Abstract

Objective

To describe a case of intentional ingestion of hand sanitizer in our hospital and to review published cases and those reported to the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS).

Design

A case report, a literature review of published cases, and a query of the National Poison Data System (NPDS).

Measurements

Incidence and outcome of reported cases of unintentional and intentional ethanol containing-hand sanitizer ingestion in the United States from 2005 through 2009.

Main Results

A literature search found 14 detailed case-reports of intentional alcohol-based hand sanitizer ingestions with one death. From 2005 to 2009, NPDS received reports of 68,712 exposures to 96 ethanol-based hand sanitizers. The number of new cases increased by an average of 1894 (95% CI: 1266, 2521) cases per year (p = 0.002). In 2005, the rate of exposures, per year, per million U.S residents was 33.7 (95% CI: 28.4, 39.1); from 2005 to 2009, this rate increased on average by 5.87 per year (95%CI: 3.70, 8.04; p=0.003). In 2005, the rate of intentional exposures, per year, per million U.S residents, was 0.68 (95%CI: 0.17-1.20); from 2005 to 2009, this rate increased on average by 0.32 per year (95%CI: 0.11,0.53; p=0.02).

Conclusions

The number of new cases per year of intentional hand sanitizer ingestion significantly increased during this five - year period. While the majority of cases of hand sanitizer ingestion have a favorable outcome, 288 moderate and 12 major medical complications were reported in this NPDS cohort. Increased awareness of the risks associated with intentional ingestion is warranted, particularly among healthcare providers caring for persons with a history of substance abuse, risk-taking behavior or suicidal ideation.

Keywords: ethanol hand sanitizer, alcohol poisoning, hand sanitizer ingestion

Introduction

Alcohol-based sanitizers are routine instruments of hand hygiene in health care facilities and promote greater adherence to hand washing (1). Several reports describe the ingestion of hand sanitizers as a surrogate for potable alcohol by patients with a history of mental illness or substance abuse. We describe a life–threatening intentional ingestion of an ethanol-based hand sanitizer in an immunocompromised patient. The case is reviewed in the context of published case reports and an analysis of five years of reports to the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) for exposures to ethanol-containing hand sanitizers.

Case Report

A 17 yr old, 37 kg male with severe combined immunodeficiency was hospitalized for pneumonia and treated with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. The patient had given consent and was enrolled in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols for the treatment of his underlying disorder (NCT 00128973 and 00426517). The case description below is not related to the treatment of his immunodeficiency as per the IRB approved studies (NCT 00128973 and 00426517) but rather was an intentional ingestion resulting in alcohol poisoning. This event was not part of an IRB study and one where consent would not be relevant. He had a history of recurrent sino-pulmonary infections, inflammatory bowel disease and required a gastrostomy tube for nutritional support. His multiple prolonged hospitalizations had resulted in anxiety and depressed mood and he was treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and anxiolytics. Despite his chronic illness, he was graduating from high school and entering college.

Early in the morning of the sixth hospital day, he complained of dizziness to his nurse. His pulse was 133 beats/min, blood pressure 160/88 mmHg, and oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. A finger stick blood sugar was 135mg/dL. Upon arrival of the rapid response team, he was somnolent but moved all extremities, opened his eyes spontaneously and obeyed simple commands. His pupils were 5- 6 mm and sluggish in response to light. After transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) his left pupil became dilated and fixed, spontaneous movement ceased and he was emergently intubated. His subsequent pupillary responses to light fluctuated. Supportive measures were instituted.

On admission to the ICU, laboratory results revealed: sodium 147mmol/L, potassium 3.4mmol/L, chloride 111mmol/L, bicarbonate 27mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 8mg/dl, creatinine 0.64 mg/dl, and glucose 128mg/dl. Calculated osmolality was 304 mOsm/kg and measured osmolality was 388 mOsm/kg. Urine ketones were negative. Complete blood count revealed total leukocytes of 14.1× 103/uL, hemoglobin 11.6g/dL, hematocrit 37%, and platelet count 463×103/uL. Computerized axial tomography of the head showed normal brain parenchyma with no mass effect or midline shift. After admission to the ICU, a nurse from the patient’s floor found an empty 500 mL bottle of Avagard D Instant Hand Antiseptic with Moisturizers® (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN) hand sanitizer in the patient’s wastebasket, covered with a towel. It contains 61% w/w ethyl alcohol with the following excipients: beheneth-10, behenyl alcohol, C20-40 pareth-24, cetyl palmitate, diisopropyl dimer dilinoleate, dimethicone, glycerin, polyethylene glycol, squalane, and water. A urine toxicology screen was positive for ethanol.

