Abstract

Cellular Stress Response 1 (CSR1) is a tumor suppressor gene that is located at 8p21, a region that is frequently deleted in prostate cancer as well as a variety of human malignancies. Previous studies have indicated that the expression of CSR1 induces cell death. In this study, we found that CSR1 interacts with X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP), using yeast two-hybrid screening analyses. XIAP overexpression has been found in many human cancers, and forced expression of XIAP blocks apoptosis. Both in vitro and in vivo analyses indicated that the C-terminus of CSR1 binds XIAP with high affinity. Through a series of in vitro recombinant protein-binding analyses, the XIAP-binding motif in CSR1 was determined to include amino acids 513 to 572. Targeted knock-down of XIAP enhanced CSR1-induced cell death, while overexpression of XIAP antagonized CSR1 activity. The binding of CSR1 with XIAP enhanced caspase-9 and caspase-3 protease activities, and CSR1-induced cell death was dramatically reduced on expression of a mutant CSR1 that does not bind XIAP. However, a XIAP mutant that does not interact with caspase-9 had no impact on CSR1-induced cell death. These results suggest that cell death is induced when CSR1 binds XIAP, preventing the interaction of XIAP with caspases. Thus, this study may have elucidated a novel mechanism by which tumor suppressors induce cell death.

Cellular Stress Response 1 (CSR1) is a stress response gene located at 8p21, a region frequently deleted in prostate cancer and several other human malignant tumors.1–5 Homozygous deletion of CSR1 in prostate cancer is rare.6 However, the promoter/exon 1 region of CSR1 is frequently methylated in prostate cancer,6 and this methylation is associated with prostate cancer relapse. Forced expression of CSR1 in prostate cancer cell lines such as PC3, LNCaP, and DU145 inhibits colony formation, anchorage-independent growth, and invasion. Similarly, following forced expression of CSR1 in PC3 and DU145 xenograft mouse models, tumor volume and metastasis are decreased, and the mice have higher survival rates. A recent study suggested that CSR1 induces apoptosis and necrotic cell death by inhibiting polyadenylation of RNA through redistribution of a critical polyadenylation enzyme, CPSF3.7 However, cell death induction by CSR1 may not be explained solely by the inhibition of CPSF3, as the extent of cell death induced by CSR1 appeared to be more extensive than the reduction of polyadenylated mRNA would warrant.

An X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) is a crucial inhibitor of caspase-9, -3, and -7,8–10 and is ubiquitously expressed in almost all adult and fetal tissues. XIAP contains three baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domains, a RING-finger domain conferring ubiquitin protein ligase activity, and a ubiquitin-binding domain. XIAP overexpression is found in many human malignant samples, and forced expression of XIAP blocks apoptosis.9 It was shown that the mechanism of binding between the BIR domains of XIAP and the IAP-binding motif in the catalytic sites of caspases is two sited, facilitating potent inhibition.8,10 The caspase inhibitory activity of XIAP is regulated by several mitochondria molecules such as HtrA2 and SMAC.11–13 These molecules contain the conserved IAP-binding motif, and on release from the mitochondria, compete with caspases for XIAP binding, thus relieving caspases from XIAP inhibition. However, little is known about cytosolic or membranous inhibitors of XIAP. In this study, we showed that CSR1, a scavenger membranous protein, binds XIAP with high affinity on induction of expression, and prevents XIAP-inhibition of caspase activity, leading to apoptosis of CSR1-expressing cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture

Prostate cancer cell lines, DU145 and PC3, and an immortalized prostate epithelial cell line, RWPE-1, were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) in 2007. These cell lines underwent one cycle of growth before being stored in liquid nitrogen until needed. Cells were used for transfections within 2 weeks of thawing. DU145 cells were cultured in modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and PC3 cells were cultured in F12K (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cellgro, Manassas, VA). RWPE-1 cells were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium supplemented with 0.05 mg/mL bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/mL recombinant epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen). All cell lines were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell-permeable Caspase-9 Inhibitor II was obtained from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, CA).

Plasmid Construction

For construction of pBD-CSR1c fusion proteins, a mutagenic primer set (5′-TGTGGCCTATAATCATATGAATGTCACCATCCTACGAGGTGCC-3′ and 5′-TTCATTTCAAGCAAAGTCGACGCCTGGATCTGCTCTGCGCCCCTC-3′) was designed to create two restriction sites, NdeI and SalI, in the C-terminus (156 amino acids) of CSR1 so that the PCR product could be ligated into a pGBK7T vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). A PCR reaction was performed on cDNA template isolated from a normal prostate sample (Clontech), and the PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 1 minute followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds and 68°C for 3 minutes, and a final extension step for 3 minutes at 68°C. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and SalI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), gel purified, and ligated into a similarly digested pGBKT7 vector. The fusion protein contained 156 amino acids from the CSR1 C-terminus. The construct was transformed into One Shot competent cells (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was extracted from selected transformed cells and digested with NdeI and SalI to detect the presence of the insert. The coding frame was confirmed by automated sequencing. Similar procedures were performed for pBD-CSR1F and pAD-XIAP construction, except using the following primer pairs: 5′-GATATCATATGAAAGTGAGGTCGGCCGGC-3′/5′-GATATGTCGACGTCAGTAGAAGCTCT GGCTTCC-3′ for pBD-CSR1F, and 5′-GATATCATATGATGACTTTTAACAGTTTTGAA-3′/5′-GATATCTCGAGTTTAAGACATAAAAATTTTTTGCTTG-3′ for pAD-XIAP. The construction of pGST-CSR1c and corresponding mutants was described previously.7

