Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (BN) are rare, but eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS) are relatively common among female participants. Our objective was to evaluate whether BN and subtypes of EDNOS are predictive of developing adverse outcomes.

METHODS:

This study comprised a prospective analysis of 8594 female participants from the ongoing Growing Up Today Study. Questionnaires were sent annually from 1996 through 2001, then biennially through 2007 and 2008. Participants who were 9 to 15 years of age in 1996 and completed at least 2 consecutive questionnaires between 1996 and 2008 were included in the analyses. Participants were classified as having BN (≥weekly binge eating and purging), binge eating disorder (BED; ≥weekly binge eating, infrequent purging), purging disorder (PD; ≥weekly purging, infrequent binge eating), other EDNOS (binge eating and/or purging monthly), or nondisordered.

RESULTS:

BN affected ∼1% of adolescent girls; 2% to 3% had PD and another 2% to 3% had BED. Girls with BED were almost twice as likely as their nondisordered peers to become overweight or obese (odds ratio [OR]: 1.9 [95% confidence interval: 1.0–3.5]) or develop high depressive symptoms (OR: 2.3 [95% confidence interval: 1.0–5.0]). Female participants with PD had a significantly increased risk of starting to use drugs (OR: 1.7) and starting to binge drink frequently (OR: 1.8).

CONCLUSIONS:

PD and BED are common and predict a range of adverse outcomes. Primary care clinicians should be made aware of these disorders, which may be underrepresented in eating disorder clinic samples. Efforts to prevent eating disorders should focus on cases of subthreshold severity.

KEY WORDS: adolescents, eating disorders, epidemiology, obesity, substance use

What’s Known on This Subject:

Eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) is the most common eating disorder diagnosis. Binge eating disorder, 1 type of EDNOS, is associated with obesity among adults. Little is known about the health outcomes associated with other types of EDNOS.

What This Study Adds:

This is the first study to evaluate the prospective association of full and subthreshold bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, purging disorder, and other EDNOSs with specific mental and physical health outcomes.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) is widely used to classify eating disorders, but inadequacies of the classification have been identified.1–5 One of the biggest problems is that the majority of eating-disordered individuals meet some, but not all, of the criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa (BN) and thus are classified as having an eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS).4,6–9 Although EDNOS is the most common eating disorder diagnosis in both clinical and research settings, it is not usually included in estimates of eating disorders,10,11 thus resulting in a deceptively low prevalence of eating disorders.10–13 Relatively few studies report on the prevalence of binge eating disorder (BED), 1 of the subgroups within EDNOS.11–14 Swanson et al11 reported on the prevalence of full and subthreshold anorexia nervosa, BN, and BED, but purging disorder (PD), which is another EDNOS subtype, was not assessed. Thus, it is unclear how common eating disorders are in the general population.

The DSM-IV is currently being revised, and the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) plans to change the bulimic behavior cutoff required for a diagnosis of BN and BED from at least twice per week to once per week.15 The change reflects the findings of several studies that female participants who binge and purge fewer than twice a week exhibit high levels of comorbid disorders16 and functional impairment.17 The revision in the diagnostic criteria will reduce the numbers of individuals classified as having EDNOS, but its prevalence will remain high.18,19

At present, it seems that the DSM-5 will recognize 3 eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, BN, and BED, which was formerly part of EDNOS. Thus, individuals who binge eat and purge frequently will be considered to have an eating disorder (BN), as will those who binge eat frequently but do not engage in purging (BED). However, individuals who purge frequently but do not binge eat (PD) will not be a separate group. Rather, they will be 1 of several subgroups contained in an eating disorders not elsewhere classified group (which was formerly called EDNOS) because data are lacking on the risks associated with PD.

The aim of the present investigation was to assess whether BN, BED, PD, and other EDNOS were predictive of developing adverse outcomes, including becoming overweight or obese, starting to use drugs, starting to binge drink frequently, and developing high levels of depressive symptoms. Our secondary aim was to assess how the risk of adverse outcomes varied according to frequency of binge eating and purging. We assessed these aims by using 8 follow-up assessments collected from >8500 female participants in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS) who were 9 to 15 years of age at baseline.

Methods

GUTS was established in 1996 by recruiting children of women participating in the Nurses' Health Study II; additional details about this study have been reported previously.20 By using these data, we identified mothers who had children ages 9 to 14 years. Children whose mothers gave us consent to invite them to participate were mailed an invitation letter and a questionnaire. Additional details have been reported previously.21 A total of 9039 female participants and 7843 male participants returned completed questionnaires, thereby assenting to participate in the cohort. The participants were sent questionnaires in 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007. Due to sending nonrespondents multiple e-mails with links to the online questionnaire as well as several paper questionnaires, the data collection period in the 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007 cycles spanned ∼2 years.

