Abstract

As life expectancy increases for adolescents ever diagnosed with AIDS due to treatment advances, the optimum timing of advance care planning is unclear. Left unprepared for end-of-life (EOL) decisions, families may encounter miscommunication and disagreements, resulting in families being charged with neglect, court battles and even legislative intervention. Advanced care planning (ACP) is a valuable tool rarely used with adolescents. The Longitudinal Pediatric Palliative Care: Quality of Life & Spiritual Struggle study is a two-arm, randomized controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of a disease specific FAmily CEntered (FACE) advanced care planning intervention model among adolescents diagnosed with AIDS, aimed at relieving psychological, spiritual, and physical suffering, while maximizing quality of life through facilitated conversations about ACP. Participants will include 130 eligible dyads (adolescent and family decision-maker) from four urban cities in the United States, randomized to either the FACE intervention or a Healthy Living Control. Three 60-minute sessions will be conducted at weekly intervals. The dyads will be assessed at baseline as well as 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-months post-intervention. The primary outcome measures will be congruence with EOL treatment preferences, decisional conflict, and quality of communication. The mediating and moderating effects of threat appraisal, HAART adherence, and spiritual struggle on the relationships among FACE and quality of life and hospitalization/dialysis use will also be assessed. This study will be the first longitudinal study of an AIDS-specific model of ACP with adolescents. If successful, this intervention could quickly translate into clinical practice.

Keywords: adolescents, advance care planning, HIV/AIDS, decision making, family intervention, pediatric palliative care

1. Introduction

Improved treatments for HIV/AIDS means newly diagnosed adolescents are potentially living well into middle to late adulthood [1,2,3]. Nevertheless, a significant number of adolescents are living with AIDS in the United States. In 2009, the CDC estimated that there were 10,144 adolescents aged 13–24 years living with AIDS [4]. The majority of these were male (65% aged 13–19; 88% aged 20–24) and African-American (68% aged 13–19; 62% aged 20–24) [4]. An AIDS diagnosis increases the risk of death from an overwhelming infection or following a chronic illness [5]. Consequently, prognosis is difficult to estimate and mortality is uncertain, underscoring the importance of Advance Care Planning (ACP1) and palliative care interventions for these youth. With the increase in complex, chronic conditions, palliative care has been redefined as “specialized medical care for people facing serious and chronic illness, aiming to improve quality of life (QOL2) for patients and families.” It is appropriate at any age and stage of a serious illness and can be provided with curative treatment [10]. Declining mortality can lead to a false belief that with access to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), End of Life (EOL3) issues cease to be of great concern [11]. Medical breakthroughs have expanded the timeframe for palliative care, blurring the definition of EOL [11]. Due to risk for HIV associated neurological disorders [12], it is recommended adolescents participate in EOL care decision-making early in the illness course. This is consistent with recommendations of the Institute of Medicine’s report on When Children Die [13] and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines [14]. Regarding end of life decision making, studies have shown adolescents are interested, capable, and competent in their ability to participate in research and medical decision making [6–9].

Results from our prior research identified adolescents’ needs and wishes [15]. The Lyon Advance Care Planning Survey assesses adolescent and family thoughts and needs around ACP and EOL care. Although when compared to healthy adolescents, chronically ill adolescents (i.e., those with HIV, cancer, sickle cell) were significantly more likely to state they prefer to wait to have these discussions until their first hospitalization from their illness or if dying, the majority still preferred having these discussions earlier in the illness course [15]. From this preliminary work, Lyon and colleagues developed the FACE4 protocol, a model of communication and decision-making, sensitive to adolescents’ evolving maturity, which weighs the benefits and drawbacks of EOL choices in a structured and safe way, eliciting differences in congruence between the adolescent with HIV and their family [16–18]. Operationally defined, family refers to the surrogate decision-maker or the person who will make decisions for the adolescent if he or she cannot speak for him/herself. Families in the intervention knew what their adolescent wanted for EOL care at statistically higher rates, compared to controls. FACE adolescents reported feeling significantly better informed about EOL decisions than controls. This pilot study also overcame barriers engaging African-American families in EOL research [17]. Overall, results demonstrated feasibility, adaptability [16] and safety [18].

2. Objectives of the FACE study

FACE shifts [16–18] clinical practice paradigms, being the first structured and individualized model for adolescents living with a life-limiting condition to meet recommendations and guidelines from the AAP [14]. Current practice and standard of care defers the timing of advance care planning to the physician and is contingent on the comfort level of the physician in having these conversations, or leaves it up to the patient to initiate it on their own. When these plans are not in place, the following practices are standard of care: Adolescents aged 18 and over are given an advanced directive in the emergency department by a hospital clerk or an advanced directive is mailed to them on their 18th birthday by their medical provider. Teens may have little comprehension of what the form entails (e.g., a DNR) and their families may not know the form has been completed. Compared with existing methods, FACE offers a novel methodology that is culturally sensitive, developmentally appropriate [1–2], family-based and standardized. The intervention is theoretically based in Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Stress and Coping Theory, [19] and Leventhal’s Theory of Self-Regulation [20], which prepares adolescents and their families for EOL decision-making. This study fills the knowledge gap [20] of effective communication among adolescents and surrogate decision-makers.

The Longitudinal Pediatric Palliative Care: Quality of Life & Spiritual Struggle is funded by a R01 grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health. This study builds upon prior studies [15–18] by: assessing if FACE primed ongoing discussion and continuing review of treatment preferences; evaluating the hypothesized mediators and moderator of FACE outcomes; confirming the efficacy of FACE with a new group of possibly medically unstable or hospitalized adolescents with AIDS; collecting data on those who declined participation or had no surrogate; preventing bias by assuring blindness of research assistants (RA) to random assignment; eliminating “ceiling and floor effects” on some measures; having two measures of spirituality; and assessing the impact of loss of a loved one to AIDS.

The primary aim of the study is to evaluate the long term efficacy of the FACE intervention on congruence in EOL treatment preferences between adolescents with AIDS and their family, decisional conflict about EOL decisions, quality of communication about EOL care, and Quality of Life (QOL). Our second aim is to evaluate the possible mediating and moderating effects of spiritual struggle, threat appraisal and HAART medication adherence on the relationship of the FACE intervention with QOL and hospitalization/dialysis use.

