Abstract

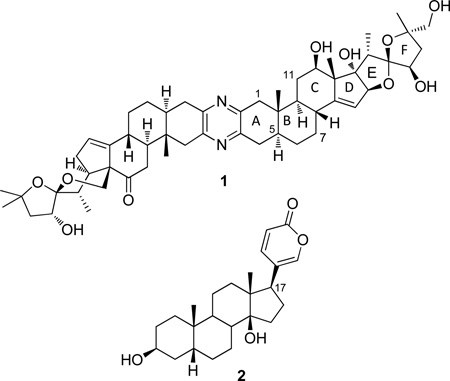

Cephalostatin 1 (1), a remarkably strong cancer cell growth inhibitory trisdecacyclic, bis-steroidal pyrazine isolated from the marine tube worm Cephalodiscus gilchristi, continues to be an important target for practical total syntheses and a model for the discovery of less complex structural modifications with promising antineoplastic activity. In the present study, the cephalostatin E and F rings were greatly simplified by replacement at C-17 with an α-pyrone (in 12), typical of the steroidal bufodienolides, and by a dihydro-γ-pyrone (in 16). The synthesis of pyrazine 12 from 5α-dihydrotestosterone (nine steps, 8% overall yield) provided the first route to a bis-bufadienolide pyrazine. Dihydro-γ-pyrone 16 was synthesized in eight steps from ketone 13. While only insignificant cancer cell growth inhibitory activity was found for pyrones 12 and 16, the results provided further support for the necessity of more closely approximating the natural D–F ring system of cephalostatin 1 in order to obtain potent antineoplastic activity.

The isolation and structure of cephalostatin 1 (1), a powerful anticancer constituent of the Indian Ocean colonial marine tube worm Cephalodiscus gilchristi Ridewood (Cephalodiscidae), was summarized by us2a 24 years ago. Subsequently, 1 became the prototype of the cephalostatins2 and ritterazines, which together make up a unique family of 45 highly oxygenated bis-steroidal pyrazines.3 These marine invertebrate constituents exhibit powerful cancer cell growth inhibitory behavior (e.g., murine P388 lymphocytic leukemia cell line, ED50 10−7 µg/mL; NCI 60 human cancer cell lines, GI50 1.8 nM).2 The availability of the cephalostatins and ritterazines from their only known natural sources, C. gilchristi and the marine tunicate Ritterella tokioka, is still extremely limited. As a result, in vivo anticancer evaluation of these very promising natural products and subsequent preclinical development has been greatly restricted.

The outstanding antineoplastic potency together with the new and challenging molecular architecture of 1 and poor availability from natural sources (~ 10−6% yields from C. gilchristi) soon led to synthetic approaches by a number of research groups. By 1998, Fuchs and colleagues had completed the first total synthesis of 1 (in 65 synthetic steps)4a and of two additional members of the cephalostatin family (7 and 12) and ritterazine K.4b However, owing to the complexity of the targets only very small amounts of these substances were produced and in very low overall yields (2 mg of 1, 10−5%, for instance),4a not suitable to supply sufficient samples at reasonable cost for extended biological evaluation. However, the recent enantioselective total synthesis of cephalostatin 1 by Shair3c does offer a potentially useful approach to scale-up and represents a splendid contribution. Meanwhile, a number of SAR studies concerned with the cephalostatins were initiated by various research groups in an effort to discover the minimum pharmacophore required to maintain potent cancer cell growth inhibitory behavior.5,6

The urgency of the practical syntheses and structural simplification endeavor was elevated when Vollmar and colleagues3e,7 began to elucidate the unique mechanism of cephalostatin 1 (1). Because of their detailed research results, it is clear that 1 evokes a new cytochrome c-independent apoptosis signaling pathway. This is in contrast to most of the well-known anticancer drugs, which act in a cytochrome c-dependent route.3e,7b–d The lack of cytochrome c release by 1 indicates that it induces aopotosis in cancer cells via caspase-9 activation without formation of an apoptosome (complex of cytochrome c, procaspase-9 and the cytosolic factor Apaf-1). As part of this unique apoptosis mechanism,7 1 has been found to selectively release mitochondrial Smac (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases), necessary for caspase-9 and caspase-2 activations.7a Furthermore, 1 produces an endoplasmic reticulum stress response, inducing caspase-4, which activates the caspase-9 route to apoptosis. The new pathway is marked by structural changes in the mitochondria.7b Current research results7a strongly indicate that the action of 1 on cancer cells is very complex and that further mechanistic investigation will provide many new insights of importance to cancer biology and further preclinical development of the cephalostatins. Shair and colleagues3a have recently reported that cephalostatin 1 (1) is one of a group of molecules that target oxysterol binding protein and its closest paralog and are useful as probes to reveal the functions of these proteins.

In order to extend our SAR studies1 of 1, we next focused on examining an extension of the C-17 side chain of a bis-steroidal pyrazine with a 5-substituted α-pyrone system characteristic of the bufadienolides, a large family of broadly bioactive animal and plant steroids originally isolated from toad venom. Certain members of the bufadienolides possess significant antineoplastic behavior,8 typified by bufalin (2),8b–d and a broad spectrum of other biological activities, including regulation of hypertension.8e–f Also, in an effort to keep synthetic complexity to a minimum, a symmetrical C-17-pyrone bis-steroidal pyrazine was targeted. Cephalostatin 122f is the only natural C2-symmetric cephalostatin.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