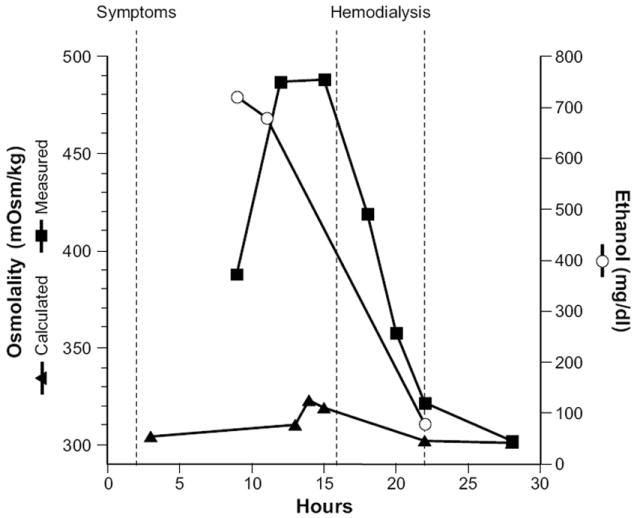

A serum ethanol level drawn more than six hours after the reported onset of symptoms was 720 mg/dL and because of his comatose state and rising serum osmolality, the patient underwent hemodialysis (Figure 1). Within 3 hrs he awoke and followed simple commands. The following morning he was extubated and was alert and cooperative. He admitted to infusing the hand sanitizer into his gastrostomy tube because he wanted to “get a buzz” but denied any suicidal intent. Notably, he admitted to several ingestions during the past year of other ethanol-based hand sanitizers, mouthwash and alcoholic beverages through his gastrostomy tube.

Figure 1.

Time course of events associated with ingestion of ethanol-based (61%) hand sanitizer. Changes in calculated (▲) and measured (■) serum osmolality (mOsm/kg) are shown with the accompanying serum ethanol levels (mg/dl) (○). Symptoms were estimated to have begun within 1 hour of ingestion and hemodialysis was started after the peak osmolality was measured.

Methods

A literature search was performed using PubMed, Scopus and Embase with cross-referencing to relevant articles. The following search terms were used: Hand sanitizer(s), alcohol based hand rub(s), ethanol based hand rub(s), alcohol based hand gel(s), ethanol based hand gel(s), alcohol hand rub(s), ethanol hand rub(s), alcohol hand gel(s), or ethanol hand gel(s) and ingestion or poisoning. Additionally, a query of the NPDS was conducted to identify exposures to 96 different ethanol-containing hand sanitizer products reported to United States Poison Centers between 2005 and 2009. The NPDS data collection process, field definitions, and participating poison centers have been previously described (2). The exposures were classified by age (< 6 yr, 6 – 19 yr, and ≥ 20 yrs), intentional or unintentional exposure, and six possible medical outcomes (not followed and judged as non-toxic or minimal clinical effects possible; no effect; minor; moderate; major; and death). When specific ages were unavailable, categorized ages (i.e. child < 5, teenager, adult, etc) were replaced with the estimated average ages within each group (2.4% of total data). The average rates of change for the number and rate of exposure were estimated using linear regression. Adjustment for the U.S. population increases during this 5 year period (http://www.census.gov/popest/national/NA-EST2009-01.html) were made using the population estimate on July 1 of each year. Additional analyses considered the ethanol-containing hand sanitizer exposures relative to the total number of human exposure calls per year to NPDS during this 5 year period and were conducted using a similar approach.

