Abstract

Objective

To investigate associations of daily breakfast consumption (DBC) with demographic and lifestyle factors in 41 countries.

Methods

Design: Survey including nationally representative samples of 11–15 year olds (n = 204,534) (HBSC 2005–2006). Statistics: Multilevel logistic regression analyses

Results

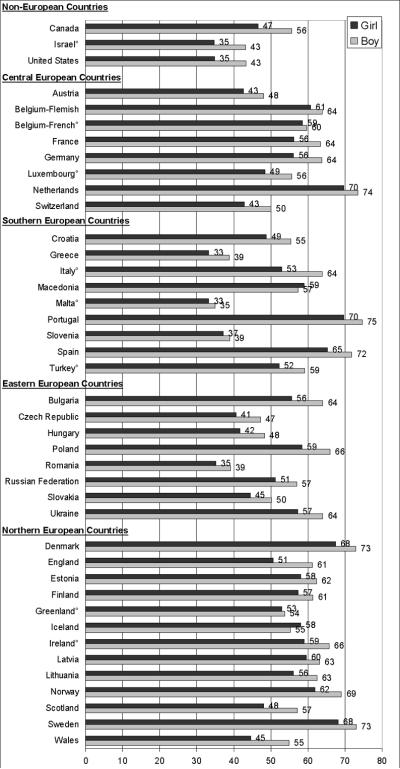

DBC varied from 33 % (Greek girls) to 75 % (Portuguese boys).

In most countries, lower DBC was noticed in girls, older adolescents, those with lower family affluence and those living in single-parent families. DBC was positively associated with healthy lifestyle behaviours and negatively with unhealthy lifestyle behaviours.

Conclusion

Breakfast skipping deserves attention in preventive programs. It is common among adolescents, especially girls, older adolescents and those from disadvantaged families.

The results indicate that DBC can serve as an indicator to identify children at risk for unhealthy lifestyle behaviours.

Keywords: Breakfast, Schoolchildren, Adolescents

Introduction

Breakfast is often considered the most important meal of the day and children can benefit from breakfast consumption in several ways. Several studies have consistently shown that regular breakfast consumption is associated with higher in-takes of micronutrients, and a better diet quality in school-aged children1–4. In addition, many cross-sectional studies across the world suggest an inverse relationship between breakfast consumption and BMI or overweight2–7. This finding has also been noted in the cross-sectional analysis of data from 41 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study (HBSC)8. Prospective studies have confirmed this association in adolescents2,9.

It is well known that parents play an important role in what children consume. The main body of literature on the association between social economic status (SES) and breakfast habits almost consistently concludes that being a child or adolescent of low SES is associated with irregular breakfast habits and this relationship exists for a range of different SES indicators (e. g. parental education2,10,11, parental occupation5, and area level indicators6). Only rarely, no association between SES and adolescent breakfast habits has been observed12. However most studies of the association between SES and adolescent breakfast habits have included US populations2,10 or Northern European populations5,11. Knowledge on the relevance of SES for the breakfast habits of children and adolescents in other European regions are lacking.

Health-compromising behaviours such as alcohol consumption, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle are also important determinants of energy balance and energy metabolism, and therefore need to be considered in the perspective of overweight prevention. Breakfast consumption is usually negatively associated with risk behaviours. Although, the relationship of breakfast consumption with these lifestyle factors has been examined in only a few studies5,7, to our knowledge, such data are lacking from a large cross-country comparative study perspective.

The purpose of the present study was to describe daily breakfast consumption (DBC) patterns of children across 41 countries participating in the HBSC (2005/06) survey and to identify its socio-demographic (gender, age, family affluence and family structure) and lifestyle correlates (smoking and drinking practices, physical activity, television viewing, eating habits including fruit, vegetable, soft-drink consumption, and dieting behaviour). Consistent patterns across the HBSC countries can make an important contribution to screening strategies and development of health promotion programs.

Methods

Subjects and study design

The data presented here were obtained from the 2005/06 World Health Organization collaborative HBSC study, which comprises of an international network of research teams across Europe and North America with the aim to gain insight into adolescents' health and health behaviours.

Each country followed the standardized international research protocol to ensure consistency in survey instruments, data collection and processing procedures. Participants were selected using a clustered sampling design, where the initial sampling unit was either the school class or school. Questionnaires were administered in school classrooms by trained personnel, teachers, or school nurses. The time frame for filling out the questionnaires was one school period. Participants could freely choose to participate and anonymity and confidentiality was ensured at all stages of the study. Each country respected ethical and legal requirements in their countries for this type of survey.

The population selected for sampling was 11, 13 and 15 years old attending school with the desired mean age for the three age groups being 11.5, 13.5 and 15.5 respectively. Participating countries were required to include a minimum of 95 % of the eligible target population within their sample frame. In the majority of countries, national representative samples were drawn and samples were stratified to ensure representation by, for example, geography, ethnic group and school type. The recommended sample size for each of the three age groups was approximately 1,500 students, assuming a 95 % confidence interval of +/− 3 percent around a proportion of 50 per cent and allowing for the clustered nature of the samples.

In total, 204,534 adolescents from 41countries or regions, were included in the 2005–06 final datafile. More detailed information about the study is provided elsewhere13,14.

Measures

To assess DBC, adolescents were asked to indicate how many days in a week and in a weekend they had breakfast (defined as having more than a glass of milk or fruit juice). Response categories were “never” to “five days” for the week, and “never” to “two days” for the weekend. The number of weekdays and weekend days were summed and dichotomized into “daily breakfast consumption” versus “less than daily”.

As a measure of the adolescents' socioeconomic position, family affluence was measured by a sum score (Family Affluence Scale: FAS) of four items: Does your family own a car, van or truck? (0–2 points). Do you have your own bedroom for yourself? (0–1 points). During the past twelve months, how many times did you travel away on holiday (vacation) with your family? (0–2 points); and how many computers does your family own? (0–2). Due to international differences in variation and mean of FAS, and the fact that we wanted to study the associations within each country rather than between countries, the FAS sum score was divided into tertiles within each country.