2.1. Hypotheses

The hypothetical assumptions of the FACE trial were based on extensive review of previous literature, the theoretical framework of the Transactional Stress and Coping Theory, the Theory of Self-Regulation, and results from our pilot study [12]. Evidence shows that congruence is high between patient preferences of those with a living will [21] or expressed through a surrogate [22] and the care actually received before death [23]. Our pilot results supported the feasibility of this intervention in a similar sample and suggested trends toward increasing completion of advance directives for families who took part in the FACE intervention [16,18]. The Transactional Stress and Coping Theory suggests that under conditions of chronic and severe stress, positive religious coping facilitates positive reappraisal of the difficult situation, which helps to support positive psychological states [24]. Research and theory suggest that chronic spiritual suffering will diminish the potential positive impact of the FACE intervention on study outcomes quality of life (QOL) and hospitalization/dialysis.

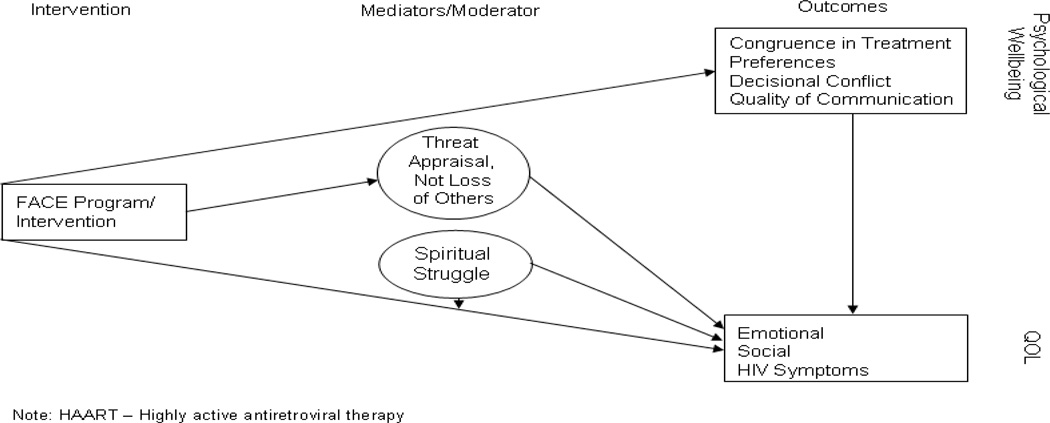

Hypotheses related to our primary aim are as follows (See Figure A.1). Compared to an active control, FACE will relieve psychological suffering as measured by:

-

1.A:

Increased congruence in treatment preferences between adolescents with AIDS and their families.

-

1.B:

Decreased decisional conflict regarding EOL decision making for future medical treatment in adolescents with AIDS.

-

1.C:

Increased quality communication about EOL care.

-

1.D:

Maximized QOL.

Figure A.1.

Transactional Stress & Coping Theory: Model of Coping with AIDS through Problem Solving

Our hypotheses related to Aim 2 are as follows:

-

2.A:

In addition to the direct effects, FACE will also indirectly affect QOL through dimensions of threat appraisal (See Figure A.1).

-

2.B:

FACE will have stronger effects on the QOL measures among patients who have less spiritual struggle. (See Figure A.1).

-

2.C:

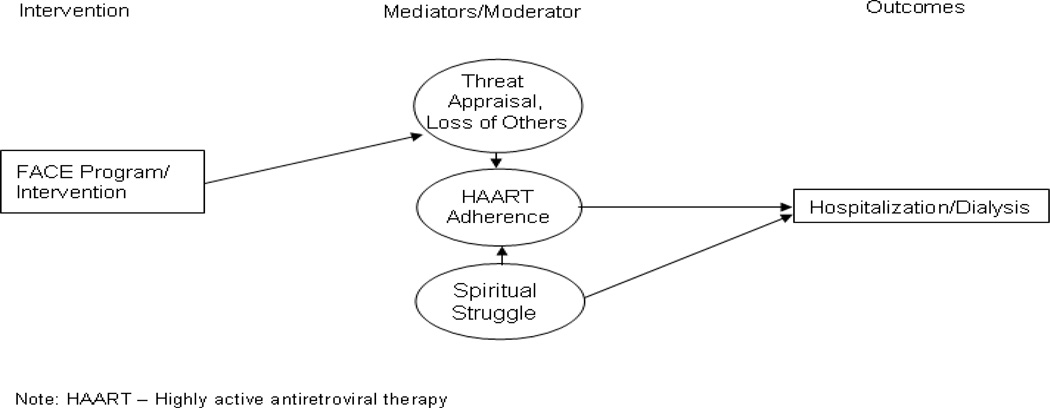

Spiritual struggle will directly increase the chance of hospitalization/dialysis and indirectly increase the chance of hospitalization/dialysis though decreased adherence to HAART. High threat appraisal, particularly the subscale “loss of others,” is hypothesized to increase HAART adherence which will lead to a decrease in the chances of being hospitalized or needing dialysis. Our pilot study findings support this hypothesis [16–18] (See Figure A.2).

Figure A.2.

Transactional Stress and Coping Theory: Model of Coping with AIDS through Problem Solving