The construction of pCDNA4-CSR1 is described elsewhere.7 To construct pCDNA4-CSR1▵512–573, mutagenesis PCR was performed. An upstream CSR1 fragment was generated with the following primer set: 5′-GATATCTTAAGACCATGGAAGTGAGGTCGGC-3′/5′-GTTCACCCTTAGGCCCCATAGGGCCCCTTTCTCCCACA-3′, and a downstream CSR1 fragment was generated with the following primer set: 5′-GATATGCGGCCGCCAGTAGAAGCTCTGGCTTCCTG-3′/5′-TGTGGGAGAAAGGGGCCCTATGGGGCCTAAGGGTGAAC-3′. These PCR products were combined and reamplified by PCR using the following primer set: 5′-GATATCTTAAGACCATGGAAGTGAGGTCGGC-3′/5′-GATATGCGGCCGCCAGTAGAAGCTCTGGCTTCCTG-3′. The PCR product was then digested with AflII and XhoI, and ligated into a similarly digested pCDNA4 vector.

Yeast Transformation and Library Screening

The yeast AH109 competent cell preparation was described previously.14 In 0.6 mL of PEG/LiAc, 100 μl of freshly prepared AH109 competent cells were mixed with plasmid pGBKT7-CSR1F (0.25 to 0.50 μg) plus 0.5 μg of plasmid DNA from prostate cDNA library constructed in pACT2, and the mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 minutes. After this initial incubation with plasmid DNA, the cell solution was combined with 70 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated at 42°C for 15 minutes. The cells were pelleted, resuspended in 0.5 mL of YPDA medium, and plated on minimum synthetic dropout medium agar plates of increasing nutrient stringency. The transformants were plated directly to low-, medium-, or high-stringency medium plates, or the colonies grown on the low (SD/-Leu/-Trp) and medium (SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His) stringency plates were transferred to high-stringency plates (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp and X-α-Gal). All colonies were subjected to the colony-lift filter β-galactosidase assay as described previously.15 pBD-53 and pAD-T antigen were cotransformed into AH109 and used as a positive control, and pBD-Lamin C was cotransformed with pAD-T and used as a negative control. PCL1 transformed into AH109 was used as a positive control for the galactosidase assay.

Validation of Protein Interactions in AH109

Plasmid DNA from positive clones (blue colonies on the high-stringency plate) was isolated from yeast and transformed into Escherichia coli. E. coli were then selected with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) to obtain gene-ACT2 fusion proteins interacting with the bait-domain fusion protein. To perform validation, cDNA of XIAP was ligated into pACT2 in frame. The pAD-XIAP DNA was then cotransformed with pBD-CSR1c or pBD-CSR1F into AH109 yeast cells and grown on an SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp high-stringency medium. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed by colony-lift filter in cells that grew in this medium.

Glutathione S-Transferase Fusion Protein Pull-Down

Cells were grown in 5 mL of Luria broth (ampicillin, 100 μg/mL) overnight at 37°C. Cells were then diluted 20-fold in Luria broth, and grown with shaking to OD 0.6 to 1.0. Protein expression was induced by isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (final concentration, 1 mmol/L) for 3 hours, and then cells were pelleted, resuspended in 1X PBS, and sonicated for 2 minutes. The proteins were solubilized in 1% Triton X-100. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 5 minutes. The GST and GST-CSR1c fusion proteins were purified with a Glutathione Sepharose 4B column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The PC3 cell protein extract was preincubated with the column for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the flow-through was collected after spinning at 3000 × g for 1 minute. The flow-through cell lysates were then incubated with GST fusion protein-packed Glutathione Sepharose 4B at 4°C for 2 hours. The column was spun at 3000 × g at room temperature for 1 minute and washed twice with PBS. The protein was eluted from the column with 40 μl of SDS-PAGE gel sample loading dye. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were subsequently conducted.

Immunofluorescence Staining

RWPE1 cells were cultured on chamber slides for 24 h, before slides were washed with PBS three times. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing the slides twice with PBS, the cells were blocked with 10% donkey serum with 0.4% Triton X-100. The cells were then incubated with rabbit antisera against CSR1 and goat antisera against XIAP (Santa Cruz Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) at room temperature for 1 hour. The slides were washed twice with PBS. Donkey anti-rabbit (fluorescein-conjugated) and donkey anti-goat (rhodamine-conjugated) secondary antibodies were added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The slides were then washed with PBS twice before the addition of DAPI. After additional washes with PBS, slides were mounted with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). Immunofluorescence staining was examined under a confocal microscope.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis of Apoptotic Cells

Cells transfected with inducible CSR1 clones were plated and treated with tetracycline (5 μg/mL) as described above. For UV treatment, RWPE1 cells were irradiated in a Stratalinker UV box with a dosage of 16.7 mj/m2. Cell death was analyzed 2 hours after UV treatment. These cells were trypsinized and washed twice with cold PBS. The cells were then resuspended in 100 μl of annexin binding buffer (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and incubated with 5 μl of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated annexin V and 1 μl of propidium iodide (PI; 100 μg/mL) for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature. The binding assays were terminated by addition of 400 μl of cold annexin binding buffer. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed in a BD-LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Sciences, San Jose, CA). The fluorescence stained cells were analyzed at 530 nm (FL1) and >575 nm (FL3). The negative control, cells incubated without Alexa Fluor 488 or PI, was used to establish the background setup in the acquisition. Cells stained with annexin V only or PI only were used for calibration and compensation before the acquisition. UV-treated cells were used as positive controls for the apoptotic cells. For each acquisition, 10,000 to 20,000 cells were sorted based on the fluorescence color of the cells: only green (apoptotic cells), only red, both red and green (late apoptotic stage or dead cells), or no color (live cells). WinMDI 2.9 software was used to further analyze the data. For siRNA analysis, 125 pmol of siRNA specific for XIAP (5′-GAAUAAGAAGCAUCAUACUAUAACT-3′/5′-AGUUAUAGUAUGAUGCUUCUUAUUCUU-3′), or CSR1 (5′-UUGGAUUCCUUCCAGGCUGCRUCCUG-3′/5′-CAGGAGCAGCCUGGAAGGAAUCCAA-3′), or non-specific control (5′-UAAUGUAUUGGAACGCAUAUU-3′/5′-UAUGCGUUCCAAUACAUUA-3′) was transfected into PWC1 cells using the Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Kit (Invitrogen,). Immunoblots and FACS analyses were performed 24 hours after transfection.

Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 Activity Assays

To investigate the protease activity of caspase-9, the Caspase-9/Mch6 Colorimetric Assay Kit from MBL International (Woburn, MA) was used. Briefly, WCSR1 cells were treated with or without tetracycline (5 μg/mL) for 3 days, and then lysed with RIPA buffer. Caspase-9 was then immunoprecipitated with mouse monoclonal antibody specific for caspase-9. The caspase-9/Mch6 colorimetric assay was performed by adding LEHD-pNA substrates to a final concentration of 200 μmol/L in a reaction volume of 50 μl. Protease assays were carried out at 37°C for 2 hours. The reaction was spun at 5000 × g, and protease activity was quantified in a spectrophotometer at 400 nmol/L. Immunoprecipitates without primary antibody were used as negative controls. For caspase-3 activity assays, the cell lysate of each sample was transferred to a 96-well black plate, and 5 μl of caspase-3 substrate (DEVD-AFC) and 50 μl of reaction buffer were added to each reaction. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, caspase-3 activity was quantified in a fluorometer at 400 nm/505 nm. Experiments with caspase-3 inhibitor or without caspase-3 substrate were used as controls.

Results

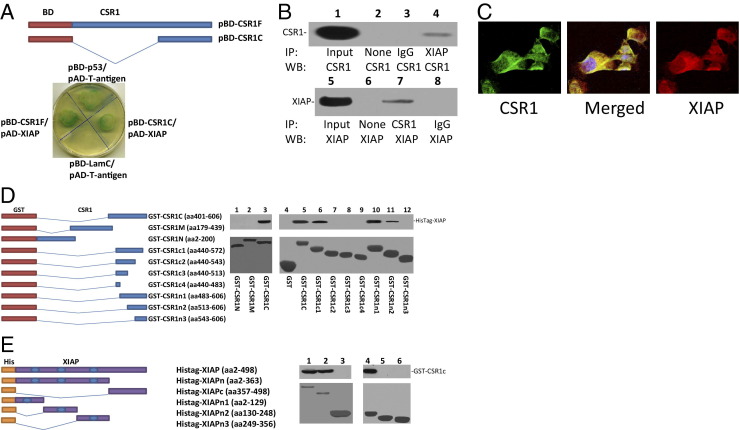

The mechanism of CSR1 tumor suppressor activity remains to be elucidated. To investigate the CSR1 signaling pathway that leads to suppression of tumor growth, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen on a prostate pACT2-cDNA library using pBD-CSR1F as a probe. Forty-five colonies that grew on the SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp nutrient-selective medium plate and were positive for X-α-Gal hydrolysis were identified. After eliminating redundant clones, 26 unique positive clones were identified. One of these clones was identified as XIAP. To validate the interaction of CSR1 and XIAP, XIAP cDNA was ligated into the pACT2 vector in frame with the activation domain of GAL4 to generate pAD-XIAP. This construct was then cotransfected with pBD-CSR1F into yeast AH109 cells and grown in SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp, and tested for galactosidase activity. As shown in Figure 1A, yeast harboring either the full-length CSR1 or the C-terminus of CSR1 grew on the stringent nutrient selective medium plate and had galactosidase activity, whereas yeast harboring laminin C and T-antigen (negative control) failed to grow under these conditions.

Figure 1.

The C-terminus of CSR1 binds XIAP. A: Constructs of full-length CSR1 (pBD-CSR1F) and the CSR1 C-terminus (pBD-CSR1c) bait domains for yeast two-hybrid analysis. Yeast cotransformed with pBD-CSR1F and pBD-CSR1c with pAD-XIAP were grown on an SD agar plate with high-stringency nutrient selection (SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade). B: Coimmunoprecipitation of XIAP or CSR1 using antibodies specific for CSR1 or XIAP. Images represent the immunoprecipitates separated by SDS-PAGE and incubated with the indicated antibodies. C: Immunofluorescence staining of RWPE-1 cells with antibody against XIAP (red) b and antibody against CSR1 (green). D: GST-fusion proteins were used to map the XIAP-binding motif of CSR1. Left: CSR1 deletion mutants with GST expression vectors. Right: Representative binding assays performed with GST or GST-CSR1 deletion mutants and XIAP from PC3 cell (lanes 1 to 3) or HisTag-XIAP (lanes 4 to 12) lysate. Top panel: Immunoblots with antibodies specific for XIAP. Bottom panel: Coomassie staining of fusion proteins. E: Fusion proteins were used to map the CSR1-binding motif of XIAP. Left: XIAP deletion mutants with His-tag expression vectors. Right: Representative binding assays performed with HisTag-XIAP or deletion mutants and GST-CSR1c. Top panel: Immunoblots with antibodies specific for the CSR1 C-terminus. Bottom panel: Coomassie staining of proteins. Lane 1, HisTag-XIAP; lane 2, HisTag-XIAPn; lane 3, HisTag-XIAPc; lane 4, HisTag-XIAPn1; lane 5, HisTag-XIAPn2; and lane 6, HisTag-XIAPn3.