Some young people live in one or two parent households, while others may have more complex living arrangements. In the questions about family structure the child was asked to indicate on a checklist with whom he/she lived most of the time and if he/she also had a second home. The checklist included father, mother, stepfather, stepmother, siblings, extended family, living with other adults, or living in a foster home or children's home. The variables were combined and a distinction was made between those living with two parents (parents and/or stepparents) and those living with a single parent in the main home. Missings and those living in other family structures (e. g. in a foster home or with grand parents) were categorized into a third category to avoid losing these cases in further analyses.

To study the associations of DBC with health risk behaviours, questions on different aspects of lifestyle were included: substance use (smoking, drunkenness), physical activity, television viewing, eating habits (fruit, vegetable and soft drink consumption) and dieting practises. For each, a dichotomous variable was constructed.

Smoking status was defined based on the question “How often do you smoke tobacco at present?” Possible responses were: “every day”, “at least once a week, but not every day”, “less than once a week” or “never”, recoded into “smokers” and “non-smokers”. Alcohol (mis)use was measured with the question “How often have you been drunk?”, with the response options “never”, “once”, “2–3 times”, “4–10 times” and “more than 10 times”, recoded into “less than twice”, versus “twice or more”.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity was measured based on the question: “How many days in the past week were you physically active for 60 minutes or more. Response categories were “0 days” up to “7 days”, recoded into “< 5 days a week”; “≥ 5 days a week”.

Television viewing was assessed by “About how many hours a day do you usually watch television (including videos and DVDs) in your free time?” on weekdays and again on the weekend. The nine possible responses were “none at all”, “about half an hour a day”, “about 1 hour a day”, “about 2 hours a day” up to “about 7 or more hours a day”. Both responses were combined and recoded into “≤ 2 hours a day” versus “> 2 hours a day”.

Adolescents were asked how many times a week they usually consume fruit, vegetables, and soft drinks. The response options were “never”, “less than once a week”, “about once a week”, “two to four days a week”, “five to six days a week”, “once a day, every day”, “every day, more than once”. All three items were dichotomised into “daily” vs. “less than daily”.

Concerning dieting, adolescents were asked: “At present are you on a diet or doing something else to lose weight?” Response categories were: “no, my weight is fine”, “no, but I need to lose weight”, ”no, I need to put on weight” and “yes”, dichotomised into “dieters (= the last option)” and “non-dieters.”

Respondents with missing data on age, gender, family affluence or DBC were excluded from the analyses.

Analyses

Frequencies of DBC by gender were produced for all participating countries and for descriptive sake are presented by region as defined by the United Nations15.

Multilevel logistic regression analyses were conducted for each country separately, with adolescents nested within schools (two-level random intercept model). In a first set of models, the dependent variable was DBC and the independent variables were age, gender, family affluence and family structure. In a second set of analyses, we analysed for each health risk behaviour (independent) separately, the association with DBC (dependent), controlling for socio-demographic factors.

The Mlwin2.1 software package with second order predictive quasi-likelihood estimation procedures was used to perform the analyses. All independent variables are presented as dummy indicator variables, contrasted against a base category. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Data on 190,635 adolescents were included for the present analyses. Across all countries, 7.4 % of the respondents were excluded due to missing values on key variables: DBC (3.6 %), family affluence (3.7 %), and/or age (0.7 %). In eight countries > 10 % individuals were excluded due to missing values: Greenland (28.6 %), Israel (18.9 %), Luxembourg (16.8 %), Malta (14.9 %), Belgium-Fr (14.5 %), Italy (13.6 %), Ireland (11.8 %), and Turkey (11.3 %).

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Tab. 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population.

| Gender(%) | Age (y) (%) | Family Affluence (%) | Family Structure (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Boy | Girl | 11 | 13 | 15 | High | Medium | Low | 2-parent | Single | Other | N | |

| Non-European countries | ||||||||||||

| Canada | 47 | 53 | 24 | 35 | 40 | 23 | 55 | 23 | 78 | 18 | 5 | 5513 |

| Israel | 39 | 61 | 29 | 32 | 39 | 36 | 41 | 23 | 86 | 9 | 4 | 4610 |

| United States | 47 | 53 | 28 | 39 | 33 | 26 | 49 | 25 | 71 | 25 | 5 | 3769 |

| Central European countries | ||||||||||||

| Austria | 48 | 52 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 42 | 27 | 31 | 82 | 14 | 4 | 4393 |

| Belgium-Fl | 50 | 50 | 31 | 32 | 37 | 21 | 51 | 28 | 81 | 13 | 6 | 3937 |

| Belgium-Fr | 51 | 49 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 44 | 23 | 33 | 80 | 16 | 4 | 3829 |

| France | 49 | 51 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 23 | 51 | 26 | 82 | 15 | 4 | 6688 |

| Germany | 50 | 50 | 30 | 34 | 36 | 22 | 49 | 30 | 81 | 15 | 3 | 6876 |

| Luxembourg | 48 | 52 | 29 | 36 | 36 | 31 | 29 | 40 | 83 | 14 | 3 | 3652 |

| Netherlands | 50 | 50 | 32 | 35 | 32 | 23 | 55 | 22 | 86 | 12 | 1 | 4079 |

| Switzerland | 49 | 51 | 32 | 35 | 33 | 19 | 55 | 26 | 84 | 12 | 3 | 4321 |

| Southern European Countries | ||||||||||||

| Croatia | 48 | 52 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 22 | 48 | 30 | 90 | 8 | 1 | 4729 |

| Greece | 47 | 53 | 29 | 32 | 39 | 28 | 47 | 25 | 87 | 11 | 2 | 3537 |

| Italy | 48 | 52 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 34 | 25 | 41 | 89 | 8 | 3 | 3412 |

