Abstract

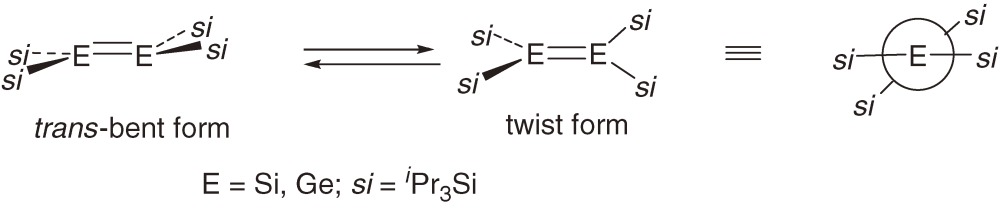

Structure and properties of silicon-silicon doubly bonded compounds (disilenes) are shown to be remarkably different from those of alkenes. X-Ray structural analysis of a series of acyclic tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)disilenes has shown that the geometry of these disilenes is quite flexible, and planar, twist or trans-bent depending on the bulkiness and shape of the trialkylsilyl substituents. Thermal and photochemical interconversion between a cyclotetrasilene and the corresponding bicyclo[1.1.0]tetrasilane occurs via either 1,2-silyl migration or a concerted electrocyclic reaction depending on the ring substituents without intermediacy of the corresponding tetrasila-1,3-diene. Theoretical and spectroscopic studies of a stable spiropentasiladiene have revealed a unique feature of the spiroconjugation in this system. Starting with a stable dialkylsilylene, a number of elaborated disilenes including trisilaallene and its germanium congeners are synthesized. Unlike carbon allenes, the trisilaallene has remarkably bent and fluxional geometry, suggesting the importance of the π-σ* orbital mixing. 14-Electron three-coordinate disilene-palladium complexes are found to have much stronger π-complex character than related 16-electron tetracoordinate complexes.

Keywords: silicon, germanium, double bond, synthesis, structure, theoretical calculations

Introduction

So-called “double-bond rule” states that unlike carbon, the elements with a valence principal quantum number of three or greater do not effectively participate in π bonding.1) In accord with this rule, multiply bonded compounds of silicon had been believed to be non-existent or highly unstable until the first synthesis of stable disilene (Mes2Si=SiMes2; Mes = 2,4,5-trimethylphenyl)2) and silaethene [Ad(Me3SiO)C=Si(SiMe3)2, Ad = 1-adamantyl]3) were achieved by West et al. and Brook et al., respectively, in 1981. Since then, much attention has been focused on various aspects of the chemistry of silicon unsaturated compounds including their bonding and structure, spectroscopic properties, reactivity, and application to the synthesis of novel types of organosilicon compounds; a number of reviews have been published for their experimental4) and theoretical aspects.5) Now studies in this research field look heading for two directions, in addition to further synthetic development of new types of unsaturated silicon compounds; (1) application of their unique electronic properties towards the material science and (2) restructuring of a general theory of bonding and structure of heavy main group elements including silicon. The former is just its beginning but the latter looks biding its time. Actually, thanks to interplay between theory and experiment, remarkable distinctions of bonding and structure between silicon unsaturated compounds and their carbon congeners have been accumulated.

We have created a number of thermally stable silicon unsaturated compounds with Si=Si, Si=C, and Si=X (X = S, Se, Te, etc.) bonds and elucidated their unique properties since 1994.6) In this account, the results are discussed with a focus on the differences in bonding and structure between carbon and silicon unsaturated compounds and their origin.

