Background: The functions of NF-κB in apoptosis and tumor development are controversial.

Results: Fas functions as a tumor suppressor, and NF-κB directly binds to multiple sites in the Fas promoter region to regulate Fas transcription.

Conclusion: Canonical NF-κB is a Fas transcription activator, whereas alternate NF-κB is a Fas transcription repressor.

Significance: Inhibition of NF-κB in cancer therapy might suppress Fas-mediated apoptosis to impair host immune cell-mediated tumor suppression.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cancer, Cancer Tumor Promoter, Fas, NF-kappaB, NF-kappaB Transcription Factor

Abstract

Fas is a member of the death receptor family. Stimulation of Fas leads to induction of apoptotic signals, such as caspase 8 activation, as well as “non-apoptotic” cellular responses, notably NF-κB activation. Convincing experimental data have identified NF-κB as a critical promoter of cancer development, creating a solid rationale for the development of antitumor therapy that suppresses NF-κB activity. On the other hand, compelling data have also shown that NF-κB activity enhances tumor cell sensitivity to apoptosis and senescence. Furthermore, although stimulation of Fas activates NF-κB, the function of NF-κB in the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway remains largely undefined. In this study, we observed that deficiency of either Fas or FasL resulted in significantly increased incidence of 3-methylcholanthrene-induced spontaneous sarcoma development in mice. Furthermore, Fas-deficient mice also exhibited significantly greater incidence of azoxymethane and dextran sodium sulfate-induced colon carcinoma. In addition, human colorectal cancer patients with high Fas protein in their tumor cells had a longer time before recurrence occurred. Engagement of Fas with FasL triggered NF-κB activation. Interestingly, canonical NF-κB was found to directly bind to the FAS promoter. Blocking canonical NF-κB activation diminished Fas expression, whereas blocking alternate NF-κB increased Fas expression in human carcinoma cells. Moreover, although canonical NF-κB protected mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis, knocking out p65 diminished Fas expression in MEF cells, resulting in inhibition of FasL-induced caspase 8 activation and apoptosis. In contrast, knocking out p52 increased Fas expression in MEF cells. Our observations suggest that canonical NF-κB is a Fas transcription activator and alternate NF-κB is a Fas transcription repressor, and Fas functions as a suppressor of spontaneous sarcoma and colon carcinoma.

Introduction

CD95 (also termed APO-1, Fas, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6, or TNFRSF6) is a member of the death receptor family, a subfamily of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. Binding to Fas by its physiological ligand, FasL, triggers receptor trimerization, followed by formation of death-inducing signaling complex and subsequent apoptosis (1–3). Germ line and somatic mutations or deletions of Fas or FasL gene coding sequences in humans lead to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (4–8), suggesting a critical role of the Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway in lymphocyte homeostasis and suppression of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome patients also exhibited increased risk of both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cancers (4, 7, 9). Furthermore, both the Fas and FasL gene promoters are polymorphic, including a G to A substitution at −1377 bp and an A to G substitution at −670 bp at the Fas gene promoter and a C to T substitution at −844 and a −124 A to G substitution at the FasL gene promoter. These polymorphisms diminish transcription factor binding to the Fas and FasL promoter and Fas/FasL expression level and are also associated with increased risk of both hematopoietic malignancies and non-hematopoietic carcinoma development in humans (10–15). These observations thus suggest that Fas functions not only in inhibition of human autoimmune diseases but also in suppression of cancer development in humans.

Stimulation of the Fas receptor, however, has also been shown to activate “non-apoptotic” signaling, notably NF-κB activation (16–18). In addition, it has been shown that loss of Fas in mouse models of ovarian and liver cancers reduces tumor incidence and tumor sizes (19). These observations lead to the proposal that Fas activity should be inhibited in cancer therapy (19). However, details of Fas-mediated “non-apoptotic” signaling pathways remain largely unknown (1). Importantly, although convincing experimental data have established NF-κB as a tumor-promoting transcription factor (20), compelling recent studies have started to shed light on the function of NF-κB as a promoter of apoptosis and senescence (21–28). More importantly, it has been shown that NF-κB mediates recruitment of FADD and caspase 8 to the death-inducing signaling complex to increase tumor cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis in tumor cells (28). Furthermore, NF-κB was found to regulate TNFα and IFN-γ expression to up-regulate Fas expression (29). These studies thus demonstrate that NF-κB mediates tumor cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

We report here that NF-κB directly regulates Fas transcription in human colon carcinoma cells and in MEF cells. Our data indicate that canonical NF-κB is a transcription activator of Fas and alternate NF-κB is a transcription repressor of Fas, and Fas functions as a tumor suppressor. Therefore, caution should be exercised in utilizing blockage of NF-κB activity as a broad therapeutic strategy in cancer therapy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

The method of sarcoma induction using 3-methylcholanthrene (MCA)3 was as previously described (30). Briefly, MCA was used at a dose of 100 μg in 100 μl of peanut oil as described previously (30) and was injected subcutaneously into B6.MRL-Faslpr/J (n = 10), WT C57BL/6J (n = 10), CPt.C3-Faslgld/J (n = 23), and BALB/c (n = 14) mice. To induce colon cancer, the well established azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) procedure was used (31). Briefly, AOM (10 mg/kg body weight) was injected intraperitoneally into B6.MRL-Faslpr/J (n = 3) and WT C57BL/6J (n = 5) mice. The drinking water of the mice was replaced with DSS (2.25%) the day after AOM injection for 1 week. After four cycles of water (2 weeks) and DSS (1 week), the mice were maintained with regular water for 33 more days and examined for colon cancer development.

Cells

All human tumor cell lines used in this study were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). p65 KO and the matched p65 WT MEF cells were provided by Dr. Karen H. Vousden (NCI, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, MD) (32). p52 KO and matched p52 WT MEF cells were provided by Dr. Kenneth B. Marcu (Stony Brook University, New York) (33).

Reagent

IKKβ-KA and IKKα-KM plasmids were provided by Warner C. Greene (University of California, San Francisco, CA) (34). Mega-Fas Ligand® (kindly provided by Drs. Steven Butcher and Lars Damstrup, Topotarget A/S, Denmark) is a recombinant fusion protein that consists of three human FasL extracellular domains linked to a protein backbone comprising the dimer-forming collagen domain of human adiponectin. The Mega-Fas ligand was produced as a glycoprotein in mammalian cells using good manufacturing practice-compliant processes in Topotarget A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark). IFN-γ and TNFα were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Human Colorectal Carcinoma Specimens

Colon cancer tissue microarray slides were provided by the NCI, National Institutes of Health, Cancer Diagnosis Program. The tissue microarrays contain 341 stage I–IV colorectal cancer specimens and were designed by NCI statisticians for high statistical power for examination of associations of markers with tumor stage, clinical outcome, and other clinical-pathologic variables. Specimen information is listed in supplemental Table 1.

Tumor Viability Assay

Tumor cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured in the presence of IFN-γ, FasL, or both IFN-γ and FasL for 3 days. The cell viability assay was carried out using the MTT cell proliferation assay kit (ATCC).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (35) using CD8 antibody (DAKO Corp.) at a 1:250 dilution and anti-Fas (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and used for semiquantitative and real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression as described (36, 37). The PCR primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 2.

Western Blotting Analysis

Cytosol and mitochondrion-enriched fractions were prepared as described previously (38). Western blotting analysis was performed as described previously (35). Anti-cleaved caspase 8 was obtained from R&D Systems. Anti-β-actin was obtained from Sigma.

Apoptosis Assays

Cells were either stained with propidium iodide (PI) (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) or PI plus Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 647 (Biolegend) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cell Surface Fas Protein Analysis

Human tumor cells were stained with anti-human Fas mAb (Biolegend). MEFs were stained with anti-mouse Fas mAb (Biolegend). Isotype-matched control IgGs (Biolegend) were used as negative controls. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were carried out according to protocols from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY) as described previously (36). Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-pSTAT1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-p50 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), respectively, followed by pull-down with agarose-protein A beads (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.). PCR primers are listed in supplemental Table 2.

