Abstract

Objective

To describe characteristics of patients seeking medical attention for non-urgent conditions at an emergency department (ED) and patients who use non-scheduled services in primary healthcare.

Design

Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Setting

Primary healthcare centres and an ED with the same catchment area in Stockholm, Sweden.

Patients

Non-scheduled primary care patients and non-referred non-urgent ED patients within a defined catchment area investigated by structured face-to-face interviews in office hours during a nine-week period.

Main outcome measures

Sociodemographic characteristics, chief complaints, previous healthcare use, perception of symptoms, and duration of symptoms before seeking care.

Results

Of 924 eligible patients, 736 (80%) agreed to participate, 194 at the ED and 542 at nine corresponding primary care centres. The two groups shared demographic characteristics except gender. A majority (47%) of the patients at the primary care centres had respiratory symptoms, whereas most ED patients (52%) had digestive, musculoskeletal, or traumatic symptoms. Compared with primary care patients, a higher proportion (35%) of the ED patients had been hospitalized previously. ED patients were also more anxious about and disturbed by their symptoms and had had a shorter duration of symptoms. Both groups had previously used healthcare frequently.

Conclusions

Symptoms, previous hospitalization and current perception of symptoms seemed to be the main factors discriminating between patients studied at the different sites. There were no substantial sociodemographic differences between the primary care centre patients and the ED patients.

Keywords: Adult, attitude to health, community medicine, cross-sectional, emergency service/hospital, family practice, healthcare surveys, triage

Current knowledge about non-urgent patients attending emergency departments (EDs) is mostly based on studies conducted during the 1990s. This study showed that:

Non-urgent ED patients suffered from other symptoms compared with patients in primary care.

Non-urgent ED patients had had shorter symptom duration prior to the visit and had been hospitalized more often previously.

No major differences regarding sociodemographic characteristics between patients attending EDs and primary care were found except for gender.

Healthcare providers and researchers both in Europe and in the USA have claimed for several decades that up to 55% of the attendances at emergency departments (ED) are made for non-urgent complaints that are more suitable for primary care[1], [2]. This has been associated with a low socioeconomic standard, low education, and young age [1], [3–5]. In most previous studies however, non-urgent patients have been compared with urgent patients at an ED, but not with primary care patients [5–8].

Since there has been a substantial reduction in the number of hospital beds and cut-backs in the number of 24-hour casualty departments in recent years, considerable resources have been devoted to gate-keeping and redirection of non-urgent patients to primary care. However, there is a lack of studies addressing the extent to which the structural changes have had the desired effect, compared with the situation during the 1990s.

This study was conducted to shed further light on the question of whether patients attending primary care on a relatively urgent basis differ from ED patients with a similar level of urgency (ED triage level four), rather than to determine how ED patients with such non-urgent complaints differ from those who come to the ED with urgent conditions. Some reports on this issue have been published previously, but those studies were small [9], based on old data [10–12], or mainly focused on services in out-of-office hours [13], [14].

In this study an attempt was made to identify any differences in demographic characteristics, past medical history, chief complaints, and perception and duration of symptoms prior to the visit between patients seeking medical attention for non-urgent conditions at an ED and patients using non-scheduled services in primary care.

