Abstract

Since the discovery of miRNAs, a number of miRNAs have been identified as p53’s transcriptional targets. Most of them are involved in regulation of the known p53 functions, such as cell cycle, apoptosis and senescence. Our recent study revealed miR-1246 as a novel target of p53 and its analogs p63 and p73 to suppress the expression of DYRK1A and consequently activate NFAT, both of which are associated with Down syndrome and possibly with tumorigenesis. This finding suggests that miR-1246 might serve as a likely link of the p53 family with Down syndrome. Here, we provide some prospective views on the potential role of the p53 family in Down syndrome via miR-1246 and propose a new p53-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT pathway in cancer.

Keywords: DYRK1A, Down syndrome, NFAT, cancer, miR-1246, p53, tumorigenesis

Introduction

The p53 tumor suppressor plays a crucially important role in preventing neoplasia and tumor progression, and its family members, p63 and p73, are also involved in tissue-specific, such as epithelial, central nerve and immune, development,1-3 as p53-knockout mice developed most normally, while p63- or p73-knockout mice were postnatally lethal due to severe defects in epidermal tissues, central neuron and immune systems, respectively.1-4 Despite their distinct biological roles in animal development, the p53 family members do share anticancer activity by regulating the expression of a similar set of target genes at a transcriptional level. Through these target genes, they modulate several essential cellular events, including cell cycle, apoptosis, autophagy and senescence.5 Some of their target genes encode miRNAs instead of proteins.6 These miRNAs have also been shown to play a role in controlling cell growth, apoptosis, senescence and autophagy in a p53-dependent fashion (Table 1).7-20 Recently, we identified miR-1246 as another novel p53 target miRNA. Interestingly, this miRNA regulates the expression of DYRK1A, a Down syndrome-associated kinase,21 which inactivates a nuclear transcriptional factor called NFAT1C by phosphorylating it and preventing it from nuclear import.20 In this review, we will offer some prospective views on this new finding as well as the likely link of p53 or the p53 family with Down syndrome and also propose a new p53 pathway involving miR-1246, DYRK1A and NFAT1c potentially critical for cancer prevention.

Table 1. List of the so far identified p53 targeting miRNAs.

| miRNA(s) | Definition/function | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| miR-34 |

p53 tumor suppressor network; control of cell proliferation promotes apoptosis |

7–9 |

| miR-192 |

cell cycle |

10 |

| miR-194 |

cell cycle |

10 |

| miR-215 |

cell cycle |

10 |

| miR-145 |

control of cell proliferation; target c-Myc |

11 |

| miR-17–92 cluster |

apoptosis |

12 |

| miR-107 |

cell cycle; target CDK6 and p130 |

13 |

| miR-149* |

oncogenic regulator |

14 |

| miR-200 |

unknown |

15 |

| miR-210 |

cytoprotective effects |

16 |

| miR-335 |

stress response; target Rb1 (pRb/p105) |

17 |

| miR-605 |

response to stress; target Mdm2 |

18 |

| miR-1204 |

cell death |

19 |

| miR-1246 | Target Down syndrome associated DYRK1A | 20 |

The p53 Family and miRNAs

Roles of miRNAs in p53 pathways.