3. Study Design

3.1. Overview

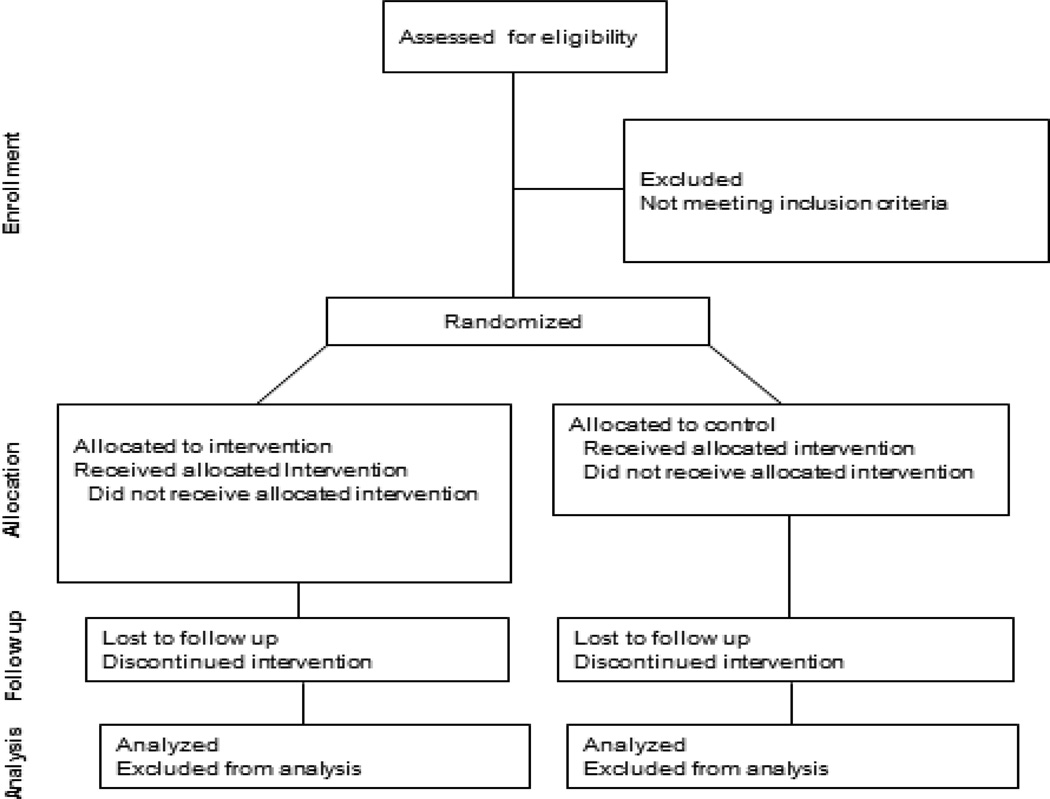

A two-arm randomized controlled clinical trial (RCCT) will be used to examine the FACE intervention on study outcomes among adolescents with AIDS and their family over 18 months post-intervention. Adolescents with AIDS and their families will be screened to prospectively examine primary outcomes. 130 adolescent/family dyads will be enrolled in the study and randomized into either the FACE intervention or Healthy Living Control (HLC) condition with the goal of obtaining data from approximately 91 dyads at 18 months for statistical analyses (Figure B.1). A RCCT design with a control group was chosen as the most appropriate method for determining the effectiveness of the FACE intervention. The time matched control condition will be able to account for the possible effect of the intensity and duration of interactions in the FACE intervention that has previously been shown to occur in these types of trials [25]. Additionally, using a time matched control condition that does not include the experimental components of the FACE intervention (DS-ACP guided by the Transactional Stress and Coping Theory) will allow for examination of the effectiveness of the intervention by comparing it to a similar curriculum in the amount of professional involvement and format.

Figure B.1.

Study Flow

3.2. Inclusion of Women and Minorities

The gender distribution for adolescents with AIDS at the study sites is approximately 59% male and 41% female. This study will recruit from all ethnic groups. There are increasingly large disparities in AIDS-related deaths by ethnic and racial groups [4, 26–27]. Among all adolescents, AIDS is one of the top ten causes of death for African Americans aged 15 to 24. [28]. Disparities also exist in palliative care, where African-Americans historically have experienced discrimination by health care institutions and may interpret discussion of Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders as an attempt at euthanasia or to deny beneficial care [29–32]. The aims of the present study are consistent with the 2011 NIH Strategic Plan for HIV Related Research [33], as we hypothesize FACE will reduce health disparities by providing access to palliative care and improve quality of life for disproportionately affected minorities, as well as increase involvement of minorities historically underrepresented in EOL research.

3.3. Ensuring Safety of Minors and Adolescents in the FACE Study

Procedures for minor participation and the determination of competency have been established to ensure the safety of participating youth in the FACE study. As described in the inclusion/exclusion criteria, adolescents with cognitive or developmental impairment, clinically significant depression, suicidal or homicidal thoughts, psychosis, or who are in the foster system will be excluded from participation on this study. In addition, adolescents who are under the age of 18 will be required to provide assent and their legal guardian required to provide consent to study participation. Guardians of minor adolescents also will participate as the surrogate in the trial. FACE interventionists have also been trained and certified in the DS-ACP model to be especially sensitive to emotional issues that may arise, although no adverse events arose from our pilot that demonstrated the FACE intervention safety and efficacy [12]. The study has also been approved by each participating sites’ IRB and is reviewed twice a year by the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB).

3.4. Participant Dyads

Adolescents will be asked to choose a surrogate decision-maker to participate in the study, using the Disease Specific ACP guidelines [34]. Families commit to being in the study regardless of which condition they are randomly assigned.

3.5. Sites

Four sites identified for participation should enable us to recruit sufficient numbers of patients with AIDS for adequate statistical power and to increase the generalizability of the findings. Sites were identified based on: 1) urban sites with high rates of adolescents with AIDS; and 2) a history of recruiting, retaining and implementing with fidelity adolescent clinical trials. Based on review of each site, almost 80% of potential participants are African American with a smaller population of approximately 20% Hispanic or Latino.

Site research teams will be comprised of the site investigator and three research assistants (RAs). One RA will be trained to conduct the FACE intervention (RA-Interventionist) while another will be trained to conduct the Healthy Living Control group sessions (RA-Control). The third RA (RA-Assessor) will conduct follow-up assessments to prevent interviewer bias during the data collection period. The RA-Assessor will be blinded to which group the dyad is randomly assigned and procedures will be implemented to maintain blindness at each site.

3.6. Recruitment and retention

Dyadic/family studies pose a challenge as sometimes the patient wants to participate, but the family member does not or vice versa [35]. The FACE pilot study demonstrated a high level of recruitment of eligible dyads (92%) comparing favorably with adult EOL interventions in which only 30% to 47% of eligible patients participated [35–38]. In order to be sensitive to possible distress of families and adolescents living with AIDS as well as recruitment during the end of life, primary Health Care Providers (HCP) will not be involved in the recruitment of subjects to prevent any perception of coercion or desire to please the HCP. Participants will be screened for study participation based on the inclusion and exclusion established criteria (Table A.1) and approached for the study by trained RAs.

Each participating site study team has measures in place to help ensure a high retention rate. In addition, RAs committed to flexible schedules in order to meet family needs, including Saturdays, early mornings, and late evening appointments. Every effort will be made to schedule follow-up assessments (months 3, 6, 12, 18) to coincide with the standard of care 3-month clinical visits.

