Abstract

The genus The genus Dinemasporium is used as a case study to evaluate the importance of conidial appendages for generic level classification of coelomycetous fungi. Based on morphology and sequence data of the large subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (LSU, 28S) and the internal transcribed spacers and 5.8S rRNA gene of the nrDNA operon, the genus Dinemasporium is circumscribed, and an epitype designated for D. strigosum, the type of the genus. A further five species are introduced in Dinemasporium, namely D. pseudostrigosum (isolated from Triticum aestivum, Germany and Stigmaphyllon sagraeanum, Cuba), D. americana (soil, USA), D. polygonum (Polygonum sachalinense, Netherlands), D. pseudoindicum (soil, USA), and D. morbidum (human sputum, Netherlands and hare dung, New Zealand). Brunneodinemasporium, based on B. brasiliense, is introduced to accommodate Dinemasporium-like species with tightly aggregated brown conidiogenous cells, and pale brown conidia. Dendrophoma (= Amphitiarospora) is reinstated as distinct from Dinemasporium, and an epitype designated for D. cytisporoides, characterised by its superficial, stipitate to cupulate conidiomata, and small conidia with two polar, tubular, exogenous appendages. The genus Stauronema is reduced to synonymy under Dinemasporium. Pseudolachnea (1-septate conidia) is supported as distinct from Dinemasporium (aseptate conidia), and P. fraxini introduced as a novel species. Taxa in this generic complex differ by combination of morphological characters of conidiomata, setae, conidia and appendages. Appendage morphology alone is rejected as informative at the generic level.

Keywords: Chaetosphaeriaceae, Dinemasporium, ITS, LSU, Sordariomycetes, systematics

INTRODUCTION

In his revision of coelomycetous fungi with appendage bearing conidia, Nag Raj (1993) mentioned that in early papers dealing with these fungi, descriptions of novel taxa only rarely referred to the fact that conidia had appendages. In later years, these appendages were seen as taxonomically informative in separating species, especially in genera such as Coniella (van Niekerk et al. 2004), Phyllosticta (Wulandari et al. 2009, Glienke et al. 2011, Wikee et al. 2011), Pestalotiopsis (Maharachchikumbura et al. 2011), Seimatosporium (Barber et al. 2011), and Tiarosporella (Crous et al. 2006). Sutton & Sellar (1966) categorised appendages by their structure and position, whether mucilaginous or cellular, endo- or exogenous, simple or branched, as well as their position on the conidium. Nag Raj (1993) further elaborated on these concepts, and defined nine appendage types (A–I), with three subdivisions for appendage type A. He further highlighted the diversity that exists in appendage morphology, namely in shape (filiform, attenuated or podiform), position (apical, basal, lateral, or in combination), in patterns of distribution on the conidium, in branching, in integrity with the conidium, in sequence of development, and in structural changes (nucleate or not).

Appendages usually relate to an ecological function linked to spore dispersal, and the colonisation of new substrates or niches. Appendages play an important role in spore attachment to substrates to ensure that the conidium can germinate and its hyphae can infect or colonise the substrate (Nag Raj 1993). Conidial appendages are known to occur in coelomycetes in diverse habitats ranging from terrestrial to aquatic. Appendages have subsequently been used to support the combination or separation of taxa into different genera. One such genus is Dinemasporium, which forms the basis of the present study. It is characterised by superficial, cupulate to discoid conidiomata with brown setae, and phialidic conidiogenous cells that give rise to hyaline, oblong to allantoid, aseptate conidia with an appendage at each end.

The genus Dinemasporium has several acknowledged synonyms, namely Dendrophoma, Pycnidiochaeta, and Amphitiarospora (Sutton 1980, Nag Raj 1993). Sutton (1980) placed species with septate conidia in Pseudolachnea, while Nag Raj (1993) separated Pseudolachnea (1-septate conidia) from Pseudolachnella (multiseptate conidia). Saccardo (1884) established the subgenus Stauronema for taxa with conidia that had apical, basal as well as lateral appendages. Sutton (1980) later elevated Stauronema to generic level, a proposal subsequently accepted by Nag Raj (1993).

The aim of the present study is to investigate the taxonomic value of appendages as defining feature at generic level in coelomycetous fungi, by using Dinemasporium as a case study. A further aim is to clarify the phylogenetic position of the genus Dinemasporium, and to revisit its circumscription in relation to its synonyms and closely allied genera, many of which are distinguished by a combination of conidium septation and appendage morphology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates

The majority of the strains used in the present study were obtained from the culture collection of the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre (CBS) Utrecht, the Netherlands. Fresh collections were made from debris of diverse hosts by placing material in damp chambers for 1–2 d. Single conidial colonies were established from sporulating conidiomata on Petri dishes containing 2 % malt extract agar (MEA; Crous et al. 2009b) as described earlier (Crous et al. 1991). Colonies were sub-cultured onto potato-dextrose agar (PDA), oatmeal agar (OA), MEA, and pine needle agar (PNA) (Smith et al. 1996), and incubated at 25 °C under continuous near-ultraviolet light to promote sporulation. Reference strains were deposited at the CBS.

DNA isolation, amplification and analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from fungal colonies growing on MEA using the UltraCleanTM Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Inc., Solana Beach, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers V9G (de Hoog & Gerrits van den Ende 1998) and LR5 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990) were used to amplify part (ITS) of the nuclear rDNA operon spanning the 3′ end of the 18S rRNA gene, the first internal transcribed spacer (ITS1), the 5.8S rRNA gene, the second ITS region and the 5′ end of the 28S rRNA gene. The primers ITS4 (White et al. 1990) and LSU1Fd (Crous et al. 2009a) were used as internal sequence primers to ensure good quality sequences over the entire length of the amplicon. The sequence alignment and subsequent phylogenetic analyses for all the above were carried out using methods described by Crous et al. (2006). Gaps longer than 10 bases were coded as single events for the phylogenetic analyses; the remaining gaps were treated as ‘fifth state’ data. Sequences derived in this study were lodged at GenBank, the alignment in TreeBASE (www.treebase.org/), and taxonomic novelties in MycoBank (www.MycoBank.org; Crous et al. 2004).

Morphology

Morphological descriptions are based on slide preparations mounted in clear lactic acid from colonies sporulating on PNA. Observations were made with a Zeiss V20 Discovery stereo-microscope, and with a Zeiss Axio Imager 2 light microscope using differential interference contrast (DIC) illumination and an AxioCam MRc5 camera and software. Colony characters and pigment production were noted after 1 mo of growth on MEA, PDA and OA (Crous et al. 2009b) incubated at 25 °C. Colony colours (surface and reverse) were rated according to the colour charts of Rayner (1970).

