Abstract

Inflammatory cells play important roles in progression of solid neoplasms including ovarian cancers. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) contribute to angiogenesis and immune suppression by modulating microenvironment. Ovarian cancer develops occasionally on the bases of endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory disease. We have recently demonstrated differential expressions of CXCR3 variants in endometriosis and ovarian cancers. In this study, we showed impaired CXCL4 expression in TAMs of ovarian cancers arising in endometriosis. The expressions of CXCL4 and its variant CXCL4L1 were investigated among normal ovaries (n = 26), endometriosis (n = 18) and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers (EAOCs) composed of clear cell (n = 13) and endometrioid (n = 11) types. In addition, four cases of EAOCs that contained both benign and cancer lesions contiguously in single cysts were investigated in the study. Western blot and quantitative RT-PCR analyses revealed significant downregulation of CXCL4 and CXCL4L1 in EAOCs compared with those in endometriosis. In all EAOCs coexisting with endometriosis in the single cyst, the expression levels of CXCL4 and CXCL4L1 were significantly lower in cancer lesions than in corresponding endometriosis. Histopathological study revealed that CXCL4 was strongly expressed in CD68+ infiltrating macrophages of endometriosis. In microscopically transitional zone between endometriosis and EAOC, CD68+ macrophages often demonstrated CXCL4− pattern. The majority of CD68+ TAMs in overt cancer lesions were negative for CXCL4. Collective data indicate that that CXCL4 insufficiency may be involved in specific inflammatory microenvironment of ovarian cancers arising in endometriosis. Suppression of CXCL4 in cancer lesions is likely to be attributable to TAMs in part.

Keywords: CXCL4, endometriosis, inflammatory microenvironment, ovarian cancer, tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)

Introduction

Inflammatory microenvironment is important for development of cancers. Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease in the women of reproductive ages.1,2 Most cases of endometriosis remain to be benign, however, it is well known that clear cell and endometrioid types of ovarian cancers frequently coexist with endometriosis.3,4 Such a condition is named as endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC). Pathological studies demonstrate that benign and malignant lesions are contiguously localized in the same cyst of EAOC.5 Molecular studies of endometriosis reveal that ovarian cancer cells and coexisting endometriosis glands share common genetic abnormalities.6,7 These findings support the notion that endometriosis may play some roles in ovarian carcinogenesis. Contrary to intensive studies of epithelial abnormalities in endometriosis, differential inflammatory microenvironment between endometriosis and EAOC remains to be poorly understood.

Recent studies have elucidated the importance of stromal components for cancer progression. For example, cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete various proinflammatory factors such as CXCL12 (SDF-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and some of these soluble factors attract bone marrow-derived cells to the lesion for tissue remodeling which supports cancer invasion and metastasis.8,9 Chemokines are important regulators of angiogenesis and immune cell recruitment.10-12 CXC chemokines without Glu-Leu-Arg (ELR) motif such as CXCL4 (PF-4), CXCL9 (Mig) and CXCL10 (IP-10) generally promote anticancer effects by exerting immune responses and anti-angiogenic properties.13-15 The main receptor for these chemokines is CXCR3. CXCR3 is expressed in various immune cell subsets,16,17 stromal cells including vascular endothelial cells,14,18,19 and some types of tumor cells.20-23 There are three CXCR3 variants, i.e., CXCR3A, CXCR3-alt and CXCR3B.24,25 CXCL9 and CXCL10 interact with CXCR3A, and CXCL11 interacts not only with CXCR3A but also with CXCR3-alt.25 CXCL4 is the main functional ligand for CXCR3B,24 and it also interacts directly with VEGF and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), exerting inhibitory effects on these angiogenic factors.15,26,27 Platelet α-granules are considered to be the major cellular source of CXCL4.28 In addition, CXCL4 is potentially localized in other stromal components such as lymphocytes and endothelial cells,29,30 and it interacts with a variety of immune cells like monocytes and neutrophils.31-33 Therefore, CXCL4 is expected to exert important pathophysiological effects against solid tumors and infections. We have recently found that CXCL4 and its receptor CXCR3B were downregulated in clear cell ovarian cancers.34 The results indicate that CXCL4-CXCR3B axis might be disturbed in this type of cancer.

Clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancers are frequently associated with endometriosis.3,5 In the present study, we investigated the expression of CXCL4 in endometriosis and EAOCs of these histological types. We found that CXCL4 was localized in macrophages infiltrating in endometriosis but was depleted from tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in EAOCs. Histopathological analysis revealed that CXCL4 was reduced in transitional zones between endometriosis and cancer in EAOCs. Impaired expression of CXCL4 in TAMs and inflammatory microenvironment of ovarian cancers arising in endometriosis are discussed.

