Abstract

Progression through the eukaryotic cell division cycle is governed by the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). For a CDK to become active it must (1) bind a positive regulatory subunit (cyclin) and (2) be phosphorylated on its activation (T) loop. In metazoans, multiple CDK catalytic subunits, each with a distinct set of preferred cyclin partners, regulate the cell cycle, but it has been difficult to assign functions to individual CDKs in vivo. Biochemical analyses and experiments with dominant-negative alleles suggested that specific CDK/cyclin complexes regulate different events, but genetic loss of interphase CDKs (Cdk2, -4 and -6), alone or in combination, did not block proliferation of cells in culture. These knockout and knockdown studies suggested redundancy or plasticity built into the CDK network but did not address whether there was true redundancy in normal cells with a full complement of CDKs. Here, we discuss recent work that took a chemical-genetic approach to reveal that the activity of a genetically non-essential CDK, Cdk2, is required for cell proliferation when normal cyclin pairing is maintained. These results have implications for the systems-level organization of the cell cycle, for regulation of the restriction point and G₁/S transition and for efforts to target Cdk2 therapeutically in human cancers.

Keywords: Cdk2, DNA synthesis (S) phase, analog-sensitive (AS) kinase, cancer drug discovery, cell cycle, chemical genetics, cyclin, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), restriction point

Introduction

In eukaryotes, CDK activity is required for progression through the cell cycle and increases from a minimum in early G1 to a peak during mitosis.1 Budding and fission yeast each have a single CDK that regulates passage through both the G1/S and G2/M transitions by binding to multiple cyclin partners that are sequentially expressed and that affect activity, substrate specificity and responsiveness to regulators in distinct ways.2-4 In contrast, metazoans have multiple CDKs that bind specific cyclins to become activated in a precise temporal order.1,5,6 Based on activation timing, apparent CDK-cyclin binding preferences and sensitivity to different regulators, a model of the metazoan cell cycle emerged in which Cdk4 and Cdk6 bind cyclin D to control G1; Cdk2 binds cyclins E and A to regulate the G1/S transition and S phase, and Cdk1 binds cyclins A and B to regulate G2 and mitosis. The defined order of activation suggested that different CDKs might be required for different cell cycle events, but studies aimed at understanding the roles of individual CDKs yielded conflicting results.

This question was first investigated by microinjection of antibodies specific for individual CDKs or cyclins. Different antibodies caused discrete cell cycle arrests during G1 (Cdk2, or cyclins E or A) or G2 (cyclin A), suggesting distinct but overlapping functions of the various complexes.7-9 In addition, overexpression of dominant-negative (DN) Cdk alleles in mammalian cells suggested that Cdk1 and Cdk2 regulate different stages or processes in the cell cycle. The variants expressed in these studies were catalytically inactive CDKs that retained their ability to bind cyclins. Because DN CDKs are presumed to exert their effects in vivo by preventing cyclins from binding endogenous CDKs, these variants should affect cell cycle progression only when expressed at levels high enough to out-compete wild-type CDKs. This represents a potential pitfall of the method: changing intracellular CDK concentrations could result in the formation of CDK/cyclin complexes that do not exist in wild-type cells. Despite this caveat, expression of Cdk1-DN blocked human cells at the G2/M transition, consistent with the arrest points observed with conditional Cdk1 knockouts in mammalian cells,10 temperature-sensitive Cdk1 mutations in Drosophila11,12 and selective small-molecule inhibition of Cdk1 in avian cells.13 The situation for Cdk2 was less clear; Cdk2-DN caused arrests in G1, S or G2 depending on expression level and cell type14,15 and had little or no effect in certain human cancer cells, such as colon carcinoma.16