|

[1] |

|

[2] |

|

[3] |

|

[4] |

|

[5] |

1. Stable acyclic tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)disilenes

1.1. Synthesis.

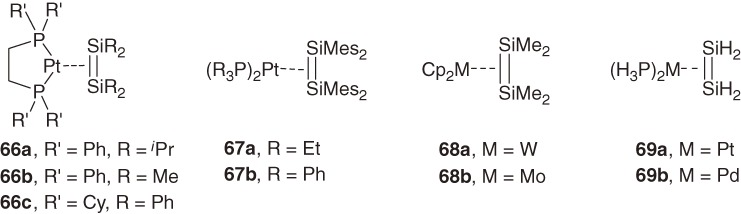

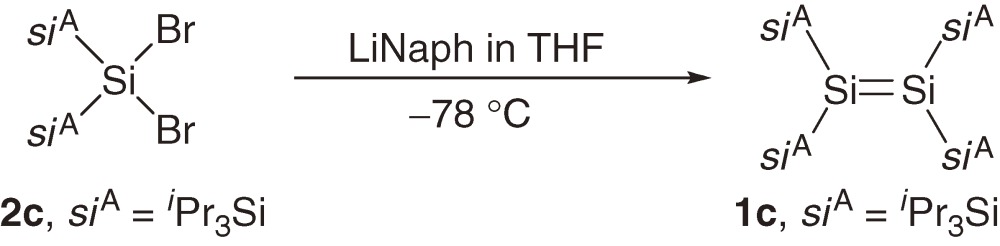

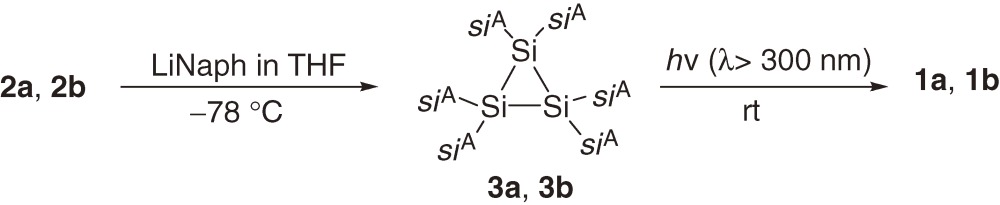

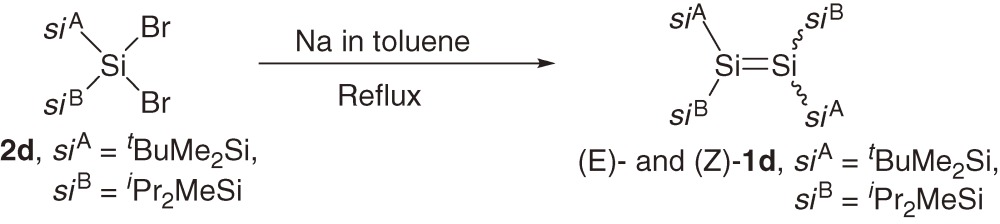

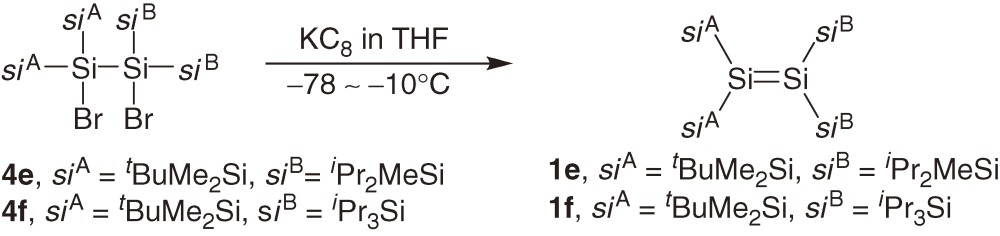

A series of acyclic tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)disilenes 1a–1c are synthesized typically using reductive coupling of the corresponding bis(trialkylsilyl)dibromosilanes 2a–2c (eqs [1]–[3]).7,8a)) The products of the reduction of 2a–2c are dependent on the reaction conditions and steric bulkiness of the substituents. For example, the reduction of 2a and 2b with sodium in toluene affords disilenes 1a and 1b but the reduction of 2a and 2b with lithium naphthalenide (LiNaph) in THF at −78 ℃ gives the corresponding cyclotrisilanes 3a and 3b, which are further converted to 1a and 1b by the photolysis using a high-pressure Hg lamp (eq [3]).8a)) Disilene 1c with bulkier silyl substituents is obtained directly by the reduction of 2c using LiNaph/THF at the low temperature (eq [2]), while 1c is not formed by reducing 2c with Na in toluene.8a)) (E)- and (Z)-tetrakis(triakylsilyl)disilenes, (E)-1d and (Z)-1d, are synthesized using a similar reductive coupling of dibromosilane 2d with two different silyl substituents (eq [4]). The reduction affords a ca. 2:1 mixture of (E)- and (Z)-1d in solution but pure (E)-1d is obtained as single crystals by recrystallization of the mixture from hexane.8b)) A2Si=SiB2 type disilenes 1e and 1f are synthesized by the reduction of the corresponding tetrasilyl-1,2-dibromodisilanes 4e and 4f, respectively (eq [5]).8c))

