Abstract

In this paper, we employ data drawn from economic and ethnographic interviews with Detroit heroin users, as well as other sources, to illustrate the relationship between heroin users’ mobility patterns and urban and suburban environments, especially in terms of drug acquisition and the geography of opportunity. We explore how the “spatial mismatch” (Kain 1968; 1992) between legal work opportunities and central city residents is seemingly reversed in the case of heroin users. We find that while both geographic location and social networks associated with segregation provide central city residents and African Americans with a strategic advantage over white suburbanites in locating and purchasing heroin easily and efficiently, this same segregation effectively focuses the negative externalities of heroin markets in central city neighborhoods. Finally, we consider how the heroin trade reflects and reproduces the segregated post-industrial landscape, and we discuss directions for potential future research on the relationship between ethnic and economic ghettos and regional drug markets.

Introduction

In addition to its other well-publicized troubles, Detroit, Michigan has long been haunted by associations with illicit drug use and crime (Boyle, 2007; Neill, 2001). Below the surface of the city’s bad image lies a historical trajectory driven by structural trends, a representative case for America’s broader urban crisis (Sugrue, 1996). Over time, Detroit’s metropolitan area has expanded into an ever-widening band of land, which now dwarfs the central city in terms of area, population and income (Darden et al., 1987; Kasarda et al., 1997). The ongoing “Great Recession” has intensified the impacts of these long-term trends, resulting in even higher levels of unemployment, home foreclosure and abandonment, especially in the central city and inner ring suburbs (Rugh & Massey, 2010). Detroit proper has now lost more than half of its peak population, and outmigration continues steadily to this day, as evidenced by the results of the 2010 Census (Linebaugh, 2011).

Detroit’s sprawling suburban region is also characterized by stark racial segregation, which has its roots in the restrictive racial enclaves and planning decisions of the 20th century (Roychoudhury & Goodman, 1996; Hill, 1980; Hill & Negry, 1987; Thomas, 1997). Detroit proper is more than eighty percent African-American, while in most of the surrounding suburbs the African American population is below ten percent. In the memorable words of Mike Davis (2002, p. 255), the metropolitan area is “Black in the deindustrialized center, lily-white on the job-rich rim.” The social divisions between these two adjoining realms are reflected in peoples’ mobility patterns—many suburban dwellers never venture into the city of Detroit at all, and when they do, they usually stick to controlled spaces, such as highways or downtown entertainment venues (Wilson & Wouters, 2003). For their part, many Detroit residents must go to the suburbs to work, shop, or attend schools, but they are constrained in multiple ways, most especially by real and perceived racial prejudice and lack of access to private transportation (Meiklejohn, 2002; Grengs, 2006; Allard, Tolman & Rosen, 2003). The structural separation of poor populations and accessible job opportunities has been termed “spatial mismatch” (Kain, 1968, 2004) and it is a defining characteristic many postindustrial American cities. However, while researchers have extensively examined the impact of segregated sprawl on access to jobs and social capital (Stoll, 2005; Kneebone, 2009), little has been written on geographical differences in access to illicit products and criminal opportunities.

In the early 1980s, Pettiway (1982, 1985) reported on the geographic selectivity of robbery and burglary offenders in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He found that ghetto residents were more likely to commit offenses in other ghetto neighborhoods than in non-ghetto areas, even though these areas were not as wealthy, simply because of physical and social convenience: “The constricting nature of the ghetto and the resulting short offense-residence distances suggest that black offenders travel much shorter distances than their white counterparts” (1982, p. 267). At the same time, he also reported that residents of non-ghetto areas only rarely ventured into ghetto areas to commit crimes. In a later publication, Pettiway (1985, p. 207) wrote of the dynamic “interactions with other elements in the urban matrix” that tended to produce specific patterns of both criminal and non-criminal behavior. Though Pettiway focused on select categories of property crime (robbery and burglary), it is reasonable to assume that similar factors might affect other illicit activities, such as heroin acquisition and use, as individuals respond in clearly patterned ways to a matrix of structures and relationships—including racial divisions--that define their everyday lives. To what extent does this racially segregated landscape shape patterns of heroin acquisition, use and risk? Conversely, we might ask how is the landscape itself shaped by these patterns?

In this paper, we explore these questions through an examination of the mobility and purchasing patterns of active heroin users residing in and around the city of Detroit. We integrate ethnographic interviews with economic questionnaires, as well as external sources such as local media and law enforcement reports, as we examine the relationship of heroin users’ mobility patterns to the segregated geography of Detroit. Through our analysis of these findings, we seek to connect to the larger landscape of the metropolitan region as it is reflected in the flow of this illicit commodity. We do this in three stages. First, we present background material on heroin markets and urban areas. Secondly, we offer a theoretical rationale for our methodological approach, which involves a blend of ethnographic and economic approaches to urban heroin use, and we explain the specific methods that were used, including the sampling procedure and its limitations. Third, we present findings from our ethnographic and economic investigation concerning patterns of heroin procurement and mobility across the urban-suburban divide. Specifically, we present evidence from ethnographic interviews conducted with active heroin users (n=30), conducted in Detroit, in combination with extensive surveys of economic behaviors that were collected from a larger sample (n=109). We then interpret these findings in the context of other research on substance use patterns in Detroit and other cities. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings for our understanding of post-industrial cities, the relationship between racial and spatial segregation and illicit substance use patterns, and potential future research.

Illicit Drugs and Urban Places

In popular discourse, illicit drugs such as heroin are often viewed biologically or morally, as aids to healing or as corrupting influences, or as demons that possess and ruin lives (Acker, 2001; Reinarman, 2005). Historians have taken a broader view, examining heroin use as it relates to American culture and politics (Musto, 1973); to the strains produced by the racial divisions and inequalities of urban environments (Schneider, 2008); and to modernity itself (Hickman, 2004). But drugs are also tangible physical commodities that command a price and actively mobilize buyers and sellers across multiple geographic scales (Pearson and Hobbs, 2001). Recreational and habit-forming drugs are material substances typically purchased for immediate use, which tends over time to stimulate repeat consumption and intense market demand (Murji, 2007; Caulkins, 1995; Riley 1997; Caulkins & Reuter, 1998; Reuter & Caulkins, 2004). While standard economic theory allows for addictive goods to be treated as any other consumptive commodity and therefore encourages policies that use the laws of supply and demand as the basis for analysis, an emerging subfield of economics calls for a more nuanced approach to modeling markets for illegal drugs (Caulkins & Reuter, 2004). Reuter and Haaga (1989) have attempted to summarize the literature concerning the market structure for illegal drugs, stating that market power is elusive (the drug market is clearly not a monopoly) and prices are highly variable by and within geographic locations.

Although drug deals and drug use take place in particular locales, these are not fixed, but are mutable and dynamic, dissolving and reassembling in response to fluctuations of supply and demand as well as environmental factors such as police action. According to Coomber (2007), drug markets are “dynamic, shifting, changing and diverse” (p. 750); Agar and Wilson (2002) likewise define heroin epidemics as “complex adaptive systems.” The blocks, neighborhoods, cities and regions where heroin markets occur are the stages on which we may see the interplay between local populations’ demand, sociospatial characteristics and global supplies (Agar & Schact Reisinger, 2001).

