Abstract

Background

Alterations at the level of the coronary circulation with aging may play an important role in the evolution of age-associated changes in left ventricular (LV) fibrosis and function. However these age-associated changes in the coronary vasculature remain poorly defined primarily due to the lack of high resolution imaging technologies. The current study was designed to utilize cardiac micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) technology as a novel imaging strategy, to define the three dimensional coronary circulation in the young and aged heart and its relationship to LV fibrosis and function.

Method and Results

Young (2 month old; n=10) and aged (20 month old; n=10) Fischer rats underwent cardiac micro-CT imaging as well as echocardiography, blood pressure and fibrosis analysis. Importantly when indexed to LV mass which increased with age, the total and intramyocardial vessel volumes were lower, while the epicardial vessel volume, with and without indexing to LV mass, was significantly higher in the aged hearts compared to the young hearts. Moreover the aged hearts had a significantly lower percentage of intramyocardial vessel volume and a significantly higher percentage of epicardial vessel volume, when normalized to the total vessel volume, compared to the young hearts. Further, the aged hearts had significant LV fibrosis and mild LV dysfunction compared to the young hearts.

Conclusions

This micro-CT imaging study reports the reduction in normalized intramyocardial vessel volume within the aged heart, in association with increased epicardial vessel volume, in the setting of increased LV fibrosis and mild LV dysfunction.

Keywords: computed tomography, aging, coronary vasculature, fibrosis

The aged myocardium is characterized by a reduction in cardiomyocyte number 1, an increase in fibrosis 2-4 and an increase in mass. 5 Importantly, excessive accumulation of collagen is a major determinant of increased myocardial stiffness which contributes to diastolic and systolic dysfunction leading to the rise in heart failure commonly seen in the elderly. 6 While advances have been made in our understanding of molecular pathways 3, 7, 8, alterations in collagen turnover 9 and changes in hemodynamics 10 that contribute to age-associated cardiac fibrosis, the potential alterations in the coronary circulation with aging is not fully defined.

Importantly, changes at the level of the coronary circulation with aging may play a critical role in the evolution of impaired myocardial function as a consequence of cardiac fibrosis or even as a primary mediator of structural changes of the heart secondary to the consequences of reduced myocardial perfusion. Although a decrease in coronary capillary density with aging has been previously reported by histomorphometric analysis, 11 the influence of age on the intramyocardial and epicardial vasculature of varying luminal diameters remains poorly defined, primarily due to the lack of sensitive imaging technologies.

Cardiac micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) is a sensitive and high resolution technique that permits studies of small scale structures, particularly the microcirculation within organs. 12-15 This advance in medical imaging technology provides the ability to define structural alterations of the myocardial coronary vasculature during aging which will enhance our understanding of age-associated changes in the heart which goes beyond histomorphometric analysis.

The present study was therefore designed to define the myocardial volume of intramyocardial and epicardial vessels, throughout a range of luminal diameters, in an experimental Fischer rat model of aging using cardiac micro-CT imaging. We hypothesized that the total and intramyocardial vessel volume in the aged heart when normalized for increased LV mass would be lower, while the epicardial vessel volume would be higher, than that of the young heart. We further hypothesized that there would be a decrease in the percentage of intramyocardial vessel volume normalized to total vessel volume in the aged heart, compared to the young heart, and this reduction would be associated with an increase in LV fibrosis together with mild LV dysfunction. Thus the current study was designed to employ cardiac micro-CT technology as a novel imaging strategy in order to define the three dimensional (3-D) coronary circulation in the young and aged heart and to also advance our understanding of global myocardial aging.

