Abstract

Alcohol use disorders are associated with increased lung infections and exacerbations of chronic lung diseases. Whereas the effects of cigarette smoke are well recognized, the interplay of smoke and alcohol in modulating lung diseases is not clear. Because innate lung defense is mechanically maintained by airway cilia action and protein kinase C (PKC)-activating agents slow ciliary beat frequency (CBF), we hypothesized that the combination of smoke and alcohol would decrease CBF in a PKC-dependent manner. Primary ciliated bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to 5% cigarette smoke extract plus100 mmol/L ethanol for up to 24 hours and assayed for CBF and PKCε. Smoke and alcohol co-exposure activated PKCε by 1 hour and decreased both CBF and total number of beating cilia by 6 hours. A specific activator of PKCε, DCP-LA, slowed CBF after maximal PKCε activation. Interestingly, activation of PKCε by smoke and alcohol was only observed in ciliated cells, not basal bronchial epithelium. In precision-cut mouse lung slices treated with smoke and alcohol, PKCε activation preceded CBF slowing. Correspondingly, increased PKCε activity and cilia slowing were only observed in mice co-exposed to smoke and alcohol, regardless of the sequence of the combination exposure. No decreases in CBF were observed in PKCε knockout mice co-exposed to smoke and alcohol. These data identify PKCε as a key regulator of cilia slowing in response to combined smoke and alcohol-induced lung injury.

Chronic inflammatory lung disease represents the third leading cause of death in the United States,1 primarily because of cigarette smoking. Although a large percentage of cigarette smokers consume alcohol, relatively few studies have examined the combination effects of cigarette smoke plus alcohol on the various functions of the lung. Understanding the interplay of these two important agents may reveal novel pathway targets that might treat or prevent adverse health consequences. Although innate lung defenses against inhalation injury are often attributed to the action of immune effector cells, earlier mechanical defenses in the lung consist of exhalation, cough, and mucociliary clearance, in which inhaled particles, toxins, and pathogens are trapped in the mucus layer that covers the airways and are propelled from the lungs via the unidirectional motion of the beating cilia.

The effect of cigarette smoke on ciliary beat frequency (CBF) is not clearly defined or well characterized. Depending on the model system, there are reports of both decreased and increased cilia beating after cigarette smoke exposure.2,3 Alcohol also has a biphasic effect on CBF: transient modest alcohol exposure rapidly stimulates ciliary beat, whereas sustained higher dose alcohol exposure leads to a desensitization of the ciliostimulatory machinery, resulting in impaired mucociliary clearance.4 Despite these advances in our understanding of individual effects of cigarette smoke or alcohol on cilia, little is known about co-exposure effects. Previously, we reported that cigarette smoke and alcohol co-exposure resulted in a significant decrease in bacterial clearance from the lung in a rodent model.5 Unique to this co-exposure was the observation that ciliary beating not only failed to stimulate in response to an otherwise routine stimulatory challenge, but also CBF actually decreased below baseline values.6 The mechanism of this active cilia-slowing response has not been defined.

Regulatory mechanisms that control decreases in cilia beating are not as well described as cilia stimulatory mechanisms. Cilia stimulation involves the second messengers, calcium, cAMP, nitric oxide, and cGMP, which have all been shown to activate target kinases (PKA, PKG) to produce an increase in ciliary beating.7 However, decreases in CBF have been associated with the action of protein kinase C (PKC). PKC-activating agents, such as phorbol esters, have been reported to slow cilia, and PKC-mediated phosphorylation of ciliary substrates also slows ciliary beating.8 Likewise, numerous agents have been reported to decrease ciliary beating such as respiratory syncytial virus,9 sodium metabisulphite,10 organic dusts from animal confinement,11 tumor necrosis factor α,12 and acetaldehyde.13 Importantly, all of these agents activate PKC in the lung. Of the various PKC isoforms, Wong et al14 first proposed that the action of calcium-independent novel isoform, PKC, was responsible for cilia slowing in response to neuropeptide Y. We previously reported that PKCε is a novel isoenzyme contained in ciliated airway epithelium.15

On the basis of those studies, we hypothesized that the combination of cigarette smoke and alcohol would slow ciliary motility in a PKC-dependent manner. To investigate this hypothesis, we examined cigarette smoke and alcohol effects on cilia beat and PKC activity with the use of in vitro models of intact ciliated primary bovine cells and isolated bovine ciliary axonemes, in culture, in situ-exposed precision-cut mouse lung slices, and in vivo smoke- and alcohol-treated normal and homozygous Prkce knockout mice. Our findings suggest that only the combination of cigarette smoke and alcohol, but not either individually, leads to a rapid slowing of CBF. This smoke and alcohol combination exposure leads to the activation of the PKC isoform ε (PKCε), which immediately precedes cilia slowing.16 This unique effect of combined cigarette smoke and alcohol may be an important component of the increased lung infections and chronic lung disease exacerbations observed in smoking persons who also consume alcohol.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Bovine Bronchial Epithelial Cells

Grossly healthy bovine lungs were obtained from a local slaughterhouse (ConAgra, Omaha, NE), and bronchi were isolated. Explants of ciliated bronchial epithelial cells were cultured after enzymatic digestion of the bronchi as previously described.7 Basal, nonciliated cells were collected through a mesh filter from the same preparation as previously described.15

Preparation of Ciliary Axonemes

Bovine ciliary axonemes were isolated with the use of the method of Hastie et al,17 processed, and characterized as previously described.18

Preparation of CSE

Bronchial epithelial cells and lung tissue slices were exposed in submerged cultures to liquid media extracts of cigarette smoke as previously described.19 In that previous study, it was determined that a 5% dilution of this cigarette smoke extract (CSE) was optimal for stimulating maximal PKC activity in the absence of any cell death. Likewise, we have shown that 100 mmol/L ethanol (a blood alcohol concentration clinically observed under conditions of alcohol abuse) is an optimal alcohol dose that affects cilia without cell toxicity.20

Mouse Smoke and Alcohol Co-Exposure Model

Healthy wild-type (C57Bl/6J) mice and PKCε knockout (PKCεKO) mice (B6.129S4-Prkcetm1Msg/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; stock number 004189) were group-housed (five mice per cage) and maintained in microisolator units at the animal facility of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Mice were allowed food and water ad libitum and were used experimentally at approximately 8 to 10 weeks of age. Animal handling was in accordance with guidelines set by the US Government Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research, and Training; the US Department of Agriculture implementing regulations, (9CFR), of the Animal Welfare Act; US Public Health Service Policy Assurance for the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals negotiated with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare; The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; and the UNMC/University of Nebraska Omaha Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines for the Care and Use of Live Vertebrate Animals. The UNMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all protocols. Mice were exposed to cigarette smoke via whole-body chamber, fed alcohol in their drinking water, or co-exposed to both with the use of a model previously characterized.6 In some cases, the order of smoke or alcohol as a first exposure was reversed with no change in the duration of exposure.

