Summary

Translational control of mRNAs in dendrites is essential for certain forms of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. CPEB is an RNA-binding protein that regulates local translation in dendrites. Here, we identify poly(A) polymerase Gld2, deadenylase PARN, and translation inhibitory factor neuroguidin (Ngd) as components of a dendritic CPEB-associated polyadenylation apparatus. Synaptic stimulation induces phosphorylation of CPEB, PARN expulsion from the ribonucleoprotein complex, and polyadenylation in dendrites. A screen for mRNAs whose polyadenylation is altered by Gld2 depletion identified >100 transcripts including one encoding NR2A, an NMDA receptor subunit. shRNA depletion studies demonstrate that Gld2 promotes and Ngd inhibits dendritic NR2A expression. Finally, shRNA-mediated depletion of Gld2 in vivo attenuates protein synthesis-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) at hippocampal dentate gyrus synapses; conversely Ngd depletion enhances LTP. These results identify a pivotal role for polyadenylation and the opposing effects of Gld2 and Ngd in hippocampal synaptic plasticity.

Introduction

Spatial control of mRNA translation is critical for diverse cellular functions across species (Besse and Ephrussi, 2008). In the mammalian nervous system, experience-induced modifications of synaptic connections (synaptic plasticity) are thought to underlie learning and memory (Kandel, 2001). These modifications require activity-dependent protein synthesis, which likely involves specific mRNA translation at or near synapses (Sutton and Schuman 2006). In the hippocampus, protein synthesis is required for multiple forms of synaptic plasticity including late-phase long term potentiation (L-LTP), neurotrophin-induced LTP, and metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated long term depression (mGluR-LTD) (Krug et al., 1984; Frey et al., 1988; Kang and Schuman, 1996; Huber et al., 2000). In the latter two cases, protein synthesis was required in the dendrite-rich stratum radiatum even after it had been severed from the cell body layer. These studies point to the importance of activity-dependent dendritic translation for synaptic plasticity (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009; Richter and Klann, 2009; Sutton and Schuman, 2006). Indeed, dendrites harbor mRNAs (Poon et al., 2006), ribosomes (Steward and Levy, 1982), micro-RNAs, and RISC (Schratt, 2009), supporting the notion of synaptic activity-induced local protein synthesis.

One protein involved in neuronal mRNA translation is CPEB (Wu et al., 1998), which binds the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) and modulates poly(A) tail length. In Xenopus oocytes, CPEB associates with several factors including: (i) cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF), which binds the hexanucleotide AAUAAA, (ii) Gld2, a poly(A) polymerase, (iii) PARN, a deadenylating enzyme, (iv) maskin, which interacts with the cap-binding factor eIF4E, and (v) symplekin, a scaffold protein upon which the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is assembled (Richter, 2007). When tethered to mRNAs by CPEB, PARN activity is dominant to that of Gld2, leading to poly(A) tail shortening of CPE-containing mRNAs (Barnard et al., 2004; Kim and Richter, 2006). Upon stimulation of oocytes to re-enter meiosis, Aurora A phosphorylates CPEB leading to expulsion of PARN from the RNP complex and polyadenylation by Gld2. The poly(A) tail serves as a platform for poly(A) binding protein, which binds eIF4G and helps it displace maskin from eIF4E and recruit the 40S ribosomal subunit to the mRNA (Kim and Richter, 2006; Stebbins-Boaz et al., 1999).

In the brain, CPEB regulates synaptic plasticity and hippocampal-dependent memories (Alarcon et al., 2004; Berger-Sweeney et al., 2006; Zearfoss et al., 2008). N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) activation promotes CPEB phosphorylation (Atkins et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2002), triggering mRNA-specific polyadenylation and translation (Huang et al., 2002; McEvoy et al., 2007; Wu et al., 1998). Although CPEB stimulates polyadenylation in neurons, the mechanism by which it does so and whether polyadenylation occurs in dendrites are unknown. CPEB can repress translation without influencing polyadenylation (Groisman et al., 2006) and modulate alternative splicing (Lin et al., 2009) indicating that cytoplasmic 3′ end processing does not necessarily affect plasticity. Finally, maskin is not detected in mammals, implicating other factors in CPEB-mediated translation. In this regard, mammalian neurons contain neuroguidin (Ngd), a CPEB and eIF4E-binding protein that may function in a manner analogous to maskin (Jung et al., 2006).

The nexus of observations showing that CPEB is synapto-dendritic, that it modulates plasticity, and that local protein synthesis is necessary for LTP and LTD suggests that cytoplasmic polyadenylation could mediate local protein synthesis and synaptic efficacy. To investigate this possibility, we focused on factors that control polyadenylation/translation and found that CPEB, symplekin, Gld2, PARN, and Ngd formed a complex in hippocampal dendrites. NMDA stimulation promoted CPEB phosphorylation and expulsion of PARN from the complex, and induced a rapid increase in dendritic poly(A) that was attenuated by Gld2 depletion or inhibition of CPEB phosphorylation. A screen for neuronal mRNAs whose polyadenylation is influenced by Gld2 identified several transcripts including one for NR2A, an NMDAR subunit. Depletion of Gld2 and Ngd toggled the expression of this dendritically-localized mRNA. Moreover, knockdown of Gld2 in vivo inhibited theta-burst stimulation (TBS)-induced LTP at dentate gyrus (DG) granule cell synapses, while depletion of Ngd increased the magnitude of the LTP. These and other findings indicate that the cytoplasmic polyadenylation machinery bidirectionally regulates mRNA-specific translation and plasticity at hippocampal synapses, which we suggest represents a coherent molecular mechanism that underlies essential brain function.

Results

Interaction and Co-localization of CPEB Complex Proteins in Neurons

The distribution of CPEB, Gld2, PARN, symplekin, and Ngd in cultured hippocampal neurons was examined using immunofluorescence and digital image analysis; these proteins were detected in cell bodies and distal dendrites (>75μm from the soma). In contrast, immunoreactivity for hnRNP A1 was restricted to nuclei and cell bodies (Figure S1A,B). Confocal images of sectioned hippocampal material showed punctate CPEB, Gld2, PARN, and Ngd immunoreactivity within cell bodies and MAP2-positive dendrites (Figure S1C). Moreover, CPEB, Gld2, PARN, symplekin, and Ngd were detected in synaptoneurosomes isolated from mouse hippocampus (Figure S1D).