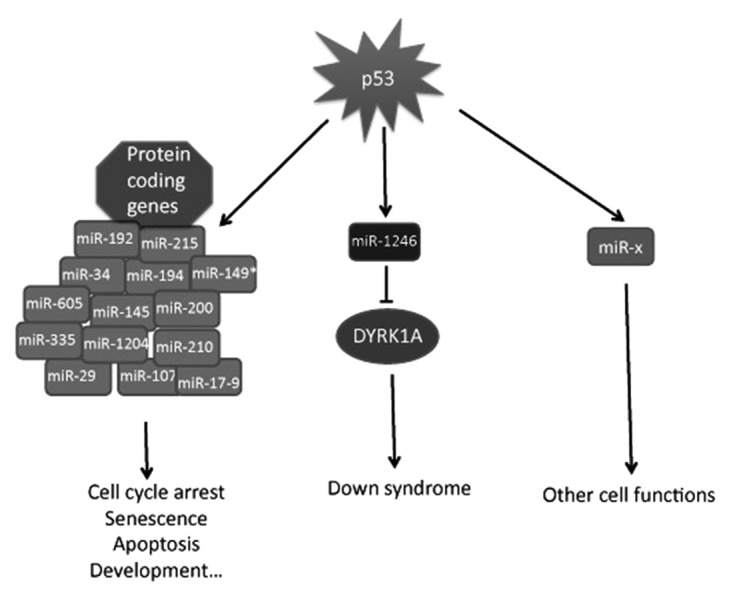

Since discovery of miR-34 as the first miRNA target of p53,7-9 a number of miRNAs have also been shown to play a role in p53-dependent cell growth control, apoptosis and senescence. These miRNAs include miR-34,7-9 miR-192,10 miR-194,10 miR-215,10 miR-145,11 miR-17–92 cluster,12 miR-107,13 miR-149*,14 miR-200,15 miR-210,16 miR-335,17 miR-605,18 miR-120419 and miR-1246 20 (Table 1). Each of their DNA promoter regions contains one or two p53-responsive element (p53RE), and their expressions are p53-dependent in response to various stress signals. In addition, both p53 and p63 were recently reported to affect post-transcriptional maturation of miRNA via regulation of the RISC complex.22,23 These two p53 family members appear to utilize different mechanisms in governing miRNA maturation. p53 was shown to bind to the Drosha complex and to promote the maturation of primary miRNAs to precursor miRNAs, while an inactive p53 mutant that lacks Drosha binding activity has no effect on this process.23 In contrast, p63 affects miRNA maturation by transcriptionally regulating the expression of Dicer, a protein that is essential for miRNA processing.22 These studies suggest that p53 and p63 may play a global role in modulation of miRNA expression. Because of the centrally important role of p53 and its family members in tumor suppression, most of the published studies on p53 family-targeting miRNAs have been focusing on the antitumor properties of these miRNAs, involving known p53-regulated pathways as illustrated in Figure 1. Recently miR-1246 was discovered as another target of this family,20 as detailed below.

Figure 1. Summary of the p53 target miRNAs. Most p53 targeting miRNAs are involved in known p53 functions including cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis.

Regulation of Down syndrome-associated DYRK1A by miR-1246.

In our initial attempt to identify possibly specific miRNA targets for p63 through miRNA microarray analysis, we unraveled miR‑1246 as a transcriptional target for all of the p53 family members, including p53, p63 and p73.20 This finding was further confirmed by several pieces of evidence. First, overexpression of either of these p53 family members induced the expression of endogenous mature miR-1246 and the luciferase expression driven by the miR-1246 promoter that contains wild type, but not mutant, p53RE sequence.20 Also, chromatin-mediated immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis showed that each of the p53 family members binds to the endogenous p53RE-containing promoter of this miRNA gene. Additionally, knockdown of each of these p53 family members led to the drastic reduction of miR-1246 expression.20 Therefore, these results demonstrate that miR-1246 is a bona fide transcriptional target of this p53 family.

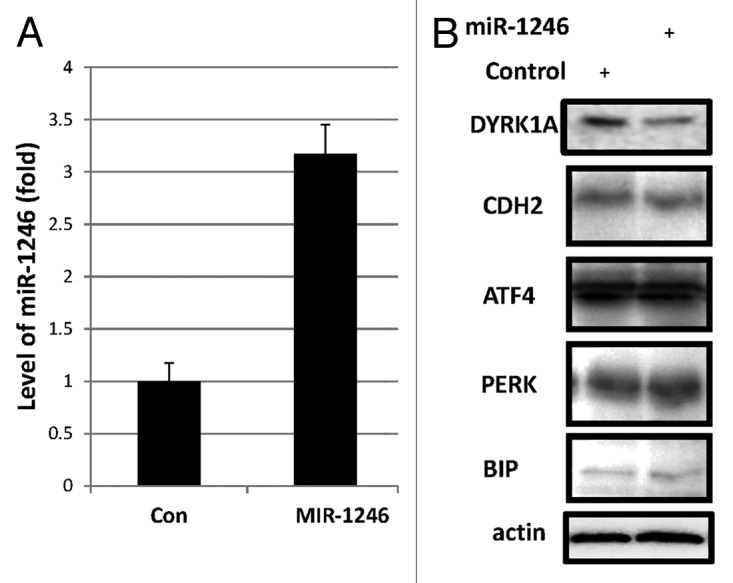

In order to search the mRNA targets of miR-1246, we conducted bioinformatic screening by using TargetScan24 and then examined the expression of several putative targets by employing western blot. As a result, we found that 3-fold induction of miR-1246 was sufficient to reduce the protein level of DYRK1A, but not the other putative targets, CDH2, ATF4, PERK and BIP, as shown in Figure 2. Since DYRK1A was previously shown to phosphorylate and inactivate NFAT and caspase 9,25,26 miR-1246, as expected, can activate NFAT and induce apoptosis by reducing the expression of DYRK1A.20 Interestingly, DYRK1A is one of the key proteins that are overexpressed in Down syndrome patients and has been shown to be associated with nerve development and brain physiology.21,27 Our studies not only suggest a novel pathway for the p53 family, i.e., the p53/p63/p73-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT pathway, but also imply that the family members might play a regulatory role in Down syndrome and/or central nerve development via miR-1246, as further discussed below.