Making do with Less: The Birth of Cell Cycle Minimalism

The “classical” model, in which the sequential activity of different CDK/cyclin complexes is needed for passage through the major transitions of the cell cycle, was challenged when knockdown of Cdk2 with antisense DNA or small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides failed to block proliferation or cause a G1 arrest in a variety of human cell lines.16 Subsequently, gene disruptions in mice demonstrated that Cdk2 is dispensable for viability and cell proliferation, although it is required for meiosis.17,18 Parallel studies demonstrated that neither Cdk419,20 nor Cdk621 is absolutely required for proliferation, but that tissue-specific defects occur in the absence of either CDK. In fact, cells can proliferate in culture, albeit at a reduced rate, without any of the “interphase” CDKs (i.e., Cdk2, -3, -4 and -6), and Cdk2-/- Cdk4-/- Cdk6-/- mice (of a strain that naturally lacks Cdk3) can develop until mid-gestation before dying, probably due to hematopoietic failure.22 The defects observed in various Cdk-null mice suggested that, whereas Cdk1 is the only CDK strictly essential for mammalian cell division, some specialized functions of interphase CDKs might be required in specific tissues or for optimal coordination of cell division with other cellular processes.

The Cdk-knockout studies suggest redundancy and/or plasticity within the CDK network, which might arise in one of two ways. First, multiple CDKs normally regulate the same process, but only one is required. For example, genetic evidence suggests that the activities of Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk4/cyclin D are likely to converge on a common set of G1 regulators (the pocket proteins, consisting of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein RB and its paralogs; and the E2F family of transcription factors, which are targets of regulation by the pocket proteins). Although neither Cdk2 nor Cdk4 is required for mouse viability, the knockout of both genes results in embryonic lethality.23 Furthermore, Cdk2 knockdown in cyclin D-null cells blocks proliferation and cell cycle re-entry, whereas either perturbation alone has minimal effects.24 In addition, the tissue-specific effects of cyclin D1 loss can be rescued by expression of cyclin E1 from the cyclin D1 locus, suggesting that either cyclin E- or cyclin D-dependent kinase activity can trigger some of the same events.25

A second form of compensation occurs when the ablation of a CDK results in rewiring of the cell cycle circuitry. The ability of certain Cdk-knockout cells to proliferate is likely to be due to: (1) expanded functions of natural CDK/cyclin complexes and (2) the formation (and function) of non-canonical CDK-cyclin pairs.22,26 This phenomenon was first described in Cdk2-/- cells, in which Cdk1 binds cyclin E, apparently to regulate onset of S phase. This led to the hypothesis that Cdk1 might be an important physiologic regulator of S-phase entry, even though Cdk1/cyclin E complexes are nearly undetectable in wild-type cells.26 Some of the atypical complexes detected in the mutants (e.g., Cdk1/cyclin E and Cdk1/cyclin D) do not readily form in vitro,27 so it is unclear how these proteins can stably associate in vivo. Results such as these have nonetheless been interpreted to support a new model of cell cycle control, in which Cdk1 is a central regulator of both the G1/S and G2/M transitions. The implicit assumption that these non-canonical CDK/cyclin complexes exist normally has not been rigorously tested.28 Because CDK/cyclin complexes are frequently misregulated in cancer cells, they are the focus of intense drug discovery efforts; distinguishing between the two models of cell cycle control—classical vs. “minimal”—is important if we are to choose the “right” targets for those drugs.

Following the Path of Least Resistance: Distinct Activation Pathways Give Cdk2 Priority over Cdk1 for Cyclin Binding

To assess the specificity of CDK-cyclin pairing in human cells, we determined the relative amounts of Cdk1 and Cdk2 bound to cyclins throughout the cell cycle and showed that: (1) cyclin E is bound nearly exclusively to Cdk2; (2) cyclin B binds only to Cdk1; and (3) cyclin A preferentially forms complexes with Cdk2 until mid- to late-S phase, when Cdk1/cyclin A complexes begin to appear. This was the case in two different human cell lines we tested: K562 leukemic cells and HCT116 colon carcinoma cells,6 which were previously shown to be resistant to Cdk2 knockdown and Cdk2-DN overexpression.16 Therefore, in cells with a full complement of CDKs, Cdk1 remains in a predominantly cyclin-free state until after S phase has already begun and thus seemed an unlikely candidate to regulate early cell cycle events.

