Deletion of β-catenin from mouse embryonic endothelium, but not embryonic hematopoietic cells, prevents hematopoietic differentiation; thus Wnt/β-catenin signaling is needed for emergence but not maintenance of HSCs.

Abstract

Understanding how hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are generated and the signals that control this process is a crucial issue for regenerative medicine applications that require in vitro production of HSC. HSCs emerge during embryonic life from an endothelial-like cell population that resides in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region. We show here that β-catenin is nuclear and active in few endothelial nonhematopoietic cells closely associated with the emerging hematopoietic clusters of the embryonic aorta during mouse development. Importantly, Wnt/β-catenin activity is transiently required in the AGM to generate long-term HSCs and to produce hematopoietic cells in vitro from AGM endothelial precursors. Genetic deletion of β-catenin from the embryonic endothelium stage (using VE-cadherin–Cre recombinase), but not from embryonic hematopoietic cells (using Vav1-Cre), precludes progression of mutant cells toward the hematopoietic lineage; however, these mutant cells still contribute to the adult endothelium. Together, those findings indicate that Wnt/β-catenin activity is needed for the emergence but not the maintenance of HSCs in mouse embryos.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are generated during embryonic life from the hemogenic endothelium of specific arterial vessels (Dzierzak and Speck, 2008). Studies in different organisms have demonstrated that the first embryonic site that generates HSCs is the dorsal aorta that is surrounded by the gonad and mesonephros (aorta-gonad-mesonephros [AGM]; Medvinsky and Dzierzak, 1996). More recently, cell-tracing studies have demonstrated that HSCs derive from endothelial-like precursors that express VE-cadherin (VEC; Zovein et al., 2008) as well as Runx1 (Chen et al., 2009). Important progress has been made in the understanding of regulatory signals that govern the emergence of HSCs. Some of the signals required for both adult BM HSCs and embryonic hematopoiesis include the cytokine IL-3 and the transcription factors such as GATA2 and SCL (Robin et al., 2006). However, other signals, including those mediated by the Notch receptor, are specifically required for embryonic hematopoiesis (Kumano et al., 2003; Robert-Moreno et al., 2005, 2008) and not essential for BM HSC (Radtke et al., 1999; Maillard et al., 2008). There is also strong evidence that Notch, Wnt, and BMP pathways collaborate to generate HSC in the zebrafish embryo and also regulate hematopoietic development from embryonic stem cells (ESCs; Burns et al., 2005; Lengerke et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2008; Clements et al., 2011).

Wnt is an important regulator of multiple aspects of embryonic development. However, there is as yet no evidence for its involvement in the onset of hematopoiesis in mammals. The Wnt ligands comprise 19 highly glycosylated secreted proteins that function by associating with the frizzled receptors and the low density lipoprotein receptor protein co-receptors. Upon binding, Wnt signaling triggers different downstream responses dependent on β-catenin (also known as the canonical pathway), JNK, or PKC (also known as noncanonical pathways). Noncanonical pathways do not stabilize β-catenin; rather, they activate G protein complexes and increase Ca+ or Rho/Rac GTPases to activate JNK (Malhotra and Kincade, 2009). The canonical pathway instead is characterized by the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 β (GSK3-β)–dependent phosphorylation of β-catenin, thus blocking its degradation and resulting in its nuclear translocation and activation of β-catenin/TCF-responsive genes. Inhibition of GSK3-β activity is mediated by dishevelled and involves the disruption of a catalytic complex (also known as the destruction complex) formed by Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), casein kinase I, and GSK3-β. Whether Wnt/β-catenin is required for maintaining adult HSCs is controversial; whereas conditional deletion of β-catenin (using Vav1-cre), its inhibition by Dickkopf 1 (DKK1), or Wnt3a deficiency in HSC impairs self-renewal (Reya et al., 2003; Fleming et al., 2008; Luis et al., 2009), inducible deletion of β/γ-catenin genes in BM does not have such effect (Jeannet et al., 2008; Koch et al., 2008). In contrast, ectopic activation of Wnt/β-catenin in vitro enhanced HSC activity, and it was initially interpreted as an effect on HSC expansion (Reya et al., 2003; Goessling et al., 2009). More recently, it has been shown that gain-of-function mutations of β-catenin in vivo result in the exhaustion of this compartment (Kirstetter et al., 2006; Scheller et al., 2006; Renström et al., 2009; Lane et al., 2010). Altogether, this suggests that a delicate balance of the Wnt/β-catenin activity is required to maintain HSC integrity (Malhotra and Kincade, 2009).

Although Wnt has been shown to be important for HSC specification in the zebrafish AGM (Goessling et al., 2009), nothing is known about its role in the generation, amplification, or maintenance of HSCs in the mammalian embryo. To investigate this possibility, we have now extensively characterized different subpopulations of the aorta/AGM endothelium for the activation status of Wnt/β-catenin. We also studied the effect of β-catenin intervention to generate HSCs and show that Wnt/β-catenin activity is transiently required in the AGM to generate long-term HSCs. Finally, we demonstrate that β-catenin is required in the embryonic VEC-expressing cells to contribute to the adult hematopoiesis.

RESULTS

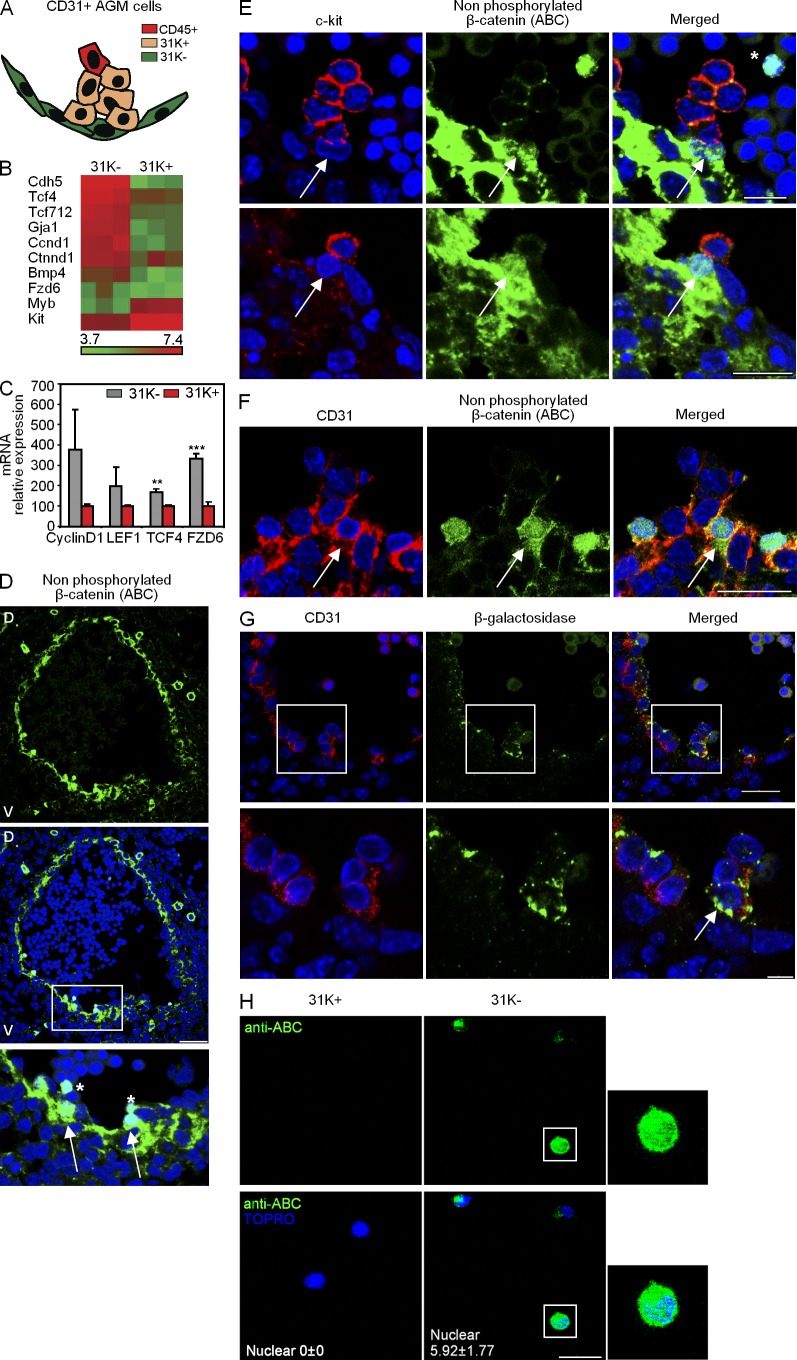

Wnt/β-catenin activity is restricted to few endothelial nonhematopoietic cells in the AGM

