1. Introduction

The CANTAB (Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery) has been widely used in human neuropsychiatric and pharmacological studies to assess cognitive function and neurodevelopment (Robbins et al. 1997; Dorion et al. 2001; Ozonoff et al. 2004; Canfield et al. 2004; Jazbec et al. 2007; Levaux et al. 2007; McKirdy et al. 2009). Due to the non-verbal nature of the test administration, the same neuropsychological testing approaches using the CANTAB have been successfully adapted to assess behavior in nonhuman primate species and to date studies have been conducted in two nonhuman primate species: the common marmoset and the rhesus monkey (Collins et al. 1998; Weed et al. 1999; Taffe et al. 1999; Golub 2002; Spinelli et al. 2004; Muggleton et al. 2005; Nagahara et al. 2008; Weed et al. 2008).

The baboon is another nonhuman primate species that has been studied to evaluate several functional systems and offers many structural and functional opportunities for research that translate more closely to human physiology. For example, this is especially true in the area of reproduction where mothers almost always carry a single fetus and the placenta is generally a single disc (Carter 2007). This species has also been used extensively for studies on fetal and neonatal endocrine development and growth (Pepe & Albrecht 1995; Cox et al. 2006a; Cox et al. 2006b; Li et al. 2007; Nijland et al. 2007; Schlabritz-Loutsevitch et al. 2009).

In order to build on this important translational utility of the baboon model, we aimed to determine whether the CANTAB system for behavioral studies could be successfully administered in this species. We describe here the adaptation of the CANTAB system and protocols for use in juvenile baboons at 3 years of age. The subjects were tested on the progressive ratio task to assess motivation to respond for food reinforcement and on simple discrimination (SD) and reversal (SR) tasks to assess associative learning. We also implemented the intra- and extra-dimensional set-shifting task (IDED) to assess selective attention and prefrontal cortex dependent attentional set-shifting.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

All procedures were approved by the Southwest Foundation Biomedical Research (SFBR) and University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Subjects were 8 baboons (Papio sp.), 4 females and 4 males, their age at onset of the study was 3.0 ± 0.1 years and weight was 8.2 ± 0.4 kg (weight average within normal baboon growth trajectory (Glassman et al. 1984)). All baboons were born, breast fed and reared by their mothers in group housing at the SFBR (Schlabritz-Loutsevitch et al. 2006). These subjects served as control animals in a separate study. As such, mothers received two intramuscular saline injections 24h apart at 0.60, 0.65 and 0.70 of gestation. Subjects were group housed with their mothers until transferred to the University of Texas Health Science Center’s Laboratory Animal Resources facility where they were habituated to single cage housing for one month prior to onset of the study.

Training and testing were conducted between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., Monday through Friday. If an animal was tested in the morning (9-11:30 a.m.), feeding occurred at 12 and 5 p.m. or if tested in the afternoon (1-4 p.m.), feeding occurred at 9:00 a.m. and 5 p.m. Subjects were fed nonhuman primate chow (2050 Teklad Global 20% protein, 2.7 kcal/g metabolizable energy, Harlan Laboratories, USA) no less than 4 hours preceding behavioral sessions and at the end of the day (5 p.m.) with the exception of the progressive ratio task. For the progressive ratio task, each subject was fed 2 hours before the task was administered regardless of when the animal was tested and a second time at 5 p.m. Daily chow rations were calculated prior to training by administering food ad libitum, over a course of two weeks and measuring consumption. Each subject would then be fed half this amount twice per day over the course of the study (3 months). In this manner feed was adjusted to each individual subject and no refusal to eat was observed. Water was available ad libitum. As a form of enrichment and dietary supplement, subjects also received fruits in the late afternoon after behavioral testing three times a week and vitamins given in treats. The light cycle was set such that light went on at 7 a.m. and off at 9 p.m.