Figure 2. Screening of miR-1246 targets by western blot (WB). H1299 cells were harvested 72 h after transiently transfected with miR-1246 for Q-RT-PCR analysis of mature miR-1246 levels (A) and for WB with antibodies as indicated (B). Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3)

The p53-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT Pathway and Cancer

DYRK1A may act as an oncoprotein.

The finding that p53 represses the expression of DYRK1A via miR-1246 20 suggests that DYRK1A might play an oncogenic role in neoplasia and tumorigenesis. Indeed, this guess is supported by several studies in the literature. The first evidence for the possible involvement of DYRK1A in tumorigenesis was the observation that DYRK1A is highly expressed in HPV16 immortalized keratinocytes and malignant cervical lesions compared with their primary foreskin keratinocytes and normal cervical tissues, respectively.28 In line with this result is the finding that knockdown of endogenous DYRK1A in HPV16 immortalized keratinocytes leads to apoptosis,28 suggesting that DYRK1A may act as a cell survival and anti-apoptotic molecule in cells. Consistent with this notion, DYRK1A appears to utilize several different mechanisms to inhibit apoptosis and to promote cell proliferation. First, DYRK1A phosphorylates caspase-9 and inhibits its ability to trigger apoptosis.26,29,30 Also, DYRK1A binds to and phosphorylates HPV16E7 at threonine 5 and threonine 7, and this phosphorylation makes this oncoprotein much more stable,31 consequently promoting cell proliferation and growth. Furthermore, DYRK1A has been shown to suppress apoptosis by phosphorylating and activating Sirt1, which, in turn, deacetylates p53 and inactivates its apoptotic activity.32 Recently, DYRK1A was reported to positively regulate the Wnt signaling in Xenopus laevis embryos and mammalian cells,33 stimulating cell growth. Finally, DYRK1A can activate an anti-apoptosis protein, WDR68, via regulation of its nuclear translocation.34 All of these lines of evidence support the concept that DYRK1A plays an oncogenic role by favoring cell proliferation and disfavoring apoptosis. Thus, it is logical and biologically significant that the p53 family members inactivate this kinase through miRNA-mediated (miR-1246) suppression of its expression.20 The discovery of this p53-miR-1246-DYRK1A pathway provides not only a new mechanism underlying the anti-oncogenic function of this remarkable tumor suppressor family, but also a reasonable explanation for those Down syndrome-associated cancers as discussed in the later section of this essay.

NFAT may act as another effector of p53.

The fact that NFAT is one of the downstream kinase targets of DYRK1A, which inactivates the former by phosphorylating it and consequently preventing its nuclear localization,25 and that p53 can reverse this and subsequently activate NFAT by suppressing the expression of this kinase20 suggest that NFAT might be another new, but indirect, effector of p53’s anticancer functions. Remarkably, this likely connection between p53 and NFAT in cancer prevention has also been demonstrated in a recent study using mouse and xenograft tumor models.35 This study showed that the ability of p53 to prevent skin squamous cancer development was severely impaired when the calcineurin/NFAT pathway was inhibited genetically and pharmacologically.35 Hence, these two cell-based and animal studies36,37 bridge the p53 pathway with the calcineurin-DYRK1A-NFAT pathway in a more biologically relevant context, i.e., in addition to activating a number of other pathways,38 p53 could also activate the NFAT pathway by negating the expression of DYRK1A via miR-1246 in order to maximally execute its anticancer functions. This new link could also imply that under an oncogenic urgency, p53, once activated, might boost up immune response against cancerous cells by activating NFAT via miR-1246-mediated suppression of DYRK1A, as NFAT has been shown to play a critical role in establishment of immune response as a transcriptional activator of numerous cytokines and their receptors, such as IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-8, IL-13, GM-CSF, IFNγ, TNFα, CD40L.39-45 Indeed, NFAT is a major target of the immunosuppressive drugs cyclosporin A and FK506.36,37 Therefore, NFAT may act as another player in the downstream of the p53 pathway against cancer, perhaps by enhancing immune response to cancer cells. In addition to being involved in the anticancer function of p53 family, the miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT pathway could also mediate the role of p73 in nerve and immune system development as discussed below.