Electrophoresis Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) of NF-κB Activation

NF-κB activation was analyzed using an NF-κB probe (AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and probes with NF-κB consensus sequences of the Fas promoter region (supplemental Table 2) as described previously (35). Briefly, the end-labeled probes were incubated with nuclear extracts for 20 min at room temperature. For specificity controls, unlabeled probe or mutant probe was added to the reaction at a 1:100 molar excess. Anti-p65, -p52, and -p50 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were also included to identify NF-κB-specific DNA binding. DNA-protein complexes were separated by electrophoresis in 6% polyacrylamide gels and identified using a PhosphorImager screen (GE Healthcare), and the images were acquired using a Storm 860 imager (GE Healthcare).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2, and statistical significance was assessed using an α level of 0.05. χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used to examine differences in tumor stage, node stage, metastasis stage, and summary stage by Fas stain intensity (bright versus dim), CD8 T cell infiltration level (low versus high), and a combination of Fas stain intensity and CD8 T cell infiltration level. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to examine differences in time to recurrence by Fas stain intensity, CD8 T cell infiltration level, and a combination between Fas stain intensity and CD8 T cell infiltration level. A log rank test was used to assess differences in survival between the groups.

RESULTS

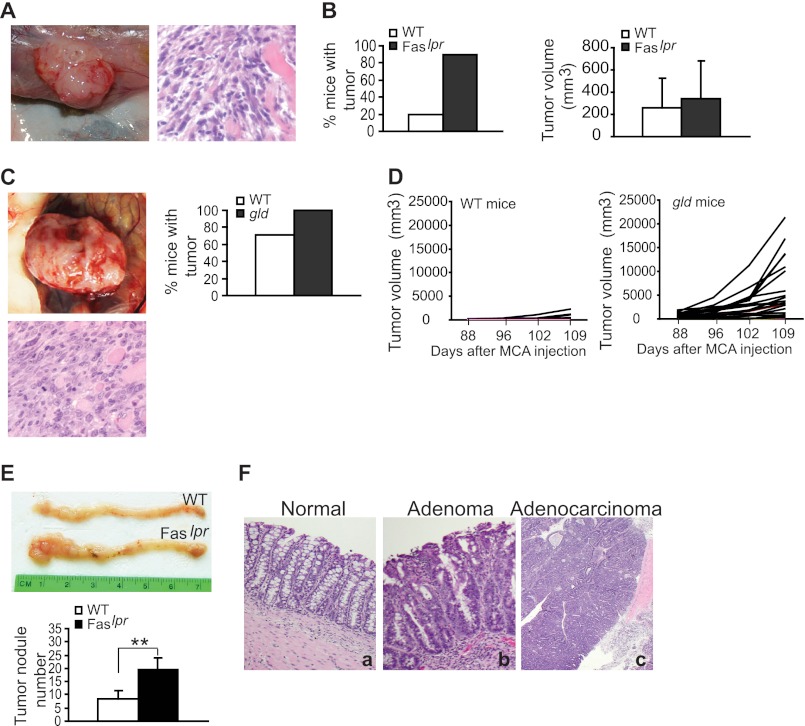

Loss of Fas or FasL Function Leads to Increased Spontaneous Sarcoma Development

Because membrane-bound FasL only induces Fas-mediated apoptosis and membrane-bound FasL is primarily expressed on activated lymphocytes (39, 40), it is thus critical to examine Fas function in a tumor microenvironment where tumors are immunogenic and lymphocyte infiltrates are present. The MCA-induced spontaneous sarcoma is an immunogenic mouse tumor model, and the host lymphocytes are actively involved in anti-tumor immunity in sarcoma-bearing hosts (30). MCA was injected into Faslpr (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J) and Fasgld (CPt.C3-Faslgld/J) mice, respectively, and examined for spontaneous sarcoma development. Ninety percent (9 of 10) of Faslpr mice and 100% (23 of 23) of Fasgld mice developed high grade sarcoma (Fig. 1, A and C), respectively, whereas only 20% (2 of 10) of WT Fas C57BL/6J mice and 71% (10 of 14) of Fas WT BALB/c mice developed tumors (Fig. 1, B and D). Although the tumor sizes were not significantly different between Faslpr mice and WT C57BL/6J control mice (Fig. 1B), tumors in Fasgld mice grew significantly faster than in WT BALB/c control mice (Fig. 1D). As a complementary mouse tumor model, we also used the AOM-DSS-induced spontaneous colon carcinoma mouse model to examine the function of Fas in tumor development. Faslpr and C57BL/6J mice were treated with AOM-DSS and observed for spontaneous colon carcinoma development. AOM-DSS induced a higher colon cancer incidence in Faslpr mice as compared with the WT C57BL/6J control mice (Fig. 1, E and F). Taken together, our data suggest that Fas functions as a suppressor of spontaneous sarcoma and colon carcinoma.

FIGURE 1.

Loss of Fas function increased spontaneous sarcoma and colon carcinoma development. A, MCA was injected into WT (n = 10) and Faslpr (n = 10) mice subcutaneously and analyzed for sarcoma development 102 days later. Shown are live sarcoma in a tumor-bearing mouse (left) and H&E-stained tumor section (right). B, tumor incidence (left) and size (right). Columns, mean; error bars, S.D. C, MCA was injected into WT (n = 14) and Fasgld (n = 23) mice and analyzed for sarcoma development. Shown are live sarcoma in a tumor-bearing mice (top left), an H&E-stained section of the sarcoma (bottom), and tumor incidence (top right). D, tumor growth kinetics in WT (left) and Fasgld mice (right). MCA-induced sarcomas as shown in C were measured for sizes over time. E, AOM-DSS-induced colon carcinoma in WT and Faslpr mice. WT (n = 5) and Faslpr (n = 3) mice were treated with AOM and DSS as described under “Experimental Procedures” and examined for colon cancer development. Morphology of tumor-bearing colon tissues are shown (top). The tumor nodule number was counted and is presented at the bottom. Columns, mean; error bars, S.D. **, p < 0.01. F, histological analysis of the AOM-DSS-induced colon carcinoma as shown in E. The tumor sections were stained with H&E. a, normal colon tissue; b, adenoma; c, adenocarcinoma.

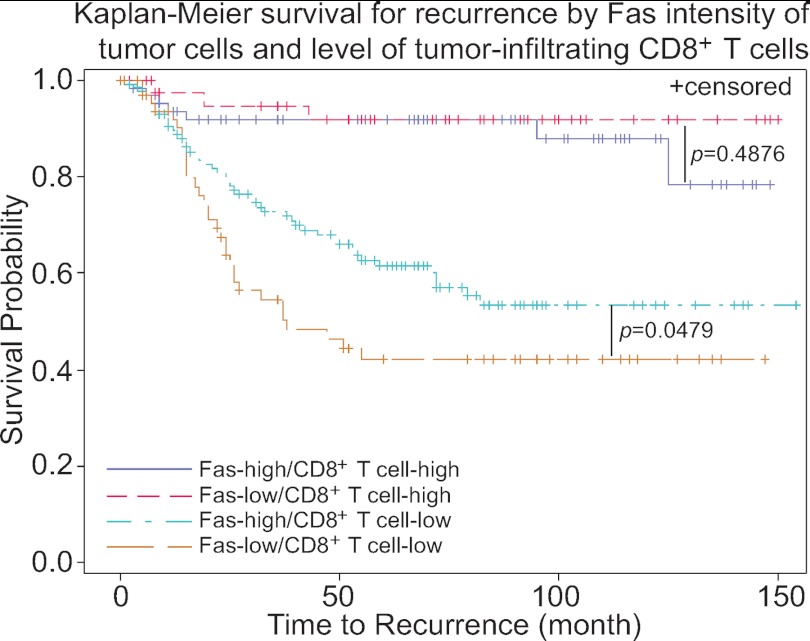

Correlation between Fas Level and Cancer Recurrence in Human Colorectal Cancer Patients

Fas is frequently silenced in human cancer, especially in metastatic cancer cells (41), suggesting that human cancer cells might use loss of Fas as a means to advance the disease. To determine the relationship between Fas expression level and colorectal cancer development in humans, we used an immunohistochemical approach to examine Fas protein level in a large cohort of human colorectal cancer specimens (n = 341). Analysis of Fas protein levels in these 341 CRC patients revealed that the average time to cancer recurrence for patients with a high Fas level in the tumor cells is 93.82 months, whereas that time is only 47.4 months for patients with low Fas protein level in the tumor cells (Table 1). However, due to the large variations in times to recurrence among patients, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.35). The level of CD8+ T cell infiltration in the tumor is positively correlated with decreased recurrence (Table 1) (p = 0.0001). No correlation between Fas level and tumor stages was observed.