Health status is assessed on a quarterly basis at UNMC with the use of dirty-bedding exposure of sentinel mice. The following specific pathogens of laboratory mice are excluded from the animal facility: Sendai virus, pneumonia virus of mice, mouse hepatitis virus, minute virus of mice, Theiler's mouse encephalomyelitis virus/GDVII strain, respiratory enteric orphan virus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, mouse parvovirus, epizootic diarrhea virus of infant mice, parvovirus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, Hantavirus, mouse adenovirus, Ectromelia virus, mouse pneumonitis virus, polyoma virus, mouse thymic virus, mouse cytomegalovirus, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, and cilia-associated respiratory bacillus. In addition, sentinel mice are routinely tested for the presence of endo- and ecto-parasites (pinworms and fur mites), and these are excluded. Sporadic positive results for mouse norovirus have been detected in sentinel animals housed within this facility, but there is no direct evidence that colony mice were contaminated with the agent at the time of this study (data not shown). The facility does not test for lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus.

Tracheae from PKCδ knockout mice were obtained from the University of California Los Angeles as a gift from Dr. Steven Pandol.21 Wild-type controls were obtained concurrently from the same facility.

Preparation of Mouse Lung Slices

Precision-cut mouse lung slices were prepared as previously described22 with the use of the method of Delmotte and Sanderson.23

Preparation of Tracheal Rings

Tracheal rings were prepared as previously described.6

Quantitation of Ciliary Beating

Explants of ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells, tracheal ring epithelium, and precision-cut lung slices were measured for changes in cilia motility. CBF analysis and measurement of the total number of motile points during whole-field analysis were accomplished with the use of the Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis method as previously validated and characterized.24

PKC Activity Assay

Determination of PKC isoform catalytic activity was accomplished in fractionates from axonemes, cells, and tissues by direct isoform-specific substrate peptide phosphorylation assays as previously described.25

Translocation Inhibitor Peptide Production

PKCε translocation inhibitor peptide (ε V1-2) was obtained commercially (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA). In addition, two other carrier protein variants of this inhibitor were constructed at UNMC (gift of Dr. Sam Sanderson) to ensure cell permeability of the peptide. One contained a myristolated group and the other contained a Drosophila antennapedia peptide (R-Q-I-K-I-W-F-Q-N-R-R-M-K-W-K-K) to make it cell permeable as previously described.26 Cells were preincubated with the translocation inhibitors from 0.5 to 24 hours before experimental assay in the presence or absence of 50 μmol/L digitonin to maximize cell penetration.

Immunostaining

PKC was immunolocalized on bovine ciliary axonemes with the use of the method of Stout et al,27 using rabbit anti-PKCε obtained commercially from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Viability Assays

Cell and tissue viability was determined by lactate dehydrogenase activity assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). No significant lactate dehydrogenase release was detected in cells under any treatment condition. Experimental treatment and assays that used precision-cut mouse lung slices were not conducted until 1 week after slicing at which time lactate dehydrogenase levels had returned to baseline levels.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative experiments were performed in triplicate. All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 4.00 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego CA) and represented as mean ± SE. Data were analyzed for statistical significance with the use of one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing between each condition group. Significance was accepted at the 95% confidence interval.

Materials

Reference cigarettes (3R4F) were obtained from the University of Kentucky (Tobacco Health Research Institute, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY). Absolute ethanol was obtained from Pharmco-AAPER (Shelbyville, KY). Translocation inhibitor peptide was a gift from Dr. Steven Pandol (University of California Los Angeles). All other materials were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Results

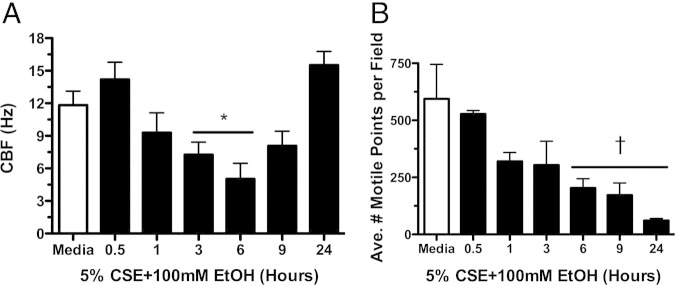

Smoke and Alcohol Co-Exposure Significantly Slow Cilia Beating in Vitro

To determine the effect of combined smoke and alcohol exposure on cilia beating in intact cells, primary cultures of ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to 5% CSE and 100 mmol/L ethanol for 30 minutes to 24 hours, and CBF was determined over time. CBF began to decrease by 1 hour with a significant (P < 0.05 versus time-matched media controls) decrease in CBF observed from 3 to 6 hours compared with media control (Figure 1A). CBF slowing continued such that there was a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in total number of motile points at 6 hours of treatment with smoke and alcohol (Figure 1B). A remaining small subset of ciliated cells could still be detected beating at 24 hours at a CBF no different from control. Co-exposure with CSE concentrations up to 20% and ethanol concentrations as low as 20 mmol/L showed similar effects (data not shown). Neither cigarette smoke alone (5% CSE) nor ethanol alone (100 mmol/L) decreased cilia beating (see Supplemental Figure S1, A-D, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Brief ethanol exposure (1 hour) transiently stimulated CBF. These data suggest that most ciliated cells slow and stop beating in response to the combination of smoke and alcohol.

Figure 1.

Smoke and alcohol slow cilia beat frequency (CBF). Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) and 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in liquid submerged in vitro cultures. CBF (A) and the average number of motile points per field of cells (B) were determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis. A representative media control (M199) is indicated by the white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). *P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points of 3 to 6 hours for CBF; †P < 0.01 versus control media at matched time points of 6 to 24 hours for average motile points.

Smoke and Alcohol Co-Exposure Activates PKCε Activity in Epithelial Cells

Because PKC has been implicated in cilia slowing, we assayed PKCε activity after smoke and alcohol exposures in ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells and found that the combination of 5% CSE plus 100 mmol/L ethanol significantly (P < 0.001 versus time-matched media controls) stimulated PKCε activity (Figure 2). PKCε activity was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased from 6 to 9 hours compared with media controls and returned to baseline levels by 24 hours. No activation of PKCε was observed under conditions of smoke alone or alcohol alone (see Supplemental Figure S2, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). No activity changes were observed in the other novel isoform found in bronchial epithelium, PKCδ, under treatment conditions of smoke, alcohol, or both (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that the smoke and alcohol stimulation of PKCε occurs before cilia slowing and that a decrease in PKCε precedes ciliostasis.