3.7. Randomization

To better control for site specific effects, pairs of eligible adolescent/family dyads will be randomized to either FACE or HLC groups using a 1:1 randomly permuted block design controlling for site and perinatal vs. behavioral mode of transmission. The permuted-block randomization or blocked-randomization is the most frequently used design for randomization of patients among the restricted randomization procedures [39–40]. Randomization will only occur once a dyad has completed all baseline procedures. Randomization will be performed by computer at the coordinating site utilizing the Children's Research Information System (CHRIS) database.

3.8. Participant Visits

At screening, the site team will be responsible for the informed assent/consent process prior to any study related procedures being completed. The screening assessments are anticipated to last 30 minutes. Following screening, eligible dyads will be scheduled to return the following week for completion of the baseline visit, or if the participants prefer, the baseline visit can occur right after screening. It is estimated that the baseline visit will last approximately 45 minutes. During this visit, demographic and potential blocking variables will be collected from participants for randomization. Based on the randomized group assigned, FACE and HLC participants will receive three 60–90 minute Sessions scheduled one week apart. Sessions 1–3 will be followed by process questionnaires administered by the randomization blinded RA-Assessor. Post-intervention follow-up visits at months 3, 6, 12, and 18 will be conducted to assess outcomes. Mode of transmission will be collected from the medical chart for stratification of the sample. Consistent with previous behavioral intervention studies, weekly visits were chosen for the intervention and control time points. The post-intervention or control visits were chosen to occur in tandem with adolescents’ routine clinic appointments in an effort to minimize participant appointment burden. Compensation will be given to the adolescent and surrogate members of each dyad separately. Adolescents and surrogates will each receive $25 for the baseline visit, each of the intervention/control sessions, and for the 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. They also each will receive $30 for the 12- and 18-month follow-up visits.

4.0. Assessment and outcome measures

Outcome assessments will be conducted at screening, baseline, following sessions 1–3, and post intervention follow-up visits, with the exception of the Statement of Treatment Preference and the Decisional Conflict Scale, which are also administered at the time of Session 2. See Table B.1 for a schedule of study assessment measures.

5.0. Interventions

5.1. Research Team (RA Interventionist, Control, & Assessor)

The intervention and control sessions used in the FACE study will be delivered by trained and certified facilitators at participating sites supervised by the site investigator. All interventionists will undergo training in study interventions. Prior to study activation, face-to-face training sessions were conducted at the coordinating site with all RAs participating in the FACE study. Training included orientation to the protocol and the standardized procedures. RAs for HLC were trained by the coordinating PI to conduct the Healthy Living Control session and RA-Assessors were trained to conduct follow-up assessments. RA-Interventionists received further training in a certification course for the Disease Specific-Advanced Care Planning (DS-ACP) required for Session 2 of the Respecting Choices Interview [34]. Training included online coursework, a classroom certification course, and validation of competency through video recorded role-play demonstrations. Booster training sessions are also scheduled.

5.2. FACE Intervention

Developed and adapted by Lyon and colleagues, FACE integrates specific essential elements of effective programs, including Briggs’ work with Respecting Choices [41], which are theoretically grounded, structured, and targeted at several systems simultaneously. The FACE intervention (Table C.1) offers a novel methodology compared to commonly implemented current practices in which adolescents 18 and over are presented with an advance directive document to consider/complete.

The three sessions will each be scheduled one week apart, ideally on the same day of the week at the same time to increase appointment attendance rates. All sessions will be conducted in a private office in the participating site clinic. A Manual of Operating Procedures for research interventionists has been developed for this study and provided to staff at each site, as well as more detailed Instructions to Investigators.

5.3. Health Living Control Group (HLC)

A healthy living control (HLC) curriculum will be utilized for the FACE study. Our pilot study of the FACE study established the efficacy of the FACE design, including the HLC condition. While the use of a HLC does have limitations, this approach is common and literature supports the use of HLC if the essential element of the intervention is not present in the control condition [42]. For the FACE intervention, the unique dyadic approach, guided by the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping [19], promotes an active, family-centered decision making process about advanced care planning. While the control condition will utilize a dyadic approach, control participants will not receive the theoretically guided intervention curriculum to promote family-centered shared decision making about advance care planning. Dyads randomly assigned to the HLC condition will also participate in weekly sessions conducted over a three-week period (Table B.2). Content reviewed during these sessions is not related to ACP or the FACE intervention. Rather, these sessions are based on the Bright Futures teaching materials provided by the AAP and include discussion of nutrition and safety tips.

5.4. Data safety monitoring plan

A thorough data safety monitoring plan will be developed and implemented in order to monitor participant safety, as well as data integrity. The Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) will meet annually to review the data and safety of the participants. Adverse events will be recorded by the site and reported to the principal investigator immediately as well as to the DSMB and/or local IRB if necessary.

5.5. Adverse Events

For the FACE study, a Serious Adverse Event (SAE) will be defined as “an emotional breakdown resulting in hospitalization or inpatient behavioral health services for emotional distress very likely/certainly related to study intervention.” An Adverse Event (AE) will be defined as endorsing one of the three intervention sessions as agreeing or strongly agreeing with it being “harmful” or “too much to handle.” An AE will also be defined as a participant endorsing disagree or strongly disagree for the following items on the satisfaction questionnaire after each intervention/control session: it was useful, it was helpful, I felt satisfied, I felt courageous, and it was worthwhile. Any SAE occurring during the conduct of the protocol will be reported immediately to the supervising licensed mental health professional as well as the principal investigator and the local IRB. AEs will be monitored to ensure that the AE was caused by the study intervention, and not some coincidental issue. AEs will be collected and reported to the principal investigator as well as the institutional IRB. Study implementation will be discontinued until a corrective plan of action will be implemented to minimize the likelihood of SAEs.

6.0. Data Management and Analysis

Collected data will be stored at the coordinating site. Teleforms (forms that can be scanned and data abstracted to an electronic database) will be used to record data.

6.1. Data Analytic Plan and Power Analysis

Analytical Plan

The aims will be evaluated longitudinally in a period of 18 months. Descriptive statistics will be used to characterize study participants overall and within intervention groups. Multivariate statistical analyses will be applied to assess the efficacy of the FACE.