The AGM region contains different subtypes of endothelial and hematopoietic precursors at different stages of differentiation toward definitive cells of these lineages. Cells with hematopoietic traits that emerge in clusters from the aorta endothelium can be distinguished from the rest of endothelial cells by the expression of the c-kit receptor (CD117; Yokomizo and Dzierzak, 2010), whereas cells already determined to the hematopoietic lineage, including HSCs, are identified by the expression of CD45. To investigate the mechanisms regulating the endothelial to hematopoietic transition, we compared the expression profile of two endothelial-like cell populations of the AGM based on c-kit expression: 31K− (CD31+c-kit−CD45−) and 31K+ (CD31+c-kit+CD45−; Fig. 1 A). We found that several Wnt family genes were highly enriched in the 31K− population compared with 31K+ (Fig. 1, B and C). Moreover, several Wnt genes, including Wnt3a, are expressed in the endothelium and hematopoietic clusters of E10.5 AGM (unpublished data). Thus, we investigated the activation status of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in nonmanipulated AGMs using the 8E7 antibody, which detects the nonphosphorylated form of β-catenin (directed to Ser37 and Thr41) and recognizes nuclear active β-catenin (ABC; Staal et al., 2002). By immunostaining with this antibody, we found a large accumulation of nonphosphorylated β-catenin in the cytoplasm of most endothelial cells (Fig. 1 D) and in the nucleus of a few cells at the base of the presumptive hematopoietic clusters (Fig. 1 D, detail). By double immunostaining with anti–c-kit antibody, we observed that cells containing nuclear β-catenin were c-kit− but were closely associated with the c-kit+ cells (Fig. 1 E). In addition, these cells express the marker CD31 (Fig. 1 F) and are positive for anti–β-galactosidase staining in the TOPGAL reporter embryos, which is commonly used as readout for Wnt/β-catenin activation (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999; Fig. 1 G). Then, we sorted 31K− and 31K+ cells on slides and performed immunofluorescence with the ABC antibody. We detected nuclear β-catenin in 5.92 ± 1.77% of the 31K− fraction (endothelial), whereas the 31K+ (prehematopoietic) fraction was essentially negative (Fig. 1 H). These results indicate that β-catenin activation occurs in a CD31+ c-kit− and CD45− subpopulation of the aortic endothelium localized at the base of the c-kit+ hematopoietic clusters.

Figure 1.

Wnt/β-catenin activity is restricted to few endothelial nonhematopoietic cells in the AGM. (A) Representation of the surface markers expressed in CD31+ cells to illustrate different endothelial/hematopoietic cell populations present in the AGM region. 31K−, C31+c-kit−CD45−; and 31K+, CD31+c-kit+CD45−. (B) Wnt signature enrichment in the 31K− cells compared with 31K+ in the E11.5 AGM. The heat map represents fold change in differentially expressed genes (P < 0.05). (C) Validation of microarray data by qRT-PCR. Fold change is shown as relative to 31K+ population after normalization by β-actin (n = 2 independent experiments; mean ± SEM). Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (**, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; P > 0.05, unlabeled). (D) Confocal images of a transverse section of E10.5 AGM stained for nonphosphorylated ABC (green), with a detail of nuclear staining in specific endothelial cells (bottom, arrows). Bar, 100 µm. (E) Details of confocal images (E10.5) of hematopoietic clusters with c-kit (red) and ABC (green). Arrows point to nuclear staining at the base of c-kit+ cells. Bars, 25 µm. (F) Detail of confocal images (E10.5) with CD31 (red) and ABC (green). Arrows point to nuclear staining of CD31+ cells. Bar, 25 µm. (G, top) Confocal image of a transversal section of E11.5 AGM from TOPGAL+ embryo stained with anti–β-galactosidase (green) and CD31 (red). Bar, 25 µm. (G, bottom) Arrow points to a CD31+TOPGAL+ cell at the base of a cluster. Bar, 75 µm. (H) Details of confocal images of 31K− or 31K+ sorted from E11.5 AGM cells on slides and immunostained with ABC (green), and a merged image with TOPRO-3 (bottom, blue). Bar, 75 µm. Also shown is a zoom of a cell with nuclear staining (right; n = 3 independent experiments, data shown as mean ± SEM of cell counts of at least five unselected regions with >150 cells counted). Nuclear staining with DAPI is shown in D–G. Asterisks in D and E indicate circulating cells (CD31−c-kit−) with ABC nuclear staining. D, dorsal; V, ventral.

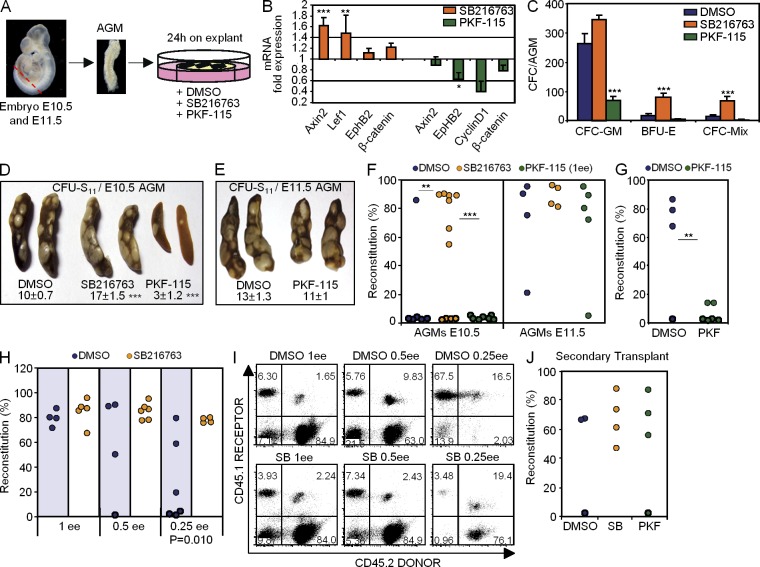

β-Catenin activity is required at embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5) to generate HSCs in the AGM

To functionally evaluate whether β-catenin activity regulates HSC generation in the AGM, we tested the effect of pharmacological inhibitors or activators of the pathway on explant cultures (Fig. 2 A, scheme). This culture system has been extensively used to maintain and amplify the embryonic HSC pool (Medvinsky and Dzierzak, 1996). As a β-catenin activator, we used the GSK3-β inhibitor SB216763 which stabilizes β-catenin at the protein level (Driessens et al., 2010), and as inhibitor we used PKF-115-584 which blocks the interaction between β-catenin and TCF (Lepourcelet et al., 2004). As control, we confirmed that SB216763-treated explants showed increased levels of total and nuclear β-catenin (not depicted) and higher expression of the β-catenin target genes Axin2 and Lef1 (Fig. 2 B), whereas PKF-115 treatment reduced EphB2 and CyclinD1 transcription (Fig. 2 B). We found that β-catenin activation by SB216763 increased the number of colony-forming cells (CFCs) in the explants, which was statistically significant when considering BFU-E (burst-forming unit erythroid) and CFC-Mix colonies. In contrast, β-catenin inhibition led to a reduction of all CFC types, although only CFC-GM (granulo-macrophage CFC) reduction reached statistical significance (Fig. 2 C). We next determined the capacity of these AGM explants to generate colonies in the spleen 11 d after transplantation (CFU-S11) as a measure of the most undifferentiated myeloid progenitors. We found that treating E10.5 AGMs with SB216763 resulted in a twofold increase in the number of CFU-S11, whereas PKF-115 reduced the number of these colonies by threefold (Fig. 2 D). Interestingly, inhibiting β-catenin at E11.5 no longer had any effect in the number of CFU-S11 progenitors (Fig. 2 E), indicating a stage-dependent requirement for β-catenin activity. Finally, we investigated the possible effect of β-catenin modulation in the generation of HSCs by hematopoietic reconstitution of lethally irradiated mice, using single AGM explants untreated or treated with the different compounds. Our results showed that E10.5 AGM cells showed a poor long-term repopulation capacity in the control (one out of six) and PKF-115–treated (zero out of seven) explants (Fig. 2 F, left). However, when animals were transplanted with 2 embryo equivalents (2 ee; 2 AGM explants), we detected hematopoietic reconstitution from the control-treated donor cells in three out of four recipients and HSC activity was essentially lost after PKF-115 treatment (Fig. 1 G). Importantly, single SB216763-treated explants (1 ee) displayed robust engraftment capacity (7 out of 11 animals, P = 0.0029 compared with DMSO control) with a mean contribution of >70% of donor cells in the recipient animal (Fig. 2 F, left). Consistent with the results obtained in the CFU-S11 assays, parallel transplantation experiments using E11.5 AGM explants (1 ee) showed no differences in the repopulation capacity of treated explants compared with the controls (Fig. 2 F, right). However, a more accurate quantification of the HSC activity by limiting dilution experiments (1, 0.5, and 0.25 ee) demonstrated that E11.5 AGMs were still responding to β-catenin modulation because SB216763 treatment significantly increased the reconstitution capacity of the AGM explants when 0.25 ee was transplanted (Fig. 2, H and I). Most importantly, SB216763-treated HSCs preserved their self-renewal capacity as demonstrated by secondary transplants from animals engrafted with E10.5- (not depicted) and E11.5 (Fig. 2 J)-treated AGM explants. On the contrary, AGM and fetal liver (FL) cells from embryos carrying an APC mutation (APCMin/+; Groden et al., 1991) that show constitutive β-catenin activation displayed a marked decrease in the HSC self-renewal capacity in secondary transplants (unpublished data), similar to that reported for APCMin/+ BM cells (Lane et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