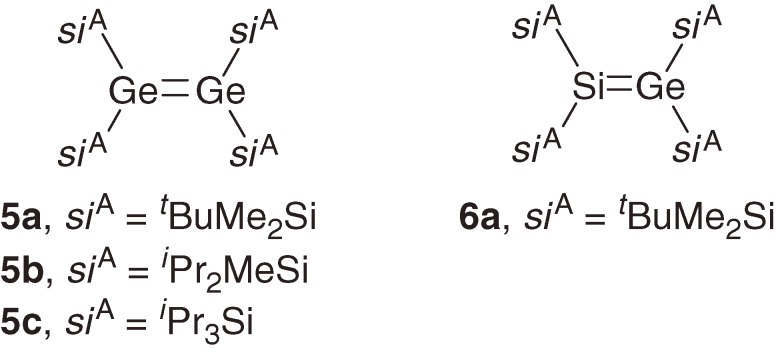

Digermenes 5a–5c8d),8e)) and germasilene 6a8e)) are synthesized using similar reduction methods (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

All these dimetallenes are thermally stable and can be handled in a glove box at ambient temperatures but are highly air- and moisture-sensitive in solution and in the solid state.

|

[6] |

1.2. Spectroscopic properties.

Tetrasilyldisilenes 1a–1c are yellow to light orange in the solid state, and expectedly, the UV-vis spectra of disilenes 1a–1c measured in KBr pellets are similar to each other with the band maxima at around 420 nm.8a)) In Table 1 are summarized the UV-vis absorption spectra of acyclic tetrasilyldimetallenes 1a–1f and related dimetallenes at room temperature in a hydrocarbon solvent. Interesting spectral features of tetrasilyldimetallenes are found in the table: (1) Whereas these tetrasilyldisilenes have no aromatic substituents, the longest absorption maxima are found at a wavelength longer than 400 nm. Sterically less hindered dimetallenes 1b, 1e, 5a, 5b, and 6a show the longest wavelength band maxima at around 420 nm with relatively large absorptivity (ε > 5000); the λmax is even similar to that for Mes2Si=SiMes2 (7).9) The band assignable to the π→π* transition of normal or less distorted dimetallenes appears at much longer wavelengths than those of alkenes, which are usually transparent in the wavelength region longer than 300 nm. It is suggested that the energy splitting between π and π* MOs in these dimetallenes is similar irrespective of the central elements that are silicon or germanium, while the splitting is much smaller than that in alkenes. (2) Absorption spectral behavior of disilene 1c and digermene 5c with relatively bulky silyl substituents is rather unusual. In solution, 1c and 5c show the longest wavelength band at much longer wavelength of 480 and 472 nm with relatively smaller absorptivity than those for dimetallenes categorized as (1). The spectra of 1c and 5c with bulky tri(isopropyl)silyl substituents are remarkably temperature dependent with increasing absorptivity of the 420 nm bands at lower temperatures. The behavior may be explained by the temperature-dependent equilibrium between trans-bent and twist forms in solution as shown in eq [6], where the twist form is supposed to have a smaller π-π* splitting energy than that for the trans-bent form. The explanation is consistent with the UV-vis spectral characteristics of a disilene with bulkier di(t-butyl)methylsilyl substituents 8 [(tBu2MeSi)2Si=Si(SiMetBu2)2] reported by Sekiguchi et al.10) that has remarkably twisted geometry around the Si=Si bond (twist angle, 55°); the longest wavelength band of 8 shows the maximum at 620 nm with the absorptivity of 1300. (3) Disilene 1a and digermene 5a with intermediate bulkiness of silyl substituents show the longest wavelength band at around 420 nm but with smaller absorptivity and broad bandwidth than those of dimetallenes categorized as (1). The bands sharpened remarkably at lower temperatures. The less remarkable temperature dependence of the spectra of 1a and 5a than that of 1c and 5c may not be compatible with the equilibrium shown in eq [6] but suggest significant fluctuation around their trans-bent geometry.

Table 1.

UV-vis absorption maxima and absorptivity (in parentheses)a) and 29Si NMR chemical shifts for unsaturated silicon nuclei of tetrasilyldimetallenes

| Compound | λmax/nm (ε/103) | δ(29Si)/ppm | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 290 (2.5), 360 (1.9), 420 (2.8) | 142.1 | 8a) |

| 1b | 293 (2.1), 357 (1.4), 412 (7.6) | 144.5 | 8a) |

| 1c | 296 (5.4), 370 (2.4), 425 (1.9), 480 (2.2) | 154.5 | 8a) |

| 1d | —b) | 141.9 | 8b) |

| 1e | 293 (2.6), 359 (2.0), 413 (5.0) | 132.4, 156.6 | 8c) |

| 1f | —b) | 142.0, 152.7 | 8c) |

| 8 | 290 (8.2), 375 (2.0), 612 (1.3) | 155.5 | 10 |

| 5a | 266 (5.3), 295 (2.6), 362 (3.1), 421 (7.0) | — | 8d), 8e) |

| 5b | 361 (2.9), 413 (16.1) | — | 8d) |

| 5c | 277 (3.5), 367 (2.2), 432 (2.1), 472 (2.0) | — | 8d) |

| 6a | 359 (2.0), 413 (5.0) | 144.0 | 8e) |

a) In hexane or 3-methylpentane. b) Not measured.

