Abstract

Posttranslational modifications of p53 integrate diverse stress signals and regulate its activity, but their combinatorial contribution to overall p53 function is not clear. We investigated the roles of lysine (K) acetylation and sumoylation on p53 and their relation to apoptosis and autophagy. Here we describe the collaborative role of the SUMO E3 ligase PIASy and the lysine acetyltransferase Tip60 in p53-mediated autophagy. PIASy binding to p53 and PIASy-activated Tip60 lead to K386 sumoylation and K120 acetylation of p53, respectively. Even though these two modifications are not dependent on each other, together they act as a “binary death signal” to promote cytoplasmic accumulation of p53 and execution of PUMA-independent autophagy. PIASy-induced Tip60 sumoylation augments p53 K120 acetylation and apoptosis. In addition to p14ARF inactivation, impairment in this intricate signaling may explain why p53 mutations are not found in nearly 50% of malignancies.

Keywords: PIASy, Tip60, acetylation, apoptosis, autophagy, p53, sumoylation and tumor suppressors

Introduction

Tumor suppressors play an integral role in preventing accumulation of harmful and potentially oncogenic mutations. The tumor suppressor p53 promotes transcription of growth arrest or apoptotic genes to eliminate the premalignant cells.1-5 Activation of p53 involves multiple covalent modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination.2 The lysine acetyl transferases (KATs) p300/CBP and pCAF acetylate p53 and are proposed to facilitate transcription and out compete ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation.6,7 The DNA damage signal transduction factor ATM complexes with the KAT protein Tip60 and induces its acetyltransferase activity.8 Tip60 acetylates p53 on lysine 120 (K120) within the DNA binding domain, which results in transcription of the pro-apoptotic gene PUMA.9,10 In a large-scale RNAi screen, Tip60 was also found to be necessary for p14ARF-induced p53 activation.11 Furthermore, in vivo studies demonstrate that Tip60 functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor.12

In response to DNA damage and oncogenic cues, p53 activates transcription of genes critical for cell cycle, apoptosis and autophagy, which are mediated in part by p21cip1, PUMA and damage-regulated autophagy modulator (DRAM), respectively.13,14 Apoptosis is a death program that depends upon mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and eventuates in activation of caspases. PUMA binds to Bcl-2 protein to stimulate the mitochondrial cell death pathway.15-17 Mechanistically, PUMA dislodges cytoplasmic p53 bound to BCL-xL and causes Bax-mediated apoptosis.18 Autophagy is another p53-regulated cytoplasmic defense mechanism that responds to diverse stress conditions.19 p53 integrates signals that originate from various stress responses in a complex growth-promoting environment and promotes autophagy.20,21 How posttranslational modifications of p53 discriminate its selectivity for each of these transcriptional targets and the respective biological programs to induce apoptosis or autophagy is not known. Acetylation of p53 lysine is dispensable for the p53-induced transcription of mdm2, which regulates p53 levels, but lysine acetylations are critical for transcriptional activation of other p53 targets.22 How these p53 lysine acetylations and other modifications integrate various stress signals to contribute to overall p53-induced cell death also remains unclear.

Sumoylation regulates cellular processes such as nucleo-cytoplasmic transport, transcription and DNA repair.23-26 Desumoylating enzymes allow dynamic regulation and have become an important target for therapeutics.27 The role of sumoylation in p53 transcription function and its biological consequences remains elusive. Early studies showed that Ubc9 promotes p53 sumoylation, and this enhances its transcriptional activity.28 However, purified sumoylated p53 failed to activate p53-dependent transcription in vitro.29 PIAS1, a member of PIAS SUMO ligase family, was shown to complex with Ubc9 and SUMO peptides to stimulate p53 sumoylation.30 Overexpression of another PIAS family member, PIASy, in human primary fibroblasts provoked a p53-dependent cellular senescence and apoptotic response.31 These studies highlight an important but incompletely defined function for p53 sumoylation.

Although most studies have focused on the nuclear-localized pool of p53 and its transcriptional role in tumor-suppressor function,32 recognition of the “cytoplasmic form of p53” has spurred interest in transcription-independent functions of p53.33,34 Interestingly, a truncated form of p53 lacking a DNA-binding domain induces apoptosis despite impaired transcriptional activity.35 The fact that p53 retains its apoptotic response in the absence of the nucleus or transcription highlights an important cytoplasmic cell death activity of p53.36,37 Furthermore, Mdm2-mediated monoubiquitination of p53 causes cytoplasmic accumulation, which promotes mitochondrial permeabilization-induced cell death.5,38 Although the biological outcome was unclear, it was shown that mdm2 cooperates with PIASy and enhances cytoplasmic translocation of p53.39 Nonetheless, in vivo studies show that knockout of p53 targets do not phenocopy the tumor development in p53-null mice,40 and transcriptionally defective p53 retains tumor-suppressor function, suggesting a direct role for activated p53 protein in overall tumor-suppressor function.37,41

Several cellular proteins regulate Tip60 in modulating the DNA damage response.42-46 Although these factors negatively regulate Tip60, the role of important DNA damage response pathway, PIASy’s effects on Tip60, and their interplay with p53 remain obscure. Here we describe a signaling pathway that connects these upstream p53 regulators, and their coordinated actions on p53 lead to PUMA-independent autophagic cell death.

Results

p53-induced autophagy is PUMA-independent.

