Background: Adrenergic activation of brown adipocytes mobilizes fatty acids for oxidation and promotes transcription of oxidative genes.

Results: Activation of adipocyte lipases generates agonists of PPARα and PPARδ that promote transcription of oxidative genes.

Conclusion: Lipolytic products signal via PPARα and PPARδ.

Significance: Lipolytic activation of PPARα and PPARδ provides a mechanism for matching oxidative capacity to substrate supply.

Keywords: β-Oxidation, Fatty Acid, Lipase, Lipolysis, Mitochondria, Nuclear Receptors, Fluorescence Imaging, Thermogenesis

Abstract

β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) promote brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis by mobilizing fatty acids and inducing the expression of oxidative genes. β-AR activation increases the expression of oxidative genes by elevating cAMP, but whether lipolytic products can modulate gene expression is not known. This study examined the role that adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) plays in the induction of gene expression. Activation of brown adipocytes by β-AR agonism or 8-bromo-cyclic AMP increased the expression of PGC1α, PDK4, PPARα, uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), and neuron-derived orphan receptor-1 (NOR-1), and concurrent inhibition of HSL reduced the induction of PGC1α, PDK4, PPARα, and UCP1 but not NOR-1. Similar results were observed in the BAT of mice following pharmacological or genetic inhibition of HSL and in brown adipocytes with stable knockdown of ATGL. Conversely, treatments that increase endogenous fatty acids elevated the expression of oxidative genes. Pharmacological antagonism and siRNA knockdown indicate that PPARα and PPARδ modulate the induction of oxidative genes by β-AR agonism. Using a live cell fluorescent reporter assay of PPAR activation, we demonstrated that ligands for PPARα and -δ, but not PPARγ, were rapidly generated at the lipid droplet surface and could transcriptionally activate PPARα and -δ. Knockdown of ATGL reduced cAMP-mediated induction of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation. Consequently, ATGL knockdown reduced maximal oxidation of fatty acids, but not pyruvate, in response to cAMP stimulation. Overall, the results indicate that lipolytic products can activate PPARα and PPARδ in brown adipocytes, thereby expanding the oxidative capacity to match enhanced fatty acid supply.

Introduction

Brown adipose tissue (BAT)3 is a thermogenic organ that functions to maintain body temperature by producing heat in response to cold exposure. BAT is activated by sympathetic nerves that release catecholamines and stimulate β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs). β-AR activation of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway elevates intracellular fatty acids which activate UCP1 (the molecular mechanism of thermogenesis) and supplies fuel for high rates of oxidative metabolism. Activation of β-ARs on brown adipocytes also promotes the transcription of genes involved in thermogenesis, such as UCP1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC1α), a key transcriptional co-activator (1–3) that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism. Exactly how β-ARs induce the expression of these genes is not entirely known, but PKA phosphorylates the transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) (4, 5), thereby activating transcription of genes such as PGC1α and UCP1, which contain cAMP response elements (6). In addition, the genes for UCP1 and PGC1α contain binding sites for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), a family of nuclear receptors that are involved in lipid signaling. Whether PPARs are important in mediating the action of β-AR activation is not known.

β-AR activation of lipolysis and gene transcription are generally thought to be parallel pathways in brown adipocytes. PKA triggers lipolysis by indirectly activating adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) (7) and by directly phosphorylating and activating hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), which acts on triacylglycerol and diacylglycerol (8). Work from our laboratory and others has led to the appreciation that lipolysis can alter the expression patterns of genes involved in both inflammation and oxidation (9–12). In white adipose tissue (WAT), acute activation of lipolysis suppresses PKA activation and induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines (10) that limit excessive fatty acid production (9, 13). In contrast, chronic activation of β-ARs in WAT produces a catabolic remodeling marked by the appearance of multilocular adipocytes and increased in situ fat oxidation, thereby resembling a BAT-like phenotype (14). This “browning” of white fat is delayed in mice lacking HSL (11) and in mice lacking the nuclear receptor PPARα, suggesting that lipolysis might signal via PPARs (15). Recent evidence has also implicated the other major lipase of BAT, ATGL, in regulating the expression of catabolic genes. Mice lacking ATGL in adipose tissue have reduced expression of PPARα target genes in BAT (16), and ATGL is needed to maintain an oxidative phenotype in the heart, likely via activation of PPARα (12). Although these studies suggest that ATGL and HSL signal through PPARs, chronic loss of lipase function may indirectly alter PPAR activity. Furthermore, these studies did not address how and where the acute activation of lipases might regulate gene transcription via PPARs.

The nuclear receptors PPARα, PPARδ, and PPARγ are activated by various lipid species and regulate different aspects of lipid metabolism, such as fatty acid oxidation and lipid storage (17). Although the therapeutic benefits of targeting the PPARs are widely known (18), how these receptors are activated in a biological context and the cellular site(s) of ligand production are less well understood. Here we demonstrate that lipolysis is required for the maximal induction of thermogenic genes by β-AR activation in brown adipocytes. Increasing fatty acid levels promoted the transcription of genes involved in thermogenesis, and both PPARα and PPARδ were required for the maximal induction of thermogenic genes by β-AR. Furthermore, we demonstrate that ligands for both PPARα and -δ, but not PPARγ, are created at the lipid droplet surface within minutes of stimulation with 8-Br-cAMP and can transcriptionally activate PPARα and -δ over a period of hours. Activation of PPARα and -δ was sufficient to increase the expression of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation. ATGL was required for the maximal induction of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial electron transport and the increase of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in response to cAMP stimulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal Studies

C57BL/6J mice (n = 11/group) were treated with the HSL inhibitor BAY 59-9435 (BAY) (30 mg/kg) or methylcellulose followed by the β3-AR agonist CL-316,243 (CL) (10 nmol) for 3 h, as described previously (11). BAT was collected and stored in RNAlater at −80 °C until processed for RNA extraction (11). HSL-KO mice were provided by Frederic Kraemer (Stanford University) and bred and genotyped as described (11). HSL-KO (n = 13/group) and heterozygous (Het) and WT littermates (n = 13/group) were treated with CL for 6 h, and BAT was processed as described above.

Cell Culture Studies

A brown adipocyte cell line was cultured and differentiated as described previously (19). Briefly, confluent cells were placed in induction medium (0.5 mm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 0.25 mm indomethacin, 2 μg/ml dexamethasone, 1 nm T3, 20 nm insulin) for 2 days and subsequently maintained on differentiation medium (1 nm T3, 20 nm insulin). All experiments were performed on cultures at 6–8 days post-induction. Unless otherwise indicated, cells were rinsed with PBS, and medium was changed to Hepes-Krebs-Ringer buffer + 1% BSA. Where indicated, brown adipocytes were pretreated with triacsin C (5 μm, Sigma), BAY (5 μm), etomoxir (50 μm, Sigma), GW6471 (10 μm, Tocris), GSK0660 (2 μm, Tocris), or GW9662 (30 μm, Tocris) followed by isoproterenol (10 μm, Sigma) or 8-Br-cAMP (1 mm, Biolog). For experiments examining mitochondrial gene expression, brown adipocytes were stimulated for 24 h with 8-Br-cAMP (1 mm) or selective agonists of PPARα (GW7647, 1 μm, Tocris), or PPARδ (L-165,041, 5 μm, Tocris). Medium fatty acids were measured as described previously (11). Western blot for ATGL was performed as described previously (9).

Lentivirus Transduction and siRNA Transfections

Undifferentiated brown adipocytes were infected with lentivirus vectors (Open Biosystems) for a control non-targeting shRNA (RHS4346 (shCON)) or one directed against ATGL (RMM4431-98739845 (shATGL)) at a multiplicity of infection of 100 for 24 h and selected by hygromycin (4 μg/ml, GoldBio) and GFP fluorescence by FACS. Cells were differentiated and treated as described above.