The cyclin A-binding priority of Cdk2, which is ~10-fold less abundant than Cdk1 in mammalian cells, implies that Cdk2 has evolved a non-catalytic “scaffold” function that excludes Cdk1 from complexes with cyclin A and thus prevents premature Cdk1 activation (Fig. 1). This competitive advantage depends in part on how different CDK/cyclin complexes form. To become active, a CDK must (1) bind cyclin and (2) be phosphorylated on its T loop by a CDK-activating kinase (CAK). In metazoans, the only known CAK is itself a CDK, Cdk7.29-31 Despite sharing an activating kinase, a cyclin partner and ~65% amino-acid sequence identity, Cdk1 and Cdk2 follow distinct paths to activation in vivo, in part due to the way they are recognized by Cdk7.5,6 Cdk2 can follow either of two pathways: a primary, phosphorylation-first mechanism, in which it is first modified by Cdk7 and then binds cyclin; or a secondary pathway, in which it binds cyclin prior to phosphorylation.6 Cdk1, on the other hand, must be cyclin-bound for Cdk7 to recognize it as a substrate.30 In the absence of T-loop phosphorylation, moreover, Cdk1/cyclin complexes are unstable, suggesting that the two steps of Cdk1 activation must occur in concert.29 Mathematical modeling, validated by biochemical experiments, suggests that a kinetically more favorable pathway of activation could suffice to make Cdk2 the preferred partner of cyclin A.5,6,32 In addition, any Cdk1/cyclin A complexes that do form are phosphorylated at Tyr15 and thereby kept inactive until late S phase, depending on the checkpoint kinase Chk1.33 Therefore, the order of CDK activation is enforced by multiple mechanisms, suggesting that it is an important regulatory feature of the mammalian cell cycle.

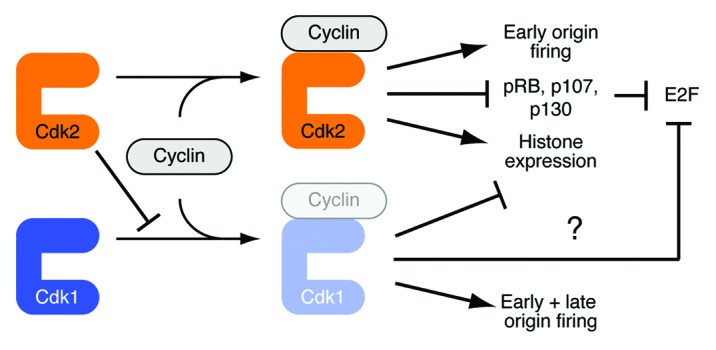

Figure 1. Catalytic and non-catalytic functions of Cdk2 coordinate S phase events Cdk2’s priority in cyclin binding inhibits the formation of Cdk1-cyclin complexes during G1 and early S phase of the cell cycle. This ordering of CDK activation, conferred by a non-catalytic function of Cdk2, makes Cdk2 activity essential for R-point passage and early S phase. By mid- to late-S phase Cdk2 no longer inhibits Cdk1-cyclin binding (perhaps because the concentration of free Cdk2 has dropped), and active Cdk1 promotes late S-phase events, such as firing of late origins,33 inhibition of histone synthesis34 and, possibly, shutting down of E2F-dependent transcription.47 Therefore, the precise timing of CDK activation ensures the proper ordering of cell-cycle events.

