Summary

Osteoblasts are an important component of the hematopoietic microenvironment in bone. However, the mechanisms by which osteoblasts control hematopoiesis remain unknown. We show that augmented HIF signaling in osteoprogenitors results in HSC niche expansion associated with selective expansion of the erythroid lineage. Increased red blood cell production occurred in an EPO-dependent manner with increased EPO expression in bone and suppressed EPO expression in the kidney. In contrast, inactivation of HIF in osteoprogenitors reduced EPO expression in bone. Importantly, augmented HIF activity in osteoprogenitors protected mice from stress-induced anemia. Pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of prolyl hydroxylases1/2/3 in osteoprogenitors was elevated EPO expression in bone and increased hematocrit. These data reveal an unexpected role for osteoblasts in the production of EPO and modulation of erythropoiesis. Furthermore, these studies demonstrate a molecular role for osteoblastic PHD/VHL/HIF signaling that can be targeted to elevate both HSCs and erythroid progenitors in the local hematopoietic microenvironment.

Introduction

The bone marrow is a complex and dynamic microenvironment with multiple cells types contributing to “niches” that support HSCs, myelopoiesis, and lymphopoiesis in the bone marrow (Calvi et al., 2003; Kiel et al., 2005; Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010). Among these cell types, osteoblasts play in important role in regulating multiple hematopoietic lineages. Conditional ablation of osteoblasts in adult mice showed that osteoblasts are required to maintain hematopoiesis in the bone marrow. An early loss of hematopoietic stem cells as well as committed progenitor cells of the B-lymphocyte and erythroid lineages indicated that osteoblasts contribute to the regulation of multiple hematopoietic lineages (Visnjic et al., 2004). Several groups have shown a correlation between osteoblast and HSC numbers in the bone marrow (Calvi et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). Additionally, osteoblasts directly regulate the maturation and differentiation of B-lymphocytes (Wu et al., 2008). Whether osteoblasts directly or indirectly contribute to the regulation of erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow remains unknown. In addition to playing a physiologic role in the regulation of hematopoiesis, osteoblasts have also been identified as an important therapeutic target for stem cell based therapies (Adams et al., 2007). However, little is known regarding the mechanisms by which osteoblasts support hematopoiesis. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing osteoblastic control of hematopoiesis will allow for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of hematologic disorders.

Osteoblasts express components of the HIF signaling pathway under physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions indicating that HIF signaling is an important mediator of normal osteoblast function and disease. The central components of the HIF signaling pathway are the prolyl hydroxylase enzymes 1, 2, and 3 (PHD1/2/3), VHL, HIF-1, and HIF-2. The PHDs and VHL negatively regulate the pathway under normoxic conditions by cooperatively targeting hypoxia inducible transcription factors HIF-1 and HIF-2 for proteasomal degradation (Semenza, 2001). Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1 and HIF-2 are stabilized and coordinate the cellular response to hypoxia by activating gene expression programs that facilitate oxygen delivery and cellular adaptation to oxygen deprivation (Semenza, 2001). In addition to hypoxia, growth factor signaling also activates HIF activity in osteoblasts through the PI3K/AKT pathway (Akeno et al., 2002). In many cell types, activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway increases HIF activity in an mTOR dependent manner that is thought to have both transcriptional and post-translational effects on HIF. Thus, multiple stimuli activate HIF signaling in to maintain cellular survival and homeostasis under stress conditions.

HIF signaling in osteoblasts plays an important role in bone formation and homeostasis. Conditional ablation of HIF-1 and HIF-2 in osteoblasts causes a reduction in bone volume, whereas HIF-1 and HIF-2 overstabilization leads to an increase in bone mass. The changes in bone volume were largely associated with modulation of bone vascularization and VEGF expression revealing an important role for HIF signaling in osteoblasts in coupling osteogenesis with angiogenesis (Wang et al., 2007).

HIF signaling also regulates hematopoiesis. Hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) metabolism is dependent on glycolysis. This process is regulated at least in part through the transcriptional activation of Meis1 by HIF-1 (Simsek et al., 2010). Additionally, dysregulation of HIF-1 affects HSC cell cycle quiescence and numbers. Deletion of HIF-1 in HSCs resulted in a loss of HSC quiescence and numbers during stress conditions demonstrating a direct role for HIF in the regulation of HSCs (Takubo et al., 2010). HIF signaling also regulates mature hematopoietic lineages. Most notably, HIF-1 was purified as the factor responsible for the hypoxic induction of EPO and regulates erythropoiesis during development and under stress (Semenza and Wang, 1992; Yoon et al., 2006; Yu et al., 1999). In addition to HIF-1, HIF-2 also regulates EPO in adult mice (Haase, 2010). HIF-1 and HIF-2 control EPO expression in the fetal liver and kidney to promote erythroid progenitors cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation (Haase, 2010). Additionally, HIF signaling directly promotes erythroid progenitor survival (Flygare et al., 2011).

Here we have utilized genetic and pharmacologic mouse models of constitutive HIF activation and inactivation in osteoprogenitor cells to investigate the role of HIF signaling in osteoblastitc control of hematopoiesis. We show that osteoblasts produce EPO through a HIF dependent mechanism under physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, we found that modulation of the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway in osteoblasts is sufficient to induce EPO in bone, elevate hematocrit, and protect mice from stress-induced anemia. Additionally, augmented HIF activity in osteoblasts increases functional hematopoietic stem cells and early progenitors in the bone marrow. These data reveal osteoblasts as an previously unsuspected source of endogenous EPO and identify the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway in osteoblasts as a therapeutic target to elevate EPO and HSCs in the local hematopoietic microenvironment.

Results

Generation of Mice with HIF-1 and HIF-2 Overstabilization and Inactivation in Osteoprogenitor Cells

Osteoblasts are an essential component of bone and the bone marrow microenvironment for the regulation of skeletal and hematopoietic homeostasis. They express two HIF-α homologs (HIF-1α and HIF-2α) that have been previously shown to regulate HIF target gene expression and control skeletal homeostasis (Wang et al., 2007). In order to define the role of HIF signaling in osteoblasts in the regulation of hematopoiesis, we conditionally inactivated VHL, HIF-1, and HIF-2 in osteoprogenitor cells. For this purpose, mice homozygous for the VHL, HIF-1, and HIF-2 conditional alleles (2-lox) were crossed to mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the control of the osterix promoter (OSX-Cre) to generate OSX-VHL and OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mice (Gruber et al., 2007; Haase et al., 2001; Rodda and McMahon, 2006; Ryan et al., 1998).