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the analyses presented in this article were approved by the institutional review boards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital Boston.

Sample

Participants were excluded from the analysis if they were male or did not return at least 2 contiguous assessments (eg, 1996 and 1997). Sample sizes varied by outcome. In all analyses, participants who were prevalent cases at baseline (eg, overweight in 1996) were excluded, and once a participant reported the outcome of interest, she was censored from analyses using subsequent time periods. After these exclusions, 6875 female participants remained for the analyses predicting becoming overweight or obese, 7900 remained for the analyses predicting starting to binge drink, 6047 remained for the analyses predicting starting to use drugs, and 5327 remained for the analyses predicting developing high levels of depressive symptoms.

Measures

Eating Disorder Behaviors

Eating disorder behaviors have been assessed on all questionnaires. Weight concerns were assessed by using the McKnight Risk Factor Survey (MRFS).22 Purging was assessed by asking how often in the past year did the girl make herself throw up or use laxatives to keep from gaining weight. Binge eating was assessed with a 2-part question. Participants were first asked about the frequency during the past year of eating a very large amount of food. Girls who reported overeating were directed to a follow-up question that asked whether they felt out of control during these episodes, like they could not stop eating even if they wanted. Binge eating was defined as eating a very large amount of food in a short amount of time at least monthly and feeling out of control during the eating episode. Both the binge eating and purging questions have been validated in the GUTS cohort.23 In 2001, 2003, and 2005, additional questions on binge eating were asked, including whether the participant felt bad about herself or guilty after binge eating. More than 95% of girls who reported binge eating at least weekly endorsed this item.

Three different classifications were derived. In the primary analyses, the DSM-5 cutoffs for binge eating were used. Girls who reported that they engaged in binge eating at least once per week and did not engage in purging or purged less than monthly were classified as having BED. Girls who reported at least weekly use of vomiting or laxatives to control weight and did not binge eat or binged less than monthly were classified as having PD. Girls who engaged weekly in both binge eating and purging were classified as having BN. Girls who engaged in monthly binge eating and/or purging and those who went on overeating episodes but did not experience a loss of control were classified as having EDNOS.

To examine the impact of lowering the frequency threshold from weekly to monthly use of bulimic behaviors, a second classification scheme was derived. In these analyses, girls who reported engaging in binge eating at least once per month and did not engage in purging were classified as having BED. Girls who reported at least monthly use of vomiting or laxatives to control weight and did not binge eat were classified as having PD. Girls who engaged monthly in both binge eating and purging were classified as having BN. Girls who went on overeating episodes but did not experience a loss of control were classified as having EDNOS.

Outcomes

Weight Status

BMI was calculated by using self-reported weight and height assessed on all questionnaires. Among adolescents and young adults, weight change based on serial self-reported weights has been found to underestimate weight change based on measured weights by an average of only 2.1 pounds.24 Height or BMI values detected as outliers25 were set to missing and not used in the analysis. Children and adolescents aged <18 years were classified as underweight based on the age-equivalents to the World Health Organization cutoff for grade I thinness26 and overweight or obese based on the International Obesity Task Force cutoffs.27 Participants aged ≥18 years were classified as underweight if they had a BMI <18.5 and overweight if they had a BMI between 25 and 29.9. Participants with a BMI >30 were classified as obese.

Binge Drinking

A question on binge drinking was added in 1998 and appeared on the 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, and 2007 questionnaires. Thus, incident cases were ascertained in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, and 2007. Children who reported that they ever consumed alcohol were asked a series of questions about their drinking behavior. One of those questions asked about the frequency in the past year of drinking ≥4 drinks over a few hours, which was our definition of binge drinking among female participants. Participants who reported at least 6 episodes of binge drinking in the past year were classified as frequent binge drinkers.

Drug Use

Questions on drug use were added in 1999 and also were included on the 2001, 2003, and 2007 questionnaires. Thus, incident cases were ascertained in 2001, 2003, and 2007. Participants were asked whether they had used any of the following drugs in the past year: marijuana or hashish, cocaine, crack, heroin, ecstasy, PCP, γ-hydroxybutyrate, LSD, mushrooms, ketamine, crystal methamphetamine, Rohypnol, or amphetamines. In 2007, questions were also included on use of prescription drugs without a prescription. Because of an expected strong cross-sectional association between marijuana and hashish use with overeating episodes, we did not include these drugs in our drug use outcome. Participants who reported using any of the other drugs and had never reported using any of those drugs at an earlier time period were classified as incident drug use cases.