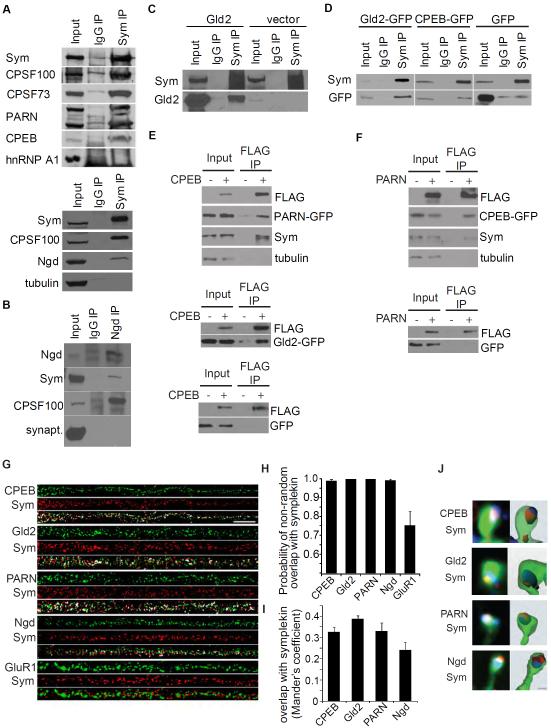

We examined the interaction of these factors in mouse brain where symplekin coimmunoprecipitated with CPSF100, CPSF73, PARN, Ngd, and CPEB (Figure1A), and Ngd coimmunoprecipitated with CPSF100 and symplekin (Figure 1B). In HEK293T and neuroblastoma cells, symplekin co-immunoprecipitated GFP-tagged CPEB and Gld2 (Figure 1C,D). Tagged CPEB co-immunoprecipitated with symplekin, tagged PARN, and tagged Gld2 (Figure 1E), and tagged PARN co-immunoprecipitated with symplekin and tagged CPEB (Figure 1F). To assess whether these components were co-localized in dendrites, cultured neurons were coimmunostained for symplekin and each other factor and 3D deconvolved images were analyzed (Figure 1G). CPEB, PARN, Gld2 and Ngd were non-randomly co-localized with symplekin (p > 0.95), while GluR1 was not (Figure 1H). The Mander’s coefficients, the fraction of total signal that is co-localized, were 0.24-0.38 demonstrating that significant levels of CPEB, PARN, Gld2, and Ngd were co-localized with symplekin in dendritic granules (Figure 1I). These proteins were also detected in dendritic spines; 3D reconstructions of phalloidin fluorescence (Figure 1J) showed that 23.1% ± 1.24% of spines contained symplekin and 80.1% ± 2.54% of symplekin-positive spines also contained CPEB, Gld2, PARN, or Ngd immunoreactivity (n=40 cells, 1196 spines). These data indicate that the cytoplasmic polyadenylation machinery forms complexes in dendrites and at synapses.

Figure 1.

Interaction and co-localization of CPEB-containing cytoplasmic complex proteins. (A,B) Mouse whole brain lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against symplekin, Ngd, or IgG control and immunoblotted as indicated. (C, D) Lysates from HEK293 cells expressing Gld2 or vector only or neuroblastoma cells expressing CPEB-GFP, Gld2-GFP, or GFP were used for co-immunoprecipitation with symplekin antibody or IgG control. (E, F) FLAG antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation of cell lysates from neuroblastoma cells expressing: (E) CPEB-FLAG or FLAG and PARN-GFP, CPEB-GFP, or GFP, and (F) PARN-FLAG or FLAG and CPEB-GFP or GFP, followed by immunoblotting for FLAG, GFP, symplekin, and tubulin. (G) Hippocampal neurons (17 DIV) were co-immunostained for symplekin (red) and CPEB, Gld2, PARN, Ngd, or GluR1 (green). The images were deconvolved and analyzed for dendritic 3D co-localization. Pixels with overlapping signals are shown in white; the scale bar is 10 μm. (H) The probability of non-random co-localization was determined for symplekin and CPEB, Gld2, PARN, Ngd or GluR1. The error bars refer to SEM. (I) Mander’s overlap coefficients were computed for each co-localized pair. The error bars refer to SEM. (J) High-magnification images and 3D reconstructions depict localization of symplekin (red) and CPEB, Gld2, PARN or Ngd (blue) in dendritic spines (green: phalloidin; scale bar is 0.5 μm). (see Figure S1)

Stimulation of Dendritic Polyadenylation by NMDA

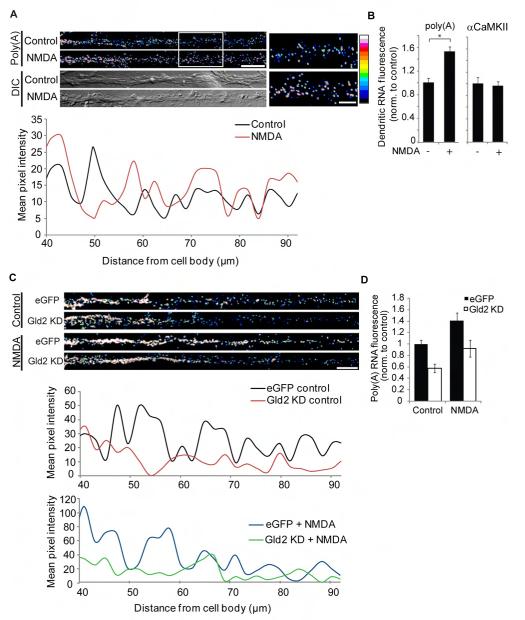

To investigate if synaptic activity induces polyadenylation in dendrites, NMDA-stimulated neurons were processed for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with oligo(dT) probes (Figure 2). Punctate poly(A) RNA was detected in the soma and dendritic arbors in a decreasing proximal-to-distal gradient (Bassell et al. 1994); oligo(dA) FISH yielded negligible signal (Figure S2A). NMDA treatment (100 nM, 30 seconds) increased dendritic oligo(dT) FISH intensity by 55% in distal regions as compared to control (Figure 2B), which was abrogated by the NMDAR antagonist APV (data not shown). NMDA did not affect dendritic αCaMKII mRNA levels (Figure 2B,S2B), indicating negligible transcript transport to distal dendrites during the brief stimulation. To determine if dendritic polyadenylation was sensitive to Gld2, neurons were transduced with lentiviruses expressing Gld2 shRNA or a control (Figure S5). Depletion of Gld2 reduced dendritic oligo(dT) FISH signals relative to controls (Figure 2C,D), indicating that this enzyme regulates dendritic polyadenylation.

Figure 2.

Gld2 regulates basal and NMDA-induced dendritic poly(A). (A) Oligo(dT) FISH was performed on 17 DIV hippocampal neurons treated with vehicle or NMDA (100 nM, 30 sec). The scale bar is 10 μm. The high magnification images show punctate poly(A) FISH signal in distal dendrites. Images were pseudocolored using the 16 color intensity map (right). Mean poly(A) pixel intensity within a 10 pixel-wide line is plotted versus distance from the soma for the representative images. (B) Control and NMDA-treated hippocampal neurons were processed for αCaMKII and poly(A) FISH, and mean dendritic FISH intensities (≥ 75 μm from the soma) were quantified (poly(A): n = 40, *P = 0.001; αCaMKII: n = 36, Control vs NMDA, P = 0.580, Student’s t-test; the error bars refer to SEM). (C) Neurons were transduced with eGFP or Gld2 shRNA lentivirus, treated with vehicle or NMDA, and processed for poly(A) FISH. Images and plots of mean pixel intensity versus distance from soma are from representative neurons. (D) Poly(A) FISH signals were quantified in distal dendrites (n = 50, two-way ANOVA, main effects: NMDA treatment, P = 0.0061, and shRNA group, P = 0.009, interaction effect: P = 0.2733; the error bars refer to SEM). (see Figure S2)

PARN is Expelled from the Polyadenylation Complex following NMDA-induced CPEB Phosphorylation