Transient siRNA knockdown was performed as described previously (9) with the following modifications. Brown adipocytes cultured 4 days post-induction were trypsizined and replated (2.4 × 105 cells/well) in collagen-coated 24-well plates containing Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and 50 nm SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon) against PPARα (siPPARα; M-040740-01-0005), PPARδ (siPPARδ; M-042751-01-0005), or nontargeting siRNA (siCON; D-001210-01). Experiments were performed 72 h post-transfection on triplicate wells as stated above.

Gene Expression Analysis

RNA isolated from BAT and brown adipocytes was analyzed for gene expression by quantitative PCR (QPCR) as described previously (9, 11). PDK4 cDNA was amplified using primers 5′-AGGATTACTGACCGCCTCTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGTCTGTCCCATAACCTGAC-3′ (reverse); MCAD with 5′-ATTGCCAATCAGCTAGCCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGATAGATCTTGGCGTCCC-3′ (reverse); COXII with 5′-CGAGTCGTTCTGCCAATAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAGAGCATTGGCCATAGAA-3′ (reverse); cytochrome c (Cycs) with 5′-GGAGAAAGGGCAGACCTAAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGTCCAACAAAAACATTGCT-3′ (reverse); and COXIV with 5′-CCCTCATACTTTCGATCGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTATTAGCATGGACCATTGGA-3′ (reverse). mRNA knockdown of PPARα was detected with primers 5′-AGGCTGTAAGGGCTTCTTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGAATTGCATTGTGTGACAT-3′ (reverse) and knockdown of PPARδ with 5′-GACAATCCGCATGAAGCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGATAGCGTTGTGCGACAT-3′(reverse). All other cDNAs were amplified using primers described previously (11, 14, 15).

Generation of Reporter Constructs

The ligand-binding domain of human PPARα (NP_001001928; amino acids (aa) 191–467), mouse PPARα (NP_035274; aa 191–469) PPARδ (NP_035275; aa 162–441), and PPARγ (NP_001120802; aa 207–474) were amplified by PCR. Ligand-binding domains were cloned into AgeI/NotI on the C terminus of full-length Perilipin-1 (Plin1; NP_783571). The LXXLL-containing domain of steroid receptor co-activator 1 (SRC1) (NP_035011; aa 620–770) was amplified from mouse cDNA and cloned in-frame into enhance yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)-C1 (Clontech) vector (EYFP-SRC1). Chimeras for the yeast GAL4 DNA-binding domain were made by fusing the DNA-binding domain of GAL4 (aa 1–147) in-frame with the ligand-binding domain of human PPARα (aa 167–468) or human PPARδ (NP_006229; aa 139–441) into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen).

Reporter Assays

Fluorescent reporter experiments were performed by transfecting brown adipocytes with reporter plasmids for PPARα, PPARδ, or PPARγ and EYFP-SRC1 with Lipofectamine LTX/Plus (Invitrogen), as recommended by the manufacturer. Cultures at 4–5 days post-induction were trypsinized and seeded onto 25-mm coverslips containing a mixture of DNA, LTX/Plus, and DMEM + 10% FBS. Images were acquired as described previously for EYFP fluorescence using a 40 × 0.9 N.A. water immersion lens (20). Images for EYFP and phase were acquired every minute, and the region of interest from an average of two frames was quantified using IPlabs software (Scanalytics). Cells were pretreated with DMSO or BAY for 10 min, and the basal fluorescence was recorded for 4–6 frames followed by stimulation with 8-Br-cAMP (1 mm) for 20 min and finally by the addition of ligands for PPARα (Wy-14,643 (Wy), 100 μm), PPARδ (L-165,041 (L165), 10 μm), or PPARγ (rosiglitazone, 10 μm) for 8–12 min. The data from the region of interest were normalized to the maximum EYFP fluorescence in the region of interest induced by Wy, L165, or rosiglitazone. The effect of oleic acid on fluorescent reporters was tested with 400 μm oleic acid complexed to BSA for 12 min. Data were normalized to the maximal effect induced by full PPAR agonists (intrinsic activity) determined at the end of each experiment. Normalized data from 3–4 independent experiments with 2–4 coverslips/experiment were combined for presentation and statistical analysis. At the end of some experiments, coverslips were stained for neutral lipids with LipidTOX Deep Red (Invitrogen) and imaged with Cy5 excitation/emission filters (20).

Gal4 luciferase reporter assays were performed by transfecting brown adipocytes with 0.7 μg of Gal4-PPARα or Gal4-PPARδ, 0.7 μg of luciferase reporter (pUAS-Luc2; Addgene 24343), and 100 ng of β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter as stated above. Cells were cultured on 12-well collagen-coated plates and used 6–7 days post-differentiation. Transfected cells were treated with BAY or DMSO for 30 min followed by isoproterenol for 8 h and then lysed in 120 μl of cell culture lysis reagent (Promega). Ligands for PPARα (Wy) and PPARδ (L165) were used as positive controls. Luciferase assays were performed as described previously (9).

Measurement of Mitochondrial Respiration

Mitochondrial respiration was measured in digitonin-permeabilized cells using the MitoXpress (Luxcell Biosciences) phosphorescent oxygen-sensitive fluorescent probe (21–23). Probe fluorescence is quenched in the presence of molecular oxygen via a nonchemical (collisional) mechanism and is fully reversible. As cells respire, the change in oxygen consumption is seen as an increase in probe fluorescence and reflects the increase in mitochondrial activity over time (23). shCON or shATGL brown adipocytes were stimulated with 1 mm 8-Br-cAMP for 48 h with medium changed every 24 h. Cells were trypsinized, washed once with PBS/1 mm EDTA followed by PBS/1 mm EDTA/1% BSA, and resuspended in 250 μl of respiration buffer B (modified from Ref. 22; 0.5 mm EGTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 20 mm taurine, 10 mm KH2PO4, 20 mm Hepes, 0.1% BSA, 60 mm KCl, 110 mm mannitol, pH 7.1). Cells were added to duplicate wells in a black, clear-bottom, 96-well plate containing 110 μl of respiration buffer B plus 20 μg/ml digitonin, 100 nm MitoXpress probe, 5 mm malate, and the indicated substrates (5 mm pyruvate or 50 μm palmitoylcarnitine with 2 mm ADP or 10 μm carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP)). The plate was covered with 100 μl of mineral oil to prevent diffusion of ambient oxygen, and wells were read with a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 plate reader in time-resolved mode (30 °C every 1.5 min, with an excitation/emission of 380/650 nm, a delay of 50 μs, and a gate time of 200 μs). No oxygen consumption was observed in cells without substrate or in cells treated with substrate and 1 μm rotenone. The relative oxygen consumption rate was calculated as the maximal linear increase in fluorescence over 4.5 min (SoftMax Pro, Molecular Devices) and normalized to 4 × 105 cells.

Mitochondrial DNA was quantified on brown adipocyte cultures that were stimulated with 8-Br-cAMP as stated above. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol, and QPCR was performed using ABsolute Blue QPCR SYBR Green mix (Thermo Scientific) and primers for Ndfuv1 (nuclear DNA (nDNA)) and COXI (mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)) as described (24).

Statistical Analysis

Data, reported as means ± S.E., were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA with comparisons performed using the Bonferroni post hoc test (GraphPad Software). Comparisons between the two groups were analyzed by an unpaired two-tailed t test.