To investigate whether the binding of CSR1 and XIAP occurs in vivo, coimmunoprecipitation of CSR1 and XIAP was performed on protein extract from RWPE1 cells, an immortalized prostate epithelial cell line. CSR1 and XIAP were coimmunoprecipitated when either anti-CSR1 or anti-XIAP antibodies were used (Figure 1B). Immunofluorescence staining of CSR1 and XIAP suggests that CSR1 and XIAP are co-localized in the cytoplasm and plasma membrane (Figure 1C). To examine whether CSR1 binds XIAP in vitro, fragments of CSR1 were ligated into pGEX5x in frame to create GST-CSR1 fusion proteins. GST-CSR1c (C-terminus of CSR1) bound XIAP, whereas the N-terminus and the mid-segment of CSR1 did not (Figure 1D). Subsequently, a series of CSR1 C-terminus deletion mutants were made. The binding analyses of XIAP with these mutants revealed that the binding motif is located at amino acids 513 to 572, as all mutants containing this sequence bound XIAP, whereas mutants without this sequence failed to bind XIAP (Figure 1, D and E).

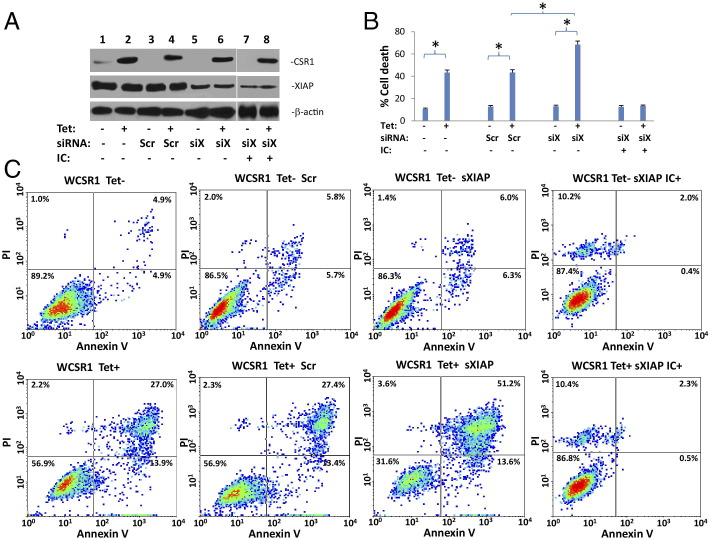

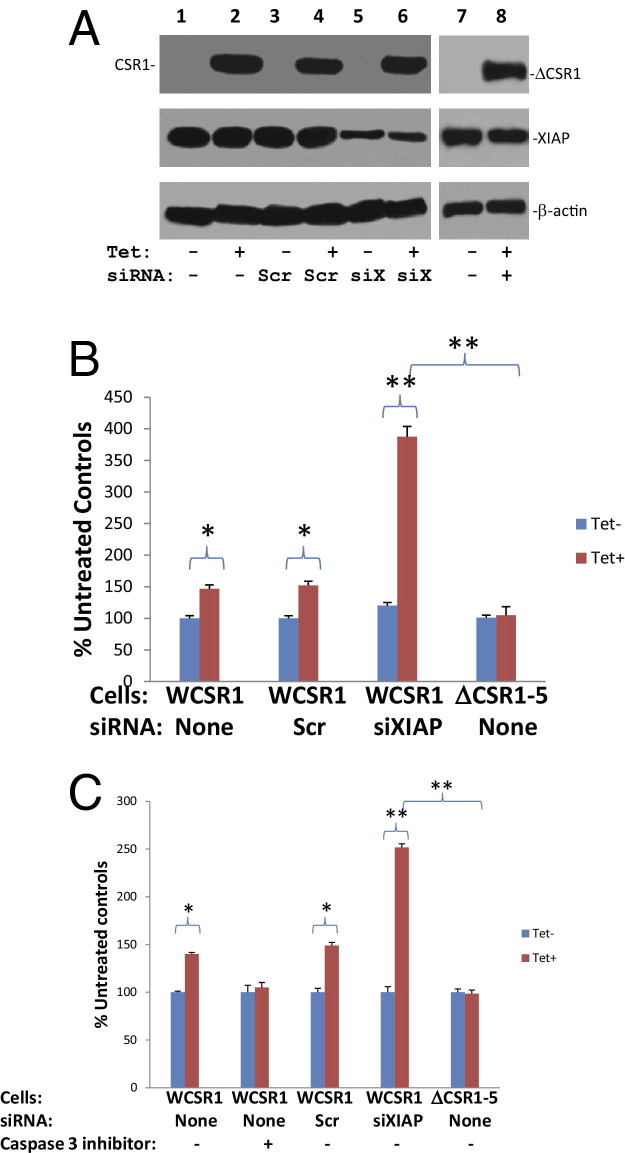

XIAP is a critical inhibitor of apoptosis, so we next investigated the role of XIAP in CSR1-induced cell death. As shown in Figure 2, A and B, induction of CSR1 expression in PC3 cells mediated a fourfold increase in cell death. However, knock-down of XIAP expression enhanced the effect of CSR1 by increasing cell death by an additional 58% (from 43% to 68%, P < 0.001, Figure 2, B and C). Interestingly, expressing BclII using pCMV-BclII did not have a significant impact on CSR1-induced cell death (Table 1), suggesting that CSR1 is a downstream signaling molecule in cell death induction. Treatment of cells with membrane-permeable caspase-9 Inhibitor II, a 16–amino acid peptide that inhibits caspase-9, -4, and -5, reversed cell death induced by CSR1 and siXIAP (Figure 2), suggesting that the CSR1-induced cell death requires caspase activity. Because binding of XIAP with caspase-3, -7, and -9 inhibits the protease activity of these caspases, we then investigated the effect of CSR1 expression on the activity of caspase-9, the initiator of the caspase cascade, in PC3 cells. Induction of CSR1 expression resulted in a 46% increase in caspase-9 activity (P = 0.004). This increase in protease activity was dramatically enhanced (2.8-fold, P < 0.001) when XIAP was down-regulated by siRNA specific for XIAP (Figure 3, A and B). Similarly, the activity of caspase-3 was increased by 48% (P = 0.003) on induction of CSR1. The induction of protease activity was reversed by treatment with a caspase-3–specific inhibitor (Figure 3C), indicating the specificity of the assay. These results suggest that the presence of XIAP prevents the activity of CSR1 in inducing cell death. The binding of CSR1 and XIAP serves to relieve XIAP inhibition of caspase-9 and -3 protease activity.