Results

Fourteen published case reports were identified describing intentional ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizers containing either ethanol, isopropanol or mixtures of isopropanol, 1-propanol, 2-propanol and/or acetone (3-16) (Table 1). The median age was 44.5 yrs (range: 27-81 yrs) with 9 men and 4 women (1 gender not specified). Most were described as having mental illness, substance or alcohol abuse, with the majority of ingestions occurring in the emergency department or after admission to the hospital. Four admitted to a suicide attempt. Thirteen of the 14 patients recovered and 1 death was reported.

Table 1.

Case reports of intentional alcohol-based hand sanitizer ingestions

| Case | Ref | Age (yrs) and sex | Psychiatric Illness | Hospital Admission Diagnosis | Stated Ingestion Intent | Location of Ingestion (Number of acute attempts) | Hand Sanitizer Alcohol Concentration | Blood Concentration of Alcohols (mg/dl) | Therapeutic Interventions | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (3) | 49 M | Alcoholism | Alcohol intoxication | NS | Hospital | 85% ethanol | Ethanol 335 | Gastric lavage, intubation | Recovery |

| 2 | (4) | 38 M | Alcoholism | Suspected intoxication | NS | Hospital | Not specified | Ethanol > 500 | Intubation | Recovery |

| 3 | (5) | 38 F | Chronic psychosis | Pancreatic duct stone | Suicide attempt | Hospital | 51% isopropanol, 34% propanol-1 | isopropanol 37, acetone 227, propanol-1 < 10 | Fomepizole | Recovery |

| 4 | (6) | 27 M | Polysubstance abuse, depression | Pancreatitis | Suicide attempt | ED (2 episodes within 2 months) | 63% isopropanol | Elevated isopropanol levels | Intubation | Recovery |

| 5 | (7) | NS F | Alcoholism | Alcohol withdrawal | Intoxication | Hospital | 65 – 75% ethanol | Ethanol 700 | Intubation | Recovery |

| 6 | (8) | 81 F | NS | Cardiac rehabilitation | Suicide attempt | Cardiac Rehab | 85% ethanol | Ethanol 228 | Supportive Care | Recovery |

| 7 | (9) | 43 M | Alcoholism | Chest pain | Intoxication | Hospital | 63% isopropanol | Isopropanol 13.6, acetone 269 | Supportive care Vasopressors | Recovery |

| 8 | (10) | 49 M | NS | Acute intoxication | NS | Correctional Facility | 62% ethanol | Ethanol 335 | Fluid repletion | Recovery |

| 9 | (11) | 37 M | NS | Hospital Visitor | NS | Hospital | 27.6% 1-propanol, 36.1% 2-propanol | NS | Gastic lavage, activated charcoal, intubation | Recovery |

| 10 | (12) | 53 M | Alcoholism | Acute intoxication | Intoxication | Outpatient and hospital | Isopropanol with 1st ingestion episode and 2nd episode 61% ethanol | Isopropanol 100 acetone 207 both from 1st episode, ethanol 376, 2nd episode | Intensive care admission | Recovery |

| 11 | (13) | 46 M | Bipolar disorder, Alcoholism | Acute intoxication | Intoxication | Outpatient and in hospital | 62% ethanol | NS | Observation | Recovery |

| 12 | (14) | NS | Borderline Personality Syndrome | NS | NS | Correctional Facility | Isopropanol, | Isopropanol 195, acetone 128 | Intubation Hemodialysis | Recovery |

| 13 | (15) | 71 M | Alcoholism | Hyponatremia | NS | Hospital, 2 episodes | 70% alcohol 1st episode 48% 2-propanol and 32% 1-propanol, 2nd episode | 1st episode ethanol 180 2nd episode 1-propanol 850, 2-propanol 1600, acetone 55 | Intensive Care | Death |

| 14 | (16) | 33 F | Depression Alcoholism | Depression | Suicide Attempt | Psychiatric ward | 43% ethanol | Ethanol 414 | Intubation | Recovery |