Depressive Symptoms

In 1999, 2001, and 2003, depressive symptoms were assessed by using the 6-item validated scale of the MRFS IV.22 All responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to always. In 2007, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (10-item version)28,29 was used instead of the MRFS. Questions from the MRFS were identical or similar to questions included in the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale. Participants in the top quintile of depressive symptoms were considered cases; thus, incident cases of high levels of depressive symptoms were female participants who were in 1 of the bottom 4 quintiles of depression symptoms on 1 assessment but in the top quintile on the next assessment. Incident high depressive symptoms were assessed in 2001, 2003, and 2007.

Statistical Analysis

Because anorexia nervosa was too uncommon to include as an outcome in the statistical models, the eating disorder predictors were BN, BED, PD, and EDNOS. We modeled the log-odds of the hazard rate for 4 different outcomes: becoming overweight or obese, starting to binge drink frequently, starting to use drugs other than marijuana, and developing high levels of depressive symptoms. Predictors were lagged so that outcomes at a given time point were modeled as a function of predictors from the previous time point (ie, 2001 predictors for 2003 outcomes). The models were fit by using generalized estimating equations (GEE).30 The analyses were performed by using PROC GENMOD (SAS version 9.2 [SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC]). All analyses adjusted for age. Known predictors of the outcomes were included as covariates in the final models. These covariates varied by outcome. BMI and dieting were included in models predicting the development of overweight or obesity. Having a sibling who used drugs, having a sibling who started drinking before age 18 years, ≥1 friend who use drugs, ≥1 adult at home who drinks, and region of the country were adjusted for in the models predicting drug uses. BMI, having a sibling who started drinking before age 18 years, ≥1 friend who drinks, ≥1 adult at home who drinks, and region of the country were included in models predicting binge drinking, and BMI and level of depressive symptoms at the previous assessment were adjusted for in the models of depressive symptoms.

Results

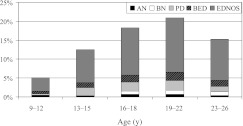

At baseline in 1996, the 8594 girls were on average 12.0 years of age (Table 1). The prevalence of eating disorders increased with age until early adulthood (Fig 1). At all ages, EDNOS was by far the most common disorder, with a prevalence ranging between 3% (9–12 years) and 15% (19–22 years). The least common disorder in all age groups was anorexia nervosa, and BN was the second most uncommon. Approximately 2% to 2.5% of girls in each adolescent and young adult age group had PD and another 2% to 2.5% had BED. Even if EDNOS were disregarded, between 4% and 6% of adolescent and young adult females had an eating disorder.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of 8594 Adolescent Female Participants at Baseline in GUTS

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 12.0 ± 1.6 |

| Weight status, % | |

| Overweight | 15.7 |

| Obese | 3.8 |

| Region, %a | |

| West | 14.2 |

| Midwest | 35.6 |

| South | 14.6 |

| Northeast | 35.4 |

| Sibling who uses drugs, %b | 6.9 |

| Sibling who drank at age <21 years, %c | 14.0 |

| Friends who uses drugs, %c | 41.4 |

| Friends who drink, %c | 43.5 |

| ≥1 adult at home who drinks, %c | 63.2 |

First assessed in 1997.

First assessed in 1999.

First assessed in 1998, or 1998 is the first year used in the analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Age-specific prevalence of eating disorders among girls in GUTS.

Between 1996 and 2007, 19.8% (n = 1360) of girls became overweight or obese, 24.9% (n = 1506) started to use drugs other than marijuana, 36.3% (n = 2868) started to binge drink frequently, and 27.4% (n = 1460) developed high levels of depressive symptoms. Approximately 22% of the girls developed ≥2 of the outcomes.

