Abstract

Cellular reprogramming involves profound alterations in genome-wide gene expression that is precisely controlled by a hypothetical epigenetic code. Small molecules have been shown to artificially induce epigenetic modifications in a sequence independent manner. Recently, we showed that specific DNA binding hairpin pyrrole-imidazole polyamides (PIPs) could be conjugated with chromatin modifying histone deacetylase inhibitors like SAHA to epigenetically activate certain pluripotent genes in mouse fibroblasts. In our steadfast progress to improve the efficiency of SAHA-PIPs, we identified a novel compound termed, δ that could dramatically induce the endogenous expression of Oct-3/4 and Nanog. Genome-wide gene analysis suggests that in just 24 h and at nM concentration, δ induced multiple pluripotency-associated genes including Rex1 and Cdh1 by more than ten-fold. δ treated MEFs also rapidly overcame the rate-limiting step of epithelial transition in cellular reprogramming by switching “ ” the complex transcriptional gene network.

” the complex transcriptional gene network.

Natural transcription factors precisely control genome-wide gene expression at various distinctive levels by switching “ON” and “OFF” the appropriate genes at the right place and time1. The eukaryotic genome is packaged into highly condensed chromatin and its functional unit nucleosomes are composed of histone proteins2. Histone tails protrude from the nucleosome structure and undergo precise covalent modifications to regulate chromatin dynamics and genome function3. Histone modifications regulate many genes in eukaryotic cells and control complex processes that govern cellular reprogramming4,5. It is known that histone-modifying enzymes including histone deacetylases (HDACs) are either rearranged and/or deleted in cancer cells and stem cells6,7. A recent study suggests that chromatin-modifying enzymes can act as both facilitators and barriers to epigenetic remodelling of differentiated cells to a stem cell configuration. Hence, selective chromatin modifiers could precisely modulate the complex transcriptional network with fewer exogenously introduced transcription factors and efficiently switch cellular identity8,9,10. In our lab, we have recently shown that it is possible to confer sequence-specificity to SAHA, a potent HDAC inhibitor by conjugating it with selective DNA-binding hairpin pyrrole-imidazole polyamides (PIPs)11. Consequently, we synthesized a new library of SAHA-PIPs with differential inducing ability termed, A to P and evaluated their effect on pluripotency genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). We identified some SAHA-PIPs that could differentially upregulate the endogenous expression of distinctive iPSC factors by initiating epigenetic marks conferring to transcriptionally active chromatin in the promoter region of both Oct-3/4 and Nanog12. Synthesis and screening of a series of derivatives of our hit SAHA-PIP E indicated that our programmable small DNA-binding SAHA-PIPs could be developed to induce the specific expression of core pluripotent genes13. However, the induction values were very low when compared to embryonic stem (ES) cells12,13. Our hypothesis is that the sequence-specific recognition ability of our first library of SAHA-PIPs is not sufficient enough to effectively induce gene expression. In this report, we show the synthesis, screening and identification of a new SAHA-PIP with improved recognition ability. Through genome-wide gene analysis we report for the first time about a novel small molecule that can rapidly activate multiple pluripotency genes, which are usually expressed at the later stages of reprogramming.

Results

Synthesis of novel SAHA-PIP conjugates with improved sequence-recognition ability and their characterization

