Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine if bed delivery without stirrups reduces the incidence of perineal lacerations compared to delivery in stirrups.

STUDY DESIGN

In this randomized trial we compared bed delivery without stirrups to delivery in stirrups in nulliparous women. The primary outcome was any perineal laceration (first- through fourth-degree).

RESULTS

108 women were randomized to delivery without stirrups and 106 to stirrups. A total of 82 (76%) women randomized to no stirrups sustained perineal lacerations compared to 83 (78%) in women allocated to stirrups, p = .8. There was no significant difference in the severity of lacerations or in obstetric outcomes such as prolonged second stage of labor, forceps delivery, or cesarean birth. Similarly, infant outcomes were unaffected.

CONCLUSION

Our results do not incriminate stirrups as a cause of perineal lacerations. Alternatively, our findings of no difference in perineal lacerations suggest that delivering in bed without stirrups confers no advantages nor disadvantages.

Keywords: delivery position, delivery posture, stirrups, bed delivery

INTRODUCTION

The rate of cesarean delivery in the United States reached its highest point in history in 2009. Indeed, between 1996 and 2009, the cesarean rate increased from 20.7% to 32.9%, which is almost a 60% increase in a 14-year period.1 One of the many factors thought to contribute to this rise is fear of pelvic floor dysfunction manifest as urinary or fecal incontinence following vaginal delivery. Indeed, severe perineal lacerations sustained during vaginal birth are powerful markers for pelvic floor dysfunction, especially anal incontinence.2–6 Perineal lacerations are classified, in order of increasing severity, from first- through fourth-degree.7 Despite diagnosis and repair of third and fourth-degree (anal sphincter) lacerations at the time of delivery, up to half of women who sustain these lacerations report some degree of anal incontinence 3 to 6 months postpartum.8–12 Moreover, anal sphincter lacerations have become an obstetric quality indicator currently in use by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and have been adopted by The Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) as a core performance measure for “pregnancy and related conditions”.13

In 1920, Joseph DeLee14 proposed routine use of prophylactic forceps and episiotomy for all nulliparous women in order to protect the pelvic floor. This seemingly paradoxical use of forceps and episiotomy as preventive procedures was widely adopted and became part of conventional obstetric practice for most of the 20th century.15 This practice however had consequences. For example, in a prospective observational trial of more than 10,000 nulliparous women, episiotomy and forceps delivery were independent risk factors for anal sphincter lacerations.16 A consequence of DeLee’s approach has been that most women today routinely deliver in stirrups. We hypothesize that forced thigh abduction when the legs are positioned in stirrups is greater than when such stirrups are not used and the woman is allowed to flex their legs at the knees and choose a comfortable abduction for delivery of the infant. We further hypothesized that the soft tissues of the perineum are stretched during delivery of the infant and that this stretch may be greater when stirrups are used leading to lacerations of the perineum. Thus, we hypothesized that the rate of any perineal laceration, to include lacerations not involving the anal sphincter, would be reduced by a simple change in common obstetric practice, i.e., delivery without stirrups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY PATIENTS

In this randomized trial, we enrolled nulliparous women ≥16 years old presenting in spontaneous active labor at ≥ 370/7 weeks gestation and with singleton fetuses in cephalic presentation. Only nulliparous women were included because they have the highest rates of perineal lacerations. Exclusion criteria included any obstetric or medical complication of pregnancy, 8 cm or greater cervical dilatation, and prior history of perineal trauma requiring surgical repair or known congenital perineal malformation. Women with any obstetric or medical complication of pregnancy, such as pregnancy related hypertension, diabetes, and labor induction were excluded as these women have higher rates of cesarean delivery. Women with prior history of perineal trauma requiring surgical repair or known congenital perineal malformation were excluded because these women have potential for higher risk of birth related perineal lacerations. Women with cervical dilatation ≥ 8 cm were excluded because advanced labor might obviate obtaining informed consent. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

STUDY PROCEDURES

This trial took place in one of three labor and delivery units at Parkland Hospital. This unit, Labor and Delivery East, is staffed by certified nurse midwives supervised by one on-duty faculty obstetrician-gynecologist as well as one fourth year and one second year house officer in obstetrics and gynecology. Labor and delivery practices in this unit are specified in a written protocol. Women admitted to Labor and Delivery East are limited to those with term singleton pregnancies.