Why More (CDKs) Might be Better

A priori, there are two possible reasons why reinforcing mechanisms might have evolved to delay both assembly and activation of Cdk1/cyclin A complexes until mid- or late-S phase, which are not mutually exclusive (Fig. 1). First, Cdk2 might be specifically adapted to control events of late G1 and early S phase. Second, Cdk1/cyclin A might have unique functions that need to be restrained until later in the cell cycle. One such function, temporal regulation of the S-phase replication program, was revealed by the same study that showed premature Cdk1/cyclin A activation upon ablation of Chk1; in Chk1-deficient cells, or in cells forced to express a constitutively active Cdk1-cyclin A2 fusion refractory to inhibitory phosphorylation (and thus to Chk1), the normal order of replication origin-firing was disrupted.33 Uncoordinated origin-firing might cause replication stress and threaten genome integrity. So too might another specialized function of Cdk1/cyclin A if activated ahead of schedule: the repression of histone synthesis, by degradation of the stem-loop binding protein specifically needed for histone mRNA 3'-end maturation, which normally occurs only at the end of S phase.34

Cdk2 Activity is Required for Proliferation of Normal and Cancer Cells

Although results in Cdk-null cells and animals indicated that Cdk1 is sufficient for proliferation, biochemical analyses suggest that it is unlikely to regulate the G1/S transition in wild-type cells with a full set of CDKs. This raised the possibility that a genetically non-essential CDK, Cdk2, might perform essential catalytic functions in vivo when its non-catalytic scaffold function is preserved. Because available inhibitors are only moderately selective for Cdk2 over other CDKs, we used a chemical-genetic approach to determine if Cdk2 activity is essential when normal CDK-cyclin pairings are maintained. Mutating the bulky “gatekeeper” residue in the ATP-binding pocket of Cdk2 to Gly confers sensitivity to pyrazolopyrimidine-based analogs such as 3-MB-PP1 that do not affect wild-type kinases, thereby providing a way to inhibit Cdk2 specifically. We targeted the Cdk2 locus in transformed (HCT116 colon carcinoma) and non-transformed (telomerase-expressing retinal pigment epithelial RPE-hTERT) cells for homologous gene replacement to “knock in” an analog-sensitive (AS) allele, Cdk2F80G. After two rounds of gene targeting, we obtained cells that expressed only Cdk2as, at wild-type levels, from the endogenous locus.32

This allowed us to demonstrate that Cdk2 activity is required for proliferation in both non-transformed and cancer cells.32 In addition to homozygous Cdk2as/ as cells, we examined two other genotypes: Cdk2as/+, in which Cdk2 is expressed at wild-type levels, but only ~half of it is 3-MB-PP1-sensitive; and Cdk2as/ neo, in which only about half the normal amount of Cdk2 is expressed (the neomycin-resistance cassette used for selection during gene targeting causes silencing of the genomic locus unless it is excised), but all of it is sensitive to the drug. This allelic series revealed that drug sensitivity was gene dosage-dependent, and that cells expressing AS Cdk2 at half the wild-type level were equally sensitive whether or not they retained an expressed, wild-type copy of Cdk2 (as/as > as/neo ~ as/+ > +/+). Therefore, inhibition of the AS fraction of Cdk2 in as/+ cells caused slowing of proliferation to the same extent as did inhibition of Cdk2as in as/neo cells, where another CDK such as Cdk1 can compensate for the 50% reduction in Cdk2 levels. Both chemical inhibition and normal expression levels of Cdk2as were necessary to achieve a near-complete block of proliferation. In addition, Cdk2-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) engineered to overexpress Cdk2as were even more sensitive to the drug than the human cells with normal levels of Cdk2as, possibly because the elevated levels of Cdk2as disrupted normal Cdk1-cyclin pairing and increased dependency on Cdk2. From these results, we conclude that activity of Cdk2 is essential when its scaffold function is preserved and it is therefore the preferred partner of cyclins E and A, but not when Cdk2 protein levels are lowered by gene disruption or RNA interference (RNAi). Indeed, diminished AS kinase expression protected cells from growth impairment by an allele-specific inhibitor—a clear case of non-equivalence between knockout- (or RNAi-) and small molecule-based approaches.

