Abstract

A-Kinase anchoring protein 150 (AKAP150) is required for the phosphorylation of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) by PKA or PKC in sensory neurons and, hence, affects TRPV1-dependent hyperalgesia under pathological conditions. Recently, we showed that the activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors sensitizes TRPV1 by enhancing serine phosphorylation through PKC in trigeminal nociceptors. In this study, we extended this observation by investigating whether AKAP150 mediates NMDA-induced phosphorylation of TRPV1 via PKC in native sensory neurons in the rat. By adopting a phospho-specific antibody combined with a surface biotinylation assay, we first assessed NMDA-induced changes in the phosphorylation level of serine 800 residues (S800) in TRPV1 delimited to cell surface membrane in cultured trigeminal ganglia (TG). The biotinylation assay yielded that the application of NMDA significantly increased the phosphorylation of S800 (p-S800) of TRPV1 at time points correlating with the development of NMDA-induced mechanical hyperalgesia [10]. We then obtained a siRNA sequence against AKAP150 that dose-dependently down-regulated the AKAP150 protein. Pretreatment of TG culture with the siRNA, but not mismatch sequences, prevented the NMDA-induced phosphorylation of serine residues of total TRPV1 as well as S800 of membrane bound TRPV1. We confirmed that AKAP150 coimmunoprecipitated with TRPV1 and demonstrated that it also co-immunoprecipitated with NMDA receptor subunits (NR1 and NR2B) in TG. These data offer novel information that the activation of NMDA-induced TRPV1 sensitization involves p-S800 of TRPV1 in cell surface membrane in native sensory neurons and that AKAP150 is required for NMDA-and PKC-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 S800. Therefore, we propose that the NMDA receptor, AKAP150, and TRPV1 forms a signaling complex that underlies the sensitization of trigeminal nociceptors by modulating phosphorylation of specific TRPV1 residues.

Keywords: Nociceptor, Sensitization, Peripheral, Rat

1. Introduction

Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member I (TRPV1) is a ligand-gated, non-selective cation channel with a high permeability for Ca2+ and is activated by capsaicin, noxious heat, acid and various lipids [1-4]. The role of TRPV1 in pain sensation has been rigorously studied [5-6]. The function of TRPV1 is regulated by multiple G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) found in sensory neurons. For example, the augmentation of TRPV1 function by a type I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR5) in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) has been proposed to serve as the underlying mechanism for thermal hyperalgesia [7]. Other GPCR such as protease activated receptor 2 and neurokinin receptor sensitize TRPV1 through PKC activation and enhance pain behaviors [8-9]. We have recently reported that the activation of NMDA receptors leads to PKC-dependent phosphorylation of serine residues of TRPV1 in TG neurons, which provides an intracellular mechanism for TRPV1 sensitization and the development of orofacial mechanical hyperalgesia [10]. Thus, TRPV1 serves as a downstream integrator for signals arising from not only GPCR, but also from another ligand-gated ion channel in sensory neurons.

A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) families are comprised of scaffolding proteins that anchor receptors and signaling molecules to physiological substrates [11]. AKAP79/150 is a member of AKAP family that binds to the regulatory subunit of PKA and PKC [12-14]. AKAP150, the rodent homolog of human AKAP79, is ubiquitously expressed in the brain and modulates several ion channels such as voltage-gated M-type K+ channels, L-type Ca2+ channels and acid-sensing ion channels expressed in neurons [15-17]. AKAP150 is also expressed in sensory neurons and mediates phosphorylation of TRPV1, an event that underlies nociceptor sensitization [18-19]. Knocking down AKAP150 in trigeminal sensory neurons significantly attenuates PKA sensitization of TRPV1 activity and the administration of an AKAP150 antagonist reduces thermal hyperalgesia in rats [20]. Interestingly, the activation of GPCR results in the formation of the PKC-AKAP150 signaling complex, which modulates TRPV1 phosphorylation/sensitization in DRG neurons [19]. These findings suggest that AKAP150 is a key molecule required for TRPV1 modulation by intracellular signals arising from upstream receptors or channels.