This is not a new insight. In his pioneering work on opium addiction in Chicago, Dai (1937) explored the relationship between neighborhood characteristics, social contexts and opiate use. Parker, Bakx and Newcombe (1988) documented the changes brought on by the growth of the heroin market and its integration into pre-existing working-class subcultures of North-West of England. Ruggiero and Vass (1992) have described the interrelationship between illicit heroin distribution networks and the licit economy in three Italian cities: Naples, Verona and Turin. They found that the heroin market was adapted and integrated into the pre-existing social and economic structure, to the point where the two became symbiotic. “The illicit and licit economies of a state,” they concluded, “learn to coexist and reciprocate with each other, and at some point such activities become ingrained in the social structure to the point where the boundaries which separate the two become blurred and negotiable” (p. 290). Likewise, Sullivan (1992) compared youth crime and employment patterns in three neighborhoods in Brooklyn, New York and found significant variation in the social relationships and contexts that surrounded drug-selling activities, in spite of similar levels of access to illicit drugs. Valdez and Cepeda (2008) have examined the connection between the formation of segregated Mexican enclaves in San Antonio, Texas and the development of heroin markets and local heroin practices, and Garcia (2010) has explored heroin addiction in relation to the landscape and the history of loss among the Spanish-speaking people of rural New Mexico, where heroin use is largely contained and transmitted within close familial relations. Draus and Carlson (2006, 2007) reported both parallels and significant variations between patterns of crack cocaine and heroin use in rural Ohio and those evident in the research literature.

As noted in our introduction, Detroit’s culture of illicit drug sales and use has been well documented in both popular (Adler, 1995; Jones, 2006) and scholarly (Mieczkowski, 1986, 1990) works. Tourigny (2001) has explored the impact of neoliberal welfare policies on the lives of poor families in Detroit, especially in regards to drug-dealing, and Bergmann (2008) drew connections between political and economic abandonment and the creative resistance of drug-dealing youth in the same city. In these studies, ethnography adds density or “placeness” to what otherwise might be a flat, abstract or statistical representation of social space (McLafferty, 2008). As these works illustrate, social sciences have become more sensitized to the importance of place in shaping human behaviors and relationships (Gieryn, 2000; McLafferty, 2008). Even very individualized measures such as self-efficacy have been found to vary with modest changes in neighborhood characteristics (Rosenbaum, Reynold & Deluca, 2002).

Economics has been more resistant to considerations of context, relying more on highly individualized rational choice models (Barnes, 1996). For example, in economists’ rational addiction models (Becker and Murphy, 1988; Chaloupka, 1991) individual differences in capital accumulation and depreciation and incentives, or learning and regret functions (Orphanides & Zervos, 1995) are emphasized. While the effects of these incentives may be described in abstract equations, the actual incentives are highly dependent on context, and may vary across time and space. In mathematical economic models these factors are often considered exogenous. However, in economic geography, Peck (1996) has called for more focus on the social characteristics of specific labor markets. Ghezzi and Mingione (2007) have likewise argued that empirical research should document the particularities of networks and locations in which market relations are inevitably enmeshed.

Methods and Sample

We draw on a sample of 109 economic inventories that were conducted with active heroin users. These inventories covered a broad range of areas, including daily income, both illegal and legal sources of income, amounts spent on heroin, other opiates or other drugs, as well as time and money spent in other activities. We also utilize data from in-depth qualitative interviews conducted among a smaller subsample of 30 individuals. Both the economic inventories and ethnographic interviews were gathered over a period of approximately two years, from 2006 through 2008. Participants were recruited on a volunteer basis after they had completed an initial telephone screening for two larger biobehavioral studies, both of which focused on drug-seeking behavior among active heroin users, conducted by Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, Michigan. These larger studies excluded applicants younger than 18 or older than 55. The investigators established 18 years as the lower end due to adulthood and ability to provide informed consent, and 55 years as set as the upper cutoff due to safety concerns related to (older) age-altered metabolic changes, because experimental drugs were administered to these participants. These criteria were therefore put in place primarily to limit potential risk to participants. They also excluded those who had current diagnosable mental illness (other than substance misuse itself) or serious medical issues, or were seeking drug abuse treatment. However, because psychiatric interviews were not conducted until the second screening visit for the biobehavioral study, participants in the smaller study described here were not necessarily affected. In any event, the data were not joined together, so we cannot state categorically that no individuals with a diagnosable mental illness were included.

It is very difficult to access and assess the size of hidden populations such as illicit drug users (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004), and we cannot accurately determine the age structure and racial, ethnic and gender composition of the Detroit heroin-dependent population. Therefore, the sample cannot be construed as representative of all heroin users. Nevertheless, we believe that the patterns of procurement and use evident in the sample are reflective of the regional heroin market as a whole. Likewise, the daily routines exercise that we employed, though intensely descriptive, was conducted to protect subject confidentiality above all else. Therefore, geographic address data were not collected, though we did ask how far individuals traveled each day, using what means of transportation. In some cases, however, individuals did identify specific areas, neighborhoods or intersections.

We complement our original economic survey data and ethnographic interviews with an array of other sources, drawn from newspapers and other media as well as academic journals, policy analysis think tanks and government agencies, in order to make connections and pose questions. We consider our participants’ reported patterns of heroin acquisition and use within the distinctive landscape of Detroit, shaped as it is by racial and spatial segregation, and the relationship of heroin markets to the larger geography of opportunity (Galster & Killen, 1995; Rosenbaum, Reynolds & Deluca, 2002; Briggs, 2005), specifically the issue of spatial mismatch (Kain, 1968, 1992, 2004; Gobillion, Selod & Zenou, 2007; Stoll, 2005). By placing our findings concerning heroin users’ mobility strategies (Clifton, 2004) within the distinctive context of the Detroit metropolitan region, we seek to draw connections between multiple layers of the city, emphasizing the interplay of local contingencies and places with flows of heroin through urban space more generally. These, in turn, may lead to new directions of research on Detroit and other de-industrialized cities with thriving drug markets.

Findings: Heroin Circulations

In the selections from ethnographic interviews included below, the study participants are each identified by a three-digit number, with some basic demographic descriptors. Quotations are largely kept intact to preserve the context of the interaction between participants and the interviewer (first author). The voice of the interviewer is identified by italics. In the interviews, participants were asked to outline their daily routines in terms of the places that they went and the people they interacted with on a typical day—their active social networks. They were given cards labeled simply “Place 1,” “Place 2,” and asked to group them with other cards that were labeled “Person 2, Person 3, Person 4”, and so on (Person 1 was the individual, or ego, at the center of the network). Sometimes participants adopted this terminology into their responses. For example, a white suburban-dwelling male, 29 years old (003), described his routine this way:

Place 1 would be my house and my mom lives with me so I interact with her every morning like clockwork. And then on a day I would use this is how it would work.

Place 2 would be the gas station at the corner of my street and the two people that work there are there every single day like clockwork and they say the same thing to me every day.

And then after that I go directly to Place 3 – a dealer – in the [states an intersection located on the outer edge of the city, near the northern suburbs and a major expressway] area and if they’re not there early in morning, which they sometimes aren’t, I would go about a mile away, the same area, to Place 4 which isn’t preferred because it’s the same price but what they have is typically smaller and I kind of feel like I’m getting ripped off. But it’s about the same.