Functional link of DYRK1A and NFAT with p73.

It is known that p73 is crucial for the development of central nerve and immune systems;1 however, the underlying mechanisms have remained incompletely understood. Since DYRK1A is associated with neuron development21,27 and NFAT is an important nuclear transcriptional factor for immune regulation,46 it is likely that the regulation of DYRK1A and NFAT activity by p73 via miR-124620 might partially account for the role of this p53 family member in central nerve and immune development.1 In this regard, p73, once activated, may induce the expression of miR-1246,20,47 which, in turn, represses the expression of DYRK1A and consequently activates the NFAT transcriptional activity by enhancing its nuclear localization in either neurons or immune cells. This mechanism, though it needs to validated, could logically explain the role of p73 in the development of both of the systems. Recently, another p53 targeting miRNA, miR-34a, was shown to be involved in the nerve development controlled by p73,1,48 as neurological and inflammatory defects were observed in p73-deficient mice,1 and miR-34a, but not 34b and c, was induced by p73 to target synaptotagmin-1 and syntaxin-1A in synaptic neurons during neuronal development.48 The p73-miR-34a axis plays a role in neuronal differentiation and synaptogenesis.48 Hence, miR-1246, perhaps like miR34a, as induced by p73, may also implement the important function of this transcriptional activator in central nerve and immune development by acting on the DRYK1A-NFAT pathway. Moreover, this p73-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT axis might also play a part in preventing tumor formation, including in the brain by boosting immune response as well as in Down syndrome development, as discussed about p53 below.

Role of the p53-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT Pathway in Down Syndrome

Higher or lower cancer incidences in down syndrome patients?

Since DYRK1A is highly expressed in Down syndrome patients due to trisomy 21 and is shown to promote cell survival and to inhibit apoptosis,26,28,31-34 it would be predicted that these patients might have the high risk of developing cancer. However, the story might not be this simple, as some Down syndrome-associated proteins were also found to induce apoptosis in cells, such as ETS2.49,50 Moreover, a population-based study pointed out that compared with healthy people, Down syndrome patients appear to have a lower chance to gain several common malignancies except leukemia and testicular cancer.51 This concept has been widely accepted, largely because the statistical analysis of data came from all the Down syndrome patients who died during 1983 to 1997 in the US. Hence, it has been puzzling why Down syndrome patients have high risks for leukemia and testicular cancers but low risks for other types of cancers if they possess high levels of the oncogenic DYRK1A. With this question in mind, we carefully reexamined the literature information, and our analysis revealed a surprising finding, which would overturn the previous concept. To our notice, the median age of cancer patients at diagnosis, who suffered of acute lymphocytic leukemia and testicular cancer,52 are approximately 13 and 33, which are actually the youngest and the second youngest among all the cancers, respectively. However, the overall median age of patients who are diagnosed with all types of cancers is 66.52 Apparently, acute leukemia and testicular cancer often occur to younger people. Because the average lifespan of Down syndrome patients is 49 y in 2002 and 25 y in 1980,51,53 we believe that Down syndrome patients are too young to develop other types of cancers except leukemia and testicular cancer (Tables 2 and 3). Based on this intriguing finding, it might be premature to conclude that the overall effect of trisomy 21 is to slow down cancer development in Down syndrome patients. Hence, re-investigating this mystery will be necessary to clarify this promiscuous assumption.

Table 2. Lifespan of Down syndrome patients and the median age of cancer patients at diagnosis.58,59.

| Groups | Lifespan of Down syndrome patients (years) | |

|---|---|---|

| |

In 1983 |

In 1997 |

| women |

26 |

50 |

| men |

24 |

49 |

| White people |

29 |

50 |

| Black people | 3 | 23 |

Table 3. Median age of cancer patients at diagnosis.

| Tumor site | Median age of cancer patients at diagnosis |

|---|---|

| All Sites |

67.0 |

|

Acute lymphocytic Leukemia |

13.0 |

|

Testis |

34.0 |

| Oral Cavity and Pharynx |

62.0 |

| Digestive System |

71.0 |

| Respiratory System |

70.0 |

| Breast | 61.0 |

Role of p53 in cancer incidents of Down syndrome patients.