Figure 2.

Knock-down of XIAP exacerbates cell death induced by CSR1. A: Immunoblots of CSR1 and XIAP expression in WCSR1 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1/pCDNA6) cells treated with or without tetracycline, and then treated with siRNA specific for XIAP (siXIAP), scramble control (Scr), or Caspase-9 Inhibitor II (IC, 1 μg/mL). Cells were harvested for analyses 48 hours after transfection. B: Summary of FACS analysis of annexin V and PI staining of WCSR1 cells transfected with a scrambled siRNA (Scr), XIAP-siRNA (siXIAP), or Caspase-9 Inhibitor II (IC), and treated with or without tetracycline. Triplicate experiments of each condition were averaged in the analyses. *P < 0.001. C: Representative images of FACS analyses from B.

Table 1.

Impact of BCL2 Expression on CSR1-Induced Cell Death

| Cell | Induction | Vector | % Annexin V | % PI | % Annexin V and PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCRS1 | Tet− | pCMVscript | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

| Tet+ | pCMVscript | 32.6 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 21.3 ± 0.7 | |

| Tet− | pCMV-Bcl2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | |

| Tet+ | pCMV-Bcl2 | 35.8 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 21.3 ± 0.8 | |

| WCRS1–2 | Tet− | pCMVscript | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| Tet+ | pCMVscript | 33.4 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 20.7 ± 1.3 | |

| Tet− | pCMV-Bcl2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | |

| Tet+ | pCMV-Bcl2 | 30.2 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 18.7 ± 0.8 |

pCMV, cytomegalovirus plasmid; Tet, tetracycline; WCSR1, PC3 cells transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1/pCDNA6.

Figure 3.

CSR1 activates the protease activity of caspase-9 and -3. A: Immunoblot analysis of CSR1, XIAP and β-actin. WCSR1 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1/pCDNA6) cells were transfected with siXIAP or scramble control (Scr), and treated with or without tetracycline for 48 hours. The cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Similar tetracycline treatment and assays were performed with ΔCSR1-5 cells (pCDNA4-CSR1Δ513–572/pCDNA6 transformed PC3 cells). B: Activation of caspase-9 by CSR1 is dependent on XIAP. WCSR1 or ΔCSR1-5 cells were transfected with siXIAP or Scr and treated with tetracycline to express wild-type or mutant CSR1, respectively, and cell lysates were incubated with caspase-9 substrate (LEHD-pNA). The protease activity of caspase-9 was then quantified in a spectrophotometer. Triplicate experiments of each treatment were analyzed. Reactions without caspase-9 substrate were used as negative controls. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001. C: Activation of caspase-3 by CSR1 is dependent on XIAP. WCSR1 or ΔCSR1-5 cells were transfected with siXIAP or Scr, and treated with tetracycline to express wild-type or mutant CSR1, respectively, and cell lysates were incubated with caspase-3 substrate (DEVD-AFC). The protease activity of caspase-3 was then quantified in a spectrofluorometer. Triplicate experiments of each treatment were analyzed. Reactions without caspase-3 substrate were used as negative controls. The specificity of the assay was evaluated using caspase-3 inhibitor. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