RESULTS

Phylogeny

Amplicons of approximately 1 700 bases were obtained of the ITS region (including the first approximately 900 bp of LSU) for the isolates listed in Table 1. The LSU sequences were used to obtain additional sequences from GenBank, which were added to the alignment (Fig. 1) and the ITS to determine species identification (Fig. 2; discussed in species notes where applicable). The manually adjusted LSU alignment contained 42 sequences (including the outgroup sequence) and 798 characters including alignment gaps (available in TreeBASE) were used in the phylogenetic analysis; 151 of these were parsimony-informative, 136 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 511 were constant. Neighbour-joining analyses using three substitution models on the sequence alignment yielded trees with identical topologies to one another and support the same terminal clades as obtained from the parsimony analysis. The parsimony analysis of the LSU alignment yielded 142 equally most parsimonious trees (TL = 741 steps; CI = 0.533; RI = 0.662; RC = 0.353). The manually adjusted ITS alignment contained 31 sequences (including the outgroup sequence) and 514 characters including alignment gaps (available in TreeBASE) were used in the phylogenetic analysis; 203 of these were parsimony-informative, 60 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 251 were constant. Neighbour-joining analyses using three substitution models on the sequence alignment yielded trees with identical topologies to one another and support the same terminal clades as obtained from the parsimony analysis. The parsimony analysis of the ITS alignment yielded 3 equally most parsimonious trees (TL = 929 steps; CI = 0.553; RI = 0.706; RC = 0.390). All the species treated below are supported as distinct in the ITS phylogeny (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Collection details and GenBank accession numbers of isolates for which novel sequences were generated in this study.

| Species | Strain accession no.1 | Substrate | Country | Collector(s) | GenBank accession no.2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | |||||

| Brunneodinemasporium brasiliense | CBS 112007; INIFAT CO2/51 | Decaying leaf | Brazil | R.F. Castañeda-Ruiz | JQ889272 | JQ889288 |

| Dendrophoma cytisporoides | CBS 223.95 | Branches and twigs of Rhododendron | Netherlands | A. Aptroot | JQ889273 | JQ889289 |

| Dinemasporium americana | CBS 127127; RMF 7507 | A1 horizon soil of tallgrass prairie | USA:Iowa | D.E. Tuthill | JQ889274 | JQ889290 |

| Dinemasporium decipiens | CBS 592.73 | Soil under Elaeis guineensis | Suriname | J.H. van Emde | JQ889275 | JQ889291 |

| Dinemasporium morbidum | CBS 129.66 | Sputum of man | Netherlands | N.G.M. Orie & A. Kikstra | JQ889280 | JQ889296 |

| CBS 995.97; ATCC 200690 | Hare dung | New Zealand | D.P. Mahoney | JQ889281 | JQ889297 | |

| Dinemasporium polygonum | CBS 516.95 | Polygonum sachalinense | Netherlands | A. Aptroot | JQ889276 | JQ889292 |

| Dinemasporium pseudoindicum | CBS 127402; RMF 8631 | A1 horizon soil of tallgrass prairie | USA:Kansas | M. Christensen | JQ889277 | JQ889293 |

| Dinemasporium pseudostrigosum | CBS 717.85 | Triticum aestivum | Germany | P. Reinecke | JQ889278 | JQ889294 |

| CBS 825.91; INIFAT C91/88-1 | Stigmaphyllon sagraeanum | Cuba | R.F. Castañeda | JQ889279 | JQ889295 | |

| Dinemasporium strigosum | CBS 520.78 | Hay | Netherlands | M. Nieuwstad | JQ889282 | JQ889298 |

| CBS 828.84 | Leaf spot on Secale cereale | Germany | M. Hossfeld | JQ889283 | JQ889299 | |

| CPC 18898 | Phragmites australis | Netherlands | W. Quaedvlieg | JQ889284 | JQ889300 | |

| CPC 18957 | Malus | USA:Illinois | J. Batzer | JQ889285 | – | |

| CPC 19796 | Wildenovia incurvata | South Africa | A. Wood | JQ889286 | – | |

| Pseudolachnea fraxini | CBS 113701; UPSC 1833 | Fraxinus excelsior | Sweden | K. & L. Holm | JQ889287 | JQ889301 |

1 ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA; CBS: CBS Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CPC: Culture collection of P.W. Crous, housed at CBS; INIFAT: Alexander Humboldt Institute for Basic Research in Tropical Agriculture, Ciudad de La Habana, Cuba; RMF: Martha Christensen Soil Fungus Collection; UPSC: Uppsala University Culture Collection of Fungi, Botanical Museum University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden.

2 ITS: Internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 together with 5.8S nrDNA; LSU: partial 28S nrDNA.

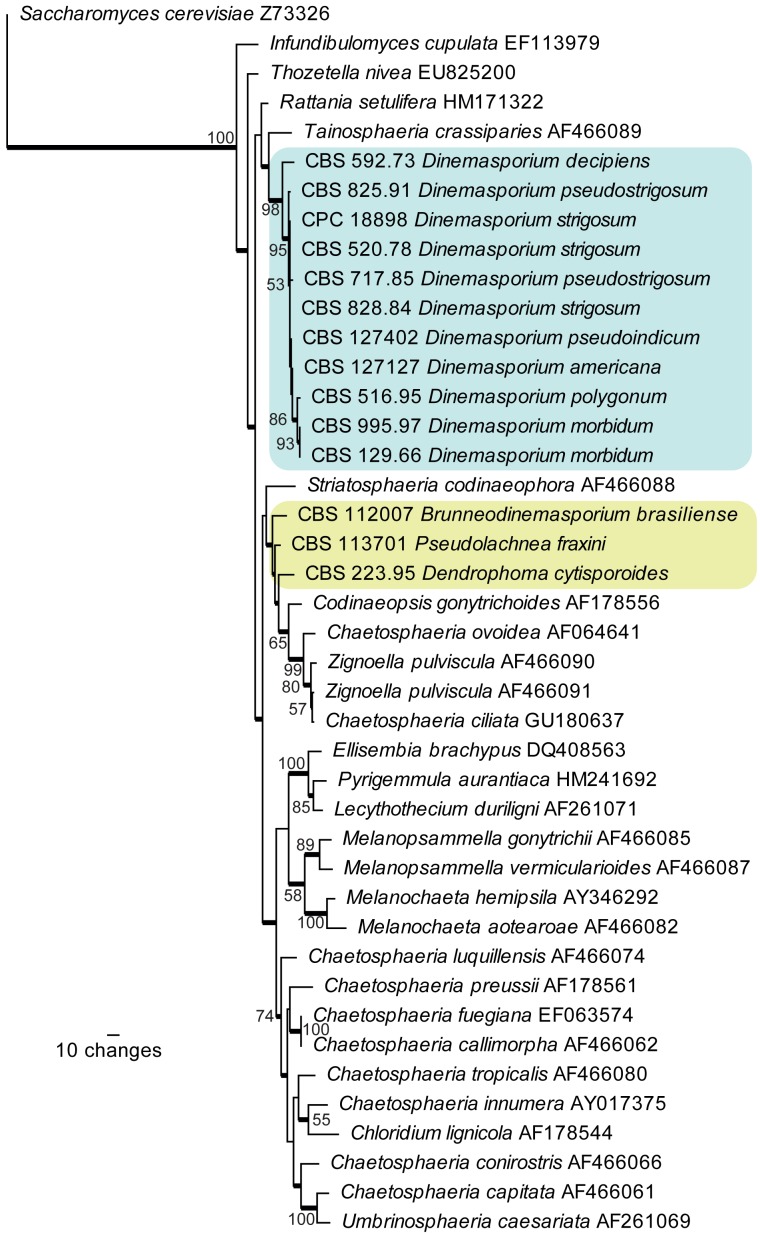

Fig. 1.