Analytical Plan for AIM 1

Congruence in decision-making for future medical treatment will be assessed using Kappa coefficients. The impact of FACE on preference congruence, patient decisional conflict, and patient/family communication over time will be assessed using the Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models [43–44] that are desirable for analyzing longitudinal data with various types (numeric, dichotomous, ordinal, nominal, or count) of outcome measures. With appropriate time score coding, the unequal time intervals can be readily handled, and the model intercept will represent the outcome mean for the control group, and the main effect of intervention will represent the difference in outcome mean between the intervention and control groups at the end of the study period. The interaction between time score and the intervention will provide information about how the intervention affects rate of change in the outcome over time. Like traditional statistical methods (e.g., repeated measure analysis), GEE assumes missing completely at random (MCAR). If this assumption does not hold, a mixed-effect model that relies on approximating the marginal log likelihood by integral approximation through Gaussian quadrature can be used to model the longitudinal data assuming missing at random (MAR) [45]. MAR allows missing data to be dependent on observed outcomes, treatment assignments, covariates.

Analytical Plan for AIM 2

To test the mediating effects in the model shown in Figure A.1 (e.g., the indirect effect of FACE of QOL measured through threat appraisal), both the difference in coefficients and product of coefficients methods [46–48] in GEE models or mixed-effect models will be used. The moderating effects of spiritual struggle on the effects of the FACE (see figure A.1) will be tested by examining the interactions between these two variables. Path analysis modeling will be applied to test the model shown in Figure A.2 using the cross-sectional data collected at each follow-up interval. In addition, multi-process latent growth models (LGM) with robust estimator [49] will be applied to test the model shown in figure A.2 using longitudinal data. More specifically, the repeated measures of threat appraisal and HAART adherence will be used to model the growth trajectories of these two measures. How FACE would influence distal outcomes (e.g., hospitalization) through threat appraisal, and then through HAART adherence can be examined by the coefficient product of (slope coefficient of regressing the slope growth factor of threat appraisal trajectory on FACE)*(slope coefficient of regressing the slope growth factor of HAART adherence trajectory on the slope growth factor of threat appraisal trajectory)*(slope coefficient of regressing hospitalization on the slope growth factor of HAART adherence trajectory).

Sample Size and Power

Sample size estimation, widely used for longitudinal studies [43, 50–51], was applied. For a small within-subject correlation (ρ=0.20) and a moderate effect size (Δ=0.35) (based on the results of a pilot study [16], this assumed effect size is relatively conservative), the estimated sample size to achieve a power of 0.80 at 0.05 level is N=72 dyads for analyzing numeric outcomes. The corresponding sample size needed for detecting a response probability difference of 0.20 in dichotomous outcomes is N=52. Assuming up to 30% attrition (20% drop out; 10% deceased) in the baseline sample of N=130 dyads, the sample size at the 18-month follow-up (N=91 dyads) would ensure a statistical power of 0.80 or higher.

Benchmarks for success anticipated to achieve aims include: recruitment of half of the eligible patients and their parents during the study period; enrollment of 130 dyads for randomization; retention of 70% by 18-month assessment; and 90% data completion. Any lags will trigger identification of barriers and solutions, including possible recruitment from affiliated hospitals in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area.

7.0. Discussion

Prior research supports families being involved with EOL decision making and that adolescents have a mature understanding of death [52–57]. Furthermore, evidence indicates that children and adolescents (ages 10 to 20) can be involved with EOL decisions, understand the consequences of their decisions, and successfully participate in complex decisions involving themselves and others [58]. In our pilot R34, no differences by age (M=16 years) were found among outcome variables [16–18]. Methodological challenges and barriers included: fear of distressing the adolescent or emotions stirred up in all involved parties, and beliefs of inappropriate or harmful nature of EOL discussions with adolescents.

Research and theory suggest that chronic spiritual suffering, such as the belief that HIV is a punishment from God; will diminish the potential positive impact of the FACE intervention on study outcomes of QOL and hospitalization/dialysis as evidenced by Lyon and colleagues who studied adolescents’ use of spirituality as a means of coping with HIV [59–61]. Additionally, disparities exist in the use of palliative care by African-Americans [62–65]. If the proposed aims are achieved, the benefits of palliative care, particularly the relief of suffering and enhanced quality of life, will be extended to adolescents with AIDS who are disproportionately minorities [4, 26, 66–67].

The FACE study includes a number of features to account for methodological weaknesses that have limited previous palliative care studies. This intervention formally uses families in the adolescent’s decision making process unlike current clinical practice and much of the published research. Instead of being handed an advanced directive by a hospital clerk, we expect FACE will promote better comprehension of the subject matter and an engaging atmosphere for the adolescents and families. The dyad will be involved in conversations about treatment preferences, which can be shared with the adolescent’s health care provider. Small sample size has also been a limiting factor of palliative care studies among adolescents. FACE will utilize a larger RCCT for greater generalizability and to broaden assessed outcomes, including the impact of the loss of someone to HIV/AIDS and five of the eight domains (psychological, social, spiritual, cultural, ethical) relevant to EOL care [68]. The three remaining domains (structure and process of care, physical aspects, care of imminently dying patient) are already implemented at the study site facilities [66]. The study will also meet the needs of adolescents and families preparing for EOL and build on national guidelines for improving quality of spiritual care as a dimension for pediatric palliative care [13–14]. Regarding participant recruitment and retention, participants will be recruited from all transmission groups, with minority and underserved groups accounting for a significant portion of enrollment.

There are limitations to the FACE study that need to be taken into account. First, although the adolescent may be accustomed to routine clinic visits, the family may have greater difficulty maintaining scheduled appointments. We have tried to account for this problem by allowing dyads to be seen during the evenings and weekends. Also, attempts will be made to have study appointments occur on already regularly scheduled clinic visits. A participant withdrawal and replacement plan has also been formulated should participants prematurely withdraw from the study. Second, threats to validity may arise due to the sensitive nature of the topic and the RA-interventionists’ personal values about death and dying. Procedures are in place to ensure intervention fidelity to the Respecting Choices Interview across sites. Third, interviewer bias is a potential limitation when conducting behavioral research. FACE will attempt to limit this by blinding the RA-Assessor to randomization. Finally, selection bias may be a problem if those who choose to participate are more likely to want to be involved in shared decision making compared with those who choose not to participate. This will be evaluated by analysis of demographic data collected from those adolescents who choose not to participate.