Results

Expression of CXCL4 in controls, endometriosis and EAOCs

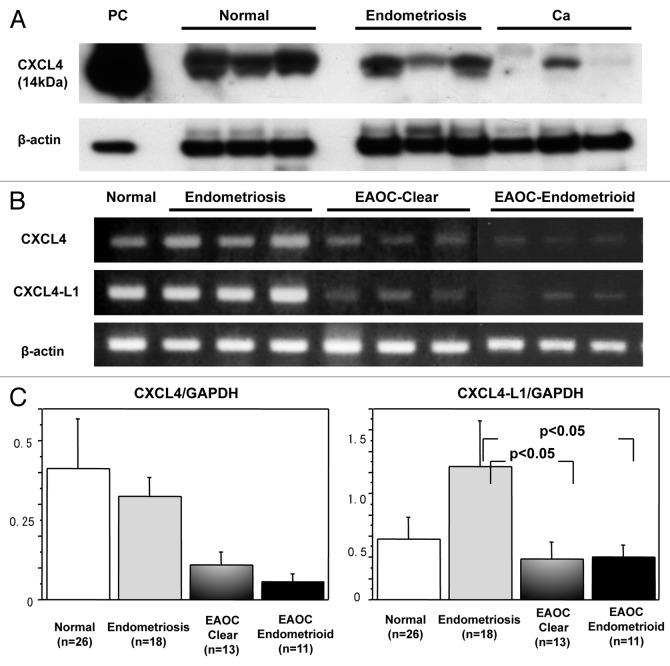

We had previously shown that CXCL4 was downregulated at mRNA level in clear cell cancers compared with normal ovaries and endometriosis.34 In the present study, western blot analysis was done to understand the expression of CXCL4 at protein level (Fig. 1A). In normal ovaries, CXCL4 bands were clearly detected in all except for two cases in which the bands were very weak or undetectable. In endometriosis, CXCL4 bands were detectable in all and they were as strong as those in normal ovaries. In clear cell EAOCs, CXCL4 bands were detectable in half cases, but three of them showed much weaker bands than those in normal and endometriosis. In the other half cases, the bands were not detectable. In endometrioid EAOCs, weak bands were detected in two cases, and in the others CXCL4 bands were undetectable.

Figure 1. Expression of CXCL4 in normal, endometriosis and cancer tissues. (A) western blot analysis is performed using anti-CXCL4 antibody that recognizes both CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1. Representative cases of normal, endometriosis and cancer tissues are shown. β-actin is used as a control. Platelet-derived protein is used as positive control. (B) Results of RT-PCR analysis are shown. CXCL4-specific and CXCL4-L1-specific primers are used, respectively. The PCR product samples were subjected to 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. (C) Real-time RT-PCR was performed and the expression levels of CXCL4 (left graph) and CXCL4-L1 (right graph) normalized by GAPDH were investigated among normal (n = 26), endometriosis (n = 18), clear cell cancer (n = 13) and endometrioid cancer (n = 11) tissues.

CXCL4-L1 is a variant of CXCL4, showing three amino acid divergence in the C-terminus which contains biding site to heparan sulfate proteoglycans.35 Although CXCL4-L1 is highly homologous to CXCL4, differential behavior has been reported; CXCL4-L1 is diffusible whereas CXCL4 preferentially remains associated to the cells.29,36 Currently, no antibody is available that can distinguish CXCL4-L1 from classical CXCL4 in a specific manner.29 The band of western blot is thought to be CXCL4 of both classical and variant types. Therefore, we investigated the expressions of CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 at mRNA level. In our previous study, we used CXCL4 primers amplifying common sequence region of both types.34 In the present study, CXCL4-specific and CXCL4-L1-specific precursor regions were amplified by RT-PCR, respectively. It was demonstrated that CXCL4-L1, as well as CXCL4, were expressed significantly in normal ovaries and endometriosis. On the contrary, the levels were much weaker in most of cancer cases (Fig. 1B). Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 were downregulated in both clear cell and endometrioid EAOCs. The expression level of CXCL4 was the highest in normal, followed by endometriosis (Fig. 1C, left). The result was consistent with our previous study of clear cell cancers using the primer set amplifying the common region of both variants.34 The expression level of CXCL4-L1 was shown to be the highest in endometriosis. The expression level of CXCL4-L1 was statistically different between endometriosis and EAOCs of clear cell and endometrioid types, respectively (Fig. 1C, right).

Downregulation of CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 in the cancer contiguously developed from endometriosis