| Macedonia | 49 | 51 | 31 | 33 | 36 | 37 | 24 | 40 | 92 | 6 | 2 | 5016 |

| Malta | 47 | 53 | 37 | 37 | 27 | 38 | 27 | 35 | 65 | 35 | 1 | 1195 |

| Portugal | 47 | 53 | 30 | 34 | 36 | 33 | 43 | 24 | 82 | 10 | 8 | 3705 |

| Slovenia | 49 | 51 | 33 | 36 | 31 | 46 | 27 | 28 | 88 | 10 | 2 | 4841 |

| Spain | 49 | 51 | 33 | 32 | 35 | 40 | 27 | 33 | 86 | 11 | 3 | 8612 |

| Turkey | 51 | 49 | 37 | 33 | 31 | 31 | 38 | 31 | 79 | 10 | 12 | 5000 |

| Eastern European countries | ||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | 49 | 51 | 33 | 32 | 35 | 43 | 25 | 32 | 83 | 13 | 4 | 4505 |

| Czech Republic | 50 | 50 | 31 | 34 | 35 | 24 | 47 | 30 | 83 | 16 | 2 | 4647 |

| Hungary | 48 | 52 | 31 | 35 | 34 | 25 | 47 | 28 | 82 | 16 | 2 | 3397 |

| Poland | 48 | 52 | 28 | 30 | 42 | 24 | 44 | 32 | 86 | 12 | 3 | 5295 |

| Romania | 45 | 55 | 36 | 29 | 35 | 33 | 39 | 28 | 57 | 34 | 9 | 4350 |

| Russian Federation | 47 | 53 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 29 | 45 | 26 | 64 | 19 | 18 | 7523 |

| Slovakia | 46 | 54 | 33 | 35 | 33 | 32 | 44 | 25 | 87 | 12 | 1 | 3576 |

| Ukraine | 46 | 54 | 29 | 34 | 37 | 44 | 25 | 32 | 78 | 18 | 4 | 4756 |

| Northern European countries | ||||||||||||

| Denmark | 48 | 52 | 37 | 36 | 28 | 20 | 58 | 23 | 70 | 17 | 13 | 5280 |

| England | 47 | 53 | 33 | 35 | 31 | 32 | 28 | 39 | 80 | 16 | 4 | 4325 |

| Estonia | 49 | 51 | 32 | 32 | 36 | 25 | 44 | 32 | 80 | 19 | 2 | 4337 |

| Finland | 47 | 53 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 42 | 28 | 31 | 82 | 16 | 3 | 5015 |

| Greenland | 47 | 53 | 35 | 35 | 30 | 24 | 43 | 34 | 58 | 27 | 16 | 976 |

| Iceland | 50 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 20 | 38 | 33 | 28 | 82 | 16 | 3 | 8986 |

| Ireland | 50 | 51 | 29 | 36 | 35 | 20 | 56 | 23 | 83 | 12 | 5 | 4315 |

| Latvia | 47 | 53 | 33 | 35 | 32 | 22 | 46 | 32 | 72 | 23 | 5 | 3970 |

| Lithuania | 51 | 49 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 40 | 23 | 38 | 78 | 18 | 3 | 5362 |

| Norway | 51 | 49 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 31 | 76 | 15 | 9 | 4461 |

| Scotland | 49 | 51 | 28 | 36 | 36 | 44 | 24 | 32 | 78 | 19 | 3 | 5690 |

| Sweden | 49 | 51 | 34 | 31 | 35 | 25 | 31 | 44 | 82 | 14 | 5 | 4172 |

| Wales | 49 | 52 | 32 | 36 | 33 | 45 | 25 | 30 | 77 | 19 | 4 | 3983 |

When DBC patterns by countries and gender were examined (Fig. 1) regional tendencies were noted. The majority of Central European, Southern European, and Northern European countries had > 50 % children reporting DBC (highest DBC was noted in the Netherlands, Portugal, Denmark and Sweden). In half of the Eastern European and two of the three non-European countries, less than 50 % of children had breakfast every day.

Figure 1. Daily breakfast consumption among 11-, 13- and 15-year olds by country and gender (%).

°countries with more than 10% missings for breakfast consumption, family affluence or age

In most countries a general trend of lower DBC by girls (Tab. 2 and Fig. 1; exception Iceland), and a consistent trend of lower DBC in older age groups was noted, irrespective of region. Socio-economic position as measured by FAS, was associated with DBC in most Northern European and Central European countries; children from families with low FAS were less likely to have breakfast every day. However, a negative association between FAS and DBC was noted in three countries (Latvia, Bulgaria, Turkey). With regard to family structure, living in a two-parent family was associated with DBC in the majority of countries across regions with the exception of Eastern European countries.

Table 2.

Associations of daily breakfast consumption with socio-demographic factors: OR (95 %CI).

| Gender | Age (y) | Family affluence | Family structure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| girls | 13 | 15 | medium | low | single | other | |

| Non-European countries | |||||||

| Canada | 0.67 (0.60–0.75) | 0.48 (0.41–0.56) | 0.34 (0.28–0.41) | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) | 0.84 (0.71–1.00) | 0.62 (0.54–0.73) | 1.06 (0.80–1.39) |

| Israel | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) | 0.51 (0.43–0.62) | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 0.84 (0.68–1.04) | 1.05 (0.77–1.43) |

| United States | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) | 0.61 (0.52–0.72) | 0.50 (0.42–0.60) | 0.78 (0.67–0.92) | 0.61 (0.51–0.74) | 0.77 (0.66–0.91) | 0.67 (0.48–0.94) |

| Central European countries | |||||||

| Austria | 0.82 (0.72–0.93) | 0.64 (0.54–0.76) | 0.47 (0.39–0.56) | 0.93 (0.08–1.09) | 0.86 (0.75–1.00) | 0.79 (0.66–0.95) | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) |