2.2 CANTAB apparatus

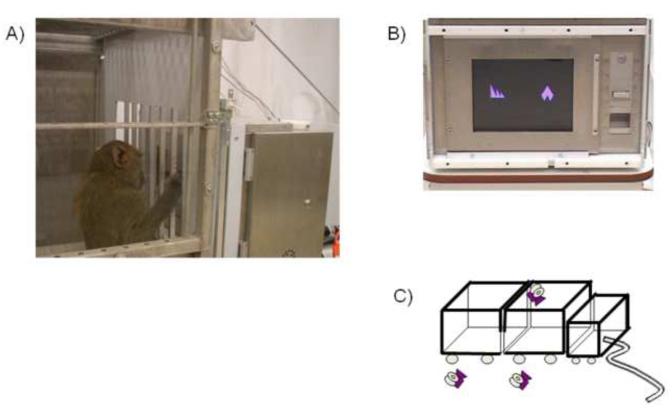

The Monkey CANTAB software and apparatus (models 80650/80652*C, Lafayette, Indiana, USA) were used to conduct behavioral testing. The testing station was constructed of an aluminum chassis incorporating a computer monitor with an infrared touch-screen, a pellet dispenser (model 80209, Campden Instruments Ltd., Lafayette, IN, USA) and pellet trough situated onto a moveable trolley (Figure 1). This trolley was attached to a testing cage that was a modified home cage. During training and testing the home and testing cage were securely connected to one another allowing the animal to move freely between the two cages and permitting access through the bars of the testing cage to manipulate the CANTAB touch-screen monitor situated 14 cm away. This set-up allowed testing the subjects under conditions associated with less stress than situations under which the subject is removed from its environment (Scott et al. 2003; Weed et al. 2008) and provided sufficient structural integrity, which is a requirement when testing stronger nonhuman primates. The controlling computer (IBM compatible Pentium IV) and LCD monitor were connected to the testing station by a 10-m cable and were located behind a partition curtain in the testing laboratory out of the test subjects’ eyesight. This computer controlled the CANTAB software which generated the visual stimuli, task parameter/contingencies, and recorded the number of trials and errors made. The computer monitor ran in parallel with the touch-screen monitor in order to display the location of the subject’s touches in real-time to the experimental observer. Two video cameras (Sony Handycam DCR-SR40) were positioned to give an optimal view of the home cage and the testing cage in order to be able to later score the subject’s behavior during testing. Additionally, a remote camera (X10 Wireless Technology XC18A) was placed on top of the testing cage so that the experimenter had a good view of the subject and the CANTAB apparatus. Subjects were first familiarized with the testing cage, CANTAB set-up, and cameras before training and testing began.

Figure 1.

CANTAB testing configuration. A) Baboon reaching through the testing cage bars to interact with B) the CANTAB computer touch screen monitor. C) Schematic illustration of the camera placement, home cage (left box), testing cage (center box) and CANTAB monitor (right box).

2.3.1 Reinforcement familiarization

The aim of the reinforcement familiarization task was to teach the baboons that the onset of a 2 sec (1-kHz) reward tone signaled the availability of reinforcement. This reward tone was the standard signal for the availability of reinforcement across all tasks. The reward, a 190 mg banana flavored precision pellet (model F0035, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA) was administered every 15 seconds and did not require an operant response from the subject. During reinforcement familiarization, the subjects learned to retrieve the pellet from a trough. The criterion to complete reinforcement familiarization was consumption of 75% (40 of 52) of the reward pellets per session. A minimum of 3 sessions was required. The number of sessions needed to reach criterion was scored.

2.3.2 Initial touch screen training

Touch screen training began once the subjects had completed reinforcement familiarization. Training built upon classical and operant conditioning paradigms based on procedures described in Roberts et al., (1988), Pearce et al., (1998) and Spinelli et al., (2004). The sessions varied in length, inter-trial interval (ITI), size of the responsive area, and location of the responsive area on the screen (see Table 1). For the first sessions the screen was baited with banana. Once the subjects were responding to the un-baited screen, session length was increased to 30 min and the size of the responsive area was made smaller after 10 consecutive correct touches. Missing the stimulus resulted in trial termination and was accompanied by a 0.2 sec 40-Hz (punishment) tone. Six different stimulus sizes were used, starting with the whole screen and ending with a 6 cm square, with all stimuli presented in the center of the screen. The program settings for touch detection were set to strict criteria so that the subjects could not slide their hand onto the stimulus and had to remove their hand from the screen before making another response.

Table 1.

Overview of initial touch screen training stages and criteria to proceed.

| Session type |

Help on screen |

Session length |

ITI | Stimulus size and location |

Criterion to proceed to next stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage A | Baited with little banana |

15 min | 1 sec | Whole screen | Subject shows interest and takes rewards |

| Stage B | Baited with very little banana |

15 min | 3 sec | Whole screen | Subject takes rewards and works for at least 10min |

| Stage C | No help | 15 min | 5 sec | Whole screen | Subject touches un-baited screen, takes rewards and works for at least 10min |

| Stage D | No help | 20 min | 5 sec | First session starts with whole screen and each subsequent session starts with the smallest size mastered on last session, but not smaller than 6 × 6 cm. Stimulus is presented in center of the screen and shrinks after 10 consecutive correct trials. |

Subject completed 2 sessions that started with 6 × 6 cm |

| Stage E | No help | 20 min | 5 sec | A 6.2 × 4.4 cm rectangle is presented in 9 different locations |

3 sessions |

Once the subjects were able to reliably touch the small square, they were trained with a rectangle that was 6.2 × 4.4 cm, which was smaller than the stimuli they would encounter during SD/SR and IDED sessions. This stimulus appeared in one of nine locations on the screen per trial for three sessions.