Figure 2.

Effect of combination smoke and alcohol on protein kinase C (PKC)ε activity. Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) and 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in submerged in vitro cultures. PKCε activity was assayed at various time points from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A representative media control (M199) is indicated by the white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). *P < 0.001 versus control media at matched time points of 1 to 3 hours; †P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points of 6 to 9 hours.

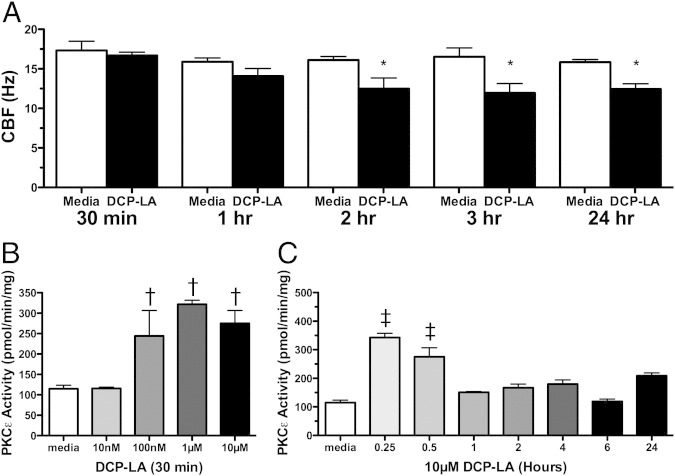

To further define a sequential effect for PKCε in regulating CBF, bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with a linoleic acid derivative, 8-[2-(2-pentylcyclopropylmethyl)-cyclopropyl]-octanoic acid (DCP-LA), a specific activator of PKCε. DCP-LA (10 μmol/L) decreased CBF at 2, 3, and 24 hours compared with baseline media controls at the same time points (Figure 3A). DCP-LA was capable of dose- and time-dependently activating PKCε before it slowed cilia (Figure 3, B and C). These findings implicate PKCε activation as an important upstream regulator of cilia slowing in the bronchial epithelial cell after combined smoke and alcohol exposure.

Figure 3.

Effect of a protein kinase C (PKC)ε activator on cilia beat. Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with 10 μmol/L 8-[2-(2-pentylcyclopropylmethyl)-cyclopropyl]-octanoic acid (DCP-LA) for 30 minutes to 24 hours in submerged in vitro cultures. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A) was determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis, and PKCε activity was determined for various concentrations (10 nmol/L to 10 μmol/L) of DCP-LA (B) and at various times (15 minutes to 24 hours) of 10 μmol/L DCP-LA (C). Media controls (M199) are indicated by white bars. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). *P < 0.01 versus control media at matched time points of 2 to 24 hours for CBF; †P < 0.05 versus control media at 30 minutes for 100 nmol/L to 10 μmol/L DCP-LA for PKCε activation; ‡P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points of 15 to 30 minutes for 10 μmol/L DCP-LA for PKCε activation.

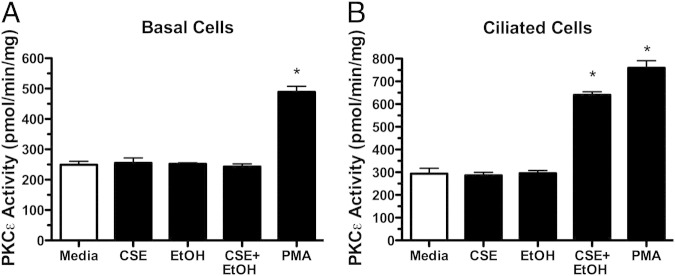

Combined Smoke and Alcohol Stimulation of PKCε Is Specific to Ciliated Epithelial Cells

The cellular specificity of the combination of cigarette smoke and alcohol effect on PKCε was examined in both ciliated and nonciliated bronchial epithelial cells to determine whether combined smoke- and alcohol-stimulated PKC activity was localized to the ciliated cells. When basal, nonciliated primary bovine bronchial epithelial cells were stimulated with the combination of 5% CSE and 100 mmol/L ethanol for 1 hour, no activation of PKCε was observed (Figure 4A). However, the nonselective classical and novel PKC isoform activating phorbol ester, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; 100 ng/mL), significantly activated PKCε in the basal cell. Smoke and alcohol failed to activate PKCε at any concentration (CSE 5% to 20% and ethanol 10 to 100 mmol/L) or time (1 to 24 hours) (data not shown). Conversely, ciliated cells from the same primary bovine preparations showed significant PKCε activation in response to smoke and alcohol (Figure 4B). Similar to PMA, 10 μmol/L DCP-LA stimulated PKCε activity in both basal and ciliated cells (data not shown). These data indicate that the action of smoke and alcohol on PKCε is specifically targeted to the kinase localized in the ciliated cell.

Figure 4.

Differential effects of smoke and alcohol on basal versus ciliated cells. Both nonciliated basal (A) and ciliated (B) primary bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated in submerged culture with M199 media (white bars), 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE), 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH), individually and in combination for 1 hour, and protein kinase C (PKC)ε activity assayed. As a positive control, cells were treated with 100 ng/mL phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) for 15 minutes, and PKCε activity was assayed. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). *P < 0.001 versus control media for PMA treatment in both cell types and smoke+EtOH in ciliated cells.

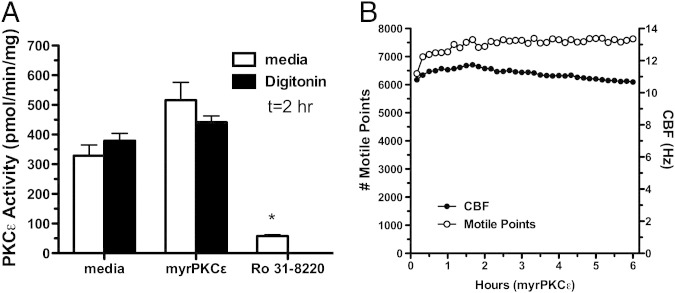

PKCε Activation-Induced Cilia Beating Is Not Translocation Dependent

To further characterize the presence of subcellular localized PKCε action in the ciliated cell, ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were pretreated with direct catalytic site inhibitors and translocation inhibitors of PKCε. In the ciliated cell, the novel PKCε inhibitor, Ro 31-8220 (10 μmol/L), decreases PKCε catalytic activity rates below that of baseline and leads to cilia slowing and ciliostasis.28 In contrast, the PKCε translocation inhibitor, (ε V1-2; 10 μmol/L), failed to significantly decrease PKCε activity (Figure 5A), slow CBF, and did not alter the number of motile points (Figure 5B) in the ciliated cell both in the presence and absence of a cell permeabilizing agent (digitonin). Two different soluble conjugates of the PKCε V1-2 translocation inhibitor peptide (myristolated peptide and Drosophila antennapedia peptide) were used without observing changes in kinase activity to control for cell permeability (data not shown). The use of 50 μmol/L digitonin to enhance peptide solubility did not alter these results (Figure 5A). These results show that the effect of PKCε activation on cilia is not regulated by translocation control, suggesting a directly localized action of PKCε on the cilium.