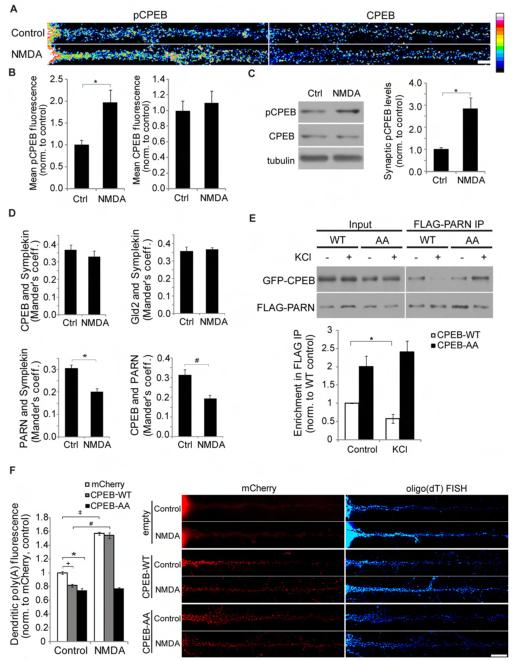

In oocytes, polyadenylation is activated by CPEB phosphorylation (Hodgman et al., 2001; Mendez et al., 2000), which induces PARN expulsion from the CPEB-containing complex (Kim and Richter 2006). NMDAR activation elicits CPEB phosphorylation in neurons (Atkins et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2002), but whether this occurs in dendrites is unknown. To assess this possibility, hippocampal neurons were treated with NMDA and immunostained for phospho- or total CPEB (Figure 3A). NMDA stimulation increased mean pCPEB immunofluorescence intensities in dendrites ≥75 μm from the soma by 90%, while total dendritic CPEB levels were not significantly affected (Figure 3B). In synaptoneurosomes from cortical neurons, NMDA treatment increased synaptic pCPEB ~2.5 fold compared to control (Figure 3C). Inhibitors of Aurora A and CaMKII, two enzymes that phosphorylate CPEB in neurons (Atkins et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2002), occluded NMDA-induced CPEB phosphorylation in dendrites and synapses (Figure S3A,B). These data suggest that NMDAR activation leads to rapid CPEB phosphorylation at synapses.

Figure 3.

NMDA receptor activation induces CPEB phosphorylation, dissociation of PARN, and dendritic mRNA polyadenylation. (A) Neurons treated with vehicle or 100 nM NMDA (30 sec) were immunostained for phosphorylated (pCPEB-T171) or total CPEB. Images were pseudocolored with the 16-color intensity map shown at right. The scale bar is 10 μm. (B) Mean fluorescence intensities were quantified in dendritic regions ≥ 75 μm from the soma (n = 45 cells, *P = 0.002, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). (C) Synaptoneurosomes from cortical neuron cultures were probed for pCPEB and CPEB; tubulin was used as a loading control. Immunoblots were quantified by densitometry (n = 6, *P = 0.003, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). (D) Hippocampal neurons treated with vehicle or 100 nM NMDA (30 sec) were co-immunostained and analyzed for 3D co-localization. The histograms display the Mander’s overlap coefficients (n = 45 cells, *P = 0.01, #P = 0.003, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). (E) Neuroblastoma cells expressing FLAG-PARN and GFP-tagged CPEB-WT or CPEB-AA were treated with vehicle or 90mM KCl (5 min). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted for GFP and FLAG. Immunoblots were quantified by densitometry; the IP values were normalized to input values (n=6; *P = 0.024, one-way ANOVA post-hoc Tukey’s test; error bars refer to SEM). (F) 12 DIV hippocampal neurons expressing mCherry, mCherry-CPEB-WT, or mCherry-CPEB-AA were treated with vehicle or 100nM NMDA (30 sec), fixed, and processed for oligo(dT) FISH. Mean oligo(dT) fluorescence intensity was quantified in distal dendritic regions (n = 35-40 cells; *P = 0.045, +P = 0.033, ‡P = 0.003, #P = 0.005; one-way ANOVA post-hoc Tukey’s test; error bars refer to SEM). (see Figure S3)

To determine whether NMDAR activation alters the composition of the dendritic polyadenylation complex, neurons were treated with NMDA, co-immunostained for complex components, and analyzed for 3D co-localization (Figure S3C). Although NMDA did not alter CPEB or Gld2 co-localization with symplekin, it reduced the co-localization of PARN with symplekin and CPEB with PARN (Figure 3D; total PARN levels were not affected, data not shown). Inhibitors of Aurora A and CaMKII blocked the NMDA-induced reduction of PARN co-localization with symplekin suggesting that CPEB phosphorylation triggers the release of PARN from dendritic CPEB-containing complexes (Figure S3D). PARN expulsion was also indicated by biochemical data (Figure 3E and S3E). Membrane depolarization of neuroblastoma cells increased CPEB phosphorylation and decreased co-immunoprecipitation of PARN with wild type (WT), but not phospho-mutant CPEB (CPEB-AA). Thus, activity-induced CPEB phosphorylation disrupts the interaction between PARN and CPEB-containing complexes in neurons.

To determine whether CPEB phosphorylation regulates dendritic polyadenylation, we evaluated oligo(dT) FISH intensity in neurons expressing CPEB-WT or CPEB-AA (Figure 3F). The expression and localization of the three proteins in dendrites were similar (data not shown). Steady-state dendritic oligo(dT) FISH intensity was reduced by both CPEB-WT (20%) and CPEB-AA (28%) compared to controls. NMDA increased dendritic oligo(dT) FISH intensity in control (56.9%) and CPEB-WT expressing (89.0%) neurons, whereas CPEB-AA expression blocked this effect. In addition, pre-treatment with Aurora A or CaMKII inhibitors occluded the NMDA-induced increase in dendritic oligo(dT) FISH intensity (Figure S3F). We infer that the dendritic mRNA polyadenylation machinery is regulated by NMDAR activity, and that CPEB phosphorylation leads to PARN extrusion from this complex resulting in polyadenylation in dendrites.

Identification of the mRNAs that are Regulated by Gld2 in Neurons

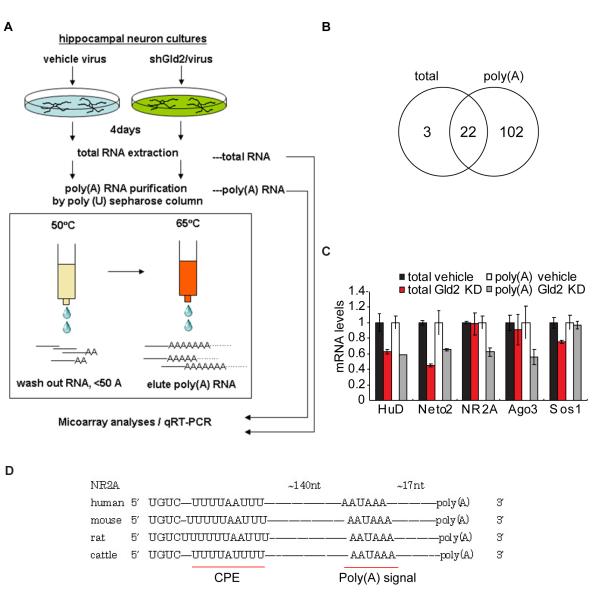

The data presented above imply that Gld2 controls dendritic polyadenylation and translation of specific mRNAs. To identify them, RNA was extracted from hippocampal neurons transduced with Gld2 shRNA-expressing or control lentivirus and applied to poly(U)-Sepharose (Figure 4A); RNAs eluting at 50°C have poly(A) tails ~50 nucleotides while 65°C eluates contain RNAs with longer poly(A) (Du and Richter, 2005; Simon et al.,1996). Both total RNA and 65°C RNA eluates were processed for microarrays. In total RNA samples, 25 mRNAs were significantly reduced by Gld2 knockdown. In the 65°C eluates, 124 mRNAs were reduced following Gld2 depletion. These RNA sample sets largely overlapped (Figure 4B and Table S1), indicating that at least 100 different mRNAs had undergone a loss of poly(A) following Gld2 knockdown.

