Abstract

Over the past several decades of cancer research, the inherent complexity of tumors has become increasingly appreciated. In addition to acquired cell-intrinsic properties, tumor growth is supported by an abundance of parenchymal, inflammatory and stromal cell types, which infiltrate and surround the tumor. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that numerous components of this supportive milieu, referred to collectively as the tumor microenvironment, are indeed critical during the process of multistep tumorigenesis. These findings highlight the important interplay between cancer cells and tumor-associated cell types, and suggest that cancer therapy should target both neoplastic cells and supportive stromal cells to effectively attenuate tumor growth. The nuclear receptor superfamily encompasses a druggable class of molecules expressed in numerous stromal and parenchymal cell types, whose established physiologic roles suggest therapeutic potential in the context of the reactive tumor microenvironment. In this minireview, we discuss recent evidence that tumor-associated inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis can be modulated at the transcriptional level by nuclear receptors and their ligands. As these processes have been widely implicated in cancer initiation, progression, and resistance to current therapy, nuclear receptors ligands targeting the tumor microenvironment may be potent antitumor agents in combination with chemotherapy.

Introduction

Solid tumors are no longer viewed simply as clonal expansions of cancer cells. Instead, the current view of the tumorigenic process posits that a tumor is a complex cellular expansion consisting of heterogeneous and ever-evolving cancer cells, and their co-evolving microenvironment1, 2. While alterations in the tumor cell genome have long been thought to drive tumor initiation and progression, the strong influence of non-malignant cells of the microenvironment on tumor growth has been more recently appreciated, and is only now beginning to be understood3. Indeed, solid tumors have come to be defined in part as complex networks of tumor cells in paracrine communication with cells of the microenvironment, including resident fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, and leukocytes, which serve critical functions in helping the cancer cells meet myriad requirements for their survival4, 5. For example, release of secreted factors such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)6, 7, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)8 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)9 by stromal fibroblasts has been shown to modulate the oncogenic and metastatic potential of adjacent epithelial tissues. Activated cancer-associated fibroblasts also deposit extracellular matrix (ECM) components that contribute to tumor cell survival and chemoresistance10-12. Additionally, activation of de novo angiogenesis supplies tumor cells with needed nutrients and oxygen, and is mediated by local stimulation of vascular endothelial cells with pro- and anti-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), respectively13, 14, as well as recruitment of vasculature-supporting pericytes15. Together, such tumor-derived factors activate the “angiogenic switch” characteristic of most neoplastic growths—activation of this process, normally dormant in adults, supports tumor growth as well as invasion and metastasis. Infiltrating leukocytes of the innate and adaptive immune systems also populate the tumor microenvironment, and it has become increasingly apparent that each stage of cancer development is susceptible to regulation by immune cells16, 17. Infiltrating immune cells engage in a complex crosstalk with tumor cells and other cell types of the tumor microenvironment via both protumorigenic and antitumorigenic mechanisms. Indeed, the same immune or inflammatory cell subtype may exhibit both protumorigenic and antitumorigenic functions. Depending on differentiation status and the presence of TGF-β, neutrophils, for example, demonstrate tumor-directed cytotoxicity as well as regulation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in certain contexts, and in others produce cytokines, proteases, and reactive oxygen species that promote tumor growth18. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are frequently found in the tumor microenvironment, and recent evidence suggests that the M2 macrophage subtype, commonly characteristic of TAMs, can produce cytokines which promote tumor angiogenesis and tissue remodeling as well as cytokines such as IL-10 with tumor suppressive potential19, 20. As tumor cells exhibit a remarkable dependence on their microenvironment for growth, the cell types and pathways therein may represent valuable targets for therapy.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are a superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate development, cellular differentiation, reproduction, and metabolism of lipids, drugs, and energy21. As intracellular sensors of lipophilic hormones, vitamins, dietary lipids, or other signals, NRs act as transcriptional switches to orchestrate responses to environmental cues at the level of gene expression22. Genomic sequence availability has led to the identification of 48 NRs encoded by the human genome and 49 NRs encoded by the mouse genome23-25. In addition to normal metabolic and homeostatic processes, NRs are important regulators of various disease states including diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, and cancer26, 27. The appreciated roles of various NRs in controlling proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis are suggestive of direct antitumor effects for NRs and their ligands on cancer cells, as has been demonstrated in numerous contexts. However, less attention has been paid to the putative therapeutic value of NRs and their ligands in the tumor microenvironment, where regulation by NRs of such processes as fibrosis, angiogenesis, and inflammation may complement cancer cell-targeted chemotherapy to blunt tumor growth.