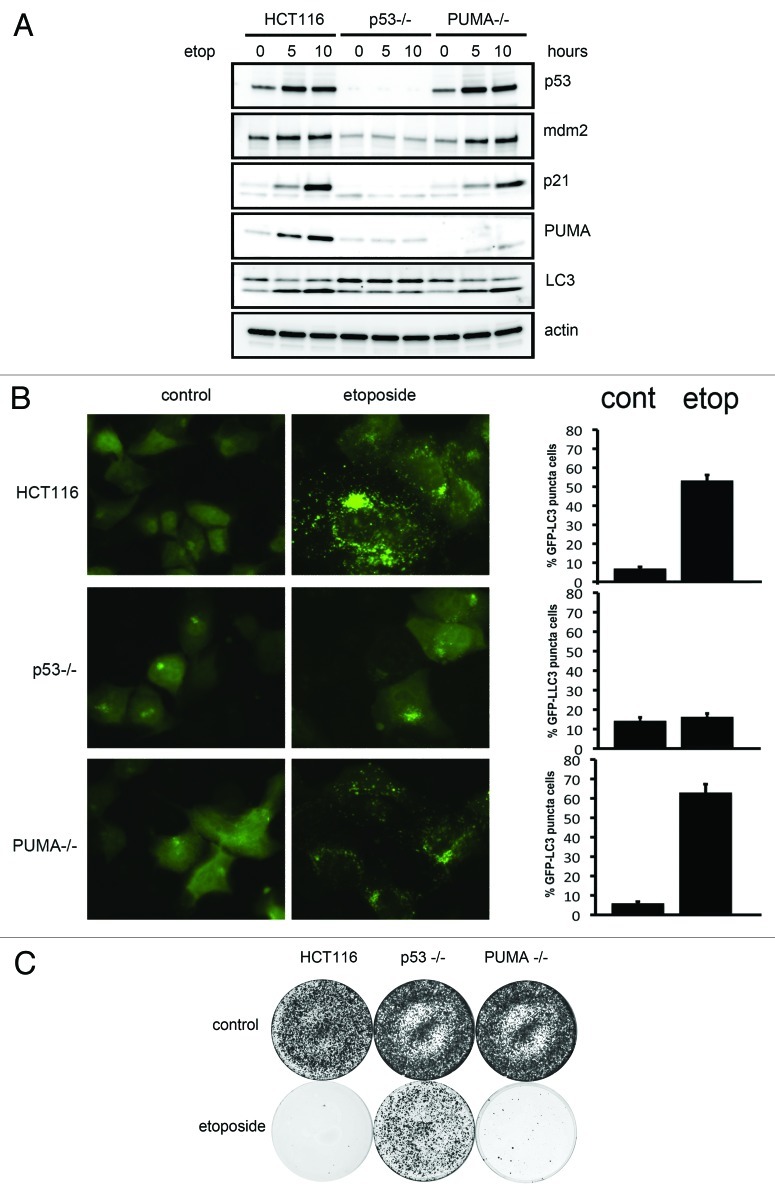

We initially questioned whether PUMA is required for p53-induced autophagy. PUMA-null and p53-null isogenic lines derived from HCT116 cells were treated with etoposide and examined for p53 activation and autophagy induction. As expected, the transcriptional targets of p53, including p21cip1, mdm2 and PUMA, were induced in parental HCT116 cells but not in p53-null cells (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, when these extracts were blotted with LC3 antibodies, a gradual increase in the LC3 II protein, the lipidated form indicative of autophagy, was observed in parental cells HCT116 and PUMA-null cells, but not in p53-null cells (Fig. 1A). Cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were treated with etoposide to evaluate autophagy. Consistent with the previous observation, etoposide-treated HCT116 cells and PUMA-null cells displayed GFP puncta that were not observed in untreated or p53-null cells (Fig. 1B). To corroborate these results, colony assays were performed to assess cell viability after DNA damage. Etoposide inhibited colony formation of the parental HCT116 cells and PUMA-null cells, while the p53-null cells were able to proliferate and form colonies (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. DNA damage induced autophagy is p53 dependent and PUMA independent. (A) Wild-type, p53-null or PUMA-null HCT116 cells were treated with etoposide for up to 10 h. Whole-cell lysates were blotted with the indicated antibodies (B) Control or etoposide treated wild-type, p53-null or PUMA-null HCT116 cells expressing GFP-LC3 were visualized for GFP puncta in three independent experiments. (C) HCT116 cells were transfected with a puromycin resistance gene and exposed to etoposide (bottom set). Proliferating puromycin resistant colonies were stained with crystal violet.

To evaluate the involvement of macroautophagy, ATG5 was depleted in PUMA-null HCT116 cells, and p53-dependent autophagy was assessed. We observed that p53-induced LC3 conversion and GFP-LC3 puncta were reduced by siRNA depletion of ATG5 (Fig. S1A and B).

p53 K120 and K386 arginine mutants are defective for induction of autophagy.

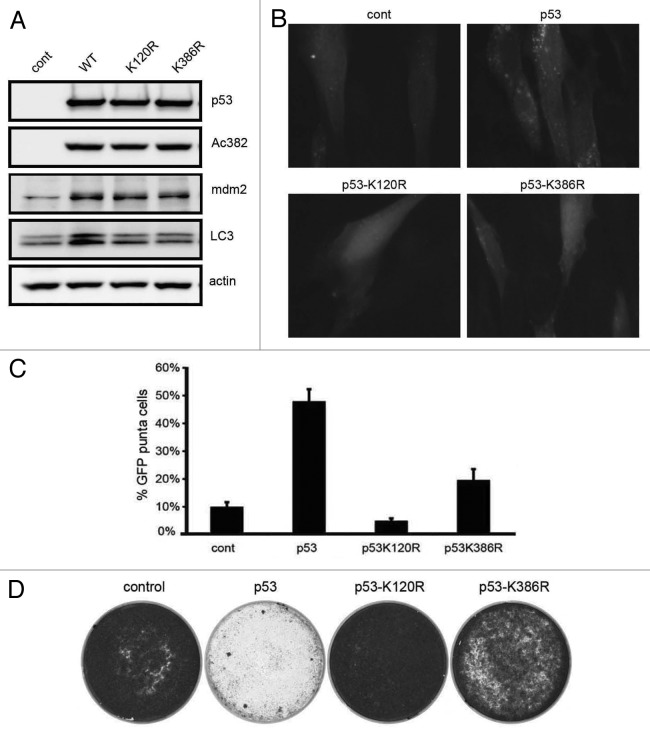

Having demonstrated that p53-dependent autophagy does not require PUMA expression and in consideration of prior data that sumoylation regulates response to DNA damage,31,47,48 we reasoned that p53 K120 and K386 positions might be critical for stimulation of autophagy. To address this, the biochemical and biological effects of p53 K120R and K386R were evaluated in transfected Saos2 cells. We chose to use Saos2 cells, because these cells are null for p53 gene, are easily transfected and have been used to study the biological effects of p53 mutants.49 Cell lysates were blotted with LC3 antibody to evaluate autophagy. Although K120R and K386R showed similar levels of mdm2 induction, only wt-p53 promoted LC3 II conversion (Fig. 2A). As a biological indicator of autophagy, Saos2 cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 and GFP puncta visualized. 50% of wt-p53 transfected cells showed GFP puncta; in contrast, < 10% of K120R and ~20% of K386R-transfected cells showed GFP puncta, implying that only wt-p53 extensively induced autophagy (Fig. 2B and C). We also evaluated cell survival by colony-formation assay following the introduction of wt p53, K120R or K386R plasmids along with a puromycin resistance encoding plasmid. Wild-type p53 efficiently inhibited cell growth, while p53 K120R- and K386R-expressing cells formed proliferative colonies (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. p53 K120R and K386R mutations fail to induce autophagy. (A) Saos2 cells were transfected with p53, K120R or K386R and whole cell extracts immunoblotted for indicated proteins. (B and C) Saos2 cells were transfected with indicated expression-plasmids along with GFP-LC3. LC3 puncta were counted in100 cells from three independent transfections. Error bars represent standard error. (D) Saos2 cells were co-transfected with control vector or wild-type, K120R or K386R p53 along with a puromycin-resistance encoding plasmid. Cells were selected with puromycin and the colonies stained with crystal violet.

p53-induced autophagy is linked to its cytoplasmic localization.