Figure 4.

Identification of mRNAs whose polyadenylation is controlled by Gld2. (A) Hippocampal cultures were transduced with eGFP or Gld2 shRNA-expressing lentivirus for 4 days, followed by RNA extraction. A portion of the was used for microarrays while the remainder was applied to poly(U) Sepharose, eluted at 65°C, and microarray analysis. (B) Venn diagram showing that 25 and 124 mRNAs were significantly reduced in total and poly(A) RNA fractions, respectively, upon Gld2 knockdown. Twenty-two mRNAs were detected in both samples. (C) Selected mRNAs were examined by qRT-PCR; the mRNA levels in the Gld2 knockdown samples (total and eluates from poly(U)) were normalized to vehicle levels. The error bars refer to SEM. (D) Alignment of conserved CPE sequences and polyadenylation signals in the 3′UTR of NR2A mRNA from different species. (see Figure S4)

Twenty-seven of these mRNAs have been implicated in synaptic plasticity and/or nervous system disorders; five were selected and the microarray data were validated by qRTPCR (Figure 4C). HuD (RNA binding protein) and Neto2 (kainate receptor modulator) mRNAs were reduced in the total and poly(A) RNA fractions following Gld2 knockdown, suggesting that they became unstable or their transcription was indirectly reduced upon Gld2 depletion. NR2A (NMDAR subunit) and Ago3 (Piwi protein) mRNAs were reduced only in the poly(A) RNA fraction, suggesting that their poly(A) tails were shortened by Gld2 depletion without affecting stability. Sos1 (Ras/Erk2 guanine nucleotide exchange factor) was significantly decreased only in the total RNA fraction. Although Gld2 probably influences neuron function by regulating many mRNAs, we focused on NR2A because its 3′ UTR contains conserved CPEs (Figure 4D).

NR2A mRNA is Localized to Dendrites and Regulated by Gld2 and Ngd

Examination of neurons by FISH revealed that NR2A mRNA is partially dendritic. The ratio of dendrite to soma FISH fluorescence for NR2A mRNA was similar to αCaMKII and PSD95 mRNAs, which are dendritic, and significantly greater than that of β-tubulin, a nondendritic mRNA (Figure S4; Muddashetty et al., 2007).

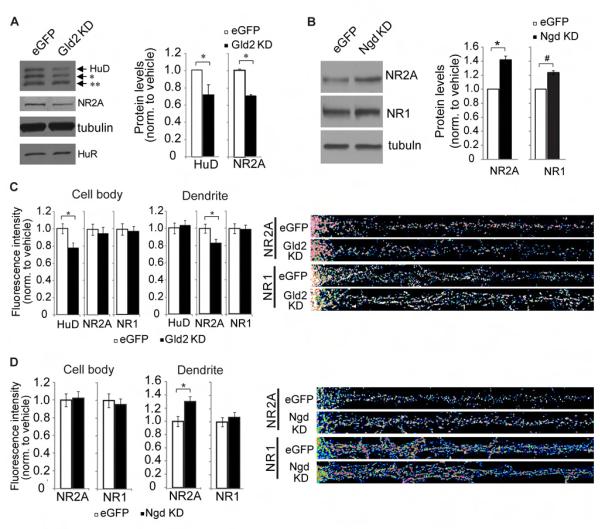

Upon Gld2 knockdown in hippocampal neurons, HuD and NR2A protein levels decreased by 27% and 31%, respectively (neither tubulin nor HuR was significantly affected) (Figure 5A). Conversely, depletion of Ngd, a translational repressor that inhibits eIF4F assembly (Jung et al. 2006), resulted in a 40% increase in NR2A (HuD was not measured; note that although tubulin was unaffected, the NMDAR subunit NR1 increased by ~20%) (Figure 5B). To determine if this regulation occurs in dendrites, we performed immunocytochemistry for NR2A following depletion of Gld2 or Ngd. While NR1 signal was not significantly altered, depletion of Gld2 reduced dendritic NR2A by ~20% and depletion of Ngd increased it by 30% (Figure 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Bidirectional control of NR2A protein expression by Gld2 and Ngd. (A) Cultured neurons were transduced with control (eGFP) or Gld2 shRNA lentivirus for 7 days, followed by western blotting for HuD and NR2A . α-tubulin and HuR served as negative controls (n = 4; *P < 0.05, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). The asterisks indicate cross-reacting HuB and HuC. (B) Neurons transduced with eGFP or Ngd shRNA lentivirus were probed for NR2A, NR1, and tubulin by western blot (n = 3, *P = 0.015, #P = 0.023, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). (C, D) Hippocampal neurons were treated with eGFP, Gld2 shRNA, or Ngd shRNA lentivirus at 11 DIV and immunostained for HuD, NR2A or NR1 4 days later. Somatic and dendritic fluorescence intensities were quantified (*P < 0.05, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). (see Figure S5)

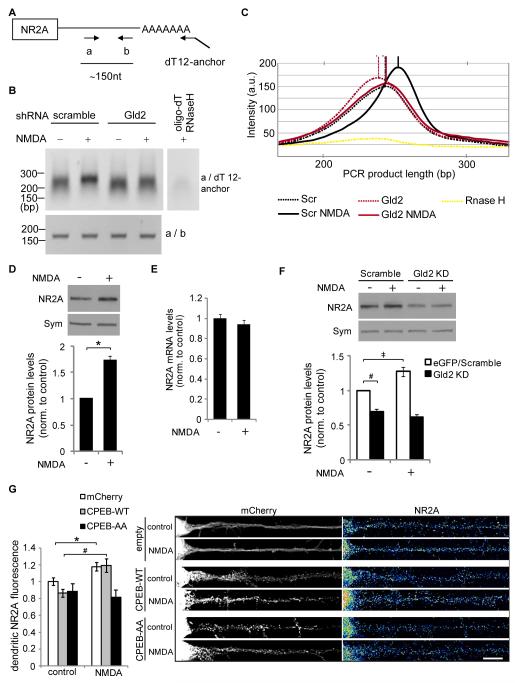

Given that Gld2 and Ngd bidirectionally regulated NR2A expression, we investigated whether the cytoplasmic polyadenylation machinery and NMDAR activation directly regulated NR2A mRNA using a PCR-based poly(A) test (PAT, Figure 6A). NMDA stimulation increased the population of NR2A mRNA with a long (~150 nt) poly(A) tail, while Gld2 depletion reduced this NMDA-stimulated polyadenylation (Figure 6B,C). NMDA treatment (100nM for 20 min) increased NR2A protein by 73% while NR2A mRNA was not significantly altered (Figure 6D,E). Gld2 depletion blocked the NMDA-induced increase in NR2A (Figure 6F), suggesting that Gld2 mediates NMDA-induced NR2A mRNA translation. To determine if CPEB phosphorylation regulated dendritic NR2A protein levels, we evaluated dendritic NR2A immunofluorescence in neurons expressing CPEB-WT or CPEB-AA. NMDA treatment significantly increased dendritic NR2A protein in control transfected cells (17.9%) and CPEB-WT-expressing cells (38.0%), whereas CPEB-AA expression blocked this effect (Figure 6G). These results demonstrate that the cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex bidirectionally regulates NR2A mRNA polyadenylation and translation upon NMDAR activation, and suggest that such regulation could have important consequences for hippocampal synaptic plasticity.