29Si NMR chemical shifts for the unsaturated silicon nuclei of acyclic tetrasilyldisilenes are shown in Table 1. The chemical shifts are in the range of 136–157 ppm, which are much lower field shifted than those for typical alkyl- and aryl-substituted disilenes; δ 63.7 for 79) and δ 90.3 for (E)-tBu(Mes)Si=Si(Mes)tBu (9).9) The origin of remarkable lower field shift of 29Si resonances for tetrasilyldisilenes has been studied by the analysis of their chemical shift tensors in the solid state.11) Extremely large deshielding along one principal axis for disilenes 1b and 1c is related to their low σ→π* transition energies; the values δ11, δ22, and δ33 are found to be 414, 114, and −100 for 1b; 412, 149, and −69 for 1c, while 181, 31, and −22 for 7.11)

1.3. Molecular structures determined by X-ray crystallography.

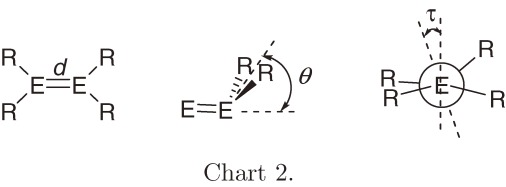

Structural parameters of dimetallenes 1a–1f, 5a–5c, and 6a determined by X-ray crystallography are listed in Table 2, together with those of related dimetallenes reported by other groups; E=E bond distances (d) in Å, bent angles (θ) in deg defined as the angle between E-E bond and R-E-R plane, and twist angle (τ) in deg, the angle between two R-E-R planes for R2E=ER2. The geometry around E=E double bond of all the dimetallenes is diversified depending on the trialkylsilyl substituents. Disilenes 1b and 1c and digermenes 5b and 5d are bent without twisting with the bend angles in the order 1b < 5b < 1c < 5c. Disilenes 1a, 1e, 1f, and 7, digermene 5a, and germasilene 6a are twisted without bending with the twist angles in the order 5a∼6a < 1a < 1e ≪ 1f ≪ 7. Disilene (E)-1d has highest planarity among dimetallenes shown in the table probably because the two different substituents in (E)-1d can be arranged so as to minimize the steric strain between the substituents at the planar geometry. Dimetallenes having isopropyl-substituted silyl groups favor trans-bent geometry in the solid state, while dimetallenes with t-butyl-substituted silyl groups tend to twist. Because electronic effects of all trialkylsilyl groups studied here are similar to each other, the distortion modes seem to be determined mainly by the effects of the size and shape of the substituents. Theoretical studies have revealed that the geometry around an E=E bond of simple dimetallenes like H2E=EH2 and Me2E=EMe2 is trans-bent,5) while (H3Si)2E=E(SiH3)212) features planar geometry. The geometrical preference of tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)dimetallenes found experimentally suggest that the geometry is very flexible and the major factor determining the preference is the steric effects. In the next section, electronic models for the distortion around E=E bond and important factors controlling the geometrical preference are discussed more in detail.

Table 2.

Structural parameters for tetrasilyldimetallenes and related dimetallenes

| Compound | Si=Si distance d/Å | Bent anglea θ/deg | Twist angleb τ/deg | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disilenes | ||||