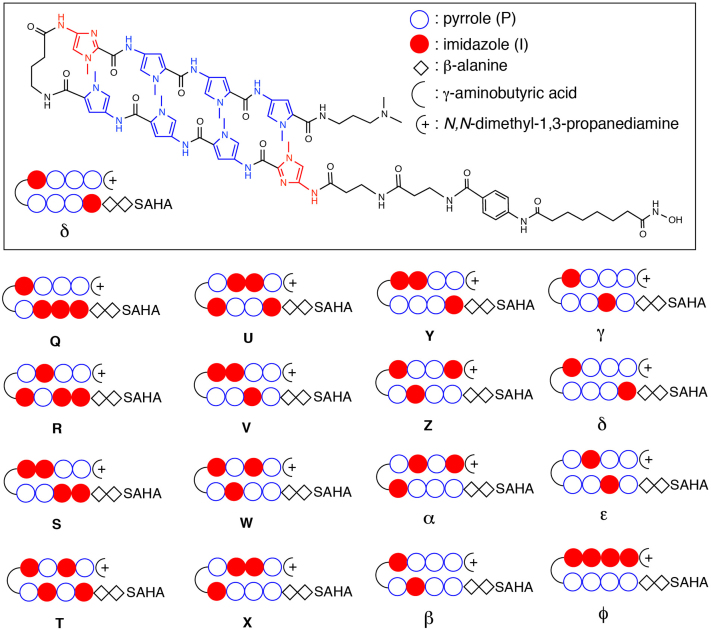

In this study, we designed 16 new SAHA-PIP conjugates that could differentially target a six-base-pair sequence according to the binding rule for PI polyamides. In these newly designed SAHA-PIP conjugates that were termed (Q to Φ), we placed imidazole at various positions in the top arm of the SAHA-PIPs (Figure 1). Our notion is that by placing imidazole at different positions, the selective inducing ability of SAHA-PIPs will be superior to our previous study owing to the improved recognition of GC rich sequences. The SAHA moiety was conjugated with a double β-alanine linker at the N-tail of the hairpin PI polyamides as mentioned before12,13 and all our SAHA-PIPs were expected to have high binding affinities (nM order) towards specific DNA sequences. We synthesized PI polyamides possessing (8-methoxy-8-oxooctanamido) benzoic acid moiety as a SAHA precursor through Fmoc solid-phase synthesis, using an oxime resin and subsequent 3-(dimethylamino)-1-propylamine treatment as mentioned before12. Consistent with the previous report, each of the synthesized precursors was converted to SAHA-PIPs (Q to Φ) by 50% (v/v) NH2OH. Q to Φ was then purified (Figure S1) and their Purity was confirmed by HPLC and ESI-TOF MS as described previously12,13.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of the synthetic SAHA-pyrrole (P)-imidazole (I) polyamide conjugates (PIPs) Q-Φ.

PIPs were designed by placing imidazole at various positions in their top arm for improved recognition of GC-rich sequences.

Identification of a novel SAHA-PIP that could dramatically induce iPSC reprogramming factors in mouse embryonic fibroblasts

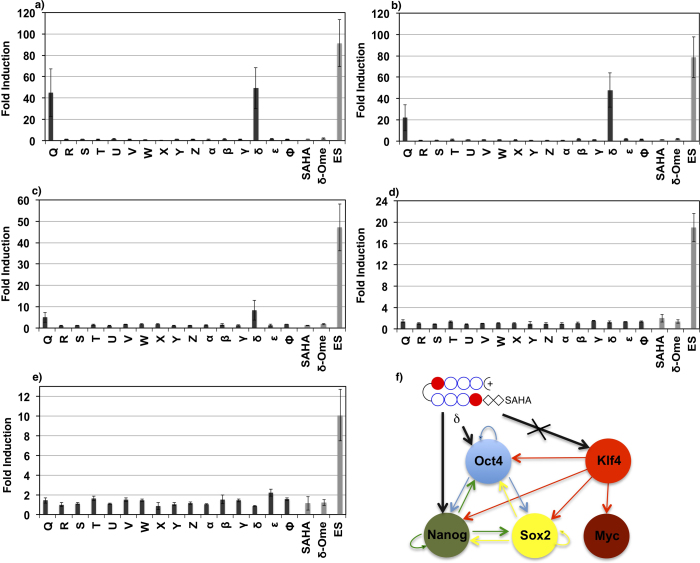

Screening studies to check the effect of our new library of 16 SAHA-polyamides (Q- Φ) on the endogenous expression of the standard reprogramming factors was done as mentioned before12,13. Q and δ dramatically induced the endogenous expression of Oct-3/4 by about 45 to 50-fold (Figure 2a, Bars Q and δ). Interestingly, δ also induced Nanog by about 47-fold; while Q treated MEFs displayed about 20-fold increase in the endogenous expression of Nanog (Figure 2b, Bars Q and δ). In the case of δ treated MEFs, Sox2 that belongs to the same core transcriptional network conferring to pluripotency showed about 8-fold increase in their endogenous gene expression, while Q treated MEFs showed about 4-fold induction (Figure 2c). Occasionally the induction values of Oct-3/4 and Nanog in δ treated MEFs were comparable to those in ES cells (Figure 2a and 2b, Bars δ and ES). It is important to note here that our hit SAHA-PIPs remarkably induce these critical pluripotency genes in just 24 h. Although Klf4 and c-Myc were not induced by any of the 16 SAHA-PIPs, it is known that their pathway14 is different from the core pluripotency gene network (Figure 2d and 2e). Based on our induction values, either Oct-3/4 or Nanog is suggested to be the direct target of δ, while the Klf4 pathway remains unaffected (Figure 2f).

Figure 2. Identification of novel SAHA-PIP that is specific to core transcriptional network: qRT-PCR analysis of the expression level of the iPSC factors a) Oct-3/4, b) Nanog, c) Sox2, d) Klf4, e) c-Myc.