Figure 6.

NMDA induces Gld2-dependent polyadenylation and translation of NR2A mRNA. (A) A PAT assay used primers a and dT-anchor; primers a and b served as an internal control. (B) Cultured hippocampal neurons were transduced by shRNA-expressing lentivirus for 4 days and stimulated with 100nM NMDA for 20 min, followed by RNA extraction and RT-PCR with primers for PAT assay (top) and the internal control (bottom). RT-PCR of RNA digested by RNase H in the presence of oligo(dT) was used to validate amplification of the poly(A) tail. (C) Images of the PAT assay in (B) were quantified by densitometry; the band intensities were plotted versus PCR product length (base pairs) and the peak intensity is identified by a vertical line. (D) Western blotting and (E) qRT-PCR were performed on vehicle- and NMDA-treated neuron cultures; γ-actin mRNA was used for normalization of NR2A mRNA (n = 4; paired t-test, P = 0.222) and symplekin served as a loading control (n = 4; paired t-test, *P = 0.01; error bars refer to SEM). (F) Hippocampal cultures were transduced and treated as in (B), followed by western analysis (n = 3; ANOVA post-hoc Tukey’s, ‡P = 0.008, #P = 0.002, Gld2 KD groups: P = 0.576; error bars refer to SEM). (G) Neurons were transfected with mCherry, CPEB-WT-mCherry, or CPEB-AA-mCherry and treated with NMDA as in (B), followed by immunofluorescence for NR2A and quantification of dendritic NR2A fluorescence (n = 45 - 53 neurons, one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey’s tests, * P = 0.022, # P = 0.002, CPEB-AA groups: P = 0.461; error bars refer to SEM).

Chemical-Induced LTP in Cultured Neurons Elicits CPEB Phosphorylation and mRNA Polyadenylation

The data presented thus far indicate that NMDAR signaling is required for CPEB phosphorylation and mRNA polyadenylation in neurons even though the NMDA concentration used (100nM) is below that required to elicit plasticity. To determine whether plasticity-inducing stimulation activates the CPEB complex and stimulates NR2A mRNA translation, we treated cultured hippocampal neurons with glycine (200 μM, 3 min), which elicits NMDAR-dependent LTP (Lu et al. 2001). Glycine induced GluR1 S831 and S845 phosphorylation (Figure S6A), indicating the induction of LTP. This treatment also induced CPEB phosphorylation (Fig S6B) and polyadenylation in distal dendrites (Figure S6C). Furthermore, glycine stimulated NR2A mRNA polyadenylation when examined by PAT assay, which was attenuated by Gld2 depletion; RNA levels were unaffected (Figure S6D). Finally, glycine stimulated NR2A protein expression but not when Gld2 was depleted (Figure S6E). These data indicate that an LTP-induced signaling activates the cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex and stimulates NR2A production.

Gld2 Enhances and Ngd Inhibits LTP at Hippocampal Synapses

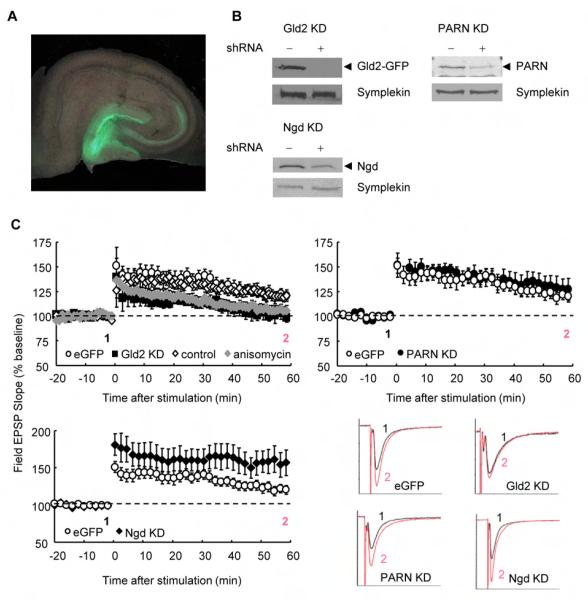

CPEB knockout mice exhibit a deficit in theta burst stimulation (TBS)-induced LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses (Alarcon et al., 2004; Zearfoss et al., 2008), which is consistent with the glycine-induced LTP in cultured neurons because both are probably regulated by NMDAR-dependent mechanisms (Musleh et al., 1999). Furthermore, L-LTP-inducing tetanus leads to NMDAR-dependent CPEB phosphorylation in hippocampal CA1 region (Atkins et al., 2005), suggesting that activation of the cytoplasmic polyadenylation apparatus can mediate synaptic plasticity in vivo. However, the findings described thus far do not address a causal relationship between polyadenylation and synaptic function. To do so, we delivered lentiviruses expressing shRNAs against Gld2, PARN, or Ngd into the hippocampus of living rats (Miyawaki et al., 2009) and examined the impact on synaptic plasticity in acute hippocampal slices. Transduction was observed throughout the hippocampus two weeks after injection and was particularly striking in granule cells of the dentate gyrus (DG), as assessed by GFP fluorescence (Figure 7A). High magnification indicated that ~50% of the granule cells were transduced (data not shown). The DG cells exhibited strong shRNA-mediated knockdown, as analyzed by RT-PCR (Figure S7A) and western blots (Figure 7B). PARN and Ngd levels were reduced by ~50%, and shRNA to Gld2 reduced Gld2-GFP from a co-injected lentivirus by >95%.

Figure 7.

shRNA-mediated knockdown of Gld2 and Ngd impair LTP at medial perforant pathway to DG granule cell synapses. (A) Hippocampal slices were prepared two weeks after stereotactic injection of lentiviruses expressing eGFP alone or with shRNAs for Gld2, PARN, or Ngd into the hippocampus of live rats. GFP expression was most prominent in the DG. (B) After transduction, the GFP-positive DG was dissected and examined for extent of knockdown by western blotting. Gld2 knockdown was determined by co-injection of lentivirus expressing Gld2-eGFP. Symplekin served as a loading control. (C) TBS-induced LTP at DG granule cell synapses was elicited in acute slices and measured 55-60 min after tetanus. Slices treated with vehicle (n = 10) or anisomycin (n = 8) were compared (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test; error bars refer to SEM). shRNA-injected groups were compared to lentivirus-eGFP injected control animals (eGFP: n = 11; Gld2 KD: n = 6, P < 0.05; PARN KD: n = 7, P > 0.05; Ngd: n = 10, P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). One slice per animal was used. Data for lentivirus-injected controls were identical in all graphs. Representative sample traces are shown on the lower right. (Figure S6)

We determined whether TBS-induced LTP in the DG was protein synthesis-dependent in hippocampal slices. TBS was evoked in medial perforant path to DG granule cell synapses in slices from uninjected 5-week-old rats (Figure 7C). TBS induced robust LTP in control slices (120% of baseline at 55-60 min post-TBS). The protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin did not alter short term plasticity (~130% of baseline at 5 min), but greatly diminished potentiation assessed at 15 and 55-60 min post-TBS (5% increase at 55-60 min), relative to that of control slices. These data indicate that TBS-induced LTP at DG granule cell synapses is protein synthesis-dependent in acute hippocampal slices.