| 1a | 2.202(1) | 0.1 | 8.9 | 8a) |

| 1b | 2.228(2) | 5.4 | 0.0 | 8a) |

| 1c | 2.251(1) | 10.2 | 0.0 | 8a) |

| 1d | 2.196(3) | 0.65 | 0.0 | 8b) |

| 1ec | 2.198(1), 2.1942(8) | 0.0, 0.0 | 8.97, 11.73 | 8c) |

| 1f | 2.2011(9) | 0.0 | 27.95 | 8c) |

| Mes2Si=SiMes2 (7) | 2.143 | 12, 14 | 3 | 13 |

| 7/C7H8 | 2.160 | 18 | 12 | 9 |

| 7/THF | 2.146 | 0 | 13 | 13 |

| (tBu2MeSi)2Si=Si(SiMeBut2)2 (8) | 2.2598(18) | ∼0 | 54.5 | 10 |

| Digermenes | ||||

| 5a | 2.2703 | 0.3 | 7.47 | 8e) |

| 5bc | 2.268(1), 2.266(1) | 5.9, 7.1 | 0.0, 0.0 | 8d) |

| 5c | 2.298(1) | 16.4 | 0.0 | 8d) |

| Mes2Ge=GeMes2 (9) | 2.2856(8) | 33.4 | 2.9 | 14 |

| Tip2Ge=GeTip2 (10) | 2.213(1) | 12.3 | 13.7 | 15 |

| Germasilenes | ||||

| 6a | 2.2208(8) | 0.6 | 7.51 | 8e) |

| Mes2Ge=Si(SiBut3)2 (11) | 2.2769(8) | 0 | 24.67 | 16 |

a) Bent angle (θ) in deg is defined as the angle between E-E bond and R-E-R plane. b) Twist angle (τ) in deg is defined as the angle between two R-E-R planes. c) Two crystallographically independent molecules show slightly different structural parameters.

1.4. Theoretical models for distortion modes around double bond.

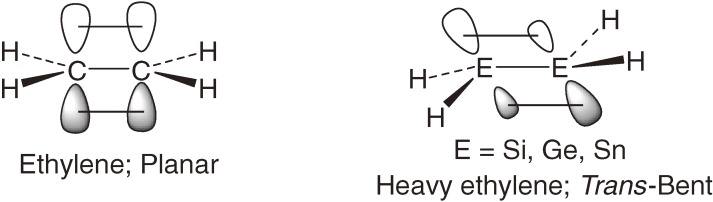

Theoretical studies have shown that optimized geometry of heavy group-14 ethylenes (dimetallenes; H2M=MH2, M = Si, Ge, and Sn) is trans-bent in contrast to planar ethylene (E = C) (Chart 3).5)

Chart 3.

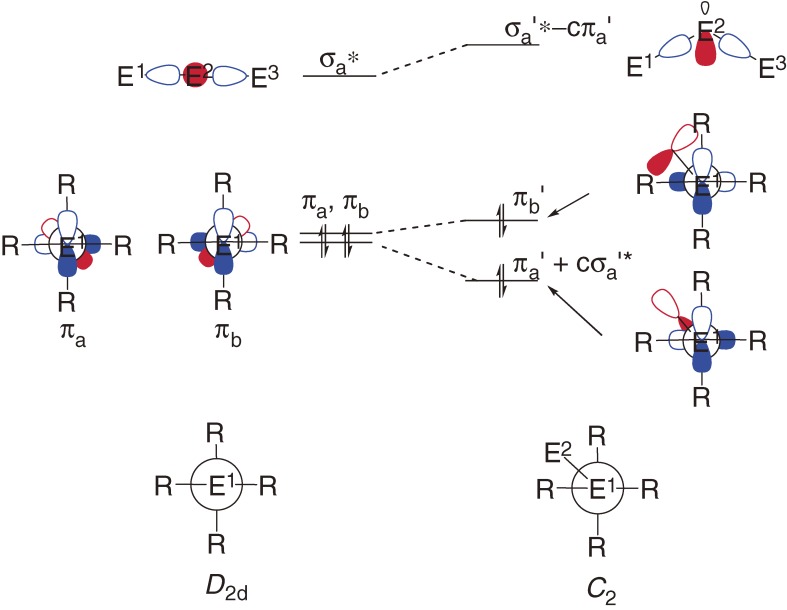

Bonding nature of the E=E double bonds is outlined using the CGMT (Carter-Goddard-Malrieu-Trinquier) model17) as follows: When two EH2 groups having an in-plane n orbital and an out-of-plane pπ orbital approach to each other to form a planar E=E double bond, an overlap between the two n orbitals form σ and σ* orbitals and an overlap between the two pπ orbitals forms π and π* orbitals, where the orbital energy levels of pπ, n, σ, σ*, π and π* are given by εpπ, εn, εσ, εσ*, επ and επ*, respectively (Fig. 1a). The n orbital is usually lower in energy than pπ orbital with Δεpn, which is often replaced by ΔEST (singlet-triplet energy difference, ET − ES) in the CGMT model.17c)) The σ-σ* and π-π* splitting energies are reasonably assumed to be the σ and π bond energies Eσ and Eπ, respectively; Eσ = εσ* − εσ, and Eπ = επ* − επ. The condition of forming a double bond is επ < εσ* and εσ < επ*, i.e. (−1/2)Eσ+π < ΔEST < (1/2)Eσ+π, where Eσ+π = Eσ + Eπ. We can expect using PMO (perturbation molecular orbital) theory18) that when εσ* and επ are close to each other, effective π-σ* orbital mixing will lead to significant trans-bending (Fig. 1b). The CGMT model predicts that a dimetallene would favor the trans-bent geometry if (1/4)Eσ+π < ΔEST < (1/2)Eσ+π. Bond dissociation energy (BDE) of the heavy ethylene to two heavy methylenes (H2E:) is estimated to be BDE = Eσ+π − 2ΔEST. The BDE will decrease with increasing ΔEST, if Eσ+π is constant.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic MO representation of the formation of dimetallenes by dimerization of the corresponding metallylene. (b) Stabilization of the bonding π MO level by its secondary interaction with a higher-lying σ* MO orbital.