This individual worked alone, as a self-employed handyman and house painter, so his schedule could be effectively wrapped around his heroin acquisition and heroin use. He might repeat this pattern two or three times in a given day, depending on how much money he was able to earn. This contrasted significantly with the schedule described by a 47-year-old African-American man (014) who lived in the central city (also sharing a home with his mother):

I wake up, and I’m on the phone. I make the call, I get up, go upstairs to see if mom’s made it through the night, you know, sit up in the kitchen for a minute, then I stay downstairs. Turn the TV on, this is a daily routine, I sit there and I turn the TV on and I watch the news, like I said between that phone call and 7:30 that car pulls up, and it’s very rare that he might tell me, I’m out [of heroin] right now, 20 minutes or something like that, very rare.

Each of these individuals purchased heroin an equal number of times (21) during the week. In the economic interviews, the second man claimed to spend 25 minutes, traveling 0 miles, while the first man claimed to spend only 5 minutes, traveling 0.5 miles. This is a case where the details provided in the ethnographic interviews allow us to infer that the first man is probably underestimating his travel time and distance, because we know that his stated purchase site is located about 2 miles from the suburban border (although close to an expressway, which might reduce travel times) while the second man is counting the time waiting for his heroin dealer to arrive. Strictly speaking, the second man is not spending any time traveling, only time waiting.

In other cases, commuting users used public transportation to make the journey to their heroin source. A 48 year-old white man (007), described his routine, which varied depending on whether he used public and private transportation:

Sometimes I get a ride or I go to the bus, and I take the bus to my connection.

Ok. Ok so let’s say you go to the bus, you catch the bus?

Yeah I catch the bus half the time.

Ok and other times you would…

Um, ride with a friend or my nephew will let me use his van….And ya know, and sometimes I get mine for free, ya know.

Sometimes you get your uh…

…heroin for free. If somebody needs a ride…

Oh ok. Because you have the van…

Right, they pay me.

Because you have the van.

Right, they pay me to take them.

In his economic interview, he estimated that he traveled 3 miles, that it took him 30 minutes to do so, and that he purchased heroin 5 times a week.

A 52-year-old African American man (008) described a much different routine, involving more purchases per week (14) but less time and distance per journey. He would begin by driving himself to his heroin source:

It’s not a house, it’s a corner.

How many people do you see there?

I see one person who I’m getting the drugs from but it could be 10 or 15 people on the corner.

So the one person you see every day would be that one person.

That one person at the corner, yeah.

And how long would you be there?

About 15 [minutes], half hour, hour, stand there and talk, bull-shit.

He reported purchasing heroin 14 times a week, although he also stated that his pattern might vary from day to day in its particularities. However, he almost always remained in the same bounded area:

It doesn’t go the same every day, it varies. Whatever I wanna do the rest of the day it changes. I might do some work somewhere, or… you know it doesn’t be the same every day after that. It varies. Whatever I can do, if I got some work, some people need me to rake leaves or cut grass or whatever I can do to make a dollar in my pocket. That’s what I do at that time.

Ok so you go out, go back out, find out…

Find out what I can do to make some money.

This be around the neighborhood or something?

Yeah, around the neighborhood, or, anywhere else I try to make a dollar. It can be… I can go on the west side, see what I can do on the west side. Anything I can do to make a dollar.

So most days you stay in the neighborhood or most days you go out?

Most days I stay in the neighborhood.

The descriptions contained in these accounts reflect patterns of purchasing that are evident in the larger economic sample. Results based on the entire economic sample and a full analysis of the relationship between income, purchasing habits and other variables have been reported separately (Roddy, Steinmiller & Greenwald, 2011). Among the total of 109 users, regression analysis revealed that weekly purchasing was inversely associated with time spent during purchase and positive associated with monthly income and number of suppliers (p< .05). In contrast, daily heroin consumption (bags used per day), percentage of income spent on heroin and unit purchase amount (i.e. dollars spent on heroin during one purchasing episode) were not significant predictors in the regression. Thus, availability factors proved to be more influential in the larger sample than other potential determinants. For these three particular users (014, 007, and 008) purchases per week are reported as 21, 5 and 14 while monthly income is reported as $1120, $810, and $1210. These data are inconsistent with the hypothesis that a purposeful strategy by those who have access to more income is to buy larger amounts of heroin less frequently, unless of course, that income is obtained in small but frequent increments.

Another African American man, age 51 (012), would typically stay up until 6 a.m. and then sleep until 2 p.m. He would go to “cop” his heroin around 2:30 p.m. This is how he described his routine:

So is there a regular place that you go every single day for that?

Yeah.

Is it a house?

Yep.

Are there people there that you see every single day?

Yeah, the guy I get it from, yeah.

Ok so just the one guy?

No, it’s two or three guys in there that I get it from.

Ok you know them, I mean, you see them…?

I see ‘em, they be there, yeah.

Ok. So these are all seller guys, dealers?

Yeah, and users too, yeah.

Now are these… how old are these guys? These are all men?

Yeah. I don’t know, I don’t know.

Like 20’s, 30’s?

One of ‘em is an old cat, he’s older than me. I don’t know, he’s probably 60-something years old and the other two I think are nephews or some shit, they young guys in their 20’s.

They all African American?

All African American.

Ok so how long have you been knowing these guys?

Two and a half months now.

So are they all in the same neighborhood?

Yeah, not too far from my house.

Ok so to get from your girl’s place to their house, it’s just a couple minutes, or…?

About 10 minutes walk.

Ok. So you’d say you’d be there maybe from…?

I’m just in and out, I don’t stay there, I don’t use there, I just [buy] there.

Ok so you just buy there and then you move on.

Yeah. Go home and use…

Ok so how long are you back at the house then?

Hours, I be there. I be there for a while. Till maybe I don’t know, maybe 5:30 or so, then I go down the street. There’s a church down the street that feeds every day. You have to be there by 6:00, you gotta go through a hour church service, after service it be seven and they start feeding. But I usually go down there get me something to eat, do that.

As with many of the African Americans in the sample, there is a high degree of geographic concentration evident here. Money is often earned through a combination of legal and illegal activities and food and shelter are obtained locally through social networks and charitable sources. He described these activities this way:

Sell a little dope if I can, hustling, stealing, meddle up houses, just petty little stuff now because I can’t stand to go back to prison anymore. I’m getting too old, they gonna keep me a long time, I know that, if I go back, so I try to keep it as minimal as I can, just really petty things, stealing stuff off of houses, looking inside, you know hustling, anything, anything like that.

These “hustles” arise through a combination of planning and spontaneity that is driven by both addiction and economics, and actively shaped by multiple “elements in the urban matrix” (Pettiway, 1985). In his words,

When I wake up, I usually try to have that [money for heroin] the night before. But if I don’t have it, then I have to hustle. I need to have something planned, I have to plan something, every day for the next day. Just ongoing, it’s a habit, I got that habit, so I’m in for that. I’m living to use, it’s crazy, but it amazes me too, how I gets it sometimes, all the time, it’s crazy, I be amazed.

For a 26-year-old white woman (026), living in a near suburb of Detroit, the routine is just as regular, though the ground covered is greater and the means of obtaining income are less varied—she had some savings from a job as a steelworker, and she also borrowed money from her family. She reports driving, with her boyfriend, to an apartment building in Detroit, where she buys heroin from a rotating group of African-American men:

So do you go inside at all or is it a matter of…?

Yeah, sometimes. Sometimes go inside or they could I don’t know meet us at the store or something. It all depends. In that case they would get in the car with us.

So they’d actually get in the car and go to the store or…?

Or like uh we’ll be sitting up at the store waiting and [they] like walk up there and get in the car.

