Abstract

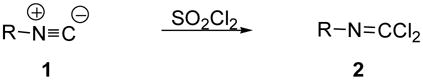

The reaction of aliphatic and aromatic isonitriles with sulfuryl chloride provides an efficient, general route to the corresponding dichlorides without byproducts of free-radical substitution.

Keywords: Carbonimidic Dichlorides, Isonitrile Dichlorides, Isonitriles

Isonitriles, which have been known for over 150 years, embody the only stable functional group containing a divalent carbon atom. As one consequence of their unusual electronic structure, isonitriles display a broad range of chemical reactivity with both nucleophiles and electrophiles. For that reason, isonitriles have long played a central role in the design and development of multicomponent reactions.i

Carbonimidic dihalides (also known as isonitrile dihalides; typically dibromides or dichlorides) have recently attracted attention in their own right, not only as protecting groups for isonitriles,ii but also as building blocks for more complex molecular architectures.iii Carbonimidic dibromides can usually be prepared by simple addition of elemental bromine to the isonitrile. However, as noted in a seminal review,iv the comparable addition of elemental chlorine (Cl2) to isonitriles is not a generally useful reaction with alkylisonitriles, since free-radical processes generally produce alkyl chloride byproducts resulting from C-H substitution.

Here we report that the chlorination of isonitriles 1 using sulfuryl chloride rapidly and selectively furnishes the corresponding carbonimidic dichlorides 2 (Eqn 1). Besides being readily available, inexpensive, and quite convenient to use, sulfuryl chloride is also easy to purify and manipulate in small quantities for benchtop experimentation.

|

Eqn 1 |

Sulfuryl chloride has long been known as both an excellent chlorinating and sulfonylating agent for aromatic compounds, depending on the choice of experimental conditions.v Aliphatic chlorination of hydrocarbons can also be achieved either under ionic conditions, using Lewis acid catalysts, or under free radical conditions in the presence of a suitable catalyst (peroxides) or light. However, in the absence of such free radical initiators, aliphatic chlorination can largely be suppressed at low temperatures. This exquisite control of product outcomes, as summarized in a recent review,vi has led to a resurgence of interest in sulfuryl chloride on the part of academic and industrial researchers.vii

Using cyclohexylisonitrile as a test case, neat SO2Cl2 (1 equiv) was added dropwise to a stirred CH2Cl2 solution (1.0 M) of the isonitrile at −20 °C under nitrogen and the reaction mixture warmed to rt (15–30 min total reaction time). The desired carbonimidic dichloride was obtained in nearly quantitative yield and exhibited the expected 9:6:1 ratio of M:M+2:M+4 peaks characteristic of two chlorine atoms in the structure. Applying the same procedure to n-butylisonitrile led to product contaminated with 10–15% chain-chlorinated byproducts. However, by lowering the reaction temperature to −45 °C and pre-diluting the SO2Cl2 with CH2Cl2, the product n-C4H9N=CCl2 was obtained ca 95% pure.

Chlorinations of representative isonitriles 1a–1f using SO2Cl2 at −45 °C are summarized in the Table and illustrate the broad scope and efficiency of the method. Both aliphatic and aromatic isonitriles are readily converted to the corresponding dichlorides in excellent yield. Although carbonimidic dichlorides 2a–2e have previously been synthesized (as referenced in the Table), very little spectroscopic or physical characterization (other than IR and mp) data was provided in earlier publications. All products 2a–2f were fully characterized by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, IR and either chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS) or electron impact mass spectrometry (EIMS). The product carbonimidic dichlorides could be stored neat at −20 °C for up to 4–5 days without appreciable decomposition, but NMR samples deteriorated appreciably upon standing at rt after 1–2 d.

Table.

Synthesis of Isonitrile Dichlorides Using Sulfuryl Chloride

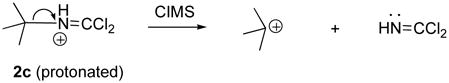

When dichloride 2c was analyzed using CIMS, no parent ion could be detected. However a strong signal at m/z 57 was observed, which likely arose from the fragmentation shown in Eqn 2. By contrast, analysis of 2c using EIMS did reveal the expected M, M+2 and M+4 pattern of parent ions as well as characteristic fragment ions arising from both α-cleavage and inductive cleavage pathways.

|

Eqn 2 |

Data in the Table confirm that the reaction is compatible with other functionality, including carboxylic esters. Moreover, no aromatic chlorination products were detected. In a competition experiment between cyclohexylisonitrile and 1-decene, dichloride 2b was formed exclusively (94%) and 1-decene was returned unchanged, indicating high selectivity for chlorine addition to the isonitrile in the presence of an alkene. Furthermore, isonitriles 1d–1f selectively underwent addition in preference to substitution, even in the presence of activated methyl and methylene groups (e.g. CH3–Ar in 1d; – SO2CH2 – in 1e; – CH2CO2Et in 1f).

EXPERIMENTALxii

Representative Procedure for the Chlorination of Isonitriles Using SO2Cl2

A magnetically-stirred CHCl3 solution of isonitrile (0.7–1.0 mmol) under N2 in an oven-dried 25 mL RBF was cooled in a Dry Ice-CHCl3 bath to −45°C. A solution of freshly distilled SO2Cl2 (1 equiv) in CHCl3 (1 M) was added dropwise via microsyringe over 10 min and the resulting solution was stirred for 10 min, then allowed to warm to rt. The desired product was obtained by concentrating the solution on a rotary evaporator and briefly exposing the residual oil to a vacuum line (0.1 – 0.25 torr, 1–2 min) to remove last traces of solvent. The product carbonimidic dichlorides were characterized without further purification.

n-Butylcarbonimidic dichloride (2a)

1H-NMR δ 3.49 (t, 2 H, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.59–1.65 (m, 2 H), 1.36–1.40 (m, 2 H), 0.94 (t, 3 H, J = 7.4 Hz); 13C-NMR δ 123.4, 54.6, 31.3, 20.3, 13.6; IR 1654; CIMS m/z 154 (MH+), 156 (MH++2), 158 (MH++4).