To examine the impact of the polyadenylation machinery on protein synthesis-dependent hippocampal LTP, we recorded TBS-evoked LTP in slices from Gld2, PARN, and Ngd knockdown animals (Figure 7C). Slices from lentivirus-injected control animals showed a 22% increase in fEPSP slope at 55-60 min, which was similar to uninjected controls. Gld2 shRNA reduced LTP (101% at 55-60 min), which was similar to that produced by anisomycin. A second shRNA against Gld2 also reduced LTP (Figure S7B). These data suggest that Gld2-dependent polyadenylation is required for the protein synthesis-dependent phase of TBS-evoked LTP at DG granule cell synapses. Although PARN knockdown did not alter LTP, Ngd knockdown increased LTP to 156% at 55-60 min. These data demonstrate that CPEB-associated factors modify protein synthesis-dependent synaptic plasticity at hippocampal synapses in opposite directions: Gld2, which stimulates translation, enhances LTP, while Ngd, which inhibits translation, attenuates LTP.

We assessed basal synaptic transmission (fEPSP input/output relation) and presynaptic function (paired pulse relation) in slices from lentivirus-injected rats (Figure S7C,D). While Gld2 knockdown did not affect either measure, depletion of PARN or Ngd increased the paired pulse ratio, suggesting that they might also affect presynaptic release probability; this could also modulate the LTP enhancement in the Ngd depletion experiment.

Because dendritic spine number and shape impact synaptic efficacy (Kirov and Harris 1999), we examined spine density and morphology in hippocampal neurons following Gld2, PARN, and Ngd depletion (Figure S7E,F). Knockdown of each increased dendritic spine density (Figure S7G), indicating that the cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex regulates synapse formation. Furthermore, Gld2 knockdown increased the proportion of immature (stubby-shaped) spines and decreased the incidence of mature (mushroom-shaped) spines, which is indicative of reduced synaptic efficacy. Conversely, Ngd depletion reduced the proportion of immature (thin-shaped) spines and increased the number of mature spines suggesting that Ngd knockdown increased synaptic efficacy (Figure S7H). These data demonstrate that Gld2 and Ngd bidirectionally regulate spine morphology and synaptic strength.

Discussion

We propose a model for the bidirectional control of local translation that could underlie synaptic plasticity. NR2A mRNA, which contains CPEs in its 3′ UTR, has a short poly(A) tail and is translated inefficiently. The RNA is bound by CPEB, which in turn is associated with PARN, Gld2, symplekin, and Ngd; because Ngd is also bound to eIF4E, the cap binding factor, translation is blocked at initiation. TBS-evoked NMDAR activation promotes phosphorylation of CPEB and expulsion of PARN from the RNP complex. Gld2 then catalyzes poly(A) addition to NR2A mRNA, which we surmise leads to the displacement of Ngd from eIF4E, the binding of eIF4G to eIF4E, and translational enhancement of NR2A mRNA. Although we show that CPEB phosphorylation and Gld2-dependent polyadenylation occurs in dendrites, it is also possible that somatic mRNA regulation by the CPEB complex contributes to the observed affects. Nonetheless, the fact that dendritic translation mediates synaptic plasticity (Huber et al., 2000; Kang and Schuman, 1996) coupled with our data showing that CPEB, Gld2, and Ngd regulate dendritic mRNA polyadenylation and translation as well as synaptic efficacy suggests that local polyadenylation-induced translation could directly influence synaptic plasticity.

Gld2 is an important regulator of neuronal function as it enhances dendritic spine maturation, LTP, dendritic polyadenylation, and dendritic NR2A levels. In support of this assertion, a dominant negative Gld2 mutant inhibits long-term memory in Drosophila (Kwak et al., 2008). We have identified 102 mRNAs whose poly(A) tail size is reduced following depletion of Gld2, including several encoding plasticity-related proteins. For example, HuD is involved in dendritic morphogenesis and memory formation (Bolognani et al., 2007), Sos1 links glutamate receptors to the Erk signaling pathway (Tian et al., 2004), and Neto2 affects kainate receptor function (Zhang et al., 2009). Gld2 also affects the stability of miR122 by regulating its monoadenylation in liver and primary fibroblasts (Katoh et al., 2009; Burns et al., 2011). Although there is very little miR122 in the brain, it is possible that Gld2 regulates the stability of other neuronal miRNAs, which could influence synaptic function.

We focused on NR2A as a target of Gld2 because NMDARs are implicated in synaptogenesis, synaptic plasticity and cognitive functions such as learning and memory. NMDARs are tetramers consisting of two NR1 subunits and two NR2 subunits, and NMDARs in the hippocampus are primarily NR1/NR2A, NR1/NR2B, or NR1/NR2A/NR2B hetero-trimers (Gray et al., 2011). NR2A and NR2B differentially affect NMDAR channel properties, protein interactions, and subcellular localization, thus NR2A and NR2B subunit expression critically regulate synaptic function (Bellone and Nicoll, 2007; Lau and Zukin, 2007). LTP at hippocampal mossy fiber-CA3 synapses is expressed by insertion of NMDA receptors, thus NR2A-containing NMDARs can play a role in LTP expression as well as induction (Kwon and Castillo, 2008; Rebola et al., 2008). It is unknown whether local protein synthesis is involved in this process, but it is conceivable that a local pool of newly synthesized NR2A could contribute to activity-dependent NMDAR insertion. Indeed, LTP stimulation leads to NR2A production in the DG (Williams et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2002). It is also possible that NR2A synthesis might be required to enhance future synaptic responses. In any case, we envision that Gld2 helps maintain NR2A homeostasis in synapto-dendrites, and thus may act as a rheostat to provide the proper level and/or stoichiometry of NMDAR subunits. Even so, other Gld2 target mRNAs may also contribute to synaptic efficacy.

Other neuronal mRNAs polyadenylated in the cytoplasm such as those encoding α CaMKII (Wu et al., 1998), AMPA receptor binding protein (Du and Richter, 2005), and tissue plasminogen activator (Shin et al., 2004) were not detected as having diminished poly(A) tail length following Gld2 knockdown. These results might indicate that a second poly(A) polymerase also functions in the cytoplasm of neurons; possible candidates include canonical poly(A) polymerase (Huang et al., 2002) or Gld4 (Burns et al., 2011). The extent to which CPEB mediates Gld2 function is also unclear. Gld2 has no RNA binding domain and must be tethered to RNA via an RNA binding protein. CPEB is one protein that anchors Gld2 to RNA, but Gld2 also interacts with the RNA binding proteins that may increase the repertoire of mRNAs that are regulated by polyadenylation (Kim et al., 2009). In the mammalian brain, one could envision how Gld2 might interact with different RNA binding proteins, and thus, activate different mRNAs in a synaptic stimulation-dependent manner.

NMDA treatment of neurons causes CPEB phosphorylation, PARN expulsion from the CPEB-containing RNP complex, and mRNA polyadenylation. These observations suggest that PARN would play a critical role in dendritic translation and possibly synapse function. However, PARN knockdown had only a modest affect on dendritic spine morphology in cultured neurons and no significant effect on TBS-evoked LTP in the DG. It is possible that the PARN knockdown of ~50% was not sufficient to alter synaptic plasticity, or the loss of PARN may not have been sufficient to overcome other negative regulators of translation in the same RNP complexes, such as Ngd. Alternatively, PARN might control the deadenylation of mRNAs when LTP is induced by different stimulation protocols, or in response to stimuli that evoke LTD.

