Abstract

In 2000, representatives of the transplant community convened for a meeting on living donation in an effort to provide recommendations to promote the welfare of living donors. One key recommendation included in the consensus statement was that all transplant centers which have performed living donor surgeries have an Independent Living Donor Advocate (ILDA) “whose only focus is on the best interest of the donor.” The aims of this study were to begin to understand the sociodemographic characteristics, selection and training, and clinical practices of ILDAs. All U.S. transplant centers performing living donor surgeries were contacted to identify the ILDA at their center. One hundred and twenty ILDAs (60%) completed an anonymous survey. Results indicated considerable variability with regard to the sociodemographic characteristics of ILDAs, how the ILDA was selected and trained, and the ILDAs’ clinical practices, particularly ethical challenges encountered by ILDAs. The variability observed may result in differential selection of donors and could have a potential negative impact the lives of both donors and transplant candidates. The variability in the background, training, and practice of ILDAs suggests the need for strategies, such as practice guidelines, to standardize the interaction between ILDAs and living donors.

Introduction

The inadequate supply of organs in the United States and other countries continues to drive living donor transplantation.1 In 2000, representatives of the transplant community convened for a meeting on living donation in an effort to provide guidelines to promote the welfare of living donors.2 The consensus statement that resulted from this meeting recommended that transplant centers retain an Independent Living Donor Advocate (ILDA) whose primary focus be on the best interest of the donor.2 A decade later, nearly every transplant center in the United States performing living donor surgeries has incorporated an ILDA into their living donor screening and/or evaluation process.

In 2007, the Department of Health and Human Services and United Network for Organ Sharing provided a description of this position and outlined the professional boundaries and responsibilities of ILDAs.3–4 According to the Department of Health and Human Services, the ILDA’s role is to ensure the protection of current and prospective living donors. The Department of Health and Human Services also suggests that the ILDA be knowledgeable about living organ donation, transplantation, medical ethics, and the informed consent process. Recommendations also included that the ILDA not be involved in transplantation activities on a routine basis and that the role should include representing and advising the donor, protecting and promoting the interests of the donor, respecting the donor’s decision, and ensuring that the donor’s decision is informed and free of coercion3.

The United Network for Organ Sharing also changed its bylaws the same year and included the following modifications: (1) all transplant centers must have an ILDA who is not involved with potential recipient evaluation on a routine basis, (2) the ILDA should be independent of the decision to transplant the potential recipient, and (3) the ILDA should be a knowledgeable advocate for the potential living donor.4 According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, the responsibilities of the ILDA are to advocate for potential living donors; promote their best interests; and to assist the potential living donor in obtaining and understanding the consent and evaluation process, surgical procedures, and the benefit and need for post-surgical follow-up.4

Despite the requirements set forth by the Department of Health and Human Services and the United Network for Organ Sharing, and the associated costs for ILDAs (approximately 9 million dollars annually),3 the sociodemographic characteristics, selection and training, and clinical practices of ILDAs are not well understood. The aims of this study were to understand the ILDAs’ background, roles and clinical responsibilities, and how ethical challenges encountered by ILDAs are managed.

Methods

Design

The study was a cross-sectional survey of ILDAs at transplant centers performing living donor surgeries in the United States.

Participants

Each of the 201 transplant centers in the United States that perform living donor surgeries was contacted to identify the ILDA at their center.

Instrument

The survey included 63 quantitative and qualitative items that queried the ILDA with regard to sociodemographic information (e.g., age, gender, education), roles and responsibilities (e.g., number of hours worked, timing of contact with donors), and ethical challenges associated with living donor advocacy (e.g., descriptions of when the ILDA felt as though the donor was being pressured or coerced). See Appendix for survey items.

Procedure

The study commenced after receiving Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Pittsburgh. Between August and October of 2010, all transplant centers performing adult living donor surgeries were contacted, and the ILDA of that center was identified. If we were unable to reach the ILDA or the living donor nurse coordinator, three follow up calls were made over a four week period to contact a member of the living donor transplant team to identify the ILDA at their center. If an ILDA was identified, s/he was requested to provide their email address and the informed consent and survey were sent to the ILDA for completion. The informed consent explained that the survey responses would be returned anonymously to the study team. After the initial email was sent to all ILDAs, three email reminders were sent out over the course of three months to request the ILDA to complete the survey (January-March 2011), and the study closed in March 2011.