RESULTS

Lipolysis Is Required for the Maximal Induction of Thermogenic Gene Expression by β-AR in Brown Adipocytes and BAT

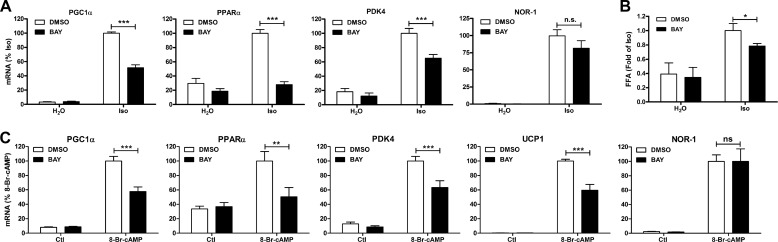

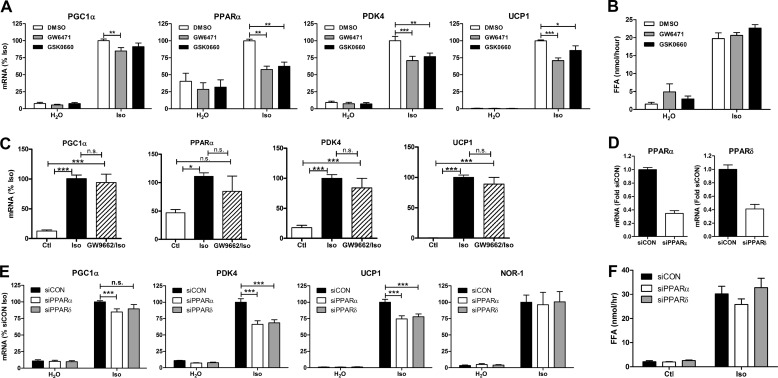

We initially tested the role of lipolysis in modulating the induction of gene expression by β-AR activation in brown adipocytes via pharmacological inhibition of HSL. Treatment of brown adipocytes with the β-AR agonist isoproterenol induced the expression of PGC1α, PPARα, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4), and NOR-1 (Fig. 1A). Inhibition of lipolysis with the selective HSL inhibitor BAY reduced the induction of PGC1α, PPARα, and PDK4 but not NOR-1. BAY did not have any effect on the basal levels of gene expression. As expected, β-AR activation increased lipolysis, an effect that was reduced by BAY (Fig. 1B). To ensure that these effects on gene expression were not due to alterations in β-adrenergic signaling, we bypassed the β-AR by using the cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP. Stimulation of brown adipocytes with 8-Br-cAMP induced the expression of PGC1α, PPARα, PDK4, and UCP1, an effect that was reduced by BAY (Fig. 1C). The induction of NOR-1 mRNA by 8-Br-cAMP was unaffected by BAY. These results suggest that HSL positively regulates the induction of a subset of genes by β-AR activation.

FIGURE 1.

HSL is required for β-AR-mediated induction of oxidative genes in brown adipocytes. A, brown adipocytes were treated with BAY (5 μm) or vehicle (DMSO) followed by vehicle (H2O) or isoproterenol (Iso; 10 μm) for 4 h. mRNA levels were measured by QPCR, normalized to percent peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA), and expressed as percent isoproterenol. B, medium free fatty acids (FFA) were measured after 4 h and expressed as -fold isoproterenol. C, brown adipocytes were treated as described in A, except cells were stimulated with 8-Br-cAMP (1 mm). Data are from 3–4 independent experiments performed in duplicate and analyzed by two-way ANOVA to determine the effect of BAY (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; n.s., non-significant).

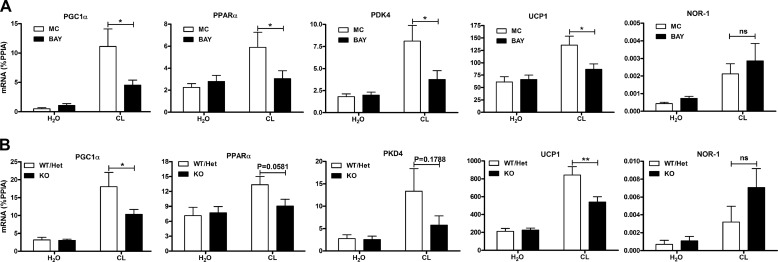

We next tested the role of HSL in mediating the induction of gene expression in BAT by challenging mice with the selective β3-AR agonist CL-316,243. CL induced the expression of PGC1α, PPARα, PDK4, UCP1, and NOR-1 in BAT (Fig. 2A), whereas BAY reduced the induction of PGC1α, PPARα, PDK4, and UCP1 but not NOR-1. As an additional test of the in vivo role of HSL, we challenged WT/Het and HSL-KO mice with CL. CL induced the expression of PGC1α, PPARα, PDK4, UCP1, and NOR-1 in WT/Het mice; this effect was reduced in HSL-KO mice for PGC1α and UCP1, with trends for reduction of PPARα (p = 0.058) and PDK4 (p = 0.18) (Fig. 2B). The induction of NOR-1 was similar between WT/Het and HSL-KO mice.

FIGURE 2.

HSL is required for β3-AR-mediated induction of thermogenic genes in BAT. A, mice (n = 11) were pretreated with BAY (30 mg/kg) or methylcellulose (MC) for 1 h followed by CL (10 nmol) or vehicle (H2O) for 3 h, and BAT was analyzed for mRNA expression by QPCR and normalized to percent PPIA. B, mice (n = 13) (WT, Het, or deficient for HSL (KO)) were treated with CL (10 nmol) for 6 h, and BAT was analyzed for mRNA as described in A. The effect of BAY (two-way ANOVA) or the difference between WT/Het and HSL-KO mice (two-way ANOVA) is indicated (**, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, non-significant).

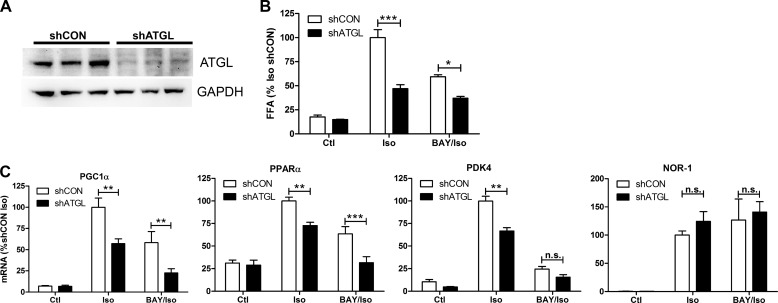

In addition to HSL, adipocytes express ATGL, which is believed to be the rate-limiting enzyme for lipolysis. The role of ATGL in the induction of genes by β-AR activation was tested by making stable cell lines expressing a control shRNA (shCON) or shRNA against ATGL (shATGL) in the brown adipocytes. Stable knockdown effectively reduced the protein levels of ATGL (Fig. 3A) and significantly diminished fatty acid levels after β-AR agonist treatment (Fig. 3B). Isoproterenol induced the expression of PGC1α, PPARα, and PDK4, and this induction was lower in shATGL cells (Fig. 3C). Isoproterenol also increased the expression of NOR-1, but the level of mRNA expression was equally increased in shATGL cells. Further reduction in lipolysis by inhibition of HSL (Fig. 3B) reduced the induction of PGC1α and PPARα (Fig. 3C) in shATGL cells. Overall, these results indicate that lipolysis via the activity of lipases ATGL and HSL is required for the maximal induction of thermogenic gene expression in response to β-AR activation in brown adipocytes.

FIGURE 3.

Knockdown of ATGL reduces the induction of oxidative genes by β-AR activation in brown adipocytes. A, Western blot was performed on shCON and shATGL brown adipocytes for ATGL and GAPDH. B, medium free fatty acids (FFA) were measured after 4 h and expressed as -fold isoproterenol (Iso). Ctl, control. C, shCON and shATGL brown adipocytes were treated with isoproterenol (10 μm) or BAY and isoproterenol (BAY/Iso), for 4 h, and mRNA levels were measured by QPCR, normalized to percent PPIA, and expressed as a percentage of shCON isoproterenol. Data are from three separate experiments performed in duplicate, and the difference between shCON and shATGL cells by two-way ANOVA is indicated (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; n.s., non-significant).