Providing Safe Passage: Cdk2 Drives Cells through the R Point and G1/S

Cdk2 was first proposed to be an essential regulator of S phase based on its activation timing, cyclin-binding preferences and DN phenotypes, but this argument appeared to be refuted by results of Cdk2 gene disruption and RNAi. Loss of Cdk2 protein did not arrest cells in G1, suggesting a previously unappreciated role for Cdk1 in controlling S-phase entry. These results are consistent with two different scenarios: (1) Cdk1 and Cdk2 are both regulators of S-phase entry in wild-type cells or (2) Cdk1 only assumes this role when it gains the ability to bind cyclin E in the absence of Cdk2. Even if Cdk1 does perform this function in wild-type cells, it is unlikely to do so exclusively; in chicken, DT40 cells engineered to express AS Cdk1, Cdk1 activity were required for DNA replication only when Cdk2 was deleted.13 In Cdk2as/as cells, Cdk2 inhibition impaired S-phase entry after release from G0, and the requirement for Cdk2 activity became more stringent when growth factors were limiting. In addition, Cdk2 is a non-redundant, rate-limiting regulator of passage through the restriction (R) point, when continued cell cycle progression becomes mitogen-independent.32

The mechanisms by which Cdk2 promotes R-point passage and S-phase entry remain unknown but are likely to be mediated in part through the E2F-dependent transcription program. Cdk2 activity was required for normal timing of phosphorylation of the pocket proteins RB, p107 and p130, and this requirement was more stringent when cells were grown in low concentrations of serum (≤ 2.5%). This correlated with a greater dependence of proliferation and S-phase entry on Cdk2 activity when growth factors were limiting.32 Cdk2 is unlikely to play a direct role in turning on the E2F program; a recent reexamination of microarray data from HeLa cell synchronization-and-release experiments suggested that initial transcription of the genes responsible for positive feedback in the E2F transcription network, including cyclin E1 and cyclin E2, occurs concomitant with expression of E2F1 itself.35 Instead, the role of Cdk2 might be analogous to that of a Cdk1/Cln1,2-dependent positive-feedback loop that regulates the G1/S transcription program in budding yeast.36 In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two related transcription factors, SBF and MBF, function analogously to metazoan E2Fs and are negatively regulated by Whi5, the analog of RB.37,38 Expression of SBF/MBF-dependent genes is inhibited during G1 by Whi5, and this repression is partially relieved when Whi5 is phosphorylated by Cdk1/Cln3. This allows expression of SBF/MBF target genes CLN1 and CLN2, thereby establishing a positive feedback loop via Cdk1/Cln1,2-dependent Whi5 phosphorylation. This feedback appears to be important for coherence of the SBF/MBF regulon: the coordinated timing of initial induction, peak transcript level and shutdown of the genes regulated by these factors. Loss of this coordination in cln1Δ cln2Δ cells resulted in increased frequency of cell cycle arrest, indicating the importance of coherent gene expression for cell fitness and survival.36 Determining whether mammalian Cdk2 regulates the E2F program in an analogous fashion—or through a distinct mechanism—will be important for understanding its functions in R-point and S-phase control. It will also be a test of Cdk2’s potential value as an anticancer drug target, discussed in the next section.

A Dose of Reality: Targeting the Physiologic CDK Network with Small Molecules in Cancer

Understanding the organizing principles of the mammalian cell cycle has implications for efforts to target CDKs in cancer. CDK inhibitors have been suggested and tested as anticancer therapeutic agents, but Cdk-knockout studies raised questions regarding the utility of targeting “non-essential” CDKs. Cyclins and regulators of CDK activity are frequently mutated or misregulated in tumors, and many of these aberrations result in cell proliferation, partly independent of extracellular cues.1 In some instances, this is due to hyperactivation of growth factor signaling pathways, but in others, there is a more direct effect on the CDK regulatory network (reviewed in ref. 39). Expression of cyclin D or E, for example, is frequently increased in cancer cells, whereas the levels of CDK inhibitor proteins (CKIs) are often repressed. These changes can lead to premature activation of G1-phase CDKs and a lowered threshold of mitogenic signaling required for cell cycle entry, probably due to the inappropriate inactivation of RB-family proteins.40,41 Expression of these cell cycle regulators, including cyclin E, can be used to grade and classify tumors, consistent with connections between clinical outcome and the activity or integrity of the CDK network.