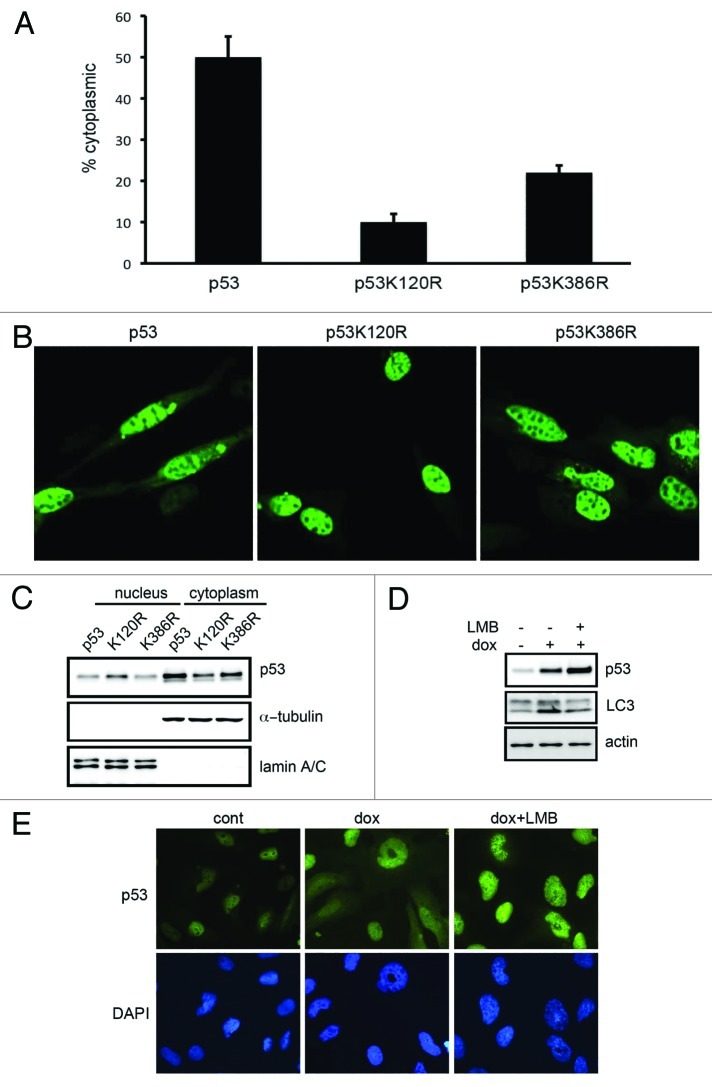

Because K120 and K386 amino acid positions of p53 play a crucial role in autophagy yet PUMA is not required, we reasoned that these modifications might be linked to cytoplasmic function of p53 and autophagy. In wt-p53 transfected Saos2 cells, we observed that nearly 50% of transfected cells showed detectable cytoplasmic p53 (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, p53 K120R protein was predominantly nuclear, while only ~20% of K386R showed cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 3A and B). To confirm these results biochemically, subcellular fractionation and immunoblotting were performed, with cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts probed by antibodies to α-tubulin and lamin A/C, respectively, to assess the composition of each fraction. Significantly more wt-p53 protein was present in the cytoplasmic extracts compared with the K120R and K386R mutant proteins (Fig. 3C). To further substantiate these data with endogenous p53 protein, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with doxorubicin to induce p53-dependent autophagy. Because SH-SY5Y cells have relatively large cytoplasmic area, we chose this cell type to study cytoplasmic localization of p53. We observed that doxorubicin-activated p53 accumulated in the cytoplasm, and treatment with leptomycin B (LMB), a nuclear export inhibitor, resulted in predominantly nuclear localization of p53. These results correlated with reduced LC3 II conversion upon treatment with LMB (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. p53 mutants K120R and K386R do not accumulate in the cytoplasm. (A and B) Saos2 cells were transfected, fixed with paraformaldehyde and p53 localization was observed. Cells showing cytoplasmic-p53 localization were counted and shown in the bar graph. Error bars represent standard error. (C) Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of Saos2 cells transfected and analyzed for p53 subcellular distribution. (D) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with doxorubicin in the presence or absence of leptomycin B (LMB) and the protein extracts were probed with indicated antibodies. (E) Cells treated as in (D) were examined for p53 localization.

PIASy binds and sumoylates Tip60 and p53.