Figure 5.

Differential effects of translocation inhibitor versus catalytic site inhibitor on ciliated cell protein kinase C (PKC)ε and motility. Ciliated primary bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with 10 μmol/L myristolated PKCε translocation inhibitor peptide in the presence or absence of 50 μmol/L digitonin (black bars) or 10 μmol/L active site inhibitor Ro 31-8220 and PKCε activity at 2 hours (A) or number of motile points from 1 to 6 hours (B) assayed. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). *P < 0.001 versus control media for Ro 31-8220 treatment. CBF, ciliary beat frequency.

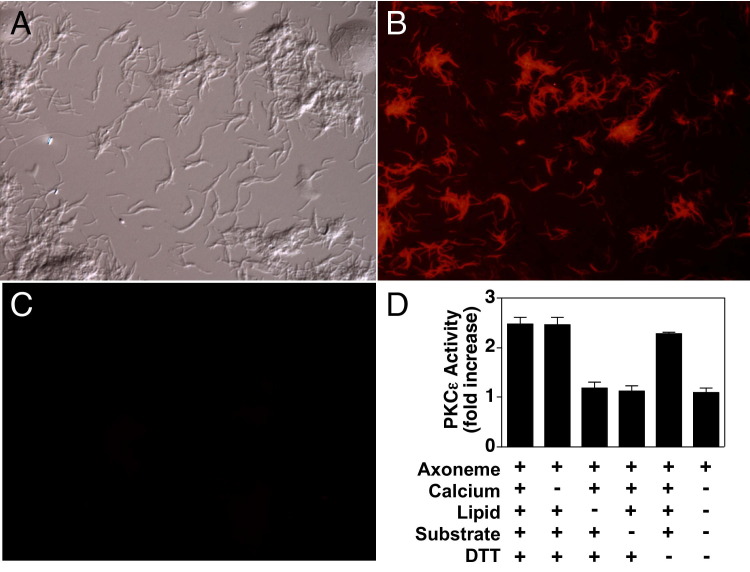

Catalytically Active PKCε Is Localized Directly on the Ciliary Axoneme

To confirm the localization of PKCε on the cilia, subcellular organelle extracts of ciliary axonemes were prepared and probed for the presence and activity of PKCε. Isolated bovine axonemes stained with antibodies to PKCε showed the presence of the isoenzyme throughout the hair-like structure of the axoneme (Figure 6, A and B). Isotype controls that used a nonspecific IgG in place of the anti-PKCε showed no nonspecific staining (Figure 6C). In addition to localizing PKCε protein in the isolated axonemes, we were able to measure PKCε activity in the isolated axonemes. Kinase activity assays of isolated axonemes extracted from unstimulated bovine tracheae showed the presence of a calcium-independent and lipid-dependent basal-level phosphorylation of a PKCε-specific substrate peptide (Figure 6D). These data indicate that catalytically active PKCε is localized directly on the ciliary axoneme.

Figure 6.

Localization of protein kinase C (PKC)ε directly on the isolated bovine trachea ciliary axoneme. Axonemes were visualized by differential interference contrast microscopy (A), stained with rabbit anti-PKCε antibodies (B) or nonspecific IgG (C), and visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Axonemes were also assayed for PKCε activity in the presence or absence of calcium, lipid, substrate, or dithiothrietol (DTT) (D).

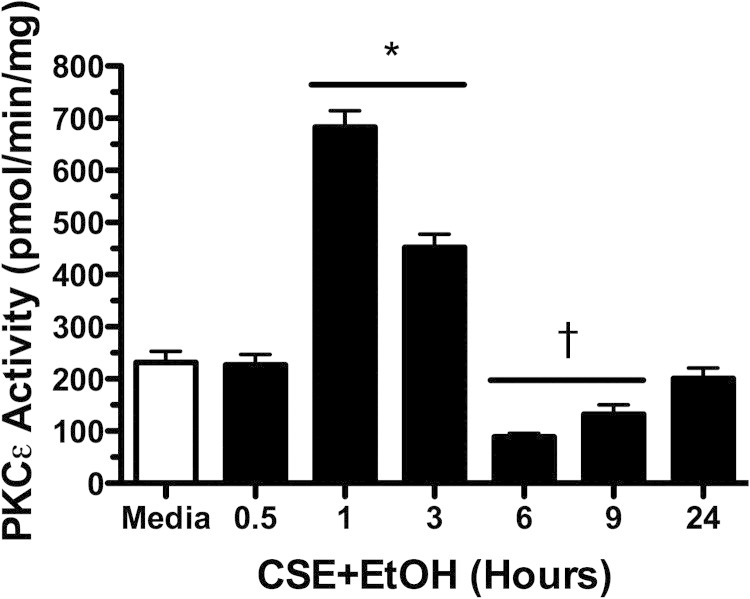

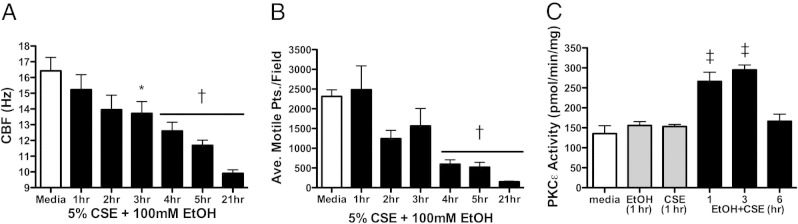

Smoke and Alcohol Effects on PKCε-Mediated Cilia Action in Lung

To show a lung-specific action of smoke and alcohol on cilia, precision-cut untreated C57Bl/6 naive mouse lung slices were treated with CSE, alcohol, or both in combination. A time-dependent decrease in CBF was observed in the large airways of mouse lung slices after smoke and alcohol co-exposure (P < 0.05) at 3 hours and continuing overnight (Figure 7A). In smoke-only exposure, no changes in CBF were observed at all time points compared with control (see Supplemental Figure S3A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Compared with media control (untreated slices), at 4 to 24 hours the number of motile points were markedly diminished in the larger airways after smoke and alcohol (Figure 7B; P < 0.01). In slices treated with alcohol alone, the number of motile points increased at 1 hour (P < 0.05) but was unchanged at all other time points compared with control (see Supplemental Figure S3B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Brief ethanol exposure (1 hour) stimulated CBF. Significant (P < 0.001) increases in PKCε activity were detected in mouse lung slices treated with smoke and alcohol before cilia slowing (Figure 7C), consistent with those observations made in isolated ciliated cells.