In some instances derangement of the cell cycle is not merely a consequence of transformation but a prerequisite for continued proliferation of cancer cells. One study that illustrates this point investigated how breast cancers develop resistance to inhibitors to the growth factor receptor HER2 after prolonged drug treatment.42 That resistance was conferred by amplification of the cyclin E locus; cyclin E knockdown or CDK inhibition impaired proliferation to a greater extent in patient-derived cells that were resistant to the HER2 inhibitor than in naïve cells, and cyclin E overexpression caused naïve cells to acquire resistance to the HER2 inhibitor. Patient data corroborated this interaction—individuals with low or normal levels of cyclin E responded to treatment with the HER2 inhibitor better than did those with cyclin E amplification or overexpression.

This and other studies suggest that inhibition of CDKs, and specifically of Cdk2 (the exclusive partner of cyclin E in wild-type cells),6 might be effective in treating tumors of specific genotypes. It remains to be determined if general CDK inhibitors will be clinically useful, or if toxicity to normal tissue will limit their efficacy. We have shown that Cdk2 activity is required for proliferation of both transformed and non-transformed cells in culture.32 Cancer cells might have increased requirements for Cdk2 activity, however, as suggested by the ability of inhibitory analogs to impede anchorage-independent growth of Cdk2as/as HCT116 cells and of Cdk2-/- MEFs overexpressing Cdk2as after transformation by multiple oncogenes.43 Moreover, Cdk2 might be a potential target for “synthetic lethal” chemotherapy, which exploits vulnerability to DNA damage—either caused by intrinsic mutations or induced by drugs—in cancer cells.44 The availability of both transformed (HCT116) and non-transformed (RPE-hTERT) Cdk2as/as human cell lines can potentially serve as a guide for developing cancer-specific treatments, even though the cells do not originate from the same tissue.

Whether truly specific inhibitors can be developed for individual CDKs remains an unanswered question. Currently available inhibitors are moderately selective at best and typically affect both cell cycle and transcriptional CDKs. This promiscuity has been blamed for the toxicity of these drugs in early clinical trials.28 Nearly all CDK inhibitors are ATP-competitive, and the ATP-binding pocket is highly conserved across the family, with only subtle structural variations that can be exploited to achieve isoform specificity. Any selectivity that does occur is usually dictated by CDK-drug interactions outside the ATP-binding site, and computer modeling based on that principle has aided in the development of compounds that are more specific for a selected CDK.45,46 In one such study, the more specific inhibitor was less cytotoxic than the less specific one on which it was based, even though the IC50 for the primary target, Cdk9, was the same for both compounds in vitro.45 Therefore, developing specific CDK inhibitors and identifying the situations in which they will be effective—be it a specific genotype, cancer or combination with other agents—could lead to more potent and less toxic treatment regimens.

The AS kinase approach in human cells expressing all cell cycle players at physiologic levels provides a model system for evaluating the effects of single-CDK inhibition on proliferation, survival and genomic integrity. It has also yielded key insights into the organization of the CDK network and revealed non-catalytic functions and other network features that might be targeted by drugs. For example, the ability of Cdk2 to out-compete Cdk1 for binding to cyclin A was compromised by the AS mutation in the absence of analogs but restored by 3-MB-PP1 or a non-inhibitory analog, 6-benzyl-aminopurine, 6-BAP.32 This suggests that specificity of CDK-cyclin pairing, not merely the activity of the resulting complexes, might be manipulated with small molecules, perhaps to therapeutic advantage. Finally, the distinct activation pathways of different CDKs in human cells6,29 might present unique opportunities for therapeutic intervention, with a better chance of achieving CDK specificity while sparing functions needed in non-dividing cells. For example, phosphorylation of monomeric Cdk2 by Cdk7 might be targeted with novel compounds, not necessarily directed at the active site of either kinase.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Fisher lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM056985 to R.P.F.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/20758