8.0 Conclusion

The FACE trial will determine the impact of a facilitated conversation regarding EOL and ACP among adolescents with AIDS and their family on the adolescent patient’s quality of life. Should the FACE intervention prove to be beneficial for adolescents and their families, the potential impact on adolescent palliative care would be significant. If successful, study results will 1) advance understanding of the mechanisms of change that minimize suffering and maximize QOL; 2) improve the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care; 3) decrease health disparities in EOL care among minorities; 4) translate quickly into palliative care practice; and 5) be adaptable to other diseases which impact adolescents, including cancer, cystic fibrosis and Duchene Muscular Dystrophy (DMS).

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by grant number 1R01NR012711-01 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NINR. We thank the members of the FACE Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium, including Linda Briggs, Patricia Flynn, Nancy Hutton, and Larry Friedman.

Appendix I - Tables

Table A.1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Participants

| Adolescent | |

|---|---|

| Inclusion Criteria: | Exclusion Criteria: |

| 1. Between the ages of 14 to 21 who have been diagnosed with AIDS | 1. Age is <14 or ≥21 |

| 2. Aware of his or her HIV diagnosis | 2. Unaware of his or her HIV diagnosis |

| 3. Participant is not known to have an IQ <70 or to be developmentally delayed | 3. Participant has a known IQ < 70 or is developmentally delayed |

| 4. Participant is not currently in crisis or distress or has any other disabling condition (e.g., impaired short-term memory) confirmed by provider and/or social worker or indicated by the HIV Dementia Scale need citation | 4. Participant is in acute distress as confirmed by primary care provider and/or social worker |

| 5. Not currently experiencing symptoms of depression in the high-moderate to severe range, as assessed by the BDI-II citation | 5. Currently experiencing symptoms of depression in the high-moderate to severe range as assessed by the BDI-II citation |

| 6. Understands English | 6. Does not understand English well enough to understand the study |

| 7. Currently in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) | |

| 8. In foster care | |

| Legal Guardian/Surrogate | |

| 1. >21.0 years of age at enrollment | 1. ≤ 21 years of age at enrollment |

| 2. Participant is not currently in crisis or distress or has any other disabling condition (e.g. impaired short-term memory) confirmed by provider and/or social worker or indicated by the HIV Dementia Scale citation | 2. Legal Guardian/Surrogate does not have the mental or physical capacity to provide informed consent and/or study sessions as determined by the PI, social worker, or HIV Dementia Scale citation |

| 3. Not currently experiencing symptoms of depression in the high-moderate to severe range, as assessed by the BDI-II citation | 3. Currently experiencing symptoms of depression in the high-moderate to severe range as assessed by the BDI-II citation |

| 4. Understands English | 4. Does not understand English well enough to understand study |

| 5. Participant is not known to have an IQ < 70 or is not known to be developmentally delayed | |

| 6. Legal Guardian/Surrogate aware of adolescent’s HIV diagnosis | |

Table B.1.

List of Study Measures

| Measures | Participant Completion |

Time Point | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Data Interview | Adolescent & Surrogate | Screen | Demographic data collection |

| HIV Dementia Scale [69] | Adolescent & Surrogate | Screen, 4,5,6,7 | Rapid screener to identify HIV dementia |

| Psychological Interview [70] | Adolescent & Surrogate | Screen | Questions from the NIH Diagnostic Interview for Children –R to assess suicidality, homicidality, psychosis, & depression |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [71] | Adolescent & Surrogate | Screen, 4,5,6,7 | Assess symptoms of depression and severity |

| Beck Anxiety Scale (BAI) [72] | Adolescent & Surrogate | 0,4,5,6,7 | Assess severity of subjective, somatic, & panic related anxiety symptoms |

| Decisional Conflict Scale [73] | Adolescent | 0,2 | Measures the state of uncertainty about which course of action to take. Revised by Briggs to represent decision-making regarding future medical treatment. |

| Statement of Treatment Preferences [16] | Adolescent & Surrogate | 0,2,4,5,6,7 | Adapted during pilot study, based on expert and community advisory board, to express values and goals related to future decision-making re: frequently occurring situations specific to HIV/AIDS |

| Medication Adherence Self Report Inventory – MASRI [74] | Adolescent | 0,4,5,6,7 | Self-report measure of medication adherence, using the Visual Analogue Scale for estimated adherence in the past month. |

| The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™-1I [75–76] | Adolescent & Surrogate | 0,4,5,6,7 | Measures health related QOL in children and adolescents |

| Quality of Life Assessment – Revised, ages 12–20 [77] | Surrogate | 0,4,5,6,7 | HIV-related symptom subscale of the GHAC |

| General Health Assessment for Children–GHAC [78] | Adolescent | 0,4,5,6,7 | HIV-related symptom subscale is a self-report measure assessing QOL |

| Threat Appraisal Scale [79] | Adolescent | 0,4,5,6,7 | Estimate of adolescent’s threat appraisal of HIV when adolescent learned of HIV diagnosis |

| Brief Multidimensional Measurement of Relgiousness/Spirituality - BMMRS-adapted [80] | Adolescent & Surrogate | 0,4,5,6,7 | Assesses the construct of spiritual suffering in adolescents. Coping domain will be used for study purposes. |

| Brief-Religious Coping Questionnaire - Brief RCOPE [81–83] | Adolescent and Surrogate | 0,4,5,6,7 | Assesses positive and negative religious coping methods. Study will use 7-item version that assesses negative religious coping. |

| Satisfaction Scale [16] | Adolescent & Surrogate | 1,2,3 | Developed in pilot study to assess satisfaction with study intervention/session |

| Quality of Patient-Interviewer Communication [84] | Adolescent & Surrogate | 1,2,3 | Tool used to evaluate quality of communication between adolescent/surrogate and the interviewer |

| Medical Chart Abstraction | Chart Abstraction | 0,4,5,6,7 | Mode of transmission, CD4 count, viral load, hospitalization or dialysis since last study visit |

0=Baseline; 1=Session 1; 2=Session 2; 3=Session 3; 4=3-month follow up; 5=6-month follow up; 6=12-month follow up; 7=18-month follow up

I=Interview; CR=Chart Review; Q=Questionnaire

Table C.1.