While our understanding of the dynamic and extensive interactions between tumor cells and their surroundings remains incomplete, it seems clear that targeting both neoplastic cells and the stromal elements needed for their survival represents a promising avenue for cancer therapy. Indeed, anti-angiogenic strategies for cancer treatment are currently in place28 and under steady development29 for use in human patients, while endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis have yielded promising results in mouse models of cancer30. Compounds targeting inflammation and/or inflammatory immune cell types have also demonstrated encouraging antitumor effects. Several nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are appreciated anticancer agents31, particularly the highly selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors (refs), attributable in part to their anti-angiogenic properties. Accordingly, daily aspirin use has been shown to reduce the risk of developing several common cancer types32. In addition, recent work has demonstrated the utility of CD40 agonists in mice and humans to relieve immune suppression and promote tumoricidal T cell activity33-35, or to activate macrophages in a manner that promotes tumor cell killing and depletion of tumor stroma, leading to tumor regression even independent of chemotherapy36. Similarly, ablation of cancer-associated fibroblasts in several mouse models of cancer, via fibroblast activation protein-targeted vaccination37 or genetic engineering38, has been shown to reduce matrix deposition, improve chemotherapeutic drug uptake, and relieve local immune suppression, leading to a reduction in tumor burden. Together, these studies underscore the therapeutic potential of cancer treatment strategies targeting stromal cell types. Nuclear receptors, expressed in numerous stromal cell types and implicated in multiple cancer-related processes, represent a frequently druggable class of molecules with the intriguing potential to modulate the tumor microenvironment.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts and related stromal elements

Cancer-associated fibroblasts or stromal elements produce hormones, growth factors, cytokines, and other factors which may act in a paracrine manner to influence tumor initiation and progression. NRs in various contexts may act to inhibit these tumor-promoting functions of stromal cells. In the pancreas, carcinogenesis is associated with the transdifferentiation of stromal cells called pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) to a myofibroblast-like phenotype39. PSCs are the main cell type causing the desmoplastic reaction, a dramatic increase in connective tissue or stroma which infiltrates and surrounds the tumor. Desmoplastic stroma is a defining feature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common form of pancreatic cancer40, and contributes to tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and resistance to therapy41, 42. While quiescent PSCs act as retinol-storing cells with a limited secretome, activated PSCs in the desmoplastic stroma produce a vast array of secreted proteins implicated in fibrosis, proliferation, cell survival, and wound healing43. This suggests that restoration of the quiescent PSC phenotype may disrupt PSC-tumor cell communication and impair tumor growth. As retinol stores characterize quiescent PSCs and are lost upon activation, the ability of various forms of retinoic acid (RA) to promote PSC quiescence was investigated. Indeed, treatment of PSCs with RA results in activation of retinoic acid receptor β (RARβ) and induction of the quiescent state (Figure 1). This led to reduced Wnt-β-Catenin signaling in adjacent cancer cells, reduced motility, decreased ECM deposition, and slowing of tumor progression44. Similar effects on stellate cell activation state have been observed by treatment of closely related hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) with 1,25-(OH)2D3 or calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D45. Subsequent vitamin D receptor (VDR) activation led to decreased HSC proliferation and profibrotic marker expression, and to decreased liver fibrosis in vivo. This highlights the potential utility of VDR ligands in the reversal of pre-malignant conditions such as hepatic fibrosis (Figure 2), and suggests that these ligands may be of value in targeting PSCs in the pancreatic cancer microenvironment.