Methods

Animals

Studies were performed in young (2 month old; n=10) and aged (20 month old; n=10) male Fischer rats (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Madison, WI). These age groups are equivalent to humans in their adolescence and in their 6th decade of life. 3 In each age group of 10 rats, 5 were used for micro-CT imaging and 5 were used for echocardiography, blood pressure (BP) measurement and histological analysis. The experimental study was performed in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and with approval of the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Micro-CT Imaging

Rats were anesthetized (1.5% isoflurane in oxygen) to permit hearts to be prepared based on a modification of a previously reported methodology. 13 First, the jugular vein (JV) and the carotid artery (CA) were cannulated with PE-90 tubing containing heparin (5000 units/ml). Then 1ml of heparin (5000 units/ml) was slowly infused via the JV and allowed to circulate for 30 minutes. After 30 minutes, the abdominal aorta (AA) below the renal vessels were exposed, separated from the surrounding tissue and inferior vena cava (IVC). The JV tubing was then connected to a 20 ml syringe containing heparinized saline (10 units/ml). The syringe was place in a syringe pump and the flow rate was set to maintain an infusion pressure of 30 mmHg. The syringe pump was turned on as the AA was cut and heparinized saline (10 units/ml) was infused via the JV cannula. Once the aortic effluent became clear, a small incision was made in the diaphragm and the thoracic aorta was clamped with a hemostat. Heparinized saline (10 units/ml) was then infused via the cannulated CA, maintaining an infusion pressure of 60 mmHg, as the effluent drained out the open-ended JV catheter. Once the JV effluent became clear, an intravascular contrast agent, radiopaque microfil silicon-based polymer (MV-122. Flowtech, Carver, MA) was then infused into the CA, at a flow rate that maintained an infusion pressure of 80 mmHg. Once the microfil polymer appeared in the IVC or JV, all cannulas were clamped and the rat was placed in a 4°C refrigerator overnight to allow for complete relaxation and the setting of the microfil polymer. The hearts were harvested the next day and prepared for scanning on a high resolution, volumetric custom build micro-CT scanner as previously described. 13 The isolated microfil injected rat hearts were mounted on a computer-controlled rotating stage so that an X-ray projection image was generated on a CsI crystalline plate, which converted the X-ray into a light-image, at each of 360 angles of view around 360 degrees. This image was optically projected onto a CCD imaging array which converted the light intensity on each of the 1024 × 1024 array of 24 μm on-a-side square pixels to an electronic signal proportional to the light (X-ray) intensity. The data, once recorded, were subjected to modified Feldkamp cone beam reconstruction algorithm 16 to generate a 3-D volume data set. The 3-D image consisted of up to 10243 cubic voxels, each 20 μm3 on a side, with gray scale equal to the X-ray attenuation coefficient in units of 1000/cm.

Micro-CT Analysis

The 3-D images (up to 10243 cubic voxels) were displayed with a maximum intensity projection method so that the coronary vessels show up as illustrated in Figure 1A & 1B and visualized with the Analyze software package (Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). 17 Our micro-CT analysis software was set up so that structures < 20 μm in diameter (i.e., the capillaries, terminal arterioles and smallest venules) were not visible on the CT image. As such the arterial and venous trees were “not connected” in this display image. The image analyst then identified the coronary arteries at the level of the aortic root and then applied a “connect” function on the analysis software which connects only those voxels in the arterial tree and not the venous tree. This arterial tree display was used to identify the location along the coronary vessels where the epicardial vessels converted to intramyocardial vessels. Using the same grey-scale threshold value to differentiate the blood vessels from the surrounding tissues an “erode/dilate’ image analysis methodology was used to estimate the intravascular lumen volume of vessels within a selected lumen diameter range by counting the number of voxels within the segmented arterial tree. As the cubic voxel side dimension was 20 μm, the coronary arterial lumen diameters were always derived in 40 μm increments. Coronary vessel volumes by luminal diameter from 80-760 μm assessed. As the transition point of which the epicardial vessels penetrated the myocardium and became intramyocardial vessels was within the range of 320-360 μm in luminal diameters, intramyocardial vessels were defined as luminal diameters from 80-360 μm and epicardial vessels were defined as luminal diameters from 361-760 μm. To avoid errors in arterial vessel lumen diameter estimates due to tomographic image blurring and partial volume effects, coronary vessels < 80 μm were excluded from our quantitative analysis.

Figure 1.