Material and methods

Study design

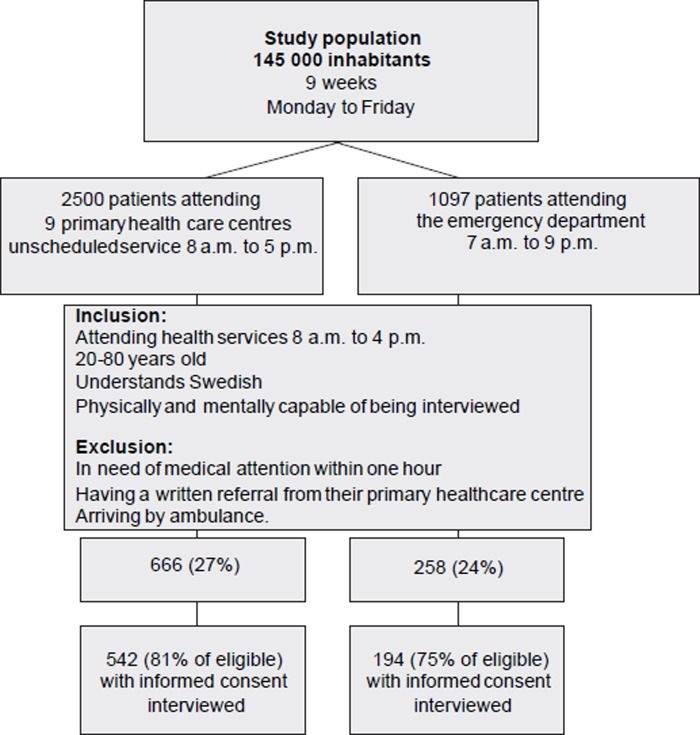

This was a cross-sectional interview-based study on patients from a defined catchment area (Figure 1).

Figure 1. .

Flow chart of the study patients.

Setting

Healthcare delivery in Sweden is organized by county councils and all residents are covered by the national health insurance system, which is primarily financed by taxes. Primary care is provided in healthcare centres, each serving the population of a defined geographical catchment area. There are about 200 primary healthcare centres in the county of Stockholm, which has a population of 1.9 million inhabitants. These centres are staffed by general practitioners, and provide medical service mainly during office hours.

Stockholm Söder Hospital is a public general hospital with 505 beds and with a catchment population of about 500 000. The ED of this hospital, which was the focus of this study, has an average of 90 000 visits per year by patients aged 15 years and older. During the study period physicians representing internal medicine, cardiology, surgery, obstetrics, and orthopaedics were on call at the ED around the clock. Forty primary healthcare centres are located within the same catchment area. All centres are reimbursed by the tax-financed county council and have the same responsibilities irrespective of whether they are publicly or privately owned. A patient with an urgent symptom, or who has met with an accident, may choose to contact his or her primary healthcare centre, but may also attend a hospital ED without referral. Among the inhabitants of the county of Stockholm, 3.9 visits per person and year were made to a physician in primary or specialized care, of which, about 0.12–0.20 were unscheduled visits to primary care or EDs [15], [16].

Co-payment

The patient co-payment per visit in 2002 was set at US$ 20 at the primary care centres and US$ 38 at the EDs. There was also a high-cost ceiling, unrelated to the patient's income. A patient who had paid a total of US$ 160 in patient fees was entitled to free medical care for the rest of the 12-month period, calculated from the date of the first consultation. During the year 2002, 12% of the population was entitled to such a “free care card” in the county of Stockholm [17].

Participants

Of the above mentioned 40 primary healthcare centres, patients from nine randomly selected centres, each with a catchment population of more than 9000, were enrolled in the study after agreeing to participate. The final catchment area covered 145 000 inhabitants out of the 500 000 inhabitants in the catchment area of Stockholm Söder Hospital and represented both urban and rural municipalities and suburbs in the southern and central parts of Stockholm.

At the ED a four-level scale based on the patients’ vital signs was used for triage. Level one demands immediate medical attention, level two attention within 30 minutes, level three attention within one hour, and level four attention after one hour. At the primary care centres, the level of urgency was assessed through telephone contact with a nurse or a general practitioner before the visit or directly at the visit.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients had to have contacted one of the nine primary healthcare centres and received an appointment within the following 24 hours, or to have gone directly to the ED without a written referral from a general practitioner in the catchment area. At the ED only patients living in the catchment areas of the nine primary care centres were included. Other criteria for inclusion were: age between 20 and 80 years, able to understand Swedish and physically and mentally capable of being interviewed, and not being under the influence of alcohol or drugs or suffering from dementia. Patients had to be able to wait for a physician's evaluation for at least one hour without medical risk, i.e. they should be at triage level four, and arrive at the healthcare facility by their own transportation. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Structured interview

The interview had a structured design and comprised 80 items. The questions were developed step by step. First, open questions were used in a pilot study and subsequently the answers were evaluated by a group with specialists from medical and social behavioural sciences. The final interview consisted of 80 items covering the following: the patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, perceptions of their symptoms, previous disorders, prior experiences and knowledge of the healthcare system, expectations, attitudes, use of healthcare information, and social network. This interview was tested in two additional pilot studies before the main study was conducted. The selection of questions used in this study was based on the primary aim of the investigation.