Prior to our discovery of p53 as an upstream regulator of DYRNK1A and NFAT via miR‑1246,20 p53 has been reported to play a double-edged sword-type role in Down syndrome. On one hand, p53 induces apoptosis and consequent neurodegeneration, which is associated with neuro-pathological alterations in Down syndrome. On the other hand, p53 prevents tumorigenesis by inducing the same lethal cellular phenotype in Down syndrome. Consistent with these notions is that p53 is detected at a high level in postmortem central nervous system tissues from Down syndrome patients.54-57 Also, p53 was shown to mediate neuron apoptosis and death as induced by some Down syndrome-associated genes, such as Ets2 and PREP1. Overexpression of Ets2 was found in Down syndrome patients and promoted Down syndrome-associated neuronal apoptosis.49 The p53-dependent apoptosis was also observed in a Down syndrome mouse model with an extra copy of ets2.49,50 Remarkably, this Down syndrome phenotype of ets2 transgenic mice was rescued by further deleting TP53, indicating that p53 is primarily responsible for the neuro-pathological phenotype in Down syndrome caused by overexpression of ets2.50 In addition, overexpression of Prep1, another trisomy 21 gene, also induced p53 level and p53-dependent apoptosis, as demonstrated in fibroblasts obtained from Down syndrome patients.58 Clearly, similar to the pathological role of p53 in bone marrow developmental defects,59 p53, when abnormally active, also serves as a pathogenic agent in Down syndrome development.

However, the positive aspect of overly active p53 in Down syndrome patients is that it also counteracts cancer development in the patients. Indeed, a benign form of leukemia, transient leukemia, is often found in newborn infants with Down syndrome.60 It was suggested that p53 might play vital roles during the transition from transient leukemia to acute megakaryoblastic leukemia, for p53 mutations or deletion were found in two of three Down syndrome patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia61 as well as in a Down syndrome-bearing infant with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia.62 These studies validate the anticancer function of p53 in Down syndrome patients. However, there are some trisomy 21 gene-encoded proteins that antagonize the p53 function. For example, S100B, whose level increases in early stages of Down syndrome, could bind to p53 and inhibit p53 oligomerization.63 Also, the lifespan of p53+/- mice increased after crossing with Down syndrome Ts65Dn mouse model,64 suggesting the inhibitory action of Ts65Dn on p53 activity. Altogether, these studies suggest that p53 plays both pathological and anticancer roles in Down syndrome.

Down syndrome and the p53-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT axis.

Then how does p53 exactly work in playing such a double-edged sword-type role in Down syndrome development? Addressing this question is not an easy task because of the complexity of Down syndrome. This is a genetic disease with mental retardation and Alzheimer-like dementia due to trisomy of chromosome 21.65,66 Because of this unusual chromosomal abnormality, over 200 genes in chromosome 21 have three copies and are thus highly expressed in Down syndrome patients.66 Among them, Dyrk1a is one of the most important genes highly responsible for motor deficits and early deposition of β-amyloid in Down syndrome patients,27,67,68 in addition to the aforementioned ets2.49,50 The causal role of Dyrk1a in motor dysfunction and mental retardation, which are major clinical manifestations and symptoms in Down syndrome, has also been manipulated in a transgenic mouse model with an extra copy of Dyrk1a.68 Biochemically, DYRK1A is a serine/threonine protein kinase with diverse protein targets and can be self-activated by autophosphorylation during translation,69,70 although this phosphorylation might not be necessary for maintaining its activity once activated, as in vitro dephosphorylated DYRK1A still possesses kinase activity.71 Most likely, DYRK1A is regulated at the protein level, and the balance of DYRK1A level is thus vitally important for neurodevelopment.72,73 Because miR-1246 in response to active p53 can bind to DYRK1A mRNA and inhibit its translation, consequently reducing the protein level of DYRK1A as described above,20 we speculate that the downregulation of DYRK1A level by p53 or p73 via miR-1246 might play a role in restricting Down syndrome development while also preventing cancer formation. Consistent with this conjecture is a good correlation between the lifespan of Down syndrome patients and the status of p53 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). It has been shown that the p53 protein with proline 72 (P72) is less active as a transcriptional activator than that with arginine 72 (R72).74 Interestingly, approximately 80% white people, but only ~10% black people, harbor the p53 R72 version.74 This difference in p53 SNP between white and black people coincides well with the difference in the lifespan of those who suffer of Down syndrome. White people with Down syndrome could live for about 50 y, whereas black people who suffer of the same disease can live for only 25 years.51 This human genetic evidence suggests that p53 might play an overall protective role in Down syndrome patients, though it is also responsible for the pathological phenotypes of the patients. One of the mechanisms underlying this protective function of p53 could be through the miR-1246-mediated suppression of DYRK1A. Further investigating the role of the p53-miR-1246-DYRK1A-NFAT axis in Down syndrome using animal models will certainly consolidate this notion.