β-Catenin activity is required to generate HSCs in the E10.5 AGM. (A) Procedure for AGM explant culture. SB216763 is a GSK3-β inhibitor (β-catenin activator), and PKF-115-584 impairs the binding of β-catenin to TCF (β-catenin inhibitor). (B) qRT-PCR of β-catenin target genes in AGM-treated explants. Results were normalized by β-actin expression and represented as fold increase over the DMSO explant (n = 3 independent experiments, data shown as mean ± SEM). (C) Clonogenic progenitors detected in E10.5 AGMs that were treated as indicated. Clonogenic progenitors were analyzed in methylcellulose cultures. Bars show the mean ± SEM of total hematopoietic progenitors types (CFC-GM, BFU-E, and CFC-Mix; n = 6 AGMs from two independent experiments). (D and E) Spleen images of CFU-S11 obtained from animals transplanted with E10.5 (D) or E11.5 (E) 24-h AGM explant cultures (DMSO n = 12, SB n = 6, and PKF-115 n = 8 for E10.5; DMSO n = 11 and PFK n = 8 for E11.5; n represents the number of AGM/spleen per condition from at least three independent experiments). Zero to two colonies were detected in irradiated noninjected control mice. The mean ± SEM of colonies per tissue is indicated. (F) Transplantation of β-actin−GFP+ E10.5 (left) and E11.5 (right) 24-h AGM-treated explants. Engraftment was measured as the percentage of GFP+ cells within the recipient hematopoietic (CD45+) compartment in peripheral blood (PB) after 16 wk. (G) Engraftment of DMSO-treated or PKF-115–treated E10.5 AGM explants (2 ee) measured in PB 13 wk after transplantation. (H) Quantification of HSC activity by limiting dilution transplantation performed in the CD45.1/CD45.2 system. Engraftment in PB at 16 wk after transplantation of E11.5 AGM explant (1, 0.5, or 0.25 ee) treated with DMSO or SB216763. (I) Dot plot of representative analysis from transplanted animals in H. Single CD45.2+ cells are from the donor AGM, single CD45.1+ cells are from the recipient, and double CD45.1+/CD45.2+ are from spleen cells used as hematopoietic support. (J) Engraftment measured as the percentage of GFP+ cells within the CD45+ compartment in PB at 16 wk after the secondary transplantation of AGM explant at E11.5 from F. (F, G, H, and J) Each dot represents one recipient animal. Data are cumulative of at least three independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; P > 0.05, unlabeled).

Together, these results indicate that HSC generation in the AGM is totally dependent on β-catenin at E10.5, whereas already formed HSCs contained in the E11.5 AGM are β-catenin independent. However, the HSC pool can still be increased by activating β-catenin at this later stage.

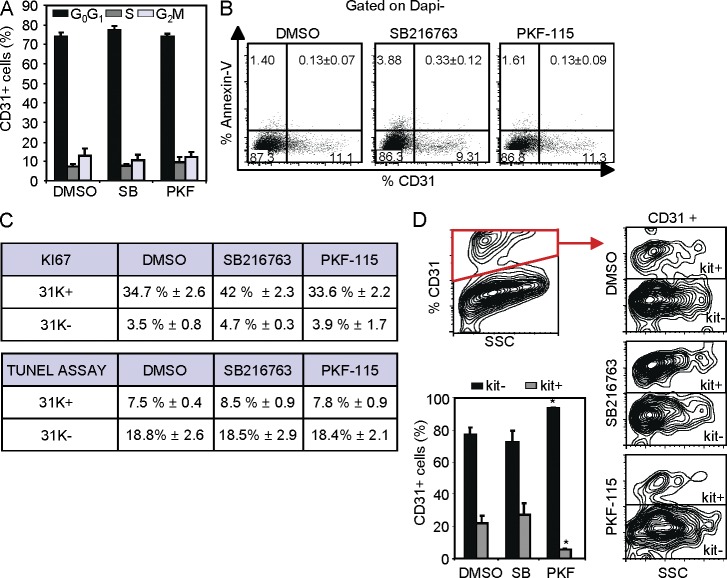

β-Catenin favors hematopoietic differentiation from endothelial precursors

We next investigated the mechanisms underlying the requirement of β-catenin on the generation of HSCs in the AGM. By flow cytometry analysis, we did not detect any change in proliferation or apoptosis (measured by Annexin V binding) in the CD31+ population from different AGM-treated explants (Fig. 3, A and B). Ki67 (proliferation) and TUNEL (apoptosis) staining of sorted 31K+ and 31K− cells confirmed these results (Fig. 3 C, table).

Figure 3.

β-Catenin facilitates hematopoietic differentiation from endothelial precursors. (A and B) Determination of cell cycle by Hoechst staining (A) and apoptosis by Annexin V binding (B) in the CD31+ cells from 24-h AGM explants (E11.5) after the indicated treatments by flow cytometry (n = 3 independent experiments, data shown as mean ± SEM). (C) Mean percentage ± SEM of cells positive for Ki67 staining (top table) and TUNEL assay (bottom table) in the indicated subpopulations. Cells from 24-h-treated E11.5 AGM explants from three independent experiments were directly sorted on slides. Cell counts (>300) from at least five unselected regions have been included. (D) Relative determination of endothelial (c-kit−) and hematopoietic (c-kit+) cells within the CD31+ population in E11.5 24-h AGM-treated explants. Contour plots from a representative experiment. Bars represent percentage of each population (n = 4 independent experiments, data shown as mean ± SEM). Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*, P ≤ 0.05; P > 0.05, unlabeled).

We then analyzed whether Wnt/β-catenin modulators affected the relative percentage of endothelial (CD31+c-kit−) and hematopoietic precursor (CD31+c-kit+) cells in the AGM explants. Our results demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin inactivation significantly decreased the percentage of hematopoietic cells while increasing the endothelial lineage (Fig. 3 D). Conversely, SB216763 treatment resulted in a slight increase in the percentage of hematopoietic precursors (Fig. 3 D), which mimics the effect of the APC mutation in AGM explants (not depicted). These results indicate that β-catenin activity is required to support hematopoietic commitment of the AGM precursors without affecting proliferation or apoptosis of the CD31+ population.