M- male, F-female, NS-not specified, ED – emergency department

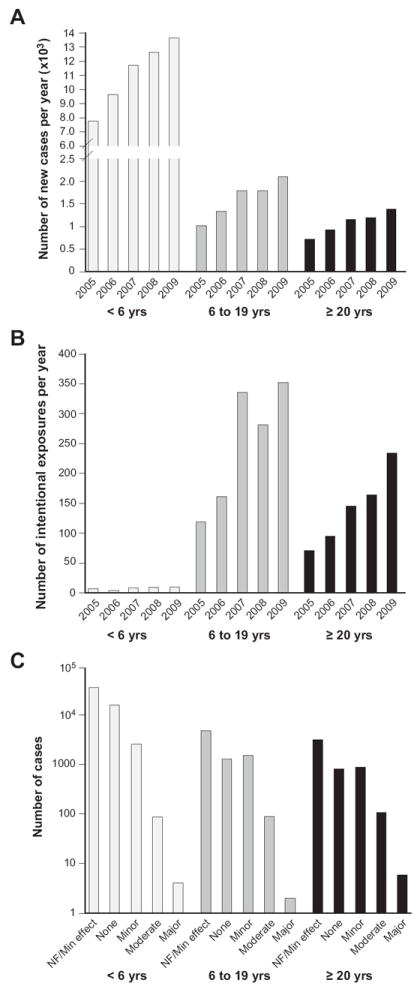

NPDS received reports of 68,712 hand sanitizer exposures between 2005 and 2009 (Figure 2A and B). 80.5% of the reports (55,323 exposures) occurred in children less than 6 years of age (median age: 2.00 yrs; interquartile range (IQR), which goes from the 25th to 75th percentiles: 1.25, 2.00 yrs), with equal proportion of exposures in males and females (51.5% vs. 48.5%) when adjusted for the gender ratio (1.05/1.00) in the US population (p = 0.08). In this age cohort, 99.9% of exposures were unintentional. In 6 to 19 year old persons (median age: 10yrs; IQR: 7, 13yrs), 8,020 exposures were reported with the majority as unintentional exposures (77%), 16.0% (1,283) as intentional exposures, and 7% where the intention of the exposure not specified. In this age cohort, more exposures occurred in males than females (59.6% vs. 40.4%, p <0.0001). In adults ≥ 20 yrs of age (median: 47 yrs; IQR: 32, 57 yrs, with a range of 20 to 101 yrs), 5,369 exposures were reported; 78.0% (4,188) were unintentional, 13.0% (698) were intentional exposures, and 9% where the intention of the exposure not specified. In this age cohort, more exposures occurred in females than males (62.0% vs. 38.0%, p <0.0001).

Figure 2.

A) The total number of exposures of ethanol-containing hand sanitizers increased from 2005 to 2009 by an average of 1894 (95% CI: 1266, 2521; p=0.002) cases per year. In 2005, the rate of exposures, per year, per million U.S residents, was 33.7 (95% CI: 28.4, 39.1); from 2005 to 2009, this rate increased on average by 5.87 per year (95%CI: 3.70, 8.04; p=0.003). The increase in new cases of exposures was significant in each age cohort; < 6 yrs: 1469 (95% CI: 1003, 1935; p=0.002)/yr, ages 6 -19 yrs: 265 (95%CI: 138, 391; p=0.007)/yr and age ≥ 20 yr 160 (95%CI: 100, 220; p=0.003).

B) In 2005, the rate of intentional exposures, per year, per million U.S residents, was 0.68 (95%CI: 0.17,1.20); from 2005 to 2009, this rate increased on average by 0.32 per year (95%CI: 0.11, 0.53; p=0.02). The increase in each age cohort was; ages 6 – 19 yrs by 58.5 (95% CI: 1.7, 115.3; p=0.05)/yr and in ages >20 yrs by 39.5 (95%CI: 25.7, 53.3; p=0.003).

C) Medical outcomes of exposure to ethanol-containing hand sanitizers were categorized by severity. 66% of the exposures were not followed but considered to be non-toxic or minimal clinical effects possible (NF/Min Effect). Medical outcomes in the three cohorts (< 6 yrs, 6 – 19 yrs and ≥ 20 yrs) were 15,883 (28.7% of the cohort), 1294 (16.1%) and 825 (15.4%) had no effect, 2567 (4.6%), 1518 (18.9%) and 890 (16.6%) had minor effects, 88 (0.2%), 91 (1.0%) and 109 (2.0%) had moderate effects and 4 (<0.1%), 2 (<0.1%) and 6 (0.1%) had major effects respectively. No deaths were reported.