2.4 Progressive Ratio

The progressive ratio protocol was based on that developed for rhesus and marmosets (Weed et al. 1999; Spinelli et al. 2004) but modified for the baboon. Subjects were required to touch a single large (10 cm square) purple stimulus presented in the center of the screen. Each successful screen touch was secondarily reinforced by the screen changing color (to black) for 0.1 second. Response requirements to obtain a successive reinforcement progressively increased: beginning with 1 and increasing by 1 for the first eight reinforcements. Thereafter, the increment doubled every 8th reinforcement. Thus, the number of responses required increased according to the following schedule: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, (ratio increment =1); 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22 (ratio increment =2); 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, 46, 50 (ratio increment = 4); etc. Each session lasted a maximum of 30 minutes but was terminated early if the subject did not respond within a 3-minute period (breaking point). As was the case in the protocol described by Spinelli et al., (2004), the maximal session duration as well as the time period during which an operant response was required, were chosen so that achieved performance was a measure of the true break point for each subject. The two reward pellets were delivered automatically when the number of responses required had been reached. After 3 training sessions subjects were tested for 10 sessions.

Subjects were fed 2 hours prior to each session and the subjects’ motivation to respond for palatable reward was measured. The dependent variables derived from the progressive ratio schedule were total number of screen touches, total number of reinforcements obtained, and time between session onset and last operant response.

2.5.1 Touch screen training for simple discrimination

In contrast to the single stimulus displayed in the center of the screen during the previous touch screen training and progressive ratio task, the stimuli for the discrimination training tasks were presented to the left and right of center on the screen. Three sessions of this training were administered with a single stimulus presented in one of the two locations where the stimulus would be presented during the SD training and testing tasks. The stimulus used was smaller in size than those that would be presented during testing to ensure operant touch accuracy. This additional training, an adaptation from previous nonhuman primate versions, was introduced because some baboons need a few trials to familiarize to the new stimuli locations. It also acted as a control for motor function.

2.5.2 Simple discrimination and simple reversal

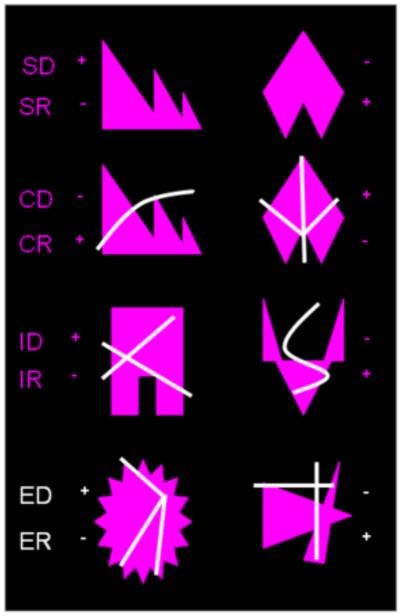

Repeated simple discrimination (SD) and reversal (SR) tasks were administered to assess indices of associative learning and in order to pre-train for the IDED test (Weed et al. 2008). There is some evidence that non-human primates might have a preference to shapes over lines. This was not investigated, but to avoid any potential confound caused by an inherent dimension preference, the first relevant dimension were purple shapes and the second dimension were white lines for all the subjects tested. Subjects were first presented with repeated administration of five different SD tasks (SD1-5), during which two purple stimuli that differed in shape were presented randomly and simultaneously to the left and right of the center on the touch screen (Figure 2). Note: Lines stimuli were not presented during training only during the IDED test. Touching one of the stimuli resulted in reinforcement delivery. Thus, subjects used trial and error to learn which stimulus was positively reinforced. The stimulus-reward association was considered acquired when the subject made 8 consecutive correct responses.

Figure 2.

Overview of the 8 IDED stages. Figure adapted from Pearce et al. (1998). Plus signs indicate positively reinforced stimuli, while negative signs indicate incorrect stimuli.

During the SR task, the subjects first learned to discriminate between the stimuli as described above. Once the rule was learned, the reward contingencies were reversed, and responding to the previously unrewarded stimulus now yielded reinforcement. There were 3 pairs of SD/SR tasks (SD6 followed by SR1, SD7 followed by SR2 and SD8 followed by SR3). In total there were eight SD (SD1-8) and three SR (SR1-3) training tasks.

For all discrimination tasks, a correct response was reinforced with 2 banana-flavored pellets and accompanied by the reward tone. An incorrect response was followed by absence of reinforcement and punishment tone. The ITI was 5 seconds for both correct and incorrect trials. Maximum session length was 30 minutes. For each task novel stimuli were used. Subjects were allowed to complete multiple discriminations tasks within the allotted session time. The stimuli used were taken from the Cambridge Cognition stimulus sets 5 to 8. The dependent variable measured was errors made per task.