Data Analyses

The data were entered into PASW® version 18 and verified. Descriptive statistics were performed (e.g., means, medians, standard deviations) to describe the demographics and practices of the ILDAs. Qualitative data was reviewed for identifying information and removed to protect the confidentiality of donors, ILDAs, and transplant centers. Thematic coding was performed to develop categories for the qualitatitive responses given by the ILDAs for each question.5 Two independent raters coded the ILDA responses and agreement between raters was greater than 80% (82–86%). A consensus by the independent raters was reached on all responses prior to inclusion of data in the final results and categories were not mutually exclusive.

Results

Of the 201 transplant centers performing living donor surgeries, 175 ILDAs (88%) were identified and provided their email addresses. Twelve (6%) of the transplant centers did not return the study team’s call after three attempts to reach them by phone, and three centers (2%) reported that they did not have an ILDA. Four ILDAs (2%) who were contacted were not interested in participating, two ILDAs (<1%) reported that their hospital prohibited them from participating in the study, two ILDAs (<1%) provided services for four transplant centers, and one ILDA was excluded (PI of the study). Of the 175 ILDAs who were sent the survey by email, 120 (69%) completed and returned the survey.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the ILDAs

Of the 120 ILDAs who completed the survey, 82.5% were female, and the mean age was 49.2 ± 10 years. The majority of ILDAs were Caucasian (83.1%) followed by African-American (5.1%), American Indian/Native Alaskan (4.2%), Hispanic/Latino (3.4%), Asian-American (2.5%), and other (1.7%). Nursing was the primary discipline (35.8%), followed by social work (33%), clergy (13.2%), psychology (3.8%), and other disciplines (14.2%). Table 1 provides further details regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the ILDAs.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of ILDAs

| Gender (n, %) | |

| Male | 21 (17.5) |

| Female | 99 (82.5) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.17 (9.96) |

| Range | 25–74 |

| Race/Ethnic Background (n, %) | |

| White | 98 (83.1) |

| Black | 6 (5.1) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 (4.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (3.4) |

| Asian | 3 (2.5) |

| Other | 2 (1.7) |

| Education Level (n, %) | |

| High School or less | 1 (0.8) |

| Associate’s Degree | 6 (5.0) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 33 (27.5) |