Increasing Fatty Acids Promotes Thermogenic Gene Transcription in Brown Adipocytes

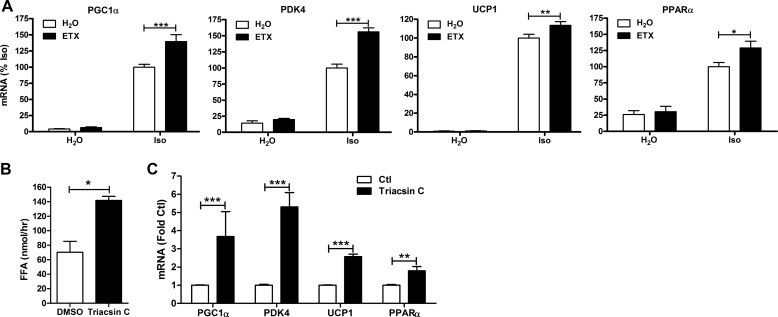

To further address whether lipolytic products play a role in positively regulating gene transcription, we tested the effects of increasing endogenous fatty acid levels. First, we modulated fatty acid levels, blocking their oxidation by inhibiting carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), the rate-limiting step for entry of fatty acids into the mitochondria. Treatment with etomoxir, an inhibitor of CPT1, did not have any effect on basal gene expression, nor did it affect extracellular lipolysis (not shown), but it potentiated the induction of PGC1α, PDK4, and PPARα by isoproterenol (Fig. 4A). Secondly, the activation of fatty acids was blocked by inhibiting the activity of long chain acyl-CoA synthetase, an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of fatty acyl-CoA. Inhibiting long chain acyl-CoA synthetase activity with triacsin C elevated fatty acid levels (Fig. 4B) and was sufficient to induce the expression of PGC1α, PDK4, UCP1, and PPARα in the absence of PKA activation (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that endogenous fatty acids are sufficient to promote the expression of thermogenic genes in brown adipocytes.

FIGURE 4.

Endogenous fatty acids increase the transcription of genes involved in thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. A, brown adipocytes were treated with etomoxir (ETX; 50 μm) or vehicle (H2O) followed by isoproterenol (Iso; 10 μm) for 4 h. mRNA levels were measured by QPCR, normalized to percent PPIA, and expressed as percent Iso. B, brown adipocytes were treated with triacsin C or vehicle (DMSO), and medium free fatty acids (FFA) were measured after 4 h and expressed as nmol/h. C, brown adipocytes were treated as described in B, and mRNA levels were quantified by QPCR and expressed as -fold of control (Ctl). Data are from 3–4 separate experiments performed in duplicate, and the effect of etomoxir or triacsin C is shown (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

PPARα and PPARδ Mediate the Induction of Gene Expression by β-AR Activation in Brown Adipocytes

We next addressed the mechanism by which lipolytic products increase thermogenic gene expression in brown adipocytes. The promoter regions of the PGC1α, PDK4, and UCP1 genes contain binding sites for the family of nuclear receptor PPARs. The PPARs are key regulators of lipid metabolism that are activated by lipids to promote gene transcription. We tested the role of PPARs and their binding partner, retinoid X receptor, in modulating β-AR-mediated gene expression by first using selective antagonists (not shown and Fig. 5, A and C). Only receptor antagonists against PPARα and -δ significantly reduced the induction of gene expression in brown adipocytes (Fig. 5A). Neither the PPARα nor PPARδ antagonist had any effect on lipolysis (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, did not affect the induction of genes by β-AR agonism (Fig. 5C). Because pharmacological probes can have issues with selectivity, we performed siRNA knockdown of PPARα and PPARδ. Targeted siRNAs effectively knocked down mRNA levels of PPARα and -δ (Fig. 5B) without affecting lipolysis (Fig. 5F). siRNA knockdown of PPARα significantly reduced the induction of PGC1α, PDK4, and UCP1 by isoproterenol, but not NOR-1, whereas knockdown of PPARδ effectively reduced the up-regulation of PDK4 and UCP1 (Fig. 5E). These results demonstrate that PPARα and -δ detect lipolytic products to promote the expression of oxidative genes.

FIGURE 5.

PPARα and PPARδ mediate the maximal induction of thermogenic genes by β-AR activation in brown adipocytes. A, brown adipocytes were treated with antagonists against PPARα (GW6741; 10 μm) or PPARδ (GSK0660; 2 μm) followed by isoproterenol (Iso; 10 μm) for 4 h. mRNA levels were measured by QPCR, normalized to percent PPIA, and expressed as a percent of isoproterenol. Data are from four separate experiments performed in duplicate, and the effect of GW6471 or GSK0660 by two-way ANOVA is shown (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05). B, free fatty acid (FFA) levels from A were measured in the medium and expressed as nmol/h. C, brown adipocytes were treated with PPARγ antagonist (GW9662, 30 μm) followed by isoproterenol for 4 h. The differences between groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA. D, mRNA levels of PPARα and -δ in brown adipocytes treated with control (siCON), PPARα (siPPARα), or PPARδ (siPPARδ) siRNA normalized to percent PPIA and expressed as -fold siCON. E, siCON-, siPPARα-, or siPPARδ-treated brown adipocytes were stimulated with isoproterenol for 4 h, and mRNA was quantified as described in A and expressed as a percent of siCON isoproterenol. Data are from three separate experiments performed in triplicate, and the effect of siPPARα or siPPARδ by two-way ANOVA is shown (***, p < 0.001; n.s., non-significant). F, free fatty acid levels in the medium from E were measured and expressed as nmol/h.

Lipid Droplets Generate Ligands That Transcriptionally Activate PPARα and -δ but Not PPARγ