Although the CGMT model has reasonable grounds and is useful to understand the distinct differences in bonding between planar ethylene and trans-bent heavy ethylenes, the model should be utilized with several cautions.19) (1) Because both ΔEST and Eσ+π are variables depending on element E, the proximity of the π and σ* levels is determined by the two factors, ΔEST and Eσ+π. Although large ΔEST values of R2E: are often taken to be an indication of the trans-bent geometry of the H2E=EH2, the rule cannot be extended to the discussion between different elements; Eσ and Eπ for heavier group-14 elements are much smaller than those for carbon. In accord with the CGMT model, tetrasilyldimetallenes [(H3Si)2E=E(SiH3)2, E = Si, Ge, and Sn] whose component silylene (H3Si)2E: has smaller ΔEST than the corresponding H2E: are shown theoretically to be planar around the E=E bond.12) However, although the ΔEST of F2C: (57.6 kcal mol−1)20) is even much larger than that of GeH2 (23.1 kcal mol−1),21) F2C=CF2 is a planar molecule, while H2Ge=GeH2 is trans-bent. (2) In the CGMT model, the σ* orbital participating in the π-σ* orbital mixing is only σ*(E–E) orbital, whereas other valence σ* orbitals in H2E=EH2, i.e. four σ*(E–H) orbitals, may contribute to the π-σ* orbital mixing for the distortion modes of the geometry. A theoretical study has shown that mono-anion of disilene [H2Si=SiH2]•− adopts trans- and cis-bent geometries due to significant mixing between the π*(SOMO) and a σ*(Si-H) orbital with proper symmetry representation.19c),22) (3) Applicability of the CGMT model to heavy ethylenes with bulky substituents is less satisfactory because the steric effects are the controlling factor determining the geometry as discussed in the previous section.

Recently, the author has discussed the distortion modes, trans- and cis-bending and twisting of H2E=EH2 (E = C, Si, and Ge) and their anions in detail in terms of a more generalized π-σ* orbital mixing model using the PMO theory.19c)) The model predicts that trans- and cis-bent geometries of neutral dimetallenes may be more stable than the planar geometry but with very small energy gains, while these geometries should be largely stabilized with significant bent angles and stabilization energies in dimetallene anions. Twisting around the double bonds of dimetallenes may lower the energy of the anions. The above prediction is verified by the potential energy surface calculations at the B3LYP/6-311++G(3df,3pd) level.19c)) It should be noted that the π-σ* orbital mixing underlie the bonding and structure issues of unsaturated compounds of heavy main-group elements, even though the substituent steric effects are often the controlling factor of the geometry as shown in Section 1.3.

1.5. E,Z- and formal dyotropic isomerization of disilenes.

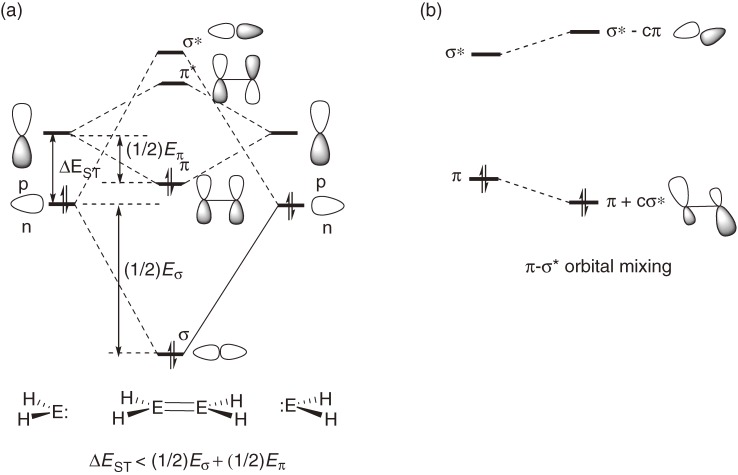

Thermal E,Z-isomerization of alkenes is known to occur through the rotation around the C=C bond but usually with very high activation energy of 40–60 kcal mol−1. On the other hand, at least three distinct pathways should be taken into account for the E,Z-isomerization of heavier alkenes as shown in Scheme 1 ; rotation around Si-Si bond (path 1), dissociation-recombination (path 2), and disilene-silylsilylene interconversion (path 3). While paths 1 and 2 give rise to only E,Z-isomerization, path 3 may produce an A2Si=SiB2-type isomer in addition.