2.6 Intra-dimensional and extra-dimensional set-shifting task

Following training for SD and SR tasks, subjects were tested on the intra- and extra-dimensional set-shifting task (IDED) discrimination series using the Cambridge Cognition stimulus set 0. The sequence consisted of an eight-stage series of discriminations as described by Weed et al., (1999) for rhesus macaques. For all subjects the first relevant dimension was shape.

All test stages are depicted in Figure 2. The first two stages of the test were a SD and a SR. In the third stage, compound discrimination (CD), the stimulus was composed of the previously reinforced shape dimension of the SR stage superimposed with a line. The subject was required to respond to the previously rewarded dimension (i.e. shape). The shape and line stimuli randomly changed sides independently of each other. Once learning criteria had been achieved, reinforcement conditions were reversed during compound reversal (CR), the fourth stage. In the fifth stage, the intra-dimensional shift stage (ID), a new pair of shape and line stimuli were presented with the dimension of shape still associated with reinforcement. In the sixth stage, intra-dimensional shift reversal (IR), the stimulus rewarded was the previously unrewarded shape stimulus. In the seventh stage, the extra-dimensional shift stage (ED), new shape and line stimuli were presented. This time, responding to one of the stimuli of the other dimension (i.e. line) yielded reinforcement. The subjects therefore had to shift their attention from the previously rewarded dimension to the newly rewarded dimension. In the eighth and final stage, extra-dimensional shift reversal (ER), responding to the previously unrewarded stimulus of the same dimension yielded reinforcement.

A correct response yielded 2 banana pellets and was accompanied by the reward tone. Incorrect responses led to no reinforcement and the punishment tone. Inter-trial interval was 5 seconds. The learning criterion was again 8 consecutive correct trials. When compound stimuli where used, the combination of the line and shape stimuli were random, as was the presentation of the stimulus to the left or right side of the touch screen. Maximum session length for the IDED series was 30 minutes. If a given stage was not completed by the end of a daily test session, the next session began at the same stage with the performance criteria reset (Weed et al. 1999). The dependent variable measured was errors made per stage.

2.7 Data analysis

All data were square root transformed prior to analysis to ensure normal distribution. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 and statistical significance was accepted for p values < 0.05. One way ANOVA was used to determine differences between the training tasks or testing stages and followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test.

3. Results

3.1.1 Reinforcement familiarization

All subjects completed reinforcement familiarization within 3 days and consumed 95.6 ± 3.1 % of all rewards.

3.1.2 Initial touch screen training

All baboons were able to reliably touch the un-baited screen after 3 sessions. During the stage at which the box size was reduced after 10 consecutive correct touches, subjects required an average of 6.8 ± 1.3 sessions to successfully respond to the smallest box size of 6 cm. In the subsequent 3 sessions, during which the stimulus was presented in 9 different locations, performance reached 79.0 ± 4.0 % correct responding in the final session.

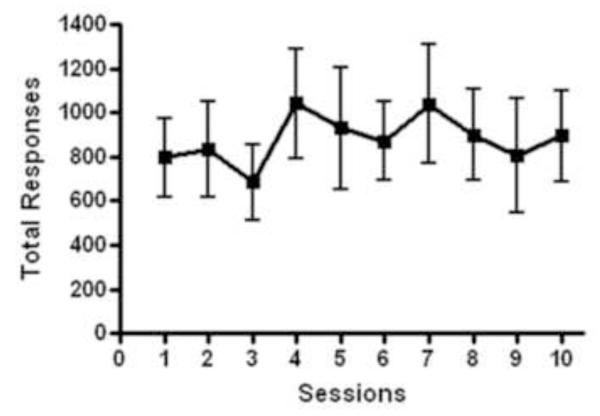

3.2 Progressive Ratio

Performance across 10 sessions of progressive ratio was stable, as analysis confirmed no main effect of session [F(9,63)=1.862, p>0.05, Figure 3] for total responses. The average number of responses made was 880 ± 210.1 and time between session onset and last operant response was 1237 ± 139.6 seconds (breakpoint) from a potential session length of 1800 seconds.

Figure 3.

Total responses made in the progressive ratio task over 10 session showing stable performance with no effect of session over time (n=4 males, n=4 females, p>0.05). Data presented as group averages (+ SEM).

3.3.1 Touch screen training preceding discrimination task

Analysis confirmed that in the 3 sessions of the second touch screen training, performance increased across sessions [F(2,14)=4.970, p<0.05] and reached 84.0 ± 3.3 % correct responses in the final session.