Dark gray bars represent the expression profile of the endogenous genes with 100 nM of 16 individual SAHA-PIPs (Q-Φ). Light gray bar represent the control samples. ES cells were used as the positive control. SAHA with out PIP (100 nM) was used as the control to corroborate sequence-specificity. While, the SAHA-PIP δ conjugate that has a methyl ester in the functional group of SAHA (δ-OMe) was employed at the same concentration as a negative control to validate the importance of HDAC activity in endogenous gene expression. Each analysis was done at least three times in triplicate. Each bar represents mean ± SD from 18 well plates. f) Proposed mechanism of δ targeting Oct4 and Nanog based on the induction values but not the Klf4 that belongs to different transcriptional network.

SAHA with out PIP showed little or no induction of any iPSC factors suggesting that the PIP moiety conjugated with SAHA is the reason behind selective gene expression. To verify if the PIP δ moiety alone could induce endogenous gene expression, we synthesized a non-functional SAHA-PIP δ conjugate that possesses a methyl ester in the functional group of SAHA that causes HDAC inhibition (δ-OMe). Employment of the same concentration of δ-OMe did not have any effect on the endogenous expression of any iPSC factors, which suggests that SAHA moiety in δ is required for epigenetic activation of pluripotent genes (Figure 2a-e). δ displayed no cytotoxic effect on MEFs even at 1 μM, which implies that the cytotoxic effect is not correlated with gene inducing ability (Figure S2). The effective concentration of δ is just 100 nM, which is relatively lower than that of other small molecules used in cellular reprogramming12.

Genome-wide gene analysis of δ reveals induction of several important pluripotency-associated genes

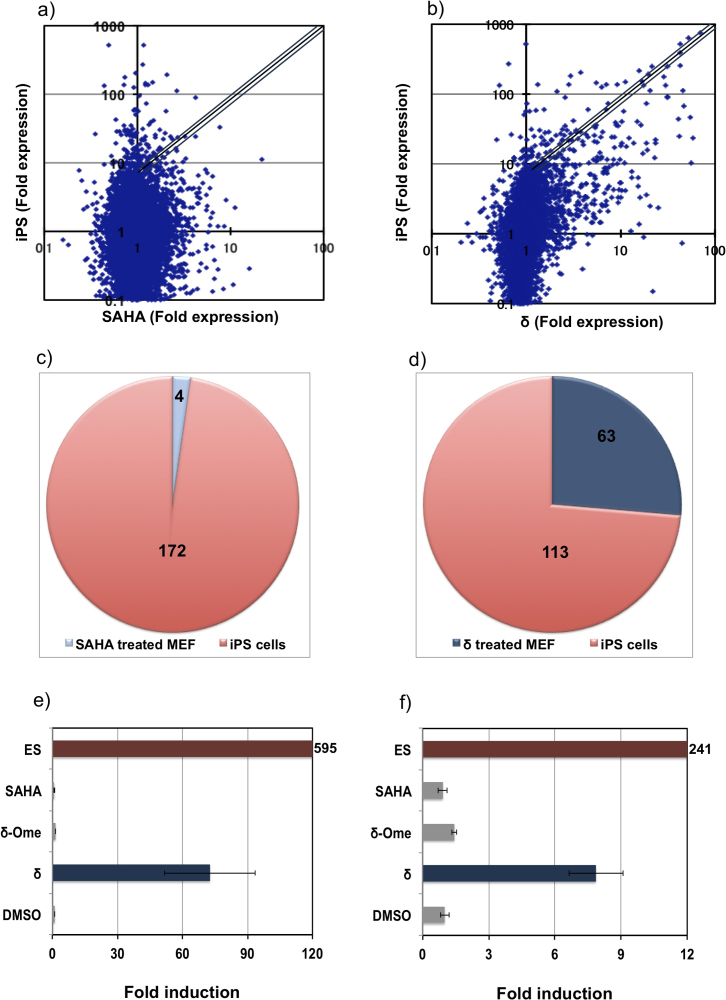

Cellular phenotype is modulated through a gradual epigenetic process that resets the transcriptional network15. Although Q and δ, notably induced Oct-3/4, we chose to evaluate the effect of δ on genome-wide gene expression as it also induced Nanog and hence, could have a remarkable effect on their downstream genes. Based on our previous report, we kept a three-fold increase and a two-fold decrease as the notable effect on the up-regulation and down-regulation, respectively12. In SAHA treated MEFs, out of 21,672 detected genes, about 150 genes were up-regulated and in δ treated MEFs out of 22,229 detected genes, about 305 genes were induced by more than three-fold (Tables S1 and S2). It is important to note here that δ treated MEFs up-regulated about twice the number of genes than SAHA treated MEFs, and down-regulated only 200 genes in comparison with 400 genes, which were down-regulated in SAHA treated MEFs (Tables S1 and S2). While screening for the genes that were induced at least by 10-fold, about 36% of the genes that were up regulated in δ treated MEFs were also observed in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)16 (Figure 3a–d). SAHA activated only 4% of the pluripotency-associated genes, which implies the role of the PIP in directing SAHA to genes conferring to pluripotency (Figure 3c). δ activated Rex1 and Dppa4, which are the critical pluripotency genes17 by about 70-fold and 7-fold, respectively (Figure 3e and f, Blue bars). The expression level of Rex1 and Dppa4 in ES cells was about 595-fold and 241-fold, respectively (Figure 3e and f, Red bars). SAHA only and the non-functional SAHA-PIP δ again did not affect the induction of these two genes (Figure 3e and f, Gray bars).