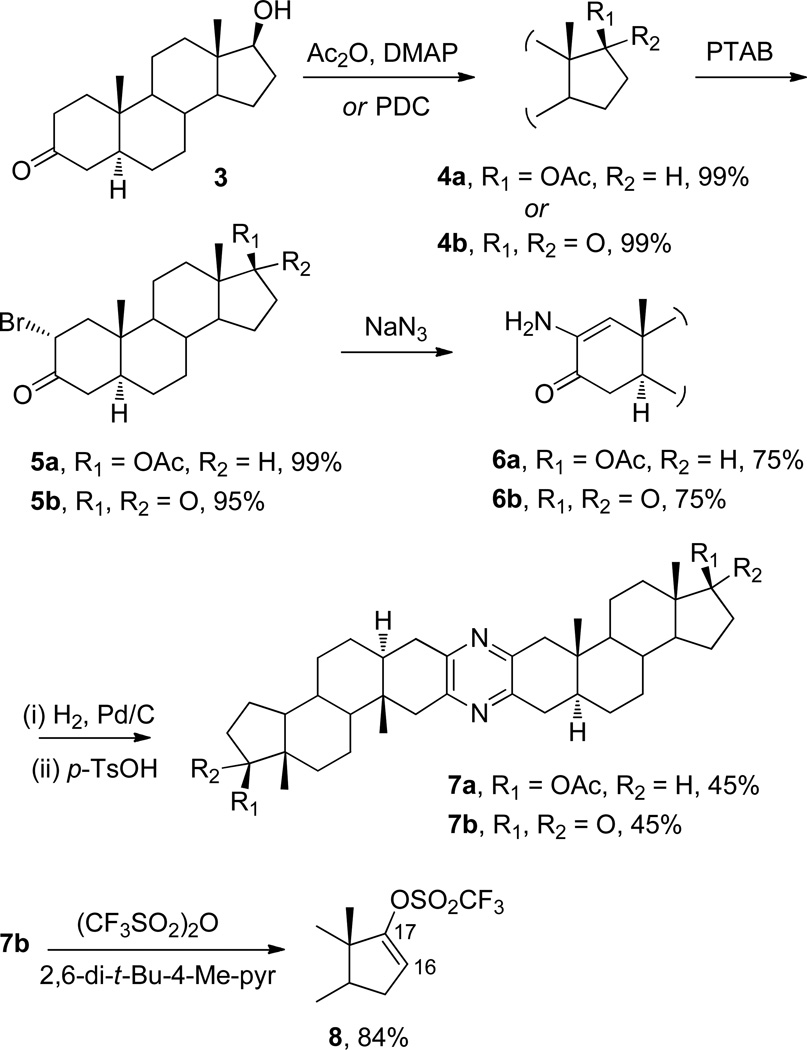

Initial efforts (Scheme 1)9 were directed at the formation of a simple symmetric pyrazine derived from 3-oxo-17β-hydroxy-5α-androstane (3, 5α-dihydrotestosterone) that would be suitable for condensation with the required pyran-2-one synthon, according to the method of Liu and Meinwald.10 Acylation of 3 afforded 4a, and subsequent conversion of 4a to 5a employing phenyltrimethylammonium tribromide (PTAB)9e was readily accomplished (98% yield from 3). Transformation of 5a to 6a with NaN39c,d and catalytic NaI9f in dimethylformamide (DMF) proceeded well (75% yield). Direct dimerization of 6a to give symmetric pyrazine 7a was attempted with p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TsOH)9b,c as catalyst, but a dehydro-pyrazine was formed instead. Subsequent attempts at conversion to 7a with O2 and again with 10% Pd/C proved ineffective. Hence, an alternate route was chosen in which 6a was first reduced catalytically with H2 and 10% Pd/C in toluene at 40 psi for 2 h.10 Subsequent acid-catalyzed dimerization with p-TsOH in EtOH provided 7a in moderate yield (45%), with an overall yield of 32% from 3.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 17,17′-diacetate 7a and 17,17′-diketone 7b from 3-oxo-17β-hydroxy-5α-androstane (3)

Rather than use 7a as a substrate to obtain the required 17-oxo derivative, it was more practical to repeat the sequence depicted in Scheme 1 with 3,17-dioxo-5α-androstane (4b) as starting material, which was prepared by oxidation of 3 using pyridinium dichromate (PDC). Subsequent bromination to afford 5b, followed by amination (6b) and dimerization, yielded 17,17′-dioxopyrazine 7b in five steps from 3 in an overall yield of 28%. Efforts at transformation of ketone 7b to 16,16′-dienyl-17,17′-ditriflate 8 using lithium diisopropylamide (LDA)10 as base resulted in decomposition, but the hindered base 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine proved very effective as a substitute for LDA in promoting the enolization of 7b, which provided 8 in good yield (84%) as a substrate for subsequent condensation with a trimethylstannyl derivative.

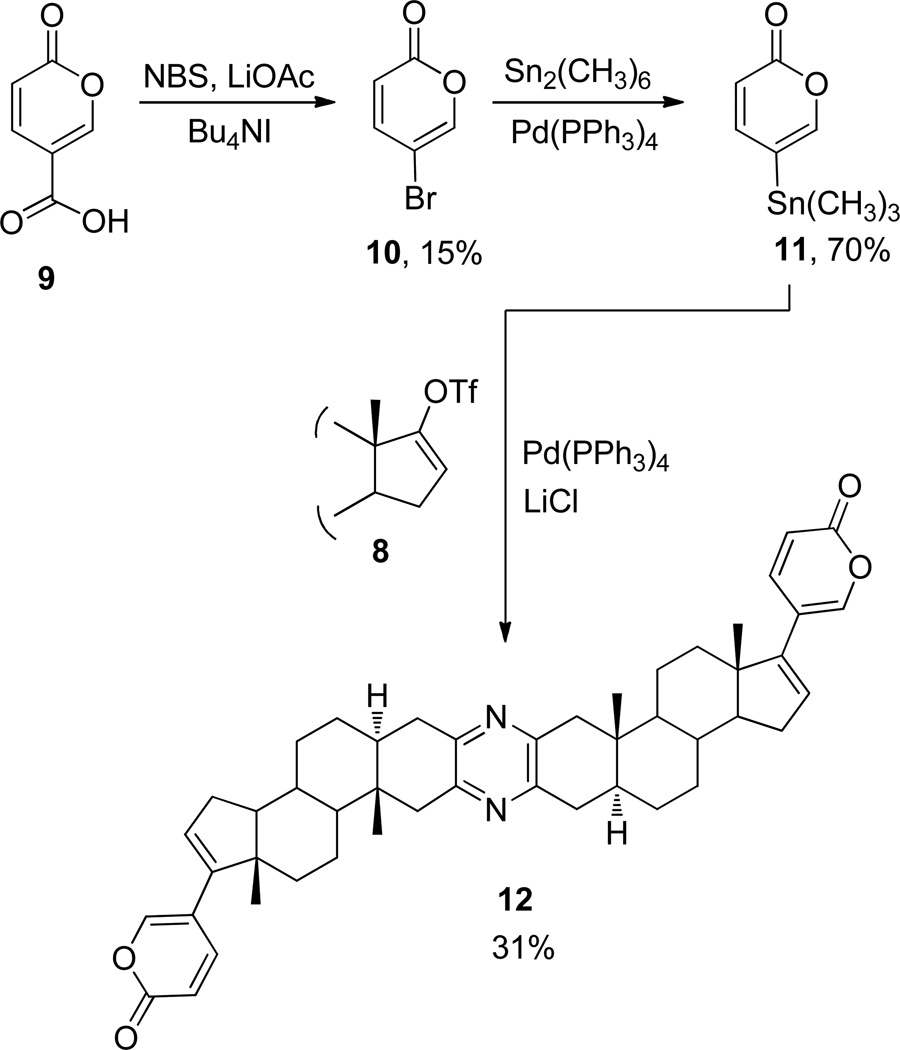

Adaptation of the sequence detailed by Cho11 for decarboxylation/bromination of coumalic acid (9, Scheme 2) with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and lithium acetate led to 5-bromo-2H-pyran-2-one (10) in low yield (15%), accompanied by a dibrominated byproduct that was obtained in similar yield. By employment of methods analogous to those used to give phenylstannates, as described by Liu and Meinwald,10 treatment of 10 with hexamethylditin and the catalyst Pd(PPh3)4 yielded 5-(trimethylstannyl)-2H-pyran-2-one (11) in good yield (70%). Stille coupling12 of enol triflate 8 and stannyl pyrone 11 employing Pd(PPh3)4 as catalyst resulted in the first synthesis (31% yield) of a bis-bufadienolide pyrazine (12), which was obtained from 3 in 8% overall yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of bis-bufadienolidepyrazine 12