| Belgium-Flemish | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 0.56 (0.45–0.68) | 0.38 (0.31–0.47) | 0.82 (0.68–0.98) | 0.58 (0.48–0.71) | 0.67 (0.55–0.81) | 0.72 (0.54–0.96) |

| Belgium-French | 0.96 (0.84–1.10) | 0.64 (0.52–0.78) | 0.45 (0.36–0.56) | 0.76 (0.64–0.90) | 0.66 (0.56–0.77) | 0.83 (0.69–0.99) | 1.06 (0.74–1.52) |

| France | 0.74 (0.67–0.82) | 0.62 (0.54–0.71) | 0.42 (0.37–0.48) | 0.86 (0.75–0.98) | 0.64 (0.55–0.74) | 0.79 (0.69–0.92) | 0.80 (0.61–1.04) |

| Germany | 0.73 (0.66–0.81) | 0.50 (0.44–0.57) | 0.40 (0.35–0.45) | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | 0.55 (0.47–0.64) | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | 0.69 (0.52–0.91) |

| Luxembourg | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) | 0.60 (0.50–0.72) | 0.41 (0.34–0.50) | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | 0.71 (0.60–0.84) | 0.72 (0.59–0.87) | 0.83 (0.56–1.23) |

| Netherlands | 0.83 (0.72–0.96) | 0.51 (0.41–0.65) | 0.30 (0.23–0.38) | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | 0.77 (0.62–0.97) | 0.64 (0.52–0.80) | 1.05 (0.58–1.91) |

| Switzerland | 0.74 (0.66–0.84) | 0.62 (0.52–0.74) | 0.44 (0.37–0.52) | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.69 (0.57–0.83) | 0.73 (0.60–0.88) | 0.84 (0.59–1.19) |

| Southern European Countries | |||||||

| Croatia | 0.78 (0.69–0.88) | 0.67 (0.58–0.77) | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) | 0.94 (0.55–1.58) |

| Greece | 0.81 (0.70–0.93) | 0.69 (0.56–0.85) | 0.54 (0.44–0.66) | 0.91 (0.77–1.08) | 0.89 (0.73–1.09) | 0.90 (0.71–1.13) | 1.29 (0.81–2.06) |

| Italy | 0.63 (0.55–0.73) | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) | 0.54 (0.43–0.69) | 0.97 (0.80–1.17) | 0.87 (0.73–1.03) | 0.70 (0.55–0.91) | 1.23 (0.80–1.90) |

| Macedonia | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | 1.07 (0.92–1.25) | 0.81 (0.61–1.08) | 1.25 (1.06–1.47) | 1.00 (0.87–1.16) | 0.88 (0.69–1.14) | 0.63 (0.41–0.96) |

| Malta° | 0.88 (0.69–1.13) | 0.79 (0.60–1.05) | 0.59 (0.43–0.81) | 0.73 (0.53–0.99) | 0.96 (0.72–1.27) | 0.74 (0.57–0.96) | 0.91 (0.23–3.56) |

| Portugal | 0.80 (0.69–0.93) | 0.66 (0.54–0.82) | 0.32 (0.26–0.39) | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) | 0.96 (0.79–1.18) | 0.71 (0.56–0.9) | 0.62 (0.48–0.81) |

| Slovenia | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 0.53 (0.46–0.62) | 0.54 (0.45–0.64) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | 0.80 (0.69–0.92) | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 1.30 (0.86–1.96) |

| Spain | 0.72 (0.65–0.79) | 0.51 (0.45–0.58) | 0.30 (0.26–0.34) | 0.87 (0.78–0.99) | 0.78 (0.70–0.88) | 0.71 (0.61–0.82) | 1.01 (0.77–1.32) |

| Turkey | 0.75 (0.67–0.85) | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) | 0.73 (0.61–0.88) | 1.23 (1.07–1.42) | 1.21 (1.04–1.41) | 0.78 (0.64–0.95) | 0.82 (0.69–0.99) |

| Eastern European countries | |||||||

| Bulgaria | 0.73 (0.64–0.83) | 0.63 (0.53–0.73) | 0.40 (0.34–0.48) | 1.18 (1.01–1.39) | 1.30 (1.12–1.52) | 0.87 (0.72–1.05) | 0.89 (0.65–1.22) |

| Czech Republic | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | 0.74 (0.64–0.86) | 0.66 (0.57–0.76) | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) | 0.89 (0.76–1.06) | 0.78 (0.66–0.92) | 0.96 (0.59–1.56) |

| Hungary | 0.77 (0.67–0.89) | 0.67 (0.56–0.79) | 0.46 (0.37–0.56) | 1.09 (0.91–1.29) | 0.89 (0.73–1.09) | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | 1.19 (0.74–1.91) |

| Poland | 0.73 (0.65–0.81) | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) | 0.62 (0.53–0.74) | 1.14 (0.98–1.32) | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) | 0.84 (0.70–1.00) | 1.15 (0.79–1.69) |

| Romania | 0.88 (0.77–1.00) | 0.76 (0.63–0.91) | 0.62 (0.51–0.75) | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.83 (0.70–0.99) | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) |

| Russian Federation | 0.79 (0.72–0.87) | 0.79 (0.71–0.89) | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 0.92 (0.82–1.04) | 1.07 (0.93–1.24) |

| Slovakia° | 0.80 (0.70–0.92) | 0.71 (0.60–0.83) | 0.66 (0.56–0.77) | 1.06 (0.91–1.24) | 0.91 (0.76–1.09) | 0.83 (0.67–1.02) | 0.54 (0.29–0.99) |

| Ukraine | 0.74 (0.66–0.84) | 0.94 (0.79–1.14) | 0.69 (0.57–0.82) | 1.08 (0.92–1.25) | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | 1.02 (0.86–1.19) | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) |

| Northern European countries | |||||||

| Denmark | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) | 0.57 (0.49–0.67) | 0.38 (0.33–0.45) | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 0.64 (0.54–0.75) | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) |