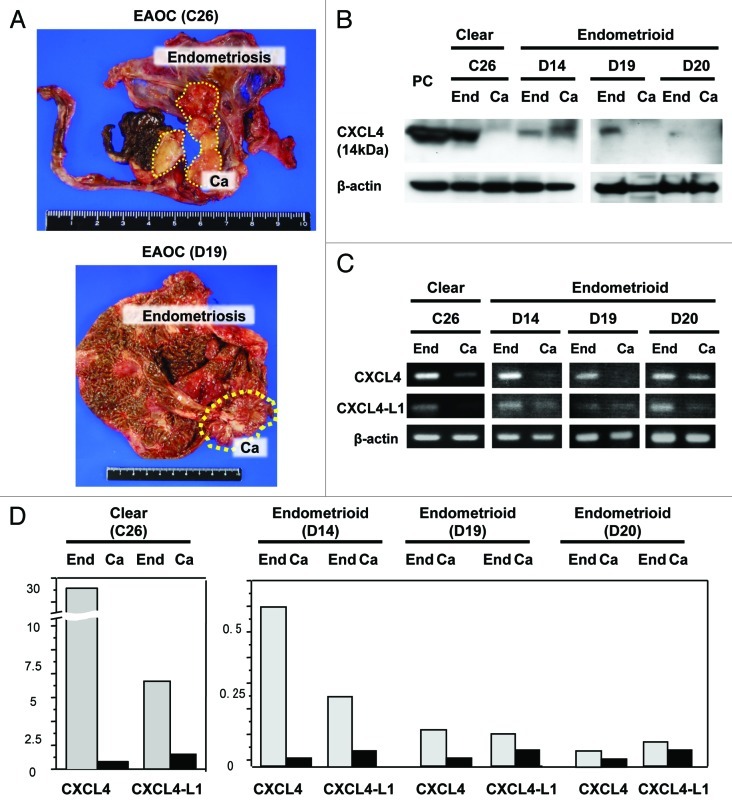

Downregulation of CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 in cancer lesions of EAOCs indicated that CXCL4-mediated signaling might be disturbed in the cancers arising on the bases of endometriosis. All these endometriosis samples (n = 18), however, were histologically benign and obtained from the patients without the history of cancers. It remained unknown whether endometriosis tissues co-existing with cancers show differential expression patterns of these chemokines compared with the corresponding cancers. Therefore, we investigated CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 in the endometriosis lesions co-existing with cancer. In four cases of EAOCs, cancer developed in a single endometriotic cyst (Fig. 2A). Histological analysis confirmed that the cancer developed contiguously in endometriosis lesion from benign epithelium to overtly malignant cells. Tissues were obtained from microscopically confirmed cancer lesions and endometriotic lesions, respectively, and mRNAs and proteins were isolated. Western blot analysis revealed that CXCL4 bands were detected at significant levels in all endometriosis but undetectable in the corresponding cancers except one in which CXCL4-like band in the cancer was detectable at higher molecular weight (Fig. 2B). RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR revealed that mRNAs of both CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 were suppressed markedly in these four cancer nests compared with those in corresponding endometriosis lesions (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2. Expression of CXCL4 in contiguously localized endometriosis and cancer lesions. (A) Macroscopic features of EAOCs (Case No. 10; C26, and No. 23; D19) developing contiguously from endometriosis in a single cyst are shown. The cancer nodule is indicated in yellow dotted circle. (B) western blot analysis is performed in 4 EAOCs composed of 1 clear cell and 3 endometrioid cancers and corresponding endometriosis. Platelet-derived protein is used as positive control. “End” indicates endometriosis and “Ca” indicates cancer of the same cyst. (C) Results of RT-PCR analyses of CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 are shown. The PCR products of endometriosis lesion (End) and coexisting cancer lesion (Ca) in the same cyst were subjected to 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. β-actin is used as an internal control. (D) Real-time RT-PCR was performed and the expressions of CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 normalized by GAPDH are shown. The chemokine levels are compared between endometriosis and corresponding cancer in each case. Gray bars indicate endometriosis and black bars indicate corresponding cancers.