Figure 7.

Effect of combination smoke and alcohol on cilia in lung slices. Precision-cut mouse lung slices were treated with 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) and 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in submerged in vitro culture. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A) and the average number of motile points per field of cells (B) were determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis from 1 to 21 hours. Protein kinase C (PKC)ε activity was assayed from 1 to 6 hours (C). Representative media controls (M199) are indicated by the white bars. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). *P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points of 3 to 21 hours for CBF; †P < 0.01 versus control media at matched time points of 4 to 21 hours for average motile points; ‡P < 0.001 versus control media at matched time points of 1 to 3 hours.

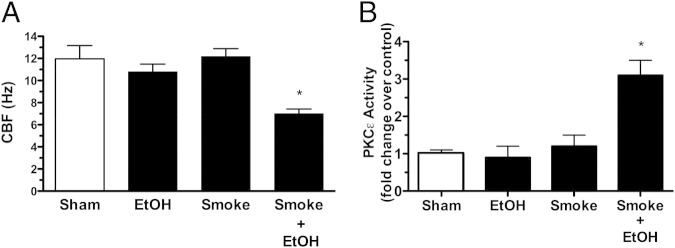

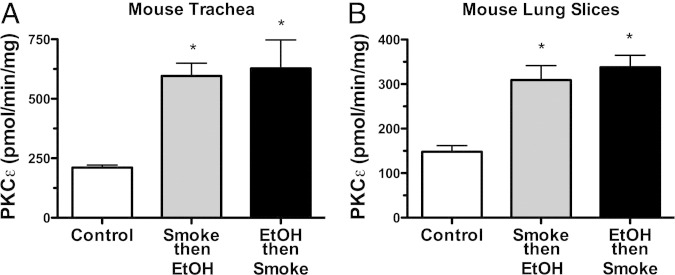

To establish in vivo relevance, we exposed wild-type C57Bl/6 mice to whole-body cigarette smoke chambers and added alcohol to their drinking water with the use of a previously established co-exposure model.6 Mice that were co-exposed to both cigarette smoke and alcohol showed a significant (P < 0.01) reduction in tracheal ring CBF (Figure 8A). No significant changes in CBF were observed in the tracheal cilia of mice exposed to only cigarette smoke or only fed alcohol in their drinking water. In those tracheal epithelial cells extracted from mice co-exposed to smoke and alcohol, PKCε was increased approximately threefold over the sham (air)-exposed mouse group (Figure 8B). This elevation in kinase activity was not observed in the tracheal epithelium of the alcohol-alone or smoke-alone exposure groups (Figure 8B) and was observed regardless of whether the mice were initially exposed to cigarette smoke followed by alcohol feeding, or if the animals began an alcohol feeding regimen followed by subsequent cigarette smoke exposure (Figure 9, A and B). A similar pattern of results for PKC activity (Figure 9) and CBF (data not shown) was also observed in mouse trachea and whole-lung slices regardless of the combination exposure sequence.

Figure 8.

Effect of in vivo smoke and alcohol exposure on cilia. Mice were either sham-treated (white bars) with air and water, whole body exposed to cigarette smoke (smoke), fed 20% alcohol (EtOH), or exposed to both alcohol and cigarette smoke in combination (smoke+EtOH) for 8 weeks. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A) and protein kinase C (PKC)ε activity (B) were assayed from tracheal epithelium. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = six mice per group). *P < 0.01 for smoke+EtOH-treated versus sham-treated mice.

Figure 9.

Sequence of in vivo smoke and alcohol co-exposure does not alter the effects on protein kinase C (PKC)ε. Mice were either whole-body smoke-exposed first followed by alcohol feeding (gray bars) or alcohol-fed first followed by whole-body smoke exposure (black bars) in vivo, and PKCε activity was measured in both tracheal epithelium (A) and precision-cut lung slices (B). Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 6 mice/group). *P < 0.01 for either smoke then EtOH-treated or EtOH then smoke-treated versus sham-treated mice.

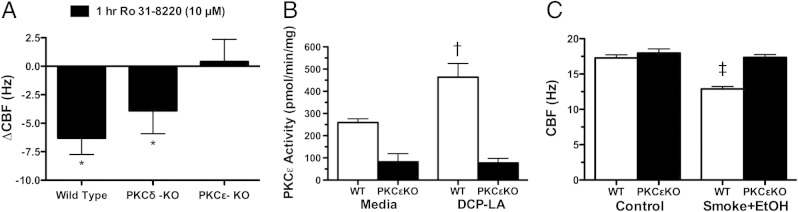

To confirm the pivotal role of PKCε in smoke and alcohol–induced ciliary slowing, we investigated the effect on CBF in PKCεKO mice. As expected, CBF significantly (P < 0.05) decreased in response to the novel PKC inhibitor, Ro 31-8220 (Figure 10A), in the tracheal rings cut from wild-type mice. However, no slowing in cilia beating or ciliostasis was observed from similarly treated PKCεKO mice. As an additional control, Ro 31-8220 effectively induced ciliostasis before ciliated cell detachment in the tracheal epithelium of PKCδ knockout mice but not in PKCεKO mice. In precision-cut mouse lung slices from PKCεKO mice, DCP-LA in situ-treated tissue did not stimulate PKCε activity (Figure 10B) or cause cilia slowing (not shown), validating the absence of PKCε activity in the PKCεKO mice. In keeping with these observations, the CBF decreases observed in response to the combination of in situ treatment of smoke and alcohol in the wild-type mouse lung slice is not detected in the PKCεKO mouse slices (Figure 10C). Neither 5% CSE nor alcohol alone slowed CBF from PKCεKO mouse slices (see Supplemental Figure S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Collectively, these data indicate the requirement for PKCε in the regulation of cilia slowing induced by the combined action of cigarette smoke and alcohol exposure.

Figure 10.