Data collection and processing

The interviews were conducted during a nine-week period from March to May 2002, Monday to Friday between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., at the ED of Stockholm Söder Hospital in Sweden and at the primary care centres. There were 19 interviewers who had been recruited and trained by the research team, and each interview was carried out just before the examination by the physician.

The reasons for the visit were categorized by the first author (ASB) into groups that corresponded to one of seven chapters of the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems, ICD-10 [18], [19]. The reasons for any visits that did not correspond to these large groups were classified as miscellaneous. Perceptions were measured by using a 10-grade visual analogue scale (VAS) [20].

Ethnicity was categorized on the basis of information on the patients’ and their parents’ origin. Employment status was classified into the following groups: (a) employed more than 75% of full time, (b) employed 25–75%, (c) employed less than 25% or unemployed, (d) retired, (e) receiving a disability pension.

The data were entered into Epidata 4.0. Recoding and univariate analyses were performed in SPSS 12.0.1 for Windows, and Statistica release 7. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by the binomial exact method in Excel for Windows. Ordinal data were analysed by the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Eligible patients

During the study period a total of 924 patients were eligible for the study (see Figure 1). Of these, 736 (80%) agreed to participate: 542 patients at the primary healthcare centres and 194 patients at the ED. The interview was interrupted by the physician in 1.8% of the study participants at the primary care centres and in 3.6% at the ED, or the patient did not want to answer all 80 questions. The loss is recorded as missing data.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics (Table I)

Table I.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Primary healthcare |

Emergency department |

|||||

| n = 542 | % | 95% CI | n = 194 | % | 95% CI | |

| Gender1 | ||||||

| Male | 193 | 36 | (32–40) | 92 | 49 | (42–57) |

| Female | 340 | 64 | (60–68) | 95 | 51 | (44–59) |

| Missing2 | 9 | 7 | ||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 20–34 | 122 | 23 | (19–27) | 44 | 24 | (18–30) |