Girls with BED (35.1%) were more likely than girls with BN (18.9%), PD (24.2%), or EDNOS (25.1%) to be overweight or obese. After excluding those prevalent cases, in age-adjusted analyses, girls with BED and EDNOS were significantly more likely to become overweight or obese over the following year (Table 2). However, after further adjusting for BMI and dieting in the previous time period, the association with EDNOS was attenuated and no longer significant. When the frequency cutoff was changed from weekly (ie, full criteria cases) to monthly (ie, subthreshold and full criteria cases) use of bulimic behaviors, there was a suggestion that both BED (odds ratio [OR]: 1.35) and PD (OR: 1.49) were associated with an increased risk of becoming overweight or obese (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

ORs and 95% CIs for the Prospective Association Between Eating Disorder Subtypes and the Risk of Becoming Overweight, Starting to Use Drugs, and Starting to Binge Drinking Frequently

| Eating Disorder | Incident Overweight, 1996–2007 | Start to Use Drugs, 1999–2008 | Start Binge Drinking Frequently, 1999–2008 | Develop High Depressive Symptoms, 1999–2008 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusteda | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjustedb | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjustedc | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjustedd | |

| Nondisordered | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| PD (≥weekly) | 1.21 (0.71–2.05) | 1.00 (0.48–2.06) | 2.45 (1.60–3.74) | 1.72 (0.97–3.06) | 1.69 (1.23–2.33) | 1.84 (1.28–2.65) | 1.31 (0.75–2.28) | 1.17 (0.63–2.19) |

| BN (≥weekly) | 0.71 (0.22–2.24) | 0.89 (0.25–3.16) | 3.77 (1.92–7.42) | 3.91 (1.83–8.37) | 2.39 (1.43–4.00) | 1.73 (0.97–3.06) | 2.55 (0.81–8.01) | 0.42 (0.05–3.42) |

| BED (≥weekly) | 1.88 (1.23–2.87) | 1.90 (1.04–3.48) | 1.13 (0.71–1.81) | 0.53 (0.19–1.52) | 1.27 (0.92–1.75) | 1.07 (0.66–1.73) | 3.20 (1.97–5.21) | 2.28 (1.03–5.03) |

| EDNOS | 1.60 (1.29–1.99) | 1.20 (0.93–1.54) | 1.42 (1.16–1.75) | 1.52 (1.20–1.93) | 1.63 (1.41–1.89) | 1.64 (1.38–1.94) | 1.62 (1.28–2.04) | 1.31 (1.02–1.69) |

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, BMI, and dieting.

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, having a sibling who used drugs, having a sibling who started drinking before age 21 years, ≥1 friend who uses drugs, ≥1 adult at home who drinks, and region of the country.

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, BMI, having a sibling who started drinking before age 21 years, ≥1 friend who drinks, ≥1 adult at home who drinks, and region of the country.

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, BMI, and level of depressive symptoms at the previous assessment.

TABLE 3.

ORs and 95% CIs for the Prospective Association Between Eating Disorder Subtypes of Subthreshold or Full Criteria Severity and the Risk of Becoming Overweight, Starting to Use Drugs, and Starting to Binge Drink Frequently

| Eating Disorder | Incident Overweight, 1996–2008 | Start to Use Drugs, 1999–2008 | Start Binge Drinking Frequently, 1999–2008 | Develop High Depressive Symptoms, 1999–2008 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjusteda | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjustedb | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjustedc | Age-Adjusted | Fully Adjustedd | |

| Nondisordered | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| PD (≥monthly) | 2.08 (1.50–2.89) | 1.49 (1.00–2.21) | 2.40 (1.69–3.42) | 2.06 (1.37–3.09) | 1.89 (1.48–2.42) | 1.75 (1.34–2.27) | 1.62 (1.08–2.43) | 1.34 (0.88–2.05) |

| BN (≥monthly) | 0.95 (0.49–1.86) | 0.91 (0.45–1.88) | 3.43 (2.16–5.43) | 3.76 (2.27–6.25) | 3.24 (2.28–4.61) | 2.59 (1.76–3.81) | 2.55 (1.26–5.16) | 0.95 (0.38–2.39) |

| BED (≥monthly) | 1.94 (1.45–2.58) | 1.35 (0.98–1.87) | 1.24 (0.91–1.68) | 1.21 (0.86–1.71) | 1.48 (1.21–1.81) | 1.42 (1.13–1.79) | 2.51 (1.83–3.44) | 1.77 (1.23–2.46) |

| EDNOS (overeat without loss of control) | 1.33 (0.94–1.88) | 0.92 (0.60–1.42) | 1.20 (0.87–1.64) | 1.11 (0.79–1.58) | 1.41 (1.13–1.76) | 1.40 (1.09–1.79) | 1.42 (1.01–1.99) | 1.09 (0.75–1.57) |

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, BMI, and dieting.

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, having a sibling who used drugs, having a sibling who started drinking before age 21 years, ≥1 friend who use drugs, and region of the country.

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, BMI, having a sibling who started drinking before age 21 years, ≥1 friend who drinks, ≥1 adult at home who drinks, and region of the country.