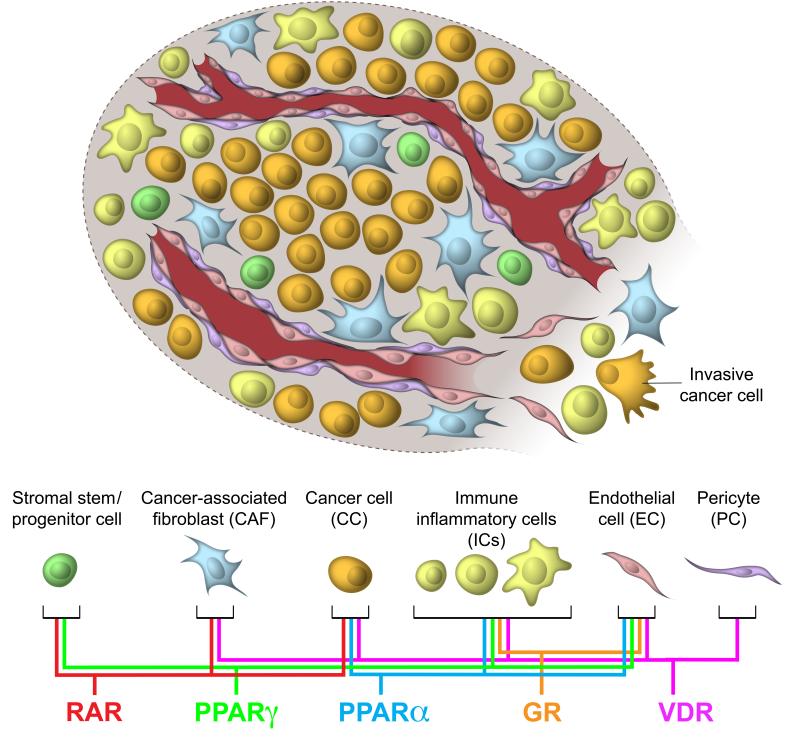

Figure 1.

Sites of action of ligand-activated nuclear receptors in the tumor microenvironment.

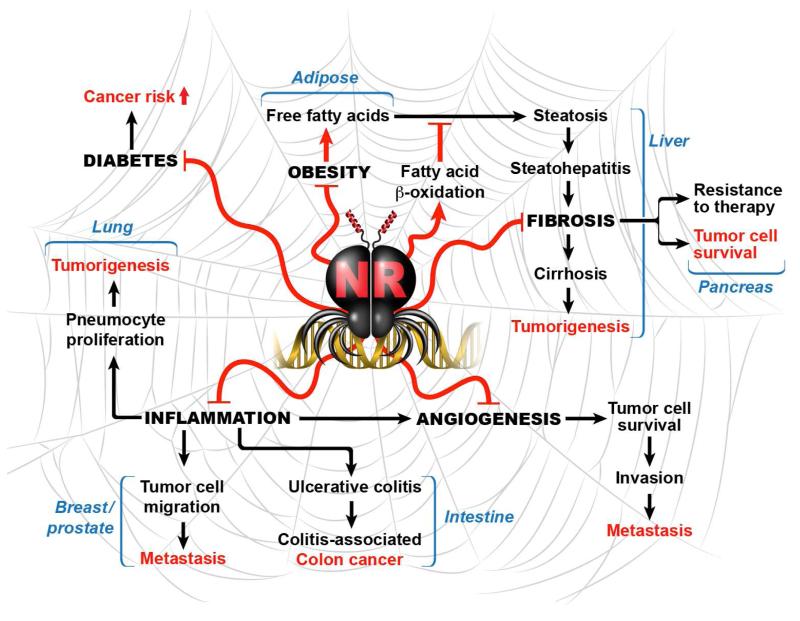

Figure 2.