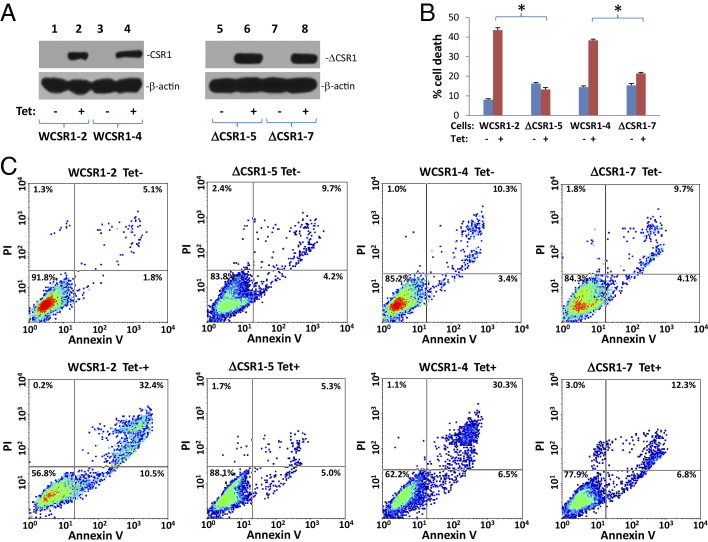

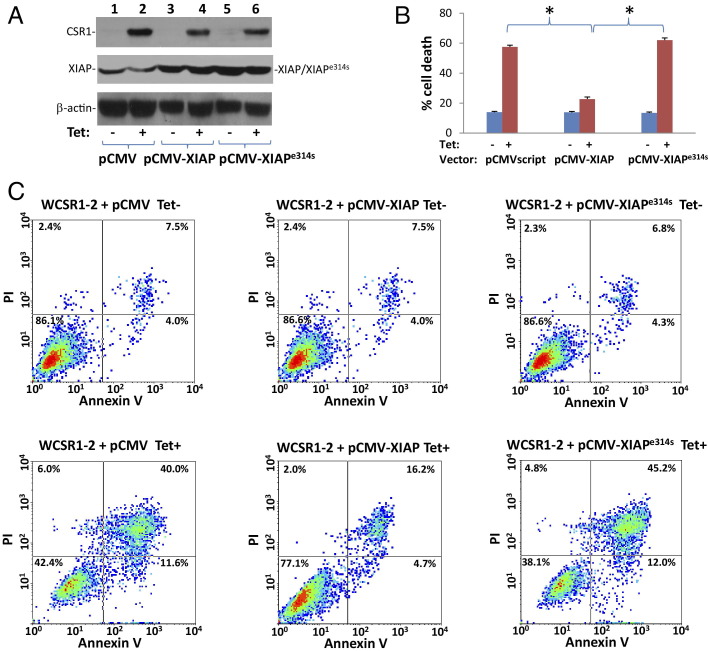

To investigate the role of the CSR1/XIAP interaction in CSR1-induced cell death, a mutant CSR1 that lacks the motif for XIAP binding (CSR1Δ513–572) was created. The mutant CSR1 was then ligated into pCDNA4 to create pCNDA4-ΔCSR1. pCDNA4-ΔCSR1/pCDNA6 were then transfected into PC3 cells to generate a cell line that expresses a mutant CSR1 that does not interact with XIAP on tetracycline treatment. Cell death observed after the induction of mutant CSR1Δ513–572 expression in PC3 cells was greatly reduced compared with cell death mediated by wild-type CSR1 (P < 0.001) (Figure 4, A–C). This result suggests that the XIAP/CSR1 interaction plays an important role in mediating cell death induced by CSR1, probably through inactivation of inhibition activity of XIAP. Indeed, in contrast to wild-type CSR1, induction of CSR1Δ513–572 expression did not increase the protease activity of caspase-9 or -3 (Figure 3, B and C). To rule out the possibility that functions of XIAP other than caspase inhibition were involved in the CSR1-mediated cell death, we generated a point mutation in XIAP (XIAPe314s) that prevents XIAP binding to caspases, and overexpressed it in PC3 cells. If CSR1-induced cell death is mediated by neutralizing the non–caspase inhibition function of XIAP, overexpression of mutant XIAPe314s may antagonize CSR1-induced cell death. However, as shown in Figure 5, our study indicates that overexpression of XIAPe314s had minimal impact on CSR1-induced cell death, whereas the wild-type XIAP reduced CSR1-induced cell death by half (P < 0.001), suggesting that de-inhibition of caspases plays a major role in CSR1-induced cell death.

Figure 4.

Loss of the XIAP-binding motif in CSR1 abrogates CSR1-induced cell death. A: Immunoblots of CSR1 and β-actin expression in WCSR1–2 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1/pCDNA6), WCSR1–4 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1/pCDNA6), ΔCSR1–5 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1Δ513–572/pCDNA6), and ΔCSR1–7 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1Δ513–572/pCDNA6) cells treated with or without tetracycline for 2 days. B: Summary of FACS analysis of cell death in A. Triplicate experiments of each treatment were analyzed. *P < 0.001. C: Representative images of FACS analysis of annexin V and propidium iodide staining of cells in A.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of XIAP antagonizes CSR1-induced cell death. A: Immunoblots of CSR1, XIAP, and β-actin expression in WCSR1–2 (PC3 transformed with pCDNA4-CSR1/pCDNA6) cells transfected with pCMVscript (pCMV), pCMV-XIAP, or pCMV-XIAPe314s treated with or without tetracycline. The cell lysates were then separated by SDS-PAGE and identified with the indicated antibodies. B: Summary of FACS analysis of cell death in A. Triplicate experiments of each treatment were analyzed. *P < 0.001. C: Representative images of FACS analysis of annexin V and propidium iodide staining of cells listed in A.

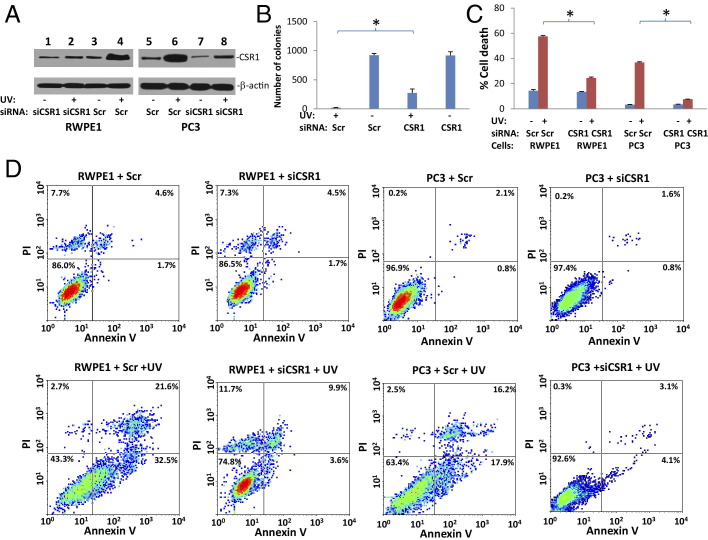

CSR1 is one of the cell stress response proteins that can be induced by UV, X-ray irradiation, or reactive oxygen species.16 To investigate the physiological relevance of CSR1-induced cell death, we investigated RWPE-1 and PC3 cells, in which expression of CSR1 is inducible by UV irradiation (Figure 6A). UV treatment of RWPE1 cells eliminated 98% of colony-forming cells, whereas treatment with CSR1-specific siRNA increased the survival rate to 30% (Figure 6, B and C). Twelve hours after UV irradiation, CSR1 expression was significantly increased in both PC3 and RWPE-1 cells, and cell death was increased by an average of 12-fold (PC3 cells) and fourfold (RWPE-1 cells) (P < 0.001). However, RWPE-1 or PC3 cells in which CSR1 was knocked down experienced significantly less cell death compared with the scramble controls (P < 0.001). These results suggest that CSR1 plays a critical role in UV-induced apoptosis.