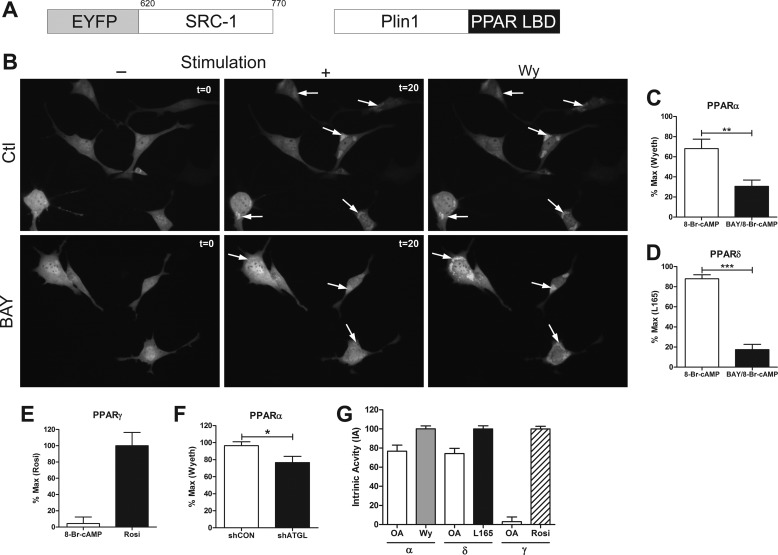

We investigated whether acute activation of lipolysis generates agonists for PPARα and PPARδ. Class II nuclear receptors are activated when agonists enter the nucleus, bind their receptors, and recruit co-activator molecules. Although the mechanisms of nuclear receptor activation are well known, the pathways that produce ligands and their sites of production are poorly understood. We tested whether ligands for PPARs are generated by lipid droplets using a fluorescent reporter assay that is based upon the binding of the transcriptional co-activator SRC1 to PPARs. In this assay, we fused the ligand-binding domain of PPARs to the lipid droplet protein Perilipin-1 (Plin1), and the LXXLL domain of SRC1 to EYFP (Fig. 6A). Thus, PPAR ligands that are generated by lipolysis are detected by the translocation of EYFP-SRC1 to the Plin1-PPAR ligand-binding domain fusion at the lipid droplet surface. As expected, EYFP-SRC1 was largely cytosolic in brown adipocytes under basal conditions (Fig. 6B). EYFP-SRC1 translocated to the droplet surface within minutes after the addition of 8-Br-cAMP, and fluorescence intensity continued to increase for 20 min (Fig. 6B, arrows, and supplemental Movie 1). Treatment with the HSL inhibitor greatly reduced the recruitment of EYFP-SRC1 to the lipid droplet surface (Fig. 6B, arrows, and supplemental Movie 2). To ensure that the fluorescent reporter could be activated in the presence of BAY, the PPARα agonist Wy-14,263 was added to fully stimulate the reporter (Fig. 6B, Wy). Normalizing the data to the maximal effect induced by Wy, we found that inhibition of HSL significantly reduced the activation of the PPARα reporter (Fig. 6C). Similarly, 8-Br-cAMP increased the activity of the PPARδ reporter; this effect was nearly abolished by HSL inhibition (Fig. 6D). In contrast, PPARγ was activated with rosiglitazone, but not by 8-Br-cAMP (Fig. 6E). All three activated PPAR reporters were correctly targeted to lipid droplets (data not shown). Knockdown of ATGL also reduced activation of the PPARα fluorescent reporter (Fig. 6F), whereas the addition of exogenous fatty acids was sufficient to activate PPARα and -δ but not PPARγ (Fig. 6G). 8-Br-cAMP activated PPARα and -δ nearly as much as did exogenous oleic acid (80%) (Fig. 6G).

FIGURE 6.

Ligands for PPARα and -δ, but not PPARγ, are created at the lipid droplet surface in response to lipolysis. A, schematic representation of constructs used for the fluorescent reporter assays (amino acids for SRC1 are shown). Plin1, Perilipin-1; LBD, ligand-binding domain. B, brown adipocytes transfected with a PPARα fluorescent reporter were pretreated with DMSO (Ctl) or BAY (5 μm) for 10 min. Representative images shown prior to stimulation with 1 mm 8-Br-cAMP (−; t = 0) or after 20 min of stimulation (+; t = 20) and after the addition of PPARα ligand, Wy (100 μm). C, the PPARα reporter was quantified by normalizing the region of interest after treatment with 8-Br-cAMP or BAY/8-Br-cAMP to the maximal effect of Wy-14,263 (Wyeth) from 2–3 coverslips/experiment (n = 3). D, the PPARδ reporter was normalized to the maximal effect of L165 (10 μm). The effect of BAY was determine by unpaired t test (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01). E, the PPARγ reporter was quantified by normalizing the region of interest after 8-Br-cAMP to the maximal effect of rosiglitazone (Rosi, 10 μm). F, the PPARα reporter was quantified in shCON and shATGL brown adipocytes after treatment with 8-Br-cAMP as above, and the difference was determine by unpaired t test (*, p < 0.05). G, brown adipocytes transfected with reporters for PPARα, -δ, and -γ were treated with 400 μm oleic acid (OA), and the data were normalized to the intrinsic activity (IA) of the respective ligands, Wy, L165, and rosiglitazone.

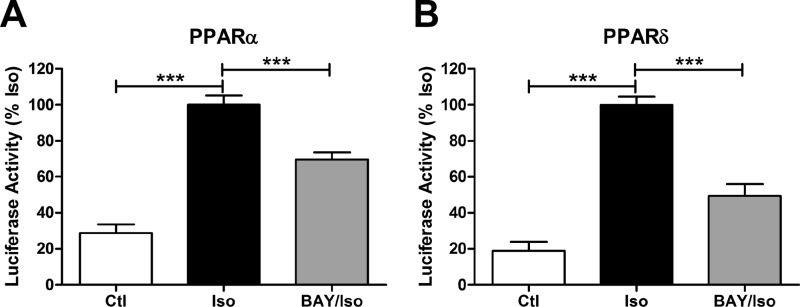

We also tested the role of lipolytic products in activating PPARα and -δ transcription. As expected, β-AR stimulation induced transcription of Gal4-PPARα and Gal4-PPARδ reporters, and this effect was reduced with HSL inhibition (Fig. 7). Overall, these results demonstrate that ligands for PPARα and -δ are generated at the lipid droplet surface and increase the transcriptional activity of PPARα and -δ.

FIGURE 7.

Lipolysis activates PPARα and PPARδ transcription. Brown adipocytes transfected with β-galactosidase, luciferase reporter, and hPPARα-Gal4 (A) or hPPARδ-Gal4 (B) fusions were treated with vehicle (Ctl) or BAY (5 μm) and stimulated with isoproterenol (Iso; 10 μm) for 8 h. Luciferase reporter activity was normalized to β-gal activity and expressed as a percent of isoproterenol, and statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA to determine the effect of BAY or isoproterenol (***, p < 0.001).

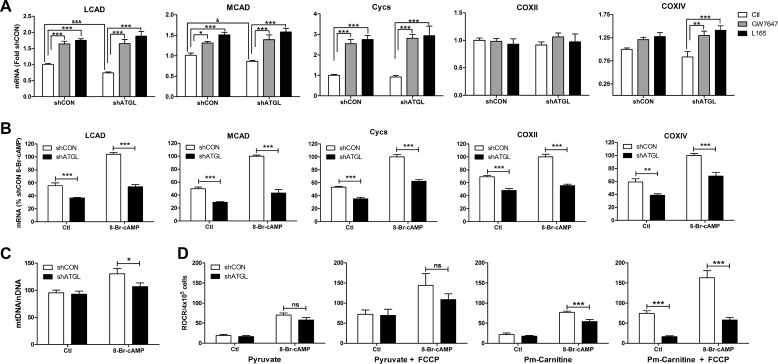

Knockdown of ATGL Reduces PKA Up-regulation of Mitochondrial Gene Expression and Fatty Acid Oxidation

β-AR activation increases mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in brown adipocytes (25), but it is not known whether lipolysis participates in this regulation. First we tested the effects of direct activation of PPARα and -δ on mitochondrial gene expression. Basal gene expression of long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) and medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) was lower in shATGL brown adipocytes. Direct agonists of PPARα and -δ elevated the expression of LCAD, MCAD, cytochrome c, and cytochrome c oxidase IV (COXIV) similarly in control and ATGL shRNA expressing brown adipocytes (Fig. 8A). These results demonstrate that activation of PPARα and -δ is sufficient to elevate the expression of mitochondrial genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation. We next tested whether stimulation with cAMP could increase the expression of mitochondrial genes equally in shCON and shATGL brown adipocytes. Stimulation with the cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP for 24 h induced the expression of LCAD, MCAD, cytochrome c, COXII, and COXIV in shCON brown adipocytes (Fig. 8B). Although basal gene expression was variable, the levels of LCAD, MCAD, cytochrome c, COXII, and COXIV were lower in shATGL cells in the unstimulated state. Importantly, the ability of cAMP to up-regulate mitochondrial gene expression was compromised in ATGL knockdown cells (Fig. 8B). Together, these results demonstrate that the defect in the ability of cAMP to increase mitochondrial gene expression in shATGL cells occurs at the level of ligand production.

FIGURE 8.