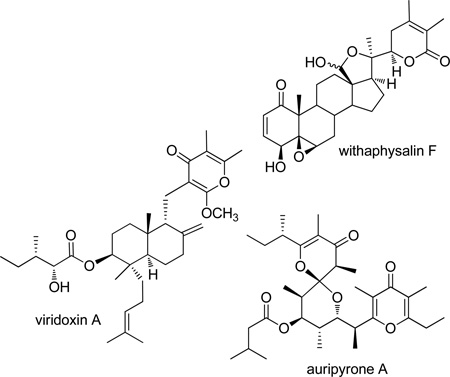

In order to extend the bis-steroidal pyrazine 17-pyrone SAR probes, the general approach was extended as follows to a dihydro-γ-pyrone. The rationale for a dihydro-α- or γ-pyrone unit at or near the steroid C-17 position receives some support from nature. A cancer cell growth inhibitory series of terrestrial plant constituents that contain a dihydro-α-pyrone ring incorporated at the steroid C-22 position, known as the withaphysalins, of which withaphysalin F13a (from Physalis angulata) is illustrative, are found in the Solanaceae family. Biologically active γ-pyrone-based natural products have been isolated from plant, fungal and animal sources (e.g., viridoxin A13b from the fungus Metarhizium flavoviride and auripyrone A13c from the mollusk Dolabella auricularia), and interest in the properties of the widespread γ-pyrones has increased recently.13d,e

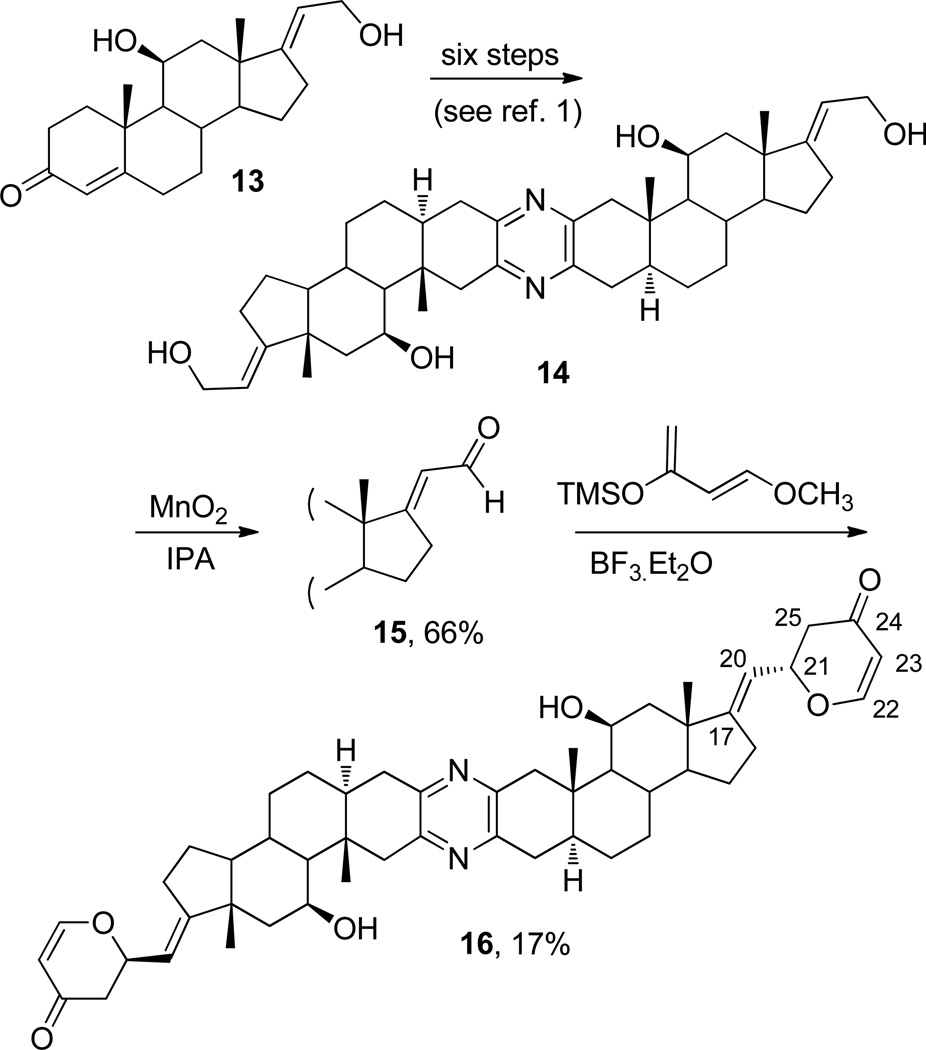

In the next approach to formation of a cephalostatin analogue with a structurally very simple replacement for the E and F rings of 1, that is, a dihydro-γ-pyrone unit, we utilized pyrazine 14 (prepared in six synthetic steps from keto-alcohol 13 as described in our previous report,1 which was focused on replacement of the E and F rings with a rhamnoside). Selective oxidation (Scheme 3) of 14 with manganese dioxide afforded dialdehyde 15. Condensation of 15 with Danishefsky’s diene14 employing a Diels-Alder-type cycloaddition provided, albeit in low yield (17%), the 2,3-dihydro-4-pyrone 16. The configuration at C-21 on the pyrone rings was deduced from analysis of the 1H and 1H-1H COSY NMR spectra. A pair of doublets at δ 7.38 (J = 6.0 Hz) and at δ 7.35 (J = 6.0 Hz), which were assigned to the C-22 protons of the rings, were coupled with the signal at δ 5.42 (J = 6.0 Hz, H-23). The multiplet at δ 5.20 (H-20) shows a vicinal coupling of 8.5 Hz and an allylic coupling of 2.5 Hz, corresponding to a strong correlation with the multiplet at δ 4.95 – 5.03 (H-21) and a minor correlation with the signal at δ 2.53 – 2.68 (H-25). These data are consistent with a structure that includes both (R-) and (S)-pyrone substituents, resulting from both exo and endo hetero-Diels–Alder cycloaddition, which gives rise to complex multiplets for each of the C-20 and C-21 protons and a pair of doublets for the two C-22 protons. The signals from the C-23 protons are coincident, and those from H-25 are buried in the steroid skeleton signals.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of dihydro-4-pyrone 16 from 13