TABLE 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival on recurrence

| Variable | Level | Mean recurrence timea | S.D. | Log rank test p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| months | ||||

| Fas protein | Bright | 93.82 | 3.59 | |

| Dim | 47.4 | 1.98 | 0.3496 | |

| CD8+ T cells | High | 113.79 | 3.37 | |

| Low | 55.83 | 2.26 | 0.0001 | |

| Fas protein/CD8+ T cell | Bright/Low | 59.91 | 2.72 | |

| Dim/Low | 36.86 | 2.46 | 0.0479 | |

| Bright/High | 114.39 | 4.50 | ||

| Dim/High | 41.48 | 1.30 | 0.4876 |

a Length of time (in months) from date of cancer diagnosis to first recurrence or last verified recurrence-free.

Because Fas receptor alone does not initiate cellular signals and FasL is the physiological ligand of Fas (42), that is primarily expressed on activated lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T cells (40), we analyzed CD8+ T cell infiltration level in these tumor specimens. As expected, CTL infiltration level is positively correlated with decreased recurrence (p = 0.0001) (43, 44). Although no correlation was observed between Fas level and recurrence time in patients with high levels of CD8+ T cell infiltration, patients with high Fas protein levels in the tumor cells generally have a longer time before recurrence occurs when CD8+ T cell infiltration level in their tumor cells is low (Table 1 and Fig. 2) (p = 0.048). The mean recurrence time is 59.91 months for patients with a high Fas protein level and 36.86 months for patients with a low Fas protein level, respectively (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Correlation between Fas protein level, CD8+ T cells, and cancer recurrence in human colorectal cancer patients. Tissue microarray slides containing human colorectal cancer specimens (n = 341, supplemental Table 1) were stained for tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and Fas protein level. The stained specimens were then graded and statistically analyzed for correlation with cancer recurrence. Each variable is indicated by colored lines in the plot.

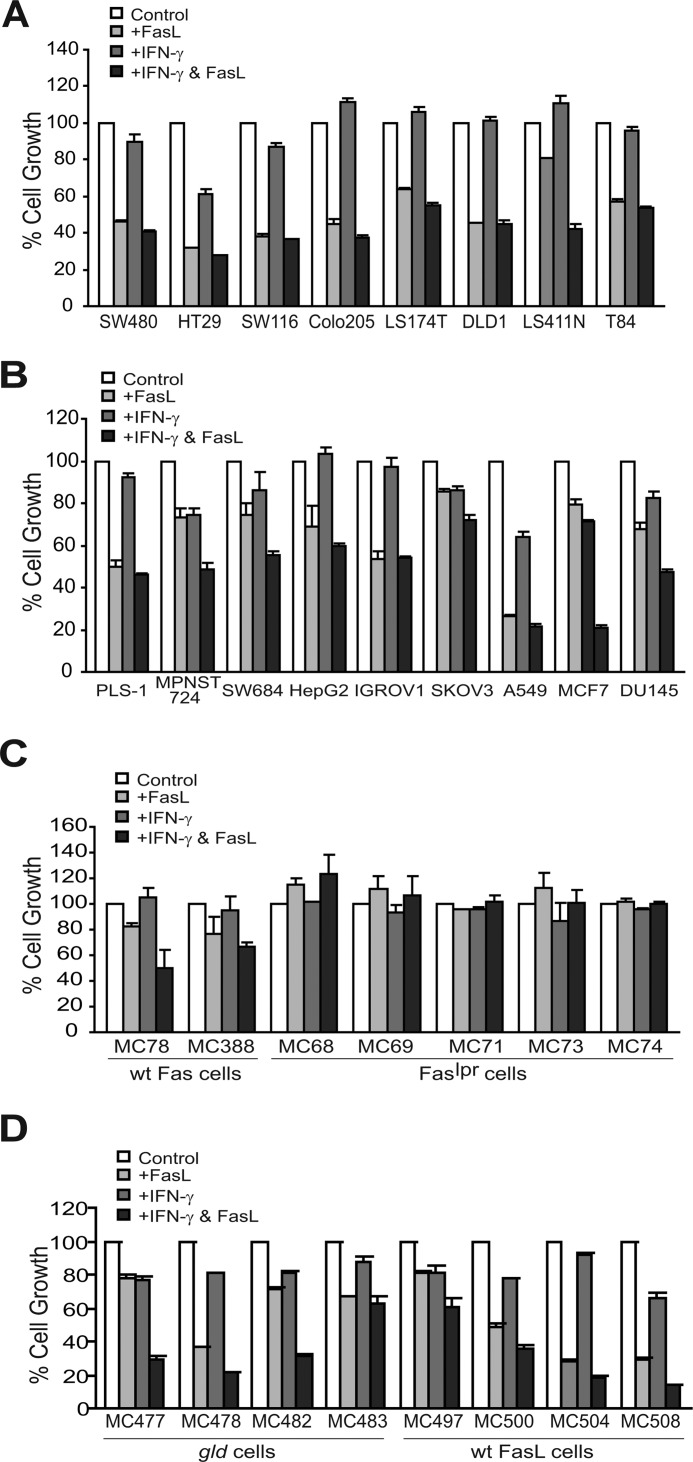

FasL Induces Tumor Growth Inhibition in Vitro

To determine whether FasL induces apoptosis (45) or promotes tumor cell growth (19), eight human colon carcinoma cell lines were cultured in the presence of FasL in vitro and measured for cell growth. Because certain tumor cells are resistant to apoptosis and IFN-γ sensitizes tumor cells to apoptosis induction (35), IFN-γ treatment was included for each cell line. It is clear that FasL inhibited the growth of all nine cell lines in vitro (Fig. 3A). Next, nine human cancer cell lines of six types of cancers, including sarcoma (PLS-1, MPNST724, and SW116), hepatoma (HepG2), ovarian carcinoma (IGROV1 and SKOV3), lung carcinoma (A549), mammary carcinoma (MCF7), and prostate cancer (DU145), were tested for their sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. All nine cell lines are sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, IFN-γ increased the sensitivity of six cell lines to FasL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3B). Our data thus indicate that Fas-FasL interaction suppresses human cancer cell growth in vitro.

FIGURE 3.