Figure 6.

Knock-down of CSR1 partially blocks UV-induced apoptosis. A: Immunoblot analysis of CSR1 and β-actin expressed by cells transfected with siRNA specific for CSR1 (siCSR1) or scramble control (Scr), and treated with or without UV light (16.7 mj/m2). The cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified with the indicated antibodies. B: Colony formation analysis of UV-treated cells. RWPE1 cells (20,000) were treated with or without UV irradiation and siCSR1 or Scr. Colony formations were tabulated 10 days after UV treatment. *P < 0.001. C: Summary of FACS analysis of cell death in A. Triplicate experiments of each treatment were analyzed. *P < 0.001. D: Representative images of FACS analysis of annexin V and propidium iodide staining of cells in A.

Discussion

CSR1 is a membranous scavenger protein known for its role in inducing cell death.7 XIAP is involved in multiple cell functions, including ubiquitin ligation and inhibition of caspases.17,18 XIAP is the only human protein that inhibits caspase activities at both the initiator and effector levels. The present study indicates that CSR1 interacts with and inhibits XIAP both in vivo and in vitro. Several lines of evidence support the conclusion that CSR1 binds with XIAP. First, both full-length CSR1 and the C-terminus of CSR1 bound XIAP in the yeast two-hybrid system and in cell-free in vitro binding assays. The binding of the recombinant CSR1 C-terminus and XIAP in the cell-free system suggests that no bridge protein is involved in the CSR1/XIAP interaction. Second, both CSR1 and XIAP were readily coimmunoprecipitated from prostate epithelial cells by antibodies against either XIAP or CSR1, suggesting the CSR1/XIAP interaction occurs intracellularly. Third, CSR1 and XIAP colocalized in the cytoplasm and at the plasma membrane of the immortalized prostate epithelial cells.

A previous study suggests that CSR1 induces cell death through redistribution of CPSF3 and inactivation of its polyadenylation activity.7 This study indicates that CSR1 inhibits XIAP activity, which would lead to higher levels of caspase-9 and -3 activity on CSR1 expression. Knock-down of XIAP enhanced CSR1-induced cell death. Cells expressing mutant CSR1 that does not bind XIAP experienced significantly less cell death but displayed change in caspase protease activity. These findings suggest that CSR1 can induce cell death by multiple mechanisms. This study also confirms the previous finding that CSR1 expression is induced by cellular stress, such as UV light treatment. Interestingly, CSR1 appears to be a key signaling molecule for UV light–induced cell death, as elimination of CSR1expression by siRNA dramatically attenuated the UV-induced cell death responses. Thus, CSR1-CPSF3 and CSR1-XIAP signaling are critical mechanisms for cellular response to stress.

XIAP belongs to a family of proteins homologous to baculovirus IAP, and is involved in suppression of cell death.19–21 Since its discovery, XIAP has been found to participate in a variety of cellular processes, including ubiquitin ligation, apoptosis, motility, and gene expression regulation.9,12,22–25 The discovery of a XIAP/CSR1 interaction adds a novel function for XIAP as a downstream signaling molecule for a tumor suppressor. The involvement of XIAP in CSR1-induced cell death appears to be critical because a CSR1 mutant lacking the XIAP-binding motif is unable to induce cell death. The motifs for XIAP and CPSF3 do not overlap but are only 30 amino acids apart. The dependency of CSR1 on XIAP to induce cell death raises the possibility that the CSR1-CPSF3-XIAP complex needs to be intact to be functional. It is not clear whether CPSF3 and XIAP interact, however. Alternatively, deletion of the XIAP-binding motif of CSR1 may produce an allosteric effect that adversely affects the function of CSR1. The CSR1 binding domain in XIAP appears in the sequence containing BIR1 which is a different location from the binding sites for caspase-3 and -9. This suggests that CSR1 does not directly compete with caspase-3 or -9 for XIAP binding. Likely, the binding of CSR1 and XIAP generates an allosteric effect or a physical hindrance that interferes with the interaction between XIAP and caspases. A physical structure analysis of CSR1-XIAP complex may shed light on the mechanism of CSR1-mediated XIAP inhibition. Based on the current analysis, CSR1 appears to hijack XIAP from performing its caspase inhibition function.

CSR1 remains an enigmatic protein, the physiological function of which is not fully understood. Low levels of CSR1 expression are found in almost all normal tissues.6 The response of CSR1 to cell stress and its ability to induce cell death might suggest that CSR1 has a function similar to that of a typical tumor suppressor gene such as p53. Even though CSR1 is located in a chromosomal region known to be frequently deleted in a variety of cancers, there is no report suggesting that CSR1 is mutated in cancers. The high frequency of CSR1 methylation observed in prostate cancer samples suggests that epigenetic alteration is the main mechanism for inactivation of CSR1 expression. Because a high level of methylation in CSR1 promoter regions correlates with poor clinical prognosis for patients with prostate cancer, it is possible that restoring the expression of CSR1 in cancer cells could reduce tumor invasiveness, tumor growth, and patient mortality associated with this disease.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA098249 to J.H.L.) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-08-137-01-CNE to Y.P.Y.).