Compounds 7a,b, 8, 12, and 16 were screened for cancer cell growth inhibitory activity in the murine P388 lymphocytic leukemia cancer cell line (Table 1). The steroidal pyrazine side-chain pyrones 12 (ED50 41 µg/mL, 57 µM) and 16 (ED50 20 µg/mL, 25 µM) did not exhibit significant (ED50 ≤ 10 µg/mL) activity. However, these SAR results added further confirmation of Winterfeldt’s6c–f early analysis of cephalostatin 1 structural requirements for strong cancer cell growth inhibitory activity, particularly with respect to the need for a C-14 double bond, C-12 oxygenation (alcohol or ketone), and a 17α-hydroxy group for optimum activity. Presumably, there are a number of other less obvious molecular features of the cephalostatin-type steroids that are critical to their quite unique potency against cancer cell growth and mechanisms of biological activity. The uncovering of such structural features is a goal of future SAR investigations of the cephalostatins. Meanwhile, we are further evaluating the bis-steroidal pyrazine pyrones described herein for other biological activities.

Table 1.

Murine P388 Lymphocytic Leukemia Cell Line Results (ED50 values)

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures

Melting points are uncorrected and were determined with an Electrothermal 9100 apparatus. The IR spectra were obtained using a Thermo-Nicolet (Thermo Fisher Scientific) Avatar 360 Series FT-IR spectrometer. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded employing Varian Gemini 300 and Varian Unity 500 instruments using CDCl3 (TMS internal reference) as solvent unless otherwise noted. Bs refers to broad singlet. High resolution APCI+ (atmospheric pressure chemical ionization) mass spectra were obtained with a Jeol JMS-LCmate mass spectrometer. Elemental analyses were determined by Galbraith Laboratories, Inc.

Ether refers to diethyl ether, TEA to triethylamine, DCM to dichloromethane, DMAP to 4-dimethylaminopyridine, Ar to argon gas, and rt to room temperature. All solvents were redistilled. All chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich Corp. or Acros Organics (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using Analtech silica gel GHLF Uniplates and were visualized with either phosphomolybdic acid (10% wt/wt solution in EtOH) or iodine. Solvent extracts of aqueous solutions were dried over anhydrous magnesium or sodium sulfate. Where appropriate, the crude products were purified by column chromatography (CC) on silica gel (70–230 mesh ASTM) from E. Merck.

3-Oxo-17β-acetoxy-5α-androstane (4a)

To a stirred solution of dihydrotestosterone (3, 1.0 g, 3.45 mmol) and DMAP (cat) in pyridine (10 mL) at rt under Ar was added acetic anhydride (10 mL, 106 mmol) dropwise, and stirring continued for 6 h. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C, H2O (15 mL) and ether (15 mL) were added, and the phases were separated. After extraction of the aqueous phase with ether (2 × 15 mL), the combined organic phase was washed with HCl (1 M, 2 × 15 mL), NaHCO3 (sat. aq., 2 × 15 mL), and H2O (15 mL). After drying, concentration of the organic phase afforded a colorless amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone provided 4a as colorless crystals (1.14 g, 99%): mp 155–156 °C [lit15 mp 157–158.5 °C]; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3,) δ 4.60 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H-17α), 2.42 (1H, m, H-2α), 2.32 (1H, t, J = 9.0 Hz, H-2β), 2.21 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H-4α), 2.10 (1H, m, H-16β), 2.04 (1H, m, H-4β), 2.03 (3H, s, -OCOCH3), 1.75–1.05 (14H), 1.02 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (1H, m), 0.81 (3H, s, CH3), 0.76 (1H, m); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 211.8, 171.2, 82.7, 53.7, 50.6, 49.6, 44.6, 42.6, 38.5, 38.1, 36.8, 35.7, 35.2, 31.2, 28.8, 27.5, 23.5, 21.1, 20.9, 12.1, 11.4; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 333.24144 [M + H]+ (calcd for C21H33O3, 333.24297); anal. C 75.76, H 9.89%, calcd for C21H32O3, C 75.86, H 9.70%.

2α-Bromo-3-oxo-17β-acetoxy-5α-androstane (5a)

To a stirred solution of 4a (0.50 g, 1.50 mmol) in THF (5 mL) at 0 °C under Ar was added phenyltrimethylammonium tribromide (PTAB, 0.59 g, 1.56 mmol), and the solution immediately turned orange. After 20 min stirring, a tan precipitate formed, which dissolved upon addition of H2O (5 mL). After extraction with DCM (2 × 5 mL) the combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in minimal DCM, and subjected to CC (3:7 EtOAc–n-hexane) to yield a light tan amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone gave 5a as colorless crystals (0.61 g, 99%): mp 171.8–172.4 °C; IR (neat) νmax 1733 (C=O, ketone and ester) cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.73 (1H, q, J = 8.8 Hz, H-2β), 4.58 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H-17α), 2.64 (1H, q, J = 8.8 Hz, H-1α), 2.42 (2H, m, H-4α,β), 2.17 (1H, m, H-16β), 2.03 (3H, s, OCOCH3), 1.80 (1H), 1.78–1.20 (14H), 1.08 (3H, s, CH3), 0.98 (1H, m), 0.85 (1H, m), 0.79 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.9, 171.1, 82.5, 54.3, 53.5, 51.6, 50.4, 47.4, 43.8, 42.6, 39.0, 36.6, 34.7, 31.0, 28.2, 27.5, 23.5, 21.1, 21.0, 12.1; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 411.15272 [M + H]+ (calcd for C21H32 79BrO3, 411.15348); anal. C 61.42, H 7.56%, calcd for C21H31BrO3, C 61.37, H 7.60%.