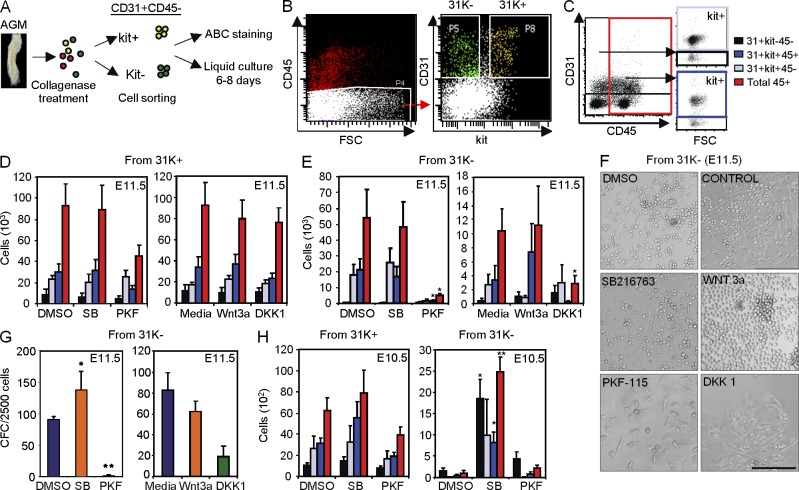

31K− cells produce hematopoietic cells dependent on β-catenin activation

As we found that the 31K− fraction included the cells containing nuclear β-catenin, we directly tested the effects of Wnt modulators on this population compared with the 31K+. With this aim, we performed in vitro cultures of sorted populations using SB216763 or Wnt3a as activators of β-catenin and PKF-115 or DKK1 as β-catenin inhibitors (Fig. 4, A and B; and Fig. S1). We found that untreated or treated 31K+ cells from either E10.5 (Fig. 4 H, left) and E11.5 (Fig. 4 D) produced comparable numbers and percentages of hematopoietic cells as measured by flow cytometry analysis (example in Fig. 4 C) and CFC hematopoietic colony assays (not depicted). Similarly, control or β-catenin–activated (SB216763 and Wnt3a) 31K− cultures from E11.5 AGM produced both adherent and nonadherent round-shaped cells after 8 d of culture (Fig. 4 F) that mostly expressed the CD45 hematopoietic marker (Fig. 4 E), whereas β-catenin activation significantly potentiates the hematopoietic capacity of E10.5 cultures (Fig. 4 H, right). Conversely, inhibition of β-catenin by the pharmacological inhibitor PKF-115 almost abolished the generation of hematopoietic cells from 31K− precursors (Fig. 4, E and F) and the capacity of these cells to form hematopoietic colonies in CFC assays from E11.5 AGMs (Fig. 4 G). Similarly, the use of the recombinant DKK1 inhibitor in these cultures resulted in a decrease in the production of hematopoietic cells, reaching statistical significance when comparing total CD45+ cells (P = 0.043). In contrast, the 31K− population from E10.5 AGM produced very few hematopoietic cells in basal conditions (without exogenous β-catenin activation); thus, the inhibition of the pathway by PKF-115 did not have any effect as expected (Fig. 4 H).

Figure 4.

31K− cells are the target of β-catenin activation to produce hematopoietic cells. (A) Experimental design. (B) Example of sorting windows used to define 31K− and 31K+ subpopulations (see Fig. S1 for purity analysis). (C) Strategy for flow cytometry analysis used in D, E, and H (Endothelial cells: CD31+c-kit−CD45−, black box; prehematopoietic cells: CD31+c-kit+CD45−, gray box; hematopoietic progenitors: CD31+c-kit+CD45+, blue box; total hematopoietic cells: CD45+, red box). (D and E) 1,500 cells from 31K+ (D) and 10,000 cells from 31K− (E) sorted populations were cultured for 6 and 8 d, respectively. Bars show the total number of the indicated cells obtained from 31K+ (D) and 31K− (E) populations (n ≥ 5 independent experiments). (F) Zoom of representative images from 31K− cells after 8 d in liquid culture with the indicated treatments. Bar, 75 µm. (G) Relative number of clonogenic progenitors from 31K− cells after 8 d in culture (n ≥ 7 independent experiments). (H) 1,100 cells from 31K+ and 10,000 cells from 31K− sorted from E10.5 AGMs were cultured as in D and E. Bars show the total number of the indicated cell types obtained from 31K+ (left) and 31K− (right) populations (n ≥ 4 independent experiments). n, number of independent experiments; mean ± SEM. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; P > 0.05, unlabeled). Differences in PKF cultures from 31K+ are nonsignificant compared with SB-treated (p-values are 0.79 [black], 0.64 [gray], 0.12 [blue], and 0.13 [red]) or DMSO-treated (p-values are 0.54 [black], 0.72 [gray], 0.18 [blue], and 0.17 [red]) cultures.

As an additional control, we found that sorted CD31− population (after exclusion of CD45+c-kit+ cells) cultured in the same conditions failed to generate CD45+ hematopoietic cells, even when 30-fold more cells were seeded (unpublished data). Together these results indicate that the 31K− cells contain the hemogenic precursors that depend on Wnt/β-catenin activation to generate hematopoietic cells.

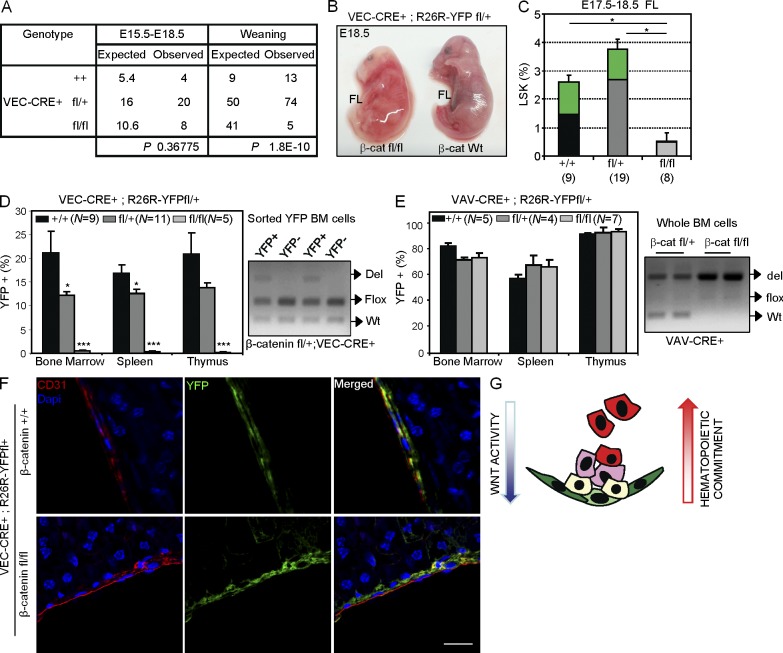

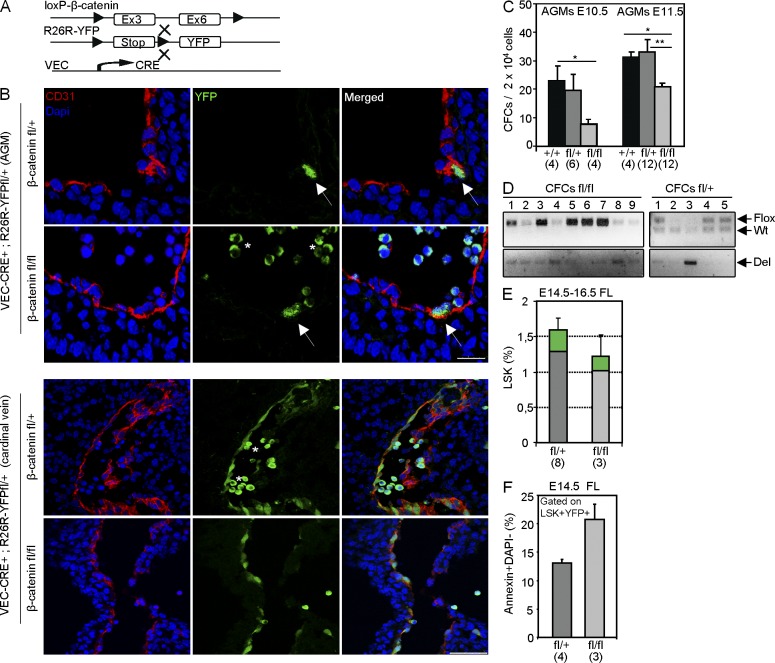

β-Catenin activity in the embryonic endothelium is required to produce adult hematopoietic cells in vivo