| Master’s Degree | 66 (55.0) |

| Doctorate | 9 (7.5) |

| MD/DO | 4 (3.3) |

| Other | 7 (5.8) |

| Professional Training/Discipline (n, %) | |

| Nursing | 38 (35.8) |

| Social Work | 35 (33.0) |

| Clergy | 14 (13.2) |

| Psychology | 4 (3.8) |

| Other | 15 (14.2) |

Defining the Role and Responsibility of the “Independent” LDA

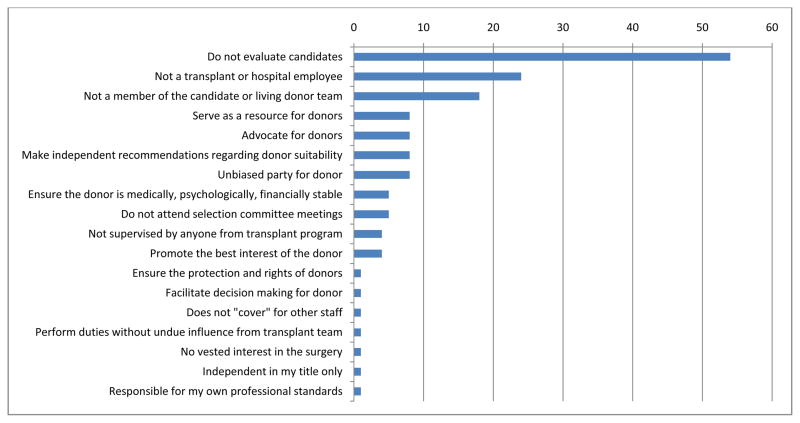

The ILDAs were asked to define “independent” as it refers to their role as an “Independent” Living Donor Advocate (ILDA). The majorty of ILDAs (54%) reported that “independent” referred to the ILDA not evaluating transplant candidates. The remaining ILDAs reported that “independent” referred to: not being a transplant or hospital employee (24%); not being a member of the candidate or living donor teams (18%); serving as a resource for donors (8%); advocating for donors (8% ); making independent recommendations regarding the donor (8%); being an unbiased party for the donor (8%); assuring the medical, psychological and financial stability of the donor (5%); not attending the selection committee meetings (5%); not being supervised by anyone from the transplant team (4%); promoting the best interest of the donor (4%); ensuring the protection and rights of the donor (1%); facilitating decision making for the donor (1%); not covering for other staff (1%); performing duties without undue influence from the transplant team (1%); having no vested interest in the surgery (1%); the term is independent is in my title only (1%); and being responsible for my own professional standards (1%; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percent of ILDAs describing their roles and responsibilitiesas an ILDA

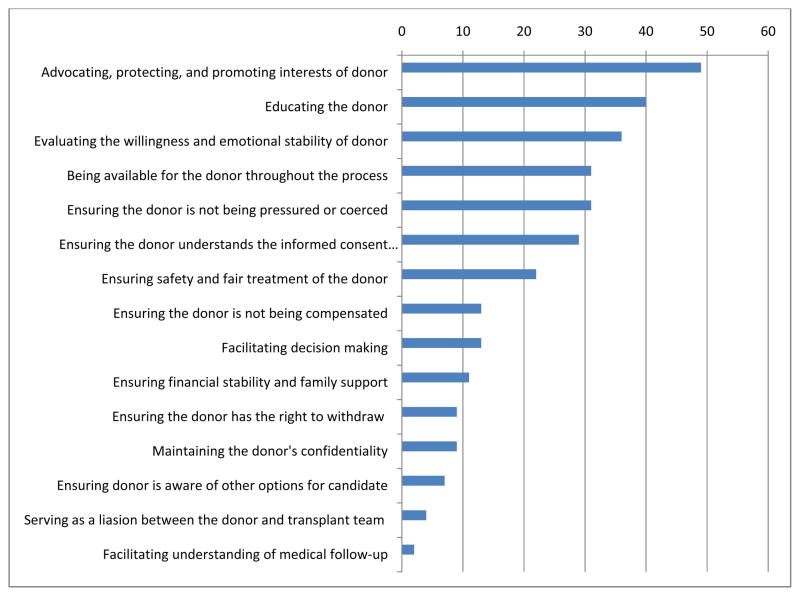

The ILDAs, when queried to describe their responsibilities as an ILDA, reported a wide range of duties including: advocating, protecting, and promoting the best interest of the donor (49%); educating the donor (40%); evaluating the willingness and emotional stability of the donor (36%); being available throughout the process (31%); assuring the donor is not being pressure or coerced (31%); ensuring the donor understands the informed consent process (29%); ensuring safety and fair treatment of the donor (22%); ensuring the donor is not being compensated (13%); facilitating decision making with the donor (13%); ensuring financial stability and family support (11%); ensuring the donor has the right to withdraw (9%); maintaining the donors confidentiality (9%); ensuring the donor is aware of other options for the candidate (7%); serving as a liaison between the donor and transplant team (4%); and facilitating understanding of medical follow-up (2%; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percent of ILDA reporting their definition of “Independent”

According to the governing bodies, the role of the ILDA has been described as one that should both “protect” and “advocate” for the donor. The ILDAs were queried about how they would proceed with regard to the following scenario:

“How would you proceed if you felt that the donor having surgery would be detrimental to their physical or psychological well being, but (1) this had been explained to the donor in detail and the donor understood the potential consequences; (2) the donor has been approved to proceed with surgery by the medical and psychosocial team members; and (3) the donor wants to proceed with surgery despite the potential risks?”

Twenty-nine percent of ILDAs responded that they would document their concerns but would “approve” the donor for surgery (“advocate”). The majority of ILDAs reported that they would document their concerns and “not approve” the donor for surgery (50.7%; “protect”). The remaining ILDAs (20.3%) had a variety of responses including not being aware they were involved in the selection process.