In this study, we examined whether AKAP150 is also involved in NMDA-induced phosphorylation of serine residues of TRPV1 in TG neurons. Of the two serine residues in TRPV1that are phosphorylated by PKC, i.e. S502 and S800, the phosphorylation of S502 requires AKAP150 [19]. However, it is not known whether AKAP150 also targets S800. By taking advantage of the specific antibody that detects phosphorylation at S800 (p-S800) combined with a biotinylation assay, we examined whether the activation of NMDA receptors results in changes in p-S800 of TRPV1 at the surface membrane in an AKAP150 dependent manner in cultured TG neurons.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Primary TG culture

Male Sprague Dawley rats (200-250g) were used for primary TG culture as described previously [10]. TG were minced in cold Hanks's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and incubated in 5 ml of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F-12 containing collagenase and trypsin in a shaking incubator at 37°C for 30 min. TG extracts were mechanically dissociated and resuspended in the culture medium before plating on a 12 well plate coated with laminin. Dissociated TG neurons were maintained with DMEM/F-12 media containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cultures were used in immunoprecipitation experiments and biotinylation assays three to four days after plating.

2.2. Biotinylation of cell surface proteins

To examine changes in proteins localized to the plasma membrane, we performed biotinylation as described previously [21-22]. Briefly, dissociated TG cells were washed three times in cold PBS. For membrane protein biotinylation, TG cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) in PBS at 4°C for 30 min. To quench the reaction, cells were washed three times with cold PBS containing 100 mM glycine. Next, TG cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail followed by centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 min. The 100-150 μg of collected lysate was incubated with streptavidin cross linked to agarose beads (Pierce) for 2hr at 4°C. The beads were then washed twice with lysis buffer, and eluted with LDS loading buffer by heating at 100°C for 5 min. The membranes were incubated with antibody against p-S800 TRPV1antibody (1:500, polyclonal, anti-rabbit, Cosmo) for three days at 4°C. The specificity of this antibody is previously verified [23]. In order to normalize the amount of protein loaded and to examine contamination of cytosolic components in the biotinylation assay, the stripped membranes were incubated with GAPDH antibody (1:5000, monoclonal, anti mouse, Sigma). For the relative quantification of p-S800 TRPV1, GAPDH level of the corresponding sample was used as the normalization control.

2.3. siRNA preparation and transfection

The siRNA construct of AKAP150 was made by Thermo Scientific (Dharmacon). The sequence of the sense strand of AKAP150 siRNA was GCAUGUGAUUGGCAUAGAA-dTdT. The efficiency of this sequence in knocking down AKAP150 has been demonstrated in TG [20]. Isolated TG neurons were transfected with either AKAP150 siRNA or mismatch (MM, silencer-1, Ambion) using RNAi reagent (Invitrogen) as instructed by the manufacturer. TG neurons were transfected with two doses of the siRNA sequence (0.05 nM, 0.1 nM) or MM as a negative control for 24 hr.

2.4. Immunoprecipitation and co-immunoprecipitation

TG cultures were treated with lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail. To extract protein, the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min. The protein concentration of the cell lysate was measured using a Bio-Rad protein assay reagent kit. The sample proteins were immuonoprecipitated with TRPV1 antibody (1 μg, polyclonal, anti-rabbit, Calbiochem) overnight at 4°C, and then with protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Santa Cruz) for 2hr. LDS loading dye including SDS was added and boiled at 100 °C for 5 min to elute proteins from the bead complex. The denatured protein was then fractionated on a 4-12% gradient NuPAGE electrophoresis gel and blotted onto a PVDF or Nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked and incubated overnight at 4°C with a monoclonal phosphor-serine antibody (1:500, monoclonal, anti-mouse, Santa Cruz). The bound primary antibody was detected with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. The membranes were re-probed with anti-TRPV1 (1:1000, polyclonal, anti-rabbit, Calbiochem) following a stripping process to examine the same amount of running proteins. The immunocomplex was visualized using ECL reagent (Amersham) and recorded on X-ray film. The band signals on the film were scanned and quantified with Image J software. When normalized to p-Ser, the re-probed TRPV1 on the same membrane was used as a loading control.

For co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments involving AKAP 150 and NMDA receptors, lysates were incubated with anti-AKAP150 (2 μg, polyclonal, anti-rabbit, Upstate) for 4hr at 4°C and then followed the same protocol described above for immunoprecipitation. The following antibodies were used: NR1 (1:500, monoclonal, anti-mouse, Millipore), NR2B (1:500, monoclonal, monoclonal anti-mouse, Millipore) and TRPV1 (1:500, polyclonal, anti-goat, Santa Cruz). The specificities of these antibodies have previously been established [24-27].