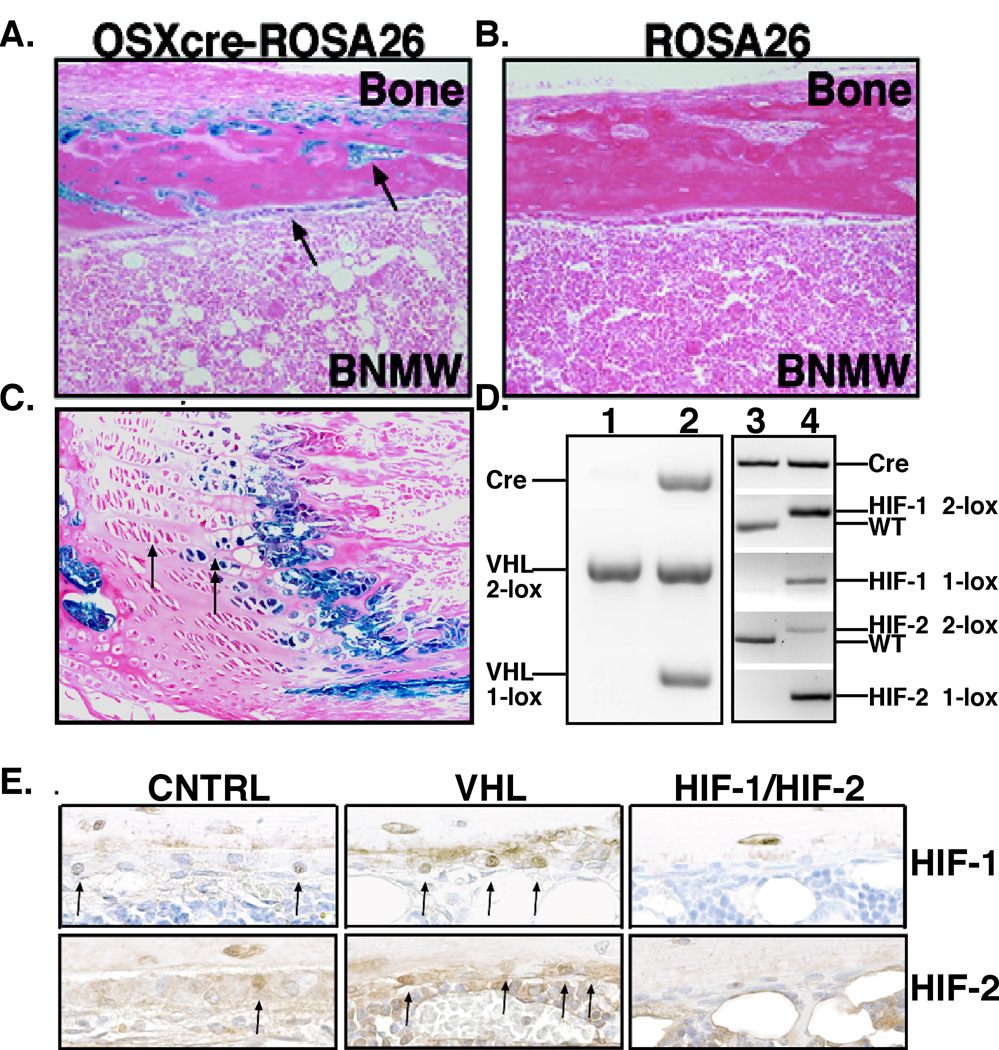

Osterix-Cre is a well-characterized transgene that mediates efficient Cre-recombinase activity in osteoprogenitor cells, thereby targeting the entire osteoblastic lineage (Rodda and McMahon, 2006). The specificity of OSX-Cre in adult bone was confirmed using ROSA-LacZ reporter mice. Specific β-galactosidase activity was found in all cells of the osteoblastic lineage including endosteal osteoblasts, osteoblasts, and stromal cells located at the chondro-osseous junction (Figure 1A–C). As previously reported, OSX-Cre activity was also found in a subset of hypertrophic and columnar chondrocytes (Figure 1C) (Maes et al., 2010b). Most importantly, OSX-Cre activity was absent from all hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Generation of mice deficient for VHL or HIF-1 and HIF-2 in osteoblasts.

A–C. ROSA-LacZ reporter expression of Osterix-Cre (A–B) in 8-week-old mouse tibia. Arrows in (A) point to osteoblasts at the endosteal bone surface and embedded in cortical bone with B-galactosidase activity. B. Shows the absence of detectable B-galactosidase activity in ROSA-LacZ mice without OSX-Cre. C. Arrows point to subset of hypertrophic chondrocytes expressing B-galactosidase activity. D. Efficient recombination of the VHL, HIF-1, and HIF-2 alleles in the bone of Osterix-Cre mutant mice. PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from bone of 1) OSX-Cre control, 2) OSX-VHL, 3) OSX-Cre control, and 4) OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mice. Abbreviations: conditional allele, 2-lox; recombined allele, 1-lox; and wild-type allele, WT. E. Immunohistochemical analysis of HIF-1 (top) and HIF-2 (bottom) expression in OSX-Cre tibias. Arrows point to osteoblasts expressing HIF-1 or HIF-2.

Osterix-Cre mediates efficient recombination of the VHL, HIF-1 and HIF-2 conditional alleles. The VHL conditional allele contains LoxP sites flanking the Vhlh promoter and exon 1 resulting in complete loss of VHL expression and HIF overstabilization upon Cre-mediated recombination (Haase et al., 2001). Efficient recombination of the VHL conditional allele in OSX-VHL tibiae was observed by genomic PCR analysis for the recombined (1-lox) allele (Figure 1D). Consistent with VHL inactivation, we observed an increase in the number of osteoblasts and the intensity of nuclear HIF-1 and HIF-2 expression in OSX-VHL tibias by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 1E). The conditional alleles for HIF-1 and HIF-2 contain Lox-P sites flanking exon 2 (encodes the DNA binding domain) resulting in an out-of-frame deletion of exon 2 and loss of HIF-1 and HIF-2 expression following Cre recombination (Gruber et al., 2007; Ryan et al., 1998). Osterix-Cre mediated recombination of the HIF-1 and HIF-2 conditional alleles was readily detectable in adult OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 tibias and resulted in a reduction of HIF-1 and HIF-2 protein in osteoblasts (Figure 1D–E).

Augmented HIF Activity in Osteoprogenitors Expands the HSC Niche in the Bone Marrow

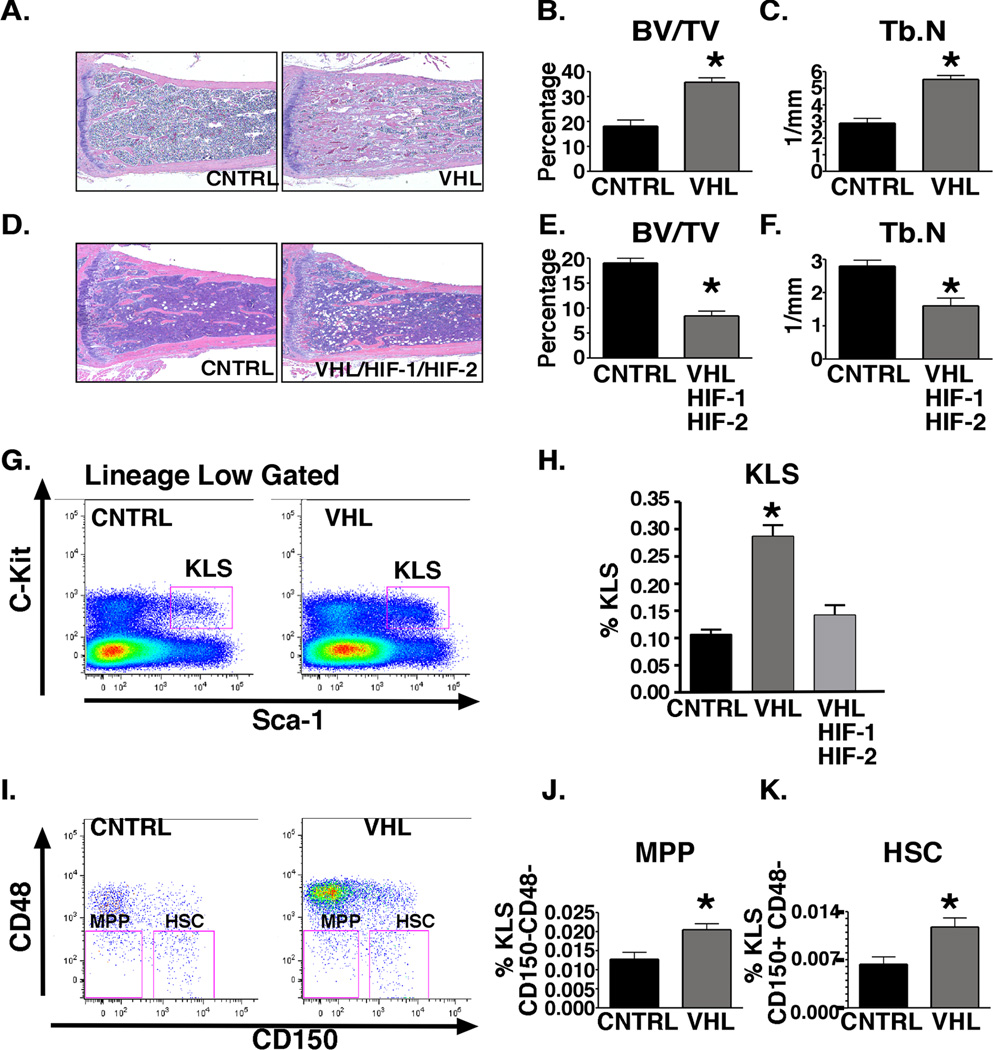

Previous reports have demonstrated that osteoblasts are a critical component of the HSC niche. Specifically, an increase in trabecular osteoblastic cells and trabeculae are associated with an increase in HSCs (Calvi et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). Therefore, we first analyzed the functional consequences of HIF-1 and HIF-2 overstabilization on trabecular bone and HSC homeostasis. OSX-VHL mutant mice exhibited excessive accumulation of trabecular bone in the metaphyseal and diaphyseal regions of the long bones (Figure 2A). Increased trabeculae were associated with increased trabecular osteoblasts as indicated by increased expression of the osteoblastic marker collagen type I throughout the long bone (Figure S1A). Stromal cells and dilated blood vessels filled with red blood cells surrounded the trabeculae (Figure 2A). Hypervascularization in OSX-VHL mutant bones was apparent as staining for CD31 revealed an increase in blood vessels throughout the bone (Figure S1B). This increase in vascularization was associated with a significant increase in local VEGF production by osteoblasts (Figure S1C). However, circulating levels of VEGF in serum remained unaffected (Figure S1D). Histomorphometry revealed a 2.5 fold increase in trabecular bone volume in the metaphyseal region associated with an significant increase in trabecular number (Figure 2B–C). To determine whether HIF signaling in osteoblasts is required to maintain trabecular bone homeostasis in VHL deficient mice, we generated and analyzed OSX-VHL/HIF1/HIF2 triple knockout mice. In contrast to OSX-VHL mutants, OSX-VHL/HIF1/HIF2 mice had significantly reduced trabecular bone volume and number compared to littermate controls (Figure 2D–F). These data demonstrate that augmented HIF activity in osteoprogenitors expands trabecular bone volume associated with increased vascularization.