Lagged analysis, by using GEE, adjusted for age, BMI, and level of depressive symptoms at the previous assessment.

Female participants who had a disorder involving purging (PD or BN) were approximately twice as likely as their nondisordered peers to start using drugs or start binge drinking frequently (Table 2). For example, girls with PD were 2 times as likely (OR: 1.72 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.97–3.06]) and those with BN were 4 times as likely (OR: 3.91 [95% CI: 1.83–8.37]) to start using drugs. In addition, girls with EDNOS were also significantly more likely than their less disordered peers to start using drugs (OR: 1.52) or start binge drinking frequently (OR: 1.64). In the analyses with the lower frequency cutoff (monthly versus weekly), the associations with BN and PD were similar in magnitude (Table 3). For example, girls with monthly BN were >3 times more likely (OR: 3.76) than their peers to start using drugs, whereas girls with weekly BN were 4 times (OR: 3.91) more likely. In addition, in the analyses with the lower frequency cutoff, all types of eating disorders, including EDNOS, were associated with a significant increase in risk of starting to binge drink frequently.

In the primary analysis, only BED and EDNOS were associated with an increased risk of developing high depressive symptoms. When the frequency cutoff was relaxed from weekly to monthly, BED was the only disorder associated with an increased risk of developing high depressive symptoms, but the association was attenuated (OR: 1.77 vs 2.28).

Discussion

Among 8594 adolescent and young adult females throughout the United States, eating disorders were common and associated with an increased risk of developing a variety of adverse outcomes. Approximately 4.1% developed PD, 4.1% developed BED, and 1.5% developed BN. However, if we adhere to the current diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV, which do not consider PD or BED as distinct eating disorders, we would have only identified <2% of females as having an eating disorder. The underestimation is even more striking if we include EDNOS, which increases the prevalence of eating disorders to 13% to 21% among adolescent and young adult females.

BED is expected to be included as a recognized eating disorder in DSM-5; however, PD will be just 1 of several different types of eating disorders not elsewhere classified. The argument against including PD as a distinct category is that there are insufficient data on its prevalence, correlates, consequences, and treatment. Our data would suggest that the current plans for DSM-5 will result in a large underestimation of the true prevalence of eating disorders, albeit less of an underestimation than DSM-IV. Moreover, the increases in risk of developing psychopathology are similar for those with PD and BN, suggesting that it might be prudent to classify individuals into having disorders involving purging (ie, BN and PD) and those with disorders that only involve binge eating (ie, BED).

Treatment success is only moderate,31 and the health consequences of eating disorders are numerous32; thus, prevention is essential. Although Stice et al14 found that among 496 adolescent girls, those with full or subthreshold eating disorders had more impairment and distress than their peers, to the best of our knowledge this is the first article to examine prospectively whether full and subthreshold eating disorders are predictive of a range of specific adverse mental and physical health consequences. Our results suggest that primary prevention should focus on prevention of disorders of at least subthreshold severity. Future research should assess whether adolescents who binge and/or purge monthly need or benefit from treatment. Because treatment may differ according to severity of the disorder, a staging approach for eating disorders,33 similar to that used to classify hypertension,34 is warranted.

There are several limitations to this study. Our cohort is >90% white, and we relied on self-reports, which may have resulted in some misclassification. However, in a validation study conducted in this cohort, we observed that compared with interviews, self-reported purging had high sensitivity and specificity.23 The strengths of the study far outweigh the limitations. This is the largest longitudinal sample of adolescents and young adults with repeated eating disorder assessments published to date. Information on eating disorders, weight status, and mental health outcomes was collected every 12 to 24 months, and we also had information on a wide range of confounders.

We observed that BED and PD were relatively common among adolescent and young adult females. Not only were these disorders much more common than BN, but they were also associated with a substantially increased risk of numerous adverse outcomes. Thus, there is a need for both BED and PD to be recognized as distinct eating disorders or for PD to be combined with BN, rather than including 1 of these common and serious disorders in the large, heterogeneous, and often overlooked EDNOS group. Moreover, because only a minority of people with a psychiatric illness receive treatment for their disorder,35 and those with BED are particularly unlikely to seek treatment for their eating disorder,11 primary care clinicians need to be made aware of these disorders so that adolescents in need of treatment will be identified.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Heather Corliss, PhD, for her comments on the drug use analyses and the thousands of young people across the country participating in GUTS as well as their mothers.