Selection and Training of the ILDAs

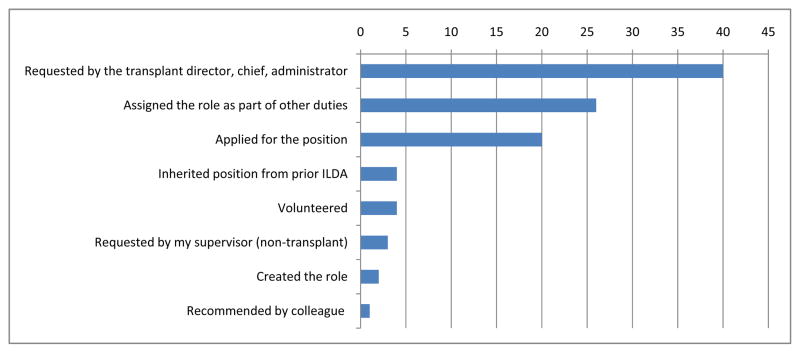

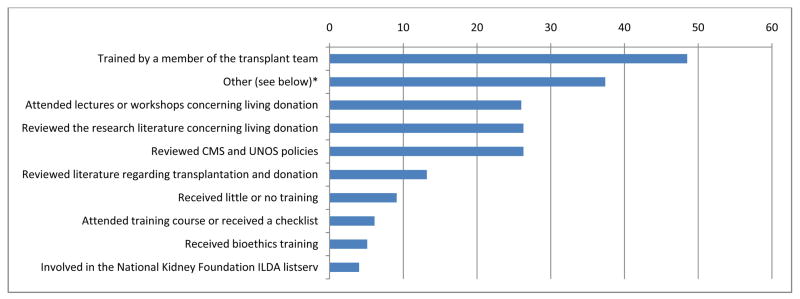

Figure 3 depicts the ILDAs response to how they were selected for the ILDA position at their transplant center. The largest percentage of ILDAs (40%) reported that they were asked by the transplant chief, director, or administrator to become the ILDA. Twenty-six percent reported being assigned the ILDA responsibilities as apart of other duties (e.g., social work, nursing); 20% reported that they applied for the position; and the remaining ILDAs (14%) reported other methods of becoming the ILDA at their center (e.g., volunteered, inherited the position, created the role). The ILDAs reported being initially trained as an ILDA by: members of the transplant team (48.5%); other (served on ethics or selection committee, conducted own research, consulted with other health care professionals, or learned from patients and families; 37.4%); attended lectures at conferences (26%); reviewed the research literature (26.3); reviewed CMS and UNOS policies (26.3%); reviewed the transplant literature (13.2%); received little or no training (9.1%); attended a training course or received checklist (6.1%); received training in bioethics (5.1%); or involved with the National Kidney Foundation listserv (4%; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Percent of ILDAs reporting how they were selected as the ILDA at their transplantcenter

Figure 4. Percentage of ILDAs reporting how they were trained as an ILDA.

Other=serve on ethics or selection committee, own research and writing, consult with other health care professionals, learned from patients and families

Clinical Practice of ILDAs

Table 2 provides details regarding the clinical practices of ILDAs (e.g., number and types of donors evaluated). A large percentage of ILDAs combined their ILDA evaluation with another role and set of responsibilities (53.4%). With regard to the salary for the ILDA, 41% of ILDAs reported being paid by the transplant center, while 47% were paid by other sources (e.g., hospital), and 5.9% of ILDAs were volunteers. Few ILDAs reported billing for their services (14.5%). Recent recommendations from UNOS include that the living donor team encourages donors to undergo a physical exam and blood tests for a minimum of 2 years after donation. The majority of ILDAs reported that they followed donors for less than one year. At this time, ILDAs are not required to follow donors as part of these recommendations by UNOS to have donors evaluated medically for a 2 year period post-surgery.

Table 2.