A representative 3-D maximum intensity micro-CT projection image of the young (A) and aged (B) Fischer heart with Microfil contrast agent injected into the coronary arteries. Figures 1C and 1D are representative computer generated renderings of the opacified lumens of the coronary vessels in a young (C) and aged (D) Fischer rat heart. The epicardial vessels are displayed in red and the intramyocardial vessels are displayed in blue.

Standard and Two-Dimensional Speckle-Derived Strain Echocardiography (2DSE)

As previously described, 3 standard transthoracic echocardiography was performed on anesthetized (1.5% isoflurane in oxygen) rats using the Vivid 7 ultrasound system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and a 10S transducer (11.5 MHz) with ECG monitoring. M-mode images and gray scale 2-D parasternal short axis images (300-350 frames /sec) at the mid-papillary level were recorded for off-line analysis using EchoPAC software (EchoPAC PC BTO 9.0.0, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). LV end-diastolic and end-systolic internal diameters and wall thicknesses were measured from M-mode images permitting calculation of LV ejection fraction (EF) based on the cubed method, LV mass and relative wall thickness (RWT). All parameters represent the average of 3 beats.

2DSE parasternal short axis images at the mid-papillary level were acquired with a frame rate ranging from 60 (full apical views) and 160 (narrow sector views) frames/second. Three consecutive cardiac cycles were recorded as 2-D cine loops and the acquired raw data were saved for off-line analysis using EchoPAC software. Circumferential systolic peak values were determined for strain (sS) and strain rate (sSR). Circumferential early diastolic peak values were determined for myocardial strain rate (dSR-E).

Blood Pressure and Fibrosis Analysis

After echocardiography, PE-50 tubing containing heparinized saline (10units/ml) was placed into the CA, in anesthetized (1.5% isoflurane in oxygen) rats, for BP acquisition using CardioSOFT Pro software (Sonometrics Corporation, London, Ontario). After BP acquisition, the hearts were then removed, the LV was dissected and a mid-LV cross section was preserved in 10% formalin for fibrosis analysis. Fixed LV tissues (n=5 per age group) were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at thickness of 4 µm. Collagen and extent of fibrosis was performed using picrosirius red staining. An Axioplan II KS 400 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Germany) was used to capture at least 4 randomly selected myocardial images, between the sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial regions, from each slide using a 20x objective. KS 400 software was utilized to determined fibrotic area as a percentage of total tissue area.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Student unpaired t tests were employed for single comparisons between age groups. Mean differences between the aged and young groups are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI) on these differences that were calculated using pooled standard deviations. Due to the suspected differences of vessel distribution between intramyocardial and epicardial vessels among young and aged hearts, separate analyses were done within these vessel age groups. In order to compare vessel volume across the range of vessel luminal diameters within each vessel age group, a generalized linear mixed model analyses, including a random per rat intercept term and an exchangeable correlation structure to control for repeated measurements within rats, were used to compare the percent vessel volume normalized to total vessel volume. To test for ordinal trend across vessel luminal diameters, a numeric value was assigned to each vessel diameter and this new variable was used in the analysis. Specifically, normalized vessel volume was modeled as a linear function of ordinal vessel diameter and age group within the mixed model framework while controlling for the repeated measurements at different vessel diameters within each rat. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used to fit the linear mixed models. Other analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was accepted as P<0.05.