Figure 2. Augmented HIF activity in osteoblasts through VHL deletion expands the HSC niche.

A. Histological analysis of H&E stained OSX-Cre tibias at 8-weeks of age. B–C. Histomorphometric analysis of trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N) in tibia (n=6). D. H&E stained tibia at 8-weeks of age. E–F. Histomorphometric analysis of trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N) in OSX-Cre tibias (n=6). G. Flow cytometric analysis (FACS) of c-Kit+ Lineagelow Sca-1+ (KLS) progenitors in OSX-Cre bone marrow. H. Frequency of KLS in OSX-Cre mutant bone marrow shown as percentage of total bone marrow cells at 8-weeks-of age (K, n = 7 in each group). I. FACS analysis of multipotent progenitor (MPP) and KLS-SLAM (HSC) of 8-week-old OSX-Cre bone marrow. J. Frequency of MPPs in OSX-Cre bone marrow shown as percentage of total bone marrow cells. For each group analyzed n = 4. K. Frequency of HSCs in OSX-Cre bone marrow shown as percentage of total bone marrow cells. For each group analyzed n = 4. FACS experiments shown are a representative experiment in which littermate controls were directly compared to OSX-mutant mice. All experiments were independently performed at least three times. See also Figure S1. All data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

To determine whether HIF signaling in osteoprogenitors affects the composition of hematopoietic cells within the bone marrow, we first compared hematopoietic progenitor and HSC composition in 8-week-old OSX-Cre mutant mice. Because OSX-VHL mice were significantly smaller than littermate controls and total bone marrow cell numbers were decreased, the analysis of hematopoietic lineages in OSX-mutant mice is reported as percent frequency of bone marrow cells (data not shown). We analyzed the early KLS (cKit+, Lineage negative, Sca1+) progenitors that include HSCs and multipotent progenitors (MPP). Strikingly, the frequency of KLS cells within OSX-VHL bone marrow was increased 3-fold compared to littermate controls (Figure 2G–H). The frequency of KLS in OSX-VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2 mutants was comparable to OSX-CNTRL mutants demonstrating that KLS frequency in OSX-VHL bone marrow is controlled by HIF activity (Figure 2H). Within the KLS population of OSX-VHL mutants, we observed a significant increase in the frequency of both MPP (CD150−CD48−) and HSC (CD150+CD48−) populations (Figure 2I–K). These immunophenotypic findings suggest that VHL deletion and enhanced HIF activity in osteoprogenitor cells leads to an increased frequency of HSCs in the bone marrow.

To functionally test whether HSCs are increased in OSX-VHL bone marrow we performed long-term repopulation assays. Whole bone marrow from OSX-CNTRL or OSX-VHL mice (male FVB) was mixed 1:1 with wild type competitor marrow (female FVB) and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice (female FVB). The contribution to peripheral blood and B cells in the bone marrow was assessed at 20 weeks following transplantation. Real time PCR analysis of SRY chromosome expression revealed a significant increase in Y chromosome expression in both the peripheral blood and B220+ B cells from mice transplanted with OSX-VHL donor marrow compared to mice transplanted with OSX-CNTRL marrow (Figure S1E–F). Together, these findings indicate cells isolated from the VHL deficient bone marrow microenvironment contain an increased frequency of HSCs capable of reconstituting irradiated recipients.

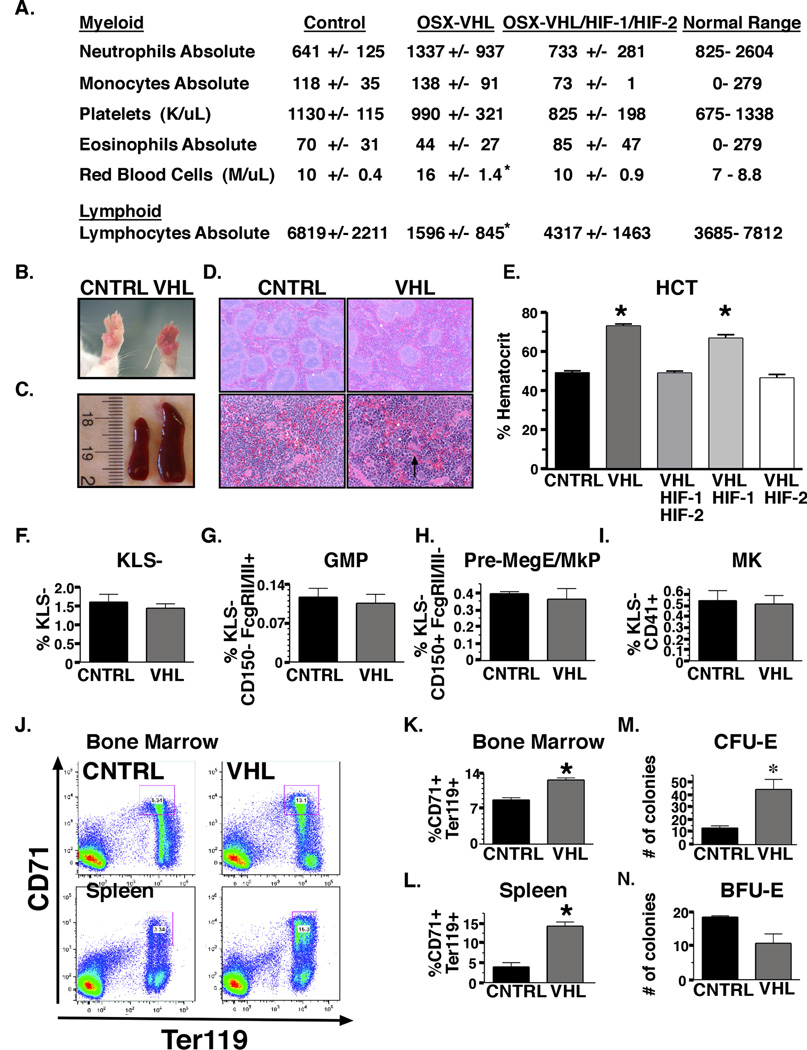

Selective expansion of the erythroid lineage in OSX-VHL mutant mice leads to the development of HIF-dependent polycythemia

We next examined whether augmented HIF signaling in osteoprogenitors affects the ability of osteoblasts to support mature blood lineages. We compared cells of the myeloid and lymphoid lineages in peripheral blood from 8-week-old mice OSX-Cre mutant mice. OSX-VHL mutant mice exhibited significant changes in the numbers of red blood cells and lymphocytes. Red blood cell numbers were increased from 10 +/− 0.4 in OSX-Controls to 16 +/− 1.4 in OSX-VHL mice, whereas lymphocyte numbers were decreased from 6,819 +/− 2211 in controls to 1,596 +/− 845 in OSX-VHL mutants (Figure 3A). Increased RBC and decreased lymphocyte numbers in OSX-VHL mutant mice were HIF dependent as OSX-VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2 mutants had similar numbers of RBCs and lymphocytes compared to OSX-Control mice (Figure 3A). These data reveal that osteoblastic HIF affects both erythroid and lymphoid homeostasis.

Figure 3. Selective expansion of the erythroid lineage in OSX-VHL mice leads to the development of HIF-dependent polycythemia.

A. CBC analysis of peripheral blood from 8-week-old OSX-Cre mutant mice (n = 8 for all groups expect n = 6 for OSX-VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2). B. Photograph of 8-week-old OSX-VHL and littermate control (OSX-CNTRL) paws. C. Photograph of spleens collected from 8-week-old OSX-CNTRL (left) and OSX-VHL (right) mice. D. Histological analysis of spleen from OSX-Cre mice at 40X (top) and 200X (bottom). E. Average hematocrit (HCT) of OSX-Cre mice at 8-weeks-of age ( CNTRL, n = 8; VHL, n = 8; VHL/HIF-1, VHL/HIF-2, VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2, n = 6). F–I. Frequency of myeloid progenitor KLS− (cKithigh Lineagelow Sca1−); granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP, KLS− FcgRII/IIIhigh CD150−); Pre-megakaryocyte-erythroid, Pre-erythroid, megakaryocyte (Pre MegE/MkP/Pre CFU-E, KLS− FcgRII/IIIlow CD150+) and mature megakaryocyte (Mk, KLS− CD41+) cells within OSX-CNTRL and OSX-VHL bone marrow ( n = 4 for all groups). J. FACS analysis of erythroid lineage CD71+ Ter119+ in bone marrow and spleen of OSX-Cre mice. K–L. Significant increase in the frequency of erythroid progenitors in OSX-VHL mutant bone marrow (F, n = 4 in each group) and spleen (G, n = 3 in each group) as determined by FACS analysis. M–N. Quantification of CFU-E ( n = 5) and BFU-E ( n = 3) colonies in the bone marrow of OSX-mice. FACS experiments shown are a representative experiment in which littermate controls were directly compared to OSX-mutant mice. All experiments were independently performed at least three times. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

Given that a direct role for osteoblasts in the regulation of erythropoiesis has not been previously reported, we sought to further investigate the role of the HIF signaling pathway osteoblasts for the regulation of erythropoiesis. One hundred percent of OSX-VHL mutant developed severe polycythemia by 2 months of age. Polycythemia in OSX-VHL mice was characterized by redness of the paws, splenomegaly, extramedullary erythropoiesis, elevated hematocrit (avg. 73% compared to 45% in controls) and red blood cell numbers (Figure 3A–E). To examine whether the development of polycythemia in OSX-VHL mice was HIF-1 and/or HIF-2 dependent, we analyzed OSX-VHL/HIF-1, OSX-VHL/HIF-2, and OSX-VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2 mice. Hematocrit values in OSX-VHL/HIF-2 and OSX-VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2 mice were indistinguishable from controls, whereas OSX-VHL/HIF-1 mutants exhibited a similar increase in hematocrit (70%) compared to OSX-VHL mutants (Figure 3E). These data show that augmented HIF-2 signaling in osteoprogenitor cells leads to the development of polycythemia.