Because Wnt/β-catenin–responding cells are contained within the endothelial 31K− population, we further investigated whether deletion of β-catenin in the embryonic endothelium prevented the generation of hematopoietic cells in vivo. We tested this by using a mouse model expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the VEC promoter (VEC-Cre; Zovein et al., 2008) crossed with the R26R fl-stop-fl-YFP mouse to trace Cre activity. Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that VEC-derived YFP-expressing cells are present in the E11.5 AGM (2 ± 0.7% of CD31+ cells) and contribute to the hematopoiesis of E12.5 FL (15.45 ± 2.25% of CD45+ cells; not depicted) and all adult hematopoietic lineages (20.5 ± 3.5% BM; 16.8 ± 1.8 spleen; 20.4 ± 3.4 thymus; see Fig. 6 D and Fig. S2 C). Next, we crossed these mice with the β-catenin floxed line (flanking Exon3 to Exon6; Fig. 5 A) and analyzed the contribution of YFP+ cells to the embryonic and adult hematopoiesis. We detected YFP expression in the endothelium of both heterozygous and homozygous mutant embryos (Fig. 5 B). Determination of functional hematopoietic progenitors by CFC assays in the AGM from the different genotypes demonstrated a strong and significant reduction in the number of progenitors in the β-catenin fl/fl VEC-CRE+ E10.5 and E11.5 AGMs (Fig. 5 C), but not in E11.5 FL (not depicted), compared with the wild-type or heterozygous littermates. Analysis of individual colonies by PCR (Fig. 5 D) showed that the few colonies obtained from the β-catenin fl/fl VEC-CRE+ AGM were generated from cells that failed to efficiently delete the floxed alleles (only 10% of colonies showed a total deletion), suggesting a strong requirement for β-catenin in the developing hematopoietic lineage. In agreement with this, analysis of E14.5 FL showed the presence of some mutant lineage−sca1+c-kit+ (LSK+) YFP+ cells (Fig. 5 E) that displayed increased apoptosis as determined by Annexin V binding (Fig. 5 F). Moreover, analysis of E17.5–18.5 fetuses revealed that most β-catenin fl/fl VEC-CRE+ mutants (seven out of eight) were pale and showed obvious hemorrhages, indicative of both vascular and hematopoietic defects (Fig. 6 B). Importantly, β-catenin–deficient fetuses (E17.5–18.5) have a fivefold reduction in the total FL cellularity, with a threefold reduction in the LSK population and the complete absence of YFP+ cells, as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 6 C). Accordingly, deletion of both β-catenin alleles resulted in perinatal lethality, and only 12% of mutant animals were found at weaning (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S2 A). Moreover, these mutant animals showed no contribution of β-catenin–deleted (YFP+) cells to the adult hematopoiesis (Fig. 6 D and Fig. S2 B), whereas deletion of one β-catenin allele (β-cat fl/+; Fig. 6 D) reduced the percentage of YFP+ cells in the BM and spleen without affecting viability. Similarly, we did not detect any β-catenin–deleted hematopoietic cells in irradiated mice reconstituted with E14.5 FL β-catenin fl/fl VEC-CRE+ cells (unpublished data), which precluded further analysis of β-catenin deletion in HSC. However, YFP+ cells of all genotypes similarly contributed to the adult endothelium of the liver (Fig. 6 F) and kidney (not depicted), suggesting that β-catenin was specifically required for HSC generation after endothelial determination. To study whether β-catenin deletion had any effect in already generated embryonic HSCs, we next induced β-catenin deletion by Vav1-CRE (combined with the YFP floxed allele), which targets hematopoietic cells after the acquisition of CD45 and VEC loss (Chen et al., 2009). We found that deletion of either one or two β-catenin alleles in this mouse model did not affect the contribution of YFP+ cells to the adult hematopoiesis (Fig. 6 E; and Fig. S2, D and E), similar to previously published data (Zhao et al., 2007). Together, our genetic data and the results obtained with pharmacologic modulators of Wnt indicate that β-catenin activity is required in the VEC-expressing cells before the stage of Vav1 expression (around E10–11) to generate HSCs and their progeny in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 6 G, model).

Figure 6.

β-Catenin activity is required in the embryonic endothelium to contribute to adult hematopoiesis. (A) Genotype of progeny from loxP–β-catenin and VEC-Cre intercrosses at different stages (See Fig. S2 A for crossing details). (B) Representative image of affected E18.5 VEC-Cre+;β-catenin Wt or fl/fl fetuses. (C) Percentage of LSK cells in FL at E17.5–18.5 from the different genotypes. Green represents the contribution of YFP+ cells to the LSK population. (D and E) Percentage of YFP+ cells detected in adult hematopoietic organs from VEC-Cre;R26R-YFP;β-catenin +/+, fl/+, or fl/fl (D) or Vav1-Cre;R26R-YFP;β-catenin +/+, fl/+, or fl/fl (E) mice analyzed at 3 mo (left). Analysis of β-catenin allele recombination detected by PCR in the genomic DNA from YFP+ BM sorted cells of VEC-Cre;β-catenin fl/+;R26R-YFP mouse (D, right) and whole BM cells of Vav1-Cre;β-catenin fl/+ or fl/fl;R26R-YFP (E, right). (C–E) Data are shown as mean ± SEM and numbers in brackets indicate the number of mice analyzed. Significant differences compared with control are indicated by asterisks (*, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.001; P > 0.05, unlabeled). (F) Details of confocal images of CD31+ (red) and YFP+ (green) cells in adult liver from β-catenin +/+ or fl/fl mice crossed with VEC-Cre;R26R-YFP analyzed at 3 mo of age. Bar, 75 µm. (G) Model of Wnt/β-catenin activity in the embryonic AGM. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required in the endothelial-like cells to generate hematopoietic progenitors and stem cells but gradually decreases after hematopoietic commitment.

Figure 5.

β-catenin deletion has a deleterious effect on the embryonic hematopoietic progenitors. (A) Conditional deletion of β-catenin in the endothelium. VEC-Cre mice were crossed with R26R-YFP and loxP–β-catenin mice. (B) Detail of confocal image of a transversal section showing endothelium from E10.5 AGM (top) and E11.5 cardinal vein (bottom) from β-catenin fl/+ and β-catenin fl/fl embryos stained for GFP (green) and CD31 (red). Arrows point to CD31+GFP+ cells. Bars, 25 µm. Asterisks indicate autofluorescent circulating cells. (C) Number of CFCs obtained from 2 × 104 AGM cells at E10.5 (left) and E11.5 (right) with the indicated genotypes. (D) Genotype of individual CFC colonies assessed by PCR. Del: deleted band. (E) Percentage of LSK cells in FL at E14.5–16.5 from the different genotypes. Green represents the contribution of YFP+ cells to the LSK population. (F) Percentage of Annexin+Dapi− apoptotic cells within the YFP+ LSK in FL at E14.5 from the different genotypes. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of embryos analyzed in at least three independent experiments. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significant differences compared with control are indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; P > 0.05, unlabeled).

DISCUSSION

To better understand the development of HSCs, we have investigated the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the mouse embryonic aorta in the AGM region at midgestation. The AGM region exhibits activated β-catenin (as well as β-catenin activity) in a small subpopulation of endothelial-like cells. We have demonstrated that embryonic endothelial cells lacking β-catenin activity (by pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion) preclude their contribution to generate HSCs and contribute to the hematopoiesis of the adult organism.

Wnt canonical pathway is important in the maintenance of several types of stem cells such as intestinal, epidermal, or mammary (Reya and Clevers, 2005); however, some questions still remain about the role of β-catenin for the generation and maintenance of HSCs. It has been shown that activation of β-catenin in BM hematopoietic precursors increases the pool of cells with long-term repopulating capacity (Reya et al., 2003; Willert et al., 2003; Goessling et al., 2009) or induces B cells to express HSC markers (Malhotra et al., 2008). Nevertheless, work from different groups has demonstrated that forced β-catenin activity results in the exhaustion of the stem cell compartment by affecting its self-renewal capacity (Kirstetter et al., 2006; Scheller et al., 2006). In addition, impaired β-catenin activation in HSCs (by DKK1 expression [Fleming et al., 2008] or deletion of β-catenin [Zhao et al., 2007] or Wnt3a [Luis et al., 2009]) also has a negative effect on self-renewal. Together these results support a requirement of the just-right dose of β-catenin activity in the HSC compartment (Malhotra and Kincade, 2009; Luis et al., 2011). Instead, our results show that the activity of β-catenin in the embryonic aorta is required in a dose-dependent manner during the generation of HSCs (around E10.5) but not thereafter. Our results are in agreement with previous observations in zebrafish, showing a positive effect of β-catenin activation on HSC formation in the zebrafish AGM through a PKA-dependent mechanism downstream of prostaglandin E2 (Goessling et al., 2009). Although we have not addressed the participation of prostaglandin E2/protein kinase A or other pathways for the activation of β-catenin and requirement for HSC commitment, these observations support the idea that the process is evolutionarily conserved. Deletion of β-catenin by VEC-Cre led to high mortality around birth that is partially a result of the hematopoietic defects but also of the endothelial defects as indicated by the presence of hemorrhages. This phenotype is compatible with that observed for specific endothelial Tie2-Cre–driven β-catenin deletion, although these mutants showed 100% lethality at early E13.5 (Cattelino et al., 2003), which may reflect a higher level of Cre expression.