FasL specifically induces tumor cell growth inhibition through Fas receptor in vitro. A, eight human colon carcinoma cell lines were incubated with IFN-γ, FasL, or both IFN-γ and FasL for 3 days and analyzed for growth inhibition by MTT assays. The growth rate of untreated cells was set at 100%. % Cell Growth, percentage of cell growth as measured by MTT assays of treated cells over untreated cells. Columns, mean; bars, S.D. B, multiple types of human cancer cells were analyzed for sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis as in A. The cell lines are indicated below the plot. C, FasL induces tumor cell growth inhibition specifically through the Fas receptor. Tumor cell lines were established from sarcomas derived from tumor-bearing WT (n = 2) and Faslpr (n = 5) mice as shown in Fig. 1A and incubated with IFN-γ, FasL, or both IFN-γ and FasL for 3 days and analyzed for growth inhibition by MTT assay as in A. D, loss of FasL in tumor cells does not affect tumor cell sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. Tumor cell lines were established from tumor-bearing WT (n = 4) and Fasgld (n = 4) mice as shown in Fig. 1C and analyzed by MTT assay as in A.

To determine the specificity of FasL-induced apoptosis, we first established sarcoma cell lines from WT and Faslpr tumors derived from the tumor-bearing mice, as shown in Fig. 1, and examined the response of these tumor cell lines to FasL. Incubation of FasL with WT sarcoma tumor cells induced tumor cell growth inhibition, whereas Faslpr tumor cells exhibited no response to the FasL treatment (Fig. 3C). Next, we established sarcoma cell lines from WT and Fasgld mice and examined the sensitivity of these cell lines to FasL. Both WT and Fasgld sarcoma cell lines are sensitive to FasL-mediated growth inhibition (Fig. 3D). In summary, our data suggest that FasL induces tumor cell growth inhibition specifically through the Fas receptor.

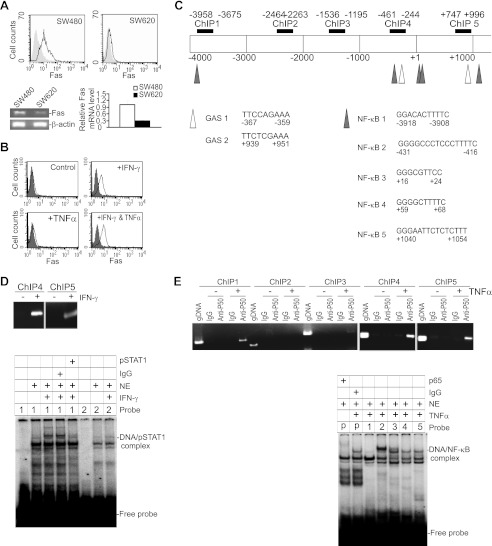

IFN-γ and TNFα Up-regulate Fas Expression through pSTAT1 and NF-κB Binding to the FAS Promoter

Human metastatic colon carcinoma cells often exhibit diminished Fas expression (41) (Fig. 4A). It has been shown that IFN-γ and TNFα, cytokines secreted by senescent tumor cells and activated immune cells, can up-regulate Fas expression (29, 46, 47). Indeed, IFN-γ and TNFα synergistically up-regulated Fas in human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 4B). Consistent with increased Fas expression, the metastatic colon carcinoma cells became sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis (supplemental Fig. S1). To determine whether IFN-γ-activated pSTAT1 and TNFα-activated NF-κB directly bind to the FAS promoter to activate FAS transcription, we performed ChIP assays of the human FAS gene promoter from −4000 to +1000 relative to the FAS gene transcription initiation site. Immunoprecipitation with pSTAT1- and p50-specific antibodies revealed that both pSTAT1 and NK-κB bind to multiple regions of the FAS gene promoter chromatin in the human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 4, D and E).

FIGURE 4.

IFN-γ and TNFα up-regulate Fas expression through pSTAT1 and NF-κB binding to the Fas promoter in human colon carcinoma cells. A, Fas is silenced in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. SW480 and SW620 cells were analyzed for cell surface Fas protein level by flow cytometry (top) and Fas mRNA by semi-quantitative (bottom left) and real-time RT-PCR analysis (bottom right). Gray-filled area, IgG isotype control; solid line, Fas-specific staining. Column, mean; bar, S.D. B, IFN-γ and TNFα cooperate to up-regulate Fas expression in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. SW620 cells were treated with IFN-γ, TNFα, or both IFN-γ and TNFα and stained with Fas-specific mAb for cell surface Fas level. Gray-filled area, IgG isotype control staining; solid line, Fas-specific staining. C, FAS promoter structure. The number below the bar indicates nucleotide number relative to the FAS transcription initiation site. The ChIP PCR regions are indicated above the bar. The GAS and NF-κB-binding consensus sequence elements are also indicated. D, ChIP assays of pSTAT1 association with the FAS promoter (top). SW620 cells were either untreated or treated with IFN-γ for 4 h and used for ChIP. PCR amplification was conducted with FAS promoter sequence-specific primers as shown in C. The primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 2. Bottom, EMSA of pSTAT1 binding to the GAS elements of the human FAS promoter. Probe 1, GAS1; Probe 2, GAS 2, as in C. The probe sequences are listed in supplemental Table 2. E, NF-κB binds to the FAS promoter DNA. SW620 cells were either untreated or treated with TNFα for 30 min. ChIP assays of canonical NF-κB association with the FAS promoter (top) were performed to determine the protein-DNA interactions with p50-specific antibody. IgG was used as antibody negative control. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was used as a PCR positive control. Bottom, EMSA of NF-κB binding to the NF-κB consensus sequence (C) of the human FAS promoter. The probes correspond to the NF-κB consensus sequences as listed in C and are listed in supplemental Table 2. P, positive control NF-κB probe (Santa Cruz).

Analysis of the human FAS promoter region with MacVector identified two potential pSTAT1 binding consensus γ activation site (GAS) elements and at least five potential NF-κB-binding consensus sequences (Fig. 4C). We next performed EMSA and observed that pSTAT1 binds to both GAS elements (Fig. 4D). EMSA also showed that canonical NF-κB binds to all five NF-κB consensus sequences at the FAS promoter region in human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 4E). In summary, our data demonstrated that pSTAT1 and NF-κB directly bind to the FAS promoter in human colon carcinoma cells, and we have mapped the precise binding sites in the human FAS promoter region.