And so I mean, how long would the trip so it’s it’s but you say it’s about a takes you does you take it an hour to get there or…?

‘Bout half an hour.

Okay. So then after you leave there, by eleven thirty let’s say, and where then where would you go?

Um. Usually back home.

What about um so you go back to your parent’s house?

Yeah.

Now what about where would you where would you go to actually use?

My bedroom. Or on the way home actually what we’ll we’ll first get we’ll we’ll use right away. In that case, uh actually we just pull around the side of the road somewhere.

Okay. so then you go back home you’re home by around what time? By noon or?

Yeah.

And then how long would you stay there?

Probably for a few hours. Most of the time it’s lately my life has been just about this is it. Just going out and getting high and coming home.

An African-American woman in her late forties (029) had a daily routine which illustrated both sides of the spatial mismatch. She lived in Detroit, in a vacant house that she squatted in with a male friend. She caught a bus at 4:15 a.m. to go to work, usually at suburban job sites that were contracted through a day labor service located about eight miles north of the city:

You know the jobs are usually you know six [a.m.] to two thirty, seven to three thirty, eight to four thirty, you know. That’s, that’s generally it.

She made these long daily journeys to earn a modest daily wage hanging Christmas lights in suburban downtowns (this interview was conducted in mid-December). However, she only had to make a brief walk from the bus stop in Detroit to buy her daily heroin.

Yeah. So and like I said down [names a particular intersection], in that square area I can walk to someone that I personally know…I get off the bus right there…I got to walk three blocks.

This pattern was unusual in our sample, simply because most African-Americans did not leave the city of Detroit on a daily basis, if they left it at all. As we have seen, some remained in their own neighborhoods. However, it vividly reveals the larger landscape that surrounds the mobility patterns of both heroin use and work. In the next section, we consider these mobility patterns, as revealed by both ethnographic and economic data, in relation to the larger regional context.

Heroin and the Urban-Suburban Divide

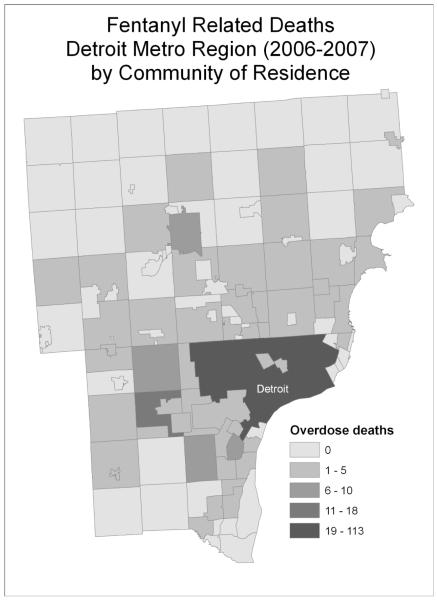

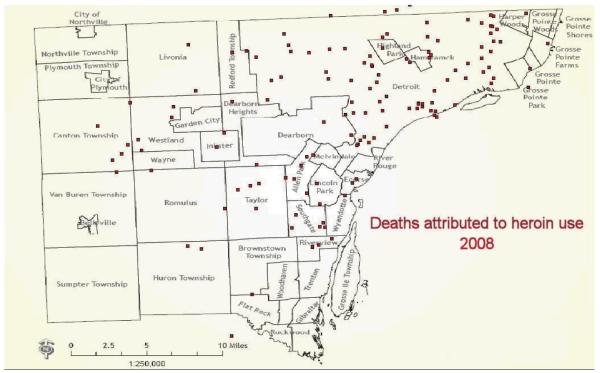

In recent years, there has been a reported resurgence of heroin use in the US, especially among younger suburban and rural whites (Draus & Carlson, 2006; Jones, 2008; Archibold, 2009). This trend received national attention in 2006-2007 as a result of a string of overdose deaths linked to heroin that was mixed with the powerful synthetic opiate fentanyl. More than 1,000 people died nationwide as a result of the fentanyl mixture, and more than 300 of these were from the Detroit region (Schaefer & Swickard, 2007). The outbreak was significant not only in and of itself, but because it threw the sociology of the heroin market into sharp relief. The victims all obtained their fatal doses from sources in the city, yet their places of residence were scattered throughout the metro region. The deaths cut across many segments of the highly segregated urban and suburban landscape (Schaefer & Swickard, 2007), illustrating the social linkages fostered by the drug market (see Figure 1). Though the fentanyl outbreak suggested that about half of regular heroin users came from outside the city, a map created by the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office (Polverento & Schmidt, 2009, see Figure 2) revealed another striking reality: the places of death related to heroin use were highly concentrated inside the city, and often within close proximity of each other.

FIGURE 1.

Data Source: The Detroit Free Press, map created by Jacob Napieralski

FIGURE 2. Deaths attributed to heroin use, Wayne County, Michigan, 2008.

Source: Gerry Polverento and Carl Schmidt, Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office

A presentation by the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office (2009) to the Detroit-Wayne County Drug Surveillance Group, formed in the wake of the fentanyl outbreak, revealed the geographic regularities of heroin markets in the city of Detroit that are well known to law enforcement agencies. After reporting the continuing trend of younger, white, suburban-based heroin users migrating to Detroit to purchase heroin on a daily basis, one of the presenting officers drew a conceptual map of the city in which he outlined the areas where arrests of commuting addicts were most frequent. These included the long borders between Detroit and its northern suburbs, which are characterized by multiple major thoroughfares and numerous exit routes. The same officer observed that heroin users who resided within central cities were more likely to purchase their heroin locally.

This geographic awareness has also informed social control efforts. For example, law enforcement agencies have targeted the bus routes that commuting addicts are most likely to employ, resulting in arrests of 70 individuals within a single week in 2009 (ClickOnDetroit.com, 2009). These users had reportedly turned to riding buses in larger numbers because the police had begun aggressively impounding vehicles. In other cases, police specifically target those who commute by automobile, impounding the vehicles of those suspected of purchasing heroin in city neighborhoods. Significantly, these tactics differ from those employed against heroin sellers, who are often arrested and incarcerated through “buy and bust” activities, in which undercover police officers pose as purchasers. All of these tactics may work to effectively suppress activity within a targeted area for a period of time. Nonetheless, given the porous nature of the urban-suburban boundaries, the power of heroin addiction, and the economic incentives to continue operating markets within distressed communities, the flow of bodies, drugs and money are unlikely to abate.

The pattern of addicted individuals who reside in less deprived areas obtaining their supplies of illegal drugs in more deprived areas has been observed in studies from Glasgow (Forsyth et al., 1992) to Ohio (Draus et al., 2005; Draus & Carlson, 2006). Though many studies have focused on the integration of illicit drug markets into the economies of particular “distressed” or “deprived” neighborhoods most affected (Sullivan, 1989; Fagan, 1992; Ensminger, Anthony & McCord, 1997; Murji, 2007) fewer have attempted to look at patterns of illegal drug use and distribution in relation to the economies of whole regions. One exception, as described above, is Ruggiero and Vass’s (1992) research on heroin use and its relationship to the formal economy in three different Italian cities. The Detroit metropolitan region displays some characteristics of all three cities described by Ruggiero and Vass, a fact that reflects the extremely segregated geography of the city, along both economic and racial or ethnic lines. The white, suburban users that we interviewed occupy an environment much more like that of Turin, where illicit drug economies exist in the shadow of licit employment, especially in manufacturing, while the African-American Detroit residents live in a world more like that of Naples, where underground and criminal networks touch on almost every aspect of neighborhood life. Meanwhile, other suburban users find their way to heroin through recreational or pharmaceutical drug use, and only later become enmeshed in the urban environments where heroin markets are based. These users are more like those of Verona, though crossing into Naples every morning and evening. Like the Swedish heroin users described by Lalander (2003), they effectively “drift” into addiction, though they may become just as effectively stuck in its grip.