2-Amino-3-oxo-17β-acetoxy-5α-androstan-1-ene (6a)

To a stirred solution of 5a (0.50 g, 1.22 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) at rt under Ar was added NaN3 (1.00 g, 15.4 mmol) and NaI (cat). The suspension was heated to 60 °C for 2 h and then cooled to rt, H2O (10 mL) was added, and the solution was extracted with ether (5 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, and separation (CC, 1% TEA in 7:3 n-hexane–EtOAc) yielded a yellow amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone gave 6a as light yellow needles (0.46 g, 75%): mp 149.8–150.5 °C; IR (neat) νmax 1739, 1715 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.09 (1H, s, H-1), 4.61 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H-17α), 3.43 (2H, bs, NH2), 2.41 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H-4α), 2.26 (1H, dd, J = 8.8 Hz, H-4β), 2.16 (1H, m, H-16β), 2.04 (3H, s, OCOCH3), 1.91 (1H, m, H-5α), 1.80–1.20 (14H), 1.08 (3H, s, CH3), 0.98 (1H, m), 0.85 (1H, m), 0.79 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 195.7, 171.7, 137.7, 126.5, 82.6, 51.2, 50.7, 44.8, 42.8, 40.2 (C-4), 38.1, 36.8, 35.3, 30.9, 27.5, 27.2, 27.1, 23.4, 21.1, 20.9, 13.9, 12.2; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 346.23829 [M + H]+ (calcd for C21H32NO3, 346.23822); anal. C 73.32, H 9.11%, calcd for C21H31NO3, C 73.01, H 9.04%.

Bis(17β-acetoxy-5α-androstan[3,2-e,3’,2’])pyrazine (7a)

To a stirred solution of amine 6a (0.50 g, 1.66 mmol) in toluene (10 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (0.28 g, 15 mol % Pd) in a heavy-walled hydrogenation flask. The flask was purged with H2 (4 ×) before hydrogenation at 40 psi for 2 h. The black suspension was collected by filtration and washed with DCM (10 mL), and concentration of the organic phase in vacuo provided the 2α-aminoketone3b,9a,b intermediate as a brown solid, which was immediately used for dimerization without further purification. The 2α-aminoketone was dissolved in EtOH (5 mL), and pTsOH (cat) was added. After stirring for 48 h, the reaction solution was filtered through a pad of silica gel and washed with EtOAc (100 mL). The organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, and fractionation (CC, 1% TEA in 7:3 n-hexane–EtOAc) yielded an amorphous solid. Cystallization from cyclohexane–acetone provided 7a as colorless needles (0.24 g, 45%): mp 240 °C (dec); IR (neat) νmax 1738, 1717 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.61 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H-17α), 2.91 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-1α), 2.71 (1H, dd, H-4α), 2.55 (2H, m, H-1β, H–4β), 2.16 (1H, m, H–16β), 2.04 (3H, s, OCOCH3), 1.81–1.20 (14H), 1.08 (3H, s, CH3), 0.98 (1H, m), 0.85 (1H, m), 0.79 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.2, 133.6, 127.1, 82.7, 52.0, 50.8, 50.6, 43.5, 42.8, 42.5, 41.7, 39.9, 38.3, 36.9, 35.6, 35.4, 30.9, 27.5, 27.0, 23.5, 21.2, 21.1; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 657.46041 [M + H]+ (calcd for C42H61N2O4, 657.46313); anal. C 76.94, H 9.11, N 4.31%, calcd for C42H60N2O4, C 76.79, H 9.21, N 4.26%.

3,17-Dioxo-5α-androstane (4b)

To a stirred solution of dihydrotestosterone (3, 1.0 g, 3.44 mmol) in DCM (10 mL) at rt under Ar was added pyridinium dichromate (PDC, 2.10 g, 5.58 mmol). After stirring for 2 h, the black suspension was collected by vacuum filtration through a short pad of silica gel with EtOAc (100 mL) as eluent. The organic extract was concentrated in vacuo, and purification (CC, 3:2 n-hexane–EtOAc) led to a colorless, amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone provided 4b as colorless crystals (0.98 g, 99%): mp 134.1–134.5 °C [lit16 mp 133.5–134.0 °C]; IR (neat) νmax 1742, 1739 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.42 (1H, m, H–2α), 2.32 (1H, t, J = 9.0 Hz, H–2β), 2.21 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, H–4α), 2.10 (1H, m, H–16β), 2.04 (1H, m, H–4β), 1.82 (1H, m, H–16α), 1.76–1.11 (14H), 1.03 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (1H, m), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.76 (1H, m); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 220.9 (C-17), 210.9 (C-3), 53.4, 50.7, 47.2, 46.1, 44.0, 37.9, 37.5, 35.3, 34.5, 31.0, 30.0, 28.1, 21.2, 20.2, 13.3, 10.9; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 289.2165 [M + H]+ (calcd for C19H29O2, 289.2168); anal. C 79.28, H 9.95%, calcd for C19H28O2, C 79.12, H 9.78%.

2α-Bromo-3,17-dioxo-5α-androstane (5b)

To a stirred solution of 4b (1.5 g, 5.20 mmol) in THF (15 mL) at 0 °C under Ar was added PTAB (2.20 g, 5.85 mmol). The solution immediately turned orange and was stirred for 20 min. A tan precipitate formed that dissolved on addition of H2O (10 mL). After extraction with DCM (2 × 15 mL), the combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, and purification (CC, 7:3 n-hexane–EtOAc) yielded a light tan amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone gave 5b as colorless crystals (1.81 g, 95%): mp 136.4–136.7 °C; IR (neat) νmax 1733, 1716 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.73 (1H, q, J = 8.8 Hz, H–2β), 2.65 (1H, q, J = 8.8 Hz, H–1β), 2.45 (3H, m, H–4α, H–16β, H–16α), 2.11 (1H, t, H–1α), 1.96 (1H), 1.89–1.18 (14H), 1.11 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (1H, m), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.76 (1H, m); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 220.9 (C-17), 211.1 (C-3), 54.3 (C-2), 53.5, 53.2, 51.0, 50.5, 47.1, 46.9, 43.3, 35.2, 34.0, 30.1, 29.8, 27.6, 21.2, 20.3, 17.2, 13.3, 11.6; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 367.1321 [M + H]+ (calcd for C19H28 79BrO2 367.1273); anal. C 62.21, H 7.39%, calcd for C19H27BrO2, C 62.13, H 7.41%.