The first of 142 equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search with 100 random taxon additions of the LSU sequence alignment. The scale bar shows 10 changes, and bootstrap support values from 1 000 replicates are shown at the nodes. The species treated in this study are located in the coloured blocks. Branches present in the strict consensus tree are thickened and the tree was rooted to a sequence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (GenBank accession Z73326).

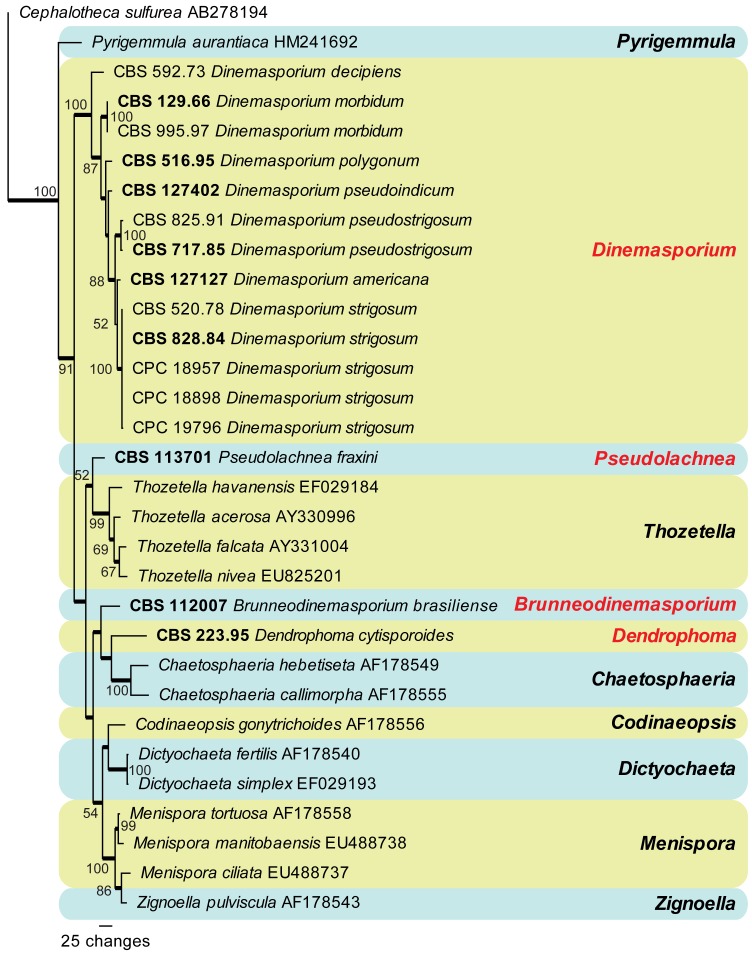

Fig. 2.

The first of three equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search with 100 random taxon additions of the ITS sequence alignment. The scale bar shows 25 changes, and bootstrap support values from 1 000 replicates are shown at the nodes. Genera are indicated in the coloured blocks and the names of genera treated in this study are written in red. Ex-type strains are printed in bold. Branches present in the strict consensus tree are thickened and the tree was rooted to a sequence of Cephalotheca sulfurea (GenBank accession AB278194).

Taxonomy

Brunneodinemasporium Crous & R.F. Castañeda, gen. nov. — MycoBank MB800158

Type species. Brunneodinemasporium brasiliense Crous.

Etymology. Similar to Dinemasporium, but conidiogenous cells and conidia brown in colour.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, setose; basal stroma of textura angularis. Setae abundant, brown to black, simple, septate, subulate to cylindrical, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, multi-septate, arising randomly throughout basal stroma. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma in a dense layer, brown, septate, unbranched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth. Conidiogenous cells integrated, determinate, phialidic with conspicuous periclinal thickening at an attenuated apex, brown, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform. Conidia hyaline to pale brown, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, fusiform, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, with a single, cellular, unbranched, flexuous, with tubular appendage at each end, separated by a septum; basal appendage excentric.

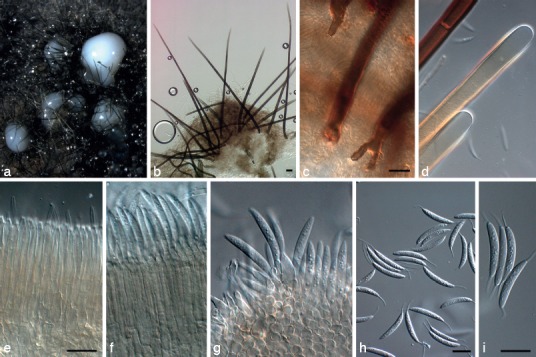

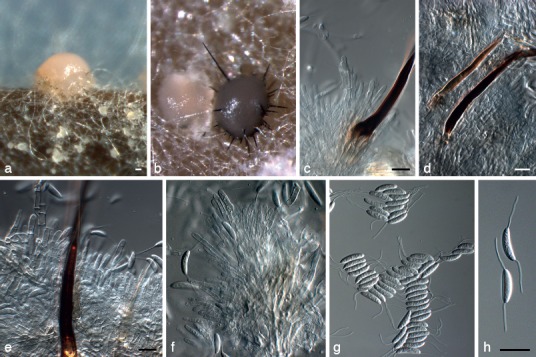

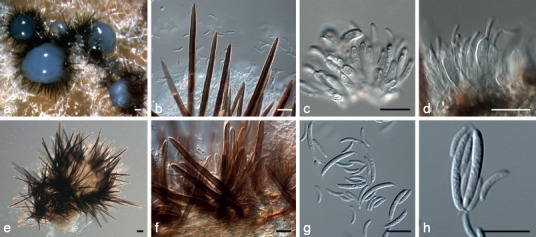

Brunneodinemasporium brasiliense Crous & R.F. Castañeda, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800159; Fig. 3

Fig. 3.

Brunneodinemasporium brasiliense (CBS 112007). a, b. Acervular conidiomata with setae; c. bases of setae; d. obtuse apices of setae; e, f. tightly aggregated layer of conidiogenous cells; g. squash of conidiogenous cells giving rise to conidia; h, i. conidia. — Scale bars: b = 20 μm, all others = 10 μm; c applies to d; e applies to f, g.