The spatial mismatch problem, as we have discussed, pertains to significant disparities in access to resources, networks, and opportunities that tend to correlate with both race and place of residence, especially in aging industrial cities defined by a legacy of segregation. Whites are advantaged overall, both by the relative stability and affluence of the communities where they reside, and by their more convenient access to resources and opportunities. Conversely, and somewhat perversely, both geographic location and social networks provide central city residents and African Americans with a strategic advantage over white suburbanites in locating and purchasing heroin easily and efficiently. Tables 1 and 2 (see below) illustrate some of the recurring patterns that reflect racial and spatial differences in terms of accessing heroin. Data are included from both the smaller ethnographic sample (n=30) and the larger economic sample (n=109). The larger sample provides a better index of the overall differences in the mobility patterns adopted by whites as opposed to African Americans, with whites traveling further, spending more time, and making fewer purchases per week.

Table 1. Racial Differences With Time, Distance and Mode of Travel (African Americans), Ethnographic and Economic Samples.

A=African American, W=White, B=Bi-racial

SD=Self Drive, FD=Friend Drove, WB= Walk/Bike, D=Delivered

| # | Age | Race | Gender | Travel Mode |

Travel Distance (miles) |

Travel Time (min) |

# of Purchases /Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 002 | 53 | A | M | SD | 4 | 8 | 14 |

| 005 | 53 | A | M | WB | 0.5 | 10 | 17.5 |

| 006 | 54 | A | M | WB | 0.5 | 10 | 10 |

| 008 | 52 | A | M | SD | 1.3 | 5 | 14 |

| 010 | 50 | A | M | WB | 0.5 | 25 | 5 |

| 011 | 46 | A | F | SD | 0.5 | 5 | 14 |

| 012 | 51 | A | M | FD | 0.5 | 0 | 21 |

| 013 | 49 | A | M | SD | 10 | 60 | 21 |

| 014 | 47 | A | M | D | 0 | 25 | 21 |

| 015 | 36 | A | F | SD | 10 | 60 | 14 |

| 016 | 49 | A | M | D | 0 | 25 | 14 |

| 018 | 52 | A | F | FD | 4 | 120 | 14 |

| 019 | 40 | A | M | WB | 0.5 | 6 | 21 |

| 024 | 48 | A | M | WB/D | 0.5 | 10 | 14 |

| 025 | 49 | A | M | WB | 0.3 | 60 | 7 |

| 029 | 43 | A | F | D | 2 | 30 | 14 |

| 009 | 29 | B | M | WB/FD | 1 | 17.5 | 21 |

|

Data

Mean (17) |

47.1 |

7 by car

7 WB |

2.1 | 28.0 | 15.1 | ||

|

Sample

Mean (109) |

48.7 | 1.8 | 31.2 | 15.0 |

Table 2. Racial Differences With Time, Distance and Mode of Travel (Whites), Ethnographic and Economic Samples.

A=African American, W=White, B=Bi-racial

SD=Self Drive, FD=Friend Drove, WB= Walk/Bike, D=Delivered

| # | Age | Race | Gender | Travel Mode |

Travel Distance (miles) |

Travel Time (min) |

# of Purchases /Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | 30 | W | M | SD | 3 | 20 | 14 |

| 003 | 29 | W | M | FD | 0.5 | 5 | 21 |

| 007 | 48 | W | M | SD | 3 | 30 | 5 |

| 017 | 48 | W | M | D | 1 | 15 | 14 |

| 020 | 48 | W | M | D | 5 | 17.5 | 21 |

| 021 | 44 | W | F | WB | 0.5 | 15 | 28 |

| 022 | 40 | W | M | SD | 5 | 30 | 10 |

| 023 | 54 | W | M | WB/RB | 4 | 60 | 12 |

| 026 | 26 | W | F | SD | 30 | 30 | 14 |

| 027 | 55 | W | F | D | 15 | 15 | 10 |

| 028 | 26 | W | F | SD | 8 | 45 | 14 |

|

Data

Mean (11) |

40.7 | 6 by car | 6.8 | 25.7 | 14.8 | ||

|

Sample

Mean (109) |

40.2 | 6.6 | 50.32 | 12.7 |

While this finding may seem intuitive, as critical researchers we must ask why this is so. After all, other profitable commodity markets involving in poor, urban neighborhoods are not uniformly dominated by neighborhood residents themselves; nor do they serve consumers from across an entire metropolitan area, as heroin markets do. Corner liquor stores, for example, cater almost exclusively to local residents. This thorough dominance of a regional illicit market would seem to be a potential source of economic and social power for inner city communities. Unfortunately, it does not seem to translate into capital accumulation or other forms of investment in those communities. While little research has been done on those who occupy the higher levels of the drug-trafficking hierarchy, what evidence there is suggests that those who make large profits from the drug trade are just as likely to locate in wealthier areas, insulated from the daily chaos of the street economy (Adler, 1985; Adler, 1995; Desroches, 2007). In other words, upper-level dealers are also living in the suburbs, and likely spending much of their money there as well. Ironically, the only legal taxes paid on drug-derived wealth from inner-city markets may also be contributing to suburban coffers. However, the brunt of the damage done by illicit markets—their negative externalities—are largely borne by central city neighborhoods.

Conclusion and Future Directions for Research

The spatial mismatch hypothesis (Kain, 1968, 1992, 2004) contends that the persistent poverty of urban African Americans specifically derives from their spatial and social segregation, because of the distance from available job opportunities and the inefficiencies in accessing those opportunities due to lack of access to transportation, educational and cultural barriers, and limited social networks (Meiklejohn, 2002, Grengs, 2006; Johnson, 2006; Stoll, 2005). In our interviews with active heroin users concerning their daily routines, one emergent pattern was the difference between the modes of travel and time expended locating and purchasing heroin, which seemed to correlate with both racial identification and place of residence. In brief, the pattern of suburban white users, who spent more time and money locating and purchasing heroin than African American users, seemed to mirror the classic situation of “spatial mismatch” that has been associated with African American central city residents. While African American central city residents traveled much shorter distances to purchase heroin, white heroin users in this sample were clearly not deterred by the ghetto’s “barrier effect” (Pettiway, 1982, p. 266), purchasing their heroin almost exclusively from African-American dealers within the city of Detroit, and sometimes traveling quite extensively to do so.

Heroin, of course, is a habit-forming drug, which entails long-term commitment on the part of its users; they are nothing if not a stable clientele. The average length of use in our sample was nearly twenty years. Heroin misuse, therefore, takes a substantial toll in both diverted and directed energy on a yearly and cumulative basis. Though heroin itself does not discriminate and its effects are widespread, the heroin trade, as an organized subculture and sub-economy, is a good deal more selective, reflecting long-term patterns of racial and spatial segregation (Cooper et al., 2008). Structural forces may actively conspire to maintain landscapes of inequality in multiple ways (Swyngedouw & Heynen 2003). As Aalbers (2006) has argued concerning Rotterdam, the processes of urban decline and the establishment of local illicit economies are symbiotic and mutually reinforcing. Paradoxically, increased intensity on the part of law enforcement may also lower the prices of illicit drugs, thereby increasing access within the low-income communities where local drug markets are based (Caulkins, Reuter & Taylor, 2006). We can thus imagine that the inequalities embedded in the post-industrial geography actively reproduce each other, as licit and illicit resources and opportunities flow in opposite directions and further entrench the perceptions of “suburb” and “inner city” as antithetical environments (Wacquant, 1993,1996, 2001; Peck & Theodore, 2008).