Eligible women were enrolled by attending Labor and Delivery East certified nurse midwives. Until the beginning of the second stage of labor, management of women consenting to this study was similar. Cervical examinations are routinely performed at 2–3 hour intervals during labor. Fetal monitoring was done according to the standard practice of intermittent use of Doppler devices to evaluate the fetal heart rate with continuous electronic fetal monitoring used when abnormalities were heard. Epidural analgesia was available. Routine episiotomy is not practiced at our institution.

Randomization occurred when the attending midwife ascertained cervical dilatation was complete (10 cm). At that time, consecutively numbered opaque randomization envelopes were opened by the Labor and Delivery East Unit clerk and the attending midwife was notified of the randomization assignment. To determine the intervention assignment we used permuted block randomization in block sizes of 4, 6, and 8. This randomization sequence was computer generated by one of the investigators (DDM). Block randomization was used to maintain similar number of women in each intervention assignment and different block sizes were used in attempts to minimize guessing of the randomization assignment. Women were allocated to bed delivery without stirrups or to delivery in stirrups (Figure 1). Women randomized to delivery in stirrups were placed in the stirrups once the fetal head visibly distended the vulva. Women who delivered in a position other than the one assigned by randomization and those who required forceps or cesarean delivery after randomization were analyzed using the intention-to-treat principle.

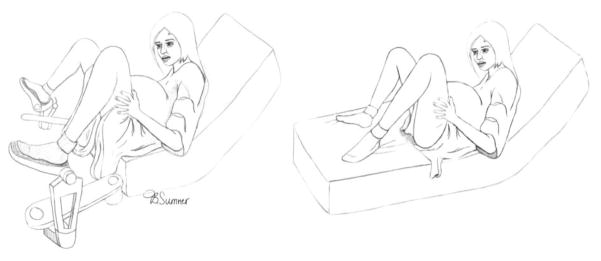

Figure 1.

Delivery positions randomly allocated when the fetal head visibly distended the vulva. Shown are an artist’s rendition made from photographs taken prior to the study. A. shows delivery with stirrups and B. delivery position without stirrups.

All the midwives staffing the Parkland Labor and Delivery East Unit underwent training and certification in the study procedures for this trial. This included didactic presentation concerning the details of the study protocol and study forms. Also included was a video review of perineal anatomy and classification of perineal lacerations as well as repair.17,18

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The primary outcome was any perineal laceration graded as defined in the 23rd Edition of Williams Obstetrics7 and summarized in Figure 2. In each patient, the specific degree of perineal laceration was determined following delivery of the infant and placenta. Perineal lacerations were graded from first- through fourth-degree and annotated in a non-study perineal laceration form routinely completed at each vaginal birth as part of our obstetric practice. This primary outcome was chosen due to sample size considerations. For example, if we had used anal sphincter laceration as the primary outcome measure, the required sample size was 3726 to achieve 80% power to detect one-third reduction in such lacerations, given our observed rate of 6% in a similar population delivered at our hospital. Given this reality, we opted to perform a trial of any perineal laceration as a prelude to a possible subsequent multicenter trial using anal sphincter lacerations as the primary outcome.

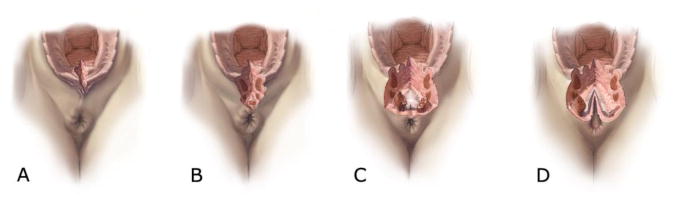

Figure 2.

Classification of perineal lacerations. A. First-degree laceration: superficial tear that involves the vaginal mucosa and/or perineal skin; B. Second-degree: tear extends into the muscles that surround the vagina; C. Third-degree: tear extends into the striated anal sphincter muscle; D. Fourth-degree: tear extends into the anorectal lumen.