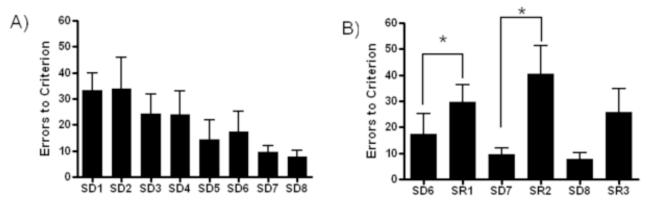

3.3.2 Simple discrimination and Simple reversal

Figure 4 A) and B) shows the performance across SD and SR sessions. Subjects’ performance improved across SD1-8 tasks. Analysis confirmed significant improvement in performance from the SD1 to SD8, as measured by errors made [F(7,49)=2.320, p<0.05]. There was a significant effect of tasks in the 3 pairs of SD/SR’s and post-hoc analysis confirmed subjects made significantly more errors during both SR1 versus SD6 and SR2 versus SD7 [F(5,35)=5.904, p<0.05]. There was no difference between SD8 and SR3, and there was no effect across the SR’s.

Figure 4.

A) Analysis of the performance, as measured in number of errors to criteria across the eight SD tasks (SD1 – SD8) revealed a significant effect (p<0.05). B) An effect was found across the SD/SR tasks, with post-hoc indicating more errors made in the SR1 versus SD6 and SR2 versus SD7 task (n=4 males, n=4 females; *, p<0.05). Data presented as group averages (+ SEM).

3.4 Intra-dimensional and extra-dimensional set-shifting task: IDED task

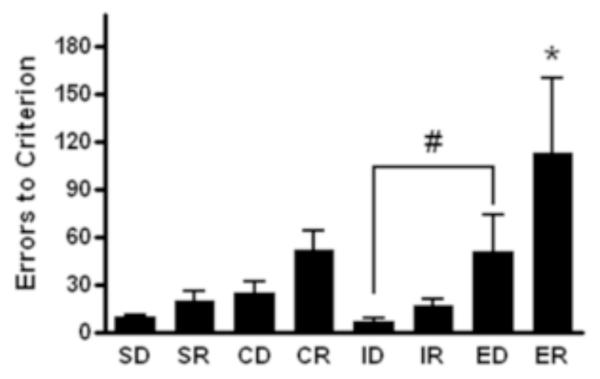

There was an overall effect of stage during testing [F(7,49)=10.01, p<0.05, Figure 5]. However, no differences were detected when comparing the CD and ID stages. Although, significantly more errors were made in the ED stage than in the ID stage (p<0.05). Furthermore, more errors were made at the ER stage than at all other stages (p<0.05). Additionally, significantly more total trials (sum of correct and incorrect trials) were required to reach criterion during the CR and ED stages than during the ID stage (p<0.05, Table 2). An increased number of total trials was required to learn the rule at the ER stage than at all other stages (p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Analysis of performance on the intra- and extra-dimensional set-shifting test, as measured by errors to criteria, for each of the 8 stages revealed differences; * indicates a difference as compared to all other stages and # a difference between ED versus ID stages (n=4 males, n=4 females; p<0.05). Data presented as group averages (+ SEM).

Table 2.

Trials to criterion for the 8 stages of the intra- and extra-dimensional set-shifting task.

| Stage | SD | SR | CD | CR | ID | IR | ED | ER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 31.1 | 41.8 | 64.5 | 92.8 | 21.9# | 42.8 | 120.1 | 240.3* |

| SEM | 4.2 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 17.8 | 5.6 | 10.0 | 53.3 | 87.0 |

ID was significantly different from ED and CR (p<0.05);

ER was significantly different to all other stages (p<0.05).

4. Discussion

Consistent with the mission of the NIH, the proposed study was conducted with the aim of developing methods to maximize translation of results from animal models to the human condition. The CANTAB system is a standard method of assessing individual differences in cognition, behavior and emotion in school-age children (Luciana 2003; Rhodes et al. 2005). Thus, by establishing the validity and reliability of the CANTAB in the baboon we have expanded the application and increased the opportunities for research that translates closely to human development, including fetal and neonatal development.

In this section we discuss the considerations in adapting the CANTAB methods from those established for marmosets and rhesus macaques, the measurement of motivation, and the results on simple and reversal discrimination and attentional set-shifting tasks.

Training

Home cage training was favored because it exposed the subject to less stress than a change of housing (Scott et al. 2003) and has previously been successfully used in marmosets (Spinelli et al. 2004) and rhesus monkeys (Weed et al. 2008). Testing physically strong nonhuman primates, such as baboons, in their home cage required careful construction of a testing cage that was connected on one side with the home cage and on the other side with the testing apparatus. The testing cage had to be strong and stable, while still allowing the subject to easily reach the touch screen as well as the reward trough. By drawing on the protocols developed for marmosets and rhesus macaques (Weed et al. 1999; Spinelli et al. 2004), and taking the special needs of the baboon into account in designing the testing apparatus, we were able to successfully design a system that permits administration of the CANTAB to juvenile baboons.