Interrelatedness of nuclear receptors and physiologic or pathologic processes connected to cancer.

In the context of breast cancer, stromal tissue also contributes to tumorigenesis, and therefore represents a potentially important therapeutic target. In particular, stromal adipose tissue-produced estrogen plays a key role in breast tumor development and progression, highlighting the importance of communications between stromal tissue and tumor cells in the breast cancer microenvironment. The enzyme aromatase (CYP19) catalyzes the synthesis of estrogens from androgenic precursors, and aromatase is expressed in various tissues including ovary, placenta, bone, brain, and adipose tissue. Aromatase expression in these different tissues is under the control of tissue-specific promoters and is differentially regulated by various transcription factors46. In patients with breast cancer, estrogen levels within the breast tissue are substantially higher than serum levels, indicating local synthesis and accumulation of estrogens that can drive breast cancer growth47. As such, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) have become widely used therapeutic agents to prevent the progression or recurrence of breast cancer after primary therapy48—however, as AIs act to inhibit estrogen synthesis globally, their use is associated with detrimental side effects in tissues which require estrogen for normal function, such as bone49. Selective compounds which inhibit aromatase expression in breast but permit estrogen synthesis at other sites are therefore desirable for breast cancer therapy. Several NR ligands have been shown to inhibit the aromatase promoter in a tissue-specific manner. Ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) such as thiazolidinediones (TZDs)50, and for retinoid X receptor (RXR) such as the synthetic ligand LG10130551, have been shown to inhibit the aromatase promoter in breast adipose stromal tissue. These compounds exhibit specificity for aromatase promoter II, a critical regulatory region in mammary adipose tissue, over the bone-specific promoter I.451. The VDR ligand calcitriol has also been shown to specifically inhibit the aromatase promoter in breast stromal adipose as well as breast cancer cells, while paradoxically increasing aromatase expression in bone52. Unlike breast cancer, the growth of prostate epithelial cells can be negatively impacted by estrogens, specifically ERβ activity has been shown to promote differentiation while opposing proliferating in the developing prostate53, and ERβ agonist has been shown to promote apoptosis in both the stroma and epithelium of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer, even in the context of androgen independence54. While the precise mechanisms remain to be determined, it was reported that the beneficial impact of ERβ on prostate cancer required intraprostatic stromal-epithelial cell signaling, suggesting the importance of the tumor microenvironment in harnessing the therapeutic value of ERβ ligand.

In addition to fibroblasts and adipose tissue, recent reports suggest that bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are recruited to the stroma of developing tumors55, where they have been shown to increase tumor incidence, size, and metastatic potential56. The molecular mediators of MSC-tumor cell communication are therefore intriguing targets for therapy. Among them, MSC-secreted chemokine CCL5 (also called RANTES) was shown to be required for MSC-induced effects on metastasis in breast cancer, though this depends upon breast cancer cell type57. Impairing the interaction between MSC-produced CCL5 and its receptor CCR5 on breast cancer cells may be an exciting avenue for treatment of metastatic disease. In investigations of their anti-inflammatory properties, several NRs including PPARγ58-60, PPARα61, and ER (α and β)62-64 have been shown to directly or indirectly inhibit CCL5 expression in various contexts. While NR expression profiling has not been performed on tumor-associated MSCs, the therapeutic targeting of these or other anti-inflammatory NRs might be helpful in disabling MSC-cancer cell communication that contributes to tumor growth and metastasis.