It was demonstrated that HSCs originate from endothelial precursors expressing VEC during embryonic development (Zovein et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009). However, many questions concerning the biology of this process remain unanswered, such as whether embryonic endothelial-like precursors divide asymmetrically to produce both hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors, or it is a specific population of VEC-positive cells that is already committed to generate the hematopoietic lineage (Rybtsov et al., 2011). We have now demonstrated that a specific CD31 subpopulation lacking c-kit and CD45 expression (called 31K−) generate hematopoietic cells dependent on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Although VEC+CD41+ cells are shown to be the precursors of HSC in the mouse embryos (Rybtsov et al., 2011), we found that total CD31+CD41+CD45− sorted cell population was not affected by Wnt/β-catenin activation when cultured on stromal cells (unpublished data). However, it still remains possible that the CD41+ population inside the 31K− is the one that responds to Wnt/β-catenin.

Understanding the peculiarities that distinguish AGM and BM HSC formation is of crucial importance for future clinical applications, such as generation of hematopoietic cells from ESCs. Several protocols have been successfully developed to produce different cell types and tissues from ESCs but generation of long-term repopulating HSCs have not yet been achieved. Some efforts have been made to elucidate the putative role of Wnt/β-catenin in blood formation from ESCs, and it has been shown that it potentiates flk1+ hemogenic cell formation in both human (Woll et al., 2008) and mouse (Nostro et al., 2008) systems. However, what the effect will be of inducing β-catenin on HSC generation is not totally predictable. In this sense, it was shown that constitutive activation of β-catenin results in deleterious effects on HSC self-renewal (Kirstetter et al., 2006; Scheller et al., 2006; Renström et al., 2009; Lane et al., 2010). Our results demonstrate that transient activation of β-catenin in AGM explants, in contrast to APC mutations, does not impair HSC self-renewal, similar to in vivo inoculation of a GSK3β inhibitor in adult mice (Trowbridge et al., 2006). In summary, β-catenin activity is required in a dose- and time-dependent manner to preserve the functionality of AGM-derived HSCs, which is relevant information for future generation of functional HSCs from ESCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

CD1 or C57Bl6/J (CD45.2) embryos were staged by somite counting: E10.5, 31–40 sp; and E11.5, 42–50 sp. The detection of vaginal plug was designated as 0.5. TOPGAL mice (strain name: STOCK Tg(Fos-LacZ)34Efu/J; DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999), β-actin-GFP mice (strain name: C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP)1Osb/J), R26R-YFP mice (strain name: B6.129X1-GT(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos/J), VEC-Cre mice (strain name: B6.Cg-Tg (Cdh5-cre)7Mlia/J; Alva et al., 2006), and β-catenin fl/fl mice (strain name: Ctnnb1tm2Kem; Brault et al., 2001) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All mice were obtained in the C57B/6J background, except for TOPGAL mice which were bred in the CD1 background. The ratio of inheritance of the β-catenin fl/fl alleles in the VEC-Cre+ background was different from the Mendelian frequency expected. A two-tailed χ2 analysis showed that the observed ratios of +/+ to fl/+ to fl/fl were significantly different from that expected in the adult mice (P < 0.0001). Vav1-CRE mice (CD57B/6J background) have been previously described (Stadtfeld and Graf, 2005). C57B6/J (CD45.2 or CD45.1) mice were used for transplantation experiments. Mice and embryos were all genotyped by PCR or under the UV microscope (GFP lines). Animals were kept under pathogen-free conditions and experimental procedures approved by the Parc de Recerca Biomèdica de Barcelona (PRBB) Animal Care Committee and Government of Catalonia (Decree 214/1997).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Midi C-kit (QIAGEN). RNA quality was assessed on agarose gels and quantified by Nano-Drop1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was obtained with RT First Strand cDNA Synthesis (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate on the Light Cycler 480 (Roche) and with SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for SYBR Green detection are: Axin2 (5′-CCAAGTGTCTCTACCTCATTTTCCG-3′ and 5′-GGTTTGTGGGTCCTCTTCATAGC-3′), c-myc (5′-TATCACCAGCAACAGCAGAGCGAG-3′ and 5′-AACATAGGATGGAGAGCAGAGCCC-3′), LEF1 (5′-CTCATCACCTACAGCGACGA-3′ and 5′-TGAGGCTTCACGTGCATTAG-3′), TCF4 (5′-TTTCGCCTCCTGTAAGCAGT-3′ and 5′-GATTGCCCATATCCATGTCC-3′), GSK3-β (5′-TTCCTTTGGAATCTGCCATC-3′ and 5′-CCAACTGATCCACACCACTG-3′), Ccnd1 (5′-TGACACCAATCTCCTCAACGACC-3′ and 5′-GGATGGCACAATCTCCTTCTGC-3′), EphB2 (5′-TTCTCACCTCAGTTCGCCTCTG-3′ and 5′-CAAACCCCCGTCTGTTACATACG-3′), and β-actin (5′-GTGGGCCGCCCTAGGCACCAG-3′ and 5′-CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′). Expression of individual genes was normalized to β-actin expression.

AGM explant culture.

The AGM region was dissected and cultured as explants for 1–3 d as previously described (Medvinsky and Dzierzak 1996). In brief, AGMs were deposited on nylon filters (Millipore) placed on metallic supports and cultured in myeloid long-term culture medium (Stem Cell Technologies), supplemented with 10 µM hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich), in an air-liquid interphase culture in the presence of DMSO (as a control), 20 µM SB216763 (Sigma-Aldrich), or 0.66 µM PKF-115-584 (Novartis). The explanted AGMs were digested in 0.1% collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS supplemented with 10% FBS for 20 min at 37°C and used for hematopoietic colony assay, qRT-PCR, flow cytometry analysis, or cell transplantation.

Hematopoietic colony assay.

2 × 104 cells from fresh AGMs, 2.5 × 103 cells from FL, 3.5 × 104 cells from AGM explants, or 1.5 × 103 cells from liquid cultures were plated in M-3434 MethoCult medium (STEMCELL Technologies). After 7 d, the presence of hematopoietic colonies was scored under a microscope (CK2; Olympus).

Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting.

Cells were stained for 30 min with different antibodies. Antibodies used were CD31, CD45, and CD117 (c-kit; BD). Ter119 (BD) was used to exclude erythroid cells. DAPI staining (Molecular Probes) or 7-aminoactinomicin-D (7-AAD) staining (Molecular Probes) was used to exclude dead cells. Annexin V (BD) binding was used to determine apoptosis. For cell cycle profile determination, pools of two disrupted AGMs were incubated in 8 µM Hoechst 33342 for 1 h in 10% FBS in PBS at 37°C. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur or LSRII (BD). Cell sorting was performed on a FACSVantage or Aria (BD). Purity of sorted populations was analyzed when enough cells were collected (Fig. S4). All data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Immunofluorescence.

Embryos or tissues were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C, frozen in Tissue-Tek (Sakura), and sectioned (7 µm). Slides were fixed with methanol at −20°C for 15 min and block-permeabilized in 10% FBS, 0.3% Surfact-AmpsX100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 5% nonfat milk in PBS for 90 min at 4°C. Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: anti-nonphosphorylated β-catenin at 1:1,500 (Millipore), anti-CD31 at 1:50 (BD), anti-ckit at 1:50 (BD), anti–β-galactosidase at 1:3,000 (Molecular Probes), and anti-GFP at 1:500 (Takara Bio Inc.) in 10% FBS and 5% nonfat milk in PBS overnight at 4°C. Sections were stained with HRP-conjugated goat anti–rabbit (Dako), HRP-conjugated rabbit anti–rat (Dako), or HRP-conjugated rabbit anti–mouse (Dako) at 1:100 for 90 min and developed using the tyramide amplification system TSA-Plus Cyanine3/Fluorescein System (PerkinElmer). TOPRO-3 or DAPI were used for nuclear staining and mounted in Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories). Cells were counted in five different randomly selected sections.