2.5. Data analysis

For immuonoprecipitation studies, serine phosphorylation levels of each sample were normalized to TRPV1 in the same sample. In biotinylation experiments, p-S800 TRPV1 expression level of each sample was normalized to GAPDH in the same lysate. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks was used to detect statistical differences between treatments. Dunnett's comparison test was used for post-hoc analysis. Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test was performed for two group comparisons. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 NMDA induced PKC-mediated phosphorylation of S800 of TRPV1 in TG culture

In our previous study, we demonstrated that the activation of NMDA receptors leads to PKC-dependent phosphorylation of serine residues of TRPV1 in rat TG neurons [10]. In this study, we further investigated whether the application of NMDA in TG culture increases the phosphorylation of a specific serine residue, S800 of TRPV1 via PKC. In order to evaluate the level of phosphorylation of functional TRPV1, we developed an analysis quantifying phosphorylation of S800 in a membrane-delimited TRPV1 following biotinylation. Treatment of cultured TG neurons with PMA, a PKC activator, robustly increased the p-800 of TRPV1 compared to the non-treated sample (Fig. 1A). GAPDH was not detected in biotinylation samples, which suggests minimal contamination of the cytosolic component in our preparation (data not shown). Using these methods, we assayed p-S800 levels at 15, 30 and 45 minutes following the application of NMDA and compared to that of the baseline condition without the NMDA. The NMDA application resulted in a significant increase in the surface level of p-S800 at 15 and 30 minutes (H=12.038, p=0.007; Fig 1B), time points during which NMDA-induced mechanical hyperalgesia is prominent [10]. The increase of p-S800 was prevented when NMDA was co-applied with GF10920X, a PKC inhibitor (Fig 1C). These results showed that the activation of NMDA receptors leads to the phosphorylation of S800 in membrane bound TRPV1 via PKC in rat TG neurons.

Figure1. NMDA-induced PKC-mediated phosphorylation of S800 of cell surface membrane delimted TRPV1 in cultured rat TG neurons.

A-B. PMA, a PKC activator (A) or NMDA (B) increased expression of p-S800 TRPV1 in biotinylated samples from TG culture.(Upper panels) Representative immunoblot of p-S800 TRPV1 in biotinylated (surface) or GAPDH in corresponding total lysates (TL) following PMA treatment (1 μM) or NMDA (200 μM) as indicated. (Lower panels) Percent change in intensity ratio between p-S800 TRPV1 and GAPDH in the same TL (total lysate). PMA or NMDA treated group were normalized to non-treated group. C. GF109203X inhibited the increase of p-S800 TRPV1 expression by NMDA. (Upper panels) Representative immunoblot of p-S800 of TRPV1treated with or without GF109203X following NMDA treatment as indicated. Percent change in intensity ratio between serine 800 and GAPDH in the same TL (total lysate) (bottom). The intensity of GF109203X-treated group was normalized to that of non-treated group in the same blot (n=5 for each group, * p < 0.05)

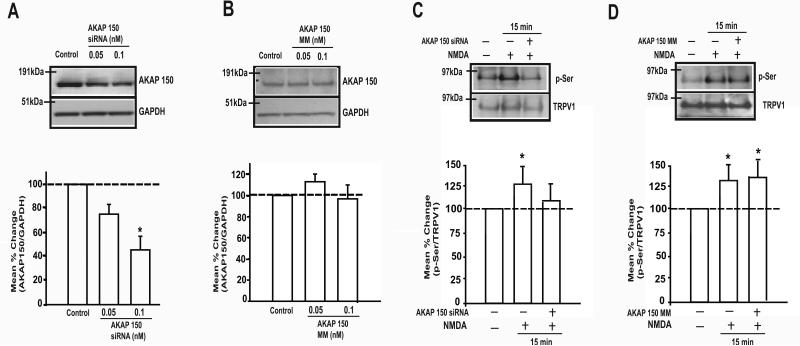

3.2. AKAP150 is involved in NMDA-mediated serine phosphorylation of TRPV1 in TG

Since AKAP150 is a key scaffolding protein for PKC-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 in sensory neurons [28] we examined whether AKAP150 is required for NMDA-mediated serine phosphorylation of TRPV1. First, we performed a siRNA-mediated gene silencing experiment to knock down AKAP150 expression in TG. To examine the efficiency of the AKAP150 siRNA, TG neurons were treated with two doses of AKAP150 siRNA or MM sequence for 24 hr. The siRNA dose-dependently down-regulated AKAP150 expression in TG (Fig 2A). However, MM treatment under the same condition did not alter the AKAP150 expression (Fig 2B).