Remaining Questions

Although identification of miR-1246 as another p53 target that can suppress the expression of Down syndrome-associated DYRK1A offers a potential mechanism for the role of p53 in the development of this disease, a number of outstanding questions remain to be addressed in addition to those as aforementioned. First, is DYRK1A the only target of miR-1246 associated with this genetic disease? Also, would the deficiency of p53 be able to rescue the phenotypes of Down syndrome as caused by overexpression of DYRK1A in mice? Furthermore, since DSCR1, another trisomy 21 gene, was shown to inhibit NFAT activity by cooperating with DYRK1A,25,75 could p53 or p73 negate the expression of DSCR1 via a similar mechanism to that of DYRK1A, either through miR-1246 or other p53 target miRNAs, such as miR‑34a? Moreover, could miR‑1246 serve as a therapeutic agent for Down syndrome? Finally, does miR-1246 or NFAT1c play a role in preventing human cancer development and progression? Addressing these questions, though an incomplete list, will offer a better picture about the role of p53 in Down syndrome development and the role of miR-1246 in this disease and cancer development in patients with this genetic disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenjuan Liao for modifying Figure 1. This work was supported in part by NIH-NCI grants CA127724, CA095441 and CA129828 to H.L.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/20809

References

- 1.Yang A, Walker N, Bronson R, Kaghad M, Oosterwegel M, Bonnin J, et al. p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours. Nature. 2000;404:99–103. doi: 10.1038/35003607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999;398:714–8. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:708–13. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr., Butel JS, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–21. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belyi VA, Ak P, Markert E, Wang H, Hu W, Puzio-Kuter A, et al. The origins and evolution of the p53 family of genes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001198. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boominathan L. The guardians of the genome (p53, TA-p73, and TA-p63) are regulators of tumor suppressor miRNAs network. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:613–39. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447:1130–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corney DC, Flesken-Nikitin A, Godwin AK, Wang W, Nikitin AY. MicroRNA-34b and MicroRNA-34c are targets of p53 and cooperate in control of cell proliferation and adhesion-independent growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8433–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun CJ, Zhang X, Savelyeva I, Wolff S, Moll UM, Schepeler T, et al. p53-Responsive micrornas 192 and 215 are capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10094–104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachdeva M, Zhu S, Wu F, Wu H, Walia V, Kumar S, et al. p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2009;106:3207–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808042106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan HL, Xue G, Mei Q, Wang YZ, Ding FX, Liu MF, et al. Repression of the miR-17-92 cluster by p53 has an important function in hypoxia-induced apoptosis. EMBO J. 2009;28:2719–32. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böhlig L, Friedrich M, Engeland K. p53 activates the PANK1/miRNA-107 gene leading to downregulation of CDK6 and p130 cell cycle proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:440–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin L, Hu WL, Jiang CC, Wang JX, Han CC, Chu P, et al. MicroRNA-149*, a p53-responsive microRNA, functions as an oncogenic regulator in human melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2011;108:15840–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knouf EC, Garg K, Arroyo JD, Correa Y, Sarkar D, Parkin RK, et al. An integrative genomic approach identifies p73 and p63 as activators of miR-200 microRNA family transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:499–510. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutharasan RK, Nagpal V, Ichikawa Y, Ardehali H. microRNA-210 is upregulated in hypoxic cardiomyocytes through Akt- and p53-dependent pathways and exerts cytoprotective effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1519–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01080.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scarola M, Schoeftner S, Schneider C, Benetti R. miR-335 directly targets Rb1 (pRb/p105) in a proximal connection to p53-dependent stress response. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6925–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao J, Lin H, Luo X, Luo X, Wang Z. miR-605 joins p53 network to form a p53:miR-605:Mdm2 positive feedback loop in response to stress. EMBO J. 2011;30:524–32. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barsotti A, Beckerman R, Laptenko O, Huppi K, Caplen NJ, Prives C. P53-dependent induction of PVT1 and MIR-1204. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2509–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Liao JM, Zeng SX, Lu H. p53 downregulates Down syndrome-associated DYRK1A through miR-1246. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:811–7. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker W, Sippl W. Activation, regulation, and inhibition of DYRK1A. FEBS J. 2011;278:246–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su X, Chakravarti D, Cho MS, Liu L, Gi YJ, Lin YL, et al. TAp63 suppresses metastasis through coordinate regulation of Dicer and miRNAs. Nature. 2010;467:986–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki HI, Yamagata K, Sugimoto K, Iwamoto T, Kato S, Miyazono K. Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature. 2009;460:529–33. doi: 10.1038/nature08199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao JM, Lu H. Autoregulatory suppression of c-Myc by miR-185-3p. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33901–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.262030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwack Y, Sharma S, Nardone J, Tanasa B, Iuga A, Srikanth S, et al. A genome-wide Drosophila RNAi screen identifies DYRK-family kinases as regulators of NFAT. Nature. 2006;441:646–50. doi: 10.1038/nature04631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laguna A, Aranda S, Barallobre MJ, Barhoum R, Fernández E, Fotaki V, et al. The protein kinase DYRK1A regulates caspase-9-mediated apoptosis during retina development. Dev Cell. 2008;15:841–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toiber D, Azkona G, Ben-Ari S, Torán N, Soreq H, Dierssen M. Engineering DYRK1A overdosage yields Down syndrome-characteristic cortical splicing aberrations. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:348–59. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang HS, Lin CH, Yang CH, Yen MS, Lai CR, Chen YR, et al. Increased expression of Dyrk1a in HPV16 immortalized keratinocytes enable evasion of apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2377–85. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seifert A, Allan LA, Clarke PR. DYRK1A phosphorylates caspase 9 at an inhibitory site and is potently inhibited in human cells by harmine. FEBS J. 2008;275:6268–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seifert A, Clarke PR. p38alpha- and DYRK1A-dependent phosphorylation of caspase-9 at an inhibitory site in response to hyperosmotic stress. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1626–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang YJ, Chang HS, Wang CY, Yu WC. DYRK1A stabilizes HPV16E7 oncoprotein through phosphorylation of the threonine 5 and threonine 7 residues. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2431–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo X, Williams JG, Schug TT, Li X. DYRK1A and DYRK3 promote cell survival through phosphorylation and activation of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13223–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong JY, Park JI, Lee M, Muñoz WA, Miller RK, Ji H, et al. Down’s-syndrome-related kinase Dyrk1A modulates the p120-catenin-Kaiso trajectory of the Wnt signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:561–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyata Y, Nishida E. DYRK1A binds to an evolutionarily conserved WD40-repeat protein WDR68 and induces its nuclear translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1728–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu X, Nguyen BC, Dziunycz P, Chang S, Brooks Y, Lefort K, et al. Opposing roles for calcineurin and ATF3 in squamous skin cancer. Nature. 2010;465:368–72. doi: 10.1038/nature08996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunol Today. 1992;13:136–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90111-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigal NH, Dumont FJ. Cyclosporin A, FK-506, and rapamycin: pharmacologic probes of lymphocyte signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:519–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137:609–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rooney JW, Sun YL, Glimcher LH, Hoey T. Novel NFAT sites that mediate activation of the interleukin-2 promoter in response to T-cell receptor stimulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6299–310. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamoto S, Mukaida N, Yasumoto K, Rice N, Ishikawa Y, Horiguchi H, et al. The interleukin-8 AP-1 and kappa B-like sites are genetic end targets of FK506-sensitive pathway accompanied by calcium mobilization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8582–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stranick KS, Payvandi F, Zambas DN, Umland SP, Egan RW, Billah MM. Transcription of the murine interleukin 5 gene is regulated by multiple promoter elements. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20575–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dolganov G, Bort S, Lovett M, Burr J, Schubert L, Short D, et al. Coexpression of the interleukin-13 and interleukin-4 genes correlates with their physical linkage in the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosome 5q23-31. Blood. 1996;87:3316–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho IC, Hodge MR, Rooney JW, Glimcher LH. The proto-oncogene c-maf is responsible for tissue-specific expression of interleukin-4. Cell. 1996;85:973–83. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karlen S, D’Ercole M, Sanderson CJ. Two pathways can activate the interleukin-5 gene and induce binding to the conserved lymphokine element 0. Blood. 1996;88:211–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Splawski JB, Nishioka J, Nishioka Y, Lipsky PE. CD40 ligand is expressed and functional on activated neonatal T cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boominathan L. The tumor suppressors p53, p63, and p73 are regulators of microRNA processing complex. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agostini M, Tucci P, Steinert JR, Shalom-Feuerstein R, Rouleau M, Aberdam D, et al. microRNA-34a regulates neurite outgrowth, spinal morphology, and function. 2011;Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112063108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helguera P, Pelsman A, Pigino G, Wolvetang E, Head E, Busciglio J. ets-2 promotes the activation of a mitochondrial death pathway in Down’s syndrome neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2295–303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5107-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolvetang EJ, Wilson TJ, Sanij E, Busciglio J, Hatzistavrou T, Seth A, et al. ETS2 overexpression in transgenic models and in Down syndrome predisposes to apoptosis via the p53 pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:247–55. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. Mortality associated with Down’s syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. Lancet. 2002;359:1019–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, et al. Edwards BK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2011.