| England | 0.61 (0.53–0.70) | 0.58 (0.50–0.68) | 0.45 (0.38–0.53) | 0.93 (0.79–1.09) | 0.79 (0.68–0.92) | 0.75 (0.63–0.89) | 0.67 (0.48–0.92) |

| Estonia | 0.82 (0.73–0.93) | 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) | 1.11 (0.95–1.30) | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.94 (0.57–1.54) |

| Finland | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | 0.56 (0.48–0.66) | 0.43 (0.37–0.51) | 0.87 (0.75–1.00) | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) | 0.68 (0.58–0.80) | 0.79 (0.55–1.15) |

| Greenland | 0.94 (0.72–1.24) | 1.01 (0.73–1.41) | 0.41 (0.29–0.58) | 0.97 (0.68–1.39) | 0.79 (0.53–1.17) | 0.76 (0.55–1.05) | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) |

| Iceland | 1.14 (1.04–1.24) | 0.53 (0.48–0.59) | 0.31 (0.28–0.35) | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | 0.76 (0.68–0.84) | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) |

| Ireland | 0.70 (0.61–0.80) | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | 0.43 (0.35–0.52) | 0.95 (0.80–1.12) | 0.70 (0.57–0.85) | 0.68 (0.56–0.82) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) |

| Latvia | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | 0.82 (0.70–0.96) | 0.85 (0.73–1.00) | 1.22 (1.03–1.44) | 1.33 (1.11–1.60) | 0.86 (0.74–1.01) | 1.00 (0.73–1.36) |

| Lithuania | 0.76 (0.68–0.85) | 0.73 (0.63–0.83) | 0.62 (0.54–0.71) | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | 0.96 (0.85–1.10) | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | 1.26 (0.92–1.73) |

| Norway | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) | 0.52 (0.44–0.62) | 0.33 (0.28–0.40) | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) | 0.69 (0.59–0.82) | 0.66 (0.55–0.79) | 0.86 (0.68–1.08) |

| Scotland | 0.66 (0.60–0.74) | 0.40 (0.34–0.47) | 0.30 (0.25–0.35) | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) | 0.83 (0.73–0.95) | 0.66 (0.57–0.76) | 0.89 (0.65–1.22) |

| Sweden | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | 0.46 (0.38–0.57) | 0.31 (0.26–0.37) | 0.93 (0.77–1.13) | 0.78 (0.66–0.94) | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.73 (0.53–1.01) |

| Wales | 0.64 (0.56–0.72) | 0.61 (0.52–0.71) | 0.44 (0.37–0.52) | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.81 (0.69–0.94) | 0.79 (0.66–0.93) | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) |

no school variable was available, as a consequence the clustering in schools was not taken into account

base category: boys, 11 year old, high family affluence, living with 2 parents

bold: significant OR

The adjusted odds for DBC were lower in smokers in all countries, except Malta (Tab. 3). A negative association was also noted between DBC and being drunk in the majority of countries except in Southern European countries, where the association was less evident.

Table 3.

Associations of daily breakfast consumption with health-related behaviours: Adjusted OR (95 %CI).

| smokers | Alcohol misuse (been drunk ≥ 2 times) | Physical activity (≥ 5 days 60 minutes) | Television viewing (> 2 hours) | daily fruit consumption | daily vegetables consumption | daily soft drinks consumption | on a diet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-European countries | ||||||||

| Canada | 0.38 (0.31–0.47) | 0.46 (0.39–0.54) | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 0.76 (0.67–0.85) | 1.68 (1.49–1.89) | 1.65 (1.47–1.86) | 0.56 (0.47–0.66) | 0.67 (0.57–0.79) |

| Israel | 0.76 (0.60–0.97) | 0.81 (0.62–1.05) | 1.57 (1.37–1.80) | 0.78 (0.68–0.90) | 1.63 (1.49–1.79) | 1.50 (1.33–1.70) | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 0.73 (0.61–0.88) |

| United States | 0.49 (0.37–0.65) | 0.70 (0.54–0.92) | 1.33 (1.16–1.53) | 0.69 (0.60–0.79) | 1.49 (1.30–1.71) | 1.61 (1.40–1.85) | 0.72 (0.63–0.84) | 0.65 (0.55–0.77) |

| Central European countries | ||||||||

| Austria | 0.49 (0.41–0.59) | 0.43 (0.35–0.53) | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 0.64 (0.56–0.72) | 1.26 (1.10–1.43) | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | 0.62 (0.53–0.74) |

| Belgium-Fl. | 0.49 (0.40–0.61) | 0.51 (0.41–0.62) | 1.50 (1.30–1.74) | 0.62 (0.54–0.71) | 1.55 (1.34–1.79) | 1.70 (1.48–1.95) | 0.71 (0.62–0.81) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91) |

| Belgium-Fr. | 0.45 (0.35–0.57) | 0.69 (0.56–0.85) | 1.44 (1.25–1.65) | 0.65 (0.56–0.74) | 1.32 (1.16–1.51) | 1.39 (1.21–1.60) | 0.70 (0.61–0.81) | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) |

| France | 0.56 (0.48–0.66) | 0.58 (0.49–0.69) | 1.19 (1.06–1.33) | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) | 1.33 (1.19–1.49) | 1.46 (1.31–1.62) | 0.66 (0.59–0.74) | 0.65 (0.55–0.76) |

| Germany | 0.48 (0.41–0.56) | 0.5 (0.43–0.59) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | 0.70 (0.63–0.78) | 1.27 (1.14–1.42) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | 0.57 (0.49–0.67) |

| Luxembourg | 0.51 (0.41–0.63) | 0.54 (0.42–0.69) | 1.15 (0.99–1.32) | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 1.24 (1.07–1.43) | 0.67 (0.57–0.78) | 0.52 (0.43–0.63) |