The total number of exposures of ethanol-containing hand sanitizers increased from 2005 to 2009 by an average of 1894 (95% CI: 1266, 2521; p=0.002) cases per year. In 2005, the rate of exposures, per year, per million U.S residents, was 33.7 (95% CI: 28.4, 39.1); from 2005 to 2009, this rate increased on average by 5.87 per year (95%CI: 3.70, 8.04; p=0.003). This increase in cases was not simply a result of an increase in human exposure calls alone. When adjusted for increases in US population, the number of exposure calls did not change significantly during this five year time period (p=0.90). When indexed to the number of human exposure calls each year, the rate of ethanol-based hand sanitizers exposure calls (unintentional and intentional) increased during this period at a rate of 0.723/1000 exposure calls (95%CI: 0.491, 0.955;p=0.002). In 2005, the rate of intentional exposures, per year, per million U.S residents, was 0.68 (95%CI: 0.17-1.20); from 2005 to 2009, this rate increased on average by 0.32 per year (95%CI: 0.11, 0.53; p=0.02). When indexed to the number of human exposure calls each year, the rate of reported intentional exposure increased during this period at a rate of 0.039/1000 exposure calls (95% CI: 0.014, 0.064; p=0.02). The majority of cases of hand sanitizer ingestion had a favorable outcome but 288 moderate and 12 major medical complications were reported in this 5-year cohort (Figure 2C). There were no reported deaths.

Discussion

Acute ethanol intoxication can result in several serious, even life-threatening clinical effects. These include hypothermia, central nervous system and respiratory depression, cardiac dysrhythmias or arrest, hypotension, nausea and vomiting, acute liver injury, myoglobinuria, lactic and ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia (17). The immediate life-threatening events relate to the anesthetic effects of high doses of ethanol that produce hypoventilation and hypoxia that may result in anoxic brain injury. Ethanol toxicity can be lethal in the range of 400 mg/dL or greater, although death has occurred at lower levels (18). Therapy of severe ethanol overdose is primarily supportive by providing airway protection, respiratory support and addressing associated metabolic disturbances. Hemodialysis is effective at removing ethanol but is usually unnecessary if the airway is protected, there is no other severe organ injury present and the patient is responding to supportive measures for cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Alcohol dehydrogenase inhibition with fomepizole is contraindicated in hand sanitizer ingestions, as toxicity from ethanol or propanols will be prolonged without added benefit.

Our case report describes an immunosuppressed patient with ingestion of an ethanol-based hand sanitizer through a gastrostomy tube that resulted in a life-threatening intoxication. Dialysis was instituted because of his persistent coma and the increasing serum osmolality after the ingestion (Figure 1). This therapy is controversial but has been shown to shorten the duration of coma, time of removal from mechanical ventilation and to ameliorate the metabolic risks from prolonged blood ethanol exposure (18-21). Delayed and prolonged absorption in this case may have resulted from the high ethanol content of the sanitizer and from the excipient effects on gastric motility and/or diffusion across the intestinal lumen. Behenyl alcohol is a saturated long-chain (C22:0) fatty alcohol and one of the major excipients of the hand sanitizer. It is absorbed after ingestion in animal toxicity studies and while otherwise inert, may have contributed to an increase in unmeasured osmols (22).

The published case reports describe intentional ingestions that frequently occurred in the emergency department or psychiatric wards, with goals of intoxication or suicide. Our case report and those published in the literature suggest that intentional ingestions, particularly in the healthcare setting, may be associated with significant untoward events, including respiratory depression requiring intubation, metabolic disturbances necessitating dialysis, and death.

Based on NPDS data, reports of intentional hand sanitizer exposures have significantly increased from 2005 to 2009, but this data may under-represent the number of true exposures, especially if serious exposures or intoxications have not been reported to NPDS or if they occur outside of healthcare facilities. Although most out-of-hospital hand sanitizer exposures are unintentional and do not result in major toxicity, even a one-ounce bottle ingestion of the high ethanol content may pose a hazard if ingested by small children. A one-ounce ingestion of a hand sanitizer containing 62% ethanol by a 20 kg child results may result in a blood ethanol concentration of over 100 mg/dL. The large volume dispensers (500 ml) with high alcohol content (> 60% ethanol) typically used in healthcare settings, pose a potential serious risk if abused. These dispensers contain the equivalent alcohol content of two thirds of a standard size bottle (750 ml or a fifth of a gallon) of 120 proof distilled spirits.