Results

Coronary Vasculature

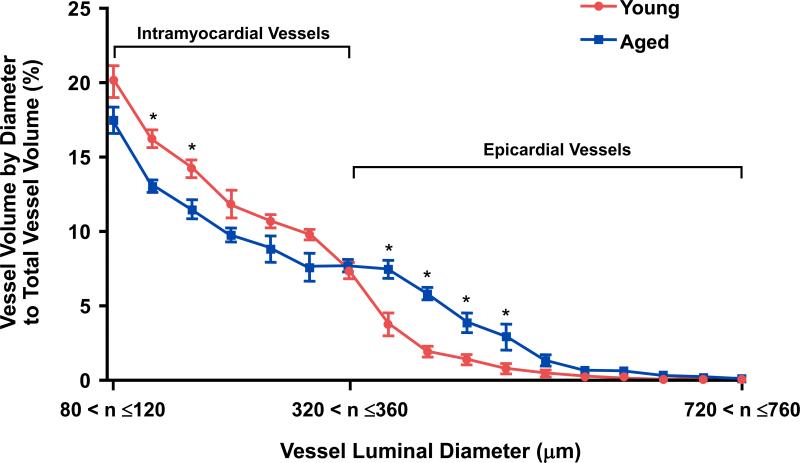

The micro-CT derived total, intramyocardial and epicardial coronary vessel volumes, including indexed to LV mass, are reported in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively. In Table 1, the total and epicardial vessel volumes were significantly higher in the aged heart compared to the young heart, with no change in the intramyocardial vessel volume between the age groups. However, when indexed to LV mass, the total and intramyocardial vessel volumes were significantly lower in the aged heart compared with the young heart as shown in Table 2. Whereas the epicardial vessel volume normalized to LV mass was significantly higher in the aged heart compared to the young heart (Table 2). Figures 1C & 1D illustrate a representative cardiac micro-CT reconstruction image of the coronary arterial vessels in the young (Figure 1C and Supplemental Movie 1) and aged (Figure 1D and Supplemental Movie 2) heart. The distribution percentage of vessel volume across a range of vessel luminal diameters, from 80-760 μm, normalized to total vessel volume is illustrated in Figure 2. When normalized vessel volume was modeled as a function of vessel diameter and age, on average the aged hearts had significantly lower normalized intramyocardial vessel volume (P=0.002) and a significantly higher normalized epicardial vessel volume (P<0.001) compared to the young hearts. Of note, the increase in normalized epicardial vessel volume was primarily due to an increase in vessel volumes between 361-520 μm. Moreover, there was very little vessel volume (<1% of the total) in vessel diameters above 640 μm for either age group. Figure 3 report the mean percent values for intramyocardial (Figure 3A) and epicardial (Figure 3B) vessel volumes in young and aged rats. When normalized to the total vessel volume, the aged heart had a significantly lower percentage of intramyocardial vessel volume (Figure 3A) and a significantly higher percentage of epicardial vessel volume (Figure 3B) compared to the young heart.

Table 1.

Micro-CT Derived Vessel Volumes

| Parameter | Young | Aged | Mean Difference# (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Vessel Volume (mm3) | 12.9 ± 0.5 | 17.2 ± 1.5* | 4.3 (0.6, 8.1) |

| Intramyocardial Vessel Volume (mm3) | 11.7 ± 0.3 | 13.1 ± 1.1 | 1.5 (-1.1, 4.0) |

| Epicardial Vessel Volume (mm3) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.6* | 2.9 (1.4, 4.5) |

Values are mean ± SE. n=5 for both age groups.

P<0.05.

Difference calculated as (Aged-Young).

Total Vessel Volume Diameters = 80-760 μm; Intramyocardial Vessel Volume Diameters = 80-360 μm; Epicardial Vessel Volume Diameters = 361-760 μm.

Table 2.

Micro-CT Derived Vessel Volumes Indexed to LV Mass

| Parameter | Young | Aged | Mean Difference# (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Vessel Volume/LV Mass (mm3/g) | 27.8 ± 0.9 | 21.2 ± 1.9* | -6.6 (-11.5, -1.8) |

| Intramyocardial Vessel Volume/ LV Mass (mm3/g) | 25.2 ± 0.5 | 16.1 ± 1.3* | -9.1 (-12.3, -6.0) |

| Epicardial Vessel Volume/LV Mass (mm3/g) | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.7* | 2.5 (0.3, 4.8) |

Values are mean ± SE. n=5 for both age groups.

P<0.05.

Difference calculated as (Aged-Young).

Total Vessel Volume Diameters = 80-760 μm; Intramyocardial Vessel Volume Diameters = 80-360 μm; Epicardial Vessel Volume Diameters = 361-760 μm.