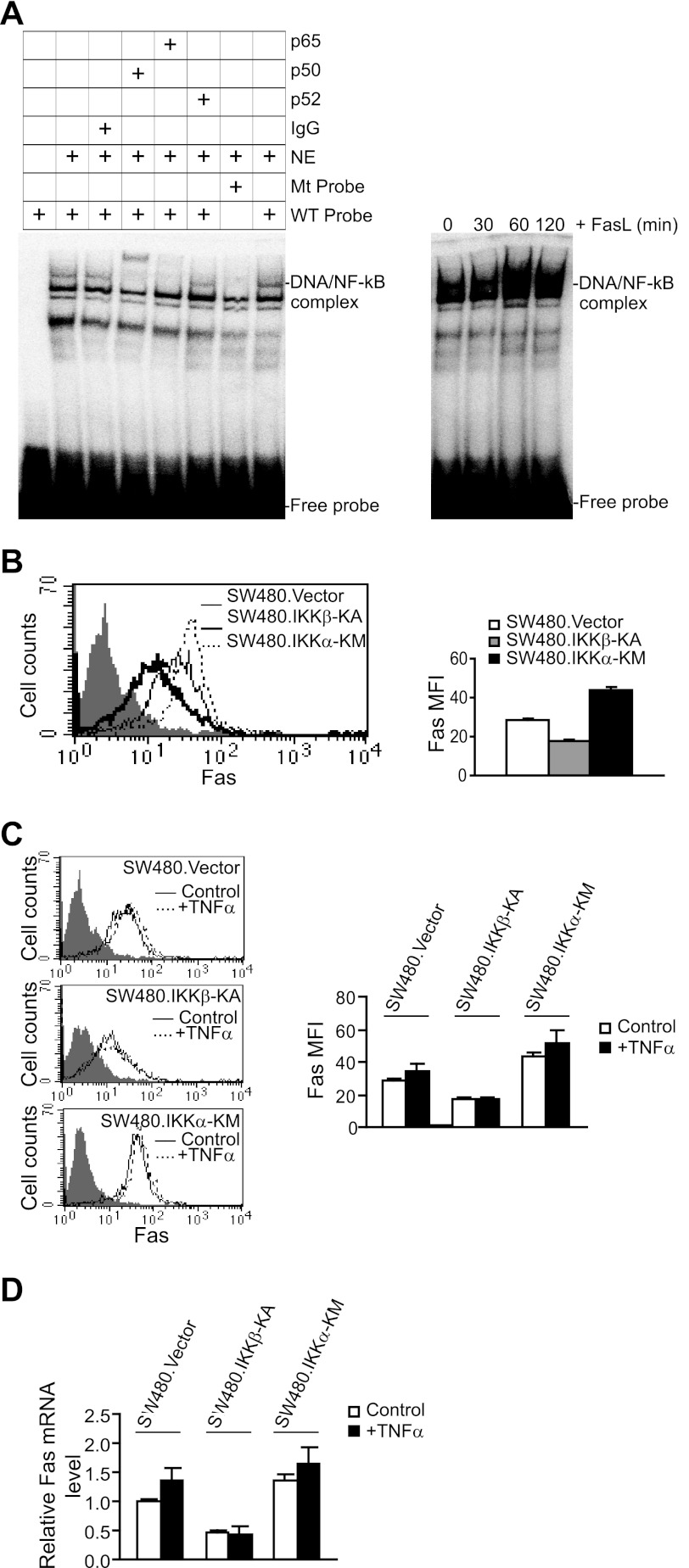

NF-κB Regulates FAS Transcription in Human Colon Carcinoma Cells

TNFα is a potent NF-κB inducer. The above observations that TNFα up-regulates Fas expression suggest that NF-κB might activate Fas expression. To test this hypothesis, Fas-high SW480 cells were stably transfected with the dominant negative IKKβ mutant (IKKβ-KA) to block the canonical NF-κB pathway. EMSA revealed that canonical NF-κB is activated in SW480 cells, and FasL enhances canonical NF-κB activation (Fig. 5A). Flow cytometry analysis indicated that blocking canonical NF-κB activation significantly decreases Fas protein level on the cell surface (Fig. 5B) and Fas mRNA level in the cells (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, blocking canonical NF-κB activation also inhibited tumor cell response to TNFα to activate Fas (Fig. 5, C and D). In contrast, blocking alternate NF-κB activation with the dominant negative IKKα mutant (IKKα-KM) increased cell surface Fas protein level (Fig. 5B) and Fas mRNA level (Fig. 5D) in human colon carcinoma cells. In addition, blocking alternate NF-κB activation does not alter tumor cell response to TNFα to activate Fas (Fig. 5, C and D). Together, these data suggest that canonical NF-κB is a FAS transcription activator and alternate NF-κB is a FAS transcription repressor.

FIGURE 5.

NF-κB is a Fas transcription activator in human colon carcinoma cells. A, FasL induces NF-κB activation in human colon carcinoma cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from SW480 cells and analyzed for NF-κB activity using EMSA with NF-κB consensus sequence-containing DNA probes. Anti-p65 and anti-p50 antibodies were used to identify the canonical NF-κB-probe binding (left). Mutant probe was used as a negative control. Nuclear extracts were also prepared from SW480 cells treated with FasL for the indicated time and analyzed for NF-κB activation using EMSA (right). B, blocking NF-κB activation diminishes Fas expression in human colon carcinoma cells. SW480 cells were stably transfected with control vector, an IKKβ dominant negative mutant (IKKβ-KA), or an IKKα dominant negative mutant (IKKα-KM) and analyzed for Fas protein level on the cell surface. Gray-filled area, IgG isotype control staining; solid thin line, Fas level in SW480. In vector cells, the solid bold line shows Fas protein level in SW480.IKKβ-KA cells, and the dotted thin line shows Fas protein level in SW480.IKKα-KM cells. The Fas MFI was quantified and is presented in the right panel. Columns, mean; error bars, S.D. C and D, blocking canonical NF-κB activation results in loss of response of tumor cells to TNFα-mediated Fas up-regulation. SW480.Vector, SW480.IKKβ-KA, and SW480.IKKα-KM cells were treated with TNFα and analyzed for Fas protein level on the cell surface (C) and mRNA level by real-time RT-PCR (D). Gray-filled area, isotype control staining; solid line, untreated cells; dotted line, TNFα-treated cells. The Fas MFI was quantified and is presented in the right panel. Columns, mean; bars, S.D. For real-time RT-PCR analysis of the Fas mRNA level, the relative Fas mRNA level in SW480.Vector cells was set at 1.

NF-κB Is Also a Fas Transcription Activator in MEF Cells

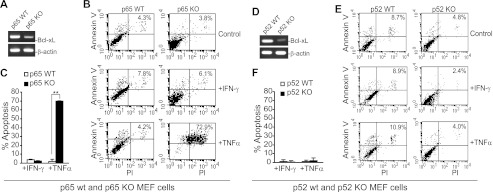

The above observation is a surprising one because canonical NF-κB is often considered a tumor promoter (20, 48, 49), and we showed here that canonical NF-κB is a FAS transcription activator. To determine whether this is a general phenomenon, we examined Fas level in WT and p65 KO MEF cells. It is known that knocking down p65 diminishes Bcl-xL expression and sensitizes MEF cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis (50). It has also been shown that inhibition of NF-κB activity strongly enhances TNFα-mediated apoptosis (28). Indeed, p65 KO MEF cells have decreased Bcl-xL level (Fig. 6A) and increased sensitivity to TNFα-induced apoptosis (Fig. 6, B and C). However, although knocking out p52 also down-regulated Bcl-xL (Fig. 6D), in contrast to p65 KO MEF cells, p52 KO MEF cells exhibited no increased sensitivity to TNFα-induced apoptosis as compared with their matched p52 WT MEF cells (Fig. 6, E and F).

FIGURE 6.

Sensitivity of WT and NF-κB KO MEF cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. A–C, p65 WT and p65 KO MEF cells. A, RT-PCR analysis of Bcl-xL mRNA level. B, cells were cultured in the absence or presence of IFN-γ or TNFα overnight, stained with Annexin V and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The number in each box indicates percentage of Annexin V- and PI-double positive cells. C, quantification of apoptotic cell death. Percentage apoptosis was calculated as the percentage of Annexin V- and PI-positive cells in the presence of IFN-γ or TNFα minus the percentage of Annexin V and PI positive in the absence of IFN-γ or TNFα. Columns, mean; bars, S.D. D–F, p52 WT and p52 KO MEF cells. D, RT-PCR analysis of Bcl-xL mRNA level. E, cells were cultured in the absence or presence of IFN-γ or TNFα and analyzed for apoptosis as in B. F, quantification of apoptotic cell death as in C.

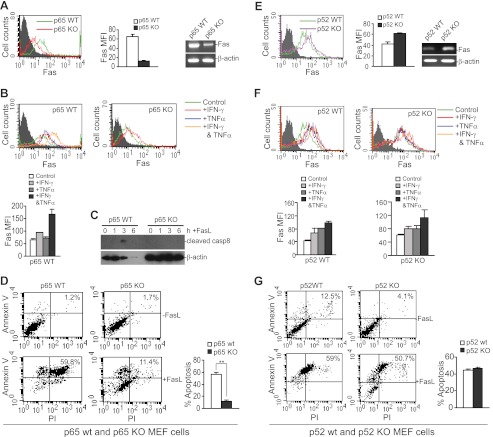

Next, we analyzed p65 and p52 MEF cells to FasL-induced apoptosis. Consistent with what was observed in human colon carcinoma cells, we observed that both Fas protein level and mRNA level are dramatically lower in p65 KO MEF cells as compared with p65 WT MEF cells (Fig. 7A). Like the human colon carcinoma cells, the p65 WT MEF cells are responsive to IFN-γ and TNFα to up-regulate Fas expression (Fig. 7B). The p65 KO MEF cells are also responsive to IFN-γ to up-regulate Fas (Fig. 7B), but due to massive cell death after exposure to TNFα (Fig. 6B), p65 KO MEF cells could not be analyzed for Fas expression level after TNFα treatment. FasL induced caspase 8 activation (Fig. 7C) and apoptosis in the WT MEF cells (Fig. 7D). Consistent with diminished Fas expression, p65 KO MEF cells failed to respond to FasL to activate caspase 8 (Fig. 7C) and acquired a resistant phenotype to FasL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 7.