In order to increase precision of the description of perineal lacerations and minimize bias, one of the team leader midwives independently recorded a second perineal examination. The annotations made by the independent examiners were used in analysis of results.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The rate of the primary outcome (any perineal laceration) at Parkland Hospital in 2007 was 60% in women potentially eligible for this study. Given a perineal laceration rate of 60%, 194 women randomized to two arms (97 in each arm) provided 80% power to detect an absolute 20% difference in perineal laceration rate, i.e., 60% to 40%. This 60% to 40% change represented a one-third relative reduction in any perineal laceration. The sample size was increased to 214 total women to take into account attrition due to cesarean deliveries occurring after randomization.

Other outcomes included for analysis, such as anal sphincter lacerations and variables potentially implicated to be risk factors for any perineal laceration were also analyzed. Included were 1) augmentation of labor with oxytocin, 2) episiotomy, 3) epidural analgesia, 4) prolonged second stage of labor (2 or 3 hours depending on epidural use), 5) occiput posterior fetal head position at delivery, and 6) birthweight >4000g.

The proportion of women with any perineal laceration in the bed delivery group was compared with the proportion in the stirrups delivery group using the Chi-square test. Adjustment for significant demographic variables was accomplished using Logistic regression. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of continuous measures.

RESULTS

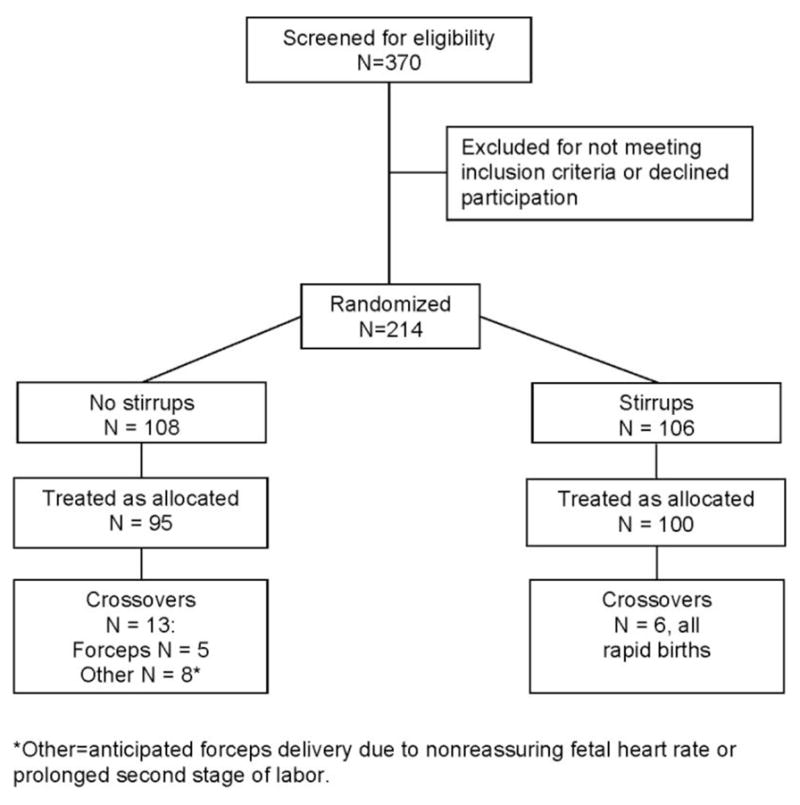

Shown in Figure 3 is the flow diagram of women screened and enrolled in this trial. Between March and December, 2009 a total of 214 women were randomized and 202 (94%) delivered vaginally. 108 women were randomized to no stirrups and 106 were randomized to stirrups. As shown in Table 1, the race/ethnicity distribution of the study participants was significantly different between the two study groups. White women were over represented in the no stirrups group. There were no differences in maternal age or body mass index.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of women enrolled in this trial.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics in 214 nulliparous women randomized to delivery in bed (no stirrups) versus delivery in stirrups.

| No stirrups N = 108 |

Stirrups N = 106 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 22.2 ± 5.2 | 22.0 ± 4.9 | 0.80 |

| Race/ethnicity: | 0.008 | ||

| Hispanic | 94 (87) | 95 (90) | |

| White | 12 (11) | 2 (2) | |

| African-American | 2 (2) | 7 (6) | |

| Asian | 0 | 2 (2) | |

| BMI* | 29.7 ± 4.4 | 29.1 ± 4.4 | 0.38 |

All data shown as N (%) or mean ± SD.