CFU spleen (CFU-S11).

24-h AGM explants were digested in 0.1% collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS supplemented with 10% FBS for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were injected intravenously into adult lethally irradiated recipients (8.5 Gy). After 11 d, the animals were sacrificed and the presence of macroscopic hematopoietic colonies in the spleen was scored under a stereoscope (KL200 LED; Leica).

AGM liquid culture.

Sorted cells were plated in a MyeloCult (M-5300; STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 10% SCF- and IL-3–conditioned media, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 0.1 ng/µl VEGF, 10 ng/ml IL-6, 10 ng/ml IGF-I, 10 ng/ml FGF-b, 2 U/ml heparin, 50 ng/ml bovine pituitary extract, 4.5 10−4 M monothioglycerol in the presence of DMSO (control), 20 µM SB216763 (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.66 µM PKF-115-584 (Novartis), 0.1 µg/ml Wnt3a (R&D Systems), or 0.1 µg/ml DKK1 (R&D Systems). After 6–8 d in culture, the cells were recovered and analyzed by flow cytometry and colony formation.

Primary and secondary transplantation assays.

Cells were transplanted into adult recipients as previously described (Medvinsky and Dzierzak, 1996). In brief, recipient mice were irradiated at 8.5 Gy γ irradiation (IBL437-C irradiator) and cells were co-injected intravenously with the support of 2 × 105 spleen cells. Unless indicated, all AGM transplantations were performed with cells from one AGM explant and designated as 1 ee. Chimerism was tested at 4 and 16 wk after transplantation as percentage of donor cells (GFP+ or CD45.1/CD45.2). Mice demonstrating ≥5% donor-derived multilineage chimerism after 16 wk were considered reconstituted. For limiting dilution experiments, 0.5 ee (50% of an AGM explant) or 0.25 ee (25% of an AGM explant) was used. In the latter experiments, cells were co-injected with 2 × 105 spleen cells as a support and 2 × 104 BM cells. When animals were sacrificed (after 16 wk), reconstitution was measured in PB and BM. For secondary transplantations, 7 × 106 cells from each primary recipient were intravenously injected. The contribution to the different lineages of the transplanted cells was measured by flow cytometry with specific antibodies: CD3, B220, Ter119, Mac1, and Gr1 (mouse lineage panel; BD).

Microarrays.

CD31+ckit−CD45− and CD31+ckit+CD45− cells were directly sorted on LRT medium from E11.5 AGM from three independent experiments. RNA was obtained and assessed using Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). Microarray expression profiles were obtained using the GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix) and the GCS3000 platform (Affymetrix). After hybridization, the array was washed, stained, and finally scanned to generate CEL files for each array. Data analysis was performed in R (version 2.11.1) with packages aroma.affymetrix, Biobase, Affy, limma, and genefilter. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (version 8.5; Ingenuity Systems) was used to perform functional analysis of the results. A heat map was built using matrix2png (Pavlidis and Noble, 2003). Data is available at GEO (GSE35395).

Statistical analysis.

Student’s t test or parametric analysis of variance was used by applying a rank transformation on the dependent variable. The analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and the level of significance was established at 0.05 (two-sided). P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**) and P < 0.001 (***) has been indicated in the figures or left unlabeled when did not reach significance P > 0.05.

Detection of deleted band from individual colonies by PCR.

Colonies were picked, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 20 µl lysis buffer (0.01 M Tris, pH 7.4, 0.01 M EDTA, pH 8, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.05% SDS). Different dilutions of this mixture were used to assess the deletion. Different combinations of wild-type, floxed, and/or deleted β-catenin alleles were identified by PCR using primers RM41 (5′-AAGGTAGAGTGATGAAAGTTGTT-3′), RM42 (5′-CACCATGTCCTCTGTCTATTC-3′), and RM43 (5′-TACACTATTGAATCACAGGGACTT-3′), resulting in products of 221 bp for the wild-type allele, 324 bp for the floxed allele, and 500 bp for the deleted allele. To confirm the presence of the deleted β-catenin allele, PCR was performed with RM42 and RM43 primers, generating the 500-bp product.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows the purity determination in different fractions of the AGM after cell sorting and Fig. S2 contains a table with Mendelian ratios of expected β-catenin mutant embryos and mice and multilineage contribution of β-catenin WT and mutant cells. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20120225/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Gonzalez and Blanca Luena for technical assistance and all the laboratory members for helpful discussions. Thanks to Andrew McMahon (Roche Institute of Molecular Biology), Berta Alsina and Cristina Pujades (Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona) for critical reagents and Ferran Torres for statistical analysis, Thomas Graf (Center for Genomic Regulation [CRG], Barcelona) for Vav1-Cre mice and for critically reading this manuscript, and Oscar Fornas for Flow Cytometry support (Parc de Recerca Biomèdica de Barcelona [PRBB]). We acknowledge the Confocal Unit (PRBB), the animal facility (PRBB and Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica de Bellvitge [IDIBELL]), and the Microarray facility (Institut Hospital del Mar d'Investigacions Mèdiques [IMIM]). We are grateful to Novartis for providing PKF-115-584.

C. Ruiz-Herguido was a recipient of FPI predoctoral fellowship (SAF2004-03198). L. Espinosa is an investigator of ISCIII program (02/30279). This research was funded by the Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (SAF2007-60080, PLE2009-0111, and SAF2010-15450), AGAUR (2009SGR-23), and Instituto de Salud Carlos III, RTICC (RD06/0020/0098).

There are no competing financial interests to declare.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- ABC