Figure 2. Knock-down of AKAP150 suppressed the phosphorylation of total serine of TRPV1 in TG neurons.

A-B. Representative immunoblots of AKAP150 expression (upper) and percent changes in intensity ration between AKAP150 and GAPDH (bottom) following pretreatment of cultured TG neurons with siRNA against AKAP 150 (A) or mismatch (B). Control groups represent neurons that were not transfected. siRNA and mismatch group data were normalized to the control data in the same blot (n=5 per group * p < 0.05). C-D. Representative immunoblot of serine phosphorylation and re-probed TRPV1 treated with siRNA (C) or mismatch (D) (upper panel). Percent change in intensity ratio between phosphor-serine (p-Ser) and re-probed TRPV1 (bottom panel). siRNA and mismatch group data were normalized to control group in the same blot (n=6 per group, * p < 0.05).

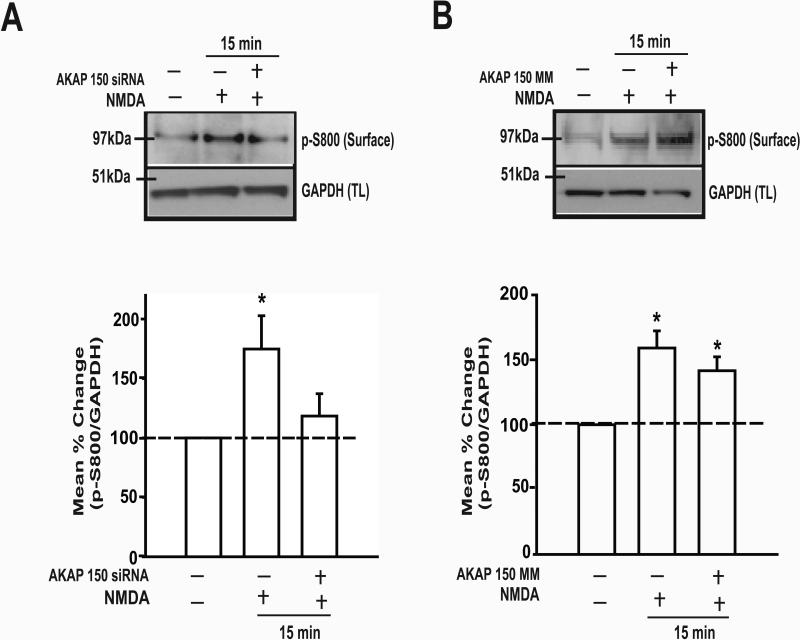

Previously, we showed that the application of NMDA increase the phosphorylation of TRPV1 at serine, but neither threonine nor tyrosine, residues, assessed in total lysate from TG cultures [10]. Treatment of TG cultures with the siRNA against AKAP150 blocked the NMDA-induced increase in serine phosphorylation of TRPV1 (Fig 2C). The MM treatment failed to block the NMDA effect on p-Ser (Fig 2D). We then treated TG cultures with the AKAP150 siRNA to examine the linkage between AKAP150 and TRPV1 S800 upon the activation of NMDA receptors. The siRNA against AKAP150, but not the MM control, effectively blocked the NMDA-induced p-S800 of TRPV1 (Fig 3A,B). Our data indicated that AKAP150 is required for PKC-mediated serine phosphorylation, specifically at S800, of TRPV1 following NMDA receptor activation.

Figure.3. Knock-down of AKAP 150 attenuated the phosphorylation of S800 of TRPV1 delimited to the plasma membrane of TG neurons.

Representative immunoblot (upper lane) of p-S800 of TRPV1 following pretreatment with siRNA (A) or mismatch (B) following NMDA treatment. Percent change in intensity ratio between p-S800 TRPV1 and GAPDH (bottom panel). The level of p-S800 of TRPV1 was evaluated in biotinylated sample (Surface) while GAPDH was assessed in total lysate (TL) obtained from the same sample. Control groups represent neurons that were neither transfected nor treated with NMDA. siRNA and mismatch group data were normalized to control group in the same blot. (n=5 per group, * p < 0.05).