Figure 3. Effect of δ on genome-wide gene expression in MEFs.

Microarray scatter plots showing the global gene expression profile of a) SAHA and b) δ treated MEFs. The horizontal and vertical axis represents the expression profile of MEFs treated with either δ or SAHA and iPSCs, respectively. Ten-fold induction is kept as the cut-off for remarkable effect c) SAHA Vs iPS showed only 2% of the genes and d) δ Vs iPS showed about 36% of the genes that were shared with iPS. Analysis was done in duplicate. qRT-PCR analysis to check the effect of δ (Blue bars) on the endogenous expression of e) Rex1 and f) Dppa4 with DMSO, SAHA and non-functional SAHA-PIP δ (δ-Ome) as the negative control (Gray bars). ES cells were used as positive control (Red bars). Experiments were done in triplicate. The concentration of effectors (100 nM) and mean ± SD is from 12 wells.

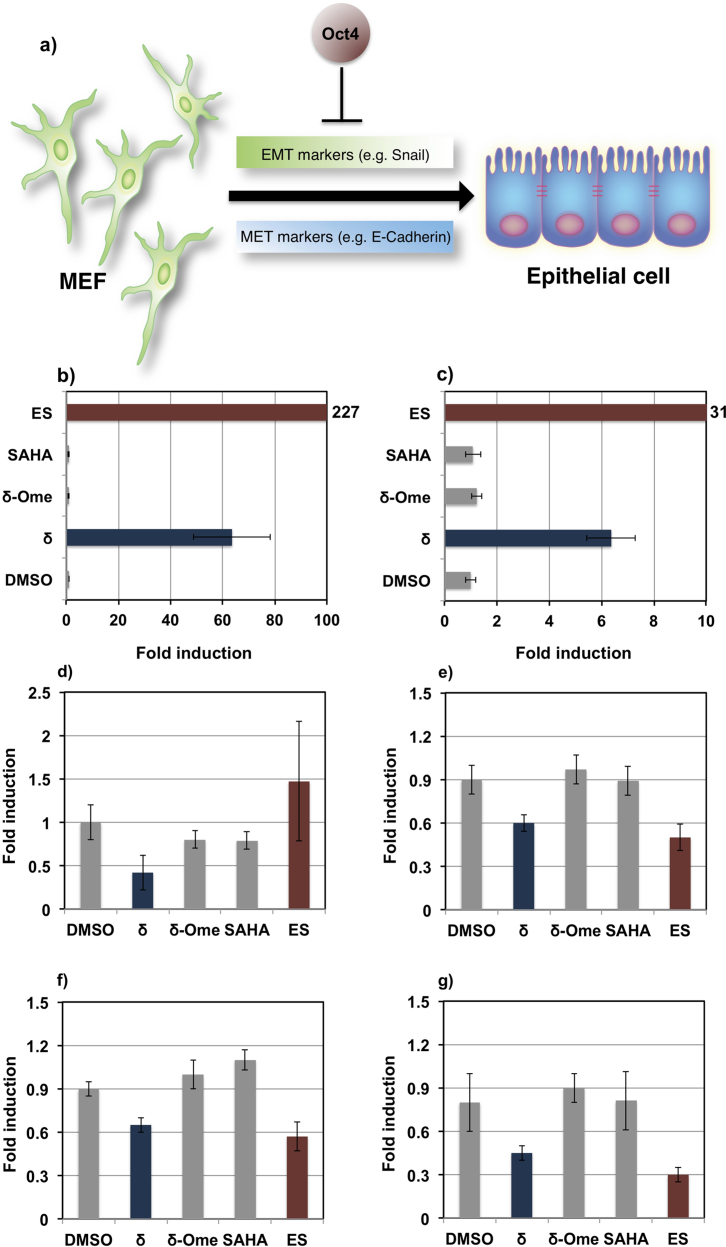

SAHA-PIP δ can rapidly initiate the critical mesenchymal epithelial transition stage to switch cell fate to pluripotency