Cyclohexylcarbonimidic dichloride (2b)

1H-NMR δ 3.52–3.58 (m, 1 H), 1.22–1.88 (m, 10 H); 13C-NMR δ 121.7, 63.9, 32.2, 25.4, 24.2; IR 1644; CIMS m/z 180 (MH+), 182 (MH++2), 184 (MH++4).

tert-Butylcarbonimidic dichloride (2c)

1H-NMR δ 1.39 (s, 9 H); 13C-NMR δ 116.4, 59.9, 28.5; IR 1648; EIMS m/z 153 (M+), 155 (M++2), 157 (M++4); 138, 140, 142 (loss of CH3); 57 (base peak).

(2-Methylphenyl)carbonimidic dichloride (2d)

1H-NMR δ 7.25 – 7.17 (m, 3 H), 7.13 (td, 1 H, J = 7.5, 1.4 Hz), 6.82 (dd, 1 H, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz), 2.17 (s, 3H); 13C NMR δ 144.5, 130.6, 128.4, 126.4, 125.9, 118.9, 17.6; IR (cm−1) 1647; CIMS (electron impact, m/z): 188 (MH+), 190 (MH++2), 192 (MH++4).

{[(4-Methylphenyl)sulfonyl]methyl}carbonimidic dichloride (2e)

1H-NMR δ 7.83 (d, 1 H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.79 (s, 2 H), 2.47 (s, 3 H); 13C-NMR δ 145.7, 134.0, 129.9, 129.0, 128.8, 73.9, 21.7; IR 1650; CIMS m/z 266 (MH+), 268 (MH++2), 270 (MH++4).

Ethyl [(dichloromethylidene)amino]acetate (2f)

1H-NMR δ 4.29 (s, 2 H), 4.26 (q, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.30 (t, 3 H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C-NMR δ 167.3, 129.9, 61.7, 55.6, 44.1, 14.1; IR 1662; CIMS m/z 184 (MH+), 186 (MH++2), 188 (MH++4).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for HVL was provided by the NIH (GM 008500 Training Grant). Support of the Cornell NMR Facility has been provided by NSF (CHE 7904825; PGM 8018643) and NIH (RR02002).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA: Full 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, infrared and mass spectra are provided for all compounds reported in the Table (25 pages). Supplementary data can be found online at ScienceDirect.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- i.(a) Domling A, Ugi I. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:3188. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::aid-anie3168>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nair V, Rajesh C, Vinod AU, Bindu S, Sreekanth AR, Mathen JS, Balagopal L. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:899. doi: 10.1021/ar020258p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ii.O’Neil IA. The Synthesis of Isocyanides. In: Katritzky AR, Pattenden G, Meth-Cohn O, Rees CW, editors. Comprehensive Organic Functional Group Transformations. Vol. 3. 1995. p. 693. [Google Scholar]

- iii.El Kaim L, Grimaud L, Patil P. Org Lett. 2011;13:1261. doi: 10.1021/ol200003u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iv.Kuhle E, Anders B, Zumach G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1967;6:649. [Google Scholar]

- v.Brown HC. Ind Eng Chem. 1944;36:795. [Google Scholar]

- vi.Moussa VN. Aust J Chem. 2011;65:95. [Google Scholar]

- vii.(a) Yu M, Snider BB. Org Lett. 2011;13:4224. doi: 10.1021/ol201561w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson JW, Evanoff DP, Savad ME, Lange G, Ramadhar TR, Assoud A, Taylor NJ, Dmitrienko GI. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6970. doi: 10.1021/jo801274m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- viii.Tanaka S. Bull Chem Soc Japan. 1975;48:1862. [Google Scholar]

- ix.(a) Ulrich H, Sayigh AAR. J Chem Soc. 1963:5558. [Google Scholar]; (a) Kühle E, Anders B, Zumach G. Angew Chem. 1967;79:663. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schroth W, Kluge H, Frach R, Hodek W, Schädler HD. J Prakt Chem. 1983;325:787. [Google Scholar]

- x.(a) Dyson GM, Harrington T. J Chem Soc. 1940:191. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sayigh AAR. J Chem Soc. 1963:3146. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houwing HA, Wildeman J, Van Leusen AM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976:143. [Google Scholar]

- xii.1H-NMR spectra (400 MHz) were taken using CDCl3 with 0.05% v/v TMS as solvent. Spectra were recorded in δ (ppm) and referenced to TMS (0.00 ppm). 13C-NMR spectra (100 MHz) were taken using CDCl3 with 0.05% v/v TMS as solvent. Spectra were recorded in δ (ppm) and referenced to CDCl3 (77.16 ppm for 13C NMR). IR spectra were recorded using an FT-IR spectrometer and recorded in wavenumbers. Mass spectra were taken using acetonitrile (for electron impact) or cyclohexane (for chemical ionization) solutions. NOTE: Most isonitriles have extremely unpleasant odors; therefore, all operations should be conducted in a well-ventilated hood.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.