Access to hand sanitizers should be monitored and potentially restricted in locations with at-risk patients, such as inpatient psychiatric units or correctional facilities. These concerns, however, must be balanced against the necessity to promote and maintain hand-hygiene practices in the healthcare setting. The easy access to hand sanitizers in the community and healthcare setting especially to persons with a history of substance abuse, risk-taking behavior or suicidal ideation dictates that health care providers be aware of their potential for abuse and the harm associated with this unique source of ethanol.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Support

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the Clinical Center, NIH, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, at the NIH, Bethesda, MD and the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System, Rocky Mountain Poison Center, Denver, CO.

These organizations provided material support for design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis of the data; and preparation of the manuscript.

This study was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-16):1–45. quiz CE41-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, et al. Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 27th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010. 2009;48(10):979–1178. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.543906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer P, Baudel JL, Maury E, et al. A surprising side effect of hand antisepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(11):1600. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2814-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts HS, Self RJ, Coxon M. An unusual complication of hand hygiene. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(1):100–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchet B, Charachon A, Lukat S, et al. A case of mixed intoxication with isopropyl alcohol and propanol-1 after ingestion of a topical antiseptic solution. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45(6):701–704. doi: 10.1080/15563650701517285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner SG. Changing dispensers may prevent intoxication from isopropanol and ethyl alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(4):486. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archer JR, Wood DM, Tizzard Z, et al. Alcohol hand rubs: hygiene and hazard. BMJ. 2007;335(7630):1154–1155. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39274.583472.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavolacci MP, Marini H, Vanheste S, et al. A voluntary ingestion of alcohol-based hand rub. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(1):86–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emadi A, Coberly L. Intoxication of a hospitalized patient with an isopropanol-based hand sanitizer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):530–531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc063237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyon S, Welsh C. Intoxication of a prison inmate with an ethyl alcohol-based hand sanitizer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):529–530. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc063110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vujasinovic M, Kocar M, Kramer K, et al. Poisoning with 1-propanol and 2-propanol. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26(12):975–978. doi: 10.1177/0960327107087794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thanarajasingam G, Diedrich DA, Mueller PS. Intentional ingestion of ethanol-based hand sanitizer by a hospitalized patient with alcoholism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(10):1288–1289. doi: 10.4065/82.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bookstaver PB, Norris LB, Michels JE. Ingestion of hand sanitizer by a hospitalized patient with a history of alcohol abuse. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(23):2203–2204. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinmann D, Faber T, Auwarter V, et al. Acute intoxication with isopropanol. Anaesthesist. 2009;58(2):149–152. doi: 10.1007/s00101-008-1453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Wijkerslooth LRH, Heijnis AD, Lange R, et al. Fatale intoxicatie met het handdesinfectans Sterillium. PW Wetenschappelijk Platform. 2009;3(1):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry-Lagarrigue M, Charbonnier M, Bruneel F, et al. Severe alcohol hand rub overdose inducing coma, watch after H1N1 pandemic. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12(3):400–402. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vonghia L, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19(8):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanap M, Chapman MJ. Severe ethanol poisoning: a case report and brief review. Crit Care Resusc. 2003;5(2):106–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan DL, Durso MH, Rich BK, et al. Severe ethanol intoxication in an adolescent. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13(4):416–418. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atassi WA, Noghnogh AA, Hariman R, et al. Hemodialysis as a treatment of severe ethanol poisoning. Int J Artif Organs. 1999;22(1):18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildenauer R, Kobbe P, Waydhas C. Is the osmole gap a valuable indicator for the need of hemodialysis in severe ethanol intoxication? Technol Health Care. 2010;18(3):203–206. doi: 10.3233/THC-2010-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iglesias G, Hlywka JJ, Berg JE, et al. The toxicity of behenyl alcohol. I. Genotoxicity and subchronic toxicity in rats and dogs. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;36(1):69–79. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2002.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]