Histological localization of CXCL4 in ovarian tissues

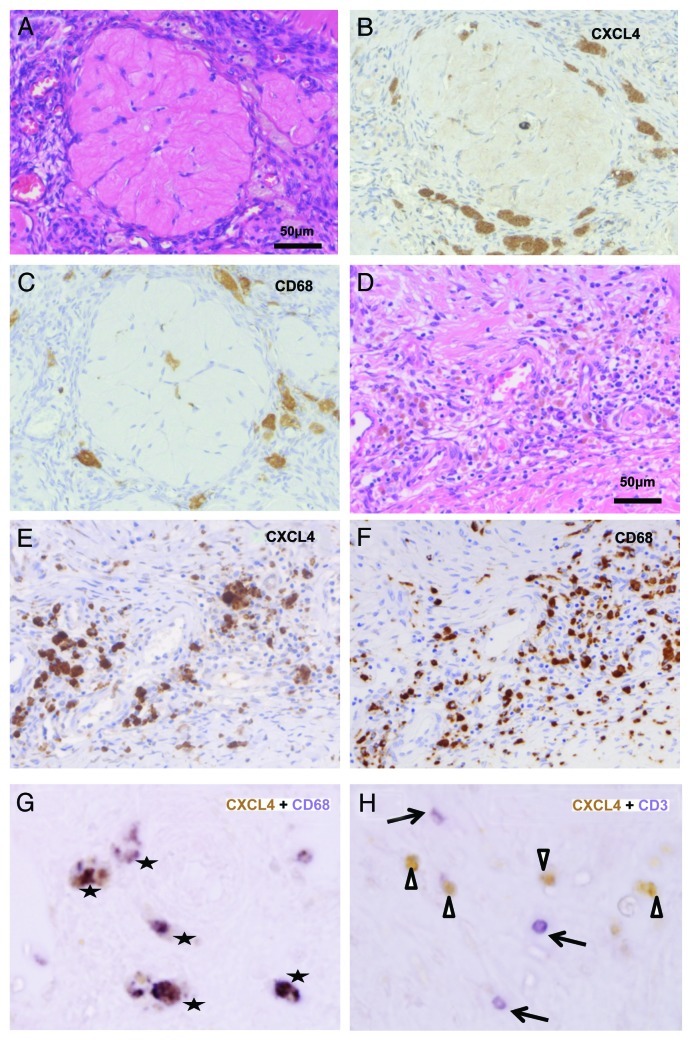

As mentioned above, CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1, in mature protein forms, show high amino acid homology. Although the antibody selectively recognizing CXCL4 or CXCL4-L1 is not available, these variants are known to be co-expressed in several human cell types at mRNA level.29 We performed immunohistochemical staining to understand histological localization of CXCL4. In normal ovaries, CXCL4 was expressed in foamy mononuclear cells (Fig. 3A and B). These cells were CD68+ macrophages infiltrated in the vicinity of corpus albicans (Fig. 3C), suggesting that CXCL4+ CD68+ macrophages might contribute to tissue physiology related to previous ovulation. T cells and B cells were not detectable in quiescent ovaries (data not shown). In endometriotic ovaries, cyst walls were infiltrated by mononuclear cells including hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Fig. 3D). Many CXCL4+ mononuclear cells were detectable in the lesions, and the same distribution pattern was observed in CD68 staining (Fig. 3E and F). Double staining confirmed that most of CXCL4+ cells were co-localized with CD68+ cells (Fig. 3G). CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells were also infiltrated significantly in inflammatory lesions. We investigated whether CXCL4 was also co-localized with these lymphocytes in endometriosis. The majority of CD3+ cells were negative for CXCL4 (Fig. 3H). Although CD8+ cells were often overlapped with CXCL4 cells, most of CXCL4+ CD8+ cells were morphologically larger than typical T cells, and they exhibited phagocytotic feature and were stained with CD68 (data not shown), suggesting that they were CD8+ macrophages.37,38 Distribution pattern of CD20+ B cells was different from that of CXCL4+ cells, and CD20+ cells were not overlapped with CXCL4+ cells (data not shown). It was strongly suggested that the main source of cell-bounding CXCL4 in endometriosis was CD68+ macrophage.

Figure 3. Histological localization of CXCL4 in normal ovary and endometriosis. (A) HE staining of a quiescent normal ovary. (B) CXCL4 is stained in foamy mononuclear cells around a corpus albicans. (C) Mononuclear cells are stained with CD68, consistent with macrophages (D) HE staining of an endometriosis. Chronic inflammatory cells are diffusely infiltrated. (E) CXCL4 is stained in infiltrating mononuclear cells with large cytoplasm. (F) Distribution pattern of CD68 staining cells is almost similar to that in CXCL4. (G) Double staining of CXCL4 (brown in DAB) and CD68 (purple in BCIP/NBT) in an endometriosis. Overlapped cells are marked with stars. (H) Double staining of CXCL4 (brown in DAB) and CD3 (purple in BCIP/NBT) in an endometriosis. The most of CXCL4+ cells (arrowheads) are not co-localized with CD3+ cells (arrows).