Etymology. Named after the country from where this fungus was collected, Brazil.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, up to 600 μm diam, setose with a central buff conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis. Setae abundant, brown to black, simple, septate, subulate to cylindrical, with obtuse apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, multi-septate, 200–1300 μm long, 12–15 μm diam at base, 5–10 μm diam at obtuse apex, arising from basal stroma. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma in a dense layer, brown, 4–6-septate, unbranched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, 40–70 × 3–4 μm. Conidiogenous cells integrated, determinate, phialidic with clearly visible periclinal thickening at apex 1.5–2 μm diam, brown, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform, 10–16 × 3–4 μm. Conidia hyaline to pale brown, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, fusiform, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (17−)18–19(−20) × (2−)2.5–3 μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end, 5–7 μm long, apparently separated by a septum; basal appendage excentric.

Culture characteristics — Colonies flat, spreading, with sparse to moderate aerial mycelium. On MEA smoke grey (surface), with even, lobate margins, surrounded by a zone of diffuse, red pigment; reverse olivaceous grey in centre, outer region red due to diffuse pigment; on OA iron grey with even, lobate margin; on PDA surface isabelline, in outer region smoke grey, in reverse grey olivaceous.

Specimen examined. Brazil, Corcorvado, on decaying leaf, 12 Oct. 2002, R.F. Castañeda-Ruiz (holotype CBS H-20948, culture ex-type CBS 112007 = INIFAT CO2/51).

Notes — Brunneodinemasporium has randomly distributed setae throughout the basal stroma, which differs from Dinemasporium, which has a densely aggregated layer of brown conidiogenous cells with prominent periclinal thickening and apical taper, and conidia that appear pale brown, and have setae that separate from the conidia by a septum (though the latter is not clear under the light microscope, but differs from Dinemasporium s.str.).

Dendrophoma Sacc., Michelia 2: 4. 1880.

= Amphitiarospora Agnihothr., Sydowia 16: 75. 1962 (1963).

Type species. Dendrophoma cytosporoides Sacc.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered to gregarious, superficial, stipitate, globose and closed, becoming cupulate, unilocular, dark brown to black; basal excipulum brown, of dense textura intricata. Setae arising from the outer elements of excipulum, or restricted to base of conidioma, sparse, subulate to subcylindrical, apex blunt to acutely rounded, straight to curved, transversely septate, dark brown, thick-walled, smooth. Conidiophores arising from conidiomatal cavity, septate, branched, hyaline. Conidiogenous cells discrete, or integrated, terminal and lateral, lageniform to subcylindrical, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth. Conidia naviculate to botuliform, aseptate, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, with an unbranched cellular appendage at each end.

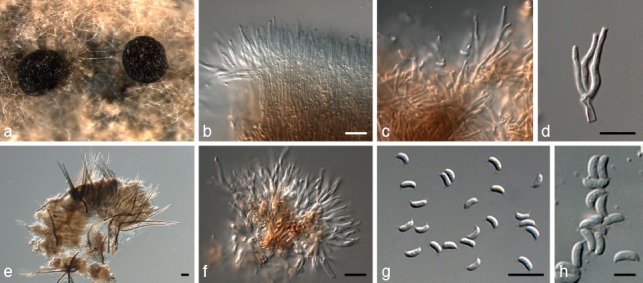

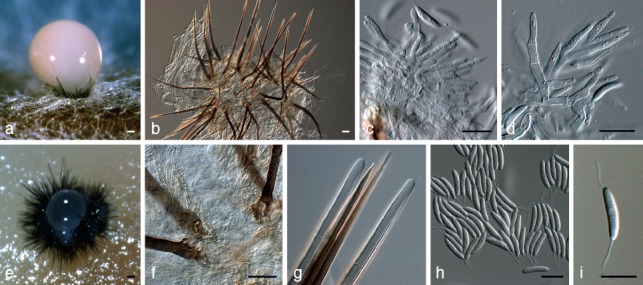

Dendrophoma cytosporoides Sacc., Michelia 2: 4. 1880; Fig. 4

Fig. 4.

Dendrophoma cytosporoides (CBS 223.95). a. Stalked acervuli forming in culture; b–d, f. conidiogenous cells; e. setae; g, h. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except e = 20 μm.

Basionym. Phoma cytosporoides Sacc. (as ‘cytisporoides’), Michelia 1, 5: 522. 1879.

≡ Dinemasporium cytosporoides (Sacc.) B. Sutton, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 48: 613. 1965.

= Amphitiarospora neottiosporoides Agnihothr., Sydowia 16: 75. 1962 (1963).

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered to gregarious, superficial, stipitate, at first globose and closed, then opening to become cupulate, up to 300 μm diam, unilocular, dark brown to black; basal excipulum brown, of dense textura intricata. Setae arising from the outer elements of excipulum, or restricted to base of conidioma, sparse, subulate to subcylindrical, apex blunt to acutely rounded, straight to curved, 2–8-septate, dark brown, thick-walled, smooth, 100–300 × 4–6 μm, apex 1–1.5 μm wide. Conidiophores arising from conidiomatal cavity, septate, branched, hyaline, up to 40 μm long. Conidiogenous cells discrete or integrated, terminal and lateral, lageniform to subcylindrical, frequently in terminal whorls, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, 6–15 × 1.5 μm. Conidia naviculate to botuliform, aseptate, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, (3.5−)4–5(−6) × (1−)1.5 μm, with an unbranched appendage at each end, 0.5–1 μm long.

Culture characteristics — Colonies flat, spreading, with sparse aerial mycelium and even, lobate margins. On OA surface grey olivaceous, reverse olivaceous grey; on PDA surface brick to cinnamon, reverse dark brick.

Specimens examined. France, Rouen, L’ Abbee Letendre, on Ulmus sp., designated as lectotype of Phoma cytosporoides by Sutton (1965), IMI 111879 ex Herb. PAD. – Netherlands, Utrecht, Soest, near hospital, on Rhododendron, coll. A. Aptroot, isol. G. Verkley, 11 Nov. 1994 (epitype designated here CBS H-12004, culture ex-epitype CBS 223.95).

Notes — The characteristic features that separate Dendrophoma from Dinemasporium are conidiomata that are superficial and stipitate, becoming cupulate. The conidiogenous cells of Dendrophoma form a dense layer that gives rise to conidia with short, tubular exogenous appendages at each end, also differing from Dinemasporium s.str.

Based on an examination of the holotype specimen, Sutton (1977, 1980) regarded Amphitiarospora as synonymous with Dinemasporium. The original description (conidia 4–5 × 1.5–2 μm, setae 1–2 μm; Agnihothrudu 1962), indicated that A. neottiosporoides is synonymous with D. cytosporoides.

Dinemasporium Lév., Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 3, 5: 274. 1846.

= Dinemasporium (Lév.) subg. Stauronema Sacc., Syll. Fung. 3: 686. 1884.

≡ Stauronema (Sacc.) Syd., P. Syd. & E.J. Butler, Ann. Mycol. 14: 217. 1916.

= Pycnidiochaeta Sousa da Câmara, Agron. Lusit. 12: 109. 1950.

Type species. Dinemasporium strigosum (Pers.: Fr.) Sacc.