Effect of smoke and alcohol exposure on cilia from protein kinase C (PKC)ε knockout mice. Tracheal rings and lung slices were cut from mice that lacked PKCε expression. Change in ciliary beat frequency (CBF) in response to ex vivo 10 μmol/L Ro 31-8220 treatment (versus baseline CBF) in the trachea of wild-type, PKCε knockout (PKCεKO), and PKCδ knockout (PKCδ-KO) mice were assayed by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis (A). Lung slice PKCε activity in response to ex vivo treatment with 10 μmol/L 8-[2-(2-pentylcyclopropylmethyl)-cyclopropyl]-octanoic acid (DCP-LA) was assayed in wild-type (WT) and PKCεKO mice (B). Lung slice PKCε activity in response to in situ treatment with smoke and alcohol was assayed in WT and PKCεKO mice (C). Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 6). *P < 0.01 for changes in CBF in WT and PKCδKO mice in the presence versus absence of Ro 31-8220; †P < 0.001 for PKCε activation in WT versus PKCεKO mice in response to DCP-LA; ‡P < 0.001 for PKCε activation in WT versus PKCεKO mice in response to the combination of smoke+alcohol. EtOH, ethanol.

Discussion

In this study, the co-exposure of cigarette smoke and alcohol, but neither alone, resulted in a significant and rapid slowing in CBF, which in part depended on PKCε activation in the axoneme of the ciliated airway epithelial cell. Our results extend the studies by Wong et al14 in which a novel isoform of PKC was suggested to be responsible for the cilia slowing induced by neuropeptide Y. Our data establish that the calcium-independent action of the novel PKC isoform, PKCε, controls cilia beat slowing. PKCδ is the other novel PKC isoform in lung epithelium. It is implicated in the regulation of cytokine production in the lung.29 However, it does not appear to be involved in cilia slowing. We did not observe any changes in PKCδ activity in response to cigarette smoke and alcohol co-exposure (data not shown). Likewise, the cilia-slowing response remained normal in the PKCδ knockout mouse (Figure 10A). The next step is to identify the cilia substrate(s) for PKCε in response to smoke and alcohol and to determine the mechanism behind how such a phosphorylation event slows cilia beating. A 37-kDa membrane-associated substrate for PKC has been isolated in ovine cilium that is involved with PKC-mediated cilia slowing,8 but no such homologues have been shown in mice, bovines, or humans. Coupled with our previous finding that the ciliated cell lacks the PKCε-targeting protein RACK1, which facilitates translocation-activated kinase activity to its substrate,30 our present finding that PKCε activity can be identified directly on the ciliated axoneme suggests that cilia-localized substrate targets for PKCε are likely for the regulation of CBF. Cilia structural components regulating the mechanics of functional cilia slowing are not currently defined.

A novel finding that has emerged from this work is that a small subpopulation of cultured ciliated cells continue to beat at normal baseline frequency levels even after 24 hours of exposure to smoke and alcohol (Figure 1). This finding underscores the importance of examining large populations of motile cells with the use of a whole-field analysis approach to control for the number of motile points over time. Otherwise, analysis of the small subpopulation of motile cells after 24 hours of treatment would have masked our findings. This subpopulation of cells resistant to the cilia-slowing effects of smoke and alcohol may be attributed to tissue culture artifact. The cell explants were i) enzyme digested and re-attached to matrix and subsequently lost any directional organization and control, ii) submerged in liquid cultures, or iii) of bovine origin. In contrast to the cultured cells, mouse precision-cut slices do not show unresponsive subpopulation of cells because the intact ciliated epithelia are attached to native tissue with a directional architecture. Ciliated cells from trachea or large airways were observed to eventually detach, similarly to the detachment injury reported in long-term smoke-exposed mouse tissues.2

In a previous study of long-term smoke exposure, we had shown in an in vivo mouse model of cigarette smoke exposure that cilia slowing and detachment of ciliated cells takes place over a chronic exposure to cigarette smoke of 6 to 9 months.2 However, others have reported that shorter times of cigarette smoke exposure may enhance mucociliary transport.3 This discrepancy may be because of an early mechanical stimulation effect in response to particles in cigarette smoke. Similarly, we have observed that filterable cigarette smoke particles > 0.2 μm in size can stimulate ciliary axoneme bending in isolated cilia.31 However, in this study, short-term cigarette smoke exposure alone did not activate PKCε or alter CBF. Moreover, the combination of cigarette smoke and alcohol does not enhance cilia beating, but rather produces the unique and rapid effect of cilia slowing that otherwise would require a much longer exposure to just cigarette smoke alone.

The loss of total motile points is the result of both detached cells and/or complete ciliostasis. This is consistent with the PKCε inhibition-mediated detachment because of Ro 31-822028 because auto-downregulation of PKCε is observed temporally after smoke and alcohol activation of PKCε (Figure 2). Such an auto-downregulation response would be functionally equivalent to direct inhibition of the PKCε catalytic active site as accomplished with Ro 31-8220 treatment. Our current and previously published data28 support the conclusion that Ro 31-8220 induces the detachment of ciliated cells via the direct chemical inhibition of PKCε. Detaching and unattached ciliated cells beat slower because of the physical mechanics of cilia beat. Thus, the cilia slowing that precedes the detachment of a ciliated cell in response to PKCε inhibition would be indistinguishable from the active cilia slowing initiated by PKCε activation in the absence of ciliated cell detachment as that observed with smoke and alcohol treatment. Interestingly, no such detachment is observed when cells were treated with the PKCε translocation inhibitor as was observed with a catalytic site inhibitor. Phorbol esters and lipid activators (Figure 3) do not appear to stimulate ciliated cell detachment even though they both lead to CBF slowing. These observations suggest that a translocatable form of PKCε not regulating CBF and a cilia-localized form of PKCε susceptible to activation/inhibition regulation of cilia beat exist in airway epithelium. Clearly, a differential regulation of PKCε exists in basal versus ciliated epithelial cells. This is likely because the PKCε-targeting protein, RACK1, is expressed in basal nonciliated bronchial epithelial cells, but not in ciliated epithelial cells from the same tissue.30 Such compartmentalized regulation of kinase action may provide the specificity of cilia responses to external stimuli such as smoke and alcohol, leaving no such PKCε effect on basal airway epithelium.