| 35–49 | 179 | 34 | (30–38) | 59 | 32 | (25–39) |

| 50–64 | 122 | 23 | (19–27) | 45 | 24 | (18–30) |

| 65–80 | 111 | 21 | (18–24) | 39 | 21 | (15–27) |

| Missing2 | 8 | 7 | ||||

| Highest completed education | ||||||

| Compulsory school | 74 | 14 | (11–17) | 29 | 16 | (11–22) |

| Secondary school, high school | 246 | 46 | (42–56) | 95 | 51 | (44–59) |

| University | 208 | 39 | (35–43) | 61 | 33 | (26–40) |

| Education not specified | 3 | 1 | (0–2) | 2 | 1 | (0–3) |

| Missing2 | 11 | 7 | ||||

| Country of birth3 | ||||||

| Sweden | 453 | 85 | (82–88) | 159 | 86 | (81–91) |

| Other Nordic countries | 29 | 5 | (1–7) | 11 | 6 | (3–10) |

| Rest of Europe | 26 | 5 | (1–7) | 6 | 3 | (1–6) |

| Other | 24 | 5 | (1–7) | 10 | 5 | (2–9) |

| Missing2 | 10 | 8 | ||||

| Residency in Sweden | ||||||

| Whole life | 418 | 80 | (77–84) | 146 | 79 | (73–85) |

| Parts of life | 102 | 20 | (17–24) | 38 | 21 | (15–27) |

| Missing2 | 22 | 10 | ||||

| Parents’ country of birth | ||||||

| Sweden | 413 | 86 | (83–89) | 145 | 78 | (72–84) |

| Other Nordic countries | 5 | 1 | (0–2) | 21 | 11 | (6–16) |

| Rest of Europe | 32 | 7 | (5–9) | 10 | 5 | (2–9) |

| Other | 28 | 6 | (4–8) | 10 | 5 | (2–9) |

| Missing2 | 64 | 8 | ||||

| Married or cohabiting | ||||||

| Yes | 355 | 67 | (63–71) | 111 | 59 | (52–67) |

| No | 177 | 33 | (29–37) | 76 | 41 | (34–49) |

| Missing2 | 10 | 7 | ||||

| Children | ||||||

| Yes | 384 | 72 | (68–76) | 122 | 66 | (59–73) |

| No | 148 | 28 | (24–32) | 64 | 34 | (27–41) |

| Missing2 | 10 | 8 | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed ≥75% | 341 | 65 | (61–69) | 122 | 64 | (57–72) |

| Employed 25–74% | 19 | 4 | (2–6) | 10 | 5 | (2–8) |

| Employed < 25%4 | 13 | 3 | (2–5) | 3 | 2 | (0–5) |

| Disability pension | 43 | 8 | (6–11) | 19 | 10 | (6–15) |

| Retired | 113 | 21 | (18–25) | 36 | 19 | (14–25) |

| Missing2 | 13 | 4 | ||||

Notes: 1The proportion of men in the county of Stockholm was 49% in 2002. 2 Patients with missing values were excluded from the analysis. 3The proportion of foreign citizens in the county of Stockholm was 9.2% in 2002. 4The unemployment rate in the county of Stockholm was 3.3% in 2002. Inadequacy in percentages is due to rounding.

The proportion of women was higher at the primary care centres (64%, 95% CI 60–68) than at the ED (51%, 95% CI 44–59). The mean age of both the primary care and the ED group (both sexes combined) was 48 years. The groups were similar regarding age distribution, highest level of completed education, country of birth, being married or cohabiting, having children or not, and proportions of employed, unemployed, and disabled.

Past medical history

At the ED 43% of the patients were being monitored regularly for chronic diseases, compared with 35% of the primary care patients (difference 8%, 95% CI 0.1–16.4). The types of chronic diseases did not differ. A higher proportion of patients attending the ED had been admitted to a hospital within the last two years (35%, 95% CI 28–42), compared with primary care patients (21%, 95% CI 17–24).

In both groups a majority of the patients (>85%) had visited a physician at least once during the preceding two years. In the two groups the same proportion (43% at the ED and 42% at primary care) reported that they used regular medication. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the proportion of free care card holders between ED patients (33%, 95% CI 26–40) and patients receiving primary care (25%, 95% CI 21–29).

Chief complaints (Table II)

Table II.

Symptoms and signs at presentation.

| Primary healthcare |

Emergency department |

|||||

| n = 542 | % | 95% CI | n = 194 | % | 95%CI | |

| Organ system1 | ||||||

| Respiratory | 254 | 47 | (43–51) | 10 | 5 | (2–9) |

| Circulatory | 15 | 3 | (1–5) | 25 | 13 | (8–18) |

| Digestive | 28 | 5 | (3–7) | 45 | 23 | (17–29) |

| Genital and urinary tract | 46 | 9 | (7–12) | 17 | 9 | (5–13) |

| Skin | 37 | 7 | (5–9) | 4 | 2 | (0–5) |

| Muscle and skeletal | 72 | 13 | (10–16) | 39 | 20 | (14–26) |

| Trauma | 25 | 5 | (3–7) | 36 | 19 | (13–25) |

| Miscellaneous | 65 | 12 | (9–15) | 18 | 9 | (5–13) |

| Duration of symptoms | ||||||

| One day or less | 98 | 18 | (15–21) | 83 | 43 | (36–58) |

| One week or less | 222 | 41 | (37–45) | 76 | 39 | (32–46) |

| > One week | 218 | 40 | (36–44) | 35 | 18 | (12–24) |

| Missing2 | 4 | 0 | ||||

Notes: 1ICD–10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth revision. 2Patients with missing values were excluded from the analysis. Inadequacy in percentages is due to rounding.