Conidiomata stromatic, cupulate, often discoid, superficial (also on SNA in culture), unilocular, setose, black, with basal stroma of textura angularis. Setae arise from the basal stroma and/or from excipular margin, unbranched, subulate to cylindrical, straight or curved, brown to dark brown, smooth or verruculose, with obtuse to acute apices. Conidiophores lining the inner cavity, mostly branched, septate, hyaline (at times brown at base), smooth, invested in mucus. Conidiogenous cells discrete or integrated, lageniform, subcylindrical or cylindrical, hyaline, smooth, with visible periclinal thickening. Conidia fusiform, naviculate or allantoid, aseptate, hyaline to pale brown, smooth, with a single, unbranched, filiform, cellular appendage at each end (not separated from body via septa); lateral appendages present or absent.

Dinemasporium americana Crous & Tuthill, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800160; Fig. 5

Fig. 5.

Dinemasporium americana (CBS 127127). a, b. Acervular conidiomata forming in culture; c–e. setae and conidiogenous cells; f. conidiogenous cells; g, h. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm; e applies to f.

Etymology. Named after its country of origin, Unites States of America.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, up to 350 μm diam, setose with a central buff to rosy buff conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis, layer 20–30 μm thick. Setae brown to black, simple, septate, subulate with acute apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, up to 7-septate, 50–200 × 4–10 μm, 1–1.5 μm wide at acute apex, arising from basal stroma or lateral from excipulum. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma, prominently septate (−8), branched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, base pale brown, apex hyaline, up to 70 μm long. Conidiogenous cells determinate, phialidic with periclinal thickening, hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical, 7–10 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, naviculate to fusiform or ellipsoid, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (9−)12–13(−16) × (2.5−)3 μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end, (11−)12–14(−16) μm; basal appendage excentric.

Culture characteristics — Colonies spreading, erumpent, with moderate aerial mycelium. On MEA buff (surface), reverse cinnamon; on OA and PDA buff (surface and reverse).

Specimen examined. USA, Iowa, Cherokee County, Steele Prairie, A1 horizon soil, 1985, D.E. Tuthill, T93N R40W S16 (holotype CBS H-20949, dried culture of RMF 7507 = CBS 127127).

Notes — Isolate RMF 7507 was formerly treated as D. strigosum, but is specifically distinct. Although the conidiomata produced are similar in general morphology to those of D. strigosum, they differ by having shorter setae, larger conidia, longer appendages (setae 60–400 μm long, conidia (9−)10–12(−13) μm long, appendages 6–9 μm long in D. strigosum).

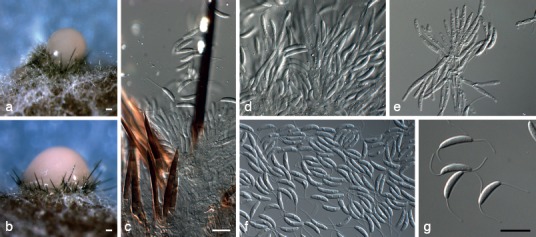

Dinemasporium morbidum Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800161; Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

Dinemasporium morbidum (CBS 129.66). a, b. Acervular conidiomata forming in culture; c. setae. d, e. conidiogenous cells; f, g. bases and apices of setae; h, i. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except a = 20 μm.

Etymology. Name reflects on the unpleasant substrata from which the fungus was isolated.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, up to 250 μm diam, setose with a central buff conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis, layer 20–30 μm thick. Setae brown to black, simple, septate, subulate with acute apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, up to 9-septate, 50–330 × 5–10 μm, 1–1.5 μm wide at acute apex, arising from basal stroma or lateral from excipulum. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma, hyaline, septate, sparingly branched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, 30–40 μm long. Conidiogenous cells determinate, phialidic with periclinal thickening, hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform, 8–13 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, naviculate to fusiform or ellipsoid, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (10−)12–14(−15) × (2.5−)3 μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end, (6−)7–10(−12) μm; basal appendage excentric.

Culture characteristics — Colonies spreading, erumpent, with moderate aerial mycelium. On MEA, OA and PDA buff (surface), reverse buff with patches of cinnamon; sporulation rosy buff.

Specimens examined. Netherlands, from human sputum, 19 Nov. 1965, N.G.M. Orie and A. Kikstra, No. A 29/9 (holotype CBS H-12014, culture ex-type 129.66). – New Zealand, South Island, Hobson’s Nature trail near Highway 13, Arthur’s Pass, on hare dung, Mar. 1995, D.P. Mahoney, CBS 995.97 = ATCC 200690.

Notes — Dinemasporium morbidum has longer conidia and appendages than D. strigosum, which has conidia (9−)10–12 (−13) μm long, with appendages 6–9 μm long.

Dinemasporium polygonum Crous & Verkley, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800162; Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Dinemasporium polygonum (CBS 516.95). a, b. Acervular conidiomata forming in culture; c. setae; d, e. conidiogenous cells; f, g. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except a, b = 20 μm.

Etymology. Named after the host genus from which it was isolated, Polygonum.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, up to 250 μm diam, setose with a central buff to rosy buff conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis, layer 20–30 μm thick. Setae brown to black, simple, septate, subulate with acute apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, up to 9-septate, 100–300 × 5–8 μm, 1–1.5 μm wide at acute apex, arising from basal stroma or lateral from excipulum. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma, hyaline, septate, sparingly branched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, 30–60 μm long. Conidiogenous cells determinate, phialidic with periclinal thickening, hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform, 7–16 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, naviculate to fusiform or ellipsoid, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (9−)10–12(−13) × (2−)2.5(−3) μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end, (9−)10–12(−13) μm; basal appendage excentric.

Culture characteristics — Colonies spreading, erumpent, with moderate aerial mycelium. On MEA, OA and PDA buff (surface and reverse).

Specimen examined. Netherlands, Soest, de Stompert, on Polygonum sachalinense, 22 Feb. 1995, coll. A. Aptroot, isol. G.J.M. Verkley (holotype CBS H-20950, culture ex-type CBS 516.95).

Notes — Dinemasporium polygonum has conidia with longer appendages than D. strigosum though shorter than in D. americanum (6–9 μm long in D. strigosum, 11–16 μm in D. americanum).

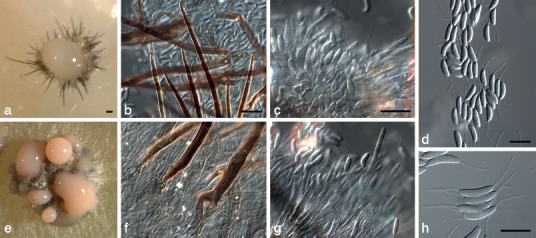

Dinemasporium pseudoindicum Crous & M. Chr., sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800163; Fig. 8

Fig. 8.

Dinemasporium pseudoindicum (CBS 127402). a, b. Acervular conidiomata forming in culture; c, d. setae; e. conidiogenous cells; f–h. conidia, showing apical, lateral and basal appendages. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except a = 20 μm, applies also to b.