ILDA Practices

| Number of Working Hours/Week | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.43 (16.59) |

| Range | 0.25–70 |

| Type of Evaluations Performed (n, %) | |

| LDA Evaluation Only | 49 (47.6) |

| LDA and Psychosocial/Social Work Evaluation | 55 (53.4) |

| Job Responsibilities (n, %) | |

| Full time LDA and Additional Duties | 73 (71.6) |

| LDA only | 29 (28.4) |

| Position Paid or Volunteer (n, %) | |

| Paid and hired by transplant center | 35 (41.2) |

| Volunteer | 5 (5.9) |

| Paid but part of other responsibilities | 40 (47.1) |

| Other | 6 (7.1) |

| Donors Evaluated (n, %) | |

| Kidney | 86 (100.0) |

| Liver | 15 (17.4) |

| Lung | 2 (2.3) |

| Pancreas | 1 (1.2) |

| Intestine | 2 (2.3) |

| Timing of Contact (n, %) | |

| Screening | 38 (45.2) |

| Evaluation | 67 (79.8) |

| Post-evaluation/prior to surgery | 49 (58.3) |

| Post-surgery | 47 (56.0) |

| ILDA versus ILD Team (n, %) | |

| LDA Team | 41 (40.6) |

| Independent LDA | 60 (59.4) |

| Cooling off Period for Donors (n, %) | |

| None | 20 (30.8) |

| Varies | 15 (23.1) |

| 1–10 days | 8 (12.3) |

| 11–20 days | 11 (16.9) |

| 20–30 days | 7 (10.8) |

| 30+ days | 4 (6.2) |

| Bill for ILDA Evaluations (n, %) | |

| Yes | 12 (14.5) |

| No | 71 (85.5) |

| Length of Follow-up Post Surgery (n, %) | |

| < 6 months | 40 (50.0) |

| 6 m. – 1 yr. | 13 (16.3) |

| 1 yr. – 18 m. | 3 (3.8) |

| 18m. – 2yr. | 10 (12.5) |

| 2yr. or more | 22 (27.5) |

| Modality of Meeting with Donor (n, %) | |

| Individual | 83 (95.4) |

| In group | 1 (1.1) |

| Both individual and group | 4 (4.6) |

| Type of Educational Materials Provided to Donors (n, %) | |

| UNOS | 9 (12.9) |

| AST | 3 (4.3) |

| DVD | 7 (10.0) |

| Center-specific educational materials | 54 (77.1) |

| Donor Signs Document Stating they Understand Risks and are Not Receiving Compensation (n, %) | |

| Yes | 42 (50.6) |

| No | 41 (49.4) |

| Occasionally | 15 (19.5) |

| ILDA Attends Selection Committee Meetings (n, %) | |

| Live Donors Presented | 36 (53.7) |

| Live Donors and Candidates Presented | 26 (38.8) |

| I do not attend | 5 (7.5) |

| Only attend occasionally | 6 (9.0) |

| Access to Donor Medical Record (n, %) | |

| Yes, full access | 65 (84.4) |

| No | 8 (10.4) |

| Yes, limited access | 4 (5.2) |

| Transplant Staff Access to ILDA Evaluation (n, %) | |

| Yes | 69 (90.8) |

| No | 7 (9.2) |

| ILDA Keeps Confidential Notes (n, %) | |

| Yes | 22 (28.9) |

| No | 55 (72.5) |

Most ILDAs reported attending their centers’ multidisciplinary selection committee meetings in which donor (and sometimes transplant) candidates were discussed for suitability for surgery (67.5%). Ninety-one percent reported that other members of the medical team had access to their notes, while 9.2% did not share their evaluation or progress notes with the medical team. Twenty-nine percent of ILDAs reported that they kept separate confidential notes regarding the living donor evaluation or follow-up in addition to the shared reports.