Figure 2.

Graph illustrating the quantitative assessment of the percent vessel volume by diameter normalized to total vessel volume in young and aged hearts. As the voxel size was 20 μm, the diameter vessel range is in 40 μm increments for each point on the graph. Values are mean ± SE. n=5 for both age groups. *P<0.05 at the specific vessel luminal diameter.

Figure 3.

Graphs illustrating the mean percent values of intramyocardial vessel volume (A) and epicardial vessel volume (B) normalized to total vessel volume. Values are mean ± SE. n=5 for both age groups. *P<0.05.

LV Structure and Function and Blood Pressure

LV structure and function and mean arterial pressure (MAP) are reported in Table 3. There was a significant increase in body mass, LV mass, end-diastolic internal chamber diameter and RWT in the aged rats compared to the young rats. Moreover, left ventricle weight to body weight ratio was significantly lower in the aged rats compared to the young rats. Importantly, LVEF was significantly reduced and 2DSE confirmed significant impairment of systolic and diastolic function as demonstrated by reductions in circumferential sS, sSR and dSR-E in the aged heart. Further, the aged rat exhibited a significant increase in MAP and there was no difference in heart rate between the age groups.

Table 3.

Standard Cardiovascular Characteristics

| Parameter | Young | Aged |

|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 206 ± 2 | 439 ± 11* |

| LV Mass (mg) | 464 ± 10 | 818 ± 26* |

| LVW:BW (mg/g) | 2.24 ± 0.04 | 1.76 ± 0.02* |

| LVIDd (mm) | 6.73 ± 0.10 | 7.39 ± 0.10* |

| RWT | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.02* |

| EF (%) | 87 ± 1 | 80 ± 1* |

| sS Circ (%) | -23.6 ± 1.6 | -18.3 ± 1.5* |

| sSR Circ (1/s) | -6.2 ± 0.4 | -4.8 ± 0.3* |

| dSR-E Circ. (1/s) | 7.6 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.1* |

| HR (bpm) | 275 ± 4 | 278 ± 9 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 90 ± 2 | 98 ± 1* |

Values are mean ± SE. n=5 for both age groups.

P<0.05.

BW = body weight; LV = left ventricle; LVW:BW = left ventricle to body weight ratio; LVIDd = left ventricular internal diameter end-diastole; RWT = relative wall thickness; EF = ejection fraction; Circ = circumferential; sS = systolic strain; sSR = systolic strain rate; dSR-E = early diastolic strain rate; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean arterial pressure.

LV Fibrosis

Figure 4A illustrates representative photomicrographs of the young and aged LV stained with picrosirius red, which provides an estimate of fibrillar collagen deposition. Specifically, there was a significant increase in LV interstitial collagen staining (Figure 4B) in the aged hearts compared to the young hearts.

Figure 4.

Representative histological myocardial image at 40x objective magnification (A) and quantification of picrosirius red staining (B) of LV fibrosis between young and aged hearts. Values are mean ± SE. n=5 for both age groups. *P<0.05.

Discussion

This study, using an experimental Fischer rat model of aging, demonstrates that aging is associated with changes in the global coronary vasculature as documented by high resolution micro-CT imaging. Specifically when indexed to LV mass, the total and intramyocardial vessel volumes were significantly lower, while the epicardial vessel volumes, with and without indexing to LV mass, were significantly higher in the aged heart compared to the young heart. Furthermore the percentage of intramyocardial vessel volume that comprised the total vessel volume of the aged heart was significantly lower than the young heart. Importantly, this reduction in normalized intramyocardial vessel volume within the aged heart occurred in the setting of increased LV fibrosis and mild LV dysfunction.