Scheme 1.

Three possible pathways of E,Z-isomerization of disilenes.

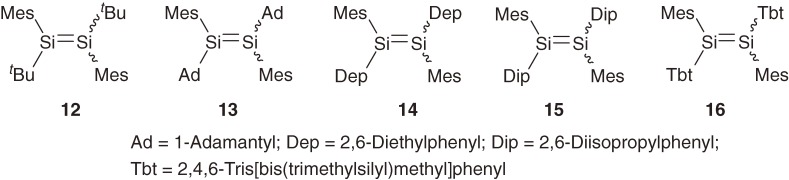

|

[7] |

|

[8] |

Among disilenes shown in Chart 4, 12–15 are shown to undergo Z→E isomerization via path 1 with the activation free energy (ΔG≠ at 350 K) of ca. 26.2–27.4 kcal mol−1.4a)) On the other hand, the Z→E isomerization of disilene 16 was confirmed to occur via path 2 with the ΔG≠ value of 22.7 kcal mol−1 at 350 K.4a),23) The dissociation of 16 into a pair of the corresponding silylene is evidenced by trapping of the silylene with alkenes and acetylenes. Easy Si=Si double bond cleavage of 16 into the corresponding silylenes suggests that the BDE of the Si=Si bond in 16 is reduced by large steric hindrance among bulky substituents, in addition to the intrinsically small BDE of disilene as expected by the CGMT model (Section 1.4).

Chart 4.

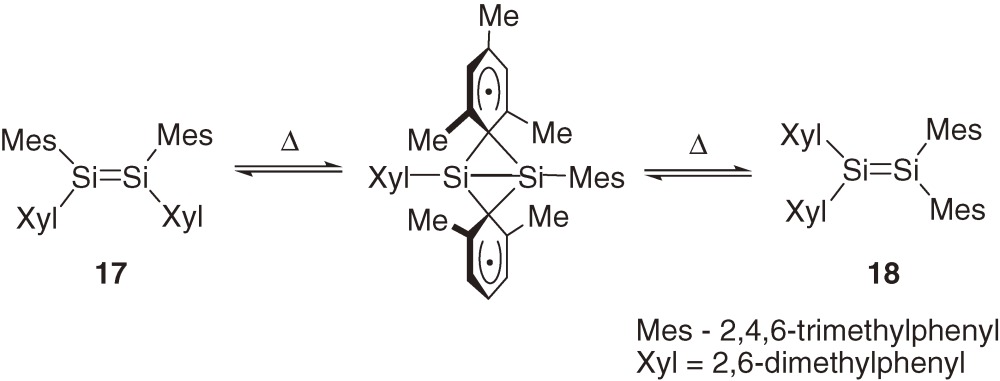

Related isomerization of (Z)-ABSi=SiAB-type tetraaryldisilenes into A2Si=SiB2-type disilenes and its reverse reaction has been proposed by West et al. to occur via a concerted dyotropic mechanism24) rather than path 3.25) Typically, disilene 17 is shown to isomerize to 18 at around 70 ℃ probably via a bicyclobutane-like transition state or intermediate (eq [7]). The activation free energy for the dyotropic rearrangement is estimated to be even smaller than that for the E,Z-isomerization via path 1 but the activation entropy is much larger in accord with the highly restricted transition state; for 18→17, ΔH≠ = 15 ± 2 kcal mol−1 and ΔS≠ = −36 ± 4 cal mol−1 K−1.25b))

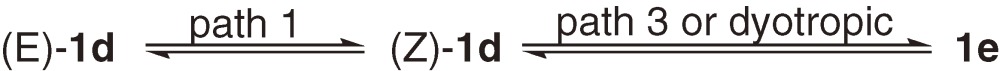

The 29Si NMR spectrum of a ca. 2:1 mixture of (E)-1d and (Z)-1d is remarkably dependent on temperature (eq [8]). Two pairs of signals due to tBuMe2Si and iPr2MeSi groups are observed independently at 273 K, but coalesce at around 303 K to give two sharp singlets at higher temperature than 330 K, indicating that facile isomerization between (E)- and (Z)-1d occurs even at room temperature with the ΔG≠ value of ca. 15.3 kcal mol−1 (Z→E) at 303 K.8b)) Two 29Si signals due to a small amount of contaminated A2Si=SiB2 type isomer 1e is observed to remain sharp in the temperature range of 273–310 K, indicating that a dyotropic or path 3 rearrangement does not participate in the E,Z-isomerization. Because no dissociation of the tetrasilyldisilenes into the corresponding silylenes is observed, the E,Z-isomerization is concluded to occur via the rotation around the Si-Si bond (path 1). The activation free energy for the E,Z-isomerization of 1d is 10 kcal mol−1 smaller than those of disilenes 12–15, probably because of effective σ-π conjugation at the twisted transition state of the former.