We propose that, in the case of Detroit, well-developed heroin markets serve as useful indices of the societal chasms that dominate postindustrial urban landscapes, much as Bourgois (2003) has argued concerning the political economy of crack cocaine in New York City and the geography of homeless heroin users in Los Angeles (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009). The intensity of ghettoization (Zukin 1998; Chaddha & Wilson, 2008; Gans, 2008) may be one important corollary of the entrenchment and operation of such markets. Both criminal behavior and the perpetuation of racial segregation may be conceived as dynamic interactions of individuals with these already segregated environments (Pettiway, 1982, 1985; Yin, 2009). Neighborhood disadvantage and disorder, as research has repeatedly shown, generate effects that worsen the mental health of residents, making substance abuse more likely (Ensminger, Anthony & McCord, 1997; Nikelly, 2001; Boardman et al., 2001). In each case, the ghettoized geography may be seen as both cause and effect of exogenous phenomena.

Heroin users are daily navigators of this post-industrial, wreckage-strewn landscape. Many denizens of central cities are clearly geographically constrained, and deprived of both physical and social mobility in the larger society (Gough, Eisenschitz & McCulloch, 2006; Clear, 2007; Draus, Roddy & Greenwald, 2010). Others, such as homeless individuals, drug users and dealers, scrappers, and sex workers, may seem to move about unfettered by routine or regulation in the urban underground economy (Brand-Williams, 2008; Hocking, 2005; Kasarda, 1992; Templin, 1995; Castells & Portes 1989). The illegal drug market or “game” epitomizes the illusory mobility of those existing on the urban margins-- making money quickly, creating hierarchies of achievement outside of dominant institutions, achieving local fame and influence through outlaw activity, often in very short periods of time (Mieczkowski, 1986, 1990; Bergmann, 2008). Nevertheless, this “game” often results in incarceration, which has long-term social and economic consequences of its own (Western 2006; Clear 2007).

Research on Detroit has emphasized the confluence of segregation, deindustrialization, decentralization, and state devolution—trends that have decimated Midwestern industrial cities in general and the Motor City in particular (Wilson, 2006; Reese, 2006; Draus, 2009). As Cox (2011) has suggested, the particular geographical formations of race, class, unemployment and opportunity cannot be considered apart from the larger landscape of American ideology and social policy. While abundant existing research supports the position that high levels of substance misuse and addiction are indicators of social exclusion and deprivation (Parker, Bakx & Newcombe, 1988; Fagan, 1992; Ensminger, Anthony, & McCord, 1997; Foster, 2000), it remains to be seen whether deliberate or efforts at altering that landscape--improving urban living conditions more generally (Freudenberg et al., 2005), building social inclusion at different scales (Smith, Bellaby & Lindsay, 2010), or redirecting metropolitan drug policy at broader social welfare, rather than control and enforcement (Kubler & Walti, 2001)--might mitigate either the causes or the effects of heroin use, in terms of overdose deaths, economic marginality, or associated criminal activities. Comparative research on cities or regions with markedly different histories and patterns of racial and spatial segregation, such as those of Latin America (Arias 2006; Sabatini & Salcedo 2011) might help to elucidate the relationship between ethnic or class-based ghettos and heroin distribution patterns, and illicit drug markets more generally. Likewise, attention should be paid to ongoing changes in urban segregation patterns, both in the US and internationally, as a factor in drug use and drug market patterns.

Given the current state of the US economy, it is unlikely that any sweeping efforts to reconstruct cities will emanate from the federal government, much less cash-starved state or local governments. The forces arrayed against urban communities are intense and growing. Local residents, institutions and organizations will need to improvise solutions on their own, although as Fairbanks (2009) has argued, such efforts may simply reproduce the geographic of inequality while diffusing governmental control. One might imagine law enforcement or legal system dollars being plowed into restorative justice programs that benefit communities most affected by addiction, rather than channeling them into expensive and socially destructive correctional systems (Clear 2007). More research needs to be done on these local efforts, and more attention paid to those which offer some promise of success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH R01 DA015462) and internal funding from the University of Michigan-Dearborn supported this research study. The views of the authors do not necessarily represent those of the funding agencies. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Jacob Napieralski in constructing the map used in Figure 2 based on data gathered by the Detroit Free Press. We would also like to thank Gerry Polverento for permission to use his map of homicides and drug-related deaths in Detroit.

Contributor Information

Paul Draus, Associate Professor of Sociology, Department of Behavioral Sciences, The University of Michigan-Dearborn, 4901 Evergreen Rd., Dearborn, MI 48128.

Juliette Roddy, The University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Mark Greenwald, Wayne State University School of Medicine.

WORKS CITED

- Aalbers MB. When the Banks Withdraw, Slum Landlords Take Over’: The Structuration of Neighbourhood Decline through Redlining, Drug Dealing, Speculation and Immigrant Exploitation. Urban Studies. 2006;43:1061–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Acker CJ. Creating the American Junkie: Addiction Research in the Classic Era of Narcotic Control. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adler PA. Wheeling and dealing: An ethnography of an upper-level drug dealing and smuggling community. Columbia University Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Adler WM. Land of Opportunity: One Family’s Quest for the American Dream in the Age of Crack. Atlantic Monthly Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Agar M, Schact Reisinger H. Open Marginality: Heroin Epidemics in Different Groups. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31(3):729–746. [Google Scholar]

- Agar M, Wilson D. Drugmart: Heroin Epidemics as Complex Adaptive Systems. Complexity. 2002;7(5):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Allard S, Tolman RM, Rosen D. The Geography of Need: Spatial Distribution of Barriers to Employment in Metropolitan Detroit. The Policy Studies Journal. 2003;31(3):293–307. [Google Scholar]

- Archibold RC. In Heartland Death, Traces of Heroin’s Spread. The New York Times; May 31, 2009. retrieved 8/26/2009 at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/31/us/31border.html?pagewanted=all. [Google Scholar]

- Arias ED. Drugs and Democracy in Rio De Janeiro: trafficking, social networks and public insecurity. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TJ. Logics of Dislocation: Models, Metaphors and Meanings of Economic Space. Guilford Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Murphy K. A Theory of Rational Addiction. Journal of Political Economy. 1988;96:675–700. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann L. Getting Ghost: Two Young Lives and the Struggle for the Soul of an American City. The New Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Stress and Drug Use Among Adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(2):151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle KB. The Fire Last Time: 40 Years Later, the Urban Crisis Still Smolders. The Washington Post. 2007 Jul 29; [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. Crack and the political economy of social suffering. Addiction Research & Theory. 2003;11(1):31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Schonberg J. Righteous Dope Fiend. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams O. Metal Thefts Plague Region. The Detroit News; Jul 8, 2008. retrieved 4/18/09, http://www.detnews.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080724/METRO/807240374/1409/metro. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs X. More Pluribus, Less Unum? The Changing Geography of Race and Opportunity. In: Briggs X, editor. The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America. Brookings Institution Press; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Castells M, Portes A. World Underneath: The Origins, Dynamics and Effects of the Informal Economy. In: Portes A, Castells M, Benton LE, editors. The Informal Economy. The Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1989. pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins J. Domestic Geographic Variation in Illicit Drug Prices. The Journal of Urban Economics. 1995;37(l):38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins J, Reuter P. What Can We Learn from Drug Prices? Journal of Drug Issues. 1998;28(3):593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins J, Reuter P, Taylor L. Can Supply Restrictions Lower Price? Violence, Drug Dealing and Positional Advantage. Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy 5.1. 2006 doi: 10.2202/1538-0645.1482. Article 3. Available at: http://www.bepress.com/bejeap/contributions/vol5/iss1/art3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chaddha A, Wilson WJ. Reconsidering the ‘Ghetto. City & Community. 2008;7(4):384–388. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka F. Rational Addictive Behavior and Cigarette Smoking. Journal of Political Economy. 1991;99:722–42. [Google Scholar]