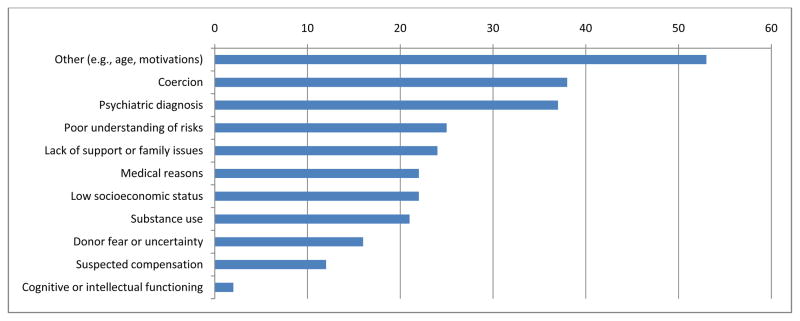

Of those who reported that they were involved in the “selection” process of donors (63%), 16% reported never recommending against donation, while 57.4% reported recommending against donation 1–5 times, 23% recommended against donation between 6–25 times, and 3.3% reported recommending against donation greater than 25 times in their ILDA career. Figure 5 provides ILDAs’ reasons for declining donors from surgery including: other reasons (e.g., age, motivations; 53%); (2) coercion (38%); psychiatric diagnoses (37%); poor understanding of risks (25%); lack of support or family issues (24%); medical reasons (22%); low socioeconomic status (22%); substance use (21%); donor fear or uncertainty (16%); suspected compensation (12%); and cognitive or intellectual functioning (2%).

Figure 5. Percent of ILDAs reporting the reasons for declining donors for surgery.

Other= age, motivations for donation, unstable life, no transportation/insurance, adherence to medical treatments

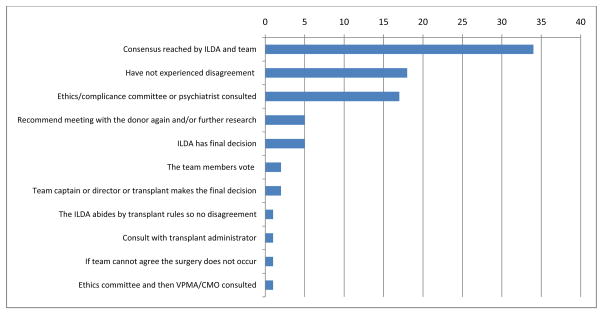

The ILDAs were also queried about how disagreements between the ILDA and transplant team were resolved at their center. Figure 6 shows responses provided by the ILDAs and included: a consensus was reached (34%); have not experienced a disagreement (18%); ethics or compliance committee or psychiatrist consulted (17%); met with the donor a second time and/or performed further research (5%); the ILDA has the final decision (5%); the team members vote (2%); the team captain or director makes the final decision (2%); the ILDA abides by transplant rules so there is no disagreement (1%); consulted with transplant administrator (1%); if the team cannot agree then the surgery does not occur (1%); and the ethics committee and then vice president of medical affairs or chief medical officer was consulted (1%).

Figure 6.

Percentage of ILDAs reporting the variety of methods used to resolve disagreements between the transplant team and ILDA

Nine hypothetical scenarios reflecting potential issues with “valuable consideration” were presented to ILDAs. The following percentage of ILDAs reported that the scenarios in Table 3 were “acceptable” with regard to the receipt of valuable consideration: receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for the flight to be evaluated for donation or for the surgery (7.1%); receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for unemployment benefits lost while recovering from surgery (47.1%); receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for wages lost while recovering from surgery (64.7%); if the transplant candidate is an employer and the donor is the employee, the donor receives from the candidate time off for the surgery and recovery with pay (35.3%); receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for a vacation with the candidate’s family (2.9%); receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for the expenses for lodging and food while being evaluated for donation or surgery (85.3%); receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) to cover the mortgage/rent, car payment, and utilities while recovering from surgery (41.2%); receiving financial assistance up to $5000 from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for expenses related to the donation (25.3%); and receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family ) for the donor’s discretion (2.9%).

Table 3.

ILDA Responses to Hypothetical Scenarios

| Scenarios Considered “Acceptable” | Percent of ILDAs |

|---|---|

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for the flight to be evaluated for donation or for the surgery | 7.1 |

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for unemployment benefits lost while recovering from surgery | 47.1 |

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for wages lost while recovering from surgery | 64.7 |

| If the transplant candidate is an employer and the donor is the employee, the donor receives from the candidate time off for the surgery and recovery with pay. | 35.3 |

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for a vacation with the candidate’s family | 2.9 |

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) for the expenses for lodging and food while being evaluated for donation or surgery | 85.3 |

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family) to cover the mortgage/rent, car payment, and utilities while recovering from surgery | 41.2 |

| Receiving financial assistance up to $5000 from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family)for expenses related to the donation | 25.3 |

| Receiving financial assistance from the transplant candidate (or candidate’s family ) for the donor’s discretion | 2.9 |

Discussion

Despite the fact that nearly every transplant center involved in living donor surgeries has an ILDA, a paucity of information exists regarding the role and responsibilities of the ILDA. This survey describes the ILDAs role and responsibilities in the transplant centers since the conceptualization of this role at the 2000 consensus meeting regarding living donation.2 The findings of this study suggest that there is marked variability in the sociodemographic characteristics, definition of the ILDA role, the clinical practice of ILDAs, and how ILDAs manage ethically challenging issues associated with living donation.