3.3. AKAP150 forms protein-protein complex with NMDA receptor subunits and TRPV1 in TG

Since our data suggest that NMDA receptor, TRPV1 and AKAP150 may form a multi-protein complex, we examined this possibility using co-immunoprecipitation assay. In pull-down TG samples, AKAP150 co-immunoprecipitated with NMDA receptor subunit NR1 as well as NR2B (Fig. 4A and B). Furthermore, AKAP 150 also formed a protein complex with TRPV1 (Fig. 4C). Along with our previous data demonstrating the interaction between TRPV1 and NMDA receptors [10], these results suggest that AKAP150, NMDA receptors and TRPV1 form a multi-protein complex in TG neurons.

Figure.4.

AKAP150 forms protein-protein complexes with NMDA receptors and TRPV1 in rat TG neurons. After TG lysates were immunoprecipitated with AKAP 150 antibody, each sample was immunobloted with NR1 antibody (A), NR2B antibody (B), TRPV1 antibody (C). Each membrane was re-probed with AKAP 150 antibody.

4. Discussion

Both NMDA receptors and TRPV1 play a major role in the development of nociceptor sensitization [4,29]. We have previously demonstrated that the two important receptor-channel systems interact together and may operate as functional units in trigeminal ganglia [10]. The channel-channel interaction involving NMDAR receptor and TRPV1 offers a novel mechanism by which nociceptors are sensitized by excess glutamate, released during injury or inflammatory condition. However, detailed cellular mechanisms that link the two receptors need to be further characterized. In the present study, we demonstrated that the activation of NMDA receptors in TG neurons increases the phosphorylation of S800 of TRPV1, and that a scaffolding protein, AKAP150 is required in the interaction between TRPV1 and NMDA receptors. These results further consolidate specific interactions between NMDA receptors and TRPV1 in nociceptors and further support their concerting roles in hyperalgesia.

Phosphorylation of TRPV1 has been considered as a major mechanism that accounts for TRPV1 sensitization and various second messenger pathways have been associated with TRPV1 phosphorylation [30-32]. PKC phosphorylates TRPV1 at S502, S800 [23, 32-33], and threonine (T) 704, whereas PKA activation results in the phosphorylation of S502, S116, T144 and T370 residues [30, 34]. CaMKII activation also leads to phosphorylation of TRPV1 at S502, T370 and T704 [31]. Activation of NMDA receptors sensitizes TRPV1 by serine phosphorylation via pathways involving PKC and CaMKII, but not PKA in TG [10]. Therefore, of the three potential serine phosphorylation residues, S800 and S502 are likely substrates of PKC invoked by NMDA receptor activation.

In the present study, we provided new evidence that NMDA receptor activation leads to phosphorylation of TRPV1 at S800 localized in the surface membrane of TG neurons. Although the functional consequences of the increase in p-S800 were not investigated in this study, it has been shown that the NMDA-induced serine phosphorylation is highly correlated with the development of NMDA-induced mechanical hyperalgesia arising from craniofacial muscle tissue [10]. Furthermore, the PKC-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 at S800 following neurokinin-1 receptor activation leads to the potentiation of capsaicin-evoked substance P release in DRG neurons [35]. Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that the increase in p-S800 by PKC results in hyperexcitability of trigeminal nociceptors. However, the possibility of phosphorylation of TRPV1 at S502 still remains since the increase of non-specific serine phosphorylation of TRPV1 by NMDA application cannot be solely attributed to the change at S800.

The modulation of TRPV1 by intracellular enzymes such as PKA, PKC, and phosphatase calcineurin depend on the formation of signaling complex between TRPV1 and the scaffolding protein AKAP150, binds to TRPV1 C-terminal in nociceptors [19]. For example, the formation of PKC-AKAP150 complex is necessary for the phosphorylation of S502 of TRPV1 on the surface membrane following the activation of bradykinin receptors [19]. The enhancement of TRPV1 function is blocked when the AKAP150 binding to TRPV1 is prevented or the AKAP150 is selectively down regulated in sensory neurons [36]. These studies suggest that AKAP150 may function as a final common pathway coupled to TRPV1, on which signals arising from various inflammatory mediators converge. Consistent with this suggestion, the dose of siRNA that effectively down-regulated AKAP150 protein in TG prevented the NMDA-induced p-Ser and specifically p-S800 of TRPV1 in this study. Thus, our data provided additional evidence that AKAP150 is a required element in NMDA receptor-PKC-mediated modulation of TRPV1.