FAmily CEntered (FACE) Advance Care Planning Intervention

|

FOUNDATION:Session 1 Lyon Family Centered Advance Care Planning (ACP) Survey © [15] - Adolescent and Surrogate Versions to increase which engages the participant in EOL questions. |

GOALS: Session 1

|

PROCESS: Session 1

|

| Session 2 Disease-Specific Advance Care Planning (DS ACP) Interview® [34] |

Session 2

|

Session 2* Stage 1 assesses the adolescent’s understanding of current medical condition, prognosis, complications; Stage 2 explores adolescent’s philosophy regarding EOL decision-making and their understanding of the facts; Stage 3 reviews rationale for future medical decisions the adolescent would want the surrogate to understand/act on; Stage 4 uses the Statement of Treatment Preferences to describe clinical situations common to AIDS and related treatment choices; Stage 5 summarizes the discussion/ need for future discussions as situations/preferences change. Gaps in information are identified and referrals are made. *This session will be videotaped and/or audio-recorded |

| Session 3 The Five Wishes® [85] is a legal document that helps a person express how they want to be treated if they are seriously ill and unable to speak for him/herself. Unique among living will and health agent forms - it looks to all of a person's needs: medical, personal, emotional, spiritual. citation |

Session 3

|

Session 3* For adolescents under the age of 18, the Five Wishes © must be signed by their legal guardian. Processes, such as labeling feelings and concerns, as well as finding solutions to any identified problem, are facilitated. Appropriate referrals are made to help resolve disagreements over decision-making (e.g. a hospital ethicist or their doctor) or spiritual issues (e.g. a hospital chaplain or their clergy). *These sessions may include other family members or loved ones. |

Table C.2.

Healthy Living Control Condition

|

FOUNDATION: Session 1 Developmental History The Barkley Developmental History form [86] will be administered, with all medical questions removed from the developmental history as well as the information on mother’s pregnancy and the birth, to prevent any risk of contamination with the experimental FACE condition. |

GOALS: Session 1 To take a non-medical developmental history. The RA-Control will conduct the session in a structured interview format. To provide a control for time (approximately 60 minutes) and attention. |

PROCESS: Session 1

|

| Session 2 Safety Session Using the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures Counseling guides [87], participants will be asked questions about seat belt use, oral health, etc. Safety information will be provided following the questionnaire administration |

Session 2 To provide safety information using the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures counseling guides. Content in this review is not related to Advance Care Planning or the FACE intervention. |

Session 2* Structured questionnaires/information will be administered to the patient/surrogate dyad by the trained RA-Control together in a private room. The adolescent will be asked first, then the surrogate to parallel the structure of the intervention. *This session will be videotaped and/or audio-recorded |

| Session 3 Nutrition Session. Using the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures counseling guides [87], participants will be asked questions about nutrition. |

Session 3 To provide nutrition information using the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures counseling guides. Content in this review is not related to Advance Care Planning or the FACE intervention. |

Session 3 Structured questionnaires/information will be administered to the patient/surrogate dyad by the trained RA-Control together in a private room. The adolescent will be asked first, then the surrogate to parallel the structure of the intervention. |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Advanced Care Planning

Quality of Life

End of Life

Family Advanced Care Planning

References

- 1.Harrison K McD, Song R, Zhang X. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states.United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):124–130. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b563e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankar CV. Newly diagnosed HIV patients with no symptoms have good life expectancy. [Accessed June 2010];Reuters Health Information. Available at: /viewarticle/723870. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Sighem AI, Gras L, Reiss P, Brinkman K, de Wolf F. ATHENA national observational cohort study. Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:1527–1535. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control. 2009 HIV Surveillance Report. [Accessed August 2011];Slide Set: HIV Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults. 2011 ( http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/index.htm?source=govdelivery).

- 5.Brady MT, Oleske JM, Williams PL, Elgie C, Mofenson LM, Dankner WM, Van Dyke RB Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group219/219C Team. Declines in mortality rates and changes in causes of death in HIV-1 infected children during the HAART era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):86–94. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b9869f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santelli JS, Rogers AS, Rosenfeld WD, DuRant RH, Dubler N, Morreale M, et al. Guidelines for adolescent health research: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolsc Health. 2003;33:396–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weithron LA. Children’s capacities to decide about participation in research. IRB. 1983;5:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake DR, Lemay CA, Kearney MH, Mazor KM. Adolescents’ understanding of research concepts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:533–539. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badzek L, Kanosky S. Mature minors and end-of-life decision making: a new development in their legal right to participation. J Nurs Law. 2002:8223–8229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McInturff B, Harrington L. Presentation of 2011 Research on Palliative Care. Washington, D.C.: Center to Advance Palliative Care & Cancer Action Network; 2011. Jun 22, Unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grady PA, Knebel AR, Draper A. End-of-life issues in AIDS: the research perspective. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:479–482. doi: 10.1177/014107680109400918. discussion 84–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyon ME, McCarter R, D’Angelo L. Detecting HIV associated neurocognitive disorders in adolescents: what Is the best screening tool? J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(2):133–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative Care for Children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon ME, McCabe MA, Patel K, D’Angelo LJ. What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):529. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, He J, D'Angelo L, McCarter R. Development, feasibility and acceptability of the Family-Centered (FACE) Advance Care Planning Intervention for adolescents with HIV. J Palliative Med. 2009;12:363–372. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, McCarter R, Briggs L, He J, D'Angelo L. Who will speak for me? Improving end-of-life decision-making for adolescents with HIV and their families. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e199–e206. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, et al. Is it safe? Talking to adolescents about death and dying. A 3-month evaluation of FAmilyCEntered (FACE) advance care planning - anxiety, depression, quality of life. HIV/AIDS. Research and Palliative Care. 2010;2:1–11. doi: 10.2147/hiv.s7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Shafer C. Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. Lay beliefs about health and illness; pp. 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krug R, Karus D, Selwyn PA, Raveis VH. Late stage HIV/AIDS patients’ and their familial caregivers’ agreement on the Palliative Outcome Scale. J Pain Symptom Management. 2010;39:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhoff KT, Kehl KA. Recruiting participants in end-of-life research. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;24 doi: 10.1177/1049909107300551. 515–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCareney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne Effect: a randomized, controlled trial. BMC. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control. 2009 HIV Surveillance Report. [Accessed August 2011];Slide Set: Pediatric HIV Surveillance (through 2009) 2011 ( http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/pediatric/index.htm?source=govdelivery).