All baboons readily and quickly acquired the necessary operant responses for pellet reinforcement. The stage at which variability across subjects was highest was the stage at which the box shrunk after 10 consecutive correct responses. The latency to acquire such operant response criterion, which reflects both cognitive and motor skill, would constitute an interesting measure of comparison in future studies. As in the human, latency to skill acquisition is an important metric of flexibility and adaptability.

Measure of motivation

Progressive ratio (PR) session length as well as breakpoint duration (the maximum time allowed for inactivity before termination of the session) were adapted to avoid any ceiling effects and to maximize measurement of optimal performance. The specific schedule used (increment ratio and 30 min sessions), combined with a 3-minute breakpoint resulted in most baboons reaching a breakpoint. Those that did not, (i.e., those whose periods of inactivity lasted less than 3 minutes) exhibited severely decreased responses towards the end of the 30-minute session indicating decreased motivation as the session time elapsed. The measures scored therefore represent sensitive measures of motivation. In addition, as reported for marmosets (Spinelli et al. 2004), the inter-individual differences in motivation were evident but accompanied with a stable responses over sessions. Breakpoint results demonstrate that the average time spent performing the progressive ratio task was 21 minutes for all subjects.

Simple discrimination and simple reversal

The administration of multiple SD tasks allows for measurement of initial rule acquisition and associative learning and has been demonstrated previously in the rhesus (Weed et al. 2008). In the present study, subjects improved performance across the SD tasks. Additionally, SR tasks are important in revealing a subject’s propensity to display perseverative behavior, which suggest difficulty with associative learning rule changes. As expected, more errors were made in the SR1 and SR2 tasks as compared to SD6 and SD7, respectively with no difference in errors in the SR3 versus the SD8 task. The SR task in nonhuman primates is believed to be orbitofrontal cortex dependent, as lesions of that area in marmosets result in impairment of reversal learning of a stimulus-reward association (Dias et al. 1996).

Intra- and extra-dimensional attention set-shifting

The IDED test is a powerful behavioral tool with the potential for high impact in assessing selective attention and attentional set-shifting. It’s utilization in nonhuman primates has been limited (Dias et al. 1996; Dias et al. 1997; Weed et al. 1999; Crofts et al. 1999; Muggleton et al. 2005; Weed et al. 2008). Our results did not show an effect in the intra-dimensional shifting stage, as indicated by the non-significant difference between the CD and ID stages and consistent with the formation of an attentional set for the first dimension presented (i.e. shape). Furthermore, significantly more errors were made in the ED stage versus the ID stage, which suggests increased difficulty in shifting from the established attentional set to the second set presented. The subject’s attention to the first dimension, which in the ED stage was irrelevant, resulted in increased errors. The increased errors made in the ED test stage compared to the ID stage has been demonstrated in humans, rhesus, and marmosets (Roberts 1996; Weed et al. 1999; Weed et al. 2008), further confirming the potential use of these tests in the juvenile baboon. Because shapes were always the first relevant dimension, we cannot conclude that the subjects learned to selectively attend to one dimension. It is possible that the baboons had an inherent preference to shapes, which made the shift to the second dimension more difficult. Dimension preference has also been described in humans (Medin 1973; Schmittmann et al. 2006).

Studies of lesions to the lateral prefrontal cortex show impaired attentional set-shifting abilities both in common marmosets and humans (Roberts 1996; Dias et al. 1996). Human translational information can be gained from this attentional set-shifting task, given that there is good support for behavioral homology across species. In contrast to the human, our ER results are similar to those reported in rhesus macaques in that the baboons needed more trials to reach criterion in the ER stage versus the ED stage. This has been interpreted as an absence of a generalization of the newly relevant dimension during the ED to ER stage (Weed et al. 1999; Weed et al. 2008). Although cross species comparisons are challenging given the differences in criteria for successful advancement to subsequent IDED test stages, the behavioral profile of juvenile baboons was most like the adult rhesus performance (Weed et al. 2008). The two species demonstrated similar amounts of time required to learn the tasks, and both old world monkeys acquired the tasks significantly faster (in the scope of weeks) than common marmosets (new world monkeys).

In contrast to other CANTAB tasks, the attentional set-shifting task has been used most often in longitudinal studies. This may be due to the difficulty in linking more acute challenges (such as pharmacological interventions) with specific test stages and the complication of attenuating stage effects with repeated administration. Utilizing novel stimuli in multiple testing periods may be one approach to increasing the utility of the CANTAB IDED for comparing performance across time (between different tests) or subsequent to pharmacological challenges. Because performance of the IDED test requires adequate functioning of prefrontal cortical areas as well as other limbic structures (e.g., hippocampus and striatum) performance on the IDED test can be used to assess dysfunctional development of these areas due to experimental manipulation at different periods of development. We note that the CANTAB IDED test is only one version of touch-screen tests of attentional set-shifting; other laboratories have used similar tests (Decamp & Schneider 2004; Decamp & Schneider 2006) or other attentional set-shifting tasks that are arguably more faithful to the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test than the CANTAB IDED (Moore et al. 2003; Moore et al. 2005; Baxter & Gaffan 2007; Voytko et al. 2009).