- active β-catenin

- AGM

- aorta-gonad-mesonephros

- APC

- adenomatous polyposis coli

- CFC

- colony-forming cell

- DKK1

- dickkopf 1

- ee

- embryo equivalent

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- FL

- fetal liver

- GSK3-β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3 β

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- LSK

- lineage−sca1+ckit+

- PB

- peripheral blood

- VEC

- VE-cadherin

References

- Alva J.A., Zovein A.C., Monvoisin A., Murphy T., Salazar A., Harvey N.L., Carmeliet P., Iruela-Arispe M.L. 2006. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev. Dyn. 235:759–767 10.1002/dvdy.20643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault V., Moore R., Kutsch S., Ishibashi M., Rowitch D.H., McMahon A.P., Sommer L., Boussadia O., Kemler R. 2001. Inactivation of the beta-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development. 128:1253–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C.E., Traver D., Mayhall E., Shepard J.L., Zon L.I. 2005. Hematopoietic stem cell fate is established by the Notch-Runx pathway. Genes Dev. 19:2331–2342 10.1101/gad.1337005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattelino A., Liebner S., Gallini R., Zanetti A., Balconi G., Corsi A., Bianco P., Wolburg H., Moore R., Oreda B., et al. 2003. The conditional inactivation of the β-catenin gene in endothelial cells causes a defective vascular pattern and increased vascular fragility. J. Cell Biol. 162:1111–1122 10.1083/jcb.200212157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.J., Yokomizo T., Zeigler B.M., Dzierzak E., Speck N.A. 2009. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 457:887–891 10.1038/nature07619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements W.K., Kim A.D., Ong K.G., Moore J.C., Lawson N.D., Traver D. 2011. A somitic Wnt16/Notch pathway specifies haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 474:220–224 10.1038/nature10107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R., Fuchs E. 1999. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 126:4557–4568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessens G., Zheng Y., Gajewski T.F. 2010. Beta-catenin does not regulate memory T cell phenotype. Nat. Med. 16:513–514, author reply :514–515 10.1038/nm0510-513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzierzak E., Speck N.A. 2008. Of lineage and legacy: the development of mammalian hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:129–136 10.1038/ni1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming H.E., Janzen V., Lo Celso C., Guo J., Leahy K.M., Kronenberg H.M., Scadden D.T. 2008. Wnt signaling in the niche enforces hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and is necessary to preserve self-renewal in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2:274–283 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessling W., North T.E., Loewer S., Lord A.M., Lee S., Stoick-Cooper C.L., Weidinger G., Puder M., Daley G.Q., Moon R.T., Zon L.I. 2009. Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration. Cell. 136:1136–1147 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groden J., Thliveris A., Samowitz W., Carlson M., Gelbert L., Albertsen H., Joslyn G., Stevens J., Spirio L., Robertson M., et al. 1991. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 66:589–600 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannet G., Scheller M., Scarpellino L., Duboux S., Gardiol N., Back J., Kuttler F., Malanchi I., Birchmeier W., Leutz A., et al. 2008. Long-term, multilineage hematopoiesis occurs in the combined absence of beta-catenin and gamma-catenin. Blood. 111:142–149 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirstetter P., Anderson K., Porse B.T., Jacobsen S.E., Nerlov C. 2006. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation and multilineage differentiation block. Nat. Immunol. 7:1048–1056 10.1038/ni1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch U., Wilson A., Cobas M., Kemler R., Macdonald H.R., Radtke F. 2008. Simultaneous loss of beta- and gamma-catenin does not perturb hematopoiesis or lymphopoiesis. Blood. 111:160–164 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumano K., Chiba S., Kunisato A., Sata M., Saito T., Nakagami-Yamaguchi E., Yamaguchi T., Masuda S., Shimizu K., Takahashi T., et al. 2003. Notch1 but not Notch2 is essential for generating hematopoietic stem cells from endothelial cells. Immunity. 18:699–711 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane S.W., Sykes S.M., Al-Shahrour F., Shterental S., Paktinat M., Lo Celso C., Jesneck J.L., Ebert B.L., Williams D.A., Gilliland D.G. 2010. The Apc(min) mouse has altered hematopoietic stem cell function and provides a model for MPD/MDS. Blood. 115:3489–3497 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengerke C., Schmitt S., Bowman T.V., Jang I.H., Maouche-Chretien L., McKinney-Freeman S., Davidson A.J., Hammerschmidt M., Rentzsch F., Green J.B., et al. 2008. BMP and Wnt specify hematopoietic fate by activation of the Cdx-Hox pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2:72–82 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepourcelet M., Chen Y.N., France D.S., Wang H., Crews P., Petersen F., Bruseo C., Wood A.W., Shivdasani R.A. 2004. Small-molecule antagonists of the oncogenic Tcf/beta-catenin protein complex. Cancer Cell. 5:91–102 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00334-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis T.C., Weerkamp F., Naber B.A., Baert M.R., de Haas E.F., Nikolic T., Heuvelmans S., De Krijger R.R., van Dongen J.J., Staal F.J. 2009. Wnt3a deficiency irreversibly impairs hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and leads to defects in progenitor cell differentiation. Blood. 113:546–554 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis T.C., Naber B.A., Roozen P.P., Brugman M.H., de Haas E.F., Ghazvini M., Fibbe W.E., van Dongen J.J., Fodde R., Staal F.J. 2011. Canonical wnt signaling regulates hematopoiesis in a dosage-dependent fashion. Cell Stem Cell. 9:345–356 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard I., Koch U., Dumortier A., Shestova O., Xu L., Sai H., Pross S.E., Aster J.C., Bhandoola A., Radtke F., Pear W.S. 2008. Canonical notch signaling is dispensable for the maintenance of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2:356–366 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S., Kincade P.W. 2009. Wnt-related molecules and signaling pathway equilibrium in hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell. 4:27–36 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S., Baba Y., Garrett K.P., Staal F.J., Gerstein R., Kincade P.W. 2008. Contrasting responses of lymphoid progenitors to canonical and noncanonical Wnt signals. J. Immunol. 181:3955–3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvinsky A., Dzierzak E. 1996. Definitive hematopoiesis is autonomously initiated by the AGM region. Cell. 86:897–906 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80165-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nostro M.C., Cheng X., Keller G.M., Gadue P. 2008. Wnt, activin, and BMP signaling regulate distinct stages in the developmental pathway from embryonic stem cells to blood. Cell Stem Cell. 2:60–71 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P., Noble W.S. 2003. Matrix2png: a utility for visualizing matrix data. Bioinformatics. 19:295–296 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke F., Wilson A., Stark G., Bauer M., van Meerwijk J., MacDonald H.R., Aguet M. 1999. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 10:547–558 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renström J., Istvanffy R., Gauthier K., Shimono A., Mages J., Jardon-Alvarez A., Kröger M., Schiemann M., Busch D.H., Esposito I., et al. 2009. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 extrinsically regulates cycling activity and maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 5:157–167 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T., Clevers H. 2005. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 434:843–850 10.1038/nature03319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T., Duncan A.W., Ailles L., Domen J., Scherer D.C., Willert K., Hintz L., Nusse R., Weissman I.L. 2003. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 423:409–414 10.1038/nature01593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Moreno A., Espinosa L., de la Pompa J.L., Bigas A. 2005. RBPjkappa-dependent Notch function regulates Gata2 and is essential for the formation of intra-embryonic hematopoietic cells. Development. 132:1117–1126 10.1242/dev.01660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Moreno A., Guiu J., Ruiz-Herguido C., López M.E., Inglés-Esteve J., Riera L., Tipping A., Enver T., Dzierzak E., Gridley T., et al. 2008. Impaired embryonic haematopoiesis yet normal arterial development in the absence of the Notch ligand Jagged1. EMBO J. 27:1886–1895 10.1038/emboj.2008.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin C., Ottersbach K., Durand C., Peeters M., Vanes L., Tybulewicz V., Dzierzak E. 2006. An unexpected role for IL-3 in the embryonic development of hematopoietic stem cells. Dev. Cell. 11:171–180 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybtsov S., Sobiesiak M., Taoudi S., Souilhol C., Senserrich J., Liakhovitskaia A., Ivanovs A., Frampton J., Zhao S., Medvinsky A. 2011. Hierarchical organization and early hematopoietic specification of the developing HSC lineage in the AGM region. J. Exp. Med. 208:1305–1315 10.1084/jem.20102419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller M., Huelsken J., Rosenbauer F., Taketo M.M., Birchmeier W., Tenen D.G., Leutz A. 2006. Hematopoietic stem cell and multilineage defects generated by constitutive beta-catenin activation. Nat. Immunol. 7:1037–1047 10.1038/ni1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal F.J., Noort Mv M., Strous G.J., Clevers H.C. 2002. Wnt signals are transmitted through N-terminally dephosphorylated beta-catenin. EMBO Rep. 3:63–68 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtfeld M., Graf T. 2005. Assessing the role of hematopoietic plasticity for endothelial and hepatocyte development by non-invasive lineage tracing. Development. 132:203–213 10.1242/dev.01558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge J.J., Xenocostas A., Moon R.T., Bhatia M. 2006. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is an in vivo regulator of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation. Nat. Med. 12:89–98 10.1038/nm1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Fernald A.A., Anastasi J., Le Beau M.M., Qian Z. 2010. Haploinsufficiency of Apc leads to ineffective hematopoiesis. Blood. 115:3481–3488 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K., Brown J.D., Danenberg E., Duncan A.W., Weissman I.L., Reya T., Yates J.R., III, Nusse R. 2003. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 423:448–452 10.1038/nature01611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woll P.S., Morris J.K., Painschab M.S., Marcus R.K., Kohn A.D., Biechele T.L., Moon R.T., Kaufman D.S. 2008. Wnt signaling promotes hematoendothelial cell development from human embryonic stem cells. Blood. 111:122–131 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomizo T., Dzierzak E. 2010. Three-dimensional cartography of hematopoietic clusters in the vasculature of whole mouse embryos. Development. 137:3651–3661 10.1242/dev.051094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Zou J., Ye Z., Hammond H., Chen G., Tokunaga A., Mali P., Li Y.M., Civin C., Gaiano N., Cheng L. 2008. Notch signaling activation in human embryonic stem cells is required for embryonic, but not trophoblastic, lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell. 2:461–471 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Blum J., Chen A., Kwon H.Y., Jung S.H., Cook J.M., Lagoo A., Reya T. 2007. Loss of beta-catenin impairs the renewal of normal and CML stem cells in vivo. Cancer Cell. 12:528–541 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zovein A.C., Hofmann J.J., Lynch M., French W.J., Turlo K.A., Yang Y., Becker M.S., Zanetta L., Dejana E., Gasson J.C., et al. 2008. Fate tracing reveals the endothelial origin of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 3:625–636 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.