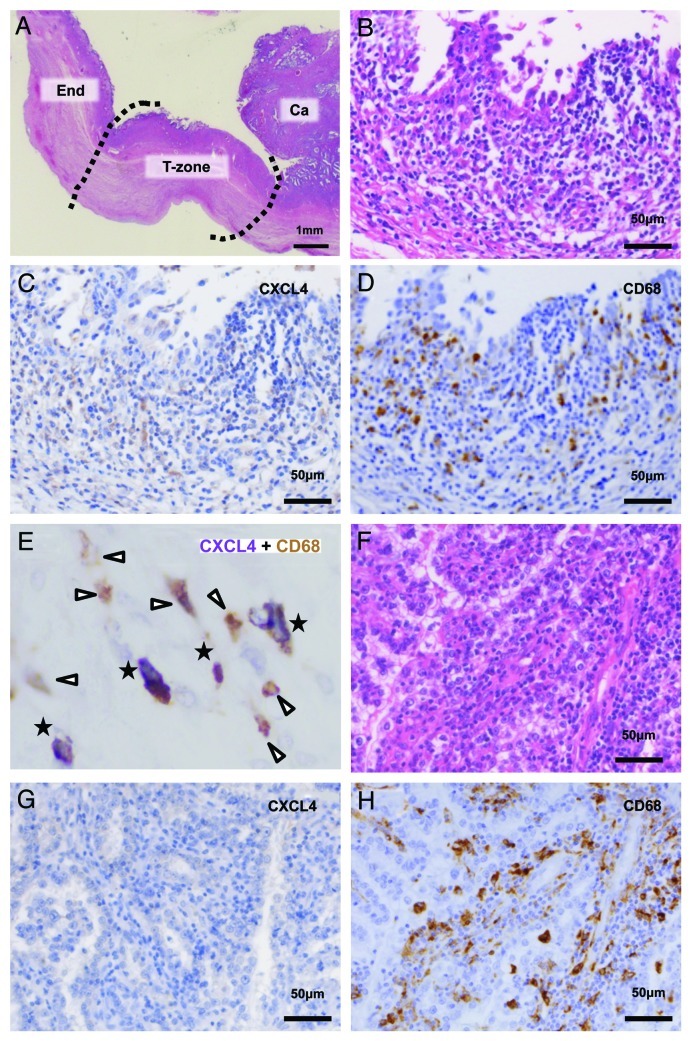

Next, the expression of CXCL4 in EAOCs was investigated. Microscopically transitional zone lay in the vicinity of the cancer nodule (Fig. 4A). In all EAOCs, cyst walls were infiltrated by heterogeneous mononuclear cells including hemosiderin-laden macrophages. The staining pattern of CXCL4 in non-cancerous area was almost similar to those in endometriosis, and the extent of infiltration was varied among cases. In transitional zones, however, CXCL4+ cells were sparse or even lacked in most of the cases (Fig. 4B and C). Some CD68+ cells were overlapped with CXCL4+ cells (Fig. 4E, stars), but there were also numbers of CXCL4low CD68+ cells and CXCL4− CD68+ cells (Fig. 4E, arrowheads). In overt cancer areas (Fig. 4F), CXCL4+ cells were either few in number or undetectable (Fig. 4G). The depletion of CXCL4 was highlighted in the cancer nests diffusely infiltrated by CD68+ TAMs (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4. Histological localization of CXCL4 in EAOCs. (A) HE staining of contiguous lesions of EAOC. “End,” endometriosis; “T-zone,” transitional zone; “Ca,” cancer (B) HE staining of the transitional zone of EAOC. Epithelial cells show nuclear atypia and proliferate slightly. (C) CXCL4 staining in a serial section of the transitional zone. CXCL4+ cells are few in number and low in intensity. (D) CD68 staining in a serial section of the transitional zone. A number of CD68+ macrophages are infiltrated. (E) Double staining of CXCL4 (purple in BCIP/NBT) and CD68 (brown in DAB) in the transitional zone of EAOC. CXCL4+ CD68+ cells are marked with stars. Other infiltrating CD68+ cells (arrowheads) are either CXCL4low or CXCL4−. (F) HE staining of the cancer lesion of EAOC. (G) CXCL4 staining in a serial section of the cancer lesion. Immunoreactivity of CXCL4 is almost negative in infiltrating mononuclear cells. (H) CD68 staining in a serial section of the cancer lesion. Many CD68+ mononuclear cells are infiltrated.

Apart from immune cells, in one EAOC, CXCL4 was weekly stained in endothelial cells of benign stromal vessels (data not shown). Exudates in endometriosis and dead cell-containing fluid in cancer debris were often stained with CXCL4 (data not shown).

Discussion

A series of investigations have contributed to our understanding of the roles of TAMs in cancer progression, angiogenesis and metastasis.39 TAMs, in concert with cancer cells and other stromal components, mediate chemokine network and contribute to pro-tumoral inflammatory microenvironment. Macrophages are composed of heterogeneous populations, and are currently grouped as M1 (classically activated) and M2 (alternatively activated) phenotypes.40 It is widely accepted that TAMs belong to M2, and they exert pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive properties.39 TAMs may be characterized by some key chemokines such as CCL 17 (TARC) and CCL22 (MDC),39 but it should be noted that the such hallmarks of TAMs depend on tumor types, stages and tissue microenvironments. M2 polarization is determined when circulating immune cells reach to the inflammatory lesion and are consequently activated there. In human ovarian cancers, heterogeneity of infiltrating macrophages in pre-malignant and cancer-related diseases is not fully understood.

In the current study, we have demonstrated that (1) CXCL4 and its variant CXCL4-L1 were suppressed in EAOCs compared with those in endometriosis. (2) In four cases of EAOCs in which cancer developed contiguously from single endometriotic cyst, the expressions of CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 in cancer lesions were at lower levels than those in co-existing endometriosis. (3) The main responsible cell type of CXCL4 expression in benign endometriosis was CD68+ macrophage; on the other hand, CD68+ TAMs lost CXCL4 in cancer area. The cyst wall of endometriosis is diffusely infiltrated by foamy macrophages, and the lesions are periodically inflamed by menstruation for years. When a clear cell or endometrioid cancer arises on the base of endometriosis, these macrophages might differentiate into pro-tumoral phenotype responding to carcinogenic microenvironment and lose CXCL4 in the disease process. Another possibility is that CXCL4 exhaustion might trigger off pro-tumoral property of macrophages and accelerate carcinogenesis. Further investigation is necessary to understand the mechanism of CXCL4 deficiency in TAMs of EAOCs.

We demonstrated previously that the expression of CXCR3B was lower in clear cell cancers than in endometriosis and that the main localization of CXCR3B was in endothelial cells of microvessels.34 Together with the data of current study, impaired CXCL4-CXCR3B axis seems to be involved in differential angiogenic activities between endometriosis and EAOCs. In cancer nests of EAOCs, CXCL4− TAMs may not be able to exert CXCR3B-mediated anti-angiogenesis. CXCL4 is also known to inhibit VEGF and FGF-2 in a direct manner.15,26,27 Therefore, insufficient CXCL4 may allow VEGF/FGF-2-mediated cancer progression. In the microenvironment of ovarian cancers characterized by CXCR3B downregulation34 and increases of VEGF/FGF-2,41,42 CXCL4− TAMs might contribute to cancer development by exploiting several pathways.