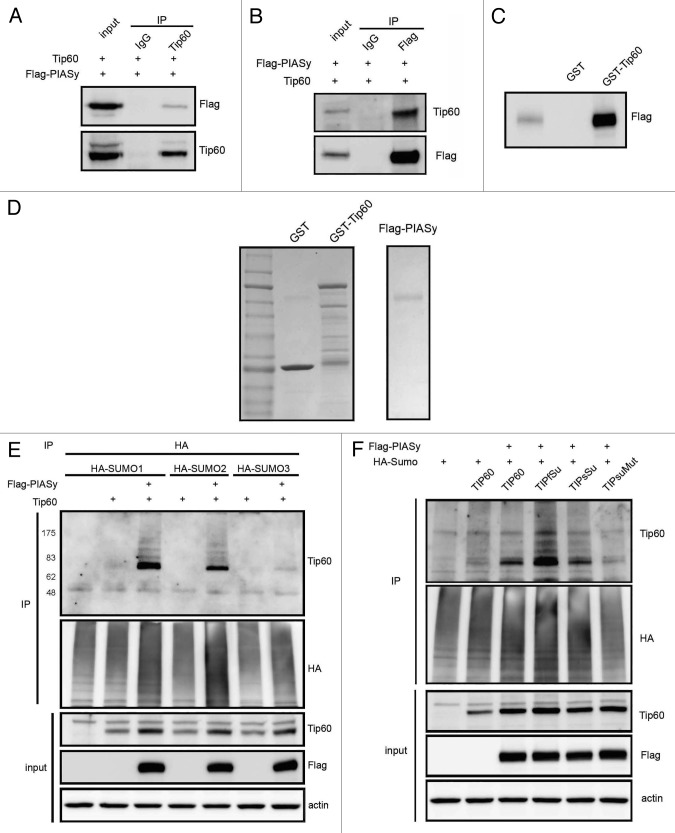

Sumoylation and acetylation exert documented roles in response to genotoxic insults.9,10,47,48 How these posttranslational modifications collaborate to influence p53-mediated death programs remains unclear. Tip60-induced p53 K120 acetylation is known to induce PUMA expression. To investigate the potential physical association of PIASy with Tip60, we expressed PIASy and Tip60 proteins in hTERT immortalized RPE1 cells. Immunoprecipitations with anti-Tip60 or anti-Flag (PIASy) antibodies followed by immunoblot with the reciprocal antibody revealed their co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4A and B). To address their direct interactions, GST-Tip60 purified from bacteria was incubated with Flag-PIASy that was expressed in H1299 cells and purified on Flag beads (Fig. 4D). GST pulldown showed that GST-Tip60 efficiently bound to Flag-PIASy in vitro (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. PIASy interacts with and sumoylates Tip60. (A and B) RPE1 cells transfected with Flag-PIASy and Tip60 were immunoprecipitated with Tip60 or Flag antibodies and immunoblots were probed with reciprocal antibodies. (C) In vitro pull-down assay using the semi-purified proteins showing PIASy binds to GST-Tip60. (D) Coomassie blue staining of semi-purified proteins. (E) RPE1 cells transfected with HA tagged SUMO orthologs in the presence or absence of PIASy along with Tip60. After immunoprecipitation with HA antibody, proteins were blotted with Tip60 or HA antibodies. (F) Cells were transfected as in (D) with Tip60 or first (TIPfSu), second (TIPsSu) or double (TIPsuMut) sumo consensus site K-R mutants along with HA-SUMO1 and the cell extracts immunoblotted as indicated.

While SUMO modification of Tip60 has been reported,50 the responsible E3 ligase and the biological consequences are not known. Although PIASy-mediated sumoylation was demonstrated by in vitro experiments,31 this has been problematic to demonstrate in vivo.39 Because Tip60 is critical for an apoptotic response, and cells overcome apoptosis to become malignant, we reasoned that regulation of Tip60 activity might be compromised in tumor-derived cells. Therefore, we chose to use non-transformed RPE1 cells to study PIASy-mediated sumoylation. HA-tagged SUMO-1, -2 and -3 proteins and Tip60 were expressed in RPE1 cells in the presence or absence of PIASy. Tip60 blotting of the HA antibody immumnoprecipitates revealed that PIASy stimulated robust SUMO1 conjugation to Tip60 (Fig. 4E). The E2 SUMO-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 has been reported to sumoylate Tip60 on lysines 430 and 451. To examine whether the E3 ligase PIASy sumoylates these residues, Tip60 mutants K430R, K451R and K430/451R were constructed. In vivo sumoylation assay confirmed that K430 and K451 of Tip60 were sumoylated, whereas mutation of these two positions abolished sumoylation (Fig. 4F). Although sumoylated Tip60 would appear as single band on the gel, we suspect that the faint bands that migrate slower than major sumoylated Tip60 protein are sumoylated and monoubiquitinated forms. To explore sumoylation of native Tip60, we exposed HA-SUMO transfected HCT116 cells to etoposide and found increased sumoylation of endogenous Tip60 upon probing with the HA antibody (Fig. S2A).

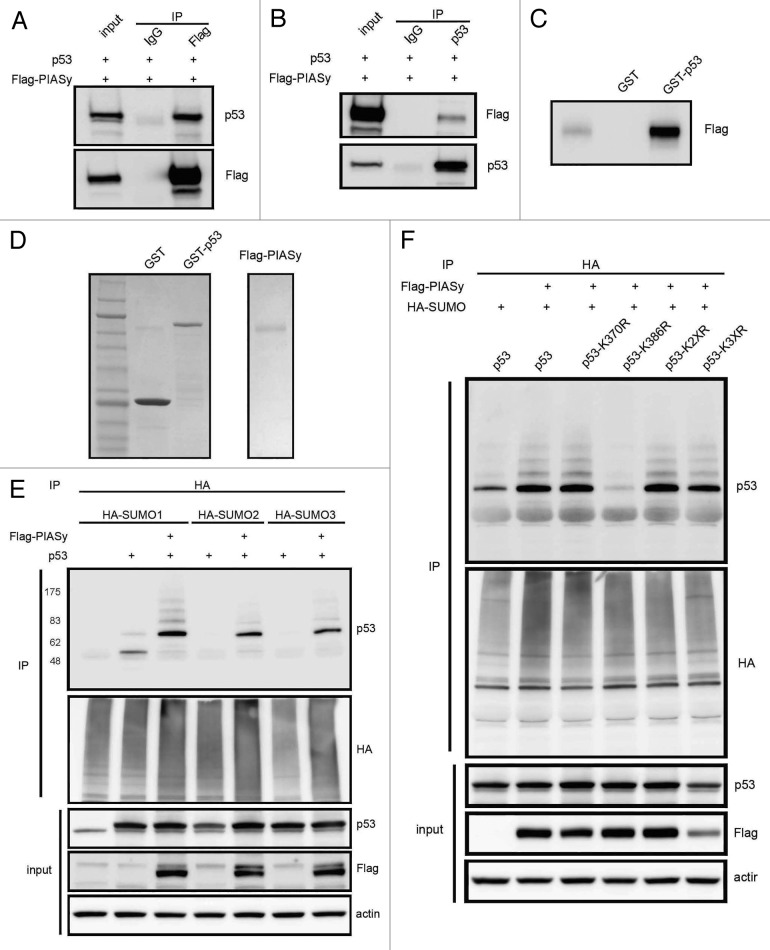

PIASy complexes with p53 in vivo,31 but this interaction is not fully characterized. To confirm PIASy association with p53, RPE1 cells were transfected with Flag-PIASy and p53 plasmids. The Flag antibody co-precipitated p53, and p53 antibody efficiently pulled down Flag-PIASy protein (Fig. 5A and B). Furthermore, bacterially expressed and purified GST-p53 bound to Flag-PIASy protein (Fig. 5C and D), thus establishing physical association of these two proteins.