- Clear TR. Imprisoning Communities: How Mass Incarceration Makes Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Worse. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Police Reveal “Heroin Express. 2009 Dec 4; ClickOnDetroit.com. < http://www.clickondetroit.com/news/21865485/detail.html>.

- Clifton KJ. Mobility Strategies and Food Shopping for Low-Income Families. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2004;23:402–413. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LF, Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Friedman R. Residential Segregation and the Prevalence of Injection Drug Use among Black Adult Residents of US Metropolitan Areas. In: Thomas YF, et al., editors. Geography and Drug Addiction. Springer Science; New York: 2008. pp. 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Cox KR. Commentary: From the New Urban Politics to the “New” Metropolitan Politics. Urban Studies. 2011;48.12:2661–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Coomber R. Introduction to the Special Issue. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37.4:749–754. [Google Scholar]

- Dai B. Opium Addiction in Chicago. Patterson Smith; Montclair, NJ: 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Darden JT, Hill RC, Thomas J, Thomas R. Detroit: Race and Uneven Development. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Dead Cities And Other Tales. The New Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Desroches F. Research on Upper Level Drug Trafficking: A Review. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37(4):827–844. [Google Scholar]

- Draus P. Substance Abuse and Slow Motion Disasters: the Case of Detroit. The Sociological Quarterly. 2009;50(1):360–382. [Google Scholar]

- Draus P, Carlson RG. Change in the Scenery An Ethnographic Exploration of Crack Cocaine Use in Rural Ohio. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6(1):81–107. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus P, Carlson RG. Needles in the haystacks: The social context of initiation to heroin injection in rural Ohio. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41(8):1111–1124. doi: 10.1080/10826080500411577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus PJ, Roddy J, Greenwald M. A hell of a life: addiction and marginality in post-industrial Detroit. Social & Cultural Geography. 2010;11(7):663–680. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2010.508564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus P, Siegal HA, Carlson RG, Falck RS, Wang J. Cracking the cornfields: recruiting illicit stimulant drug users in rural Ohio. The Sociological Quarterly. 2005;46:165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Anthony JC, McCord J. The inner city and drug use: initial findings from an epidemiological study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;48:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Drug Selling and Licit Income in Distressed Neighborhoods: The Economic Lives of Street-Level Drug Users and Dealers. In: Harrell AV, Peterson GE, editors. Drugs, Crime and Social Isolation: Barriers to Urban Opportunity. The Urban Institute Press; Washington, D.C.: 1992. pp. 44–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks RP. How It Works: Recovering Citizens in Post-Welfare Philadelphia. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth AJM, Hammersley RH, Lavelle TL, Murray KM. Geographical aspects of scoring illegal drugs. British Journal of Criminology. 1992;32(3):292–309. [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. Social Exclusion, Crime and Drugs. Drugs: education, prevention and policy. 2000;7(4):317–330. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Fahs M, Galea S, Vlahov D. Beyond Urban Penalty and Suburban Sprawl: Back to Living Conditions as the Focus of Public Health. Journal of Community Health. 2005;30(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-6091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galster G, Killen S. The geography of metropolitan opportunity: a reconnaissance and conceptual framework. Housing Policy Debate. 1995;6(1):73–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gans H. Involuntary Segregation and the Ghetto: Disconnecting Process and Place. City & Community. 2008;7(4):353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. The Pastoral Clinic: Addiction and Dispossession along the Rio Grande. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi S, Mingione E. Embeddedness, Path Dependency and Social Institutions. Current Sociology. 2007;55(1):11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gieryn T. A Place for Space in Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:463–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gobillion L, Selod H, Zenou Y. The Mechanisms of Spatial Mismatch. Urban Studies. 2007;44(12):2401–2427. [Google Scholar]

- Gough J, Eisenschitz A, McCulloch A. Spaces of Social Exclusion. Routledge; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grengs J. Cars Not Geography: Job Accessibility and Reconceptualizing Spatial Mismatch in Detroit. University of Michigan Urban and Regional Research Collaborative Working Paper Series # 07-04; 2006. Retrieved 7/13/09 at: http://sitemaker.umich.edu/urrcworkingpapers/search/da.data/1370271/Paper/grengs0704.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman TA. Mania Americana’: Narcotic Addiction and Modernity in the United States, 1870-1920. Journal of American History. 2004;90(4):1269–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RC. Race, Class and the State: The Metropolitan Enclave System in the United States. Insurgent Sociologist. 1980;10(2):45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RC, Negry C. Deindustrialization in the Great Lakes. Urban Affairs Quarterly. 1987;22.4:580–597. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking S. Pictures of a City: Scrappers. In: Oswalt P, editor. Shrinking Cities Volume1: International Research. Hatje Cantz; Berlin: 2005. pp. 470–477. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC. Landing a job in urban space: The extent and effects of spatial mismatch. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 2006;36:331–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Y.B.I. (Young Boy’s Inc.) The Autobiography of Butch Jones. H Publications; Detroit: 1996. as told to R. Canty. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RE. Heroin’s Hold on the Young. The New York Times; Jan 13, 2008. Retrieved 5/12/09, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/13/nyregion/nyregionspecial2/13heroinnj.html?_r=1&emc=eta1. [Google Scholar]

- Kain JF. Housing Segregation, Negro Employment, and Metropolitan Decentralization. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1968;82(2):175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kain JF. The spatial mismatch hypothesis: three decades later. Housing Policy Debates. 1992;3(2):371–460. [Google Scholar]

- Kain JF. A Pioneer’s Perspective on the Spatial Mismatch Literature. Urban Studies. 2004;41(1):7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kasarda JD. The Severely Distressed in Economically Transforming Cities. In: Harrell AV, Peterson GE, editors. Drugs, Crime and Social Isolation: Barriers to Urban Opportunity. The Urban Institute Press; Washington, D.C.: 1992. pp. 44–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kasarda JD, Appold SJ, Sweeney SH, Sieff E. Central City and Suburban Migration Patterns: Is a Turnaround on the Horizon? Housing Policy Debate. 1997;8(2):307–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kneebone E. Job Sprawl Revisited: The Changing Geography of Metropolitan Unemployment. The Brookings Institution, Metro Economy Series for the Metropolitan Policy Program. 2009 Apr 1-23; [Google Scholar]

- Kubler D, Walti S. Drug Policy-Making in Metropolitan Areas: Urban Conflicts and Governance. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2001;25(1):35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lalander P. Hooked on Heroin: Drugs and Drifters in a Globalized World. Berg; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Linebaugh J. Detroit’s Population Crashes. The Wall Street Journal. 2011 Mar 23; Retrieved 5/09/11 at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704461304576216850733151470.html.