In the current study we utilized high-resolution micro-CT imaging technology 18-21 to visualize the 3-D coronary vasculature and to quantify specific changes in the intramyocardial and epicardial vessels of varying luminal diameters in young and aged hearts. Notably, other studies have also reported the unique capabilities of this technology and analysis to detect changes in the architecture of the renal microvasculature as well.12, 15, 22 Typically, sequential sectioning of the heart and histomorphometric analysis has been the primary methodology used to assess and quantitate the coronary vasculature. 11, 23-26 While this conventional histopathological analysis has been considered the gold-standard for examining the coronary vasculature, this method is very labor intensive and only provides information on the coronary circulation in a very small percentage of the entire heart. Cardiac micro-CT technology goes beyond the capabilities of histomorphometric analysis because of its high resolution and image analysis capabilities which allows for the global evaluation of the organ vasculature, vessel size distribution patterns and connectivity. 13, 15, 18, 19, 27

Here using micro-CT imaging, we observed that the aged hearts had a significant increase in the total as well as epicardial vessel volumes as compared to the young heart, with no change in the intramyocardial vessel volume. Importantly, as LV mass increased with aging, the epicardial vessel volume significantly increased, whereas the intramyocardial vessel volume did not change. This increase in epicardial vessel volume may be explained by an increase in the number, total length and/or diameter of the epicardial vessels. Indeed it is tempting to speculate that this may be a programmed response to natural myocardial growth associated with aging in order to permit optimal delivery of oxygenated blood throughout the mature myocardium. However the biological mechanism by which the epicardial vessels increase with age remains to be defined. Nonetheless when indexed to LV mass, the aged heart was characterized by a significant decrease in the total as well as intramyocardial vessel volumes as compared to the young heart. Whereas the aged heart maintained a significantly higher epicardial vessel volume, when normalized to LV mass, as compared to the young heart. These observed changes suggest that the increase in epicardial vessels (per gram of LV mass) may, in part, be an adaptive response for the decrease in intramyocardial vessels (per gram of LV mass) in attempt to maintain adequate tissue perfusion and nutrient delivery. Furthermore, when normalized to the total vessel volume, the aged heart had a significantly lower percentage of intramyocardial vessel volume as compared to the young heart. Importantly, there was an inverse relationship between the decreased percentage of intramyocardial vessel volume and increased LV fibrosis in the aged heart. Furthermore, in association with this increase in LV fibrosis, systolic function as documented by LVEF as well as circumferential sS and sSR and diastolic function as documented by circumferential dSR-E were significantly reduced in the aged heart. The increase in LV fibrosis seen here is consistent with previous reports that demonstrated the collagen accumulation progressively increases with normal aging in both experimental animal models 3, 11, 28 and in humans. 1, 29

Cardiac fibrosis is a hallmark of aging and deposition of collagen in the myocardial interstitial space is associated with reductions in myocardial compliance and function as seen experimentally 3, 30 and in humans. 5, 31, 32 While advances have been made in our understanding of mechanisms that contribute to age-associated cardiac fibrosis, such as alterations in collagen turnover 9 and changes in BP, 10, 33 alterations in the coronary circulation with aging is not well defined. Although a decrease in coronary capillary density with aging has been previously reported by histomorphometric analysis, 11 the influence of age on the intramyocardial and epicardial vasculature of varying luminal diameters remains poorly defined, primarily due to the lack of sensitive imaging technology. The current study therefore provides new and additional insights into the evolution of age associated changes in the coronary vasculature as determined by high resolution micro-CT imaging.

Study Limitations

In this study we documented the coronary vasculature changes that occurred between young and aged hearts in coronary vessel volume ranging from 80 to 760 μm in luminal diameter, where intramyocardial vessels were defined as diameters from 80-360 μm and epicardial vessels were defined as diameters from 361-760 μm. Although the resolution of micro-CT can be as high as 1 μm voxels, limited computing power currently restricts routine handling and analysis of such enormous image files. Here we used 20 μm voxels, and an enhancement of less than two adjacent voxels was considered as noise so that analysis was restricted to coronary vessels ≥ 80 μm. Furthermore, future cardiac micro-CT aging studies are needed to investigate coronary arterial resistance vessels (<75-100 μm in diameter) and capillary density and their role in myocardial perfusion. In addition, it is also possible that the myocardial vasculature might have been misclassified due to residual vascular tone with a consequent decline in the diameter of epicardial vessels. However, we believe this was unlikely because our tissue preparation allowed for complete coronary vessel relaxation. 20