Figure 5. PIASy complexes with and sumoylates p53. (A and B) RPE1 cells transfected with Flag-PIASy and Tip60 were immunoprecipitated with Flag or p53 antibodies and western blotted with indicated antibodies. (C) In vitro binding assay using the proteins from (D) showing Flag-PIASy binds to GST-p53. (E) PIASy induces sumoylation of p53 as detected by western blot with HA antibodies. The slower migrating bands are most prominent with SUMO1 (F). Lysine 386 is necessary for sumoylation of p53 induced by PIASy.

We then examined the ability of PIASy to sumoylate p53. HA-tagged SUMO-1, -2 or -3 and PIASy together with p53 were expressed in RPE1 cells. Denatured total sumoylated proteins were captured on anti-HA beads and probed with p53 antibody by immunoblot. PIASy promoted high levels of SUMO1 conjugation to p53 compared with SUMO2 and SUMO3 (Fig. 5E). To map the sumoylation site on p53, several C-terminal p53 mutants, including one with a mutation in the predicted SUMO consensus site, were tested. Only p53 K386R failed to become sumoylated in the presence of PIASy (Fig. 5F). This site has been shown to be the target of sumoylation by Ubc9 and PIAS1. Because p53 protein undergoes extensive ubiquitin modification, we reasoned that the faint bands that appear above sumoylated p53 are monoubiquitinated form of this protein. To confirm these findings with endogenous p53 protein, HCT116 cells were transfected with HA-SUMO, exposed to etoposide and p53 immunoprecipitated. Blotting with anti-HA antibody revealed increased sumoylation of endogenous p53 (Fig. S2B).

p53 K120 acetylation and 386 sumoylation are separable.

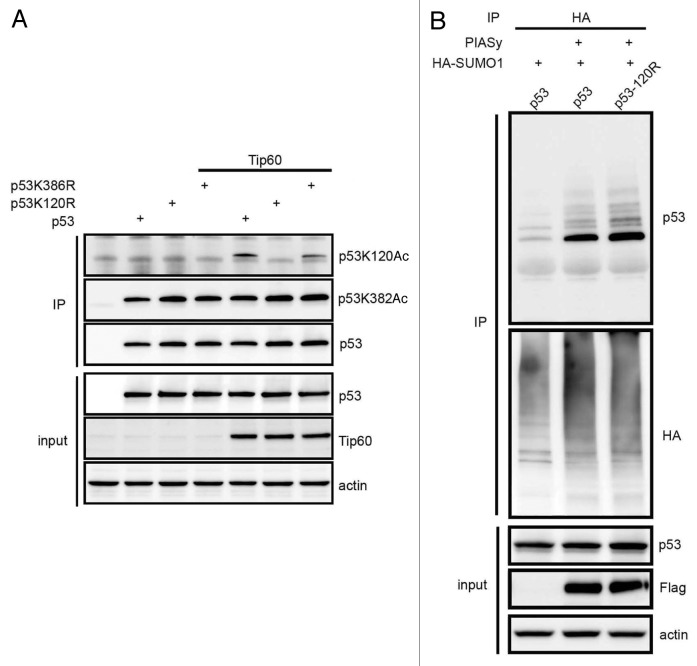

Because p53 K120 is a target of Tip60 and PIASy sumoylates these two proteins, we opted to test whether K120 acetylation and K386 sumoylation modifications are dependent on each other. H1299 cells were transfected with p53, K120R and K386R mutant in the presence and absence of Tip60. Total p53 captured on anti-p53 antibody beads were blotted with acetyl-K120, acetyl-K382 and p53 antibodies. The results showed that Tip60 promoted acetylation of K386R to levels similar to wild type p53, but, as expected, K120R was not acetylated (Fig. 6A). Under these conditions, there was no change in K382 acetylation of p53 and the K120 and K386 mutants. To examine whether p53 K120 acetylation is required for K386 sumoylation, RPE cells were transfected with p53 and K120R in the presence of PIASy. The result showed that PIASy-dependent sumoylation in K120R was unaltered, suggesting K120 acetylation was not required for K386 sumoylation (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. p53 K120 acetylation and K386-sumoylation are not dependent on each other. (A) H1299 cells were transfected with p53 or its mutants, K120R or K386R in the presence or absence of Tip60, the total p53 immunoprecipitate and the input extracts were blotted with indicated antibodies. (B) RPE1 cells transfected with p53 or p53 K120R mutant in the presence of PIASy were tested for SUMO conjugation.

PIASy regulates Tip60-mediated p53 K120 acetylation and apoptosis.