First, there was a range of educational backgrounds of ILDAs (e.g., less than high school diploma to professional degrees); however, the majority of ILDAs reported having a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree and were trained either as nurses or social workers. Rudow-LaPoint reported that one of the most debated issues regarding the ILDA is the issue of “independence”.6 The findings of this survey also suggested ILDAs themselves may have many definitions regarding the term “independent” as it refers to their role as an ILDA. The wide range of definitions may reflect the training and/or the interpretation of his/her role and responsibilities.

No formal training exists at this time for ILDAs and the survey findings suggest that ILDAs have received training from a variety of sources and the type and duration of training varied greatly amongst ILDAs. It is recommended that formal training be available for ILDAs as well as continuing education, as the field of living donation and the guidelines and requirements set forth by the Department of Health and Human Services and the United Network for Organ Sharing, continue to evolve. Because of the diversity of professional backgrounds of ILDAs, it may be a challenge to identify a common forum (e.g., professional meeting) for training and continuing education. Development of written and/or web-based educational materials for ILDAs could be an approach that would facilitate consistency in knowledge and practices across ILDAs.

Approximately half of the ILDAs combined the ILDA evaluation with other responsibilities (e.g., psychosocial, medical, or nursing evaluation). The advantages to combining the ILDA evaluation include a more comprehensive understanding of the donor and family dynamics which in turn can facilitate the decision making process regarding the donors’ suitability for surgery. The disadvantages include the ILDAs’ role becoming diffuse and the ILDA may not be able to “advocate” for the donor if s/he believes that there is a psychosocial, financial, or medical contraindication for surgery.

The educational information the donor receives may be important in his or her decision to proceed with surgery and therefore approved materials should be given to donors. Of the ILDAs who provided educational information to donors, only a minority (<20%) provided information from UNOS or other national organizations related to transplantation.

The majority of ILDAs reported attending multidisciplinary selection committee meetings in which donor, and sometimes transplant, candidates were discussed. The consensus statement published in 2000 suggested that the ILDA should have the power to “veto” the surgery.1 It is clear from the findings of this study that a minority of ILDAs have the power to “veto” the surgery, while some ILDAs were not even aware that this was an option for ILDAs.

If the ILDA is a part of the selection process, the ILDA may be obligated to disclose to the medical team(s) the reasons for recommending against surgery, both verbally and as part of the donor’s medical record. It is unlikely the donors are aware that information disclosed to the ILDA will be shared with the medical team(s). If ILDAs are involved in the selection process, this should be included in the informed consent process so the donors are aware that the information disclosed to the ILDA may be shared with other members of the medical team and the ILDA is involved in the decision for their suitability for surgery. If members of both the donor and candidate transplant teams are present at the selection committee meetings, and the ILDA discloses information discussed with the donor, there may be an increased risk of the donor’s confidentiality may be breached to family members and/or recipients.

Rudow-LaPoint and colleagues suggested that ILDAs be involved in the short-and long-term follow-up of living donors; however, this has fiscal implications for the transplant or medical center supporting the ILDAs. At least for some donors, long-term follow-up may be recommended particularly for those who experienced medical, psychosocial, or financial complications surrounding donation; lose their loved one during or shortly after the transplant, or when the donor may be facing a new medical diagnosis as a result of the donor evaluation process (e.g., cancer, Hepatitis C).