Angiogenesis

Neovasculaturization is required to provide tumors with essential nutrients, oxygen, and removal of metabolic waste. Endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to impair tumor growth, and NR ligands may serve as pharmacologic means to retard the angiogenic process. Indeed, agonists for VDR have been shown to inhibit tumor-induced angiogenesis in multiple cancers including colon65, lung66, prostate67, and skin68. Interestingly, VDR agonists induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in tumor-derived endothelial cells (TDECs), yet these effects are not observed in endothelial cells isolated from normal tissues or from Matrigel plugs69. These differential anti-proliferative effects are appealing from a therapeutic standpoint, and may be explained in part by epigenetic silencing of the vitamin D degrading enzyme CYP24A1 in TDECs70. Similarly, PPARα activation has been shown to inhibit tumor angiogenesis in a cancer cell non-autonomous manner by suppressing endothelial cell proliferation and VEGF production, and increasing expression of anti-angiogenic thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) and endostatin71. Likewise, inhibitors of NOX1, an enzyme which generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), have been shown to block tumor angiogenesis in a PPARα-dependent manner72. PPARγ activation has also been shown to oppose endothelial cell proliferation and inhibit angiogenesis in multiple cancer types via both cancer cell autonomous functions, such as promoting cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis, and cancer cell non-autonomous functions including inhibition of angiogenesis-promoting factors COX-2, VEGF, and bFGF73. These findings in the context of tumor angiogenesis are particularly interesting given that both PPARα and PPARγ have established pro-angiogenic function in cardiovascular disease and diabetes74, highlighting the context dependence of NR ligands and their physiologic outcomes. Ligands for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) have also been shown to inhibit tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo, both by decreasing VEGF and IL-8 production by tumor cells75, leading to decreased microvessel density in vivo, and by blocking tube-like structure formation by vascular endothelial cells76. These findings led in part to the development of a phase 2 clinical trial of combined treatment with the GR ligand dexamethasone and the VDR ligand calcitriol for castration-resistant prostate cancer77, as anti-angiogenic agents had previously yielded some of the most promising results for these patients with otherwise limited treatment options78. While the trial failed to produce a clinical response, alterations to therapeutic delivery, including the use of liposomal glucocorticoids79, are currently under investigation and have yielded some promising results. Collectively, these findings point to NRs and their ligands as context-dependent anti-angiogenic agents which may be beneficial in inhibiting tumor-associated neovascularization.

Inflammation and immune surveillance

Infiltrating cells of the immune system serve both tumor-antagonizing and tumor-promoting roles in the tumor microenvironment. Targeting NRs may be of value in both the activation of tumor cell killing responses and inhibition of tumor-promoting inflammation. PPARγ, for example, has widespread anti-inflammatory roles in the immune system and has long been appreciated as a negative regulator of activation of monocytes80, macrophages81, and T lymphocytes82. As these immune cell types play key roles in cancer-associated inflammation, PPARγ is regarded as a promising novel agent to target inflammatory pathways in epithelial malignancies83. In addition to suppressing tumor-promoting inflammation, PPARγ may also serve to promote tumor-antagonizing immune function based on its established function in non-cancer contexts. Recent work has shown that PPARγ activation in dendritic cells coordinately regulates the CD1 cell surface glycoproteins, which are responsible for the presentation of self and foreign modified lipids. Specifically, PPARγ activation leads to a reduction in CD1a levels and an increase in expression of CD1d, which in turn promotes the selective induction of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell expansion84. These interferon-gamma (IFNγ)-producing iNKT cells have been shown to promote tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell responses85, though a direct connection between PPARγ activation and iNKT cell-mediated antitumor toxicity has not been demonstrated. Another NR, retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt), has been shown to play a critical role in the differentiation of NKp46+ lymphoid tissue-inducer (LTi) cells86. LTi cells in turn produce IL-12, which induces expression of adhesion molecules within tumor-associated vessels and promotes the invasion of leukocytes into the tumor87. RORγ also directs the differentiation of T helper 17 (TH17) cells, which display both anti-tumorigenic activities in certain contexts88. Retinoic acid has been shown to reciprocally inhibit TH17 cell differentiation and promote T regulatory (Treg) cell differentiation by inhibiting expression of RORγt89. Treg cells have also been shown to suppress antitumor immunity90. As such, compounds with the opposite effect, which promote RORγt expression and/or function, may also help to tip the immunological balance toward antitumor immunity. The broad anti-inflammatory functions of other NRs make them appealing therapeutic targets in the tumor microenvironment. Using a systems biology approach VDR, for example, was identified as the best candidate master regulator of a genetic network that suppresses both inflammation and promotes tissue barrier function91, leading to a predicted decrease in cancer susceptibility in skin. A connection between the anti-inflammatory function of VDR and decreased cancer risk has been demonstrated in other tissues as well, such as colon92 and prostate93, and while VDR expression in a number of immune cell types has been demonstrated, the precise cell types and mechanisms important for this VDR-mediated anti-inflammatory function remain to be determined. Taken together, the established roles of NRs in various cell types of the immune system point to several avenues for therapeutic potential in the tumor microenvironment.