Canonical NF-κB is a Fas transcription activator, and alternate NF-κB is a Fas transcription repressor in MEF cells. A–D, p65 WT and p65 KO MEF cells. A, cell surface Fas protein (left) and mRNA (right) levels. Gray-filed area, IgG isotype control staining. The Fas MFI was quantified and is presented in the middle panel. Columns, mean; bars, S.D. B, responses of WT and p65 KO MEF cells to IFN-γ and TNFα in Fas up-regulation. WT and p65 KO MEF cells were treated with IFN-γ, TNFα, or both IFN-γ and TNFα and analyzed for Fas protein level as in A. Gray-filled area, isotype control staining. The Fas protein staining levels in cells of various treatments are represented by colored lines as indicated. The Fas MFI of WT MEF cells as shown in the top panel was quantified and is presented in the bottom panel. C, caspase 8 activation in WT and p65 KO MEF cells. Cells were treated with FasL for the indicated times, and cytosol fractions were prepared for the Western blotting analysis of cleaved caspase 8. D, sensitivity of WT and p65 KO MEF cells to FasL-induced apoptosis. Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of FasL overnight and stained with Annexin V and PI. The percentage of FasL-induced cell death was calculated as the percentage of Annexin- and PI-positive cells in the presence of FasL (+FasL) minus the percentage that were Annexin V- and PI-positive in the absence of FasL (−FasL) and is presented in the right panel. Column, mean; bar, S.D. E–G, p52 WT and p52 KO MEF cells. E, cell surface Fas protein (left) and mRNA (right) levels. Gray-filed area, IgG isotype control staining. The Fas MFI was quantified and is presented in the middle panel. Columns, mean; bars, S.D. F, responses of WT and p52 KO MEF cells to IFN-γ and TNFα in Fas up-regulation. Cells were treated with IFN-γ, TNFα, or both IFN-γ and TNFα and analyzed for Fas protein level. Gray-filled area, isotype control staining. The Fas protein staining levels in cells of various treatments were represented by colored lines as indicated. The Fas MFI of WT and p21 KO MEF cells as shown in the top panel was quantified and is presented in the bottom panel. Columns, mean; bars, S.D. G, sensitivity of WT and p52 KO MEF cells to FasL-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis was analyzed as in D.

In contrast to p65 KO cells, p52 KO MEF cells exhibited increased cell surface Fas protein and mRNA level as compared with the matched p52 WT MEF cells (Fig. 7E). Both p52 WT and p52 KO MEF cells responded to IFN-γ and TNFα to up-regulate Fas expression (Fig. 7F). Furthermore, both p52 WT and p52 KO MEF cells are highly sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7G). In summary, our data indicate that 1) canonical NF-κB, but not alternate NF-κB, protects MEF cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis; and 2) canonical NF-κB is a general Fas transcription activator, and alternative NF-κB is a Fas transcription repressor.

DISCUSSION

Although extensive data have shown that Fas functions as a tumor suppressor in both human and mouse tumor models (7, 10–13, 15, 51–57), the role of Fas as a tumor promoter has also been reported, and blocking Fas activity for cancer therapy has been proposed (19). The apparently contrasting observations might be due to the mouse tumor models and cells used in the studies. Fas is a cell surface receptor, and it alone does not generate cellular signaling. It is the FasL that binds to Fas to initiate the Fas-mediated signaling pathways. It has been proposed that membrane-bound FasL only induces Fas-mediated apoptosis, whereas sFasL triggers non-apoptotic signaling pathways (19, 42). Membrane-bound FasL is primarily expressed on activated lymphocytes. Therefore, activation and infiltration of tumor-specific lymphocytes, primarily tumor-specific CD8+ CTLs in the tumor microenvironment, might be essential for Fas function. If the tumors are non-immunogenic or immune suppressive, tumor-specific immune cells may then not be activated to infiltrate into the tumor microenvironment. Studies have shown that human colorectal tumors are immunogenic (43, 44), whereas MCA-induced sarcoma is highly immunogenic (30), Using these immunogenic spontaneous colon carcinoma and sarcoma mouse models, we demonstrated here that Fas functions as a suppressor of tumor development under physiological conditions.

Our finding that Fas functions as a tumor suppressor is further supported by our data from human colorectal cancer specimens. We demonstrated that patients with high Fas protein levels in their tumor cells have a longer time before recurrence occurs when tumor-infiltrating CTL levels are low in their tumors (Fig. 2). It is known that the perforin-dependent cytotoxicity is the dominant anti-tumor cytotoxic effector mechanism (58); therefore, the perforin cytotoxicity alone might be sufficient to suppress tumor development when CTL level is high (51). Our data suggest that in the tumor microenvironment with limited CTL infiltration, Fas-mediated tumor cell apoptosis might play a critical role in CTL-mediated tumor suppression in human colorectal cancer.

Constitutive NF-κB activation often promotes oncogenesis, providing a strong rationale for anticancer strategies that inhibit NF-κB signaling (48, 49). Indeed, as reported in the literature and observed in this study, canonical NF-κB protects MEF cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis (28, 50) (Fig. 6). However, we observed that canonical NF-κB functions in an opposing way in mediating FasL-induced apoptosis. Thus, our finding revealed that canonical NF-κB is a general Fas transcription activator to promote Fas-mediated apoptosis. Therefore, in contexts where prosurvival signals derive from other oncogenes, canonical NF-κB activity might instead promote apoptosis (47, 59, 60). Our finding is consistent in principle with recent observations that NF-κB signaling enhances tumor cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis and to cytotoxic chemotherapy, thereby exerting a tumor-suppressor function (23–28).

Our observation that alternate NF-κB is a Fas transcription repressor in both human colon carcinoma cells and MEF cells is an interesting one (Figs. 5 and 7). Alternate NF-κB is often sequentially activated after the canonical NF-κB (61). Therefore, it is possible that alternate NF-κB might function as a Fas transcription repressor to turn off canonical NF-κB-activated Fas transcription to prevent sustained Fas transcription activation. Our initial study did not identify direct interaction between alternate NF-κB interaction and the Fas promoter in human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 5A). Therefore, determination of how alternative NF-κB represses Fas transcription requires further study. Nevertheless, our data suggest that a therapeutic strategy to inhibit NF-κB signaling should take into consideration that such inhibition may confer tumor cell resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis, thereby suppressing the Fas-mediated apoptosis of the host cancer immune surveillance system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kimberly Smith for excellent technical assistance in immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissues. We also thank Drs. Butcher and Lars Damstrup for providing Mega-FasL.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA133085 (to K. L.). This work was also supported by American Cancer Society Grant RSG-09-209-01-TBG (to K. L.) and the Siyuan Foundation (to F. L.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables 1 and 2.