CXCL4-L1 variant is known to be a more potent inhibitor than CXCL4 in angiogenesis,35 and in the current study, the expression level of CXCL4-L1 was the highest in endometriosis. This result indicates that CXCL4-L1 may work as an important mediator of anti-angiogenesis in endometriosis. CXCL4-L1 may be produced not only in macrophages but also in some other cell types, and it preferentially diffuses into circulation.29,36 Therefore, we cannot deny the possibility that not only cellular CXCL4-L1 in TAMs but also CXCL4-L1 in fluids are involved in the downregulated CXCL4-L1 in EAOC patients.

In some types of malignancies including ovarian cancers, CC chemokines such as CCL2, CCL5 and CCL22 attract TAMs, or are produced by TAMs, and they induce tumor immune tolerance.43-46 Although the presence of CXCL4 in cultured monocytes and in macrophages of atherosclerosis are reported,29,30 the expression of CXCL4 in macrophages under tumor-associated conditions has not been studied, yet. We investigated the expression of CCL2 in the present cases, but found neither disease specific expression pattern nor significant correlation between CCL2 and CXCL4 (data not shown). It may owe in part that all the present cases except control ovaries have special inflammatory background of endometriosis. Since the role of CXCL4 in macrophage under pathological condition is largely unknown, further studies are required. The current study suggests that the downregulation of CXCL4 in macrophages is associated with disease states of EAOCs and pre-malignant lesions. It should be further investigated the chemokine network involving macrophage-derived CXCL4/CXCL4-L1. It is also the subject for future study to clarify whether CXCL4/CXCL4-L1 can be useful in some clinical settings such as disease markers during the process of EAOC development.

Materials and Methods

Samples

Twenty-four EAOC tissues (13 clear cell and 11 endometrioid types) from the patients who received neither radiotherapy nor neoadjuvant chemotherapies, 18 ovarian endometriosis without malignant components, 4 endometriosis lesions of EAOC cases, and 26 normal ovaries of menopausal and postmenopausal patients with cervical cancers were obtained from surgical specimens of the patients operated at Yokohama City University Hospital (YCUH) and Kanagawa Cancer Center (KCC) between 2002 and 2010. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient, and the experiment design was approved by both Institutional Review Boards (IRB No. A100930005 in YCUH and No. 10 in KCC). Clinical information of the cancer patients is summarized in Table 1. All the cases were reviewed by two pathologists (M. F. and Y. M.), and confirmed that selected cancer ovaries had microscopic endometriosis lesions. These samples were immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen. The remaining tissues were fixed with 10% formalin.

Table 1. Summary of clinical information.

| No. | Histology | Case No. | Age | FIGO stage | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Clear cell |

C0 |

39 |

IIIc |

NED (110) |

| 2 |

Clear cell |

C2 |

54 |

Ia |

NED (98) |

| 3 |

Clear cell |

C3 |

62 |

Ic |

UK (12) |

| 4 |

Clear cell |

C4 |

50 |

IIc |

NED (87) |

| 5 |

Clear cell |

C6 |

42 |

Ia |

NED (82) |

| 6 |

Clear cell |

C14 |

47 |

Ia |

NED (34) |

| 7 |

Clear cell |

C16 |

57 |

Ia |

NED (85) |

| 8 |

Clear cell |

C18 |

57 |

IIIb |

DOD (7) |

| 9 |

Clear cell |

C21 |

56 |

Ic |

NED (45) |

| 10 |

Clear cell |

C26 |

37 |

Ia |

NED (18) |

| 11 |

Clear cell |

C29 |

52 |

Ia |

NED (15) |

| 12 |

Clear cell |

C31 |

46 |

IIIb |

AWD (11) |

| 13 |

Clear cell |

C33 |

63 |

Ic |

NED (4) |

| 14 |

Endometrioid |

D1 |

51 |

IIc |

NED (96) |

| 15 |

Endometrioid |

D5 |

53 |

IIc |

NED (49) |

| 16 |

Endometrioid |

D8 |

52 |

IIc |

NED (36) |

| 17 |

Endometrioid |

D12 |

59 |

Ia |

NED (24) |

| 18 |

Endometrioid |

D13 |

65 |

Ia |

NED (19) |

| 19 |

Endometrioid |

D14 |

58 |

Ia |

NED (18) |

| 20 |

Endometrioid |

D15 |

49 |

Ia |

NED (17) |

| 21 |

Endometrioid |

D16 |

51 |

Ia |

NED (15) |

| 22 |

Endometrioid |

D17 |

62 |

Ia |

NED (11) |

| 23 |

Endometrioid |

D19 |

52 |

Ic |

NED (11) |

| 24 | Endometrioid | D20 | 60 | IIIb | NED (12) |

Abbreviations: FIGO, international federation of gynecology and obstetrics; NED, no evidence of the disease; UK, unknown; DOD, dead of the disease; AWD, alive with the disease. *Gray background indicates that microscopically-confirmed endometriosis lesions are also obtained for comparative study.