2-Amino-3,17-dioxo-5α-androstan-1-ene (6b)

To a stirred solution of 5b (1.5 g, 4.08 mmol) in DMF (15 mL) at rt under Ar was added NaN3 (2.70 g, 41.5 mmol) and NaI (cat), and the suspension was heated to 60 °C for 2 h. After cooling to rt, the mixture was diluted with H2O (15 mL) and extracted with ether (5 × 20 ml). The combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was purified (CC, 1% TEA in 7:3 n-hexane–EtOAc) to yield a yellow amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone gave 6b as light yellow needles (0.92 g, 75%): mp 135.3–175.9 °C; IR (neat) νmax 1734, 1700 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.07 (1H, s, H-1), 3.45 (2H, bs, NH2), 2.45 (3H, m, H–4α, H–16β, H–16α), 2.11 (1H, H–16β), 1.94–1.16 (14H), 1.00 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (1H, m), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.76 (1H, m); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 220.1 (C-17), 195.0 (C-3), 137.4 (C-1), 125.4 (C-2), 50.9, 50.8, 47.3, 44.3, 39.6, 37.7, 35.3, 34.6, 31.0, 29.7, 26.6, 21.1, 20.2, 13.4, 11.9; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 302.2120 [M + H]+ (calcd for C19H28NO2, 302.2120); anal. C 75.42, H 9.13, N 4.56%, calcd for C19H27NO2, C 75.71, H 9.03, N 4.65%.

Bis(17-oxo-5α-androstan[2,3-b:2′ ,3′-e])pyrazine (7b)

To a stirred solution of 6b (0.50 g, 1.66 mmol) in toluene (10 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (0.28 g, 15 mol % Pd) in a heavy-walled hydrogenation flask. The flask was purged with H2 (4×) before hydrogenation at 40 psi for 2 h. The black suspension was then removed by filtration and washed with DCM (10 mL). The combined organic extract was concentrated in vacuo to yield the 2α-aminoketone intermediate as a brown solid, which was immediately used without further purification for dimerization. The amine (1.66 mmol) was dissolved in EtOH (5 mL) and pTsOH (cat) added. After stirring for 48 h, the reaction solution was filtered (vacuum) through a short pad of silica gel and washed with EtOAc (100 mL). The solvent extract was concentrated in vacuo, adsorbed onto silica gel, and subjected to CC (7:3 n-hexane–EtOAc, 1% TEA) to give an amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone provided 7b as colorless needles (0.19 g, 45%): mp 235 °C (dec); IR (neat) νmax 1737 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.93 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H–1α), 2.68 (1H, dd, H–4α), 2.50 (3H, m, H–1β, H–4β, H–16β), 2.19 (1H, m, H–16α), 1.88–0.96 (16H), 0.88 (3H, s, CH3), 0.85 (1H, m), 0.82 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 220.4 (C-17), 133.6 (C-2), 127.1 (C-3), 53.3, 50.8, 47.1, 45.4, 41.9, 41.3, 35.3, 34.9, 34.4, 33.3, 32.6, 31.1, 29.9, 27.6, 24.2, 21.3, 20.0, 13.2, 11.5; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 569.4158 [M + H]+ (calcd for C38H53N2O2, 569.4107); anal. C 80.31, H 9.11, N 4.86%, calcd for C38H52N2O2, C 80.24, H 9.21, N 4.92%.

Bis(17-triflyloxy-Δ16–5α–androstan[2,3-b:2′ ,3′-e])pyrazine (8)

To a stirred solution of 7b (0.40 g, 0.70 mmol) and 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine (0.44 g, 2.14 mmol) in DCM (4 mL) at −10 °C under Ar was added (dropwise) triflic anhydride (0.36 mL, 2.14 mmol). After 18 h, H2O (8 mL) and DCM (4 mL) were added, and the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (2 × 8 mL). The combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, and silica gel separation (CC, 1:1 n-hexane–EtOAc) yielded 8 as an amorphous light yellow solid (0.49 g, 84%): mp 190 °C (dec); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.77 (1H, m, H-16), 2.91 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H–1α), 2.71 (1H, dd, H–4α), 2.50 (2H, m, H–1β, H–4β), 1.81–1.11 (16H), 1.00 (3H, s, CH3), 0.94 (1H, m), 0.84 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 158.7 (C-17), 152.0 (OSO2CF3), 135.6 (C-2), 129.1 (C-3), 113.9 (C-16), 53.6, 53.5, 45.1, 44.3, 41.4, 35.3, 34.9, 32.8, 32.2, 29.9, 29.6, 28.0, 27.5, 19.9, 14.7, 11.4; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 833.3094 [M + H]+ (calcd for C40H51F6N2O6S2, 833.3093).

5-Bromo-2H-pyran-2-one (10)

To a stirred solution of coumalic acid (9, 10.0 g, 71.4 mmol) in CH3CN–H2O (9:1; 400 mL) at rt was added LiOAc (5.60 g, 84.9 mmol), NBS (19.0 g, 107 mmol) and Bu4NI (1.0 g, 4 mol %). After the mixture stirred for 10 days, H2O (250 mL) and DCM (250 mL) were added, and the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (2 × 100 mL). The combined solvent extract was concentrated in vacuo, and separation of the residue (CC, 9:1 n-hexane–EtOAc) led to 10 as a light tan crystalline solid (1.9 g, 15%); mp 39.4–39.9 °C; IR (neat) νmax 1738 cm−1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 7.63 (1H, dd, J = 2.7, 1.2 Hz, H-6), 7.32 (1H, dd, J = 9.9, 2.7 Hz, H-4), 6.28 (1H, dd, J = 1.2, 9.9 Hz, H-3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 126 MHz) δ 171.0 (C-2), 146.7 (C-4), 133.8 (C-6), 120.9 (C-3), 100.6 (C-5).

5-(Trimethylstannyl)-2H-pyran-2-one (11).10

To a stirred solution of pyrone 10 (0.70 g, 4.00 mmol) in THF (7 mL) at rt under Ar was added Pd(PPh3)4 (0.20 g, 0.173 mmol) and hexamethylditin (5.0 g, 15.3 mmol), and the solution was heated to reflux for three days. The black mixture was cooled to rt and concentrated in vacuo. Separation of the residue (CC, 3:17 EtOAc–n-hexane) yielded 11 as a colorless oil (0.73 g, 70%): IR (neat) νmax 1736 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.23 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 9.3 Hz, H-4), 7.17 (1H, dd, J = 1.8, 2.4 Hz, H-6), 6.26 (1H, dd, J = 1.8, 9.3 Hz, H-3), 0.25 (9H, s, (CH3)3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.0 (C-2), 146.7 (C-4), 134.6 (C-6), 120.9 (C-3), 111.8 (C-5), −2.1 (3 × -CH3).