To examine the mechanisms for HIF mediated polycythemia in OSX-VHL mutants, we performed a detailed analysis of the myeloerythroid compartment in OSX-VHL bone marrow (Pronk et al., 2007). Flow-cytometric analysis showed no significant difference in myeloid progenitor KLS− (cKithigh Lineagelow Sca1−); granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP, KLS− FcgRII/IIIhigh CD150−); Pre-megakaryocyte-erythroid, Pre-erythroid, megakaryocyte (Pre MegE/MkP/Pre CFU-E, KLS− FcgRII/IIIlow CD150+) or mature megakaryocyte (Mk, KLS− CD41+) cells within OSX-VHL bone marrow (Figure 3F–I). In contrast, CD71+ Ter119+ erythroid progenitors were significantly increased in OSX-VHL bone marrow (1.4 fold) and spleen (4 fold, Figure 3J–L). Consistent with the immunophenotyping results, hematopoietic progenitor colony assays showed a significant and specific increase in mature erythroid (CFU-E) compared to immature erythroid (BFU-E) progenitors in OSX-VHL bone marrow (Figure 3M–N) (Wu et al., 1995). These results demonstrate that VHL deletion in osteoprogenitors causes a specific expansion of the erythroid lineage.

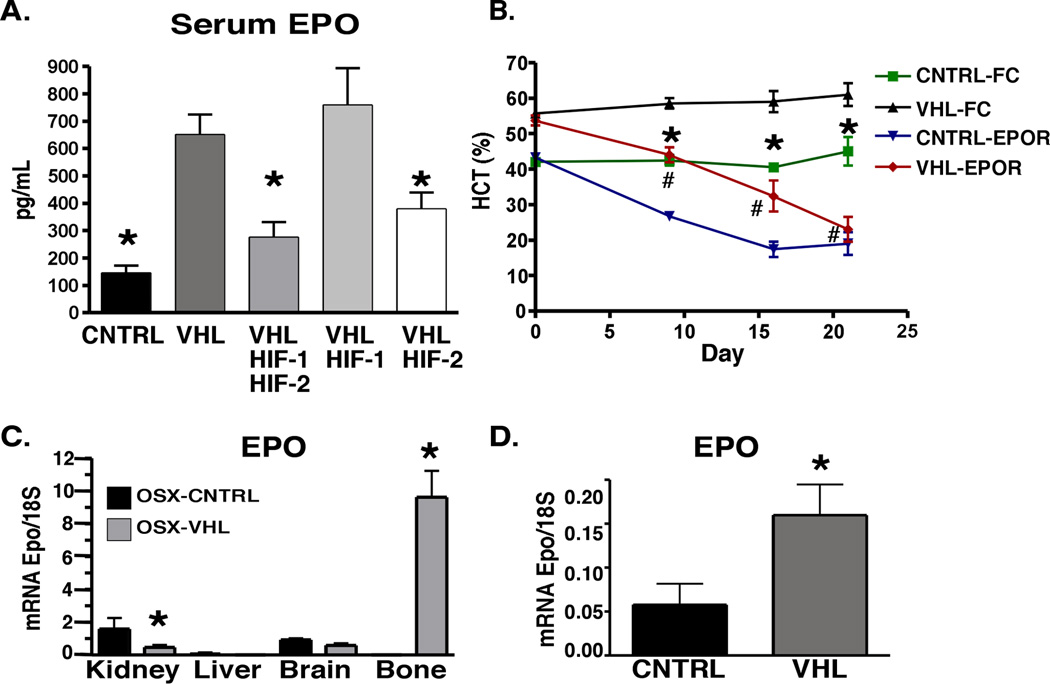

Increased hematocrit in OSX-VHL mice is EPO-dependent and associated with increased EPO expression in bone and decreased EPO expression in the kidney

The glycoprotein EPO is the primary hormone responsible for the regulation of erythropoiesis. Clinically EPO overproduction results in the development of polycythemia. EPO protein levels were significantly increased in the sera from polycythemic OSX-VHL and OSX-VHL/HIF-1 mice compared to EPO levels in littermate control mice (Figure 4A). Inactivation of HIF-1/HIF-2 or HIF-2, but not HIF-1, in OSX-VHL mice significantly reduced EPO levels demonstrating that HIF-2 is the predominant HIF required for dysregulated EPO production in OSX-VHL mice (Figure 4A). Thus, augmented HIF-2 signaling in osteoprogenitor cells leads to polycythemia associated with elevated circulating EPO.

Figure 4. Increased hematocrit in OSX-VHL mice develops in an EPO-dependent manner associated with increased EPO expression in bone and decreased EPO expression in the kidney.

A. Analysis of EPO protein levels in the serum of 2-month old OSX-mice determined by ELISA (CNTRL, VHL/HIF-1, VHL/HIF-2, and VHL/HIF-1/HIF-2, n = 6; VHL, n = 8). B. Soluble EPO-receptor therapy (EPOR) significantly reduces hematocrit in OSX-VHL mice. Average hematocrit of 6.5 week old OSX-Cre mice treated with adenovirus expressing FC control or soluble Epo-receptor (EPO-R). Statistical significant differences (p<0.05) in hematocrit were observed between VHL-FC and CNTRL-FC (*) treated mice as well as VHL-FC and VHL-EPOR (#) treated mice (n = 4 each group). C. Real time PCR analysis of EPO mRNA expression in tissues collected from 8-week-old OSX-Cre mice (n = 3 mice per group). D. Real time PCR analysis of EPO expression in bone marrow stromal cells isolated from OSX-Cre hindlimbs (n = 3 mice per group). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. See also Figure S2.

To determine whether the development of polycythemia in OSX-VHL mutant mice is EPO dependent, we utilized a soluble EPO-receptor therapy to block the functional activity of circulating EPO. Soluble EPO-receptor therapy was delivered using an adenoviral system in which the liver produces systemic soluble EPO-receptor that effectively decreases hematocrit in polycythemic mice for up to 28 days following tail vein injection (Tam et al., 2006). When administered to OSX-VHL mutants at 6.5 weeks of age, EPO-receptor therapy completely prevented the development of polycythemia in OSX-VHL mutants. While OSX-VHL FC control treated mice exhibited significantly elevated hematocrit (55–60%) compared to OSX-CNTRL FC treated mice (41%), soluble receptor therapy significantly decreased hematocrit both in OSX-VHL mice (22%) and OSX-CNTRL mice (20%) after 21 days of therapy (Figure 4B). Accordingly, the decrease in hematocrit in OSX-VHL EPO-R treated mice was associated with a significant decrease in CD71+ Ter119+ erythroid progenitors in the spleen compared to OSX-VHL FC-Control treated mice (Figure S2A). These data demonstrate that the development of polycythemia and increased erythroid progenitors in OSX-VHL mutants is EPO dependent.

The kidney is the primary site for EPO production in adult animals, however the liver and brain can also produce levels of EPO sufficient to induce polycythemia under stress conditions (Haase, 2010). To confirm that Osterix-cre is not expressed in tissues other than bone that may affect erythropoiesis or produce EPO, we analyzed the efficiency of VHL recombination in OSX-VHL kidney, liver, brain, and spleen. While the recombined VHL allele (1-lox) was readily detectable in the bone, the recombined allele was not detected in the liver, kidney, or spleen of OSX-VHL mice (Figure S2B). Interestingly, a weak signal for the recombined VHL allele was detected in the brain suggesting that HIF signaling in brain could contribute to regulation of erythropoiesis in OSX-Cre mice (Figure S2B).

We next directly compared EPO mRNA expression in the kidney, liver, brain, and bone of OSX-VHL and OSX-Control mice. EPO levels in the kidney were suppressed in OSX-VHL mice ruling out the possibility that VHL deletion in the bone indirectly augments renal EPO (Figure 4C). EPO mRNA was not detected in the livers of OSX-VHL or OSX-Control mice, indicating that re-activation of hepatic EPO does not occur in OSX-VHL mutant mice (Figure 4C). Similarly, EPO levels in the brain were not induced in OSX-VHL mutant mice (Figure 4C). Unexpectedly, EPO was highly expressed in OSX-VHL bone. While EPO was not expressed at readily detectable levels in 8-week-old OSX-Control bone, EPO was expressed in OSX-VHL bone at levels significantly greater (6-fold) than those found in control kidneys (Figure 4C).