RNA isolation

Total RNAs from the frozen tissues were obtained using RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR

The primers of reverse transcriptase-mediated polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to examine the expression levels of human CXCL4 and CXCL4-L1 variant are as follows: forward (F) 5′-TGAAGAATGGAAGGAAAATTTGC-3′ and reverse (R) 5′- CAAATGCACACACGT- AGGCAGCT-3′ for CXCL4 specific primers, (F) 5′- CAGAACCCCAGCCCGACTTTCCC-3′ and (R) 5′-AACGCCAAGAACAGCATCTC-3′ for CXCL4-L1 specific primers, and (F) 5′-CCACCCATGGCAAATTCC-3′ and (R) 5′-TGATGGGATTTCCATTGATGAC-3′ for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).34 Conditions for PCR using Fast cycling PCR kit (QIAGEN) were as follows; at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 5 sec, 68°C for 3 sec, with an extension step of 1 min at 72°C.

QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN) was used for real-time RT-PCR analysis according to the method previously described.34 Conditions for PCR were at 50°C for 2 min, at 95°C for 15 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, at 60°C for 30 sec.

Western blot

The mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) against CXCL4 was purchased from Abcam. Mouse mAb against β-actin was purchased from Sigma. 12.5 μg proteins were subjected to 12.5% gel electrophoresis. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used as the secondary antibody. Isolated platelets were used as the positive control of CXCL4.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse mAbs against CD68, CD8, CD4, CD20 and rabbit mAb against CD3 were purchased from DAKO, and CXCL4 was from Abcam. Working dilution was 1: 200 in CXCL4 and 1:100 in the other antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was done using ENVISION kit (DAKO) with autoclave antigen retrieval technique. Double staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the specimens were incubated with the primary antibody, and then reacted with species-specific biotinylated secondary antibodies, followed by streptavidin-HRP and DAB. After stopping reaction, the specimens were washed thoroughly and incubated with different primary antibody, and then reacted with species-specific biotinylated secondary antibodies, followed by streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase and BCIP/NBT. Lymph nodes were used as positive controls.

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed in Statview 5.0. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical evaluation. When a significant difference was seen, post-hoc test was performed. Statistical significance was assumed when p < 0.05 was obtained.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of Molecular Pathology and Gynecology departments for tissue sampling and discussion, and Mr. T Matsuzawa, Ms. H Soeda and Ms. T Taniguchi for excellent technical assistance. We also thank to bio-bank members of Advanced Medical Center of Yokohama City University and Research and Information Association of Kanagawa Cancer Center. This work is supported by Gants in Aid for Scientific Research (20590363) and Yokohama foundation for advancement of medical science (to MF).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/20084