- MCA

- 3-methylcholanthrene

- AOM

- azoxymethane

- DSS

- dextran sodium sulfate

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PI

- propidium iodide

- MEF

- mouse embryo fibroblast

- GAS

- γ activation site

- CTL

- cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lavrik I. N., Krammer P. H. (2012) Regulation of CD95/Fas signaling at the DISC. Cell Death Differ. 19, 36–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaufmann T., Strasser A., Jost P. J. (2012) Fas death receptor signaling. Roles of Bid and XIAP. Cell Death Differ. 19, 42–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kober A. M., Legewie S., Pforr C., Fricker N., Eils R., Krammer P. H., Lavrik I. N. (2011) Caspase-8 activity has an essential role in CD95/Fas-mediated MAPK activation. Cell Death Dis. 2, e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Straus S. E., Jaffe E. S., Puck J. M., Dale J. K., Elkon K. B., Rösen-Wolff A., Peters A. M., Sneller M. C., Hallahan C. W., Wang J., Fischer R. E., Jackson C. M., Lin A. Y., Bäumler C., Siegert E., Marx A., Vaishnaw A. K., Grodzicky T., Fleisher T. A., Lenardo M. J. (2001) The development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with germ line Fas mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood 98, 194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nikolov N. P., Shimizu M., Cleland S., Bailey D., Aoki J., Strom T., Schwartzberg P. L., Candotti F., Siegel R. M. (2010) Systemic autoimmunity and defective Fas ligand secretion in the absence of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Blood 116, 740–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lenardo M. J., Oliveira J. B., Zheng L., Rao V. K. (2010) ALPS. Ten lessons from an international workshop on a genetic disease of apoptosis. Immunity 32, 291–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neven B., Magerus-Chatinet A., Florkin B., Gobert D., Lambotte O., De Somer L., Lanzarotti N., Stolzenberg M. C., Bader-Meunier B., Aladjidi N., Chantrain C., Bertrand Y., Jeziorski E., Leverger G., Michel G., Suarez F., Oksenhendler E., Hermine O., Blanche S., Picard C., Fischer A., Rieux-Laucat F. (2011) A survey of 90 patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome related to TNFRSF6 mutation. Blood 118, 4798–4807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dowdell K. C., Niemela J. E., Price S., Davis J., Hornung R. L., Oliveira J. B., Puck J. M., Jaffe E. S., Pittaluga S., Cohen J. I., Fleisher T. A., Rao V. K. (2010) Somatic FAS mutations are common in patients with genetically undefined autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Blood 115, 5164–5169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park W. S., Oh R. R., Kim Y. S., Park J. Y., Lee S. H., Shin M. S., Kim S. Y., Kim P. J., Lee H. K., Yoo N. Y., Lee J. Y. (2001) Somatic mutations in the death domain of the Fas (Apo-1/CD95) gene in gastric cancer. J. Pathol. 193, 162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lei D., Sturgis E. M., Wang L. E., Liu Z., Zafereo M. E., Wei Q., Li G. (2010) FAS and FASLG genetic variants and risk for second primary malignancy in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 19, 1484–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang M., Sun T., Wang L., Yu D., Zhang X., Miao X., Liu J., Zhao D., Li H., Tan W., Lin D. (2008) Functional variants in cell death pathway genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 3230–3236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Qiu L. X., Shi J., Yuan H., Jiang X., Xue K., Pan H. F., Li J., Zheng M. H. (2009) FAS −1,377 G/A polymorphism is associated with cancer susceptibility. Evidence from 10,564 cases and 12,075 controls. Hum. Genet. 125, 431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sunter N. J., Scott K., Hills R., Grimwade D., Taylor S., Worrillow L. J., Fordham S. E., Forster V. J., Jackson G., Bomken S., Jones G., Allan J. M. (2012) A functional variant in the core promoter of the CD95 cell death receptor gene predicts prognosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 119, 196–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sibley K., Rollinson S., Allan J. M., Smith A. G., Law G. R., Roddam P. L., Skibola C. F., Smith M. T., Morgan G. J. (2003) Functional FAS promoter polymorphisms are associated with increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 63, 4327–4330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sung W. W., Wang Y. C., Cheng Y. W., Lee M. C., Yeh K. T., Wang L., Wang J., Chen C. Y., Lee H. (2011) A polymorphic −844T/C in FasL promoter predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 5991–5999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnhart B. C., Legembre P., Pietras E., Bubici C., Franzoso G., Peter M. E. (2004) CD95 ligand induces motility and invasiveness of apoptosis-resistant tumor cells. EMBO J. 23, 3175–3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peter M. E., Budd R. C., Desbarats J., Hedrick S. M., Hueber A. O., Newell M. K., Owen L. B., Pope R. M., Tschopp J., Wajant H., Wallach D., Wiltrout R. H., Zörnig M., Lynch D. H. (2007) The CD95 receptor. Apoptosis revisited. Cell 129, 447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kleber S., Sancho-Martinez I., Wiestler B., Beisel A., Gieffers C., Hill O., Thiemann M., Mueller W., Sykora J., Kuhn A., Schreglmann N., Letellier E., Zuliani C., Klussmann S., Teodorczyk M., Gröne H. J., Ganten T. M., Sültmann H., Tüttenberg J., von Deimling A., Regnier-Vigouroux A., Herold-Mende C., Martin-Villalba A. (2008) Yes and PI3K bind CD95 to signal invasion of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 13, 235–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen L., Park S. M., Tumanov A. V., Hau A., Sawada K., Feig C., Turner J. R., Fu Y. X., Romero I. L., Lengyel E., Peter M. E. (2010) CD95 promotes tumor growth. Nature 465, 492–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karin M. (2006) Nuclear factor-κB in cancer development and progression. Nature 441, 431–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karl S., Pritschow Y., Volcic M., Häcker S., Baumann B., Wiesmüller L., Debatin K. M., Fulda S. (2009) Identification of a novel proapopotic function of NF-κB in the DNA damage response. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13, 4239–4256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen F., Castranova V. (2007) Nuclear factor-κB, an unappreciated tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 67, 11093–11098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vince J. E., Wong W. W., Khan N., Feltham R., Chau D., Ahmed A. U., Benetatos C. A., Chunduru S. K., Condon S. M., McKinlay M., Brink R., Leverkus M., Tergaonkar V., Schneider P., Callus B. A., Koentgen F., Vaux D. L., Silke J. (2007) IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFα-dependent apoptosis. Cell 131, 682–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varfolomeev E., Blankenship J. W., Wayson S. M., Fedorova A. V., Kayagaki N., Garg P., Zobel K., Dynek J. N., Elliott L. O., Wallweber H. J., Flygare J. A., Fairbrother W. J., Deshayes K., Dixit V. M., Vucic D. (2007) IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-κB activation, and TNFα-dependent apoptosis. Cell 131, 669–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen S. L., Wang L., Yalcin-Chin A., Li L., Peyton M., Minna J., Harran P., Wang X. (2007) Autocrine TNFα signaling renders human cancer cells susceptible to Smac-mimetic-induced apoptosis. Cancer Cell 12, 445–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chien Y., Scuoppo C., Wang X., Fang X., Balgley B., Bolden J. E., Premsrirut P., Luo W., Chicas A., Lee C. S., Kogan S. C., Lowe S. W. (2011) Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-{kappa}B promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev. 25, 2125–2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jing H., Kase J., Dörr J. R., Milanovic M., Lenze D., Grau M., Beuster G., Ji S., Reimann M., Lenz P., Hummel M., Dörken B., Lenz G., Scheidereit C., Schmitt C. A., Lee S. (2011) Opposing roles of NF-κB in anti-cancer treatment outcome unveiled by cross-species investigations. Genes Dev. 25, 2137–2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jennewein C., Karl S., Baumann B., Micheau O., Debatin K. M., Fulda S. (2012) Identification of a novel proapoptotic role of NF-κB in the regulation of TRAIL- and CD95-mediated apoptosis of glioblastoma cells. Oncogene 31, 1468–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crescenzi E., Pacifico F., Lavorgna A., De Palma R., D'Aiuto E., Palumbo G., Formisano S., Leonardi A. (2011) NF-κB-dependent cytokine secretion controls Fas expression on chemotherapy-induced premature senescent tumor cells. Oncogene 30, 2707–2717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shankaran V., Ikeda H., Bruce A. T., White J. M., Swanson P. E., Old L. J., Schreiber R. D. (2001) IFNγ and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumor immunogenicity. Nature 410, 1107–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greten F. R., Eckmann L., Greten T. F., Park J. M., Li Z. W., Egan L. J., Kagnoff M. F., Karin M. (2004) IKKβ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell 118, 285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ryan K. M., Ernst M. K., Rice N. R., Vousden K. H. (2000) Role of NF-κB in p53-mediated programmed cell death. Nature 404, 892–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kew R. R., Penzo M., Habiel D. M., Marcu K. B. (2012) The IKKα-dependent NF-κB p52/RelB noncanonical pathway is essential to sustain a CXCL12 autocrine loop in cells migrating in response to HMGB1. J. Immunol. 