We have shown that Gld2 and Ngd mediate protein synthesis-dependent LTP in the DG. In our paradigm, LTP was protein synthesis-dependent shortly after TBS. In cultured neurons, NMDA stimulation elicited rapid CPEB phosphorylation, PARN exclusion, and dendritic polyadenylation, perhaps signifying that CPEB-mediated polyadenylation has an important early role during synapse potentiation in the DG. Moreover, Gld2 knockdown affected basal polyadenylation in addition to activity-induced poly(A) levels, which could indicate that steady-state Gld2 activity primes some dendritic mRNAs for impending stimulation-induced translation. It is also possible that CPEB complex proteins control the threshold for eliciting L-LTP by regulating basal translation as eIF2 phosphorylation does (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2007).

In this report, we have defined a new molecular mechanism and identified critical factors controlling translation and synaptic plasticity in mammalian neurons. Translational control of any particular mRNA is often a complex process involving factors that influence different steps in translation. Indeed, NR2A translation is also regulated in part by an FMRP-microRNA pathway (Edbauer et al., 2010). FMRP, like CPEB, regulates the translation of particular mRNAs in a stimulus-specific manner; it responds to mGluR-mediated signaling to regulate translation in dendrites (Bassell and Warren, 2008). If one presumes that unique as well as shared mRNAs are translated in response to, for example, NMDAR- and mGluR-mediated signaling, then it becomes evident how combinations of newly synthesized proteins could impart characteristics to synapses that are exclusive to each signaling event.

Experimental Procedures

Neuron Culture and Drug Treatment

Rat hippocampal neuron cultures were prepared as described (Goslin and Banker 1998; Huang and Richter 2007). Neurons were treated with 100nM NMDA (Tocris Bioscience) or vehicle for 30 seconds then fixed or lysed. Inhibitors were applied for 30 min prior to NMDA as follows: 100nM ZM447473 (Tocris Bioscience), 10μM KN-93 (Millipore), and 50μM APV (Tocris Bioscience).

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Mouse brains, HEK293T cells, and Neuro2A cells were lysed and immunoprecipitations were performed as described (Kim and Richter 2006). Two percent of each lysate was used as the input standard.

Immunofluorescence and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Mouse brains from male C57BL/6 mice postnatal day 21 (P21) and cultured hippocampal neurons were processed for immunofluorescence or FISH as described (Muddashetty et al., 2007; Swanger et al., 2011). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for antibody information, probe sequences, and image analysis details.

Stereotactic Injection of Lentiviruses

Male P21-24 Sprague-Dawley rats were injected with shRNA-expressing lentiviruses as described (Miyawaki et al. 2009). Lentiviral solution was injected into the right hippocampus (3 mm posterior to bregma, 2 mm lateral to midline, 4.1 mm below the skull surface) at a rate of 0.2μl/min. After the injection, the rats recovered for 13-17 days and exhibited normal grooming and exploring behaviors.

Electrophysiology

Acute hippocampal slices (400μm) were prepared from lentivirus-injected or uninjected rats (P35-38) as described (Yang et al. 2009). fEPSPs were evoked by stimulation of the medial perforant path and recorded in the middle third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. Baseline presynaptic stimulation was delivered every 30 s for at least 30 min with a stimulation strength that gave 25-40% of the maximal fEPSP slope. After a minimum of 20 min of stable baseline, TBS was induced by 4 series of 5 trains of 10 stimuli at 200 Hz with 200 ms between trains and 30 s between series. The average of fEPSP slopes in the 20 min baseline was used to quantify the magnitude of LTP measured at 55-60 min post-TBS. Input/output relation and paired-pulse relation were measured as described (Yang et al. 2009). The data were collected and analyzed by IgorPro and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test with significance set at the p< 0.05.

Selection of Polyadenylated RNA, Microarray, and qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from the cultured neurons with TRIzol. Polyadenylated RNA was fractionated on poly(U) Sepharose followed by thermal elution (Du and Richter 2005; Simon et al. 1996). The Sepharose was washed at 50°C and the RNA eluted at 65°C. Total RNA and RNA from 65°C eluates were phenol extracted and purified by an RNeasy MinElute purification kit (Qiagen). RNAs were used as templates to synthesize biotin-labeled cRNAs that were hybridized to the Affymetrix Rat Gene 1.0 ST Array. cRNA synthesis and hybridization were carried out according to Ambion’s and Affymetrix’s instructions, respectively. To validate the microarray data, qRT-PCR was performed using Fermentas SYBR Green qPCR Master mix. All experiments were performed in biologic replicates.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CPEB and the cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex are regulated by synaptic activity

Synaptic stimulation induces polyadenylation in dendrites

Two CPEB partners, Gld2 and Neuroguidin, enhance and repress synaptic plasticity

Gld2 controls the polyadenylation of >100 mRNAs in neurons including NR2A and HuD

Acknowledgments

We thank the UMASS Genomics and Bioinformatics Core for help with microarray analysis, Fabrizio Pontarelli for assistance with stereotactic injections, Yuncen A. He for assistance with image analysis, and Kenny Futai for comments on the manuscript. TU was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the FRAXA Foundation. SAS was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the NIH F31NS063668, T32GM0860512 and T32NS007480, and the Epilepsy Foundation and Lennox & Lombroso Trust Fund. This work was supported by NIH grants GM46779, HD37267, and AG30323 (to JDR) and MH085617 (to GJB) and a NARSAD Investigator Award (GJB). Core support at UMass Medical School from the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (P30 DK32520) and the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (P30 HD04147) and at Emory University from the NINDS Microscopy Core (P30NS055077) is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession Numbers The microarray data from the Gld2 depletion experiments in neurons are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE37695.

Supplemental information is available for this article.

