead Research Group at Year 1

2 November 2009

Clinical sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS (Principal Investigator); Jeff Honas, MS (Program Coordinator); Lawrence Cheskin, MD (Co-Investigator); Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH (Co-Investigator); Kerry Stewart, EdD (Co-Investigator); Richard Rubin, PhD (Co-Investigator); Jeanne Charleston, RN; Kathy Horak, RD.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center

George A. Bray, MD (Principal Investigator); Kristi Rau (Program Coordinator); Allison Strate, RN (Program Coordinator); Brandi Armand, LPN (Program Coordinator); Frank L. Greenway, MD (Co-Investigator); Donna H. Ryan, MD (Co-Investigator); Donald Williamson, PhD (Co-Investigator); Amy Bachand; Michelle Begnaud; Betsy Berhard; Elizabeth Caderette; Barbara Cerniauskas; David Creel; Diane Crow; Helen Guay; Nancy Kora; Kelly LaFleur; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Mandy Shipp, RD; Marisa Smith; Elizabeth Tucker.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham

C.E.M., MD, MSPH (Principal Investigator); Sheikilya Thomas, MPH (Program Coordinator); Monika Safford, MD (Co-Investigator); Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Stacey Gilbert, MPH; Stephen Glasser, MD; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jennifer Jones, MA; DeLavallade Lee; Ruth Luketic, MA, MBA, MPH; Karen Marshall; L. Christie Oden; Janet Raines, MS; Cathy Roche, RN, BSN; Janet Truman; Nita Webb, MA; Audrey Wrenn, MAEd.

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital

David M. Nathan, MD (Principal Investigator); Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE (Program Coordinator); Kristina Schumann, BA (Program Coordinator); Enrico Cagliero, MD (Co-Investigator); Linda Delahanty, MS, RD (Co-Investigator); Kathryn Hayward, MD (Co-Investigator); Ellen Anderson, MS, RD (Co-Investigator); Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Richard Ginsburg, PhD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Charles McKitrick, RN, BSN, CDE; Alan McNamara, BS; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc CCS; Alexi Poulos, BA; Barbara Steiner, EdM; Joclyn Tosch, BA.

Joslin Diabetes Center

Edward S. Horton, MD (Principal Investigator); Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE (Program Coordinator); Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD (Co-Investigator); A. Enrique Caballero, MD (Co-Investigator); Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

George Blackburn, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc (Co-Investigator); Kristinia Day, RD; Ann McNamara, RN.

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center

James O. Hill, PhD (Principal Investigator); Marsha Miller, MS, RD (Program Coordinator); JoAnn Phillipp, MS (Program Coordinator); Robert Schwartz, MD (Co-Investigator); Brent Van Dorsten, PhD (Co-Investigator); Judith Regensteiner, PhD (Co-Investigator); Salma Benchekroun, MS; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Elizabeth Daeninck, MS, RD; Amy Fields, MPH; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy; Michael McDermott, MD; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS; Loretta Rome, TRS; Kristin Wallace, MPH; Terra Worley, BA.

Baylor College of Medicine

John P. Foreyt, PhD (Principal Investigator); Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD (Program Coordinator); Henry Pownall, PhD (Co-Investigator); Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS (Co-Investigator); Peter Jones, MD (Co-Investigator); Michele Burrington, RD; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD; Allyson Clark, RD; Molly Gee, MEd, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Jayne Joseph, RD; Patricia Pace, RD; Julieta Palencia, RN; Olga Satterwhite, RD; Jennifer Schmidt; Devin Volding, LMSW; Carolyn White.

University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine

Mohammed F. Saad, MD (Principal Investigator); Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD (Program Coordinator); Ken C. Chiu, MD (Co-Investigator); Medhat Botrous; Michelle Chan, BS; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Magpuri Perpetua, RD.

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee East

Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH (Principal Investigator); Carolyn Gresham, RN (Program Coordinator); Stephanie Connelly, MD, MPH (Co-Investigator); Amy Brewer, RD, MS; Mace Coday, PhD; Lisa Jones, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN; Shirley Vosburg, RD, MPH; and J. Lee Taylor, MEd, MBA.

University of Tennessee Downtown

Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD (Principal Investigator); Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN (Program Coordinator); Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT; Gracie Cunningham; Donna Green, RN; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Robert Kores, PhD; Renate Rosenthal, PhD; Elizabeth Smith, MS, RD, LDN; Maria Sun, MS, RD, LDN; Judith Soberman, MD (Co-Investigator).