Genome-wide gene analysis suggested that δ shifts the transcriptional network from fibroblasts to a de-differentiated state. MET (mesenchymal epithelial transition) is an important rate-limiting step during the de-differentiation of the somatic genome. The acquisition of an epithelial fate during cellular reprogramming appears to be closely associated with the pluripotent state, which reflects the need for cell-cell interactions that initiate and sustain pluripotency18. Several important pluripotent genes associated with cellular reprogramming that were rapidly induced by δ include the epithelial gene, Cdh1, which suggests that δ-treated MEFs could overcome MET stage that corresponds to initiation of cellular reprogramming19. To verify our micro array data, the endogenous expression of MET markers and EMT (Epithelial mesenchymal transition) markers were analyzed18. The critical up-regulated MET marker Cdh1 was dramatically induced by about 70-fold, which is remarkable as it transpires in just 24 h (Figure 4b, Blue bar) and with out the activation of Klf4, which is it’s upstream gene. Another up-regulated marker that is associated with MET, Cldn-7 was also notably induced by about 7-fold (Figure 4c, Blue bar). Cdh1 and Cldn-7 was induced by about 227 and 31-fold, respectively in ES cells (Figure 4b-c, Red bars).

Figure 4. Effect of δ on the endogenous expression of pluripotent genes associated with initiation of cellular reprogramming.

a) Initiation of cellular reprogramming from fibroblasts to epithelial cell intermediate involves the down-regulation of EMT (epithelial mesenchymal transition) and up-regulation of MET (mesenchymal epithelial transition) markers. Expression level of b) Cdh1, c) Cldn7, d) Fgf5, e) Zeb2, f) Snai1 and g) Snai2 in 100 nM of δ (Blue bars), δ-OMe, SAHA and DMSO treated MEFs (Gray bars). ES cells were used as positive control (Red bars). Experiments were done in triplicate and carried out twice. Each bar represents mean ± SD from 12 wells.

Fgf5 and some of the EMT markers including Snai1, Snai2 and Zeb2 were also down regulated by about 2-fold only in the case of δ-treated MEFs (Figure 4d–g, Blue bars).

No such effect was observed in control samples (4d–g, Gray bars). The expression pattern of the EMT markers was comparable to ES cells (Figure 4e–g, Red bars). Taken together, these results suggest that δ could rapidly overcome epithelial transition phase via specific initiation of pluripotency-related gene regulatory network.