In conclusion, the present study established that baboons can easily be trained on the neuropsychological test battery and be tested on the following tasks: progressive ratio, simple discrimination, simple reversal and the intra- and extra-dimensional set-shifting tasks. Therefore in addition to rhesus macaques and common marmosets, the baboon is a suitable nonhuman primate to study cognitive function using the same neuropsychological tasks as those used in humans. Because the baboon is widely investigated to determine growth, endocrine and neurological function at various stages of the life cycle, especially development, the methods we have evaluated in detail here should prove of use in combining the power of behavioral studies with investigations of development of different systems (growth, endocrine, cardiovascular) in the same subjects. Future studies will employ this behavioral approach to offspring treated prenatally with betamethasone or nutrient restricted during gestation, which will provide important information for translation to the etiology of human disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Christopher Pryce and Ralf Wimmer for their advice and assistance in performing this study.

Supported by: HD057480-01A1 and HD 21350-17 supplement for JR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baxter MG, Gaffan D. Asymmetry of attentional set in rhesus monkeys learning colour and shape discriminations. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Colchester. ) 2007;60:1–8. doi: 10.1080/17470210600971485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield RL, Gendle MH, Cory-Slechta DA. Impaired neuropsychological functioning in lead-exposed children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2004;26:513–540. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2601_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AM. Animal models of human placentation--a review. Placenta. 2007;28(Suppl A):S41–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P, Roberts AC, Dias R, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Perseveration and strategy in a novel spatial self-ordered sequencing task for nonhuman primates: effects of excitotoxic lesions and dopamine depletions of the prefrontal cortex. J. Cogn Neurosci. 1998;10:332–354. doi: 10.1162/089892998562771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LA, Nijland MJ, Gilbert JS, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, McDonald TJ, Shade RE, Nathanielsz PW. Effect of 30 per cent maternal nutrient restriction from 0.16 to 0.5 gestation on fetal baboon kidney gene expression. J. Physiol. 2006a;572:67–85. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LA, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Hubbard GB, Nijland MJ, McDonald TJ, Nathanielsz PW. Gene expression profile differences in left and right liver lobes from mid-gestation fetal baboons: a cautionary tale. J. Physiol. 2006b;572:59–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts HS, Muggleton NG, Bowditch AP, Pearce PC, Nutt DJ, Scott EA. Home cage presentation of complex discrimination tasks to marmosets and rhesus monkeys. Lab Anim. 1999;33:207–214. doi: 10.1258/002367799780578174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decamp E, Schneider JS. Attention and executive function deficits in chronic low-dose MPTP-treated non-human primates. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:1371–1378. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decamp E, Schneider JS. Effects of nicotinic therapies on attention and executive functions in chronic low-dose MPTP-treated monkeys. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24:2098–2104. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociation in prefrontal cortex of affective and attentional shifts. Nature. 1996;380:69–72. doi: 10.1038/380069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociable forms of inhibitory control within prefrontal cortex with an analog of the Wisconsin Card Sort Test: restriction to novel situations and independence from “on-line” processing. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:9285–9297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09285.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorion AA, Duyme M, Zanca M, Dubois B, Beau J. Relationship between discrimination tasks of the cantab and the corpus callosum morphology in Alzheimer’s disease. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2001;92:1205–1210. doi: 10.2466/pms.2001.92.3c.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman DM, Coelho AM, Jr., Carey KD, Bramblett CA. Weight growth in savannah baboons: a longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Growth. 1984;48:425–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub MS. Cognitive testing (delayed non-match to sample) during oral treatment of female adolescent monkeys with the estrogenic pesticide methoxychlor. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazbec S, Pantelis C, Robbins T, Weickert T, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE. Intra-dimensional/extra-dimensional set-shifting performance in schizophrenia: impact of distractors. Schizophr. Res. 2007;89:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levaux MN, Potvin S, Sepehry AA, Sablier J, Mendrek A, Stip E. Computerized assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: promises and pitfalls of CANTAB. Eur. Psychiatry. 2007;22:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Levitz M, Hubbard GB, Jenkins SL, Han V, Ferry RJ, Jr., McDonald TJ, Nathanielsz PW, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE. The IGF axis in baboon pregnancy: placental and systemic responses to feeding 70% global ad libitum diet. Placenta. 2007;28:1200–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M. Practitioner review: computerized assessment of neuropsychological function in children: clinical and research applications of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery (CANTAB) J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2003;44:649–663. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirdy J, Sussmann JE, Hall J, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC, McIntosh AM. Set shifting and reversal learning in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2009;39:1289–1293. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medin DL. Measuring and training dimensional preferences. Child Dev. 1973;44:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. Impairment in abstraction and set shifting in aged rhesus monkeys. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. A non-human primate test of abstraction and set shifting: an automated adaptation of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2005;146:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggleton NG, Smith AJ, Scott EA, Wilson SJ, Pearce PC. A long-term study of the effects of diazinon on sleep, the electrocorticogram and cognitive behaviour in common marmosets. J. Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:455–466. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara AH, Bernot T, Tuszynski MH. Age-related cognitive deficits in rhesus monkeys mirror human deficits on an automated test battery. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijland MJ, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Nathanielsz PW, Cox LA. Non-human primate fetal kidney transcriptome analysis indicates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a central nutrient-responsive pathway. J. Physiol. 2007;579:643–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Cook I, Coon H, Dawson G, Joseph RM, Klin A, McMahon WM, Minshew N, Munson JA, Pennington BF, Rogers SJ, Spence MA, Tager-Flusberg H, Volkmar FR, Wrathall D. Performance on Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery subtests sensitive to frontal lobe function in people with autistic disorder: evidence from the Collaborative Programs of Excellence in Autism network. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004;34:139–150. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022605.81989.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce PC, Crofts HS, Muggleton NG, Scott EA. Concurrent monitoring of EEG and performance in the common marmoset: a methodological approach. Physiol Behav. 1998;63:591–599. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Actions of placental and fetal adrenal steroid hormones in primate pregnancy. Endocr. Rev. 1995;16:608–648. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-5-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SM, Coghill DR, Matthews K. Neuropsychological functioning in stimulant-naive boys with hyperkinetic disorder. Psychol. Med. 2005;35:1109–1120. doi: 10.1017/s0033291705004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Semple J, Kumar R, Truman MI, Shorter J, Ferraro A, Fox B, McKay G, Matthews K. Effects of scopolamine on delayed-matching-to-sample and paired associates tests of visual memory and learning in human subjects: comparison with diazepam and implications for dementia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;134:95–106. doi: 10.1007/s002130050430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC. Comparison of cognitive function in human and non-human primates. Brain Res. Cogn Brain Res. 1996;3:319–327. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(96)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. The effects of intradimensional and extradimensional shifts on visual discrimination learning in humans and non-human primates. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. B. 1988;40:321–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hodara VL, Parodi LM, Hubbard GB, Jenkins SL, Dudley DJ, Nathanielsz PW, Giavedoni LD. Three weekly courses of betamethasone administered to pregnant baboons at 0.6, 0.65, and 0.7 of gestation alter fetal and maternal lymphocyte populations at 0.95 of gestation. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2006;69:149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Lopez-Alvarenga JC, Comuzzie AG, Miller MM, Ford SP, Li C, Hubbard GB, Ferry RJ, Jr., Nathanielsz PW. The prolonged effect of repeated maternal glucocorticoid exposure on the maternal and fetal leptin/insulin-like growth factor axis in Papio species. Reprod. Sci. 2009;16:308–319. doi: 10.1177/1933719108325755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittmann VD, Visser I, Raijmakers ME. Multiple learning modes in the development of performance on a rule-based category-learning task. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2079–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, Pearce P, Fairhall S, Muggleton N, Smith J. Training nonhuman primates to cooperate with scientific procedures in applied biomedical research. J. Appl. Anim Welf. Sci. 2003;6:199–207. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli S, Pennanen L, Dettling AC, Feldon J, Higgins GA, Pryce CR. Performance of the marmoset monkey on computerized tasks of attention and working memory. Brain Res. Cogn Brain Res. 2004;19:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffe MA, Weed MR, Gold LH. Scopolamine alters rhesus monkey performance on a novel neuropsychological test battery. Brain Res. Cogn Brain Res. 1999;8:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(99)00021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytko ML, Murray R, Higgs CJ. Executive function and attention are preserved in older surgically menopausal monkeys receiving estrogen or estrogen plus progesterone. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:10362–10370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1591-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed MR, Bryant R, Perry S. Cognitive development in macaques: attentional set-shifting in juvenile and adult rhesus monkeys. Neuroscience. 2008;157:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed MR, Taffe MA, Polis I, Roberts AC, Robbins TW, Koob GF, Bloom FE, Gold LH. Performance norms for a rhesus monkey neuropsychological testing battery: acquisition and long-term performance. Brain Res. Cogn Brain Res. 1999;8:185–201. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]