Concluding remarks

In this review, we highlight recent findings which reveal the therapeutic promise of NRs and their ligands in various cell types of importance to tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Beyond this simplified discussion, evidence exists for tumor-promoting roles of NRs in certain tissues or tumor types, suggesting that the therapeutic potential of any NR ligand is likely to be highly context-specific. The interrelatedness of inflammation, epithelial integrity, and tumor susceptibility is increasingly appreciated, and evidence for this stems in part from the increased risk for cancer development among patients with chronic inflammatory diseases. NRs have established beneficial roles in a number of these diseases which predispose to cancer, including diabetes, obesity, ulcerative colitis, hepatic fibrosis, and others (Figure 2). This suggests that, in addition to the potential use of NR ligands in combinatorial cancer therapies, these drugs may be of great value as preventative measures against cancer development within high-risk populations.

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Ong and S. Ganley for administrative assistance. Chris Liddle for useful discussion. R.M.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology at the Salk Institute. Mara Sherman is supported by a NIH T32 training grant CA009370. This work was supported, in part by grants from the American Association for Cancer Research/Stand Up to Cancer Dream Team Translational Cancer Research Grant, Ipsen/Biomeasure, The Helmsley Charitable Trust, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, National Institutes of Health (DK062434, DK090962) and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project Grant 512354.