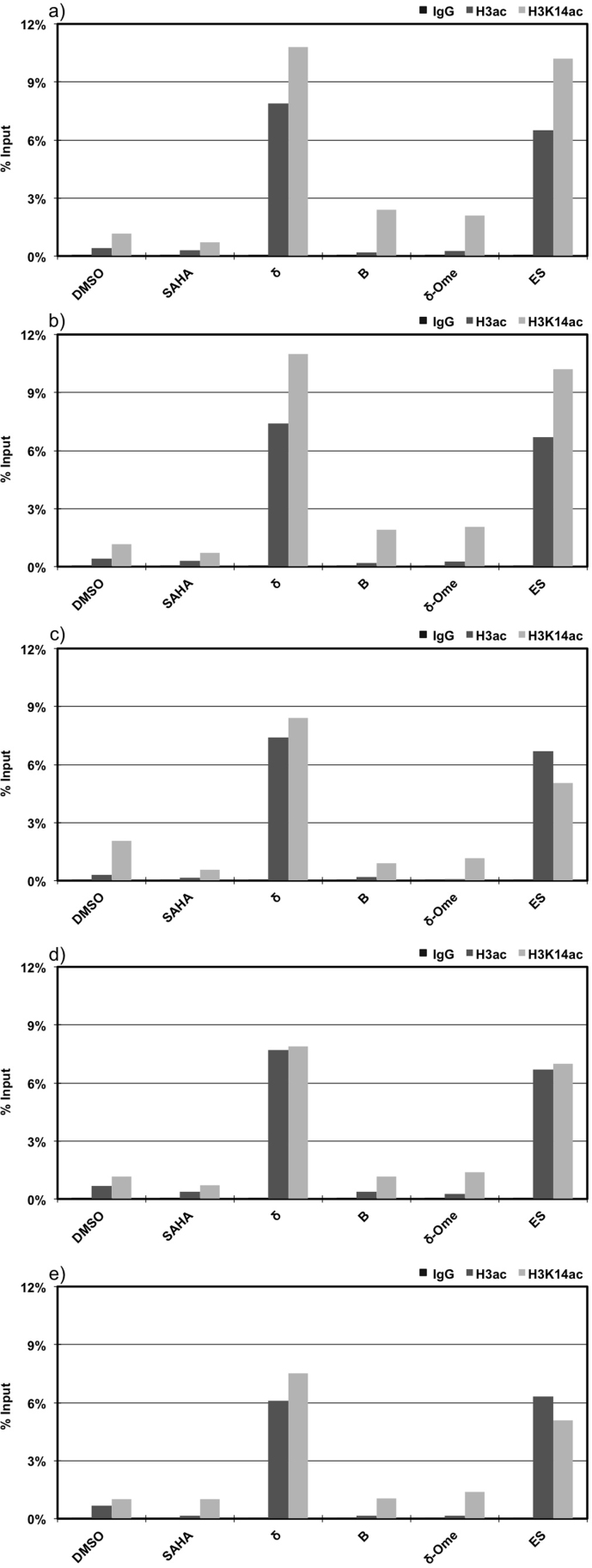

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay reveal hyper acetylation in the promoter region of core pluripotency genes

Consistent with the endogenous expression, the SAHA-PIP δ markedly induced the acetylation of histone H3 in the promoter region of Oct-3/4 and Nanog (Figure 5a and 5b, Bars H3ac). Increased acetylation of H3K14 reinstated that the inhibition of histone deacetylase occurs in the promoter region of these genes20 (Figure 5a and 5b, Bars H3K14ac). It is important to note here that sequence-specificity is corroborated again as SAHA only and the negative control B, did not induce acetylation of both histone H3 and H3K14 (Figure 5a and 5b, Bars B). The importance of HDAC activity is also substantiated, as the non-functional SAHA-PIP lacking HDAC activity did not have notable effect on acetylation of histone H3 in MEFs (Figure 5a and b, Bars δ-OMe), which suggests that both PIP δ and SAHA are essential for gene activation.

Figure 5. Both SAHA and PIP δ is essential for rapid induction of pluripotency genes.

MEFs were individually treated for 24 h with 100 nM of δ, δ-OMe, control SAHA-PIP (B), SAHA only and 0.1% DMSO. Mouse ES cells were used as positive control. After immunoprecipitation with H3ac and H3K14ac antibodies, the amount of promoter sequence of (a) Oct-3/4, (b) Nanog, (c) Dppa4, (d) Cdh1 and (e) Rex1 in the co-precipitated DNAs was determined by qPCR. Control samples including SAHA only and δ-OMe displayed no effect. Percent input is calculated by normalizing the data against input DNA, the enrichment with IgG antibody and with internal control primers. The primer sets are shown in Table S5. This experiment includes four treatments, each done in duplicate. Each bar represents the average of 9 wells.

A similar pattern was observed with Dppa4, Rex1 and Cdh1 where hyper acetylation of the histone H3 and H3K14 occurred in the promoter region of these pluripotency-associated genes (Figures 5c–e). Based on these results, it is reasonable to suggest that our hit SAHA-PIP δ-mediated gene induction occurs through the hyper acetylation of histone H3 caused by the HDAC activity of SAHA. Acetylation level of histone H3 and H3K14 in δ treated MEFs were comparable and occasionally surpass than that in ES cells (Figures 5a-e, Bars ES and δ).

Discussion

Chromatin modifications orchestrate the activation and suppression of the transcriptional machinery, which in turn controls the specification of cell type15,21,22. The code that characterizes the epigenetic modifications still remains elusive and hence deciphering their mode of functions represents a key-challenge in cell biology23,24. Since artificial chromatin modifiers are known to improve efficiency of cellular reprogramming by gene activation25,26,27, complementing them with site-specificity can enhance their efficacy. Previously we have shown that certain SAHA-PIPs can induce the expression level of both Oct-3/4 and Nanog with an added advantage of sequence-specific chromatin remodelling12. Although the induction effect of iPSC reprogramming factors by our hit SAHA-PIPs is notable, they were only three-fold. Among the newly developed SAHA-PIPs that possesses improved recognition ability, δ dramatically induced the multiple pluripotency genes to overcome the important MET phase, which has been a huge barrier of somatic cell reprogramming18. Epithelial cells are more flexible to reprogramming as acquisition of pre-existing features of pluripotent cells suggests that only fewer changes are required to attain pluripotency19. Recent studies indicate that epigenetic errors or cultural conditions could switch the cells to be prone to tumor formation28,29.