One of the most controversial areas in living donation is “valuable consideration”.7–9 The National Organ Transplantation Act (NOTA, P.L. 98–507) permits living and deceased organ donation but prohibits the sale of organs. Section 301 of NOTA specifically prohibits the exchange of valuable consideration (money or the equivalent) for organs.10 Valuable consideration “does not include the reasonable payments associated with the removal, transportation, implantation, processing, preservation, quality control, and storage of a human organ or the expenses of travel, housing, and lost wages incurred by the donor of a human organ in connection with the donation of the organ.”10 The penalty for such a violation is “a fine not more than $50,000 or imprisonment not more than five years, or both.”10 Because of the potential consequences to the donor if thought to be receiving compensation for donation, the ILDA’s understanding of this law is critical.

The primary limitation of this study was the response rate of the ILDAs to the request to complete this survey; however, the response rate exceeded the rates often obtained in web-based surveys with no incentive.11 The investment and enthusiasm many ILDAs report for their role as an ILDA was reflected in the high rate of participation in this survey.

This survey identified marked variability in the position and practice of the ILDA in transplant centers. Although practice variability exists in all disciplines, many professions have practice guidelines to provide a minimum standard. Practice guidelines are often recommended for legal and regulatory issues, consumer and/or public benefit (e.g., improved service delivery, avoiding harm to the patient, decreasing disparities in underserved or vulnerable populations), and for professional guidance (e.g., risk management issues, advances in practice). Without such practice guidelines there is a possibility that donors (and indirectly, candidates) may be negatively affected through the screening and/or selection process. The ILDAs’ decisions can have a significant impact on a donor (e.g., felony charge for valuable consideration) and/or the transplant candidate (e.g., candidate death). Even though the evaluation of living donors is a multidisciplinary process, the development of uniform practice guidelines for ILDAs is critical for decreasing potential disparities, particularly if the ILDA has “veto” power, as was evidenced by some ILDAs.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- ILDA

Independent Living Donor Advocate

Footnotes

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Support and Financial Disclosure Declaration: National Cancer Institute K07CA118576; K07CA118576-04S1

Contributor Information

Jennifer Steel, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery and Psychiatry.

Andrea Dunlavy, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Maranda Friday, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Kendal Kingsley, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Deborah Brower, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Mark Unruh, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Medicine.

Henkie Tan, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Ron Shapiro, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Mel Peltz, University of Pittsburgh, School of Social Work.

Melissa Hardoby, University of Pittsburgh, School of Social Work.

Christina McCloskey, Seton Hill University, Department of Psychology.

Mark Sturdevant, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

Abhi Humar, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery.

References

- 1.Pomfret EA, Sung RS, Allan J, Kinkhabwala M, Melancon JK, Roberts JP. Solving the Organ Shortage Crisis: The 7th Annual American Society of Transplant Surgeons’ State-of-the-Art Winter Symposium. The American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 8(4):745–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abecassis M, Adams M, Adams P, et al. Consensus statement on the live organ donor. JAMA. 2000;284:2919–2926. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services, Part II. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 42 CFR Parts 405, 482, 488, and 498 Medicare Program; Hospital Conditions of Participation: Requirements for Approval and Re-Approval of Transplant Centers To Perform Organ Transplants; Final Rule Federal Register/Vol. 72, No. 61/Friday, March 30, 2007/Rules and Regulations, 15198–15280.

- 4.United Network for Organ Sharing has also modified its bylaws the same year. Appendix B, Section XIII, 2007.

- 5.Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudow-LaPointe D. Living donor advocate: a team approach to educate, evaluate, and manage donors across the continuum. Progress in Transplant. 2009;9(1):64–70. doi: 10.1177/152692480901900109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaston RS, Danovitch GM, Epstein RA, Kahn JP, Schnitzler MA. Must all living donor compensation be viewed as valuable consideration? American Journal of Transplantation. 7:1309–1310. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaston RS, Danovitch GM, Epstein RA, Kahn JP, Schnitzler MA. Reducing the financial disincentives to living kidney donation: will compensation help the way it is supposed to? Nature Clinical Practice, Nephrology. 3(3):132–133. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Forum on the Care of Live Kidney Donors. A report of the Amsterdam Forum on the care of live kidney donor: Data and medical guidelines. Transplantation. 79(S2):S53–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The National Organ Transplant Act (1984; 98–507), approved October 19, 1984 and amended in 1988 and 1990.

- 11.Sax LJ, Gilmartin SK, Bryant AN. Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Research in Higher Education. 2003;44 (4):409–432. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.