Because total bone preparations from OSX-VHL mice contain many cell types including VHL deficient osteoblasts and chondrocytes, we directly assessed whether osteoblasts and/or chondrocytes from OSX-VHL mice produce EPO. Primary bone marrow stromal cells from postnatal day 3 OSX-VHL hindlimbs expressed EPO at significantly higher levels compared to stromal cells isolated from OSX-CNTRL bone marrow (Figure 4D). In contrast, chondrocytes isolated from OSX-VHL growth plates did not express higher levels of EPO in comparison to controls (data not shown). These data suggest that VHL deficient osteoblasts express EPO at levels capable at elevating serum EPO and stimulating erythropoiesis.

Loss of HIF-2 in osteoblasts impairs EPO expression and numbers of erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow but does not cause anemia

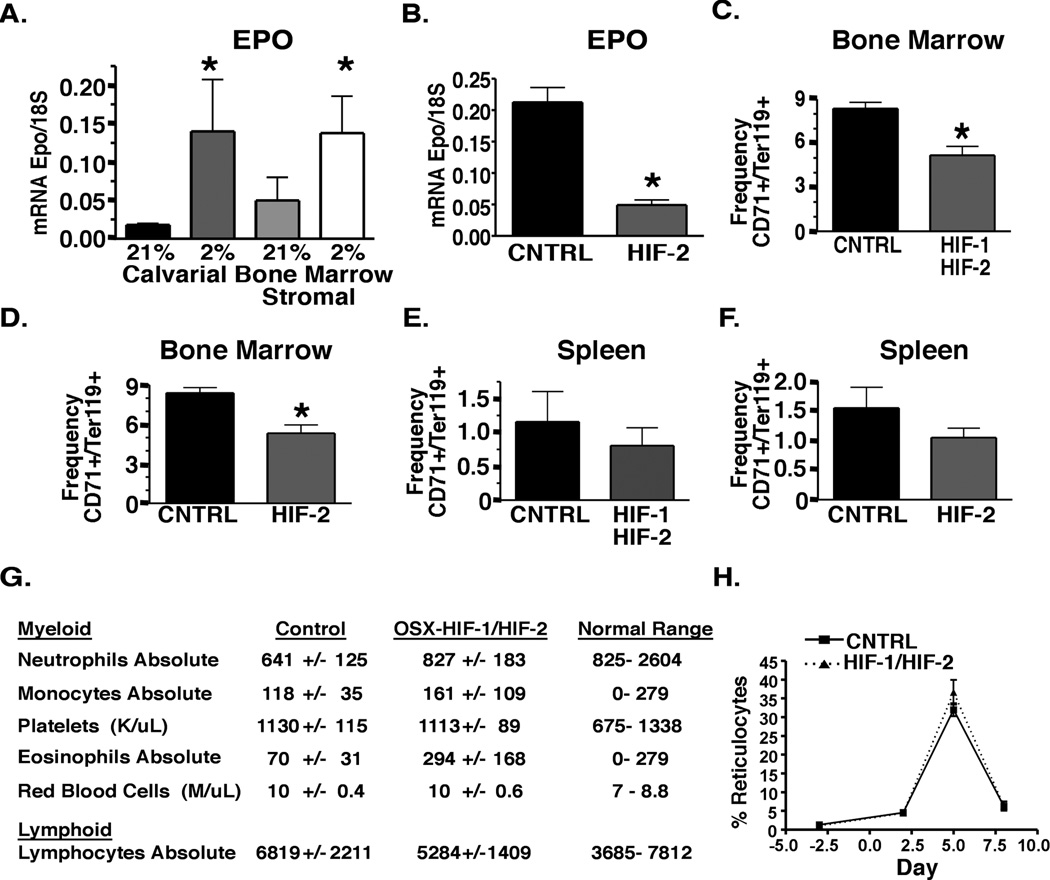

To determine whether wild-type osteoblasts express EPO in a HIF dependent manner, we exposed primary calvarial osteoblast and bone marrow stromal cell cultures from wild type mice to 21% oxygen (normoxia) and 2% oxygen (hypoxia) to induce HIF signaling in vitro. EPO expression in primary osteoblast cultures was significantly increased upon exposure to hypoxia (Figure 5A). Inactivation of HIF-2 in OSX-HIF-2 mice significantly reduced EPO expression in neonatal bone indicating that HIF-2 in osteoblasts drives EPO expression under physiologic conditions in vivo (Figure 5B). In adult bones, EPO expression was at the limit of detection in both OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-2 mice (data not shown).

Figure 5. HIF-1 and HIF-2 deletion in osteoblasts reduces EPO expression and erythroid progenitors in the bone but does not cause anemia.

A. Real time PCR analysis of EPO expression in primary osteoblast cultures isolated from calvarie or bone marrow exposed to 21% or 2% oxygen (n = 5 each group). B. Real time PCR analysis of EPO expression in neonatal hindlimbs (without growth plate) from OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-2 mice ( n = 4 each group). C–D Frequency of erythroid progenitors in 8-week-old OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 (C) and OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-2 (D) bone marrow (L, n = 4 each group). E–F. Frequency of erythroid progenitors in 8- week-old OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 (E) and OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-2 (F) spleen (L, n = 4 each group). G. CBC analysis of peripheral blood from 8-week-old OSX-Cre mutant mice. n = 8 in each group. H. OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mice have a normal response to erythropoietic stress. Mice (n = 5 in each group) were injected with phenylhydrazine on days 0 and 1. The proportion of reticulocytes in the red cell population was analyzed over 8 days. Corrected reticulocyte count (%) = reticulocyte count (%) X (hematocrit/45). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. See also Figure S3.

To determine whether HIF signaling in osteoblasts contributes to erythroid homeostasis, we analyzed the CD71+Ter119+ erythroid progenitor population in the bone marrow and spleen of OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 and OSX-HIF-2 mice. We observed a significant decrease in CD71+ Ter119+ cells in the bone marrow of OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 and OSX-HIF-2 mutants compared to littermate controls (Figure 5C–D). In contrast, erythroid progenitors were not significantly changed in spleen of OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 or OSX-HIF-2 mutants (Figure 5E–F). These data demonstrate that HIF signaling in osteoblasts has a physiological role in the regulation of erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow. Additionally, HIF-1/HIF-2 deletion in OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mice resulted in a significant decrease in trabecular bone volume accompanied by a reduced trend in hematopoieic progenitors in the bone marrow indicating that HIF signaling in osteoblasts regulates bone and hematologic homeostasis under physiologic conditions (Figure S3A–E).

Despite reduced erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow of OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mice, adult mutants exhibited normal hematocrit and red blood cell numbers in peripheral blood (Figure 5G). This result may be explained by the low rate of erythropoiesis required to maintain hematocrit under homeostatic conditions in adult mice. Therefore, we tested whether HIF signaling in osteoprogenitors affects stress erythropoiesis using the phenylhydarzine (PHZ) model of hemolytic anemia. OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mice were injected with PHZ on days 0 and 1. Since the proportion of reticulocytes in the red cell population allows for assessment of the erythropoietic rate (Socolovsky et al., 2001), reticulocytes were analyzed at days 2, 5, and 8 following PHZ injection. After PHZ treatment, reticulocytes dramatically increased reaching a maximum at day 5 (Figure 5H). Reticulocyte counts were not significantly different between OSX-CNTRL and OSX-HIF-1/HIF-2 mutants (Figure 5H). These data suggest that HIF signaling in osteoblasts contributes to the maintenance of erythroid progenitor homeostasis in the bone marrow, but is not necessary to ensure normal hematocrit in either homeostatic or stress conditions.