ATGL is required for the maximal increase in mitochondrial gene expression and fatty acid oxidation in response to cAMP stimulation in brown adipocytes. A, brown adipocytes expressing a control (shCON) or ATGL (shATGL) shRNA were treated with agonists against PPARα (GW7647; 1 μm) and δ (L165; 5 μm) for 24 h. mRNA levels were measured by QPCR, normalized to percent PPIA, and expressed as -fold shCON. Measurements are from an average of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA to determine the effect of GW7647 or L165 in comparison with control (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01) or by post hoc t test to determine the effect of ATGL knockdown (***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05). Cycs, cytochrome c. B, the indicated cells were treated with H2O (Ctl) or 8-Br-cAMP for 24 h, and mRNA levels were quantified by QPCR, normalized to percent PPIA, and expressed as a percent shCON 8-Br-cAMP. Measurements are from an average of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA to determine the effect of ATGL knockdown (shATGL) (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01). C, mtDNA normalized to nDNA in shCON and shATGL brown adipocytes in control state (Ctl) or treated with 8-Br-cAMP for 48 h (*, p < 0.05). D, relative mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (ROCR) in permeabilized shCON and shATGL brown adipocytes using pyruvate or palmitoylcarnitine (Pm-Carnitine) as substrate. ADP-driven (Pyruvate and Pm-Carnitine) and fully stimulated (Pyruvate + FCCP and Pm-Carnitine + FCCP) respiration is shown. Measurements are from an average of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA to determine the effect of ATGL knockdown (shATGL) (***, p < 0.001; ns, non-significant).

Lastly, we examined the effect of ATGL knockdown on mitochondrial content and function. Treatment with the cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP for 48 h increased mitochondrial DNA content in brown adipocytes, an effect that was reduced in shATGL brown adipocytes (Fig. 8C). There was no significant effect of ATGL knockdown on mitochondrial DNA content in the basal state. 8-Br-cAMP increased coupled (ADP) and fully uncoupled (FCCP) respiration when pyruvate was used as the substrate for oxidation; however, knockdown of ATGL did not significantly affect the oxidation of pyruvate (Fig. 8D). 8-Br-cAMP also increased the oxidation of palmitoylcarnitine. However, in contrast to pyruvate, oxidation of palmitoylcarnitine was reduced in cells with knockdown of ATGL, particularly when mitochondria were uncoupled and fatty acid oxidation was limiting for mitochondrial electron transport (Fig. 8D).

DISCUSSION

Thermogenesis in BAT requires activation of the β-AR signaling cascade. Within this signaling network are two pathways that have long been viewed as independent. The first is lipolysis, which mobilizes fatty acids that both activate UCP1 and provide fuel for thermogenesis. The second pathway comprises transcriptional events that expand the capacity for oxidative metabolism. The present work, exploring the interactions between these pathways, demonstrates that acute fatty acid mobilization potentiates cAMP-dependent gene transcription in brown adipocytes.

We manipulated lipolysis by pharmacological inhibition of HSL and knockdown of ATGL and found that lipolysis was required for the optimal induction of PGC1α, PPARα, PDK4, and UCP1 by PKA in brown adipocytes. Inhibition of HSL further reduced the induction of genes by β-AR agonism in ATGL knockdown cells, indicating that lipolysis is the predominant pathway by which β-ARs regulate the expression of oxidative genes. Furthermore, the additive effect of HSL inhibition on ATGL knockdown indicates that the lipases control gene transcription over a range of lipolysis. Importantly, the lipolysis-dependent regulation of gene transcription was independent of the lipase, suggesting that both ATGL and HSL produce similar ligands for PPARs. The fact that HSL inhibition in vivo did not completely block the induction of certain genes by β-AR is likely explained by the direct effects of PKA phosphorylation on transcription factors like CREB (6) or the residual effects of lipolysis mediated by ATGL.

The promoter elements of PGC1α (26), PDK4 (27), and UCP1 (28) contain PPAR response elements and likely define the means by which lipolysis regulates their expression. Lipolytic products are detected by PPARα and PPARδ, which are both critical regulators of the thermogenic program in BAT (16, 29). In agreement, both PPARα (16, 26) and PPARδ (29–31) bind the UCP1 and PDK4 (27, 32) promoters. Interestingly, the PGC1α PPAR response element is responsive to PPARα but not PPARδ (33); this is in agreement with our antagonist and siRNA studies in which only PPARα modulation affected PGC1α expression.

Our current results demonstrate PPARα and -δ ligands are detected at the lipid droplet surface within minutes of PKA activation and can transcriptionally activate PPARα and -δ over a period of hours. The fact that PPARα/δ ligand generation was rapid, profoundly suppressed by HSL inhibition, and mimicked by exogenous oleic acid indicates that mobilized fatty acids are likely endogenous ligands. Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that additional ligands are generated from the metabolism of fatty acids, especially at later time points. How fatty acids traffic from the lipid droplet to the nucleus to activate PPARs is not currently known, but it might involve fatty acid-binding proteins (34). Although the role of lipolysis in activating PPARα in brown adipocytes has been suggested (26, 33), our results demonstrate unequivocally that PPARα is activated as a consequence of the activities of ATGL and HSL. Of note, inhibition of long chain acyl-CoA synthetases without adrenergic stimulation was effective in activating gene transcription, but CPT1 inhibition alone was not, suggesting that fatty acid flux might be critical in ligand production. The identity of the endogenous PPARα and -δ ligand produced during lipolysis is likely a long chain non-esterified fatty acid, as increasing endogenous fatty acid levels by inhibition of long chain acyl-CoA synthetases and CPT1 was sufficient to elevate gene expression. In addition, oleic acid was sufficient to activate PPARα and -δ within seconds of its addition in live cell fluorescent reporter assays. Interestingly, fatty acids are potent activators of PPARα and -δ but have weak to no activity on PPARγ (35), supporting our results in the differential response of PPARs to lipolytic products. In addition, the PPARγ antagonist did not affect the induction of genes by β-AR, which further supports our findings that PPARγ is not involved in the lipolytic response in brown adipocytes. PPARγ might be important in the initial commitment of brown adipocytes (36).

We used knockdown of ATGL, thought to be the rate-limiting lipase, as a model to study the role of lipolysis on mitochondrial function because it provides a more sustained inhibition of lipolysis over pharmacological inhibition of HSL. Knockdown of ATGL significantly reduced the induction of LCAD and MCAD, which are rate-limiting enzymes for mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, and impaired oxidation of palmitoylcarnitine but not pyruvate. Cells lacking ATGL were fully responsive to exogenous PPARα and -δ ligands but were less responsive to 8-Br-cAMP, indicating that the defect in gene regulation involves ATGL-dependent production of PPAR ligands. There was no effect of ATGL knockdown on pyruvate metabolism, suggesting that the expression of mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial content is not rate-limiting for glucose oxidation.

Excessive fatty acids are toxic in a variety of cells, and the relationship between ATGL and the rate-limiting enzymes for β-oxidation suggests a feedback loop that permits fatty acid oxidation to be closely matched to mobilization. Thus, fatty acid mobilization activates PPARα and -δ and augments the capacity to oxidize fatty acids. ATGL and HSL are known PPARα targets in the liver (37), which might further expand this positive feedback loop between PPARs and lipases in brown adipocytes. These feedback responses increase the expression of PPARα and PGC1α, which are both critical for thermogenesis in BAT (16, 38). In doing so, the thermogenic capacity is expanded, and the toxic effects of elevated intracellular fatty acids are avoided (see below).

A similar principle holds true for WAT, although the mechanisms differ. The main fate of fatty acids in WAT is extracellular efflux. Excessive fatty acid production in white adipocytes produces local inflammation (14) and inhibits cAMP production (9), thereby matching lipase activation with extracellular fatty acid clearance. This acute inflammatory response recruits macrophages that have anti-lipolytic properties, providing an additional mechanism to reduce lipolysis (13). Lipolytic products in white fat balance production with efflux, whereas fatty acids in brown fat function to balance production with oxidation. The transcriptional response to products of lipolysis in white fat and brown fat reflects the functional differences of lipolysis in these tissues: in white fat mobilized fatty acids are released, whereas in brown fat, fatty acids activate UCP1 and provide fuel for thermogenesis (39). An additional means by which white fat counters the detrimental effects of fatty acids over a longer time frame is to increase a fatty acid oxidation program via the up-regulation of PPARα (15). This browning of white fat likely also involves lipase-generated PPAR ligands (11), whereby lipolysis may be an initiating factor in recruiting adult adipocyte progenitor cells into a brown adipocyte lineage (40).