| Netherlands | 0.37 (0.29–0.46) | 0.45 (0.36–0.57) | 1.39 (1.20–1.61) | 0.84 (0.71–0.98) | 1.41 (1.20–1.66) | 1.51 (1.30–1.76) | 0.72 (0.62–0.84) | 0.72 (0.56–0.94) |

| Switzerland | 0.50 (0.40–0.63) | 0.51 (0.40–0.65) | 1.29 (1.11–1.49) | 0.61 (0.53–0.70) | 1.28 (1.13–1.46) | 1.39 (1.22–1.58) | 0.67 (0.58–0.77) | 0.56 (0.46–0.68) |

| Southern European Countries | ||||||||

| Croatia | 0.61 (0.51–0.74) | 0.61 (0.52–0.72) | 1.41 (1.25–1.59) | 0.88 (0.77–1.00) | 1.50 (1.33–1.70) | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 0.56 (0.46–0.68) |

| Greece | 0.71 (0.53–0.93) | 0.78 (0.60–1.02) | 1.54 (1.33–1.79) | 0.83 (0.71–0.97) | 1.58 (1.36–1.84) | 1.52 (1.31–1.77) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91) | 0.87 (0.71–1.05) |

| Italy | 0.59 (0.47–0.73) | 0.89 (0.69–1.14) | 0.95 (0.82–1.11) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | 1.30 (1.13–1.51) | 1.45 (1.23–1.72) | 0.88 (0.75–1.04) | 0.60 (0.49–0.72) |

| Macedonia | 0.72 (0.56–0.91) | 1.01 (0.80–1.26) | 1.35 (1.19–1.53) | 1.18 (1.04–1.34) | 1.28 (1.13–1.45) | 1.41 (1.24–1.60) | 1.12 (0.98–1.27) | 0.48 (0.39–0.58) |

| Malta° | 0.78 (0.53–1.14) | 0.41 (0.22–0.74) | 1.61 (1.24–2.08) | 0.85 (0.73–0.99) | 1.56 (1.21–1.99) | 1.48 (1.05–2.11) | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.77 (0.57–1.04) |

| Portugal | 0.61 (0.48–0.77) | 0.78 (0.62–0.98) | 1.14 (0.96–1.36) | 0.83 (0.70–0.99) | 1.65 (1.41–1.93) | 1.69 (1.41–2.04) | 0.78 (0.66–0.92) | 0.63 (0.50–0.80) |

| Slovenia | 0.54 (0.42–0.68) | 0.64 (0.53–0.77) | 1.40 (1.23–1.58) | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | 1.14 (1.01–1.29) | 1.36 (1.18–1.56) | 0.87 (0.76–1.01) | 0.67 (0.55–0.80) |

| Spain | 0.51 (0.44–0.59) | 0.56 (0.48–0.66) | 1.21 (1.09–1.33) | 0.73 (0.66–0.80) | 1.37 (1.24–1.51) | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 0.65 (0.58–0.72) | 0.48 (0.42–0.56) |

| Turkey | NA | NA | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.87 (0.77–0.98) | 1.36 (1.20–1.54) | 1.61 (1.40–1.84) | 0.75 (0.64–0.87) | 0.46 (0.35–0.61) |

| Eastern European countries | ||||||||

| Bulgaria | 0.66 (0.55–0.78) | 0.70 (0.60–0.82) | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 1.04 (0.90–1.21) | 1.28 (1.11–1.46) | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 0.45 (0.37–0.54) |

| Czech Rep. | 0.55 (0.46–0.66) | 0.61 (0.51–0.73) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | 0.83 (0.74–0.94) | 1.29 (1.14–1.46) | 1.32 (1.16–1.51) | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | 0.69 (0.59–0.82) |

| Hungary | 0.63 (0.50–0.78) | 0.56 (0.45–0.69) | 1.26 (1.09–1.47) | 0.77 (0.67–0.89) | 1.47 (1.27–1.71) | 1.80 (1.52–2.14) | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | 0.78 (0.65–0.94) |

| Poland | 0.56 (0.47–0.67) | 0.58 (0.50–0.68) | 1.18 (1.05–1.33) | 0.79 (0.70–0.89) | 1.17 (1.04–1.33) | 1.48 (1.30–1.69) | 0.66 (0.58–0.75) | 0.52 (0.44–0.60) |

| Romania | 0.74 (0.58–0.95) | 0.82 (0.67–0.99) | 1.35 (1.17–1.55) | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | 1.41 (1.24–1.61) | 1.53 (1.33–1.76) | 0.84 (0.74–0.96) | 0.69 (0.55–0.85) |

| Russian Fed. | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) | 1.23 (1.11–1.36) | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) | 1.39 (1.26–1.54) | 0.91 (0.82–1.01) | 0.63 (0.55–0.72) |

| Slovakia° | 0.58 (0.47–0.72) | 0.59 (0.48–0.72) | 1.19 (0.99–1.30) | 0.85 (0.73–0.99) | 1.12 (0.97–1.29) | 1.34 (1.15–1.57) | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | 0.60 (0.48–0.75) |

| Ukraine | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) | 0.96 (0.82–1.13) | 1.29 (1.14–1.46) | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) | 1.22 (1.06–1.39) | 1.35 (1.20–1.53) | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | 0.61 (0.50–0.73) |

| Northern European countries | ||||||||

| Denmark | 0.40 (0.33–0.48) | 0.44 (0.37–0.52) | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 0.72 (0.63–0.82) | 1.20 (1.06–1.37) | 1.48 (1.30–1.69) | 0.44 (0.36–0.54) | 0.67 (0.58–0.78) |

| England | 0.42 (0.34–0.52) | 0.44 (0.37–0.52) | 1.30 (1.14–1.48) | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) | 1.59 (1.39–1.81) | 1.72 (1.51–1.97) | 0.61 (0.52–0.71) | 0.50 (0.42–0.60) |

| Estonia | 0.66 (0.55–0.78) | 0.70 (0.59–0.82) | 1.52 (1.34–1.74) | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 1.12 (0.97–1.28) | 1.35 (1.16–1.58) | 0.77 (0.63–0.95) | 0.65 (0.51–0.82) |