Glossary

- BED

binge eating disorder

- BN

bulimia nervosa

- CI

confidence interval

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- DSM-5

fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- EDNOS

eating disorder not otherwise specified

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- GUTS

Growing Up Today Study

- MRFS

McKnight Risk Factor Survey

- OR

odds ratio

- PD

purging disorder

Footnotes

Dr Field contributed to the conception and design of the analysis and executed the data analysis. She also contributed to interpretation of the data, revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the submission. In addition, she and Dr Micali obtained funding for the project. Dr Sonneville contributed to the conception and design of the analyses presented in the article, as well as interpretation of the data, revisions of the manuscript, and final approval of the submission. Dr Micali contributed to the conception and design of the analysis presented in the article, as well as interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. Dr Crosby provided statistical expertise and contributed to the conception and design of the analysis. In addition, he contributed to the creation of variables and the interpretation of the data, revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the submission. Ms Swanson contributed to the conception and design of the analysis, interpretation of the data, revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the submission. Dr Laird contributed to the conception and design of the analysis presented in the article; she also provided statistical expertise and aided with the interpretation of the data, revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the submission. Dr Treasure and Ms Solmi contributed to the conception and design of the analysis presented in the article, as well as interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. Dr Horton contributed to the conception and design of the analysis. He provided statistical expertise and contributed to the interpretation of the data, revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the submission.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The analysis was supported by a research grant (MH087786-01) from the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Kendler KS. The epidemiology and classification of bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):599–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wonderlich SA, Joiner TE, Jr, Keel PK, Williamson DA, Crosby RD. Eating disorder diagnoses: empirical approaches to classification. Am Psychol. 2007;62(3):167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzog DB, Field AE, Keller MB, et al. Subtyping eating disorders: is it justified? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):928–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.le Grange D, Binford RB, Peterson CB, et al. DSM-IV threshold versus subthreshold bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(6):462–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilfley DE, Bishop ME, Wilson GT, Agras WS. Classification of eating disorders: toward DSM-V. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(suppl):S123–S129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eddy KT, Celio Doyle A, Hoste RR, Herzog DB, le Grange D. Eating disorder not otherwise specified in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(2):156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sanci L, Sawyer S. Prognosis of adolescent partial syndromes of eating disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(4):294–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field AE, Javaras KM, Aneja P, et al. Family, peer, and media predictors of becoming eating disordered. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(6):574–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Eating disorders, DSM-5 and clinical reality. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(1):8–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preti A, Girolamo G, Vilagut G, et al. ESEMeD-WMH Investigators . The epidemiology of eating disorders in six European countries: results of the ESEMeD-WMH project. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(14):1125–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, Jaconis M. An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(3):587–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Development: Eating Disorders. American Psychiatric Association 2012. Available at: www.dsm5.org/proposedrevisions/pages/eatingdisorders.aspx. Accessed May 4, 2012

- 16.Steiger H, Bruce KR. Phenotypes, endophenotypes, and genotypes in bulimia spectrum eating disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(4):220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mond J, Hay P, Rodgers B, Owen C, Crosby R, Mitchell J. Use of extreme weight control behaviors with and without binge eating in a community sample: implications for the classification of bulimic-type eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(4):294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keel PK, Brown TA, Holm-Denoma J, Bodell LP. Comparison of DSM-IV versus proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for eating disorders: reduction of eating disorder not otherwise specified and validity. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(6):553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Olmsted M, McFarlane T. The Impact of DSM-5 on EDNOS. Presented at the Conference on the Classification and Diagnosis of Eating Disorders; March 2009; Washington DC. (NIMH R13MH081447) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1997;278(13):1078–1083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Roberts SB, Colditz GA. Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):54–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shisslak CM, Renger R, Sharpe T, et al. Development and evaluation of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey for assessing potential risk and protective factors for disordered eating in preadolescent and adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25(2):195–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Field AE, Taylor CB, Celio A, Colditz GA. Comparison of self-report to interview assessment of bulimic behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35(1):86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Field AE, Aneja P, Rosner B. The validity of self-reported weight change among adolescents and young adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(9):2357–2364 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ. 2007;335(7612):194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff L. The use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20:149–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell JE, Agras S, Crow S, et al. Stepped care and cognitive-behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(5):391–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keel PK, Brown TA. Update on course and outcome in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(3):195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maguire S, Touyz S, Surgenor L, et al. The Clinician Administered Staging Instrument for Anorexia Nervosa (CASIAN): development and psychometric properties. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(3):390–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ, National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium . Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]