Etymology. Named after its morphological similarity to Stauronema indicum.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose to oval, irregular in outline, 300–400 μm diam, setose with a central cream conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis, layer 20–30 μm thick. Setae brown, simple, septate, subulate with acute to obtuse apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, up to 4-septate, 100–400 × 4–8 μm, 1–1.5 μm wide at acute apex, or 4 μm when obtuse at apex, arising from basal stroma or lateral from excipulum. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma, hyaline, but pigmented in basal part, septate, sparingly branched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, 20–40 μm long, invested in mucus. Conidiogenous cells determinate, phialidic with periclinal thickening, rarely indeterminate and proliferating percurrently at apex, hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform, 5–15 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, naviculate to fusiform or ellipsoid, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (9−)10–12(−13) × (3−)3.5(−4) μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end; basal appendage excentric; apical and basal appendages 9–22 μm long; lateral appendages 2, inserted 4–6 μm below apex, 10–17 μm long.

Culture characteristics — Colonies spreading, erumpent, with moderate aerial mycelium on OA, but with sparse aerial mycelium on PDA and MEA. On MEA rosy buff (surface), reverse cinnamon with patches of buff; on OA buff; on PDA grey olivaceous in centre, buff in outer region, and buff in reverse.

Specimen examined. USA, Kansas, near Manhattan, Konza Prairie Research Natural Area, long-term ecological research site, A1 horizon soil, tallgrass prairie, June 1987, M. Christensen (holotype CBS H-20951, culture ex-type RMF 8631 = CBS 127402).

Notes — Morphologically similar to Stauronema indicum, but distinct in that it has larger conidia and appendages of different length, and at different positions in relation to the conidial apex (conidia 7–13 × 2–3 μm, terminal appendages 6.5–17 μm, lateral appendages 8–20 μm long, but 3–4 μm below apex; Nag Raj 1993).

Dinemasporium pseudostrigosum Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800164; Fig. 9

Fig. 9.

Dinemasporium pseudostrigosum (CBS 717.85). a, b. Acervular conidiomata forming in culture; c, d. setae; e, f. conidiogenous cells; g, h. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except a = 20 μm, applies also to b.

Etymology. Named after its morphological similarity to D. strigosum.

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, up to 250 μm diam, setose with a central buff to rosy buff conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis, layer 20–30 μm thick. Setae brown to black, simple, septate, subulate with acute apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, up to 7-septate, 100–250 × 5–8 μm, 1–1.5 μm wide at acute apex, arising from basal stroma or lateral from excipulum. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma, hyaline, septate, sparingly branched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, 30–40 μm long. Conidiogenous cells determinate, phialidic with periclinal thickening, hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform, 10–15 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, naviculate to fusiform or ellipsoid, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (10−)12–13(−14) × (2.5−)3 μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end, (11−)13–15(−17) μm; basal appendage excentric.

Culture characteristics — Colonies spreading, erumpent, with moderate aerial mycelium. On MEA buff (surface), reverse cinnamon in middle, buff in outer region; on OA buff with profuse sporulation (peach in colour); on PDA dirty white to buff (surface and reverse).

Specimens examined. Cuba, Granma, on Stigmaphyllon sagraeanum, 14 Mar 1991, R.F. Castañeda, INIFAT C91/88-1 = CBS 825.91. – Germany, Monheim, on Triticum aestivum, Sept. 1985, P. Reinecke, (holotype CBS H-12018, culture ex-type CBS 717.85).

Notes — Morphologically D. pseudostrigosum is similar to D. strigosum, but distinct in that it has larger conidia, and longer appendages.

Dinemasporium strigosum (Pers.: Fr.) Sacc., Michelia 2: 281. 1881; Fig. 10

Fig. 10.

Dinemasporium strigosum (CBS 828.84). a–c. Acervular conidiomata forming in vivo; d, e. setae; f, g. conidiogenous cells; h, i. conidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except a = 20 μm, applies also to b, c; d applies to e; f applies to g.

Basionym. Peziza strigosa Pers.: Fr., Syst. Mycol. 2: 103. 1823.

≡ Polynema strigosa (Pers.: Fr.) Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 23–24: 367. 1870.

= Vermicularia graminum Lib., Pl. Crypt. Arduenna, fasc. (Liège) 4: no. 348. 1837.

≡ Excipula graminum (Lib.) Corda, Icon. Fungorum (Prague) 3: 29. 1839.

≡ Dinemasporium graminum (Lib.) Lév., Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot., ser. 3, 5: 274. 1846.

= Excipula betulae Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 15: 64. 1860.

≡ Polynema betulae (Fuckel) Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 23–24: 367. 1870.

≡ Dinemasporium betulae (Fuckel) Sacc., Syll. Fung. 3: 686. 1884.

= Dinemasporium longisetum Syd., Ann. Mycol. 34, 4/5: 400. 1936.

= Ellisiellina biciliata Sousa da Câmara, Agron. Lusit. 11: 72. 1949.

= Pycnidiochaeta biciliata Sousa da Câmara, Agron. Lusit. 12, 1: 109. 1950.

For additional synonyms see Sutton (1980) and Nag Raj (1993).

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered or aggregated, superficial, dark brown to black, cupulate, unilocular, globose, up to 250 μm diam, setose with a central buff to rosy buff conidial mass on PNA; basal stroma of textura angularis, layer 20–30 μm thick. Setae brown to black, simple, septate, subulate with acute apex, unbranched, smooth, thick-walled, up to 9-septate, 60–400 × 7–10 μm, 1–1.5 μm wide at acute apex, arising from basal stroma or lateral from excipulum. Conidiophores lining the basal stroma, hyaline, septate, sparingly branched, cylindrical, thin-walled, smooth, 30–40 μm long. Conidiogenous cells determinate, phialidic with periclinal thickening, hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical to lageniform, 12–15 × 2–2.5 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, thin-walled, smooth, naviculate to fusiform or ellipsoid, gently curved or straight, apex obtuse to subobtusely rounded, base truncate, eguttulate or guttulate, (9−)10–12(−13) × (2−)2.5(−3) μm, with a single, unbranched, flexuous, tubular appendage at each end, (6−)7–8(−9) μm; basal appendage excentric.

Culture characteristics — Colonies spreading, erumpent, with moderate aerial mycelium. On MEA buff (surface), rosy buff (reverse); on OA buff with profuse sporulation (peach in colour); on PDA buff (surface and reverse).