A potential mechanism for cilia slowing due to smoke and alcohol–mediated cilia slowing observed in vivo may be related to the action of reactive aldehyde accumulation in the lung. Both ethanol metabolism and tobacco pyrrolysis result in the generation of malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde. Indeed, we have previously detected these reactive aldehydes in the lungs of mice co-exposed to cigarette smoke and alcohol.32 Of importance is the fact that neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol in high concentrations alone is sufficient to produce both the levels of malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde observed under co-exposure conditions. In addition, we have demonstrated significant concentrations of malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde (MAA) protein adduct formation in lungs, but only under conditions of smoke plus alcohol co-exposure.32 In vitro, MAA-adducted proteins bind to scavenger receptor A, resulting in the activation of PKC.33 In addition, direct lung instillation of MAA-adducted lung surfactant protein results in the activation of airway epithelial PKCε activation.22 Current studies are under way to characterize MAA-adducted proteins as ligands for scavenger receptor in airway epithelium and the in vivo effects of MAA-adducted protein on cilia beating to explore stable hybrid adduct formation as a mechanism for the cilia-slowing effects observed in response to combined smoke and alcohol exposure.

Distinct differences exist between the actions of combined smoke and alcohol versus ethanol only on cilia. Brief modest exposure to alcohol alone actually stimulates a rapid increase in CBF in both in vitro cell models34 and in vivo rodent models6 because of a transient elevation of nitric oxide. However, continued chronic alcohol exposure leads to a desensitization of cilia to further CBF stimulation by any cAMP-elevating agent such as β agonists.4,35 Although no significant slowing of cilia below baseline beating is observed with alcohol only treatment at any time point, combination smoke and alcohol exposure in vivo led to discernible and biologically relevant cilia slowing, particularly after a subsequent in vitro exposure of in vivo-treated tissues with a β agonist.6 Whether β agonists are capable of potentiating cilia slowing induced by smoke and alcohol has yet to be determined.

In summary, we found that co-exposure to cigarette smoke and alcohol resulted in a rapid slowing of CBF via a PKCε-dependent manner. These observations are consistent with our preclinical rodent models that established that mucociliary clearance is significantly diminished under conditions of alcohol and cigarette smoke.5,6 These results may have clinical importance because most persons with alcohol use disorders smoke cigarettes.36,37 Persons with alcohol use disorders have an increased risk in both the occurrence and severity of lung infections,38 which could potentially affect infection-mediated exacerbations of chronic inflammatory lung diseases such as bronchitis, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Future research should examine lung infections and chronic lung disease exacerbations within the context of smoke and alcohol co-exposure. Given that lung defense involves both innate and adaptive immune defenses to inhaled pathogens, the effect of combined cigarette smoke and alcohol effects should likely be considered for those lung defenses downstream of mucociliary clearance as well.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants R37AA008769 (J.H.S.), R01AA017993-S1 and R01AA017993 (T.A.W.), and K08AA019503 (K.L.B.), and NIH/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants R01ES019325 and K08ES015522-S1 (J.A.P.); by Department of Veterans Affairs grant I01BX000728 (T.A.W.); and with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System (Omaha, NE).

CME Disclosure: The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest to disclose.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.022.

Supplementary data

Neither cigarette smoke alone nor alcohol alone decrease cilia beating. Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with either 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in liquid-submerged in vitro cultures. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A and C) and the average number of motile points per field of cells (B and D) were determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis. A representative media control (M199) is indicated by a white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). ⁎P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points of 3 to 6 hours.

Neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol alone activates protein kinase C (PKC)ε. Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with either 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE; A) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH; B) in submerged in vitro cultures. PKCε activity was assayed at various time points from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A representative media control (M199) is indicated by a white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9).

Neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol alone decreases cilia beating in lung slices. Precision-cut mouse lung slices were treated with either 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in submerged in vitro culture. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A) and the average number of motile points per field of cells (B) were determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis from 1 to 21 hours. Representative media controls (M199) are indicated by a white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). ⁎P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points for average motile points.

Neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol exposure alone slows cilia beat frequency (CBF) from protein kinase C (PKC)ε knockout (PKCεKO) mice. Lung slices were obtained from mice lacking PKCε expression. Changes in CBF in response to in vitro 5% cigarette smoke extract (Smoke) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) treatment for 4 hours (versus baseline CBF) in wild-type and PKCεKO mice trachea were assayed by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 6).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged >or=18 years — United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simet S.M., Sisson J.H., Pavlik J.A., Devasure J.M., Boyer C., Liu X., Kawasaki S., Sharp J.G., Rennard S.I., Wyatt T.A. Long-term cigarette smoke exposure in a mouse model of ciliated epithelial cell function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:635–640. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0297OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coote K., Nicholls A., Atherton H.C., Sugar R., Danahay H. Mucociliary clearance is enhanced in rat models of cigarette smoke and lipopolysaccharide-induced lung disease. Exp Lung Res. 2004;30:59–71. doi: 10.1080/01902140490252885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyatt T.A., Sisson J.H. Chronic ethanol downregulates PKA activation and ciliary beating in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L575–L581. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vander Top E.A., Wyatt T.A., Gentry-Nielsen M.J. Smoke exposure exacerbates an ethanol-induced defect in mucociliary clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:882–887. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164364.35682.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott M.K., Sisson J.H., Wyatt T.A. Effects of cigarette smoke and alcohol on ciliated tracheal epithelium and inflammatory cell recruitment. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:452–459. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0440OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyatt T.A., Spurzem J.R., May K., Sisson J.H. Regulation of ciliary beat frequency by both PKA and PKG in bovine airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L827–L835. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.4.L827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salathe M., Pratt M.M., Wanner A. Protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of a ciliary membrane protein and inhibition of ciliary beating. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:1211–1220. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fishaut M., Schwartzman J.D., McIntosh K., Mostow S.R. Behavior of respiratory syncytial virus in piglet tracheal organ culture. J Infect Dis. 1978;138:644–649. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.5.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien D.W., Morris M.I., Lee M.S., Tai S., King M. Ophiopogon root (Radix Ophiopogonis) prevents ultra-structural damage by SO2 in an epithelial injury model for studies of mucociliary transport. Life Sci. 2004;74:2413–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyatt T.A., Sisson J.H., Von Essen S.G., Poole J.A., Romberger D.J. Exposure to hog barn dust alters airway epithelial ciliary beating. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1249–1255. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J.H., Takeno S., Osada R., Ueda T., Yajin K. Modulation of ciliary activity by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cultured sinus epithelial cells: Possible roles of nitric oxide. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 2000;49:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sisson J.H., Tuma D.J. Vapor phase exposure to acetaldehyde generated from ethanol inhibits bovine bronchial epithelial cell ciliary motility. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1252–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong L.B., Park C.L., Yeates D.B. Neuropeptide Y inhibits ciliary beat frequency in human ciliated cells via nPKC, independently of PKA. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C440–C448. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyatt T.A., Ito H., Veys T.J., Spurzem J.R. Stimulation of protein kinase C activity by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L1007–L1012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slager R.E., Allen-Gipson D.S., Sammut A., Heires A., Devasure J., Von Essen S.G., Romberger D.J., Wyatt T.A. Hog barn dust slows airway epithelial cell migration in vitro through a PKC{alpha}-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1469–L1474. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00274.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hastie A.T., Dicker D.T., Hingley S.T., Kueppers F., Higgins M.L., Weinbaum G. Isolation of cilia from porcine tracheal epithelium and extraction of dynein arms. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1986;6:25–34. doi: 10.1002/cm.970060105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyatt T.A., Forget M.A., Adams J.M., Sisson J.H. Both cAMP and cGMP are required for maximal ciliary beat stimulation in a cell-free model of bovine ciliary axonemes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L546–L551. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00107.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyatt T.A., Schmidt S.C., Rennard S.I., Sisson J.H. Acetaldehyde-stimulated PKC activity in airway epithelial cells treated with smoke extract from normal and smokeless cigarettes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;225:91–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyatt T.A., Forget M.A., Sisson J.H. Ethanol stimulates ciliary beating by dual cyclic nucleotide kinase activation in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63475-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thrower E.C., Wang J., Cheriyan S., Lugea A., Kolodecik T.R., Yuan J., Reeve J.R., Jr, Gorelick F.S., Pandol S.J. Protein kinase C delta-mediated processes in cholecystokinin-8-stimulated pancreatic acini. Pancreas. 2009;38:930–935. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b8476a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyatt T.A., Kharbanda K.K., McCaskill M.L., Tuma D.J., Yanov D., Devasure J., Sisson J.H. Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde-adducted protein inhalation causes lung injury. Alcohol. 2012;46:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delmotte P., Sanderson M.J. Ciliary beat frequency is maintained at a maximal rate in the small airways of mouse lung slices. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:110–117. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0417OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sisson J.H., Stoner J.A., Ammons B.A., Wyatt T.A. All-digital image capture and whole-field analysis of ciliary beat frequency. J Microsc. 2003;211:103–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wyatt T.A., Slager R.E., Heires A.J., Devasure J.M., Vonessen S.G., Poole J.A., Romberger D.J. Sequential activation of protein kinase C isoforms by organic dust is mediated by tumor necrosis factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:706–715. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0065OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satoh A., Gukovskaya A.S., Nieto J.M., Cheng J.H., Gukovsky I., Reeve J.R., Jr, Shimosegawa T., Pandol S.J. PKC-delta and -epsilon regulate NF-kappaB activation induced by cholecystokinin and TNF-alpha in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G582–G591. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00087.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stout S.L., Wyatt T.A., Adams J.J., Sisson J.H. Nitric oxide-dependent cilia regulatory enzyme localization in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:433–442. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7089.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slager R.E., Sisson J.H., Pavlik J.A., Johnson J.K., Nicolarsen J.R., Jerrells T.R., Wyatt T.A. Inhibition of protein kinase C epsilon causes ciliated bovine bronchial cell detachment. Exp Lung Res. 2006;32:349–362. doi: 10.1080/01902140600959630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y., He D., Saatian B., Watkins T., Spannhake E.W., Pyne N.J., Natarajan V. Regulation of lysophosphatidic acid-induced epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and interleukin-8 secretion in human bronchial epithelial cells by protein kinase Cdelta: Lyn kinase, and matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19501–19511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511224200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slager R.E., Devasure J.M., Pavlik J.A., Sisson J.H., Wyatt T.A. RACK1, a PKC targeting protein, is exclusively localized to basal airway epithelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:7–14. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7249.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarette C.R., Sisson J.H., Nance E., Allen-Gipson D.S., Hanes J., Wyatt T.A. Particulate matter in cigarette smoke increases ciliary axoneme beating through mechanical stimulation. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2012 doi: 10.1089/jamp.2011.0890. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCaskill M.L., Kharbanda K.K., Tuma D.J., Reynolds J., DeVasure J., Sisson J.H., Wyatt T.A. Hybrid malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde protein adducts form in the lungs of mice exposed to alcohol and cigarette smoke. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1106–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wyatt T.A., Kharbanda K.K., Tuma D.J., Sisson J.H., Spurzem J.R. Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts decrease bronchial epithelial wound repair. Alcohol. 2005;36:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sisson J.H. Ethanol stimulates apparent nitric oxide-dependent ciliary beat frequency in bovine airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L596–L600. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.4.L596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wyatt T.A., Gentry-Nielsen M.J., Pavlik J.A., Sisson J.H. Desensitization of PKA-stimulated ciliary beat frequency in an ethanol-fed rat model of cigarette smoke exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:998–1004. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000130805.75641.F4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller N.S., Gold M.S. Comorbid cigarette and alcohol addiction: epidemiology and treatment. J Addict Dis. 1998;17:55–66. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sisson J.H., Stoner J.A., Romberger D.J., Spurzem J.R., Wyatt T.A., Owens-Ream J., Mannino D.M. Alcohol intake is associated with altered pulmonary function. Alcohol. 2005;36:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamble L., Mason C.M., Nelson S. The effects of alcohol on immunity and bacterial infection in the lung. Med Mal Infect. 2006;36:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Neither cigarette smoke alone nor alcohol alone decrease cilia beating. Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with either 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in liquid-submerged in vitro cultures. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A and C) and the average number of motile points per field of cells (B and D) were determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis. A representative media control (M199) is indicated by a white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). ⁎P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points of 3 to 6 hours.

Neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol alone activates protein kinase C (PKC)ε. Primary ciliated bovine bronchial epithelial cells were treated with either 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE; A) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH; B) in submerged in vitro cultures. PKCε activity was assayed at various time points from 30 minutes to 24 hours. A representative media control (M199) is indicated by a white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9).

Neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol alone decreases cilia beating in lung slices. Precision-cut mouse lung slices were treated with either 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) in submerged in vitro culture. Ciliary beat frequency (CBF; A) and the average number of motile points per field of cells (B) were determined by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis from 1 to 21 hours. Representative media controls (M199) are indicated by a white bar. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 9). ⁎P < 0.05 versus control media at matched time points for average motile points.

Neither cigarette smoke nor alcohol exposure alone slows cilia beat frequency (CBF) from protein kinase C (PKC)ε knockout (PKCεKO) mice. Lung slices were obtained from mice lacking PKCε expression. Changes in CBF in response to in vitro 5% cigarette smoke extract (Smoke) or 100 mmol/L ethanol (EtOH) treatment for 4 hours (versus baseline CBF) in wild-type and PKCεKO mice trachea were assayed by Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis. Data are shown as means ± SEs (n = 6).