- 27.Johnson AS, Hu X, Aharpe TT, Dean HD. Disparities in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among racial and ethnic minority youth. J Equity Health. 2009;2:4–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Vital Statistics System. LCWK1. Deaths, percent of total deaths and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 5-year age groups by race and sex: United States. 2006;52(9):69, 80, 91. 05/19/2009. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_tables.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazanec P, Tyler MK. Cultural considerations in end-of-life care: how ethnicity, age, and spirituality affect decisions when death is imminent. Am J Nurs. 2003;103:50–58. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200303000-00019. quiz 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krakauer EL, Crenner C, Fox K. Barriers to optimum end-of-life care for minority patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:182–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawley LM, Marshall PA, Lo B, Koenig BA. Strategies for culturally effective end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:673–679. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL. Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA. 2000;284:2460–2468. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed August 2011];FY 2011 Trans-NIH Plan HIV Related Research: Priority: Reducing HIV Related Disparities. :119–156. www.oar.nih.gov/strategicplan/fy2011.

- 34.Briggs L, Hammes BJ. Disease Specific-Advance Care Planning (DS-ACP): Facilitator Certification Training Manual: A Communication Skills Training Program. Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation, Inc.; 2010. [Accessed August 2011]. www.respctingchoices.org. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial 2009. JAMA. 302:746–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies B, Reimer JC, Brown P, Martens N. Challenges of conducting research in palliative care 1995. Omega (Westport) 31:263–273. doi: 10.2190/JX1K-AMYB-CCQX-NG2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudson P, Aranda S, McMurray N. Randomized controlled trials in palliative care: overcoming the obstacles. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001;7 doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.9.9301. 427–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMillan SC, Weitzner MA. Methodologic issues in collecting data from debilitated patients with cancer near the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:123–126. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zelen M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chron Dis. 1974;27:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagakos SW. Randomization and stratification in cancer clinical trials: an international survey. In: Buyse ME, Staquet MJ, Sylvester RJ, editors. Cancer Clinical Trials, Methods and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 1984. pp. 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briggs LA, et al. Patient-centered advance care planning in special patient populations: a pilot study. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang KZS. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1998. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Xie H, Fisher J. Multilevel Models: Applications Using SAS. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finney D. Probit Analysis: Statistical Treatment of the Sigmoid Response Curve. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A Simulation Study of Mediated Effect Measures. Multivariate Behav Res. 1995;30:41. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Methen L, Methen B. Mplus User’ Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Methen & Methen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied Mixed Models in Medicine. New York: Wiley & Sons, LTD; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang JX, Xie H, Fisher J. Multilevel Models: Applications Using SAS. Beijing, China: The China Higher Education Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146–9154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiener L, Ballard E, Brennan T, Battles H, Martinez P, Pao M. How I wish to be remembered: the use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1309–1313. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weinberger DR, Elvevag B, Giedd JN. The adolescent brain: A work in progress. [Accessed August 2011];Monograph The Naitonal Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. 2005 ww.frontline.org.

- 56.Kane JR. Pediatric palliative care moving forward: empathy, competence, quality, and the need for systematic change. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:847–849. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freyer DR. Care of the dying adolescent: special considerations. Pediatrics. 2004;113:381–388. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oaks LL, Fouladi M, Spunt SL, Church C, Furman WL. End-of-life care practices of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146–9154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kao ET, Lyon ME, D'Angelo LJ. Spiritual well-being as a determinant of HIV/AIDS clinical outcomes and psychological adjustment in inner-city adolescents infected with HIV. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:S15–S16. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bernstein K, Lyon ME, D'Angelo LJ. Spirituality and religion in adolescents with and without HIV/AIDS. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:S25. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lyon ME, Townsend-Akpan C, Thompson A. Spirituality and end-of-life care for an adolescent with AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15:555–560. doi: 10.1089/108729101753287630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krakauer EL, Crenner C, Fox K. Barriers to optimum end-of-life care for minority patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:182–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crawley LM, Marshall PA, Lo B, Koenig BA. Strategies for culturally effective end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:673–679. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL. Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA. 2000;284:2460–2468. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phillips RS, Hamel MB, Teno JM, et al. Patient race and decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments for seriously ill hospitalized adults. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med. 2000;108:14–19. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson AS, Hu X, Aharpe TT, Dean HD. Disparities in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among racial and ethnic minority youth. J Equity Health. 2009;2:4–18. [Google Scholar]

- 67.McConnell MS, Byers RH, Frederick T, et al. Trends in antiretroviral therapy use and survival rates for a large cohort of HIV-infected children and adolescents in the United States, 1989–2001. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:488–494. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134744.72079.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. [Accessed August 2011];Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Second Edition. http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org.

- 69.Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. HIV Dementia Scale: a rapid screening test. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:273–278. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. 2nd Ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 73.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional confiict scale. Med Dcis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16:269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PEDSQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Medical Care. 1999;37:126–139. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gortmaker SL, Lenderking WR, Clark C, et al. Development and use of a pediatric quality of life questionnaire in AIDS clinical trials: Reliability and validity of the general health assessment for children. In: Drotar D, editor. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents: Implications for Research and Practice. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lenderking WR, Testa MA, Katzenstein D, Hammer S. Measuring quality of life in early HIV disease: the modular approach. Qual Life Res. 1997;6:515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018408115729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Program for Prevention Research, Arizona State University. Manual for the Threat Appraisal Scale (TAS) Tempe, AZ: Program for Prevention Research, Arizona State University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harris SK, Sherrit LR, Holder DW, Kulig J, Schrier LA, Knight JR. Reliability and validity of the Brief Multidiminsional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality among adolescents. J of Religion and Health. 2007;47:438–457. doi: 10.1007/s10943-007-9154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality.Implications for physical and mental health research 2003. Am Psychol. 2003;58:64–74. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pargament KI. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, Greenlee H, Collier AC. The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: a study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. AIDS. 1999;13:1123–1131. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. [Accessed August 2011];Five Wishes. Aging with Dignity Web site. Retrieved from http://www.agingwithdignity.org/five-wishes.php.

- 86.Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Attention-Defecit Hyperactivity Disorder Workbook. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Third Edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]