Modulation of the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway in osteoblasts is sufficient to induce EPO and protect from anemia

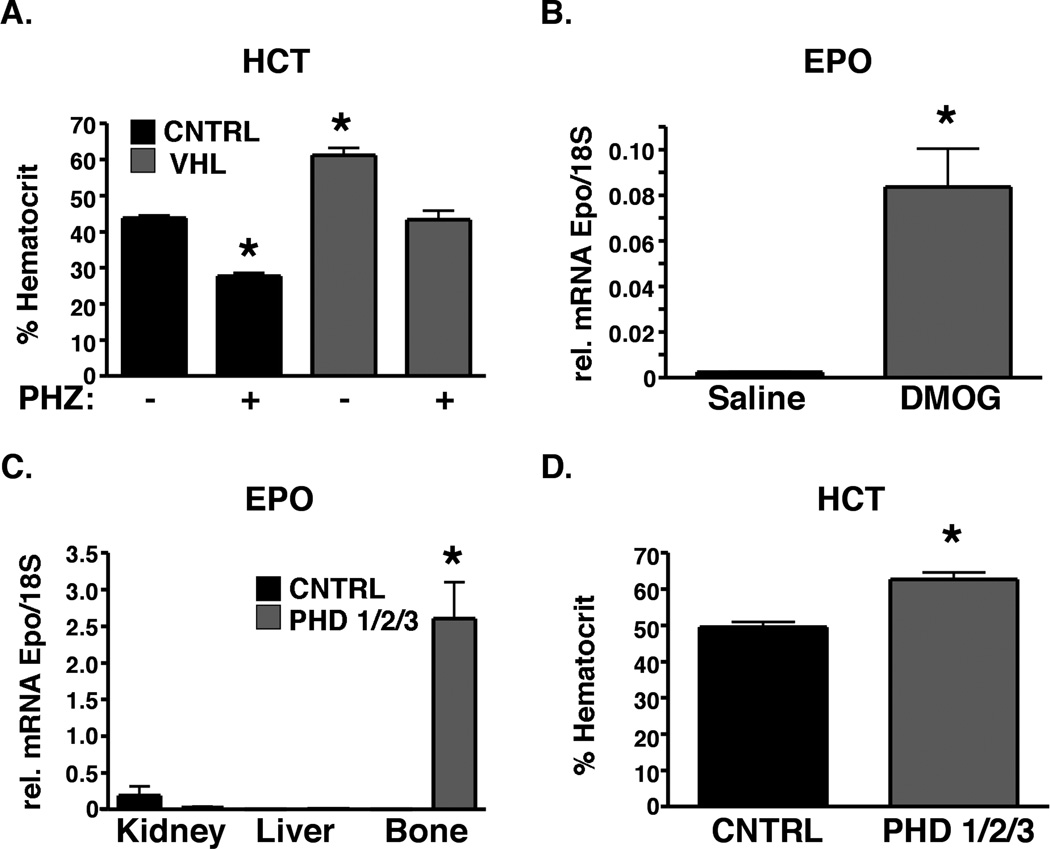

The findings above identify a role for HIF signaling in osteoblasts in the regulation of EPO and erythroid progenitors, raising the intriguing possibility that manipulation of the HIF pathway in osteoblasts could be a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of anemia. Therefore, we tested whether OSX-VHL mutant mice with increased serum EPO could be protected from stress-induced anemia. In the phenylhydrazine (PHZ) model of hemolytic anemia, OSX-Control mice developed an average hematocrit of 28% within 48 hours of initial PHZ injection (Figure 6A). In contrast, PHZ treated OSX-VHL mice exhibited average hematocrit values of 43% which were comparable to untreated control mice (Figure 6A). These data provide genetic evidence to suggest that manipulation of HIF activity in osteoblasts is a therapeutic strategy for anemia.

Figure 6. Modulation of the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway is sufficient to induce EPO production in adult bone and protect mice from anemia.

A. Augmented HIF signaling in osteoblasts protects mice from anemia. Percent hematocrit in 8-week-old OSX-Cre mice 48 hours after initial phenylhydrazine (PHZ) treatment ( n = 5 in each group). * indicate a statically difference compared to untreated OSX-Control mice as determined by Students t test (p<0.05). B. Pharmacologic inhibition of PHDs induces EPO expression in adult bone. EPO mRNA expression in 8-week-old bone 7 hours following intra-femoral injection of saline or DMOG ( n = 3 in saline and n = 3 in DMOG groups). C. Genetic inhibition of PHD1/2/3 activates Epo expression in bone. EPO mRNA expression in 8 week old OSX-Cre mutant mice ( n = 5 per group). D. Prolyl hydroxylase inhibition in osteoblasts increases hematocrit in 8-weekold mice ( n = 5 per group). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

The prolyl hydroxylase enzymes PHD1, 2, and 3 (PHD1,2,3) cooperate with VHL to target HIF-1 and HIF-2 for proteasomal degradation. PHDs belong to a super family of 2 oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that require Fe2+, ascorbate, and 2-oxoglutarate for enzymatic activity (Kaelin and Ratcliffe, 2008). Several different classes of PHD inhibitors (PHI) have shown efficacy in pre-clinical models of anemia and are in clinical trials for the treatment of anemia (Hsieh et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2010). To determine whether PHI inhibition is sufficient to activate EPO expression in bone, we treated adult mice with the PHI, DMOG. Local injection of DMOG in bone resulted in a significant increase in EPO expression in bone (Figure 6B). To determine whether PHD inhibition specifically in osteoblasts drives EPO expression, we generated mice lacking PHD1,2,3 in osteoblasts using Osterix-Cre mediated recombination of the PHD1,2,3 floxed alleles (Takeda et al., 2008). PHD1,2,3 deletion in osteoblasts dramatically increased EPO in bone and hematocrit values (Figure 6C–D). The induction of EPO expression in bone and hematocrit in OSX-PHD1/2/3 mice was comparable to that observed in OSX-VHL mice, demonstrating that PHD inhibition in bone phenocopies VHL deletion in bone. Collectively, these results show that manipulation of the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway in osteoblasts is sufficient to induce EPO in bone, elevate hematocrit, and protect mice from stress-induced anemia. These findings provide pre-clinical evidence to indicate that targeting the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway in the osteoblastic niche is a therapeutic strategy to elevate EPO in the local hematopoietic microenvironment. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the mechanism of action for PHI-mediated EPO production in vivo may include EPO production by osteoblasts.

Discussion

In order to maintain erythroid homeostasis, EPO expression is tightly regulated by developmental, physiological, and cell-type specific factors. During development, the source of EPO switches from the fetal liver to the kidney where hypoxia and HIF signaling are the primary stimulus for EPO production (Haase, 2010). In response to acute anemia or hypoxia, hepatocytes can re-activate EPO expression (Kapitsinou et al., 2010). In most other cell types, EPO expression is strongly repressed by mechanisms that involve the GATA family of transcriptional repressors (Obara et al., 2008). Notably, VHL has been inactivated in over 13 distinct cell types in vivo and of these cell types, only 3 have been reported to induce erythrocytosis including glial cells, hepatocytes, and renal interstitial cells (Kapitsinou and Haase, 2008). While the kidney and liver are the major producers of EPO, EPO expression has also been reported in the brain, lung, heart, spleen and reproductive tract (Haase, 2010). Of these tissues, the brain is the only other tissue shown to have the capacity to produce EPO that functionally regulates erythropoiesis (Weidemann et al., 2009). Local EPO production is thought to have a tissue protective effect by inducing anti-apoptotic effects, proliferation, differentiation, and survival (Haase, 2010). Our findings reveal an unexpected source of EPO within the hematopoietic microenvironment capable of stimulating erythropoiesis. While the kidney remains the primary organ controlling hypoxia-driven EPO and erythropoiesis, we demonstrate that activation of the HIF pathway in osteoblasts protects mice from stress-induced anemia. Here we identified an unexpected role for the PHD/VHL/HIF signaling pathway in osteoblasts in the production of EPO and modulation of erythropoiesis.

HIF overexpression in mature osteoblasts leads to aberrant bone vascularization associated with augmented VEGF expression raising the possibility that enhanced VEGF may contribute to some of the phenotypes observed in OSX-VHL mutants (Wang et al., 2007). Constitutive VEGF expression in osteo-chondroprogenitors leads to increased bone mass, aberrant vascularization and enhanced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors from the bone marrow. However, the number of circulating red or white blood cells were not changed in these animals (Maes et al., 2010a). While we cannot exclude the possibility that augmented VEGF production may contribute to bone accumulation and HSC expansion in OSX-VHL mutants, we demonstrate that the development of polycythemia is EPO dependent.

Consistent with previous findings, activation of the HIF pathway led to a dramatic increase of trabecular bone (Wang et al., 2007). In this study, we report that this increase in trabecular bone is associated with an expansion of functional HSCs. Our findings further highlight the important cross-talk between bone and the hematopoietic compartment, and underline a novel role of the HIF signaling pathway as component of this cross-talk. Interestingly, lack of HIF signaling in osteoblasts did not significantly affect HSC number in homeostatic conditions, though it altered the bone compartment, suggesting that the relationship between bone and hematopoiesis is complex and only partially elucidated.

These findings have important clinical implications for the treatment of anemia. Over 3 million patients suffer from anemia as a result of renal insufficiency. Recombinant EPO and derivatives are the standard therapy for the treatment of anemia. Despite its clinical effectiveness, recombinant EPO therapy is expensive, requires parenteral administration, and has the risk of producing an antigenic response. For these reasons, efforts are focused on developing cheaper, nonantigenic, and more easily administered agents for the treatment of anemia. Small molecule PHD inhibitors that pharmacologically activate the HIF signaling pathway are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of anemia. It is thought these small molecule therapies will revolutionize the treatment of anemia bringing both convenience and lower costs to millions of anemic patients (Yan et al., 2010). However, the mechanism of action for these inhibitors is not completely understood. It has been hypothesized that in patients with renal failure, the liver is the primary organ producing EPO (Kapitsinou et al., 2010; Minamishima and Kaelin, 2010). Our data indicate that in addition to the liver, osteoblasts can also produce EPO and increase red blood cell production following PHD inhibition. These findings are of particular importance because we discovered that local production of EPO by osteoblasts in the bone marrow microenvironment is sufficient to drive erythropoiesis. Our pharmacological approach unequivocally shows that EPO production can be significantly upregulated in osteoblasts of adult wild type mice. Furthermore, augmented HIF activity in osteoblasts also drives expansion of functional HSCs, which may provide additional therapeutic benefits for anemic patients.