Our data demonstrate that ligands for PPARs can be generated by lipases at the lipid droplet surface; however, the source of endogenous ligand production, as well as the nature of the ligand itself, likely differs by tissue and metabolic stimulus. Fatty acids derived from fatty-acid synthase (41) or intracellular (42) and extracellular lipolysis (43) can activate PPARα in the liver, whereas lipoprotein lipase is a source of PPARα ligands in the heart (44). Extracellular fatty acids are also a source of ligands for PPARδ in β-cells (45) and the liver (46). It is likely that ATGL-mediated lipolysis in heart (12) and liver (47) activates PPARα to regulate mitochondrial gene expression and fatty acid oxidation. In addition, hepatic overexpression of ATGL or HSL increases fatty acid oxidation and ameliorates steatosis (48).

The function of brown adipose tissue in rodents is to maintain body temperature during exposure to cold by generating heat. Recent evidence demonstrates that adult humans have functional brown adipose tissue (49), although the physiological importance of BAT in adult humans remains a matter of debate (50). Pharmacological activation of BAT in rodents has anti-obesity effects and improves insulin sensitivity, and it has been suggested that BAT might be a therapeutic target for obesity and diabetes in humans. Consistent with the activation of lipolysis as a therapeutic target, overexpression of ATGL reprograms WAT to a more oxidative phenotype (51), and mouse models with enhanced lipolysis have increased fatty acid oxidation and a lean phenotype (52–54). Based on our current results, dual synthetic agonists of PPARα and -δ or direct activators of lipolysis might prove useful in expanding oxidation in BAT or in promoting the browning of WAT (14).

Acknowledgments

We thank Li Zhou for technical support and Drs. Robert MacKenzie, Jian Wang, and Yun-Hee Lee for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK092741, DK076229, and DK062292. This work also was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

This article contains supplemental Movies 1 and 2.