References

- 1.Morgan DO. The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control. London: New Science Press Ltd, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loog M, Morgan DO. Cyclin specificity in the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase substrates. Nature. 2005;434:104–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kõivomägi M, Valk E, Venta R, Iofik A, Lepiku M, Morgan DO, et al. Dynamics of Cdk1 substrate specificity during the cell cycle. Mol Cell. 2011;42:610–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom J, Cross FR. Multiple levels of cyclin specificity in cell-cycle control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:149–60. doi: 10.1038/nrm2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merrick KA, Fisher RP. Putting one step before the other: distinct activation pathways for Cdk1 and Cdk2 bring order to the mammalian cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:706–14. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merrick KA, Larochelle S, Zhang C, Allen JJ, Shokat KM, Fisher RP. Distinct activation pathways confer cyclin-binding specificity on Cdk1 and Cdk2 in human cells. Mol Cell. 2008;32:662–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtsubo M, Theodoras AM, Schumacher J, Roberts JM, Pagano M. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2612–24. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–71. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai L-H, Lees E, Faha B, Harlow E, Riabowol K. The cdk2 kinase is required for the G1-to-S transition in mammalian cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:1593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itzhaki JE, Gilbert CS, Porter AC. Construction by gene targeting in human cells of a “conditional’ CDC2 mutant that rereplicates its DNA. Nat Genet. 1997;15:258–65. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigrist S, Ried G, Lehner CF. Dmcdc2 kinase is required for both meiotic divisions during Drosophila spermatogenesis and is activated by the Twine/cdc25 phosphatase. Mech Dev. 1995;53:247–60. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larochelle S, Pandur J, Fisher RP, Salz HK, Suter B. Cdk7 is essential for mitosis and for in vivo Cdk-activating kinase activity. Genes Dev. 1998;12:370–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochegger H, Dejsuphong D, Sonoda E, Saberi A, Rajendra E, Kirk J, et al. An essential role for Cdk1 in S phase control is revealed via chemical genetics in vertebrate cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:257–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Heuvel S, Harlow E. Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science. 1993;262:2050–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8266103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu B, Mitra J, van den Heuvel S, Enders GH. S and G2 phase roles for Cdk2 revealed by inducible expression of a dominant-negative mutant in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2755–66. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2755-2766.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Proliferation of cancer cells despite CDK2 inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:233–45. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berthet C, Aleem E, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Kaldis P. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1775–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortega S, Prieto I, Odajima J, Martín A, Dubus P, Sotillo R, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rane SG, Dubus P, Mettus RV, Galbreath EJ, Boden G, Reddy EP, et al. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in beta-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat Genet. 1999;22:44–52. doi: 10.1038/8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutsui T, Hesabi B, Moons DS, Pandolfi PP, Hansel KS, Koff A, et al. Targeted disruption of CDK4 delays cell cycle entry with enhanced p27(Kip1) activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7011–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malumbres M, Sotillo R, Santamaría D, Galán J, Cerezo A, Ortega S, et al. Mammalian cells cycle without the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6. Cell. 2004;118:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santamaría D, Barrière C, Cerqueira A, Hunt S, Tardy C, Newton K, et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448:811–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berthet C, Klarmann KD, Hilton MB, Suh HC, Keller JR, Kiyokawa H, et al. Combined loss of Cdk2 and Cdk4 results in embryonic lethality and Rb hypophosphorylation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:563–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozar K, Ciemerych MA, Rebel VI, Shigematsu H, Zagozdzon A, Sicinska E, et al. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-cyclins. Cell. 2004;118:477–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geng Y, Whoriskey W, Park MY, Bronson RT, Medema RH, Li T, et al. Rescue of cyclin D1 deficiency by knockin cyclin E. Cell. 1999;97:767–77. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aleem E, Kiyokawa H, Kaldis P. Cdc2-cyclin E complexes regulate the G1/S phase transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:831–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai D, Wessling HC, Fisher RP, Morgan DO. Effects of phosphorylation by CAK on cyclin binding by CDC2 and CDK2. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:345–50. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larochelle S, Merrick KA, Terret ME, Wohlbold L, Barboza NM, Zhang C, et al. Requirements for Cdk7 in the assembly of Cdk1/cyclin B and activation of Cdk2 revealed by chemical genetics in human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;25:839–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher RP, Morgan DO. A novel cyclin associates with MO15/CDK7 to form the CDK-activating kinase. Cell. 1994;78:713–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mäkelä TP, Tassan J-P, Nigg EA, Frutiger S, Hughes GJ, Weinberg RA. A cyclin associated with the CDK-activating kinase MO15. Nature. 1994;371:254–7. doi: 10.1038/371254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merrick KA, Wohlbold L, Zhang C, Allen JJ, Horiuchi D, Huskey NE, et al. Switching Cdk2 on or off with small molecules to reveal requirements in human cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2011;42:624–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsuno Y, Suzuki A, Sugimura K, Okumura K, Zineldeen DH, Shimada M, et al. Cyclin A-Cdk1 regulates the origin firing program in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2009;106:3184–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809350106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koseoglu MM, Graves LM, Marzluff WF. Phosphorylation of threonine 61 by cyclin a/Cdk1 triggers degradation of stem-loop binding protein at the end of S phase. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4469–79. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01416-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eser U, Falleur-Fettig M, Johnson A, Skotheim JM. Commitment to a cellular transition precedes genome-wide transcriptional change. Mol Cell. 2011;43:515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skotheim JM, Di Talia S, Siggia ED, Cross FR. Positive feedback of G1 cyclins ensures coherent cell cycle entry. Nature. 2008;454:291–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Bruin RA, McDonald WH, Kalashnikova TI, Yates J, 3rd, Wittenberg C. Cln3 activates G1-specific transcription via phosphorylation of the SBF bound repressor Whi5. Cell. 2004;117:887–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costanzo M, Nishikawa JL, Tang X, Millman JS, Schub O, Breitkreuz K, et al. CDK activity antagonizes Whi5, an inhibitor of G1/S transcription in yeast. Cell. 2004;117:899–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. To cycle or not to cycle: a critical decision in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:222–31. doi: 10.1038/35106065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:785–97. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knudsen ES, Knudsen KE. Tailoring to RB: tumour suppressor status and therapeutic response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:714–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scaltriti M, Eichhorn PJ, Cortés J, Prudkin L, Aura C, Jiménez J, et al. Cyclin E amplification/overexpression is a mechanism of trastuzumab resistance in HER2+ breast cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2011;108:3761–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014835108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horiuchi D, E Huskey N, Kusdra L, Wohlbold L, Merrick KA, Zhang C, et al. Chemical-genetic analysis of cyclin dependent kinase 2 function reveals an important role in cellular transformation by multiple oncogenic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2012;109:E1019–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111317109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson N, Shapiro GI. Cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) and the DNA damage response: rationale for cdk inhibitor-chemotherapy combinations as an anticancer strategy for solid tumors. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:1199–212. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.525221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali A, Ghosh A, Nathans RS, Sharova N, O’Brien S, Cao H, et al. Identification of flavopiridol analogues that selectively inhibit positive transcription elongation factor (P-TEFb) and block HIV-1 replication. Chembiochem. 2009;10:2072–80. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali S, Heathcote DA, Kroll SH, Jogalekar AS, Scheiper B, Patel H, et al. The development of a selective cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that shows antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6208–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koseoglu MM, Dong J, Marzluff WF. Coordinate regulation of histone mRNA metabolism and DNA replication: cyclin A/cdk1 is involved in inactivation of histone mRNA metabolism and DNA replication at the end of S phase. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3857–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.19.13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]