Experimental Procedures

Generation and Analysis of Mice

Generation of and genotyping analysis of the VHL, HIF-1, HIF-2, PHD1/2/3 conditional mice and Osterix-Cre transgenic mice have been previously described (Gruber et al., 2007; Haase et al., 2001; Rodda and McMahon, 2006; Ryan et al., 1998; Takeda et al., 2006). With the exception of bone marrow transplantation studies, mice were generated in mixed C57/B6 and FVB/N genetic backgrounds. Therefore, for all studies littermate Cre-recombinase positive heterozygous floxed mice and Cre-negative homozygous floxed mice were used as controls. We found that the Osterix-Cre transgene did not affect any of the phenotypes described in this manuscript. All procedures involving mice were performed in accordance with the NIH guidelines for use and care of live animals and were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

PHI Inhibition in Bone Using DMOG

1.75mg of DMOG prepared in sterile saline and was injected directly into the femur using standard procedures (Zhan and Zhao, 2008). Seven hours following injection, mice were sacrificed and femurs were collected for RNA.

PHZ Stress Anemia Model

Mice were injected with 40mg/kg of PHZ in normal saline 2 times at 24-hour intervals. Forty-eight hours after the initial injection, mice were bled to obtain CBC analysis and reticulocyte counts.

DNA and RNA Isolation

DNA was isolated according to Laird et al. and used for genomic PCR (Laird et al., 1991). RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Immunohistochemistry, Histological, Histomorphometric Analysis

Hindlimbs from 8-week-old mice were dissected, fixed, decalcified and processed using standard procedures. HIF-1 was detected using the rabbit anti-human/mouse HIF-1 polyclonal antibody (RD systems AB1536) at a 1:500 dilution. HIF-2 was detected using the rabbit anti-human/mouse HIF-2 polyclonal antibody (Novus NB100-122) at a dilution of 1:100. CD31 was detected using CD31 (BD 550274) at a dilution of 1:200. All antibodies were incubated overnight at 4C, and developed using the TSA Biotin system (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

H&E staining was performed using standard methods. Histomorphometric analysis of tibias was performed using the Osteomeasure system (Osteometrics Inc.) as previously described (Ohishi et al., 2009).

B-galactosidase Staining

B-galactosidase staining was performed as previously described (Provot et al., 2007).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

FACS analysis was performed on total bone marrow and spleen cells. For analysis of the erythroid lineage, 1X106 cells were incubated with FITC anti-mouse CD71 (ebioscience) and biotin anti-mouse Ter119 (ebioscience). For hematopoietic progenitors and HSCs, 4X106 cells were incubated with biotinylated lineage antibodies (Ter119, B220, CD3, CD11b, Ly-6G; ebiosience), FITC anti-mouse c-Kit (ebioscience), PE anti-mouse Sca-1, APC anti-mouse CD150 (TC15-12F12.2, Biolegend), Alexa Flour 700 anti-mouse CD48 (HM48-1, Biolegend), and eFlour 450 CD16/CD32 (93, ebioscience).

Antibodies were incubated with cells for 30 minutes (erythroid lineage) or 60 minutes (HSC/progenitors) in PBS containing 2% BSA on ice. Cells were washed 3 times and incubated with Streptavidin-PE-Cy7 (ebioscience) for 30 minutes. Samples were washed and data was collected on a LSRII (BD Bioscience). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar). FACS experiments shown are a representative experiment in which littermate controls were directly compared to OSX-mutant mice. All experiments were independently performed at least three times.

Real Time PCR

Real time PCR was performed as previously described (Rankin et al., 2007). For 18S amplification, cDNA was diluted 1:50. The primers used to amplify specific target genes can be found in Supplemental Procedures.

Generation and Production of Adenovirus

The production and purification of the EPO-receptor IgG2a-Fc adenoviruses were performed as previously described (Tam et al., 2006). 6.5-week-old OSX-VHL or OSX-CNTRL mice were bled for a baseline hematocrit at day -1. At day 0, mice were injected with 1X108 p.f.u. of the indicated adenovirus through the tail vein. Mice were bled once per week for 23 days following injection.

CBC Analysis

CBC analysis was performed by the Department of Comparative Medicine at Stanford University using an Abbott Cell-Dyn 3500 and by analysis of prepared blood smears using a Wrights-Giemsa stain.

ELISA

VEGF and EPO ELISAs were performed according to manufacturer instructions with the exception that serum was incubated in the ELISA plate overnight at 4C (RandD Systems).

Primary Bone Marrow Stromal and Calvarial Osteoblast Isolation

Bone marrow stromal cells and calvarial osteoblasts from postnatal day 3 hindlimbs were isolated by serial collagenase digestion as previously described (Wu et al., 2008). Fractions 3–6 were plated in alphaMEM 10% FBS and incubated under 21% or 2% oxygen for 4 days to reach confluency.

BFU-E and CFU-E Assays

Bone marrow mononuclear and spleen cells were isolated and resuspended in Iscove’s MDM 2% FBS. BFU-E and CFU-E assays were performed using methocult M03434 and M03334 respectively in triplicate according to manufacturer’s instructions (Stem Cell Technologies).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (GraphPad). In all cases a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test was performed to analyze statistical differences between groups. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

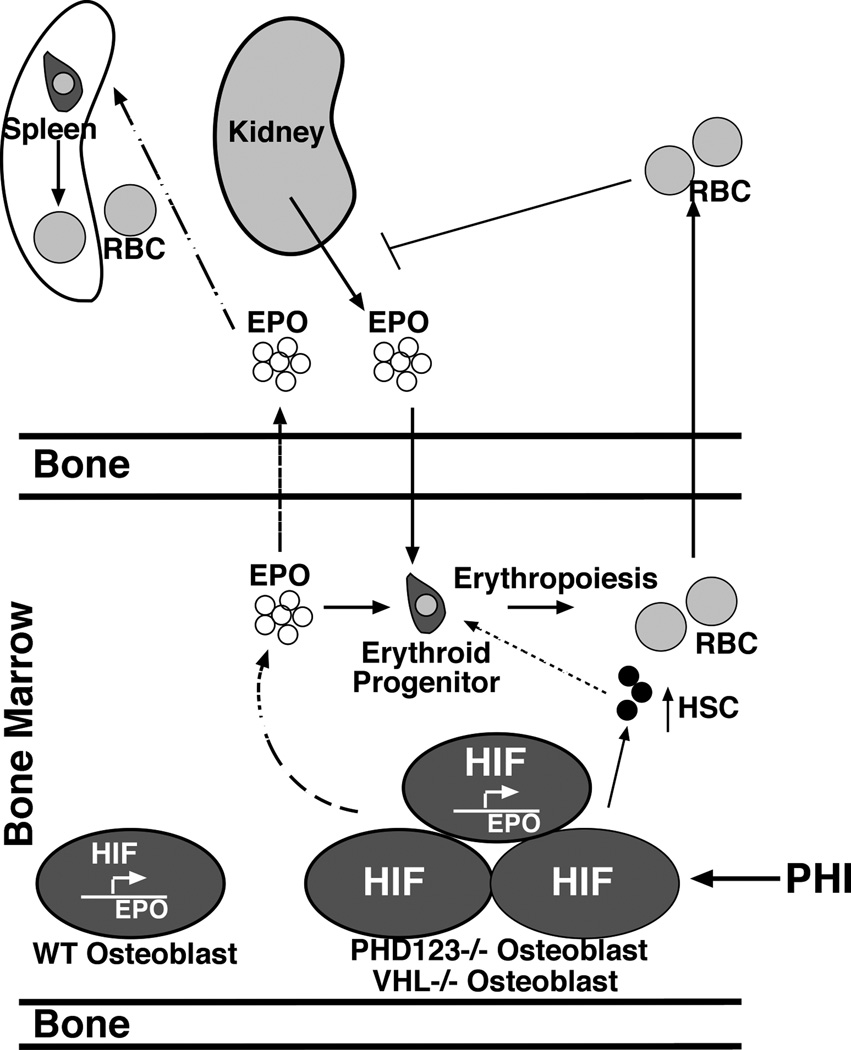

Figure 7. The HIF signaling pathway in osteoblasts directly modulates erythropoiesis through the production of EPO and the number of HSCs.