References

- 1.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matarese G, De Placido G, Nikas Y, Alviggi C. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: natural immunity dysfunction or autoimmune disease? Trends Mol Med. 2003;9:223–8. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sainz de la Cuesta R, Eichhorn JH, Rice LW, Fuller AF, Jr., Nikrui N, Goff BA. Histologic transformation of benign endometriosis to early epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:238–44. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prefumo F, Todeschini F, Fulcheri E, Venturini PL. Epithelial abnormalities in cystic ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:280–4. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern RC, Dash R, Bentley RC, Snyder MJ, Haney AF, Robboy SJ. Malignancy in endometriosis: frequency and comparison of ovarian and extraovarian types. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:133–9. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato N, Tsunoda H, Nishida M, Morishita Y, Takimoto Y, Kubo T, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on 10q23.3 and mutation of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN in benign endometrial cyst of the ovary: possible sequence progression from benign endometrial cyst to endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7052–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, Zhao Y, Tse K, Zeng T, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1532–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:237–45. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vicari AP, Caux C, Trinchieri G. Tumour escape from immune surveillance through dendritic cell inactivation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:33–42. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardini G, Ribatti D, Spinetti G, Morbidelli L, Ziche M, Santoni A, et al. Analysis of the role of chemokines in angiogenesis. J Immunol Methods. 2003;273:83–101. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(02)00420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vicari AP, Caux C. Chemokines in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:143–54. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romagnani P, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Lazzeri E, Beltrame C, Francalanci M, et al. Cell cycle-dependent expression of CXC chemokine receptor 3 by endothelial cells mediates angiostatic activity. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:53–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI9775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bikfalvi A. Recent developments in the inhibition of angiogenesis: examples from studies on platelet factor-4 and the VEGF/VEGFR system. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1017–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauty A, Colvin RA, Wagner L, Rochat S, Spertini F, Luster AD. CXCR3 internalization following T cell-endothelial cell contact: preferential role of IFN-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (CXCL11) J Immunol. 2001;167:7084–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin S, Rottman JB, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, et al. The chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:746–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romagnani P, Beltrame C, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Luconi M, Galli G, et al. Role for interactions between IP-10/Mig and CXCR3 in proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2518–26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kouroumalis A, Nibbs RJ, Aptel H, Wright KL, Kolios G, Ward SG. The chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 differentially stimulate G alpha i-independent signaling and actin responses in human intestinal myofibroblasts. J Immunol. 2005;175:5403–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zipin-Roitman A, Meshel T, Sagi-Assif O, Shalmon B, Avivi C, Pfeffer RM, et al. CXCL10 promotes invasion-related properties in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3396–405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawada K, Sonoshita M, Sakashita H, Takabayashi A, Yamaoka Y, Manabe T, et al. Pivotal role of CXCR3 in melanoma cell metastasis to lymph nodes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4010–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suyama T, Furuya M, Nishiyama M, Kasuya Y, Kimura S, Ichikawa T, et al. Up-regulation of the interferon gamma (IFN-gamma)-inducible chemokines IFN-inducible T-cell alpha chemoattractant and monokine induced by IFN-gamma and of their receptor CXC receptor 3 in human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:258–67. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuya M, Suyama T, Usui H, Kasuya Y, Nishiyama M, Tanaka N, et al. Up-regulation of CXC chemokines and their receptors: implications for proinflammatory microenvironments of ovarian carcinomas and endometriosis. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1676–87. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lasagni L, Francalanci M, Annunziato F, Lazzeri E, Giannini S, Cosmi L, et al. An alternatively spliced variant of CXCR3 mediates the inhibition of endothelial cell growth induced by IP-10, Mig, and I-TAC, and acts as functional receptor for platelet factor 4. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1537–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehlert JE, Addison CA, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. Identification and partial characterization of a variant of human CXCR3 generated by posttranscriptional exon skipping. J Immunol. 2004;173:6234–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perollet C, Han ZC, Savona C, Caen JP, Bikfalvi A. Platelet factor 4 modulates fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) activity and inhibits FGF-2 dimerization. Blood. 1998;91:3289–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jouan V, Canron X, Alemany M, Caen JP, Quentin G, Plouet J, et al. Inhibition of in vitro angiogenesis by platelet factor-4-derived peptides and mechanism of action. Blood. 1999;94:984–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Hundelshausen P, Weber C. Platelets as immune cells: bridging inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2007;100:27–40. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252802.25497.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasagni L, Grepin R, Mazzinghi B, Lazzeri E, Meini C, Sagrinati C, et al. PF-4/CXCL4 and CXCL4L1 exhibit distinct subcellular localization and a differentially regulated mechanism of secretion. Blood. 2007;109:4127–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-052035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitsilos S, Hunt J, Mohler ER, Prabhakar AM, Poncz M, Dawicki J, et al. Platelet factor 4 localization in carotid atherosclerotic plaques: correlation with clinical parameters. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:1112–20. doi: 10.1160/TH03-02-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pervushina O, Scheuerer B, Reiling N, Behnke L, Schröder JM, Kasper B, et al. Platelet factor 4/CXCL4 induces phagocytosis and the generation of reactive oxygen metabolites in mononuclear phagocytes independently of Gi protein activation or intracellular calcium transients. J Immunol. 2004;173:2060–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasper B, Winoto-Morbach S, Mittelstädt J, Brandt E, Schütze S, Petersen F. CXCL4-induced monocyte survival, cytokine expression, and oxygen radical formation is regulated by sphingosine kinase 1. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1162–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen F, Bock L, Flad HD, Brandt E. A chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan on human neutrophils specifically binds platelet factor 4 and is involved in cell activation. J Immunol. 1998;161:4347–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furuya M, Yoneyama T, Miyagi E, Tanaka R, Nagahama K, Miyagi Y, et al. Differential expression patterns of CXCR3 variants and corresponding CXC chemokines in clear cell ovarian cancers and endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:648–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Struyf S, Burdick MD, Proost P, Van Damme J, Strieter RM. Platelets release CXCL4L1, a nonallelic variant of the chemokine platelet factor-4/CXCL4 and potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2004;95:855–7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146674.38319.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubrac A, Quemener C, Lacazette E, Lopez F, Zanibellato C, Wu WG, et al. Functional divergence between 2 chemokines is conferred by single amino acid change. Blood. 2010;116:4703–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbings D, Befus AD. CD4 and CD8: an inside-out coreceptor model for innate immune cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:251–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0109040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popovich PG, van Rooijen N, Hickey WF, Preidis G, McGaughy V. Hematogenous macrophages express CD8 and distribute to regions of lesion cavitation after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2003;182:275–87. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1065–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–55. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obermair A, Speiser P, Reisenberger K, Ullrich R, Czerwenka K, Kaider A, et al. Influence of intratumoral basic fibroblast growth factor concentration on survival in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Lett. 1998;130:69–76. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen GH, Ghazizadeh M, Kawanami O, Shimizu H, Jin E, Araki T, et al. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human ovarian carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:196–203. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Negus RP, Stamp GW, Relf MG, Burke F, Malik ST, Bernasconi S, et al. The detection and localization of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in human ovarian cancer. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2391–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI117933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soria G, Ben-Baruch A. The inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and CCL5 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujimoto H, Sangai T, Ishii G, Ikehara A, Nagashima T, Miyazaki M, et al. Stromal MCP-1 in mammary tumors induces tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and contributes to tumor progression. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1276–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]