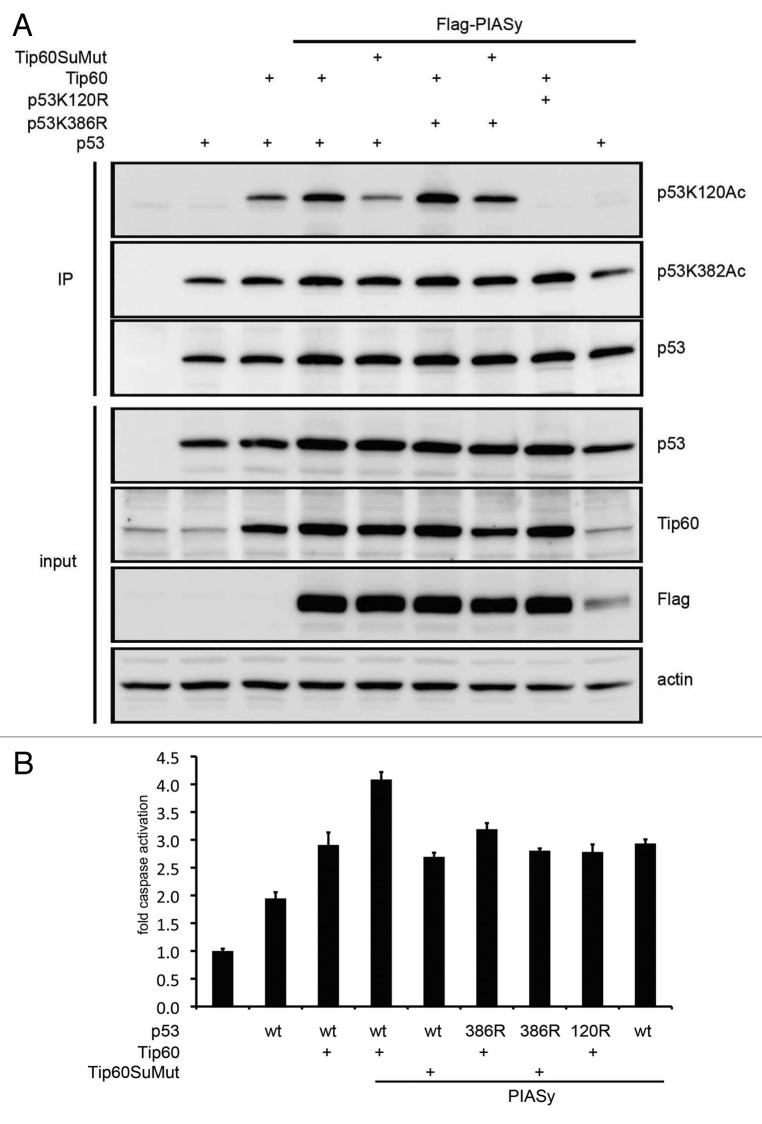

Tip60 regulates p53-induced apoptosis via K120 acetylation. Because PIASy promotes the response to double-stranded DNA breaks,47,48 and our biochemical analysis showed that PIASy stimulates Tip60 sumoylation, we hypothesized that PIASy’s actions on Tip60 would enhance p53 K120 acetylation. To test this hypothesis, we introduced p53 or the lysine mutants together with the sumoylation-defective double mutant of Tip60 (Tip60SuMut) and PIASy into H1299 cells. p53 K120 acetylation was detected upon Tip60 expression, and PIASy enhanced this acetylation (Fig. 7A). Importantly, p53 K120 acetylation was reduced when PIASy was co-expressed with Tip60SuMut. A similar reduction in K120 acetylation was observed with p53 K386R. PIASy alone did not induce p53 K120 acetylation, nor was there any detectable change in p53 K382 acetylation. To examine the biological consequences of PIASy-mediated Tip60 actions on p53, H1299 cells were transfected as above, and apoptosis was assessed. Transfection of p53 resulted in a 2-fold increase in caspase activation, and addition of Tip60 increased the activation to 3-fold (Fig. 7B). Remarkably, a 4-fold caspase activation was recorded with further inclusion of PIASy, and this enhanced caspase activation was reduced by Tip60SuMut. As expected, p53 mutants K386R and K120R showed similar levels of caspase activation.

Figure 7. Sumoylation defective Tip60 fails to respond to PIASy induced p53 K120 acetylation and apoptosis. (A) H1299 cells co-transfected with wild-type, K120R, or K386R p53 and Tip60 or its SUMO-mutant, and the immunoprecipitates were blotted with the indicated antibodies. The top panel shows reduced K120 acetylation with the Tip60 sumoylation mutant with expression of PIASy. (B) H1299 cells were transfected as in (A) and the apoptotic response analyzed using Caspase Glo reagent in three independent transfections. Error bars represent standard error.

Discussion

The p53 protein receives and coordinates multiple stress signals to eliminate cells that have undergone acute DNA damage. Malignant cells frequently encode p53 mutations that circumvent its tumor-restrictive function. However, in nearly half of all cancers, p53 gene is not mutated. Here we show that the SUMO E3 ligase PIASy (PIAS4) complexes with Tip60 and p53 and targets these proteins for sumoylation. This sumoylation enhances Tip60 acetylase activity on p53 lysine 120. The K120-acetylated and K386-sumoylated p53 displayed increased cytoplasmic localization that promoted autophagy. Although these two modifications are not dependent on each other, combination of both is critical for enhanced cytoplasmic localization and autophagy induction. We infer that, similar to silencing of p14ARF, abrogation of this upstream pathway would mitigate selective pressure for inactivating p53 mutations in tumor cells that express wt p53.

Multiple posttranslational modifications induced by DNA damage regulate the transcriptional activity of p53. Results presented here exemplify how genotoxic stress signals are conveyed to p53 via specific yet reversible covalent modifications. In response to double-strand DNA breaks, PIASy stimulates BRCA1 sumoylation to recruit DNA repair proteins.48 Among the members of the PIAS family, PIASy mediates p53-dependent apoptosis and senescence in a SUMO E3 ligase activity-dependent manner.31 Because Tip60 plays a critical role in apoptosis, these findings prompted demonstration of the PIASy interaction withTip60. PIASy sumoylates Tip60 on two SUMO consensus sites located in its C-terminal MYST domain. Mutation of both these lysines prevented sumoylation. It is possible that each sumoylation site responds to a distinct stress signal. Another possibility is that the evolutionarily conserved sumoylation site K451 represents the cognate sumoylation residue (Fig. S3), while K430 undergoes another posttranslational modification. It is important to recognize that lysine-to-arginine mutations on both SUMO consensus sites retain basal histone acetyl transferase activity, implying that these mutations do not impact the basal KAT activity of Tip60. PIASy-mediated SUMO modification enhances Tip60 KAT activity on p53 K120. However, the double SUMO site mutant of Tip60 was unresponsive to PIASy, as it failed to induce p53 K120 acetylation and apoptosis. Maximal p53 K120 acetylation correlated with the apoptotic response when the cells received PIASy, Tip60 and p53. Even though PIASy stimulated Tip60-induced p53 K120 acetylation of wt-p53 as well as p53 K386R, the latter showed an apoptotic response that was equivalent to p53 K120R. One can envision a scenario in which K120 acetylation without K386 sumoylation can recruit p53 to a set of target promoters, and K386 sumoylation without K120 acetylation could have an alternative function. Otherwise, sumoylation may simply unlock p53 from proapototic promoters and facilitate nuclear export of this K120-acetylated p53 to induce autophagy.

Recently it was reported that glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK‑3) phosphorylates Tip60 and stimulates PUMA expression.51 Paradoxically, phosphorylation of Tip60 by GSK-3 occurs in the absence of DNA damage, and its precise role in Tip60 activation remains uncertain. Regulation of GSK-3 is more complex, as GSK-3-mediated phosphorylation of oncoprotein MafA enhances its transformation activity.52 Moreover, inhibition of GSK-3 in melanoma cells promoted apoptosis,53,54 suggesting that GSK-3 regulation of Tip60 may be cell type-specific.