- 53.Young E. Down's syndrome lifespan doubles. New Sci. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 54.de la Monte SM, Sohn YK, Ganju N, Wands JR. P53- and CD95-associated apoptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Lab Invest. 1998;78:401–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawa A. Neuronal cell death in Down’s syndrome. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1999;57:87–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6380-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seidl R, Fang-Kircher S, Bidmon B, Cairns N, Lubec G. Apoptosis-associated proteins p53 and APO-1/Fas (CD95) in brains of adult patients with Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 1999;260:9–12. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00945-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawa A. Alteration of gene expression in Down’s syndrome (DS) brains: its significance in neurodegeneration. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2001;61:361–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6262-0_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Micali N, Longobardi E, Iotti G, Ferrai C, Castagnaro L, Ricciardi M, et al. Down syndrome fibroblasts and mouse Prep1-overexpressing cells display increased sensitivity to genotoxic stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3595–604. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elghetany MT, Vyas S, Yuoh G. Significance of p53 overexpression in bone marrow biopsies from patients with bone marrow failure: aplastic anemia, hypocellular refractory anemia, and hypercellular refractory anemia. Ann Hematol. 1998;77:261–4. doi: 10.1007/s002770050455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zipursky A. Transient leukaemia--a benign form of leukaemia in newborn infants with trisomy 21. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:930–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malkin D, Brown EJ, Zipursky A. The role of p53 in megakaryocyte differentiation and the megakaryocytic leukemias of Down syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;116:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(99)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marques-Salles TdeJ, Mkrtchyan H, Leite EP, Soares-Ventura EM, Muniz MT, Silva EF, et al. Complex karyotype defined by molecular cytogenetic FISH and M-FISH in an infant with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia and neurofibromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;200:167–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fernandez-Fernandez MR, Veprintsev DB, Fersht AR. Proteins of the S100 family regulate the oligomerization of p53 tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2005;102:4735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501459102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang A, Reeves RH. Increased survival following tumorigenesis in Ts65Dn mice that model Down syndrome. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3573–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ball MJ, Nuttall K. Neurofibrillary tangles, granulovacuolar degeneration, and neuron loss in Down Syndrome: quantitative comparison with Alzheimer dementia. Ann Neurol. 1980;7:462–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.410070512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roizen NJ, Patterson D. Down’s syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1281–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12987-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kimura R, Kamino K, Yamamoto M, Nuripa A, Kida T, Kazui H, et al. The DYRK1A gene, encoded in chromosome 21 Down syndrome critical region, bridges between beta-amyloid production and tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:15–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martínez de Lagrán M, Altafaj X, Gallego X, Martí E, Estivill X, Sahún I, et al. Motor phenotypic alterations in TgDyrk1a transgenic mice implicate DYRK1A in Down syndrome motor dysfunction. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kentrup H, Becker W, Heukelbach J, Wilmes A, Schürmann A, Huppertz C, et al. Dyrk, a dual specificity protein kinase with unique structural features whose activity is dependent on tyrosine residues between subdomains VII and VIII. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3488–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Himpel S, Panzer P, Eirmbter K, Czajkowska H, Sayed M, Packman LC, et al. Identification of the autophosphorylation sites and characterization of their effects in the protein kinase DYRK1A. Biochem J. 2001;359:497–505. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adayev T, Chen-Hwang MC, Murakami N, Lee E, Bolton DC, Hwang YW. Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A does not require tyrosine phosphorylation for activity in vitro. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7614–24. doi: 10.1021/bi700251n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hämmerle B, Elizalde C, Galceran J, Becker W, Tejedor FJ. The MNB/DYRK1A protein kinase: neurobiological functions and Down syndrome implications. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2003;67:129–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6721-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park J, Song WJ, Chung KC. Function and regulation of Dyrk1A: towards understanding Down syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3235–40. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0123-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeong BS, Hu W, Belyi V, Rabadan R, Levine AJ. Differential levels of transcription of p53-regulated genes by the arginine/proline polymorphism: p53 with arginine at codon 72 favors apoptosis. FASEB J. 2010;24:1347–53. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-146001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arron JR, Winslow MM, Polleri A, Chang CP, Wu H, Gao X, et al. NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature. 2006;441:595–600. doi: 10.1038/nature04678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]