University of Minnesota

Robert W. Jeffery, PhD (Principal Investigator); Carolyn Thorson, CCRP (Program Coordinator); John P. Bantle, MD (Co-Investigator); J. Bruce Redmon, MD (Co-Investigator); Richard S. Crow, MD (Co-Investigator); Scott Crow, MD (Co-Investigator); Susan K. Raatz, PhD, RD (Co-Investigator); Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Jeanne Carls, MEd; Tara Carmean-Mihm, BA; Emily Finch, MA; Anna Fox, MA; Elizabeth Hoelscher, MPH, RD, CHES; La Donna James; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh CHES; Tricia Skarphol, BS; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD.

St Luke's Roosevelt Hospital Center

Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD (Principal Investigator); Jennifer Patricio, MS (Program Coordinator); Stanley Heshka, PhD (Co-Investigator); Carmen Pal, MD (Co-Investigator); Lynn Allen, MD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN.

University of Pennsylvania

Thomas A. Wadden, PhD (Principal Investigator); Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE (Program Coordinator); Stanley Schwartz, MD (Co-Investigator); Gary D. Foster, PhD (Co-Investigator); Robert I. Berkowitz, MD (Co-Investigator); Henry Glick, PhD (Co-Investigator); Shiriki K. Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH (Co-Investigator); Johanna Brock; Helen Chomentowski; Vicki Clark; Canice Crerand, PhD; Renee Davenport; Andrea Diamond, MS, RD; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Louise Hesson, MSN; Stephanie Krauthamer-Ewing, MPH; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Monica Mullen, MS, RD; Leslie Womble, PhD, MS; Nayyar Iqbal, MD.

University of Pittsburgh

David E. Kelley, MD (Principal Investigator); Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE (Program Coordinator); Lewis Kuller, MD, DrPH (Co-Investigator); Andrea Kriska, PhD (Co-Investigator); Janet Bonk, RN, MPH; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD (Co-Investigator); Mary L. Klem, PhD, MLIS (Co-Investigator); Monica E. Yamamoto, DrPH, RD, FADA (Co-Investigator); Barb Elnyczky, MA; George A. Grove, MS; Pat Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Janet Krulia, RN, BSN,CDE; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Anne Mathews, MS, RD, LDN; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Joan R. Ritchea; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Karen Vujevich, RN-BC, MSN, CRNP; Donna Wolf, MS.

The Miriam Hospital/Brown Medical School

Rena R. Wing, PhD (Principal Investigator); Renee Bright, MS (Program Coordinator); Vincent Pera, MD (Co-Investigator); J.H.J., PhD (Co-Investigator); Deborah Tate, PhD (Co-Investigator); Amy Gorin, PhD (Co-Investigator); Kara Gallagher, PhD (Co-Investigator); Amy Bach, PhD; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Tatum Charron, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Maureen Daly, RN; Caitlin Egan, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Linda Foss, MPH; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Don Kieffer, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; JP Massaro, BS; Tammy Monk, MS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Deborah Robles; Jane Tavares, BS.

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

Steven M. Haffner, MD (Principal Investigator); Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE (Program Coordinator); Carlos Lorenzo, MD (Co-Investigator).

University of Washington/VA Puget Sound Health Care System

Steven Kahn, MB, ChB (Principal Investigator); Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE (Program Coordinator); Robert Knopp, MD (Co-Investigator); Edward Lipkin, MD (Co-Investigator); Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD (Co-Investigator); Dace Trence, MD (Co-Investigator); Terry Barrett, BS; Joli Bartell, BA; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Anne Murillo, BS; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; April Thomas, MPH, RD.

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona, Shiprock, New Mexico

William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH (Principal Investigator); Paula Bolin, RN, MC (Program Coordinator); Tina Killean, BS (Program Coordinator); Cathy Manus, LPN (Co-Investigator); Jonathan Krakoff, MD (Co-Investigator); Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH (Co-Investigator); Justin Glass, MD (Co-Investigator); Sara Michaels, MD (Co-Investigator); Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP (Co-Investigator); Tina Morgan (Co-Investigator); Shandiin Begay, MPH; Bernadita Fallis, RN, RHIT, CCS; Jeanette Hermes, MS, RD; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP-C, CDE; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Janelia Smiley; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC; Christina Tomchee, BA; Darryl Tonemah PhD.

University of Southern California

Anne Peters, MD (Principal Investigator); Valerie Ruelas, MSW, LCSW (Program Coordinator); Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD (Program Coordinator); Kathryn Graves, MPH, RD, CDE; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Sara Serafin-Dokhan.