References

- Alarcon JM, Hodgman R, Theis M, Huang YS, Kandel ER, Richter JD. Selective modulation of some forms of Schaffer collateral-CA1 synaptic plasticity in mice with a disruption of the CPEB-1 gene. Learn Mem. 2004;11:318–327. doi: 10.1101/lm.72704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins CM, Nozaki N, Shigeri Y, Soderling TR. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein-dependent protein synthesis is regulated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5193–5201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins CM, Davare MA, Oh MC, Derkach V, Soderling TR. Bidirectional regulation of cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein phosphorylation by Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and protein phosphatase I during hippocampal long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5604–5610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5051-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard DC, Ryan K, Manley JL, Richter JD. Symplekin and xGLD-2 are required for CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Cell. 2004;119:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Singer RH, Kosik KS. Association of poly(A) mRNA with microtubules in cultured neurons. Neuron. 1994;12:571–582. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellone C, Nicoll RA. Rapid bidirectional switching of synaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2007;55:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Sweeney J, Zearfoss NR, Richter JD. Reduced extinction of hippocampal-dependent memories in CPEB knockout mice. Learn. Mem. 2006;13:4–7. doi: 10.1101/lm.73706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse F, Ephrussi A. Translational control of localized mRNAs: restricting protein synthesis in space and time. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:971–980. doi: 10.1038/nrm2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognani F, Qiu S, Tanner DC, Paik J, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Weber EJ. Associative and spatial learning and memory deficits in transgenic mice overexpressing the RNA-binding protein HuD. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2007;87:635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DM, d’Ambrogio A, Nottrott S, Richter JD. CPEB and two poly(A) polymerases control miR-122 stability and p53 mRNA translation. Nature. 2011;473:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature09908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Stern E, Gamache K, Colina R, Cuello C, Sossin W, Kaufman R, Pelletier J, Rosenblum K, et al. eIF2alpha phosphorylation bidirectionally regulates the switch from short- to long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2007;129:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Richter JD. Activity-dependent polyadenylation in neurons. RNA. 2005;11:1340–1347. doi: 10.1261/rna.2870505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbauer D, Neilson JR, Foster KA, Wang CF, Seeburg DP, Batterton MN, Tada T, Dolan BM, Sharp PA, Sheng M. Regulation of synaptic structure and function by FMRP-associated microRNAs miR-125b and miR-132. Neuron. 2010;65:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Krug UM, Reymann KG, Matthies H. Anisomycin, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, blocks late-phases of LTP phenomena in the hippocampal CA1 region in vitro. Brain Res. 1988;452:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslin K, Banker G. Rat hippocampal neurons in low-density culture. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing nerve cells. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 1998. pp. 251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Shi Y, Usui H, During MJ, Sakimura K, Nicoll RA. Distinct modes of AMPA receptor suppression at developing synapses by GluN2A and GluN2B: single-cell NMDA receptor subunit deletion in vivo. Neuron. 2011;71:1085–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman I, Ivshina M, Marin V, Kennedy NJ, Davis RJ, Richter JD. Control of cellular senescence by CPEB. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2701–2712. doi: 10.1101/gad.1438906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgman R, Tay J, Mendez R, Richter JD. CPEB phosphorylation and cytoplasmic polyadenylation are catalyzed by the kinase IAK1/Eg2 in maturing mouse oocytes. Development. 2001;128:2815–2822. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YS, Jung MY, Sarkissian M, Richter JD. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor signaling results in Aurora kinase-catalyzed CPEB phosphorylation and alpha CaMKII mRNA polyadenylation at synapses. EMBO J. 2002;21:2139–2148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YS, Richter JD. Analysis of mRNA translation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Meth. Enzymol. 2007;431:143–162. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Kayser MS, Bear MF. Role for rapid dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Science. 2000;288:1254–1257. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MY, Lorenz L, Richter JD. Translational control by neuroguidin, a eukaryotic initiation factor 4E and CPEB binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:4277–4287. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02470-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294:1030–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Schuman EM. A requirement for local protein synthesis in neurotrophin-induced hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 1996;273:1402–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T, Sakaguchi Y, Miyauchi K, Suzuki T, Kashiwabara S, Baba T, Suzuki T. Selective stabilization of mammalian microRNAs by 3′ adenylation mediated by the cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD-2. Genes Dev. 2009;23:433–438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1761509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Richter JD. Opposing polymerase-deadenylase activities regulate cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KW, Nykamp K, Suh N, Bachorik JL, Wang L, Kimble J. Antagonism between GLD-2 binding partners controls gamete sex. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirov SA, Harris KM. Dendrites are more spiny on mature hippocampal neurons when synapses are inactivated. Nature Neurosci. 1999;2:878–883. doi: 10.1038/13178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug M, Lössner B, Ott T. Anisomycin blocks the late phase of long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats. Brain Res. Bull. 1984;13:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JE, Drier E, Barbee SA, Ramaswami M, Yin JC, Wickens M. GLD2 poly(A) polymerase is required for long-term memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14644–14649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803185105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HB, Castillo PE. Role of glutamate autoreceptors at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2008;60:1082–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CG, Zukin RS. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CL, Evans V, Shen S, Xing Y, Richter JD. The nuclear experience of CPEB: implications for RNA processing and translational control. RNA. 2010;16:338–348. doi: 10.1261/rna.1779810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu WY, Man HY, Ju W, Trimble WS, McDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2001;29:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy M, Cao G, Llopis PM, Kundel M, Jones K, Hofler C, Shin C, Wells DG. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1-mediated mRNA translation in Purkinje neurons is required for cerebellar long-term depression and motor coordination. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6400–6411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5211-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, Hake LE, Andresson T, Littlepage LE, Ruderman JV, Richter JD. Phosphorylation of CPE binding factor by Eg2 regulates translation of c-mos mRNA. Nature. 2000;404:302–307. doi: 10.1038/35005126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki T, Ofengeim D, Noh KM, Latuszek-Barrantes A, Hemmings BA, Follenzi A, Zukin RS. The endogenous inhibitor of Akt, CTMP, is critical to ischemia-induced neuronal death. Nature Neurosci. 2009;12:618–626. doi: 10.1038/nn.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muddashetty RS, Kelic S, Gross C, Xu M, Bassell GJ. Dysregulated metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent translation of AMPA receptor and postsynaptic density-95 mRNAs at synapses in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:5338–5348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0937-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musleh W, Bi X, Tocco G, Yaqhoubi S, Baudry M. Glycine-induced long-term potentiation is associated with structural and functional modifications of alfa-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9451–9456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon MM, Choi SH, Jamieson CA, Geschwind DH, Martin KC. Identification of process-localized mRNAs from cultured rodent hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:13390–13399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebola N, Lujan R, Cunha RA, Mulle C. Adenosine A2A receptors are essential for long-term potentiation of NMDA-EPSCs at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2008;57:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD. CPEB: a life in translation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD, Klann E. Making synaptic plasticity and memory last: mechanisms of translational regulation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1735809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schratt G. microRNAs at the synapse. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:842–849. doi: 10.1038/nrn2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin C, Kundel M, Wells DG. Rapid, activity-induced increase in tissue plasminogen activator is mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent mRNA translation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9425–9433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2457-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Wu L, Richter JD. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation of activin receptor mRNA and the control of pattern formation in Xenopus development. Dev. Biol. 1996;179:239–250. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins-Boaz B, Cao Q, de Moor CH, Mendez R, Richter JD. Maskin is a CPEB-associated factor that transiently interacts with elF-4E. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Levy WB. Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 1982;2:284–291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00284.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Schuman EM. Dendritic protein synthesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Cell. 2006;127:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanger SA, Bassell GJ, Gross C. High-resolution fluorescence in situ hybridization to detect mRNAs in neuronal compartments in vitro and in vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;714:103–123. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-005-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Gotoh T, Tsuji K, Lo EH, Huang S, Feig LA. Developmentally regulated role for Ras-GRFs in coupling NMDA glutamate receptors to Ras, Erk and CREB. EMBO J. 2004;23:1567–1575. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Song D, Berger TW. Contribution of NMDA receptor channels to the expression of LTP in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 2002;12:680–688. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Mason-Parker SE, Abraham WC, Tate WP. Biphasic changes in the levels of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2 subunits correlate with the induction and persistence of long-term potentiation. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;60:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Wells D, Tay J, Mendis D, Abbott MA, Barnitt A, Quinlan E, Heynen A, Fallon JR, Richter JD. CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation and the regulation of experience-dependent translation of alpha-CaMKII mRNA at synapses. Neuron. 1998;21:1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Takeuchi K, Rodenas-Ruano A, Takayasu Y, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Developmental switch in requirement for PKA RIIbeta in NMDA-receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity at Schaffer collateral to CA1 pyramidal cell synapses. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zearfoss NR, Alarcon JM, Trifilieff P, Kandel E, Richter JD. A molecular circuit composed of CPEB-1 and c-Jun controls growth hormone-mediated synaptic plasticity in the mouse hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8502–8509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1756-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, St-Gelais F, Grabner CP, Trinidad JC, Sumioka A, Morimoto-Tomita M, Kim KS, Straub C, Burlingame AL, Howe JR, et al. A transmembrane accessory subunit that modulates kainate-type glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2009;61:385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.