188, 2380–2386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Mahony A., Lin X., Geleziunas R., Greene W. C. (2000) Activation of the heterodimeric IκB kinase α (IKKα)-IKKβ complex is directional. IKKα regulates IKKβ under both basal and stimulated conditions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1170–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu F., Hu X., Zimmerman M., Waller J. L., Wu P., Hayes-Jordan A., Lev D., Liu K. (2011) TNFα Cooperates with IFN-γ to Repress Bcl-xL Expression to Sensitize Metastatic Colon Carcinoma Cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. PLoS One 6, e16241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zimmerman M., Yang D., Hu X., Liu F., Singh N., Browning D., Ganapathy V., Chandler P., Choubey D., Abrams S. I., Liu K. (2010) IFN-γ up-regulates survivin and Ifi202 expression to induce survival and proliferation of tumor-specific T cells. PLoS One 5, e14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu X., Yang D., Zimmerman M., Liu F., Yang J., Kannan S., Burchert A., Szulc Z., Bielawska A., Ozato K., Bhalla K., Liu K. (2011) IRF8 regulates acid ceramidase expression to mediate apoptosis and suppresses myelogeneous leukemia. Cancer Res. 71, 2882–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang D., Wang S., Brooks C., Dong Z., Schoenlein P. V., Kumar V., Ouyang X., Xiong H., Lahat G., Hayes-Jordan A., Lazar A., Pollock R., Lev D., Liu K. (2009) IFN regulatory factor 8 sensitizes soft tissue sarcoma cells to death receptor-initiated apoptosis via repression of FLICE-like protein expression. Cancer Res. 69, 1080–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wingender G., Krebs P., Beutler B., Kronenberg M. (2010) Antigen-specific cytotoxicity by invariant NKT cells in vivo is CD95/CD178-dependent and is correlated with antigenic potency. J. Immunol. 185, 2721–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shanker A., Brooks A. D., Jacobsen K. M., Wine J. W., Wiltrout R. H., Yagita H., Sayers T. J. (2009) Antigen presented by tumors in vivo determines the nature of CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 69, 6615–6623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krammer P. H. (1999) CD95(APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis. Live and let die. Adv. Immunol. 71, 163–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Reilly L. A., Tai L., Lee L., Kruse E. A., Grabow S., Fairlie W. D., Haynes N. M., Tarlinton D. M., Zhang J. G., Belz G. T., Smyth M. J., Bouillet P., Robb L., Strasser A. (2009) Membrane-bound Fas ligand only is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Nature 461, 659–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Camus M., Tosolini M., Mlecnik B., Pagès F., Kirilovsky A., Berger A., Costes A., Bindea G., Charoentong P., Bruneval P., Trajanoski Z., Fridman W. H., Galon J. (2009) Coordination of intratumoral immune reaction and human colorectal cancer recurrence. Cancer Res. 69, 2685–2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galon J., Costes A., Sanchez-Cabo F., Kirilovsky A., Mlecnik B., Lagorce-Pagès C., Tosolini M., Camus M., Berger A., Wind P., Zinzindohoué F., Bruneval P., Cugnenc P. H., Trajanoski Z., Fridman W. H., Pagès F. (2006) Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 313, 1960–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krammer P. H., Galle P. R., Möller P., Debatin K. M. (1998) CD95(APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis in normal and malignant liver, colon, and hematopoietic cells. Adv. Cancer Res. 75, 251–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ahn E. Y., Pan G., Vickers S. M., McDonald J. M. (2002) IFN-gammaupregulates apoptosis-related molecules and enhances Fas-mediated apoptosis in human cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 100, 445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zheng Y., Ouaaz F., Bruzzo P., Singh V., Gerondakis S., Beg A. A. (2001) NF-κB RelA (p65) is essential for TNF-α-induced Fas expression but dispensable for both TCR-induced expression and activation-induced cell death. J. Immunol. 166, 4949–4957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Staudt L. M. (2010) Oncogenic activation of NF-κB. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ben-Neriah Y., Karin M. (2011) Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-κB as the matchmaker. Nat. Immunol. 12, 715–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deng Y., Ren X., Yang L., Lin Y., Wu X. (2003) A JNK-dependent pathway is required for TNFα-induced apoptosis. Cell 115, 61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Caldwell S. A., Ryan M. H., McDuffie E., Abrams S. I. (2003) The Fas/Fas ligand pathway is important for optimal tumor regression in a mouse model of CTL adoptive immunotherapy of experimental CMS4 lung metastases. J. Immunol. 171, 2402–2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sträter J., Hinz U., Hasel C., Bhanot U., Mechtersheimer G., Lehnert T., Möller P. (2005) Impaired CD95 expression predisposes for recurrence in curatively resected colon carcinoma. Clinical evidence for immunoselection and CD95L-mediated control of minimal residual disease. Gut 54, 661–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schillaci R., Salatino M., Cassataro J., Proietti C. J., Giambartolomei G. H., Rivas M. A., Carnevale R. P., Charreau E. H., Elizalde P. V. (2006) Immunization with murine breast cancer cells treated with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides to type I insulin-like growth factor receptor induced an antitumoral effect mediated by a CD8+ response involving Fas/Fas ligand cytotoxic pathway. J. Immunol. 176, 3426–3437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ikner A., Ashkenazi A. (2011) TWEAK induces apoptosis through a death-signaling complex comprising receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), Fas-associated death domain (FADD), and caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21546–21554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Owen-Schaub L. B., van Golen K. L., Hill L. L., Price J. E. (1998) Fas and Fas ligand interactions suppress melanoma lung metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 188, 1717–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guillen-Ahlers H., Suckow M. A., Castellino F. J., Ploplis V. A. (2010) Fas/CD95 deficiency in ApcMin/+ mice increases intestinal tumor burden. PLoS One 5, e9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ruiz-Ruiz C., Robledo G., Cano E., Redondo J. M., Lopez-Rivas A. (2003) Characterization of p53-mediated up-regulation of CD95 gene expression upon genotoxic treatment in human breast tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31667–31675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kägi D., Ledermann B., Bürki K., Seiler P., Odermatt B., Olsen K. J., Podack E. R., Zinkernagel R. M., Hengartner H. (1994) Cytotoxicity mediated by T cells and natural killer cells is greatly impaired in perforin-deficient mice. Nature 369, 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Klein U., Ghosh S. (2011) The two faces of NF-κB signaling in cancer development and therapy. Cancer Cell 20, 556–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bivona T. G., Hieronymus H., Parker J., Chang K., Taron M., Rosell R., Moonsamy P., Dahlman K., Miller V. A., Costa C., Hannon G., Sawyers C. L. (2011) FAS and NF-κB signaling modulate dependence of lung cancers on mutant EGFR. Nature 471, 523–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bista P., Zeng W., Ryan S., Bailly V., Browning J. L., Lukashev M. E. (2010) TRAF3 controls activation of the canonical and alternative NFκB by the lymphotoxin β receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12971–12978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.