Specimens examined. Belgium, Ardenne, on dried grass blades, Libert, Pl. Crypt. Arduennae, 1837, syntype of D. graminum, K(M) 175982. – Germany, Baden-Werttemberg, Eberbach, on rotton wood of Betula sp., Fuckle’s Fungi Rhenani exs 205, syntype of D. betulae, K(M) 175979; Brandenburg, Freienwalde near Oder, on leaves of Populus tremula, H. Sydow Mycotheca Germanica exs 2978, 30 Sept. 1934, syntype of D. longisetum, K(M) 175980; Monheim, on Secale cereale, May 1984, M. Hossfeld, (epitype designated here CBS H-20952, culture ex-epitype CBS 828.84). – Netherlands, Beemster, from hay, M. Nieuwstad, Oct. 1978, specimen CBS H-12008, culture CBS 520.78; Wageningen, on Phragmites australis, 15 Nov. 2010, W. Quaedvlieg, CPC 18898, 18899. – Portugal, Ribatejo, on leaves of Dactylis hispanica, Garcia Cabral 307, 30 Aug. 1950, holotype of Ellisiellina biciliata LISE 41853; Serra do Geres, on culms of Agrostis castellana, 9 July 1948, M.R. de J. Dias, holotype of Pycnidiochaeta biciliata, LISE 50037. – South Africa, Western Cape Province, Bracken Nature Reserve, on Wildenovia incurvata, 18 Aug. 2011, A. Wood, CPC 19796, 19797. – Sweden, on grass blades, E. Fries, Scler. Suecicae exs 136, isotype of Peziza strigosa K(M) 175981.– USA: Illinois, Rockford, from Malus, J. Batzer, Sept. 2000, specimen CBS H-19787, culture CBS 18957.

Notes — Dinemasporium strigosum and its purported synonyms have been treated by several authors (Webster 1955, Sutton 1980, Nag Raj 1993, Yamaguchi et al. 2005, Duan et al. 2007). The synonyms proposed by Sutton (1980) and Nag Raj (1993) were accepted based on the examination of the type material cited above.

Although D. strigosum was linked to a sexual state described as Phomatospora dinemasporium (Webster 1955), the generic placement was questioned by Rappaz (1992), as other species of Phomatospora have been linked to hyphomycetes with Fusarium-like conidia. No sexual states were encountered or induced in the present study.

Pseudolachnea Ranoj., Ann. Mycol. 8: 593. 1910 [non Pseudolachnea Velen. 1934].

= Dinemasporiella Bubák & Kabát, Hedwigia 52: 358. 1912; non Dinemasporiella Speg., Annales Mus. Nac. Buenos Aires 20: 366. 1910 (nom. dub.).

≡ Dinemasporiopsis Bubák & Kabát, nom. nov., apud Died., Krypt.-Fl. Mark Brandenburg 9: 750. 1915.

= Chaetopatella Hino & Katum., J. Jap. Bot. 33: 238. 1958.

Type species. Pseudolachnea hispidula (Schrad.) B. Sutton (= P. bubakii Ranoj.).

Conidiomata stromatic, scattered to gregarious, cupulate, superficial, unilocular, setose, dark brown to black; basal stroma of textura angularis. Setae divergent, subulate with blunt or acute apices, unbranched, septate, thick-walled, smooth, dark brown. Conidiophores arising from the uppermost cells of the basal stroma and the inner cells of the excipulum, branched, septate, brown at base, hyaline in upper part, smooth, invested in a thin layer of mucus. Conidiogenous cells discrete, phialidic with periclinal thickening, cylindrical, hyaline, smooth. Macroconidia fusiform with obtuse ends, 1-septate, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, bearing an unbranched, short, cellular, filiform appendage at each end; appendages not delimited by septa, basal appendage excentric. Microconidia intermixed with macroconidia in same conidioma, fusiform, curved with rounded ends, aseptate, smooth, guttulate, lacking appendages.

Pseudolachnea fraxini Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB800165; Fig. 11

Fig. 11.

Pseudolachnea fraxini (CBS 113701). a, b. Acervular conidiomata forming in culture; c, d. setae; e, f. conidiogenous cells; g. h. macro- and microconidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm, except a = 20 μm, applies also to b.

Etymology. Named after the host from which it was collected, Fraxinus.

Conidiomata on OA stromatic, scattered to gregarious, cupulate, superficial, unilocular, setose, dark brown to black, up to 300 μm diam; basal stroma of textura angularis. Setae divergent, subulate with blunt or acute apices, unbranched, septate only at the base, thick-walled, smooth, dark brown, 40–170 × 4–7 μm. Conidiophores arising from the uppermost cells of the basal stroma and the inner cells of the excipulum, sparsely branched and septate at the base, up to 20 μm long, brown at base, hyaline in upper part, smooth, invested in a thin layer of mucus. Conidiogenous cells discrete, phialidic with periclinal thickening, cylindrical, hyaline, smooth, 6–12 × 2–3 μm. Macroconidia fusiform with obtuse ends, 1-septate, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, (12−)15–16(−18) × 2(−2.5) μm, bearing an unbranched, short, cellular, filiform appendage at each end, 1.5–2 μm long; appendages not delimited by septa, basal appendage excentric. Microconidia common, intermixed with macroconidia in same conidioma, fusiform, curved with rounded ends, aseptate, smooth, guttulate, (6−)7–9 × (1−)1.5 μm, lacking appendages.

Culture characteristics — Colonies flat, spreading, with sparse aerial mycelium and even, lobate margins. On MEA dirty white (surface), reverse cinnamon; on OA surface honey to isabelline, reverse honey; on PDA dirty white (surface and reverse).

Specimen examined. Sweden, Uppland, Dalby par., Jerusalem, on Fraxinus excelsior, coll. K. & L. Holm, isol. O. Constantinescu, 31 Mar. 1986 (holotype CBS H-20953, culture ex-type CBS 113701).

Notes — The ex-type culture of P. fraxini (CBS 113701) was originally identified as P. hispidula. Pseudolachnea fraxini differs from P. hispidula by having much smaller conidiomata, shorter setae, larger conidia (conidiomata 600–1200 μm diam, setae 80–220 μm long, conidia 11–14 μm long in P. hispidula; Nag Raj 1993), and forms primarily microconidia in culture, an aspect not yet observed in P. hispidula.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the genus Dinemasporium with the aim of evaluating the importance of conidial appendages as taxonomic characters at generic level among coelomycetous taxa. Dinemasporium has several acknowledged synonyms, including Dendrophoma, Pycnidiochaeta, and Amphitiarospora. Species with septate conidia were allocated to other genera (Pseudolachnea, Pseudolachnella), while those with apical, basal and lateral setae, were placed in Stauronema (Sutton 1980, Nag Raj 1993).

Based on these findings, a new genus, Brunneodinemasporium is introduced to accommodate a Dinemasporium-like species with tightly aggregated brown conidiogenous cells, and pale brown conidia. Furthermore, the genus Dendrophoma (= Amphitiarospora) is reinstated as distinct from Dinemasporium. Dendrophoma (which is based on D. cytosporoides) has superficial, stipitate to cupulate conidiomata, and small conidia with two polar, tubular, exogenous appendages, which separates it from Dinemasporium. The genus Stauronema is reduced to synonymy under Dinemasporium, and lateral conidial appendages rejected as a useful single character for generic separation. The genus Pseudolachnea (1-septate conidia) is supported as distinct from Dinemasporium (aseptate conidia), though no cultures were available to determine if Pseudolachnella (multi-septate conidia) needs to be reduced to synonymy with Pseudolachnea (Sutton 1980), or retained as separate genus (Nag Raj 1993).