Coordinating center

Wake Forest University

Mark A. Espeland, PhD (Principal Investigator); Judy L. Bahnson, BA (Program Coordinator); L.E.W., DrPH (Co-Investigator); David Reboussin, PhD (Co-Investigator); W.J.R., PhD (Co-Investigator); Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH (Co-Investigator); W.L., PhD (Co-Investigator); G.D.M., PhD (Co-Investigator); David Lefkowitz, MD (Co-Investigator); Patrick S. Reynolds, MD (Co-Investigator); P.M.R., PhD (Co-Investigator); Mara Vitolins, DrPH (Co-Investigator); C.G.F. (Co-Investigator), Michael Booth, MBA (Program Coordinator); Kathy M. Dotson, BA (Program Coordinator); Amelia Hodges, BS (Program Coordinator); Carrie C. Williams, BS (Program Coordinator); Jerry M. Barnes, MA; Patricia A. Feeney, MS; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; William Herman, MD, MPH; Patricia Hogan, MS; Sarah Jaramillo, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca Neiberg, MS; Andrea Ruggiero, MS; Christian Speas, BS; M.P.W., MS; Karen Wall, AAS; Michelle Ward; Delia S. West, PhD; Terri Windham.

Central resources centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco

Michael Nevitt, PhD (Principal Investigator); Susan Ewing, MS; Cynthia Hayashi; Jason Maeda, MPH; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA; Michaela Rahorst; Ann Schwartz, PhD; John Shepherd, PhD.

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories

Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD (Principal Investigator); Greg Strylewicz, MS.

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Ronald J. Prineas, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Teresa Alexander; Lisa Billings; Charles Campbell, AAS, BS; Sharon Hall; Susan Hensley; Yabing Li, MD; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD.

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities

Elizabeth J. Mayer-Davis, PhD (Principal Investigator); Robert Moran, PhD.

Hall-Foushee Communications, Inc.

Richard Foushee, PhD; Nancy J. Hall, MA.

Federal sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD, PhD; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Jeffrey Cutler, MD, MPH; Eva Obarzanek, PhD, MPH, RD.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Edward W. Gregg, PhD; David F. Williamson, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD.

All other Look AHEAD staffs are listed alphabetically by site.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2087–2102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1581–1586. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:961–969. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oguma Y, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Lee IM. Weight change and risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Obes Res. 2005;13:945–951. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magliano M. Obesity and arthritis. Menopause Int. 2008;14:149–154. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felson DT. The sources of pain in knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:624–628. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000172800.49120.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JL, O'Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575–588. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, et al. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:914–918. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettinger WH, Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) JAMA. 1997;277:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1501–1510. doi: 10.1002/art.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rejeski WJ, Miller ME, Foy C, Messier S, Rapp S. Self-efficacy and the progression of functional limitations and self-reported disability in older adults with knee pain. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:S261–S265. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.5.s261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, et al. The Look AHEAD Research Group. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Look AHEAD Research Group. Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, et al. The Look AHEAD Study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH. Validation study of the WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antiheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology 1982. American Sociological Association; Washington, DC: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, Davis C, et al. Intensive weight loss program improves physical function in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1219–1230. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fransen M, McConnell S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD004376. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2026–2032. doi: 10.1002/art.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:433–439. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsythe LK, Wallace JM, Livingstone MB. Obesity and inflammation: the effects of weight loss. Nutr Res Rev. 2008;21:117–133. doi: 10.1017/S0954422408138732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penninx BW, Abbas H, Ambrosius W, et al. Inflammatory markers and physical function among older adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2027–2031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talbot LA, Gaines JM, Huynh TN, Metter EJ. A home-based pedometer-driven walking program to increase physical activity in older adults with osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:387–392. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urquhart DM, Soufan C, Teichtahl AJ, et al. Factors that may mediate the relationship between physical activity and the risk for developing knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:203. doi: 10.1186/ar2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen AM, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1154–1162. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rejeski WJ, Ettinger WH, Jr, Martin K, Morgan T. Treating disability in knee osteoarthritis with exercise therapy: a central role for self-efficacy and pain. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:94–101. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). TONE Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 1998;279:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with high-normal blood pressure. The Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:657–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. [Accessed 29 March 2010];2008 < http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx>.

- 35.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1423–1434. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Heart LaBI. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neogi T, Booth SL, Zhang YQ, et al. Low vitamin K status is associated with osteoarthritis in the hand and knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1255–1261. doi: 10.1002/art.21735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]