References

- 1.Polyak K, Haviv I, Campbell IG. Co-evolution of tumor cells and their microenvironment. Trends Genet. 2009;25:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:924–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:119–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pietras K, Ostman A. Hallmarks of cancer: interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhowmick NA, et al. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303:848–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng N, Chytil A, Shyr Y, Joly A, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling-deficient fibroblasts enhance hepatocyte growth factor signaling in mammary carcinoma cells to promote scattering and invasion. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1521–33. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumour-host interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–9. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pupa SM, Menard S, Forti S, Tagliabue E. New insights into the role of extracellular matrix during tumor onset and progression. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:259–67. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiseman BS, Werb Z. Stromal effects on mammary gland development and breast cancer. Science. 2002;296:1046–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1067431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baeriswyl V, Christofori G. The angiogenic switch in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergers G, Song S. The role of pericytes in blood-vessel formation and maintenance. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:452–64. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fridlender ZG, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sica A, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Cancer related inflammation: the macrophage connection. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:204–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonoda J, Pei L, Evans RM. Nuclear receptors: decoding metabolic disease. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans R. A transcriptional basis for physiology. Nat Med. 2004;10:1022–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1004-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–95. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bookout AL, et al. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126:789–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barish GD, et al. A Nuclear Receptor Atlas: macrophage activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2466–77. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenna NJ, et al. Minireview: Evolution of NURSA, the Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:740–6. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergers G. Benjamin, L. E. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyberg P, Xie L, Kalluri R. Endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3967–79. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Patrono C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as anticancer agents: mechanistic, pharmacologic, and clinical issues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:252–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothwell PM, et al. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.French RR, Chan HT, Tutt AL, Glennie MJ. CD40 antibody evokes a cytotoxic T-cell response that eradicates lymphoma and bypasses T-cell help. Nat Med. 1999;5:548–53. doi: 10.1038/8426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diehl L, et al. CD40 activation in vivo overcomes peptide-induced peripheral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte tolerance and augments anti-tumor vaccine efficacy. Nat Med. 1999;5:774–9. doi: 10.1038/10495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sotomayor EM, et al. Conversion of tumor-specific CD4+ T-cell tolerance to T-cell priming through in vivo ligation of CD40. Nat Med. 1999;5:780–7. doi: 10.1038/10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beatty GL, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loeffler M, Kruger JA, Niethammer AG, Reisfeld RA. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1955–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI26532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraman M, et al. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha. Science. 2010;330:827–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1195300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vonlaufen A, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells and pancreatic cancer cells: an unholy alliance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7707–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Omary MB, Lugea A, Lowe AW, Pandol SJ. The pancreatic stellate cell: a star on the rise in pancreatic diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:50–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI30082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olive KP, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wehr AY, Furth EE, Sangar V, Blair IA, Yu KH. Analysis of the human pancreatic stellate cell secreted proteome. Pancreas. 2011;40:557–66. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318214efaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Froeling FE, et al. Retinoic Acid-Induced Pancreatic Stellate Cell Quiescence Reduces Paracrine Wnt-beta-Catenin Signaling to Slow Tumor Progression. Gastroenterology. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abramovitch S, et al. Vitamin D inhibits proliferation and profibrotic marker expression in hepatic stellate cells and decreases thioacetamide-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Gut. 2011 doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson ER, et al. Aromatase--a brief overview. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:93–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081601.142703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brodie A, Long B, Lu Q. Aromatase expression in the human breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;49(Suppl 1):S85–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1006029612990. discussion S109-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geisler J, Lonning PE. Aromatase inhibition: translation into a successful therapeutic approach. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2809–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mincey BA, et al. Risk of cancer treatment-associated bone loss and fractures among women with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors. Clin Breast Cancer. 2006;7:127–32. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubin GL, Zhao Y, Kalus AM, Simpson ER. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands inhibit estrogen biosynthesis in human breast adipose tissue: possible implications for breast cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1604–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubin GL, et al. Ligands for the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the retinoid X receptor inhibit aromatase cytochrome P450 (CYP19) expression mediated by promoter II in human breast adipose. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2863–71. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishnan AV, et al. Tissue-selective regulation of aromatase expression by calcitriol: implications for breast cancer therapy. Endocrinology. 2010;151:32–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Imamov O, et al. Estrogen receptor beta regulates epithelial cellular differentiation in the mouse ventral prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9375–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McPherson SJ, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta activated apoptosis in benign hyperplasia and cancer of the prostate is androgen independent and TNFalpha mediated. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905524107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall B, Andreeff M, Marini F. The participation of mesenchymal stem cells in tumor stroma formation and their application as targeted-gene delivery vehicles. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007:263–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68976-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klopp AH, Gupta A, Spaeth E, Andreeff M, Marini F., 3rd Concise review: Dissecting a discrepancy in the literature: do mesenchymal stem cells support or suppress tumor growth? Stem Cells. 2011;29:11–9. doi: 10.1002/stem.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karnoub AE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–63. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cha B, Lim JW, Kim KH, Kim H. 15-deoxy-D12,14-prostaglandin J2 suppresses RANTES expression by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activation in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:167–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu M, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of thiazolidinediones in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:111–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0445OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gosset P, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators affect the maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2857–65. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2857::aid-immu2857>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitajima K, Miura S, Mastuo Y, Uehara Y, Saku K. Newly developed PPAR-alpha agonist (R)-K-13675 inhibits the secretion of inflammatory markers without affecting cell proliferation or tube formation. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown CM, Mulcahey TA, Filipek NC, Wise PM. Production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines during neuroinflammation: novel roles for estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4916–25. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanda N, Watanabe S. 17beta-estradiol inhibits the production of RANTES in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:420–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evans MJ, Eckert A, Lai K, Adelman SJ, Harnish DC. Reciprocal antagonism between estrogen receptor and NF-kappaB activity in vivo. Circ Res. 2001;89:823–30. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.098543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pendas-Franco N, et al. DICKKOPF-4 is induced by TCF/beta-catenin and upregulated in human colon cancer, promotes tumour cell invasion and angiogenesis and is repressed by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Oncogene. 2008;27:4467–77. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakagawa K, Sasaki Y, Kato S, Kubodera N, Okano T. 22-Oxa-1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits metastasis and angiogenesis in lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1044–54. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishnan AV, Peehl DM, Feldman D. The role of vitamin D in prostate cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003;164:205–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55580-0_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Majewski S, et al. Vitamin D3 is a potent inhibitor of tumor cell-induced angiogenesis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1996;1:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chung I, et al. Differential antiproliferative effects of calcitriol on tumor-derived and matrigel-derived endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8565–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chung I, et al. Epigenetic silencing of CYP24 in tumor-derived endothelial cells contributes to selective growth inhibition by calcitriol. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8704–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Panigrahy D, et al. PPARalpha agonist fenofibrate suppresses tumor growth through direct and indirect angiogenesis inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:985–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711281105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garrido-Urbani S, et al. Targeting vascular NADPH oxidase 1 blocks tumor angiogenesis through a PPARalpha mediated mechanism. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panigrahy D, Huang S, Kieran MW, Kaipainen A. PPARgamma as a therapeutic target for tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:687–93. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.7.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Fonseca V. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors as stimulants of angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2009;2:165–72. doi: 10.2147/dmsott.s4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yano A, Fujii Y, Iwai A, Kageyama Y, Kihara K. Glucocorticoids suppress tumor angiogenesis and in vivo growth of prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3003–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Logie JJ, et al. Glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of angiogenic changes in human endothelial cells is not caused by reductions in cell proliferation or migration. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chadha MK, et al. Phase 2 trial of weekly intravenous 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) in combination with dexamethasone for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:2132–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merino M, Pinto A, Gonzalez R, Espinosa E. Antiangiogenic agents and endothelin antagonists in advanced castration resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1846–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Banciu M, Metselaar JM, Schiffelers RM, Storm G. Liposomal glucocorticoids as tumor-targeted anti-angiogenic nanomedicine in B16 melanoma-bearing mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;111:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–6. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang XY, et al. Activation of human T lymphocytes is inhibited by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) agonists. PPARgamma co-association with transcription factor NFAT. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4541–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Demaria S, et al. Cancer and inflammation: promise for biologic therapy. J Immunother. 2010;33:335–51. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181d32e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Szatmari I, et al. Activation of PPARgamma specifies a dendritic cell subtype capable of enhanced induction of iNKT cell expansion. Immunity. 2004;21:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moreno M, et al. IFN-gamma-producing human invariant NKT cells promote tumor-associated antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell responses. J Immunol. 2008;181:2446–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanos SL, et al. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eisenring M, vom Berg J, Kristiansen G, Saller E, Becher B. IL-12 initiates tumor rejection via lymphoid tissue-inducer cells bearing the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1030–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zou W, Restifo NP. T(H)17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:248–56. doi: 10.1038/nri2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mucida D, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smyth MJ, et al. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells suppress NK cell-mediated immunotherapy of cancer. J Immunol. 2006;176:1582–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Quigley DA, et al. Genetic architecture of mouse skin inflammation and tumour susceptibility. Nature. 2009;458:505–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Appleyard CB, et al. Pretreatment with the Probiotic Vsl#3 Delays Transition from Inflammation to Dysplasia in a Rat Model of Colitis-Associated Cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00167.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adorini L, et al. Inhibition of prostate growth and inflammation by the vitamin D receptor agonist BXL-628 (elocalcitol) J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:689–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]