| Finland | 0.41 (0.34–0.49) | 0.43 (0.36–0.51) | 1.34 (1.18–1.52) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | 1.63 (1.42–1.88) | 0.48 (0.37–0.63) | 0.77 (0.63–0.93) |

| Greenland | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | 0.76 (0.51–1.14) | 1.45 (1.10–1.92) | 0.99 (0.71–1.39) | 0.89 (0.60–1.33) | 1.10 (0.83–1.47) | 0.57 (0.42–0.78) | 0.91 (0.64–1.31) |

| Iceland | 0.32 (0.26–0.40) | 0.40 (0.33–0.48) | 1.60 (1.47–1.75) | 0.71 (0.65–0.77) | 1.43 (1.30–1.57) | 1.66 (1.50–1.84) | 0.45 (0.39–0.52) | 0.62 (0.55–0.68) |

| Ireland | 0.41 (0.33–0.50) | 0.44 (0.36–0.53) | 1.31 (1.14–1.50) | 0.73 (0.64–0.83) | 1.63 (1.42–1.88) | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 0.52 (0.45–0.61) | 0.50 (0.41–0.61) |

| Latvia | 0.60 (0.51–0.72) | 0.62 (0.52–0.73) | 1.19 (1.04–1.36) | 0.89 (0.78–1.03) | 0.98 (0.83–1.14) | 1.24 (1.06–1.45) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.64 (0.52–0.78) |

| Lithuania | 0.72 (0.61–0.85) | 0.69 (0.60–0.80) | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) | 0.90 (0.80–1.02) | 1.05 (0.92–1.20) | 1.28 (1.12–1.46) | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | 0.45 (0.38–0.54) |

| Norway | 0.34 (0.27–0.43) | 0.43 (0.34–0.53) | 1.40 (1.22–1.61) | 0.69 (0.60–0.79) | 1.48 (1.30–1.70) | 1.54 (1.33–1.79) | 0.41 (0.34–0.50) | 0.52 (0.43–0.62) |

| Scotland | 0.46 (0.38–0.56) | 0.53 (0.46–0.61) | 1.26 (1.13–1.41) | 0.82 (0.74–0.92) | 1.89 (1.69–2.13) | 1.76 (1.57–1.98) | 0.54 (0.48–0.62) | 0.65 (0.56–0.75) |

| Sweden | 0.28 (0.21–0.38) | 0.37 (0.30–0.47) | 1.28 (1.10–1.48) | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) | 1.43 (1.22–1.67) | 1.39 (1.19–1.61) | 0.37 (0.28–0.48) | 0.44 (0.35–0.56) |

| Wales | 0.46 (0.37–0.57) | 0.52 (0.45–0.61) | 1.38 (1.21–1.58) | 0.88 (0.77–1.01) | 1.58 (1.38–1.82) | 1.66 (1.44–1.91) | 0.61 (0.53–0.70) | 0.70 (0.59–0.82) |

no school variable was available, as a consequence the clustering in schools was not taken into account; NA = not available all analyses controlled for gender, age, family affluence and family structure bold = significant OR

In the majority of countries, being physically active was positively, while watching > 2 hr/day of television was negatively associated with DBC. Most countries showed a strong positive relation between daily fruit or vegetable consumption and DBC. In addition, in most countries soft drink consumption and dieting were negatively associated with DBC.

Discussion

Despite the recommendations encouraging breakfast consumption4, breakfast skipping by children was noted consistently across all regions. In only four countries (Netherlands, Portugal, Denmark, and Sweden) 70 % or more children reported eating breakfast daily. This is consistent with the findings indicating that breakfast skipping is highly prevalent in Europe and the United States, ranging from 10 to 30 %4. Variations in DBC were noted across regions. Disparities in breakfast consumption across countries may be explained by differences in cultural practices, socio-economic factors and availability of school-breakfast programs.

DBC was related to all socio- demographic factors examined. Girls showed lower prevalences of DBC than boys in most countries. DBC was less common in older children, and in children from families with lower family affluence, and in those living with a single parent. In addition, DBC correlated positively with healthy lifestyle- and negatively with unhealthy lifestyle-behaviours.

The finding of girls eating breakfast less often than boys has been reported previously5,6,12,16. It is likely that girls are more weight and/or image-conscious and are more likely to practice weight control behaviours including breakfast skipping17. In fact, dieting related negatively to DBC in the current study (adjusted OR ranged between 0.44 and 0.91) consistent with the findings of Timlin et al.2. Our finding of lower DBC in older children compared to 11 year olds is also consistent with previous studies6,9. This age-related decline in DBC could be explained by important changes that accompany adolescence including greater autonomy and independence in food choices, decreased frequency of family meals and time considerations3,18 but also increased dieting, especially among girls. Previous studies on the association between SES and breakfast habits in US populations2,10 and Northern European populations5,11 indicate a positive association between SES and regular breakfast consumption. However, the present study indicates that the association of SES, operationalised as family affluence, with DBC shows regional differences that could reflect differences in socio-cultural norms regarding breakfast consumption.

Literature on the association between family structure and breakfast habits of children and adolescents is limited11,16. Our findings that irregular breakfast habits occur more often among children of single-parent families compared to two-parent family constellations, generally fit well with those reported previously11,16. This finding was consistent across regions except for countries from the Eastern European region, where sociocultural norms may be different. However, whether family structure is the direct cause of adverse life outcomes has been disputed19. It is likely that single parent families may represent a cluster of several social and contextual factors that may be mediating its association with negative outcomes20.