The literature on scaffolding proteins and other associated proteins involved in the formation of protein complexes in nociceptors is not extensive, hence, the precise nature of protein-protein interactions among various receptors and channels can only be speculated at this point. Our co-IP experiments showed that AKAP150 associated not only with TRPV1, but also with NMDA receptor subunits in TG. Since TRPV1 and NMDA receptors co-immunoprecipitate in TG [10], the present data suggest that AKAP150, TRPV1, and NMDA receptors are in close proximity to each other. AKAP150 is involved in the modulation of AMPA and NMDA receptors in the brain [37-38] and an AKAP150-NMDA receptor complex involving PSD-95 was reported in brain neurons [39]. Our results also opens a possibility of modulation in the opposite direction in which TRPV1 activation resulting in enhanced function of NMDA receptors in sensory neurons. In conclusion, our data showed that the activation of NMDA receptors induces phosphorylation of S800 of TRPV1, and that scaffolding proteins, such as AKAP150 tethers the two ligand-gated channels into complexes, which may serve as an important mechanism for the formation of ‘functional units’. Such functional units composed of multiple proteins may modulate nociceptor excitability in response to various pro-inflammatory mediators. This outcome informs us that the region of TRPV1 phosphorylation by the scaffolding protein or the scaffolding protein linkage may be novel targets for modulating nociceptive responses.

Highlights.

NMDA receptor activation leads to the phosphorylation of S800 of TRPV1 in trigeminal ganglia.

The NMDA-induced TRPV1 phosphorylation at S800 requires a scaffolding protein, AKAP150.

The NMDA receptor subunits NR1 and NR2B form a protein-complex with AKAP150.