- McLafferty S. Placing Substance Abuse: Geographical Perspectives on Substance Use and Addiction. In: Thomas YF, et al., editors. Geography and Drug Addiction. Springer Science; New York: 2008. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Meiklejohn ST. Overqualified Minority Youth in a Detroit Job Training Program: Implications for the Spatial and Skills Mismatch Debates. Economic Development Quarterly. 2002;16(4):342–359. [Google Scholar]

- Mieczkowksi T. Geeking Up and Throwing Down: Heroin and Street Life in Detroit. Criminology. 1986;24(4):645–666. [Google Scholar]

- Mieczkowksi T. Crack distribution in Detroit. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1990;17:9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Murji K. Hierarchies, Markets and Networks: Ethnicity/Race and Drug Distribution. Journal of Drug Issue. 2007;37(4):781–804. [Google Scholar]

- Musto DF. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Neill WJV. Marketing the Urban Experience: Reflections on the Place of Fear in the Promotional Strategies of Belfast, Detroit and Berlin. Urban Studies. 2001;38(5-6):815–828. [Google Scholar]

- Nikelly AG. The Role of Environment in Mental Health: Individual Empowerment Through Social Restructuring. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2001;37(3):305–323. [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides A, Zervos D. Rational Addiction With Learning and Regret. Journal of Political Economy. 1995;103(4):739–758. [Google Scholar]

- Parker H, Bakx K, Newcombe R. Living with Heroin: The impact of a drugs ‘epidemic’ on an English community. Open University Press; Philadelphia: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G, Hobbs D, Home Office Research Study 227 . Middle market drug distribution. Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate; London: 2001. Retrieved 12/22/10 at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/13878/1/Middle_market_drug_distribution.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Peck J. Work-Place: The Social Regulation of Labor Markets. Guilford; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Peck J, Theodore N. Carceral Chicago: Making the Ex-offender Employability Crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2008;32(2):251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pettiway LE. The mobility of robbery and burglary offenders in ghetto and non-ghetto spaces. Urban Affairs Quarterly. 1982;18(2):255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Pettiway LE. The Internal Structure of the Ghetto and the Criminal Commute. Journal of Black Studies. 1985;16(2):189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Polverento G, Schmidt C. Using GIS Mapping to Illustrate the Correlation Between Drug Use and Homicides in Wayne County—2008; Presented at the October 2009 Conference of the Michigan Association for Local Public Health (MALPH); Traverse City, Michigan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reese LR. Economic Versus Natural Disasters: If Detroit Had a Hurricane. Economic Development Quarterly. 2006;20(3):219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Reinarman C. Addiction as accomplishment: The discursive construction of disease. Addiction Research & Theory. 2005;13:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter P, Caulkins J. Illegal Lemons: Price Dispersion in the Cocaine and Heroin Markets. UN Bulletin on Narcotics. 2004:141–165. LVI. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter P, Haaga J. The organization of high-level drug markets: an exploratory study. Santa Monica, CA; Rand Corporation: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Riley JK. Crack, Powder Cocaine, and Heroin: Purchase and Use Patterns in Six Cities. National Institute of Justice and Office of National Drug Control Policy; 1997. Retrieved June 23, 2010 ( http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffiles/167265.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Roddy J, Steinmiller CL, Greenwald M. Heroin Purchasing is Income and Price-Sensitive. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0022631. published online March 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JE, Reynolds L, Deluca S. How Do Places Matter? The Geography of Opportunity, Self-efficacy and a Look Inside the Black Box of Residential Mobility. Housing Studies. 2002;17(1):71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhury C, Goodman A. Evidence of Racial Discrimination in Different Dimensions of Owner-Occupied Housing Search. Real Estate Economics. 1996;24(2):161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero V, Vass AA. Heroin use and the formal economy: illicit drugs and licit economies in Italy. British Journal of Criminology. 1992;32(3):273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Rugh JS, Massey DS. Racial Segregation and the American Foreclosure Crisis. American Sociological Review. 2010;75(5):629–651. doi: 10.1177/0003122410380868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini F, Salcedo R. Understanding Deep Urban Change: Patterns of Residential Segregation in Latin American Cities. In: Judd DR, Simpson D, editors. The City, Revisited. University of London Press; Minneapolis: 2011. pp. 332–355. [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MA, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and Estimation in Hidden Populations Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2004;34(1):193–240. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer J, Swickard J. Fatal Euphoria: Fentanyl: A Free Press Special Report. Detroit Free Press; Jun 24, 2007. Retrieved 5/12/09, http://www.freep.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/99999999/news05/70621038/ [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC. Smack: Heroin and the American City. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Bellaby P, Lindsay S. Social Inclusion at Different Scales in the Urban Environment: Locating the Community to Empower. Urban Studies. 2010;47:1439–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll MA. Job Sprawl and the Spatial Mismatch between Blacks and Jobs. The Brookings Institution, Metro Economy Series for the Metropolitan Policy Program. 2005 Feb 1-14; [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. Getting Paid”: Youth Crime and Work in the Inner City. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue T. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw E, Heynen NC. Urban Political Ecology, Justice and the Politics of Scale. Antipode. 2003;35(5):898–918. [Google Scholar]

- Templin N. Off the Books: For Inner-City Detroit, the Hidden Economy is Crucial Part of Life. The Wall Street Journal. 1995 Apr 4;A1 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. Redevelopment and Race: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny SC. Some new killing trick: Welfare reform and drug markets in a U.S. urban ghetto. Social Justice. 2001;28(4):49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez A, Cepeda A. The Relationship of Ecological Containment and Heroin Practices. In: Thomas YF, et al., editors. Geography and Drug Addiction. Springer Science; New York: 2008. pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Urban Outcasts: Stigma and Division in the Black American and the French Urban Periphery. International Journal of Urban and Regional Studies. 1993;17(3):366–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. The rise of advanced marginality: notes on its nature and implications. Acta Sociologica. 1996;39(2):121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Deadly Symbiosis: When Ghetto and Prison Meet and Mesh. Punishment and Society. 2001;3:95–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. Urban Desertification, Public Health, and Public Order: ‘Planned Shrinkage’, Violent Death, Substance Abuse and AIDS in the Bronx. Social Science and Medicine. 1990;31(7):801–813. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90175-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne County Sheriff’s Department Joint Law Enforcement Presentation to Detroit-Wayne County Drug Surveillance Group. 2009 Jul 16; [Google Scholar]

- Western B. Punishment and Inequality in America. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wial H, Friedhoff A. Bearing the Brunt: Manufacturing Job Loss in the Great Lakes Region, 1995-2005. The Brookings Institution, Metro Economy Series for the Metropolitan Policy Program. 2006 Jul 1-19; [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. Cities and Race: America’s New Black Ghettos. Routledge; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Wouters J. Spatiality and Growth Discourse: The Restructuring of America’s Rust Belt Cities. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2003;25(2):123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. Knopf; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yin L. The Dynamics of Residential Segregation in Buffalo: An Agent-Based Simulation. Urban Studies. 2009;46(13):2749–2770. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin S. How ‘Bad’ Is It?: Institutions and Intentions in the Study of the American Ghetto. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 1998;22(3):511–520. [Google Scholar]