Adolescence is often characterized by increased risk behaviour and experimentation with alcohol, tobacco and other drugs. In the current study, DBC was negatively correlated with smoking in all but one country, illustrating the consistency of this association across socio-economic, cultural, and regional differences. This finding is in agreement with other reports showing a consistent inverse association between breakfast consumption and smoking2,5. A plausible link between smoking and skipping breakfast may be that smoking diminishes appetite5; another explanation might be the clustering of unhealthy behaviours. Alcohol consumption has also been associated with skipping breakfast in adolescents2,5. In the current study children who reported being drunk at least twice in their life had decreased odds of DBC in the majority of countries except in Southern European countries where this association was less evident.

Few studies have examined the association between breakfast consumption and physical activity: congruent with our findings, most reported a positive association2,5,7 while one study6 involving younger children (5–14 y) found no relation. Our results on the association of DBC with sedentary behaviour fit well with our findings on DBC and physical activity: children who consumed breakfast daily were also less likely to watch > 2 hours/day of television. To our knowledge this is the first study to report on the association between breakfast consumption and television viewing, although television use has often been related to overweight in children and adolescents21.

In the current study, in most countries with the exception of some Northern European countries, both daily fruit and daily vegetable consumption were consistently associated with DBC whereas an inverse relationship was found for daily soft drink consumption in most countries. In two other studies comparable findings have been noted1,6.

Our study has certain limitations. The school response was low for some countries which might compromise the generalizability of the findings (i. e. < 60 % for Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, the USA, and Wales; > 60 and < 75 % for Norway and Greenland; for 6 countries/regions the data was not available; > 75 % for the remaining 28 countries). Nevertheless, we have no reason to believe that their refusal to participate has an important influence on the results of our analyses as the reason for drop out is mainly that they already participate in one or several other studies. The pupil response was in general high, varying between 73 and 96 % for those countries of which information was available (n = 22). Additionally it must be said that it is difficult to compare the response rates between the countries because the available information on the gross population is very different from country to country.

The data were self-reported. Furthermore, DBC was based on frequency of breakfast during the week (defined as more than a glass of milk or fruit juice), however no further information on the quality of breakfast was gathered. Nonetheless the quality of breakfast could be important in determining its health effects1.

Taken together, the findings from this large, multi-national survey involving simultaneous assessment of several domains (socio-economic, demographic, and several health related lifestyle behaviours) in 11-, 13- and 15-year old children, indicate that a simple definition of breakfast consumption can serve as an indicator to identify children at risk for unhealthy lifestyle behaviours. These children could be targeted for interventions to improve overall lifestyle practises.

Another important message from this study is to promote breakfast consumption in children. Although some studies suggest that breakfast consumption 4–5 times a week is already associated with health benefits, others have shown that breakfast consumption has a dose-response effect on overweight2. Thus DBC should be encouraged as much as possible within the context of each country and family. Increased attention to DBC is necessary during the transition from childhood to adolescence, especially in girls and young persons from disadvantaged families. Breakfast provision in schools may offer a means to overcome social inequalities in DBC and could serve to yield health benefits associated with breakfast consumption.

Acknowledgement

HBSC is an international study carried out in collaboration with WHO/EURO. The international coordinator of the 2001–2002 and 2005–2006 study was Candace Currie, University of Edinburgh, Scotland; and the data bank manager was Oddrun Samdal, University of Bergen, Norway. A complete list of the participating researchers can be found on the HBSC website (www.HBSC.org).

Carine Vereecken is post-doctoral researcher funded by the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO). Marie Dupuy is a doctoral student under the supervision of Namanjeet Ahluwalia; this work reflects part of Marie Dupuy's doctoral dissertation research.

References

- 1.Matthys C, De Henauw S, Bellernans M, De Maeyer M, De Backer G. Breakfast habits affect overall nutrient profiles in adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:413–21. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007248049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timlin MT, Pereira MA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Breakfast eating and weight change in a 5-year prospective analysis of adolescents: Project EAT (eating among teens) Pediatrics. 2008:E638–E645. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Affenito SG. Breakfast: a missed opportunity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:565–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, Adams J, Metzl JD. Review – Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:743–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keski-Rahkonen A, Kaprio J, Rissanen A, Virkkunen M, Rose RJ. Breakfast skipping and health-compromising behaviors in adolescents and adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:842–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Utter J, Scragg R, Mhurchu CN, Schaaf D. At-home breakfast consumption among New Zealand children: associations with body mass index and related nutrition behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang RJ, Wang EK, Hsieh YS, Chen MY. Irregular breakfast eating and health status among adolescents in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haug E, Rasmussen M, Samdal O, et al. Over-weight in school-aged children and its relationship with demographic and lifestyle factors: results from the WHO-Collaborative Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study. Int J Public Health. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5408-6. DOI: 10.1007/s00038-009-5408-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:842–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delva J, O'Malley PA, Johnston LD. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic status differences in overweight and health-related behaviors among American students: national trends 1986–2003. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:536–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansen A, Rasmussen S, Madsen M. Health behaviour among adolescents in Denmark: influence of school class and individual risk factors. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34:32–40. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw ME. Adolescent breakfast skipping: an Australian study. Adolescence. 1998;33:851–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts C, Currie C, Samdal O, Currie D, Smith R, Maes L. Measuring the health and health behaviours of adolescents through cross-national survey research: recent developments in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. J Public Health. 2007;15:179–96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts C, Freeman J, Samdal O, et al. MDG and the HBSC study group The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: methodological developments and current tensions. Int J Public Health. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5405-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00038-009-5405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations [Accessed January, 31, 2008];United Nation Statistics Divisions. (at http://unstats_un org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin htm)

- 16.Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM, Carson T. Trends in breakfast consumption for children in the United States from 1965 to 1991. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:748S–756S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.4.748S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss RS. Self-reported weight status and dieting in a cross-sectional sample of young adolescents – National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:741–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C, Casey MA. Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:929–37. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipman EL, Boyle MH, Dooley MD, Offord DR. Child well-being in single-mother families. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:75–82. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1089–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenmann JC, Bartee RT, Wang MQ. Physical activity, TV viewing, and weight in U.S. youth: 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Obes Res. 2002;10:379–385. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]