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the age related coronary vasculature changes in the total, intramyocardial and epicardial vessel volume using high resolution micro-CT imaging. These observations also have clinical implications, particularly in therapeutic strategies targeted at promoting angiogenesis with ultimate goal of preventing detrimental effects such as excessive fibrosis and preserving or improving cardiac function. Further, this technology not only underscores the utility of micro-CT imaging to gain important insights of the coronary vasculature during aging, but could also be useful to address other physiological and pathophysiological conditions and warrants further investigations.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

The aging heart is susceptible to structural and functional changes that increase the risk of heart failure, which continues to rise in our aging population. Although seminal advances have been made in our understanding of changes to the cardiomyocyte and extracellular matrix in aging as well as in disease, less has been made on global alterations of the coronary vasculature. Our study aimed to provide insights into age-associated changes in the coronary vasculature using high resolution micro-CT imaging technology. This technology gives us the ability to evaluate the entire coronary circulation, which we are unable to do with conventional histomorphometric techniques. In this study, using an experimental Fischer rat model of aging, we demonstrated important changes in the epicardial and intramyocardial coronary vessels, at varying arterial luminal diameters, between young and aged Fischer rats using micro-CT imaging. Specifically, in the setting of a growing myocardium due to aging, we observed the increase in epicardial coronary vessel volume while the intramyocardial coronary vessel volume was reduced. Hence, cardiac micro-CT technology represents a powerful imaging tool that provides a greater and more representative understanding of adaptive changes to the entire coronary circulation in aging and could also provide important insights into other pathological states as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the outstanding contributions of Jill L. Anderson, Andrew J. Vercnocke and David F. Hansen.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants RO1 HL36634, R01 HL83231, R01 EB000305 and PO1 HL76611 from the National Institute of Health and the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olivetti G, Melissari M, Capasso JM, Anversa P. Cardiomyopathy of the aging human heart. Myocyte loss and reactive cellular hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1991;68:1560–1568. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.6.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anversa P, Capasso JM. Cellular basis of aging in the mammalian heart. Scanning Microscopy. 1991;5:1065–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sangaralingham SJ, Huntley BK, Martin FL, McKie PM, Bellavia D, Ichiki T, Harders GE, Chen HH, Burnett JC., Jr The aging heart, myocardial fibrosis, and its relationship to circulating C-type natriuretic Peptide. Hypertension. 2011;57:201–207. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber KT, Brilla CG. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac interstitium. Fibrosis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Circulation. 1991;83:1849–1865. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part II: the aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107:346–354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048893.62841.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cieslik KA, Taffet GE, Carlson S, Hermosillo J, Trial J, Entman ML. Immune-inflammatory dysregulation modulates the incidence of progressive fibrosis and diastolic stiffness in the aging heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein M, Boulaksil M, Jansen JA, Herold E, Noorman M, Joles JA, van Veen TA, Houtman MJ, Engelen MA, Hauer RN, de Bakker JM, van Rijen HV. Reduction of fibrosis-related arrhythmias by chronic renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in an aged mouse model. Am J Phys. 2010;299:H310–321. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01137.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradshaw AD, Baicu CF, Rentz TJ, Van Laer AO, Bonnema DD, Zile MR. Age-dependent alterations in fibrillar collagen content and myocardial diastolic function: role of SPARC in post-synthetic procollagen processing. Am J Phys. 2010;298:H614–622. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00474.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varagic J, Susic D, Frohlich E. Heart, aging, and hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2001;16:336–341. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anversa P, Li P, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G. Effects of aging on quantitative structural properties of coronary vasculature and microvasculature in rats. Am J Phys. 1994;267:H1062–1073. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Sanz A, Rodriguez-Barbero A, Bentley MD, Ritman EL, Romero JC. Three-dimensional microcomputed tomography of renal vasculature in rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:440–444. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen SM, Demirkaya O, Ritman EL. Three-dimensional imaging of vasculature and parenchyma in intact rodent organs with X-ray micro-CT. Am J Phys. 1998;275:H1103–1114. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd DJ, Helmering J, Kaufman SA, Turk J, Silva M, Vasquez S, Weinstein D, Johnston B, Hale C, Veniant MM. A Volumetric Method for Quantifying Atherosclerosis in Mice by Using MicroCT: Comparison to En Face. PloS ONE. 2011;6:e18800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu XY, Daghini E, Chade AR, Napoli C, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Simvastatin prevents coronary microvascular remodeling in renovascular hypertensive pigs. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1209–1217. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldkamp LA, Davis LC, Kress JW. Practical cone-beam algorithm. J Opt Soc Am A. 1984;1:612–619. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robb RA, Hanson DP, Karwoski RA, Larson AG, Workman EL, Stacy MC. Analyze: a comprehensive, operator-interactive software package for multidimensional medical image display and analysis. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1989;13:433–454. doi: 10.1016/0895-6111(89)90285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohuchi H, Beighley PE, Dong Y, Zamir M, Ritman EL. Microvascular development in porcine right and left ventricular walls. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:676–680. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31805365a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman A, Ritman EL, Wilson SH, Best PJ, Lerman LO. Altered myocardial microvascular 3D architecture in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2000;102:2028–2030. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Zhu XY, Chade AR, Amores-Arriaga B, Caplice NM, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Functional and structural remodeling of the myocardial microvasculature in early experimental hypertension. Am J Phys. 2006;290:H978–984. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00538.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu XY, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Chade AR, Sica V, Napoli C, Caplice N, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant intervention attenuates myocardial neovascularization in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2004;109:2109–2115. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000125742.65841.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bentley MD, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman A, Sarafov MH, Romero JC, Pelaez LI, Grande JP, Ritman EL, Lerman LO. Enhanced renal cortical vascularization in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1056–1063. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anversa P, Capasso JM. Loss of intermediate-sized coronary arteries and capillary proliferation after left ventricular failure in rats. Am J Phys. 1991;260:H1552–1560. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomanek RJ, Aydelotte MR, Torry RJ. Remodeling of coronary vessels during aging in purebred beagles. Circ Res. 1991;69:1068–1074. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomanek RJ, Gisolfi CV, Bauer CA, Palmer PJ. Coronary vasodilator reserve, capillarity, and mitochondria in trained hypertensive rats. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:1179–1185. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.3.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomanek RJ, Palmer PJ, Peiffer GL, Schreiber KL, Eastham CL, Marcus ML. Morphometry of canine coronary arteries, arterioles, and capillaries during hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1986;58:38–46. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu XY, Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Cortical microvascular remodeling in the stenotic kidney: role of increased oxidative stress. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2004;24:1854–1859. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142443.52606.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakatta EG, Yin FC. Myocardial aging: functional alterations and related cellular mechanisms. Am J Phys. 1982;242:H927–941. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.6.H927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caspari PG, Newcomb M, Gibson K, Harris P. Collagen in the normal and hypertrophied human ventricle. Cardiovasc Res. 1977;11:554–558. doi: 10.1093/cvr/11.6.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee D, Sen S. Collagen phenotypes during development and regression of myocardial hypertrophy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1990;67:1474–1480. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.6.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Borlaug BA, Rodeheffer RJ, Kass DA. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community-based study. Circulation. 2005;112:2254–2262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Y, Yao Q, Zhu J, Luo B, Liang S. Age-related variation in the interstitial tissues of the cardiac conduction system; and autopsy study of 230 Han Chinese. Forensic Sci Int. 1999;104:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(99)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrmann J, Samee S, Chade A, Rodriguez Porcel M, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Differential effect of experimental hypertension and hypercholesterolemia on adventitial remodeling. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2005;25:447–453. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152606.34120.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.