TRPV1 and NMDA receptor interaction provides a biochemical basis for nociceptor sensitization.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by NIH Grant RO1DE16062(JYR)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Caterina MJ, Schmacher, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung MK, Jung SJ, Oh SB. Role of TRP channels in pain sensation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:615–36. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schumacher MA. Transient receptor potential channels in pain and inflammation: therapeutic opportunities. Pain Pract. 2010;10:185–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu HJ, Bhave G, Gereau RW. Prostaglandin and protein kinase A-dependent modulation of vanilloid receptor function by metabotropic glutamate receptor 5: potential mechanism for thermal hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7444–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07444.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amadesi S, Cottrell GS, Divino L, Chapman K, Grady EF, Bautista F, Karanjia R, Barajas-Lopez C, Vanner S, Vergnolle N, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptor 2 sensitized TRPV1 by protein kinase-Cepsilon- and A-dependent mechanisms in rats and mice. J Physiol. 2006;575:555–71. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Cang CL, Kawasaki Y, Liang LL, Zhang YQ, Ji RR, Zhao ZQ. Neurokinin-1 receptor enhances TRPV1 activity in primary sensory neurons via PKCepsilon : a novel pathway for heat hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2007;31:12067–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, Saloman JL, Weiland G, Chung MK, Ro JY. Functional interactions between NMDA receptors and TRPV1 in trigeminal sensory neurons mediate mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat masseter muscle. Pain. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.015. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauman AL, Soughayer J, Nguyen BT, Willoughby D, Carnegie GK, Wong W, Hoshi N, Langeberg LK, Cooper DM, Dessauer CW, Scott JD. Dynamic regulation of cAMP synthesis through anchored PKA-adenylyl cyclase V/VI complexes. Mol Cell. 2006;23:925–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku CY, Sanborn BM. Progesterone prevents the pregnancy-related decline in protein kinase A association with rat myometrial plasma membrane and A-kinase anchoring protein. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:605–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie G, Raufman JP. Association of protein kinase A with AKAP150 facilitates pepsinogen secretion from gastric chief cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1051–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.4.G1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faux MC, Rollins EN, Edwards AS, Langeberg LK, Newton AC, Scott JD. Mechanism of A-kinase-anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) and protein kinase C interaction. Biochem J. 1999;343:443–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Bal M, Bierbower S, Zaika O, Shapiro MS. AKAP79/150 complexs in G-protein modulation of neuronal ion channels. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7199–211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4446-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveria SF, Dell'Acqua ML, Sather WA. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron. 2007;55:261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chai S, Li M, Lan J, Xiong ZG, Saugstad JA, Simon RP. A Kinase-anchoring protein 150 and calcineurin are involved in regulation of acid-sensing ion channels ASIC1 and ASIC2a. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22668–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703624200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandao KE, Dell'Acqua ML, Levinson SR. A-kinase anchoring protein 150 expression in a specific subset of TRPV1-and CaV 1.2-positive nociceptive rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:81–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.22692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Li L, McNaughton PA. Proinflammatory mediators modulate the heat-activated channel TRPV1 via the scaffolding protein AKAP79/150. Neuron. 2008;59:450–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeske NA, Diogenes A, Ruparel NB, Fehrenbacher JC, Henry M, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. A-kinase anchoring protein mediates TRPV1 thermal hyperalgesia through PKA phosphorylation of TRPV1. Pain. 2008;138:604–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Jeske NA, Hargreaves KM. Transient receptor potential TRPA1 channel desensitization in sensory neurons is agonist dependent and regulated by TRPV1-directed internalization. J Physiol. 2007;583:175–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haapasalo A, Sipola I, Larsson K, Akerman KE, Stoilov P, Stamm S, Wong G, Castren E. Regulation of TRKB surface expression by brain-derived neurotropic factor and truncated TRKB isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43160–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandadi S, Tominaga T, Numazaki M, Murayama N, Saito N, Armati PJ, Roufogalis BD, Tominaga M. Increased sensitivity of desensitized TRPV1 by PMA occurs through PKCepsilon-mediated phosphorylation at S800. Pain. 2006;123:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popescu G, Auerbach A. The NMDA receptor gating machine: lessons from single channels. Neuroscientist. 2004;3:192–8. doi: 10.1177/1073858404263483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beutler LR, Wanat MJ, Quintana A, Sanz E, Bamford NS, Zweifel LS, Palmiter RD. Balanced NMDA receptor acitivity in dopamine D1 receptor (D1R) and D2R-expressing medium spiny neurons in required for amphetamine sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4206–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101424108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herin GA, Aizenman E. Amino terminal domain regulation of NMDA receptor function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung MK, Lee J, Duraes G, Ro JY. Lipopolysaccharide-induced pulpitis up-regulates TRPV1 in trigeminal ganglia. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1103–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034511413284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeske NA, Patwardhan AM, Ruparel NB, Akopain AN, Shapiro MS, Henry MA. A-kinase anchoring protein 150 controls protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and sensitization of TRPV1. Pain. 2009;146:301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du J, Zhou S, Coggeshall RJ, Carlton SM. N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced excitation and sensitization of normal and inflamed nociceptors. Neuroscience. 2003;118(2):547–62. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhave G, Zhu W, Wang H, Brasier DJ, Oxford GS, Gereau RW. cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates desensitization of the capsaicin receptor (VR1) by direct phosphorylation. Neuron. 2002;35:721–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung J, Shin JS, Lee SY, Hwnag SW, Koo J, Cho H, Oh U. Phosphorylation of vanilloid receptor1 by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulates its vanilloid binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7048–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo DH, Jung SJ, Zhu MH, Park CK, Kim YH, Oh SB, Lee CJ. Direct activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1(TRPV1) by diacylglycerol (DAG) Mol Pain. 2008;4:42. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Numazaki M, Tominaga T, Toyooka H, Tominaga M. Direct of phosphorylation of capsaicin receptor VR1 by protein kinase C epsilon and identification of two target serine residues. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13375–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rathee PK, Distler C, Obreja O, Neuhuber W, Wang GK, Wang SY, Nau C, Kress M. PKA/AKAP/VR-1 module: A common link of Gs-mediated signaling to thermal hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4740–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04740.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang HB, Li YS, Miyano K, Nakata Y. Phosphorylation of TRPV1 by neurokinin-1 receptor agonist exaggerates the capsaicin-mediated substance P release from cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuropharmacol. 2008;55:1405–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnizler K, Shutov LP, Van Kanegan MJ, Merrill MA, Nichols B, McKnight GS, Strack S, Hell JW, Usachev YM. Protein Kinase A anchoring via AKAP150 is essential for TRPV1 modulation by forskolin and prostaglandin E2 in mouse sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4904–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0233-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharyya S, Biou V, Xu W, Schluter O, R.C. A critical role for PSD-95/AKAP interactions in endocytosis of synaptic AMAP receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:172–81. doi: 10.1038/nn.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Y, Zhang M, Lim IA, Hall DD, Allen M, Medvedeva Y, McKnight GS, Usachev YM, Hell JW. AKAP150-anchored PKA activity is important for LTD during its induction phase. J Physiol. 2008;586:4155–64. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colledge M, Dean RA, Scott GK, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK-AKAP complex. Neuron. 2000;27:107–19. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]