A recent report implied that neural differentiation from partially reprogrammed cells display superior and rapid gliogenic competency than those differentiated from either iPSCs or directly from somatic cells30. δ treated MEFs rapidly induce multiple pluripotency genes belonging to all three phases (Initiation, maturation and stabilization) of reprogramming (Table S3). We have already shown that it is possible to tailor cell-permeating PIPs to achieve improved induction values13. Hence, δ could be developed to rapidly trigger partially or completely reprogrammed configuration in somatic cells, which may eventually lead to superior differentiation. In δ treated MEFs, the induction values of some pluripotency-associated genes were similar to ES cells (Figure 2a, 2b and 4e–g). In some pluripotency genes, relatively lower induction values (5–10%) was observed in δ treated MEFs when compared to ES cells (Figures 3e, 3f and 4b–g). It is possible that the induction values in δ treated MEFs gets normalized by the MEFs that are elite or stochastically resistant to reprogramming. Hence, the induction values in δ treated MEFs are still remarkable as it could be obtained even with out the purification of the MEFs, which may be non-responsive to the treatment. Also, the induction values are notably higher when compared to the control samples treated with SAHA only, DMSO and PIP. Although, the actual six base pair binding site of δ is yet to be clarified, it should relatively bind to fewer matching sites owing to their palindromic architecture. We hypothesize that combinatorial binding of PIP to conserved sequences effect this rapid induction of pluripotency genes. PIPs gain the advantage over other natural mimics as they could perturb the architecture of the packed chromatin31. Studies on the specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules revealed PIPs are relatively superior to the natural DNA binding proteins32. Therefore, strategies to expand our tunable SAHA-PIPs could create an epoch-making approach in regenerative medicine to modulate the desired genes33,34.

Methods

Synthesis of SAHA-PIP `δ ` (SAHA-ββIPPPγΙPPPDp)

4-(8-methoxy-8-oxo-octa-namido) benzoic acid was synthesized and characterized as mentioned before11. PSSM-8 peptide synthesizer (Shimadzu, Kyoto) with a computer-assisted operating system using Fmoc chemistry was used for all polyamide syntheses with 45 mg of oxime resin (ca. 0.2 mmol/g, 200~400 mesh). As mentioned previously12, coupling and reaction steps were carried out to obtain the resin, which was then cleaved with N, N-dimethylaminopropylamine. The reaction mixture was filtered, triturated from Et2O, to yield 4-(8-methoxy-8-oxooctanamido) benzoyl PIP δ as a yellow crude powder. This pre SAHA-PIP (about 10 mg) was dissolved in DMF (0.5 ml) and was added to an aqueous solution of 50% (v/v) NH2OH (0.5 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred for 8 h at room temperature. After the reaction, hydroxylamine was quenched with acetic acid (0.5 ml) at 0°C. The mixture was purified by flash column chromatography. The purity was checked by HPLC (elution with trifluoroacetic acid and a 0–100% acetonitrile linear gradient (0–40 min) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 under 254 nm) to yield SAHA-PIP δ as a white powder (2.0 mg, 14%). ESI-TOF-MS (positive) m/z calcd for C76H97N25O152+ [M+2H]2+ 799.87; found 799.89.1H NMR (600 MHz, [D6] DMSO): δ = 10.32 (s, 1H), 10.27 (s, 1H), 10.25 (s, 1H), 10.06 (s, 1H), 9.97 (s, 1H), 9.96 (s, 1H), 9.94 (s, 2H), 9.89 (s, 2H), 9.23 (brs, 1H), 8.35 (brt, 1H), 8.15 (brt, 1H), 8.03 (brt, 1H), 8.00 (brt, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.9Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.9Hz, 2H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.43 (s, 1H), 7.27 (s, 2H), 7.22 (s, 2H), 7.17 (s, 2H), 7.16 (s, 2H), 7.07 (s, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 2.1Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 2.1Hz, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.43 (m, 2H), 3.33 (m, 2H), 3.24 (m, 2H), 3.21 (m, 2H), 3.07 (m, 2H), 2.79 (s, 3H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.52 (m, 2H), 2.47 (m, 2H), 2.37 (t, J = 7.6Hz, 2H), 2.35 (t, J = 7.6Hz, 2H), 2.31 (t, J = 7.6Hz, 2H), 1.93 (t, J = 7.6Hz, 2H), 1.84 (m, 2H), 1.79 (m, 2H), 1.57 (m, 2H), 1.48 (m, 2H), 1.26 (m, 2H).

A procedure similar to that used for the preparation of compound δ was adopted to prepare all the other SAHA-PIPs as shown below.