At the primary care centres 47% (95% CI 43–51) of the patients had symptoms from the respiratory system, mainly infections and allergies. Some 13% (95% CI 10–16) had musculo-skeletal symptoms and 9% (95% CI 7–12) had symptoms from the genital or urinary tract. At the ED the most common symptoms were from the digestive system (23%, 95% CI 17–29) or the musculo-skeletal system (20%, 95% CI 14–26) or were due to trauma (19%, 95% CI 13–25).

The patients at the ED had had symptoms for a much shorter time than the primary care patients. Among the patients at the ED, 43% (95% CI 36–48) had experienced symptoms for one day or less, compared with 18% (95% CI 15–21) of the primary care patients. No differences in age distribution were found in the subgroup of patients with symptom duration of less than one day.

Patients’ perceptions

The patients at the ED were more anxious about their symptoms than the primary care patients (VAS: median 6, mode 10, interquartile range [IQR] 3 to 8 vs. median 5, mode 1, IQR 1 to 7, p < 0.001). The median age of the most anxious patients (VAS > 5) was similar at the two facilities.

The patients at the ED felt more disturbed by their symptoms than the primary care patients (VAS median 8, mode 10, IQR 6 to 10 vs. median 8, mode 8, IQR 5 to 9, p < 0.017). There was no significant age difference between the patients who were most disturbed (VAS > 5) and those who were least disturbed, at either facility. However, there was a tendency for the most disturbed ED patients to be younger.

Discussion

No major differences between non-urgent patients’ presenting at the ED and those attending primary healthcare centres were found regarding sociodemographic characteristics, except for gender. The patients presenting at the ED had more often been hospitalized during the past two years, they had different types of complaints, and their symptom duration before seeking care was shorter. Moreover, the patients were more anxious about and disturbed by their symptoms than those attending primary care. The results support the previous finding that patients visiting an ED also frequently use other healthcare services [21]. However, we found that this was also the case in primary care. This frequent use is further indicated by the finding of similarly high proportions of free-care card holders in both groups compared with the general population.

A major strength of our study is that it was based on patients from a well-defined source population within the geographical area of the primary care centre. Since we were able to compare patients with the same level of urgency we also minimized the possibility that selection bias would affect our results. The proportion of patients who declined to participate was virtually the same in the two settings, diminishing the risk of an effect of non-participation. We also consider that the generalizability of the results to the county of Stockholm and possibly to other large urban areas is high, since the distribution of completed education, the proportion of unemployed, and the proportion of immigrants were consistent with the general distribution in the county of Stockholm [15–17].

Most previous studies have compared non-urgent ED patients with urgent patients at an ED, but not with primary care patients [5–8]. The possibility of generalizing earlier findings concerning outpatient utilization has therefore been limited and we consider that this study provides important information on these patient groups [22]. Previous studies have also used perceived general health [23] or information on earlier admissions or visits obtained from retrospectively collected registry-based information [24] as indicators of the patient's condition. We conducted detailed, structured face-to-face interviews, thus enabling us to minimize the potential for information bias. We have not found any studies similar to ours in which data have been obtained in this way, apart from some analyses of mainly non-urgent or frequent ED attendees [5], [21], [25–27].

This study shows that symptoms, previous hospitalization, and current perception of symptoms are the main factors discriminating between patients seeking healthcare at an ED and those attending a primary care centre. If policy-makers feel a need to influence the seeking behaviour of patients, these factors need to be considered.

Future research should focus on the effects of different strategies on care-seeking behaviour.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anna Christensson, Olof Nyrén, Mia Pettersson, and Marie Reilly for valuable advice, help, and support, and Stockholm county council for financial support.

Ethics Committee

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee at the Karolinska Institutet (D nr 442/01).