BMI = body mass index (kg/m2).

Although this study was not powered to detect differences in secondary outcome variables, obstetric characteristics that might impact perineal lacerations for the two study groups are compared in Table 2 and there were no differences. Similarly there were no significant differences in infant outcome related to birth with or without stirrups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Obstetric characteristics in 108 women randomized to no stirrups compared to 106 women randomized to delivery in stirrups.

| No stirrups N = 108 |

Stirrups N = 106 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Episiotomy | 5 (5) | 7 (7) | 0.53 |

| Epidural analgesia | 87 (81) | 79 (75) | 0.29 |

| Oxytocin augmentation of labor | 61 (56) | 50 (47) | 0.17 |

| Occiput posterior fetal head | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 0.78 |

| Prolonged second stage of labor* | 8 (7) | 10 (9) | 0.59 |

| Forceps delivery | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 0.98 |

| Cesarean delivery | 6 (6) | 6 (6) | 0.97 |

All data shown N (%).

Prolonged second stage of labor = ≥ 2 hours or ≥ 3 hours if epidural analgesia.

Table 3.

Selected infant outcomes in relation to mode of delivery.

| No stirrups N = 108 |

Stirrups N = 106 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Apgar scores: | |||

| 1-minute ≤ 3 | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 0.09 |

| 5-minure ≤ 3 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Umbilical artery blood pH < 7.1 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.57 |

| Birthweight > 4000g | 3 (3) | 5 (5) | 0.45 |

| Admission to intensive care | 0 | 0 | NA |

All data shown as N (%).

A total of 82 (76%) women randomized to no stirrups sustained one or more perineal lacerations compared to 83 (78%) of those allocated to stirrups, p = 0.8. A total of 145 various perineal lacerations were recorded in each study group. Shown in Table 4 is the comparison of perineal lacerations in women delivered without stirrups compared to birthing with stirrups. There were no significant differences in the severity of perineal lacerations and there were no significant differences when combinations of lacerations were analyzed. Results in Table 4 were then adjusted for maternal race and ethnicity using logistic regression and stirrups use was not significantly associated with lacerations. In addition, an as-treated analysis was done comparing 101 women treated without stirrups to 113 treated with stirrups (see Figure 3) and the rates of perineal lacerations were 74% and 80%, respectively, p = .35.

Table 4.

Perineal lacerations in women randomized to delivery using stirrups versus delivery without stirrups.

|

No Stirrups N = 108 |

Stirrups N = 106 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Worst recorded laceration: | |||

| None | 26 (24) | 23 (22) | 0.80 |

| First-degree | 33 (31) | 31 (29) | |

| Second-degree | 44 (41) | 46 (44) | |

| Third-degree | 4 (4) | 6 (6) | |

| Fourth-degree | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| One or more lacerations | 82 (76) | 83 (78) | 0.80 |

| Two or more lacerations | 49 (45) | 52 (49) | 0.59 |

All data shown as N (%).

COMMENT

Our hypothesis, that birthing in stirrups was associated with increased perineal lacerations was not born out. That is, our results do not incriminate use of stirrups as a cause of perineal lacerations. Alternatively, our findings of no difference in perineal suggests that delivery in bed without stirrups confers no advantages and, perhaps equally importantly, no disadvantages with respect to this outcome.

Risk factors for perineal lacerations at childbirth may be divided into maternal, fetal, and obstetric causes.19 Nulliparity, episiotomy, forceps delivery, and excessive fetal weight are some of the factors implicated in perineal lacerations at delivery. In contrast, there has been much less focus on the potential importance of maternal delivery postures vis-à-vis perineal injuries during childbirth. Gupta, Hofmeyr and Smyth recently performed a Cochrane review on the effects of maternal position in the second stage of labor.20 Included were the effects of several maternal positions on perineal lacerations. A total of 11 reports were identified that address perineal lacerations related to maternal position. Studied maternal positions included supine, dorsal lithotomy, lateral recumbent (Sims position), sitting, squatting, and kneeling. Generally, second degree perineal lacerations were reduced significantly in the supine/lithotomy position compared to any of the other postures. However, no maternal position had any effect on the rate of anal sphincter lacerations. We were unable to find any reports that specifically parallel our study of stirrups, compared to delivery in bed without stirrups.

