Abstract

Comment on: Love IM, et al. Cell Cycle 2012; 11:2458-66

The tumor suppressor protein p53 acts as a guardian of genomic integrity and protects cells against a wide variety of stress conditions. Upon moderate DNA damage or certain stress signals, p53 induces a growth arrest in either G1 or G2 phase of the cell cycle. A key event leading to this growth arrest is the direct transcriptional activation of the cell cycle-dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor p21 by p53.

Previous studies have identified histone acetyltransferase (HAT) proteins assisting p53 in binding to the transcriptional control region of p53 target genes and in creating a chromatin environment, including histone and p53 acetylation, permissive for gene transcription.1-4

Three major groups of HATs have been shown to modify p53 lysine residues located in the central DNA binding domain, its nuclear location signal or its multifunctional C-terminal regulatory domain. The MYST family members TIP60 and hMOF acetylate lysine K120 in the DNA binding domain, an event that controls the ability of p53 to induce transcription-dependent and -independent apoptosis.5-7 GNAT family members PCAF and GCN5 primarily acetylate K320 in the nuclear location signal of p53. This modification occurs after DNA damage and contributes to the stabilization of p53 and enhances its ability to bind DNA.2,3,8 The third group of HATs, p300 and CBP, modifies several lysine residues in the C terminus, including K373 and K382, and K164 in the DNA binding domain.1,3,4 Acetylation by p300/CBP stimulates high affinity DNA binding of p531,2 and shields it from the repressive function of mdm2.4

An important question is to what extent histone acetylation, occurring sequentially or in parallel to p53 acetylation, contributes to target gene activation. The manuscript by Love et al. in a recent issue of Cell Cycle addresses this question for PCAF in the context of the p21 promoter.8 Using siRNA-mediated knockdown of PCAF, the authors show that the p21 gene is no longer inducible by p14ARF expression in either U2OS osteosarcoma or diploid RPE1 cells. By contrast, interference with p300 or CBP expression led to p53 stabilization and increased levels of constitutevly expressed p21 protein in both cell types. Therefore, PCAF function is essential for inducible expression of p21, while p300 and CBP appear to negatively regulate p21 expression in the absence of a stimulus, perhaps due to their ability to promote p53 ubiquitylation and degradation.

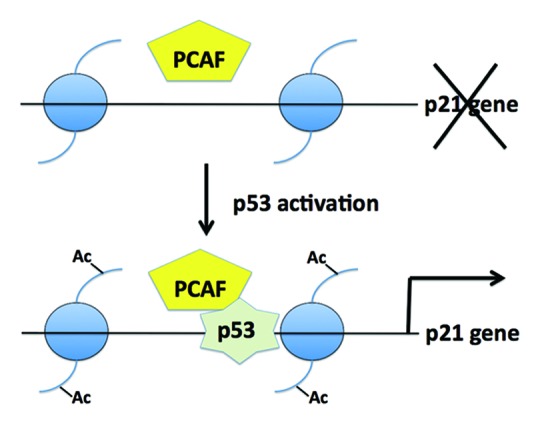

As a functional consequence of PCAF siRNA treatment, cells fail to arrest the cell cycle in response to p14ARF expression or treatment with nutlin3a, an inhibitor of the p53-mdm2 interaction.8 Acetylation of p53 K320 by PCAF is not required for p21 gene induction, since a mutant p53 carrying a K(319–321)R substitution was fully capable of inducing p21. These findings raised the possibility that the critical substrates for PCAF acetylation were in fact the nucleosomal histones bound to the p21 promoter. Indeed, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments performed by Love et al. showed that acetylation of histone H3 K9 and K14 was increased upon p53 activation, an effect that required the presence of enzymatically active PCAF.8 These two histone H3 residues were previously demonstrated to be the preferred histone substrates of PCAF. The authors also showed that p53 is recruited in vivo to the distal p53 response element of the p21 promoter following doxorubicin treatment, while PCAF was constitutively present at that region (Fig. 1).8

Figure 1. PCAF appears to be present constitutively at the p21 promoter. Top of the panel, in the absence of a stimulus, PCAF cannot acetylate histones in the promoter bound nucleosomes (blue). Upon activating signals, p53 binds to the p21 promoter, triggering PCAF-dependent histone H3 acetylation and expression of the p21 gene, see bottom part of Figure.

Taken together, the results of Love et al. reveal that PCAF acts as a true HAT, acetylating two lysine residues in the histone H3 tail of nucleosomes at the p21 promoter in response to a diverse array of stimuli leading to p53 activation.

No matter whether genotoxic or non‑genotoxic stimuli were used, PCAF was always required for full inducible expression of p21. By contrast, p300 or CBP were not required for p21 stimulation, but rather appeared to repress basal p21 levels. A recent study by Kasper et al. showed that both p21 and mdm2 expression was inducible in cells double null for p300 and CBP in response to etoposide or doxorubicin.9 Interestingly, basal levels of p21 and mdm2 were also slightly increased in the absence of p300 and CBP, although not as much as in the study by Love et al.8 Thus, two independent reports agree that p300 and CBP are dispensable for p53-dependent activation of p21.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21235

References

- 1.Gu W, et al. Cell. 1997;90:595–606. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi K, et al. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1202–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y, et al. Cell. 2008;133:612–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Y, et al. Mol Cell. 2008;24:827–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knights CD, et al. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:533–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sykes SM, et al. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20197–205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Love IM, et al. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2458–66. doi: 10.4161/cc.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasper LH, et al. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:212–21. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.2.14542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]