Conflict of interest: none

References

- 1.Pereira S, Oliveira e Silva A, Quintas M, Almeida J, Marujo C, Pizarro M, et al. Appropriateness of emergency department visits in a Portuguese university hospital. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:580–6. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.114306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson LD, Hwang U. Access to care: A review of the emergency medicine literature. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1030–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padgett DK, Brodsky B. Psychosocial factors influencing non-urgent use of the emergency room: A review of the literature and recommendations for research and improved service delivery. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:1189–97. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sempere-Selva T, Peiro S, Sendra-Pina P, Martinez-Espin C, Lopez-Aguilera I. Inappropriate use of an accident and emergency department: Magnitude, associated factors, and reasons – an approach with explicit criteria. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:568–79. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.113464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afilalo J, Marinovich A, Afilalo M, Colacone A, Leger R, Unger B, et al. Nonurgent emergency department patient characteristics and barriers to primary care. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1302–10. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northington WE, Brice JH, Zou B. Use of an emergency department by nonurgent patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy AW, Leonard C, Plunkett PK, Brazier H, Conroy R, Lynam F, et al. Characteristics of attenders and their attendances at an urban accident and emergency department over a one year period. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:425–7. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.6.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David M, Schwartau I, Anand Pant H, Borde T. Emergency outpatient services in the city of Berlin: Factors for appropriate use and predictors for hospital admission. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:352–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mej.0000228451.15103.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajpar SF, Smith MA, Cooke MW. Study of choice between accident and emergency departments and general practice centres for out of hours primary care problems. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17:18–21. doi: 10.1136/emj.17.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham PJ, Clancy CM, Cohen JW, Wilets M. The use of hospital emergency departments for nonurgent health problems: A national perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52:453–74. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green J, Dale J. Primary care in accident and emergency and general practice: A comparison. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:987–95. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90238-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krakau I. Trends in use of health care services in Swedish primary care district: A ten year perspective. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1992;10:66–71. doi: 10.3109/02813439209014038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen MB, Christensen B, Mortensen JT, Olesen F. Intervention among frequent attenders of the out-of-hours service: A stratified cluster randomized controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2004;22:180–6. doi: 10.1080/02813430410006576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shipman C, Longhurst S, Hollenbach F, Dale J. Using out-of-hours services: General practice or A&E? Fam Pract. 1997;14:503–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Statistical yearbook from the county councils in Sweden. 2003. ISBN 91-7188-819-5 [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Health care and regional development. 2002. pp. 15–17. ISBN 91-7188-819-5 [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Statistical yearbook from the county councils in Sweden. 2005. ISBN 91-7164-005-3 [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day FC, Schriger DL, La M. Automated linking of free-text complaints to reason-for-visit categories and International Classification of Diseases diagnoses in emergency department patient record databases. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:401–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(03)00748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronsky D, Kendall D, Merkley K, James BC, Haug PJ. A comprehensive set of coded chief complaints for the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:980–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aitken RC. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62:989–93. doi: 10.1177/003591576906201005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansagi H, Olsson M, Sjoberg S, Tomson Y, Goransson S. Frequent use of the hospital emergency department is indicative of high use of other health care services. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:561–7. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.111762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe RA, Abbuhl SB. Appropriate standards for “appropriateness” research. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:629–32. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee A, Hazlett CB, Chow S, Lau F, Kam C, Wong P, et al. How to minimize inappropriate utilization of Accident and Emergency Departments: Improve the validity of classifying the general practice cases amongst the A&E attendees. Health Policy. 2003;66:159–68. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beland F, Lemay A, Boucher M. Patterns of visits to hospital-based emergency rooms. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:165–79. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, McGee HM, Murray A, Bury G. Frequent attenders to an emergency department: A study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:309–18. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun BC, Burstin HR, Brennan TA. Predictors and outcomes of frequent emergency department users. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:320–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergh H, Marklund B. Characteristics of frequent attenders in different age and sex groups in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003;21:171–7. doi: 10.1080/02813430310001149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]