References

- 1.Coon S.W., Savera A.T., Zarbo R.J., Benninger M.S., Chase G.A., Rybicki B.A., Van Dyke D.L. Prognostic implications of loss of heterozygosity at 8p21 and 9p21 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:206–212. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurimoto F., Gemma A., Hosoya Y., Seike M., Takenaka K., Uematsu K., Yoshimura A., Shibuya M., Kudoh S. Unchanged frequency of loss of heterozygosity and size of the deleted region at 8p21-23 during metastasis of lung cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:89–93. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.8.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wistuba I.I., Behrens C., Virmani A.K., Milchgrub S., Syed S., Lam S., Mackay B., Minna J.D., Gazdar A.F. Allelic losses at chromosome 8p21-23 are early and frequent events in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1973–1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohata H., Emi M., Fujiwara Y., Higashino K., Nakagawa K., Futagami R., Tsuchiya E., Nakamura Y. Deletion mapping of the short arm of chromosome 8 in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1993;7:85–88. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870070204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kagan J., Stein J., Babaian R.J., Joe Y.S., Pisters L.L., Glassman A.B., von Eschenbach A.C., Troncoso P. Homozygous deletions at 8p22 and 8p21 in prostate cancer implicate these regions as the sites for candidate tumor suppressor genes. Oncogene. 1995;11:2121–2126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu G., Tseng G.C., Yu Y.P., Gavel T., Nelson J., Wells A., Michalopoulos G., Kokkinakis D., Luo J.H. CSR1 suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:597–607. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Z.H., Yu Y.P., Shi Y.K., Nelson J.B., Luo J.H. CSR1 induces cell death through inactivation of CPSF3. Oncogene. 2009;28:41–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai J., Shiozaki E., Srinivasula S.M., Wu Q., Datta P., Alnemri E.S., Shi Y. Structural basis of caspase-7 inhibition by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104:769–780. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasula S.M., Hegde R., Saleh A., Datta P., Shiozaki E., Chai J., Lee R.A., Robbins P.D., Fernandes-Alnemri T., Shi Y., Alnemri E.S. A conserved XIAP-interaction motif in caspase-9 and Smac/DIABLO regulates caspase activity and apoptosis. Nature. 2001;410:112–116. doi: 10.1038/35065125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silke J., Hawkins C.J., Ekert P.G., Chew J., Day C.L., Pakusch M., Verhagen A.M., Vaux D.L. The anti-apoptotic activity of XIAP is retained upon mutation of both the caspase 3- and caspase 9-interacting sites. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:115–124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki Y., Imai Y., Nakayama H., Takahashi K., Takio K., Takahashi R. A serine protease. HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death, Mol Cell. 2001;8:613–621. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegde R., Srinivasula S.M., Zhang Z., Wassell R., Mukattash R., Cilenti L., DuBois G., Lazebnik Y., Zervos A.S., Fernandes-Alnemri T., Alnemri E.S. Identification of Omi/HtrA2 as a mitochondrial apoptotic serine protease that disrupts inhibitor of apoptosis protein-caspase interaction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:432–438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhagen A.M., Silke J., Ekert P.G., Pakusch M., Kaufmann H., Connolly L.M., Day C.L., Tikoo A., Burke R., Wrobel C., Moritz R.L., Simpson R.J., Vaux D.L. HtrA2 promotes cell death through its serine protease activity and its ability to antagonize inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:445–454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Y.P., Luo J.H. Myopodin-mediated suppression of prostate cancer cell migration involves interaction with zyxin. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7414–7419. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Y.P., Tseng G.C., Luo J.H. Inactivation of myopodin expression associated with prostate cancer relapse. Urology. 2006;68:578–582. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han H.J., Tokino T., Nakamura Y. CSR, a scavenger receptor-like protein with a protective role against cellular damage causedby UV irradiation and oxidative stress. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1039–1046. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashkar H. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis: a chemoresistance factor or a hollow promise. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4496–4502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galban S., Duckett C.S. XIAP as a ubiquitin ligase in cellular signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:54–60. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liston P., Roy N., Tamai K., Lefebvre C., Baird S., Cherton-Horvat G., Farahani R., McLean M., Ikeda J.E., MacKenzie A., Korneluk R.G. Suppression of apoptosis in mammalian cells by NAIP and a related family of IAP genes. Nature. 1996;379:349–353. doi: 10.1038/379349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duckett C.S., Nava V.E., Gedrich R.W., Clem R.J., Van Dongen J.L., Gilfillan M.C., Shiels H., Hardwick J.M., Thompson C.B. A conserved family of cellular genes related to the baculovirus iap gene and encoding apoptosis inhibitors. EMBO J. 1996;15:2685–2694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uren A.G., Pakusch M., Hawkins C.J., Puls K.L., Vaux D.L. Cloning and expression of apoptosis inhibitory protein homologs that function to inhibit apoptosis and/or bind tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4974–4978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seong Y.M., Choi J.Y., Park H.J., Kim K.J., Ahn S.G., Seong G.H., Kim I.K., Kang S., Rhim H. Autocatalytic processing of HtrA2/Omi is essential for induction of caspase-dependent cell death through antagonizing XIAP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37588–37596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shankar S., Chen Q., Siddiqui I., Sarva K., Srivastava R.K. Sensitization of TRAIL-resistant LNCaP cells by resveratrol (3, 4′, 5 tri-hydroxystilbene): molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. J Mol Signal. 2007;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Izeradjene K., Douglas L., Delaney A., Houghton J.A. Influence of casein kinase II in tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6650–6660. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogan T., Harms G.S., Hekman M., Karreman C., Oberoi T.K., Alnemri E.S., Rapp U.R., Rajalingam K. X-linked and cellular IAPs modulate the stability of C-RAF kinase and cell motility. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1447–1455. doi: 10.1038/ncb1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]