In the conceptualization of this trial, we preferred to study the effects of stirrups/no stirrups on anal sphincter lacerations as this outcome seemed more meaningful than less severe perineal lacerations. Sample size considerations precluded using anal sphincter lacerations unless a large multicenter trial was performed. We concluded that a lesser trial using any perineal laceration as the primary outcome might provide useful baseline insights as a prelude to a much larger trial using anal sphincter lacerations as the outcome of interest. Although the trial now reported cannot address anal sphincter lacerations, we are of the view that this trial has provided results that can be used to justify a larger trial of stirrups/no stirrups.

We recognize that the rate of the primary outcome (any perineal laceration) was higher than the rate used for sample size calculation. We attribute this to the fact that our observations were taken under controlled experimental conditions. We also noted that white women were over represented in the no stirrups group. Although randomization should provide balance between groups, it is not a guarantee. As the randomization assignment was blinded there was no opportunity for selection bias. The experiments were completely removed from the treatment assignment process.

Given that in 2007, 91.4% of the more than 4 million livebirths in the United States were hospital births attended by physicians, it is likely that stirrups were used in a majority of these births.21 It might therefore be argued based on our results, if there are no disadvantages to birthing without stirrups and no advantages for routine use of stirrups, why use stirrups? We are of the view that there are continuing indications for stirrups such as operative vaginal delivery or for adequate examination of the perineum and vaginal walls when there is hemorrhage or laceration. In the absence of such indications routine use of stirrups is probably unnecessary in the great majority of births where such stirrups are now commonly used.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: NIH CTSA Grant UL1 RR024982

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest

This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov under Registration # NCT00895973

No reprints will be available

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National vital statistics report. 3. Vol. 59. National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. Births: Preliminary data for 2009 [online] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford LA, Quint EH, Pearl ML, DeLancey JOL. Incontinence following rupture of the anal sphincter during delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:527–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1905–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handa VL, Danielsen BH, Gilbert WM. Obstetric anal sphincter lacerations. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(2):225–30. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01445-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO. Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Zyczynski H, Fitzgerald MP, Whitehead W, et al. Fecal and urinary incontinence in primiparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:863–72. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000232504.32589.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY. Williams Obstetrics. Normal Labor and Delivery. (23) 2010;Chapter 17:400. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haadem K, Ohrlander S, Lingman G. Long-term ailments due to anal sphincter rupture caused by delivery: a hidden problem. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1988;27:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0028-2243(88)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haadem K, Dahlstrom JA, Lingman G. Anal sphincter function after delivery: a prospective study in women with sphincter rupture and controls. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:7–13. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(90)90136-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Bartram CI. Third degree obstetric anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome of primary repair. BMJ. 1994;308(6933):887–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6933.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;183:1220–4. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zetterstrom J, Lopez A, Holmstrom B, Nilsson BY, Tisell A, Anzen B, et al. Obstetric sphincter tears and anal incontinence: an observational follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:921–8. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2003.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AHRQ quality indicators. AHRQ Pub; no 03-R203. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2007. Mar 12, Guide to patient safety indicators [version 3.1] p. 76. Available at http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLee JB. The prophylactic forceps operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1920;1:34–44. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabbe SG. The prophylactic forceps operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:254–5. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey BM, Schaffer JI, Bloom SL, Heartwell SF, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Obstetric antecedents for postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1655–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roshanravan SR, Pietz JT, Chao TT, Corton MM. Fourth Degree Obstetric Lacerations: Anatomy and Repair. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2008. [Accessed November, 2009]. Available at: http://www.acog.org/bookstore/Fourth_Degree_Obstetric_Lace_P608C85.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao TT, Wendel GD, Jr, McIntire DD, Corton MM. Effectiveness of an instructional DVD on third- and fourth-degree laceration repair for obstetrics and gynecology postgraduate trainees. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109(1):16–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman D, Ragnar I, Ekström A, Tydén T, Olsson SE. Anal sphincter lacerations and upright delivery postures--a risk analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007 Feb;18(2):141–6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0123-9. Epub 2006 Apr 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta JK, Hofmeyr GJ, Smyth R. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(4):Art. No.: CD002006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002006.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura MA, Matthews TJ, Kirmeyer S, Osterman MJ. Births: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]