PUMA functions through BAX to promote mitochondrial-selective autophagy.55 Because PUMA is a direct target of p53, it can be argued that p53-mediated autophagy is a partial response to PUMA activation. To address this question, we used HCT116 isogenic PUMA- or p53-null cells. Activation of p53 induced autophagy in PUMA-null cells but not in p53-null cells. Therefore, p53-induced autophagy does not require PUMA induction. DRAM is a modulator of autophagy and another transcriptional target of p53.14,56 Our analysis of DRAM induction in HCT116 cells showed that p53-dependent DRAM induction occurs 24 h after etoposide treatment (Fig. S4), whereas we observed autophagy in less than 12 h. We believe PUMA-independent autophagy induced by activated p53 precedes DRAM activation. Having established PUMA-independent autophagy induction by p53, we next probed the interplay of p53 K120R and K386R mutations for this activity. Although, p53 K120R and K386R mutants induced mdm2 expression similar to wt-p53, these were unable to induce LC3 conversion in p53-null Saos2 cells. This autophagy induction correlated with cell growth inhibition by wt-p53, whereas K120R and K386R failed to inhibit the cell growth. In agreement with these observations, depletion of endogenous Tip60 and PIASy inhibited p53-mediated autophagy in PUMA-null cells (Fig. S5A and B). Collectively, these data suggest that p53 K120 and K386 play a critical role in PUMA-independent autophagy induction by p53.

Although a battery of transcriptional targets of p53 play key roles in the tumor-suppressor function of p53,13,22,39 the interplay among multiple posttranslational has not been deciphered. In fact, in vivo studies demonstrated that transcription-defective p53 retained tumor-suppressor function.37,41 We propose that transcription-associated p53 modifications, such as K120 acetylation and K386 sumoylation, also exert a cytoplasmic function. p53 immunofluorescence and biochemical fractionation show that mutation of K120 or K386 compromised its cytoplasmic localization. These results are consistent with two independent studies showing compromised cytoplasmic accumulation of these mutants.39,57 In agreement with these observations, inhibition of endogenous p53 nuclear export blocked autophagy. Even though how these p53 modifications collaborate with autophagy components remains unclear, we suspect that K120-acetylated and K386-sumoylated p53 reaches the nuclear pore complex, where it is desumoylated prior to nuclear export, and possibly K120-acetylated p53 targets mitochondria to induce autophagy.57 Therefore, combinatorial contributions of these p53 modifications are crucial to execute a rapid cell death response (apoptosis and autophagy) by recycling the p53 molecule that was originally used for nuclear transcription.

These results lead us to propose that PIASy sumoylation stimulates Tip60 activity toward p53, leading to K120 acetylation. PIASy also promotes p53 sumoylation, resulting in a “binary death signal” that is not only linked to p53 transcription function, but also to cytoplasmic accumulation and autophagy. Given the dynamic nature of sumoylation,58 a targeted therapy aimed at stabilizing sumoylation and p53 activation may be a promising strategy for treatment of malignancies that maintain wt-p53.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and antibodies.

Tip60 single and double sumoylation-defective mutations and p53 K120R and K386R mutations were introduced using PCR. To construct GST fusion proteins, Tip60 or p53 coding regions were amplified and cloned into a GST plasmid. HA-SUMO-1, -2 and -3 plasmids are described elsewhere.59 Antibodies to p53, Do-1 (Santa Cruz Biotech), K120-acetyl (Abcam), K382-acetyl (Cell Signaling), anti-Tip60 (Upstate and Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-PIASy (Abgent and Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-PUMA (Anaspec) were purchased and used according to the manufacturers’ recommendations.

Immunoprecipitation.

RPE1 cells were treated with MG132, and the total cell extracts were prepared by adding immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer [50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 125 mM KCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM Na-orthovanadate, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] to cells with brief sonication. Lysates were incubated with corresponding antibodies along with Protein A/G Sepharose. Immunoprecipitate was washed with IP buffer and resolved on acrylamide-SDS gels. For GST pull-down assays, proteins purified from the bacterial extract or mammalian cells followed by benzonase treatment were incubated in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT at 4°C for 2 h and washed before resolving the GST-bound protein on acrylamide-SDS gels.

Sumoylation assay.

Total sumoylated proteins were obtained by adding buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.5% SDS directly to cells. SDS in this extract was diluted to 0.25% before a brief sonication followed by a heat denaturation at 95°C for 2 min and cleared by centrifugation. SDS was further diluted to 0.1% and incubated with HA antibodies to capture sumoylated proteins. Total sumoylated proteins were resolved on a SDS PAGE and blotted with antibodies to Tip60 or p53.

Immunofluorescence and cell fractionation.

Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked (2% BSA in PBS); staining was performed with p53 Do-1 and visualized with anti-mouse-Alexa488. Transfected cells were subjected to cell fractionation for isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierice).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Baehrecke for the discussion on autophagy and Sara Poirier for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by R01 CA107394.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DRAM

damage-regulated autophagy modulator

- KAT

lysine acetyl transferase

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

- PIAS

protein inhibitor of activated STAT

- PUMA

p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here:

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21091

References

- 1.Vousden KH, Lane DP. p53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:275–83. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:909–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zilfou JT, Lowe SW. Tumor suppressive functions of p53. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001883. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo D, Lu H. Nucleostemin: Another nucleolar “Twister” of the p53-MDM2 loop. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3227–32. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benchimol S. p53--an examination of sibling support in apoptosis control. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks CL, Gu W. Ubiquitination, phosphorylation and acetylation: the molecular basis for p53 regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:164–71. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi D, Pop MS, Kulikov R, Love IM, Kung AL, Grossman SR. CBP and p300 are cytoplasmic E4 polyubiquitin ligases for p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16275–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904305106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Jiang X, Chen S, Fernandes N, Price BD. A role for the Tip60 histone acetyltransferase in the acetylation and activation of ATM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504211102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Y, Luo J, Zhang W, Gu W. Tip60-dependent acetylation of p53 modulates the decision between cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2006;24:827–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sykes SM, Mellert HS, Holbert MA, Li K, Marmorstein R, Lane WS, et al. Acetylation of the p53 DNA-binding domain regulates apoptosis induction. Mol Cell. 2006;24:841–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berns K, Hijmans EM, Mullenders J, Brummelkamp TR, Velds A, Heimerikx M, et al. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature. 2004;428:431–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorrini C, Squatrito M, Luise C, Syed N, Perna D, Wark L, et al. Tip60 is a haplo insufficient tumour suppressor required for an oncogene-induced DNA damage response. Nature. 2007;448:1063–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O’Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:121–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chipuk JE, Fisher JC, Dillon CP, Kriwacki RW, Kuwana T, Green DR. Mechanism of apoptosis induction by inhibition of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808036105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chipuk JE, Green DR. How do BCL-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemann MT, Lowe SW. The p53-Bcl-2 connection. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1256–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science. 2005;309:1732–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine B, Abrams J. p53: The Janus of autophagy? Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:637–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb0608-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budanov AV, Karin M. p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell. 2008;134:451–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barré B, Perkins ND. The Skp2 promoter integrates signaling through the NF-kappaB, p53, and Akt/GSK3beta pathways to regulate autophagy and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2010;38:524–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Y, Zhao W, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Gu W. Acetylation is indispensable for p53 activation. Cell. 2008;133:612–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renner F, Moreno R, Schmitz ML. SUMOylation-dependent localization of IKKepsilon in PML nuclear bodies is essential for protection against DNA-damage-triggered cell death. Mol Cell. 2010;37:503–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCool K, Miyamoto S. A PAR-SUMOnious mechanism of NEMO activation. Mol Cell. 2009;36:349–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergink S, Jentsch S. Principles of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications in DNA repair. Nature. 2009;458:461–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang TT, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Wu ZH, Miyamoto S. Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKgamma by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-kappaB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell. 2003;115:565–76. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00895-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palancade B, Doye V. Sumoylating and desumoylating enzymes at nuclear pores: underpinning their unexpected duties? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:174–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gostissa M, Hengstermann A, Fogal V, Sandy P, Schwarz SE, Scheffner M, et al. Activation of p53 by conjugation to the ubiquitin-like protein SUMO-1. EMBO J. 1999;18:6462–71. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu SY, Chiang CM. Crosstalk between sumoylation and acetylation regulates p53-dependent chromatin transcription and DNA binding. EMBO J. 2009;28:1246–59. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahyo T, Nishida T, Yasuda H. Involvement of PIAS1 in the sumoylation of tumor suppressor p53. Mol Cell. 2001;8:713–8. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bischof O, Schwamborn K, Martin N, Werner A, Sustmann C, Grosschedl R, et al. The E3 SUMO ligase PIASy is a regulator of cellular senescence and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2006;22:783–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez GS, Khan SH, Stommel JM, Wahl GM. p53 regulation by post-translational modification and nuclear retention in response to diverse stresses. Oncogene. 1999;18:7656–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green DR, Kroemer G. Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 2009;458:1127–30. doi: 10.1038/nature07986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaseva AV, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. The transcription-independent mitochondrial p53 program is a major contributor to nutlin-induced apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1711–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haupt Y, Rowan S, Shaulian E, Vousden KH, Oren M. Induction of apoptosis in HeLa cells by trans-activation-deficient p53. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2170–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chipuk JE, Maurer U, Green DR, Schuler M. Pharmacologic activation of p53 elicits Bax-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcription. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:371–81. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caelles C, Helmberg A, Karin M. p53-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcriptional activation of p53-target genes. Nature. 1994;370:220–3. doi: 10.1038/370220a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marchenko ND, Wolff S, Erster S, Becker K, Moll UM. Monoubiquitylation promotes mitochondrial p53 translocation. EMBO J. 2007;26:923–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter S, Bischof O, Dejean A, Vousden KH. C-terminal modifications regulate MDM2 dissociation and nuclear export of p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:428–35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michalak EM, Villunger A, Adams JM, Strasser A. In several cell types tumour suppressor p53 induces apoptosis largely via Puma but Noxa can contribute. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1019–29. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brady CA, Jiang D, Mello SS, Johnson TM, Jarvis LA, Kozak MM, et al. Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell. 2011;145:571–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhoumik A, Singha N, O’Connell MJ, Ronai ZA. Regulation of TIP60 by ATF2 modulates ATM activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17605–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802030200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park JH, Sun XJ, Roeder RG. The SANT domain of p400 ATPase represses acetyltransferase activity and coactivator function of TIP60 in basal p21 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2750–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00804-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattera L, Escaffit F, Pillaire MJ, Selves J, Tyteca S, Hoffmann JS, et al. The p400/Tip60 ratio is critical for colorectal cancer cell proliferation through DNA damage response pathways. Oncogene. 2009;28:1506–17. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tyteca S, Vandromme M, Legube G, Chevillard-Briet M, Trouche D. Tip60 and p400 are both required for UV-induced apoptosis but play antagonistic roles in cell cycle progression. EMBO J. 2006;25:1680–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sho T, Tsukiyama T, Sato T, Kondo T, Cheng J, Saku T, et al. TRIM29 negatively regulates p53 via inhibition of Tip60. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1245–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galanty Y, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Polo S, Miller KM, Jackson SP. Mammalian SUMO E3-ligases PIAS1 and PIAS4 promote responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2009;462:935–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris JR, Boutell C, Keppler M, Densham R, Weekes D, Alamshah A, et al. The SUMO modification pathway is involved in the BRCA1 response to genotoxic stress. Nature. 2009;462:886–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X, Ko LJ, Jayaraman L, Prives C. p53 levels, functional domains, and DNA damage determine the extent of the apoptotic response of tumor cells. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2438–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng Z, Ke Y, Ding X, Wang F, Wang H, Wang W, et al. Functional characterization of TIP60 sumoylation in UV-irradiated DNA damage response. Oncogene. 2008;27:931–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charvet C, Wissler M, Brauns-Schubert P, Wang SJ, Tang Y, Sigloch FC, et al. Phosphorylation of Tip60 by GSK-3 determines the induction of PUMA and apoptosis by p53. Mol Cell. 2011;42:584–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rocques N, Abou Zeid N, Sii-Felice K, Lecoin L, Felder-Schmittbuhl MP, Eychène A, et al. GSK-3-mediated phosphorylation enhances Maf-transforming activity. Mol Cell. 2007;28:584–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panka DJ, Cho DC, Atkins MB, Mier JW. GSK-3beta inhibition enhances sorafenib-induced apoptosis in melanoma cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:726–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smalley KS, Contractor R, Haass NK, Kulp AN, Atilla-Gokcumen GE, Williams DS, et al. An organometallic protein kinase inhibitor pharmacologically activates p53 and induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:209–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yee KS, Wilkinson S, James J, Ryan KM, Vousden KH. PUMA- and Bax-induced autophagy contributes to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1135–45. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crighton D, Wilkinson S, Ryan KM. DRAM links autophagy to p53 and programmed cell death. Autophagy. 2007;3:72–4. doi: 10.4161/auto.3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sykes SM, Stanek TJ, Frank A, Murphy ME, McMahon SB. Acetylation of the DNA binding domain regulates transcription-independent apoptosis by p53. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20197–205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeh ET. SUMOylation and De-SUMOylation: wrestling with life’s processes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8223–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gong L, Yeh ET. Characterization of a family of nucleolar SUMO-specific proteases with preference for SUMO-2 or SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15869–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.