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- β-AR

- β-adrenergic receptor

- UCP1

- uncoupling protein 1

- PGC1α

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- ATGL

- adipose tissue triglyceride lipase

- HSL

- hormone-sensitive lipase

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

- BAY

- BAY 59–9435

- CL

- CL-316,243

- Het

- heterozygous

- QPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SRC1

- steroid receptor co-activator 1

- EYFP

- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- Wy

- Wy-14,643

- L165

- L-165,041

- aa

- amino acid

- CPT1

- carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1

- PPIA

- peptidylprolyl isomerase A

- CREB

- cAMP response element-binding protein

- NOR-1

- neuron-derived orphan receptor-1

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- LCAD

- long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- MCAD

- medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- FCCP

- carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- shCON

- control shRNA

- shATGL

- shRNA against ATGL

- 8-Br-cAMP

- 8-bromo-cyclic AMP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Puigserver P., Wu Z., Park C. W., Graves R., Wright M., Spiegelman B. M. (1998) A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92, 829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spiegelman B. M. (2007) Transcriptional control of mitochondrial energy metabolism through the PGC1 coactivators. Novartis Found. Symp. 287, 60–63; discussion 63–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chang J. S., Fernand V., Zhang Y., Shin J., Jun H. J., Joshi Y., Gettys T. W. (2012) NT-PGC-1α protein is sufficient to link β3-adrenergic receptor activation to transcriptional and physiological components of adaptive thermogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9100–9111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reusch J. E., Colton L. A., Klemm D. J. (2000) CREB activation induces adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1008–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rim J. S., Kozak L. P. (2002) Regulatory motifs for CREB-binding protein and Nfe2l2 transcription factors in the upstream enhancer of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34589–34600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karamitri A., Shore A. M., Docherty K., Speakman J. R., Lomax M. A. (2009) Combinatorial transcription factor regulation of the cyclic AMP-response element on the Pgc-1α promoter in white 3T3-L1 and brown HIB-1B preadipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20738–20752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Granneman J. G., Moore H. P., Granneman R. L., Greenberg A. S., Obin M. S., Zhu Z. (2007) Analysis of lipolytic protein trafficking and interactions in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5726–5735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kraemer F. B., Shen W. J. (2002) Hormone-sensitive lipase: control of intracellular tri-(di-)acylglycerol and cholesteryl ester hydrolysis. J. Lipid Res. 43, 1585–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mottillo E. P., Granneman J. G. (2011) Intracellular fatty acids suppress β-adrenergic induction of PKA-targeted gene expression in white adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 301, E122–E131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mottillo E. P., Shen X. J., Granneman J. G. (2010) β3-Adrenergic receptor induction of adipocyte inflammation requires lipolytic activation of stress kinases p38 and JNK. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801, 1048–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mottillo E. P., Shen X. J., Granneman J. G. (2007) Role of hormone-sensitive lipase in β-adrenergic remodeling of white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 293, E1188–E1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haemmerle G., Moustafa T., Woelkart G., Büttner S., Schmidt A., van de Weijer T., Hesselink M., Jaeger D., Kienesberger P. C., Zierler K., Schreiber R., Eichmann T., Kolb D., Kotzbeck P., Schweiger M., Kumari M., Eder S., Schoiswohl G., Wongsiriroj N., Pollak N. M., Radner F. P., Preiss-Landl K., Kolbe T., Rülicke T., Pieske B., Trauner M., Lass A., Zimmermann R., Hoefler G., Cinti S., Kershaw E. E., Schrauwen P., Madeo F., Mayer B., Zechner R. (2011) ATGL-mediated fat catabolism regulates cardiac mitochondrial function via PPAR-α and PGC-1. Nat. Med. 17, 1076–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kosteli A., Sugaru E., Haemmerle G., Martin J. F., Lei J., Zechner R., Ferrante A. W. (2010) Weight loss and lipolysis promote a dynamic immune response in murine adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3466–3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Granneman J. G., Li P., Zhu Z., Lu Y. (2005) Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue I: effects of β3-adrenergic receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 289, E608–E616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li P., Zhu Z., Lu Y., Granneman J. G. (2005) Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue II: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 289, E617–E626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmadian M., Abbott M. J., Tang T., Hudak C. S., Kim Y., Bruss M., Hellerstein M. K., Lee H. Y., Samuel V. T., Shulman G. I., Wang Y., Duncan R. E., Kang C., Sul H. S. (2011) Desnutrin/ATGL is regulated by AMPK and is required for a brown adipose phenotype. Cell Metab. 13, 739–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee C. H., Olson P., Evans R. M. (2003) Minireview: lipid metabolism, metabolic diseases, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Endocrinology 144, 2201–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahmed W., Ziouzenkova O., Brown J., Devchand P., Francis S., Kadakia M., Kanda T., Orasanu G., Sharlach M., Zandbergen F., Plutzky J. (2007) PPARs and their metabolic modulation: new mechanisms for transcriptional regulation? J. Intern. Med. 262, 184–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uldry M., Yang W., St-Pierre J., Lin J., Seale P., Spiegelman B. M. (2006) Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 3, 333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Granneman J. G., Moore H. P., Krishnamoorthy R., Rathod M. (2009) Perilipin controls lipolysis by regulating the interactions of AB-hydrolase containing 5 (Abhd5) and adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34538–34544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jonckheere A. I., Huigsloot M., Janssen A. J., Kappen A. J., Smeitink J. A., Rodenburg R. J. (2010) High-throughput assay to measure oxygen consumption in digitonin-permeabilized cells of patients with mitochondrial disorders. Clin. Chem. 56, 424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuznetsov A. V., Veksler V., Gellerich F. N., Saks V., Margreiter R., Kunz W. S. (2008) Analysis of mitochondrial function in situ in permeabilized muscle fibers, tissues, and cells. Nat. Protoc. 3, 965–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Will Y., Hynes J., Ogurtsov V. I., Papkovsky D. B. (2006) Analysis of mitochondrial function using phosphorescent oxygen-sensitive probes. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2563–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo W., Jiang L., Bhasin S., Khan S. M., Swerdlow R. H. (2009) DNA extraction procedures meaningfully influence qPCR-based mtDNA copy number determination. Mitochondrion 9, 261–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Néchad M., Nedergaard J., Cannon B. (1987) Noradrenergic stimulation of mitochondriogenesis in brown adipocytes differentiating in culture. Am. J. Physiol. 253, C889–C894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barbera M. J., Schluter A., Pedraza N., Iglesias R., Villarroya F., Giralt M. (2001) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activates transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein-1 gene. A link between regulation of the thermogenic and lipid oxidation pathways in the brown fat cell. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1486–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Degenhardt T., Saramäki A., Malinen M., Rieck M., Väisänen S., Huotari A., Herzig K. H., Müller R., Carlberg C. (2007) Three members of the human pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene family are direct targets of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kozak U. C., Kopecky J., Teisinger J., Enerbäck S., Boyer B., Kozak L. P. (1994) An upstream enhancer regulating brown fat-specific expression of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Y. X., Lee C. H., Tiep S., Yu R. T., Ham J., Kang H., Evans R. M. (2003) Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor δ activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell 113, 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan D., Fujimoto M., Lopes A., Wang Y. X. (2009) Twist-1 is a PPARδ-inducible, negative feedback regulator of PGC-1α in brown fat metabolism. Cell 137, 73–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gan Z., Burkart-Hartman E. M., Han D. H., Finck B., Leone T. C., Smith E. Y., Ayala J. E., Holloszy J., Kelly D. P. (2011) The nuclear receptor PPARβ/δ programs muscle glucose metabolism in cooperation with AMPK and MEF2. Genes Dev. 25, 2619–2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Montgomery R. L., Potthoff M. J., Haberland M., Qi X., Matsuzaki S., Humphries K. M., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2008) Maintenance of cardiac energy metabolism by histone deacetylase 3 in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3588–3597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hondares E., Rosell M., Díaz-Delfín J., Olmos Y., Monsalve M., Iglesias R., Villarroya F., Giralt M. (2011) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) induces PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) gene expression and contributes to thermogenic activation of brown fat: involvement of PRDM16. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 43112–43122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Furuhashi M., Hotamisligil G. S. (2008) Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 489–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Forman B. M., Chen J., Evans R. M. (1997) Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and δ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4312–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kajimura S., Seale P., Spiegelman B. M. (2010) Transcriptional control of brown fat development. Cell Metab. 11, 257–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rakhshandehroo M., Sanderson L. M., Matilainen M., Stienstra R., Carlberg C., de Groot P. J., Müller M., Kersten S. (2007) Comprehensive analysis of PPARα-dependent regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism by expression profiling. PPAR Res. 2007, 26839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leone T. C., Lehman J. J., Finck B. N., Schaeffer P. J., Wende A. R., Boudina S., Courtois M., Wozniak D. F., Sambandam N., Bernal-Mizrachi C., Chen Z., Holloszy J. O., Medeiros D. M., Schmidt R. E., Saffitz J. E., Abel E. D., Semenkovich C. F., Kelly D. P. (2005) PGC-1α deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control and hepatic steatosis. PLoS Biol. 3, e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nicholls D. G., Rial E. (1999) A history of the first uncoupling protein, UCP1. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 31, 399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee Y. H., Petkova A. P., Mottillo E. P., Granneman J. G. (2012) In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by β3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 15, 480–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chakravarthy M. V., Lodhi I. J., Yin L., Malapaka R. R., Xu H. E., Turk J., Semenkovich C. F. (2009) Identification of a physiologically relevant endogenous ligand for PPARα in liver. Cell 138, 476–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sapiro J. M., Mashek M. T., Greenberg A. S., Mashek D. G. (2009) Hepatic triacylglycerol hydrolysis regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activity. J. Lipid Res. 50, 1621–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruby M. A., Goldenson B., Orasanu G., Johnston T. P., Plutzky J., Krauss R. M. (2010) VLDL hydrolysis by LPL activates PPAR-α through generation of unbound fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2275–2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duncan J. G., Bharadwaj K. G., Fong J. L., Mitra R., Sambandam N., Courtois M. R., Lavine K. J., Goldberg I. J., Kelly D. P. (2010) Rescue of cardiomyopathy in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α transgenic mice by deletion of lipoprotein lipase identifies sources of cardiac lipids and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α activators. Circulation 121, 426–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ravnskjaer K., Frigerio F., Boergesen M., Nielsen T., Maechler P., Mandrup S. (2010) PPARδ is a fatty acid sensor that enhances mitochondrial oxidation in insulin-secreting cells and protects against fatty acid-induced dysfunction. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1370–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sanderson L. M., Degenhardt T., Koppen A., Kalkhoven E., Desvergne B., Müller M., Kersten S. (2009) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) but not PPARα serves as a plasma free fatty acid sensor in liver. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 6257–6267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ong K. T., Mashek M. T., Bu S. Y., Greenberg A. S., Mashek D. G. (2011) Adipose triglyceride lipase is a major hepatic lipase that regulates triacylglycerol turnover and fatty acid signaling and partitioning. Hepatology 53, 116–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reid B. N., Ables G. P., Otlivanchik O. A., Schoiswohl G., Zechner R., Blaner W. S., Goldberg I. J., Schwabe R. F., Chua S. C., Jr., Huang L. S. (2008) Hepatic overexpression of hormone-sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase promotes fatty acid oxidation, stimulates direct release of free fatty acids, and ameliorates steatosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13087–13099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ravussin E., Galgani J. E. (2011) The implication of brown adipose tissue for humans. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 31, 33–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Muzik O., Mangner T. J., Granneman J. G. (2012) Assessment of oxidative metabolism in brown fat using PET imaging. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 3, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ahmadian M., Duncan R. E., Varady K. A., Frasson D., Hellerstein M. K., Birkenfeld A. L., Samuel V. T., Shulman G. I., Wang Y., Kang C., Sul H. S. (2009) Adipose overexpression of desnutrin promotes fatty acid use and attenuates diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 58, 855–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tansey J. T., Sztalryd C., Gruia-Gray J., Roush D. L., Zee J. V., Gavrilova O., Reitman M. L., Deng C. X., Li C., Kimmel A. R., Londos C. (2001) Perilipin ablation results in a lean mouse with aberrant adipocyte lipolysis, enhanced leptin production, and resistance to diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6494–6499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Martinez-Botas J., Anderson J. B., Tessier D., Lapillonne A., Chang B. H., Quast M. J., Gorenstein D., Chen K. H., Chan L. (2000) Absence of perilipin results in leanness and reverses obesity in Lepr(db/db) mice. Nat. Genet. 26, 474–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nishino N., Tamori Y., Tateya S., Kawaguchi T., Shibakusa T., Mizunoya W., Inoue K., Kitazawa R., Kitazawa S., Matsuki Y., Hiramatsu R., Masubuchi S., Omachi A., Kimura K., Saito M., Amo T., Ohta S., Yamaguchi T., Osumi T., Cheng J., Fujimoto T., Nakao H., Nakao K., Aiba A., Okamura H., Fushiki T., Kasuga M. (2008) FSP27 contributes to efficient energy storage in murine white adipocytes by promoting the formation of unilocular lipid droplets. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2808–2821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]