Osteoblasts produce EPO through a HIF dependent mechanism under physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions. Osteoblasts express HIF-1 and HIF-2 that transcriptionally activate EPO expression. In conditions of augmented HIF signaling (dashed line), osteoblasts produce both local and systemic levels of EPO that stimulate erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and spleen. Constitutive hyperactivation of HIF signaling leads to increased red blood cells (RBC) and oxygen in the blood that feeds back to suppress renal EPO production. Augmented HIF signaling in osteoblasts through VHL or PHD1/2/3 inhibition is sufficient to drive EPO expression in adult bone, elevate hematocrit, and protect mice from stress-induced anemia. Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of PHDs using prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (PHI) is sufficient to activate EPO in adult bone. Additionally, augmented HIF activity in osteoblasts expands HSCs indicating that therapeutic manipulation of the PHD/VHL/HIF pathway in osteoblasts is a therapeutic strategy to elevate both EPO and HSCs in the local hematopoietic microenvironment.

Research Highlights.

Osteoblasts produce EPO through a HIF dependent mechanism.

Modulation of PHD/VHL/HIF signaling in osteoblasts induces EPO and protects from anemia.

Augmented HIF activity in osteoblasts expands the HSC niche in the bone marrow.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants CA67166 and CA116685, and the Sydney Frank Foundation (A.J.G.) and NIH AR048191–06 (A.J.G. and E.S.). E.B.R. is supported by the NIH National Research Service Award T32 CA09151 from the National Cancer Institute. C.W. is supported by is supported by an Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship. The authors would like to thank all of the investigators that generated and made the floxed/transgenic mice available for these studies: Dr. Volker Haase (VHL floxed), Dr. Randall Johnson (HIF-1 floxed), Drs. Brian Keith and Celeste Simon (HIF-2 floxed), Dr. Guo-Hua Fong (PHD1,2,3 floxed), and Dr. Andrew McMahon (Osterix-Cre).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams GB, Martin RP, Alley IR, Chabner KT, Cohen KS, Calvi LM, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nbt1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akeno N, Robins J, Zhang M, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Clemens TL. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor by IGF-I in osteoblast-like cells is mediated by the PI3K signaling pathway through the hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha. Endocrinology. 2002;143:420–425. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flygare J, Rayon Estrada V, Shin C, Gupta S, Lodish HF. HIF1alpha synergizes with glucocorticoids to promote BFU-E progenitor self-renewal. Blood. 2011;117:3435–3444. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber M, Hu CJ, Johnson RS, Brown EJ, Keith B, Simon MC. Acute postnatal ablation of Hif-2alpha results in anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2301–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608382104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase VH. Hypoxic regulation of erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F1–F13. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00174.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase VH, Glickman JN, Socolovsky M, Jaenisch R. Vascular tumors in livers with targeted inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1583–1588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh MM, Linde NS, Wynter A, Metzger M, Wong C, Langsetmo I, Lin A, Smith R, Rodgers GP, Donahue RE, et al. HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibition results in endogenous erythropoietin induction, erythrocytosis, and modest fetal hemoglobin expression in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2007;110:2140–2147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr., Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitsinou PP, Haase VH. The VHL tumor suppressor and HIF: insights from genetic studies in mice. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:650–659. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitsinou PP, Liu Q, Unger TL, Rha J, Davidoff O, Keith B, Epstein JA, Moores SL, Erickson-Miller CL, Haase VH. Hepatic HIF-2 regulates erythropoietic responses to hypoxia in renal anemia. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird PW, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Goossens S, Bartunkova S, Drogat B, Coenegrachts L, Stockmans I, Moermans K, Nyabi O, Haigh K, Naessens M, et al. Increased skeletal VEGF enhances beta-catenin activity and results in excessively ossified bones. EMBO J. 2010a;29:424–441. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Kobayashi T, Selig MK, Torrekens S, Roth SI, Mackem S, Carmeliet G, Kronenberg HM. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell. 2010b;19:329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma'ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamishima YA, Kaelin WG., Jr. Reactivation of hepatic EPO synthesis in mice after PHD loss. Science. 2010;329:407. doi: 10.1126/science.1192811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JK, Balan C, Allgeier AM, Kasparian A, Viswanadhan V, Wilde C, Allen JR, Yoder SC, Biddlecome G, Hungate RW, et al. Dipeptidyl-quinolone derivatives inhibit hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha prolyl hydroxylases-1, -2, and -3 with altered selectivity. J Comb Chem. 2010;12:676–686. doi: 10.1021/cc100073a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara N, Suzuki N, Kim K, Nagasawa T, Imagawa S, Yamamoto M. Repression via the GATA box is essential for tissue-specific erythropoietin gene expression. Blood. 2008;111:5223–5232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi M, Chiusaroli R, Ominsky M, Asuncion F, Thomas C, Khatri R, Kostenuik P, Schipani E. Osteoprotegerin abrogated cortical porosity and bone marrow fibrosis in a mouse model of constitutive activation of the PTH/PTHrP receptor. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2160–2171. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk CJ, Rossi DJ, Mansson R, Attema JL, Norddahl GL, Chan CK, Sigvardsson M, Weissman IL, Bryder D. Elucidation of the phenotypic, functional, and molecular topography of a myeloerythroid progenitor cell hierarchy. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provot S, Zinyk D, Gunes Y, Kathri R, Le Q, Kronenberg HM, Johnson RS, Longaker MT, Giaccia AJ, Schipani E. Hif-1alpha regulates differentiation of limb bud mesenchyme and joint development. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:451–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Biju MP, Liu Q, Unger TL, Rha J, Johnson RS, Simon MC, Keith B, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1068–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI30117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133:3231–3244. doi: 10.1242/dev.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan HE, Lo J, Johnson RS. HIF-1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. Embo J. 1998;17:3005–3015. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. HIF-1, O(2), and the 3 PHDs: how animal cells signal hypoxia to the nucleus. Cell. 2001;107:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL, Wang GL. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5447–5454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek T, Kocabas F, Zheng J, Deberardinis RJ, Mahmoud AI, Olson EN, Schneider JW, Zhang CC, Sadek HA. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolovsky M, Nam H, Fleming MD, Haase VH, Brugnara C, Lodish HF. Ineffective erythropoiesis in Stat5a(−/−)5b(−/−) mice due to decreased survival of early erythroblasts. Blood. 2001;98:3261–3273. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Aguila HL, Parikh NS, Li X, Lamothe K, Duan LJ, Takeda H, Lee FS, Fong GH. Regulation of adult erythropoiesis by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Blood. 2008;111:3229–3235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-114561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Ho VC, Takeda H, Duan LJ, Nagy A, Fong GH. Placental but not heart defects are associated with elevated hypoxia-inducible factor alpha levels in mice lacking prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8336–8346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00425-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takubo K, Goda N, Yamada W, Iriuchishima H, Ikeda E, Kubota Y, Shima H, Johnson RS, Hirao A, Suematsu M, et al. Regulation of the HIF-1alpha level is essential for hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam BY, Wei K, Rudge JS, Hoffman J, Holash J, Park SK, Yuan J, Hefner C, Chartier C, Lee JS, et al. VEGF modulates erythropoiesis through regulation of adult hepatic erythropoietin synthesis. Nat Med. 2006;12:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visnjic D, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Katavic V, Lorenzo J, Aguila HL. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. 2004;103:3258–3264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wan C, Deng L, Liu X, Cao X, Gilbert SR, Bouxsein ML, Faugere MC, Guldberg RE, Gerstenfeld LC, et al. The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI31581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidemann A, Kerdiles YM, Knaup KX, Rafie CA, Boutin AT, Stockmann C, Takeda N, Scadeng M, Shih AY, Haase VH, et al. The glial cell response is an essential component of hypoxia-induced erythropoiesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3373–3383. doi: 10.1172/JCI39378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Liu X, Jaenisch R, Lodish HF. Generation of committed erythroid BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors does not require erythropoietin or the erythropoietin receptor. Cell. 1995;83:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Purton LE, Rodda SJ, Chen M, Weinstein LS, McMahon AP, Scadden DT, Kronenberg HM. Osteoblastic regulation of B lymphopoiesis is mediated by Gs{alpha}-dependent signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16976–16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802898105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Colandrea VJ, Hale JJ. Prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing protein inhibitors as stabilizers of hypoxia-inducible factor: small molecule-based therapeutics for anemia. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2010;20:1219–1245. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2010.510836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D, Pastore YD, Divoky V, Liu E, Mlodnicka AE, Rainey K, Ponka P, Semenza GL, Schumacher A, Prchal JT. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 deficiency results in dysregulated erythropoiesis signaling and iron homeostasis in mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25703–25711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AY, Shimoda LA, Iyer NV, Huso DL, Sun X, McWilliams R, Beaty T, Sham JS, Wiener CM, Sylvester JT, et al. Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:691–696. doi: 10.1172/JCI5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Zhao Y. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant in mice by intra-femoral injection. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;430:161–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-182-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, Huang H, He X, Tong WG, Ross J, Haug J, Johnson T, Feng JQ, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.