Bis(5α-bufa-16,20(21),22-trienolide-[2,3-b:2′ ,3′-e])pyrazine (12)

To a stirred solution of triflate 8 (0.90 g, 1.08 mmol) and pyrone 11 (0.64 g, 2.45 mmol) in THF (10 mL at rt under Ar) was added LiCl (0.68 g, 16.0 mmol) and Pd(PPh3)4 (0.220 g, 0.190 mmol), and the mixture was heated under reflux for three days. After the solution had cooled to rt, brine (10 mL) and DCM (10 mL) were added successively, and the aqueous phase was extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was separated (CC, 1:20 acetone–n-hexane) to afford 12 as an amorphous solid. Crystallization from cyclohexane–acetone provided bis-bufadienolide 12 as colorless needles (0.24 g, 31%): mp 242 °C (dec); IR (neat) νmax 1722 cm−1; 1H NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.25 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 9.3 Hz, H-22), 7.19 (1H, dd, J = 1.8, 2.4 Hz, H-21), 6.46 (1H, dd, J = 1.8, 9.3 Hz, H-23), 5.87 (1H, m, H-16), 2.92 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H–1α), 2.70 (1H, dd, H–4α), 2.49 (2H, m, H–1β, H–4β), 1.84 – 1.11 (16H), 0.95 (3H, s, CH3), 0.91 (1H, m), 0.85 (3H, s, CH3); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.1, 146.9, 145.3, 135.1, 129.7, 127.7, 123.8, 120.9, 113.1, 53.9, 53.1, 45.5, 44.1, 41.9, 35.7, 34.4, 32.5, 32.1, 29.6, 29.1, 28.6, 27.1, 19.1, 14.2, 11.5; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 725.4317 [M + H]+ (calcd for C48H57N2O4, 725.4318); anal. C 79.36, H 7.92, N 3.79%, calcd for C48H56N2O4, C 79.52, H 7.79, N 3.86%.

Aldehyde 15

To a solution of alcohol 141 (120 mg, 0.183 mmol) in isopropanol (10 mL) was added MnO2 (0.4 g, 4.58 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at rt. After 24 h the mixture was filtered through Celite, which was washed with DCM. Removal of solvent from the combined filtrate yielded the crude product as a solid. Purification (CC, 30% DCM–MeOH) and crystallization from DCM/EtOAc yielded 15 (80 mg, 0.122 mmol, 66%): mp 250 °C (dec); [α]D25 +29.8 (c 0.48, DCM); IR (film) νmax 3368, 3275, 2915, 1666, 1400, 1153 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.11 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-21), 5.80 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-20), 4.57 (2H, s, H-11), 3.13 (2H, d, J = 16.2 Hz, H-1β), 2.86 (2H, dd, J = 5.6, 18.2 Hz, H-4α), 2.74 – 2.58 (12H, m), 1.35 (6H, s), 1.13 (6H, s), 2.05 – 0.94 (22H, m); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 190.7 (C-21), 179.1 (C-17), 148.6 (C-2/3), 148.5 (C-2/3), 123.4 (C-20), 67.8 (C-11), 56.94, 56.87, 48.1, 46.6, 45.0, 42.2, 35.9, 34.8, 33.1, 32.0, 30.7, 27.8, 23.8, 21.5, 14.4; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 653.4236 [M + H]+ (calcd for C42H57N2O4, 653.4318); anal. C 70.99, H 9.06, N 3.89%, calcd for C42H56N2O4.4CH3OH, C 70.74, H 9.29, N 3.59%.

Bis-dihydro-4-pyrone 16

To a solution of aldehyde 15 (15 mg, 0.023 mmol) and Danishefsky’s diene (10 µL, 0.051 mmol)14 at −78 °C in DCM (10 mL) under Ar was added BF3·Et2O (12 µL, 0.012 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at −78 °C and then allowed to equilibrate to rt. After 48 h, no change was detectable by TLC, and an additional 12 µL of BF3·Et2O was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 14 days and then quenched with NaHCO3 (sat. aq.) and extracted with EtOAc. Purification (CC, 7:3 acetone–DCM) led to pyrazine 16 (3 mg, 17%): [α]D25 +106.2 (c 0.10, DCM); IR (neat) νmax 3363 (OH), 1672, 1401 (pyrazine ring) cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.38 (1H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-22), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-22), 5.42 (2H, dd, J = 1.0, 6.5 Hz, H-23), 5.20 (2H, m, J = 2.5, 8.5 Hz, H-20), 5.03 – 4.95 (2H, m, H-21), 4.55 (2H, s, H-11), 3.13 (2H, d, J = 16 Hz, H-1β), 2.82 (2H, br d, J = 17 Hz), 2.68 – 2.53 (4H, m, H-25), 2.44 – 2.36 (2H, m), 2.31 – 2.21 (2H, m), 2.06 – 1.83 (6H, m), 1.68 – 1.42 (8H, m), 1.14 – 1.05 (10H, m), 0.98 – 0.83 (4H, m); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 192.3 (C-24), 163.4 (C-22), 148.7 (C-2/3 or C-17), 148.4 (C-2/3 or C-17), 119.2 (C-20), 106.9 (C-23), 68.3, 67.9, 57.6, 54.6, 45.6, 45.1, 44.2, 42.5, 36.0, 34.9, 32.1, 31.0, 29.7, 27.9, 27.4, 24.2, 20.4, 14.4;HRMS (APCI+) m/z 789.4840 [M + H]+ (calcd for C50H65N2O6, 789.4843).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The very necessary financial assistance was provided by grants RO1CA90441-02-05 and 5RO1CA90441-07-08 from the Division of Cancer Treatment Diagnosis and Centers, National Cancer Institute, DHHS; the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission; the Robert B. Dalton Endowment Fund; Dr. Alec D. Keith, the J. W. Kieckhefer Foundation; the Margaret T. Morris Foundation, and the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation. For other helpful assistance we thank Drs. J.-C. Chapuis and V. J. R. V. Mukku, as well as F. Craciunescu and M. Dodson.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. 1H and 13C NMR spectra and a COSY spectrum of compounds 16.17 This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- 1.Antineoplastic Agents 563, for series part 562 see Pettit GR, Mendon a RF, Knight JC, Pettit RK. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:1922–1930. doi: 10.1021/np200411p.