The genus Dinemasporium is a phylogenetically well-defined genus in the Chaetosphaeriaceae. Dinemasporium is circumscribed based on D. strigosum, which is also epitypified in this study. Five novel species are described from a collection of cultures formerly treated as D. strigosum. Taxa in this complex appear to differ by a combination of morphological features of the setae, conidia and conidial appendages.

Other than revising taxa in the Dinemasporium complex, a major aim of the present study was to determine the relevance of appendages as delimiting feature at generic level in coelomycetous fungi. Conidial appendages have been used extensively to support the separation of species (e.g. Coniella, Phyllosticta, van Niekerk et al. 2004, Glienke et al. 2011), but have also been used to separate genera of coelomycetous fungi (e.g. Discosia, Pestalotiopsis, Seimatosporium, Tiarosporella, Crous et al. 2006, Barber et al. 2011, Maharachchikumbura et al. 2011, Tanaka et al. 2011).

Results from the present study revealed that conidial appendages in coelomycetes are not informative as generic characters when looked at in isolation, as recently reported for the Seimatosporium complex (Barber et al. 2011). Although appendage morphology appeared to be highly informative at the species level (mucilaginous or cellular, endo- or exogenous, simple or branched, as well as their position on the conidium body), they appeared to be less informative when used in isolation as generic feature. We can conclude that genera separated chiefly on the basis of appendage morphology, e.g. Dinemasporium and Stauronema, or Seimatosporium and Vermisporium (Barber et al. 2011), represent only two genera, namely Dinemasporium and Seimatosporium. This finding could also have implications for other more commonly encountered genera, e.g. Pestalotiopsis and Pestalotia, which are also separated solely on the basis of apical appendage morphology. Pestalotia (1839) predates Pestalotiopsis (1949), which will have serious implications for names in Pestalotiopsis, which is presently the more commonly used genus.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical staff, Arien van Iperen (cultures), Marjan Vermaas (photo plates), and Mieke Starink-Willemse (DNA isolation, amplification and sequencing) for their invaluable assistance.

REFERENCES

- Agnihothrudu V. 1962. Notes on fungi from North-east India XIV – A new genus of Discellaceae from Assam. Sydowia 16: 73–76 [Google Scholar]

- Barber PA, Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Pascoe IG, Keane P. 2011. Reassessing Vermisporium (Amphisphaeriaceae), a genus of foliar pathogens of eucalypts. Persoonia 27: 90–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Gams W, Stalpers JA, Robert V, Stegehuis G. 2004. MycoBank: an online initiative to launch mycology into the 21st century. Studies in Mycology 50: 19–22 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Schoch CL, Hyde KD, Wood AR, Gueidan C, et al. 2009a. Phylogenetic lineages in the Capnodiales. Studies in Mycology 64: 17–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Slippers B, Wingfield MJ, Rheeder J, Marasas WFO, et al. 2006. Phylogenetic lineages in the Botryosphaeriaceae. Studies in Mycology 55: 235–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Verkley GJM, Groenewald JZ, Samson RA. (eds). 2009b. Fungal Biodiversity. CBS Laboratory Manual Series 1. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Park RF. 1991. Mycosphaerella nubilosa a synonym of M. molleriana. Mycological Research 95: 628–632 [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Wu W, Liu XZ. 2007. Dinemasporium (coelomycetes). Fungal Diversity 26: 205–218 [Google Scholar]

- Glienke C, Pereira OL, Stringari D, Fabris J, Kava-Cordeiro V , et al. 2011. Endophytic and pathogenic Phyllosticta species, with reference to those associated with Citrus Black Spot. Persoonia 26: 47–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Gerrits van den Ende AHG. 1998. Molecular diagnostics of clinical strains of filamentous Basidiomycetes. Mycoses 41: 183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharachchikumbura SSN, Guo LD, Chukeatirote E, Bahkali AH, Hyde KD. 2011. Pestalotiopsis – morphology, phylogeny, biochemistry and diversity. Fungal Diversity 50: 167–187 [Google Scholar]

- Nag Raj TR. 1993. Coelomycetous anamorphs with appendage-bearing conidia. Mycologue Publications, Waterloo, Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Niekerk JM van, Groenewald JZ, Verkley GJM, Fourie PH, Wingfield MJ, Crous PW. 2004. Systematic reappraisal of Coniella and Pilidiella, with specific reference to species occurring on Eucalyptus and Vitis in South Africa. Mycological Research 108: 283–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaz F. 1992. Phomatospora berkeleyi, P. arenaria and their Sporothrix anamorphs. Mycotaxon 45: 323–330 [Google Scholar]

- Rayner RW. 1970. A mycological colour chart. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew [Google Scholar]

- Saccardo PA. 1884. Sylloge fungorum 3: 1–860 [Google Scholar]

- Smith H, Wingfield MJ, Crous PW, Coutinho TA. 1996. Sphaeropsis sapinea and Botryosphaeria dothidea endophytic in Pinus spp. and Eucalyptus spp. in South Africa. South African Journal of Botany 62: 86–88 [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC. 1965. Typification of Dendrophoma and a reassessment of D. obscurans. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 48: 611–616 [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC. 1977. Coelomycetes VI. Nomenclature of generic names proposed for Coelomycetes. Mycological Papers 141: 1–253 [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC. 1980. The Coelomycetes: Fungi imperfecti with pycnidia, acervuli, and stromata. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surrey [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC, Sellar PW. 1966. Toxosporiopsis n. gen., an unusual member of melanconiales. Canadian Journal of Botany 44: 1505–1513 [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Endo M, Hirayama K, Okane I, Hosoya T, Sato T. 2011. Phylogeny of Discosia and Seimatosporium, and introduction of Adisciso and Immersidiscosia genera nova. Persoonia 26: 85–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M. 1990. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172: 4238–4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J. 1955. Graminicolous pyrenomycetes V. Conidial state of Leptosphaeria michotii, L. microspica, Pleospora vagans and the perfect states of Dinemasporium graminum. Transitions of the British Mycological Society 38: 347–365 [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee J, Taylor SB. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ. (eds), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications: 315–322. Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA [Google Scholar]

- Wikee S, Udayanga D, Crous PW, Chukeatirote E, McKenzie EHC , et al. 2011. Phyllosticta – an overview of current status of species recognition. Fungal Diversity 51: 43–61 [Google Scholar]

- Wulandari NF, To-anun C, Hyde KD, Duong LM, Gruyter J de , et al. 2009. Phyllosticta citriasiana sp. nov., the cause of Citrus tan spot of Citrus maxima in Asia. Fungal Diversity 34: 23–39 [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Masuma R, Tomoda H, Omura S. 2005. A new species of Dinemasporium from sugar cane on Irabujima island, Japan. Mycoscience 46: 367–369 [Google Scholar]