SAHA-PIP (Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z, α, β, γ, ε, φ)

SAHA-PIP Q (SAHA-ββIIIPγIPPPDp), SAHA-PIP R (SAHA-ββIIPIγPIPPDp), SAHA-PIP S (SAHA-ββIIPPγIIPPDp), SAHA-PIP T (SAHA-ββIPIPγIPIPDp), SAHA-PIP U (SAHA-ββIPPIγPIIPDp), SAHA-PIP V (SAHA-ββPIPPγIIPPDp), SAHA-PIP W (SAHA-ββPPΙPγIPIPDp), SAHA-PIP X (SAHA-ββPPPIγPIIPDp), SAHA-PIP Y (SAHA-ββIPPPγIIPPDp), SAHA-PIP Z (SAHA-ββPPIPγIPPIDp), SAHA-PIP α (SAHA-ββPPPIγPIPIDp), SAHA-PIP β (SAHA-ββPPIPγIPPPDp), SAHA-PIP γ (SAHA-ββPIPPγIPPPDp) and SAHA-PIP ε (SAHA-ββPIPPγPIPPDp) and SAHA-PIP φ (SAHA-ββPPPPγIIIIDp)

Other experimental details are submitted as supplementary information along with this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Experiments were designed by H.S., T.B., H.N. and G.N.P. G.N.P. S.S., Y.N and G.N.P performed research. H.S., G.N.P., Y.N., S.S. and H.M analyzed the data. The manuscript was written by H.S., G.N.P. and T.B.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan. The iCeMS is supported by World Premier International Research Center Initiative, MEXT, Japan. We thank Nagase Science and Technology foundation for their support. We thank iCeMS exploratory grant and Grants-in-aid for Young Scientists-B for support to G. N. P. We are also thankful to Mrs. Sekar Latha for graphical design.

References

- Ptashne M. & Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature 386, 569–577 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore D. Our genome unveiled. Nature 409, 814–816 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna S. D., Li H., Ruthenburg A. J., Allis C. D. & Patel D. J. How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1025–1040 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128, 693–705 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zupkovitz G. et al. Negative and positive regulation of gene expression by mouse histone deacetylase 1. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 7913–7928 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L., Anderson J. N. & Futreal P. A. Cancer genomics: from discovery science to personalized medicine. Nat. Med. 17, 297–303 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Corsello T. R. & Yupo M. Stem cell gene SALL4 suppresses transcription through recruitment of DNA Methyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1996–2005 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder T. T. et al. Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature 483, 598–602 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai H. et al. Radical acceleration of nuclear reprogramming by chromatin Remodeling with the Transactivation Domain of MyoD. Stem cells 29, 1349–1361 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj V., Plane J. M., Williams A. J. & Deng W. Switching cell fate: the remarkable rise of induced pluripotent stem cells and lineage reprogramming technologies. Trends in Biotech 28, 214–223 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki A. et al. Synthesis and properties of PI polyamide-SAHA conjugate. Tetrahedron Lett 50, 7288–7292 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pandian G. N. et al. Synthetic small molecules for epigenetic activation of pluripotent genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. ChemBioChem 12, 2822–2828 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandian G. N. et al. Development of programmable small DNA-binding molecules with epigenetic activity for induction of core pluripotency genes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 2656–2660 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfa K. T. & Eggan K. A transcriptional logic for nuclear reprogramming. Cell 126, 652–655 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Olguin P. & Recillas-Targa F. Chromatin structure of pluripotent stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Brief. Funct. Genomics. 10, 37–49 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan R. et al. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell 136, 364–377 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh Y. H. et al. Genomic approaches to deconstruct pluripotency. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 12, 165–185 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 7, 51–63 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavarchi-Tehrani P. et al. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 7, 64–77 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson A. et al. HAT-HDAC interplay modulates global histone H3K14 acetylation in gene-coding regions during stress. EMBO Rep. 10, 1009–1014 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner D. E. & Berger S. L. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 435–459 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlabach M. R. et al. Cancer proliferation gene discovery through functional genomics. Science 319, 620–624 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T. & Allis C. D. Translating the histone code. Science 293, 1074–1080 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuara V. et al. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 532–538 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 3, 568–574 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D. et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1269–1275 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P. et al. Butyrate greatly enhances derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by promoting epigenetic remodeling and the expression of pluripotency associated genes. Stem Cells. 28, 713–720 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. et al. A model of cancer stem cells derived from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS ONE 7, e33544 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 467, 285–290 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T. et al. Neural stem cells directly differentiated from partially reprogrammed fibroblasts rapidly acquire gliogenic competency. Stem cells. DOI:10.1002/stem.1091 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove A. J. & Voytas D. F. TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science 333, 1843–1846 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C. D. et al. Specificity landscapes of DNA binding molecules elucidate biological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 4544–4549 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandian G. N. & Sugiyama H. Programmable genetic switches to control transcriptional machinery of pluripotency. Biotechnol. J. 7, 798–8091 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwazaki G. et al. Synthesis and biological properties of highly sequence-specific-alkylating N-Methylpyrrole–N-Methylimidazole polyamide conjugates. J. Med. Chem. 55, 2057–2066 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information