- 2.(a) Pettit GR, Inoue M, Kamano Y, Herald DL, Arm C, Dufresne C, Christie ND, Schmidt JM, Doubek DL, Krupa TS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:2006–2007. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pettit GR, Inoue M, Kamano Y, Dufresne C, Christie N, Niven ML, Herald DL. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Com. 1988:865–867. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Dufresne C, Inoue M, Christie N, Schmidt JM, Doubek DL. Can. J. Chem. 1989;67:1509–1513. [Google Scholar]; (d) Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Inoue M, Dufresne C, Boyd MR, Herald CL, Schmidt JM, Doubek DL, Christie ND. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:429–431. [Google Scholar]; (e) Pettit GR, Xu J-P, Williams MD, Christie ND, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Boyd MR. J. Nat. Prod. 1994;57:52–63. doi: 10.1021/np50103a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Pettit GR, Ichihara Y, Xu J, Boyd MR, Williams MD. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:1507–1512. [Google Scholar]; (g) Pettit GR, Xu JP, Ichihara Y, Williams MD. Can. J. Chem. 1994;72:2260–2267. [Google Scholar]; (h) Pettit GR, Xu J-P, Schmidt JM, Boyd MR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995;5:2027–2032. [Google Scholar]; (i) Pettit GR, Tan R, Xu JP, Ichihara Y, Williams MD, Boyd MR. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:955–958. doi: 10.1021/np9800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Burgett AWG, Poulsen TB, Wangkanont K, Anderson DR, Kikuchi C, Shimada K, Okubo S, Fortner KC, Mimaki Y, Koruda M, Murphy JP, Schwalb DJ, Petrella EC, Cornella-Taracido I, Schirle M, Tallarico JA, Shair MD. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:639–647. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kumar AK, La Clair JJ, Fuchs PL. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5334–5337. doi: 10.1021/ol202139z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fortner KC, Kato D, Tanaka Y, Shair MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:275–280. doi: 10.1021/ja906996c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee S, LaCour TG, Fuchs PL. Chem. Reviews. 2009;109:2275–2314. doi: 10.1021/cr800365m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rudy A, López-Antón N, Dirsch VM, Vollmar AM. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:482–486. doi: 10.1021/np070534e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Moser BR. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:487–491. doi: 10.1021/np070536z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Flessner T, Jautelat R, Scholz U, Winterfeldt E. In: Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Herz W, Falk H, Kirby GW, editors. Vol. 87. Vienna: Springer; 2004. pp. 1–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) LaCour TG, Guo C, Bhandaru S, Boyd MR, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:692–707. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong JU, Sutton SC, Kim S, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10157–10158. [Google Scholar]; (c) Guo C, LaCour TG, Fuchs PL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00743-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Poza JJ, Rodríguez J, Jiménez C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nawasreh MM. Curr. Org. Chem. 2009;13:407–420. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee S, Jamieson D, Fuchs FL. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5–8. doi: 10.1021/ol802122p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gryszkiewicz-Wojtkielewicz A, Jastrzebska I, Morzycki JW, Romanowska DB. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:1257–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Taber DF, Joerger J-M. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:4155–4159. doi: 10.1021/jo800454w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nawasreh M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nawasreh M, Winterfeldt E. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:649–658. [Google Scholar]; (d) Bäsler S, Brunck A, Jautelat R, Winterfeldt E. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2000;83:1854–1880. [Google Scholar]; (e) Drögemüller M, Jautelat R, Winterfeldt E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:1572–1574. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kramer A, Ullmann U, Winterfeldt E. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I. 1993:2865–2867. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Rudy A, López-Antón N, Barth N, Pettit GR, Dirsch VM, Schulze-Osthoff K, Rehm M, Prehn JHM, Vogler M, Fulda S, Vollmar AM. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1930–1940. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dirsch VM, Müller IM, Eichhorst ST, Pettit GR, Kamano Y, Inoue M, Xu J-P, Ichihara Y, Wanner G, Vollmar AM. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8869–8876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Müller IM, Dirsch VM, Rudy A, López-Antón N, Pettit GR, Vollmar AM. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:1684–1689. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) López-Antón N, Rudy A, Barth N, Schmitz LM, Pettit GR, Schulze-Osthoff K, Dirsch VM, Vollmar AM. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33078–33086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Kuo P-C, Kuo T-H, Su C-R, Liou M-J, Wu T-S. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:3392–3396. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kamano Y, Yamashita A, Nogawa T, Morita H, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Segawa T, Yukita A, Saito K, Katsuyama M, Pettit GR. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:5440–5447. doi: 10.1021/jm0202066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kamano Y, Nogawa T, Yamashita A, Hayashi M, Inoue M, Drašar P, Pettit GR. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:1001–1005. doi: 10.1021/np0200360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kamano Y, Yamashita A, Takeuchi H, Kohyama K, Nogawa T, Pettit GR. Res. Inst. Integ. Sci. Kanagawa University (Japan) 2000:29–38. [Google Scholar]; (e) Vu H, Ianosi-Irimie M, Danchuk S, Rabon E, Nogawa T, Kamano Y, Pettit GR, Wiese T, Puschett JB. Exper. Biol. Med. 2006;231:215–220. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) LaMarca HL, Morris CA, Pettit GR, Nogawa T, Puschett JB. Placenta. 2006;27:984–988. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Wang J-D, Narui T, Takatsuki S, Hashimoto T, Kobayashi F, Ekimoto H, Abuki H, Ninjima K, Okuyama T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991;39:2135–2137. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yamagishi T, Yan X-Z, Wu R-Y, McPhail DR, McPhail AT, Lee K-H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988;36:1615– 1617. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Kupchan SM, Ognyanov I, Moniot JL. Bioorg. Chem. 1971;1:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ohta G, Koshi K, Obata K. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1968;16:1487–1497. [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith HE, Hicks AA. J. Org. Chem. 1971;36:3659–3668. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith SC, Heathcock CH. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:6379–6380. [Google Scholar]; (d) Heathcock CH, Smith SC. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6828–6839. [Google Scholar]; (e) Pan Y, Merriman RL, Tanzer LR, Fuchs PL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1992;2:967–972. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lietard J, Meyer A, Vasseur J-J, Morvan F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:8795–9798. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, Meinwald J. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:6693–6699. doi: 10.1021/jo951394t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho C-G, Park J-S, Jung I-H, Lee H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:1065–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott WJ, Crisp GT, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4630–4632. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Misico RI, Gil RR, Oberti JC, Veleiro AS, Burton G. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:1329–1332. doi: 10.1021/np000022z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gupta S, Krasnoff SB, Renwick JAA, Roberts DW, Steiner JR, Clardy J. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:1062–1067. [Google Scholar]; (c) Suenaga K, Kigoshi H, Yamada K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:5151–5154. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sharma P, Powell KJ, Burnley J, Awaad AS, Moses JE. Synthesis. 2011:2865–2892. [Google Scholar]; (e) Wilk W, Waldmann H, Kaiser M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:2304–2309. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Josephsohn NS, Snapper ML, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4018–4019. doi: 10.1021/ja030033p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Danishefsky SJ, DeNinno MP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1987;99:15–23. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kerwin JF, Jr, Danishefsky S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:3739–3742. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardi R, Castelli PP, Gandolfi R, Ercoli A. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1961;91:1250–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutney JP, Piotrowska K, Somerville J, Huang S-P, Rettig SJ. Can. J. Chem. 1989;67:580–589. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The spectra of the other compounds characterized in this report are no longer available.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.