When pure 1e is kept at 283 K for 7 days, an equilibrium was established with the ratio of (E)-1d, (Z)-1d, and 1e = 1:0.47:0.67 (eq [8]).8b),8c)) The activation free energy for the rearrangement from 1e to (Z)- or (E)-1d at 283 K is 17.4 kcal mol−1, which is ca. 2 kcal mol−1 larger than that for the E,Z-isomerization and 7.7 kcal mol−1 smaller than those for the dyotropic rearrangement of tetraaryldisilenes reported by West et al.25) A disilene-silylsilylene rearrangement may not be excluded for the formal dyotropic rearrangement between 1e and 1d, because of the high 1,2-migratory aptitude of silyl groups.

|

[9] |

2. Stable cyclic persilyldisilenes

2.1. Cyclotrisilene and cyclotetrasilene.

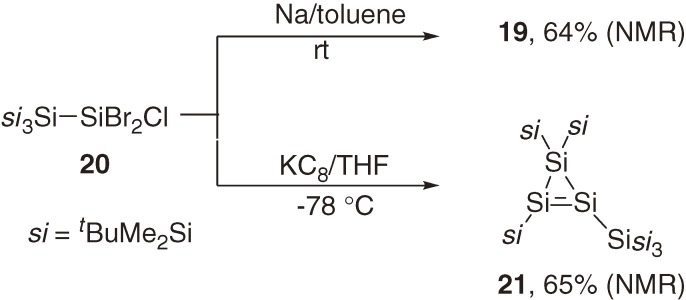

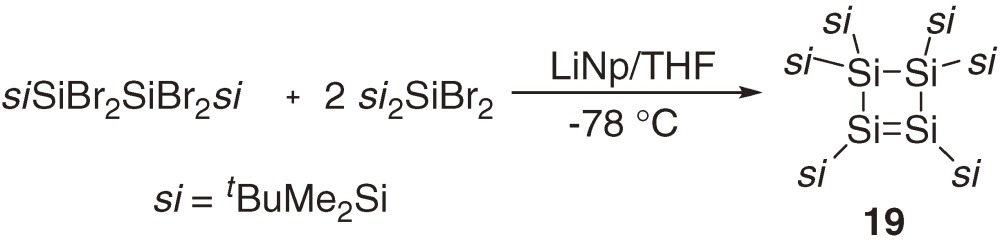

As the first stable cyclic disilene, cyclotetrasilene 19 was synthesized in 13.5% yield by co-coupling of bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl)dichlorosilane and (t-butyldimethylsilyl)trichlorosilane using lithium naphthalenide in THF at −78 ℃ (eq [9]).26) An improved synthetic method using the reduction of (trisilylsilyl)dibromochlorosilane 20 with Na in toluene at room temperature gave 19 in 64% yield.27) Interestingly, the first cyclotrisilene 21 was obtained as a major product when the reduction of 20 was performed with KC8 in THF at −78 ℃ (Scheme 2).27,28) The Si=Si bond lengths of cyclotetrasilene 19 (2.174(4) Å)26) and cyclotrisilene 21 (2.132(2) Å)29) are a little shorter than those of acyclic tetrasilyldisilenes 1a–1f (Table 2), while the ring Si–Si single bond length of 19 (2.544(4) Å) is even longer than the normal Si-Si length (2.35 Å).26) The longest absorption maxima for 19 and 21 appear at 465 nm (ε 6810)26) and 482 nm (ε 2640),27) respectively. These maxima are more than 40 nm red-shifted from those of the acyclic tetrasilyldisilenes (Table 1). Two 29Si NMR resonances of the unsaturated silicon nuclei of cyclotrisilene 21 appeared at δ +81.9 and δ +99.8, which are significantly high-field shifted relative to those for acyclic tetrasilyldisilenes (δ 142–157, Table 1) and cyclotetrasilene 19 (δ 160.4). The tendency of the 29Si chemical shifts among the acyclic tetrasilyldisilenes, 19, and 21 is parallel to that of the corresponding 13C NMR chemical shifts among ethylene (δ 123.5), cyclopropene (δ 108.7), and cyclobutene (δ 137.2), suggesting a similar origin for the tendency.

Scheme 2.

2.2. Interconversion among Si4R6 isomers.

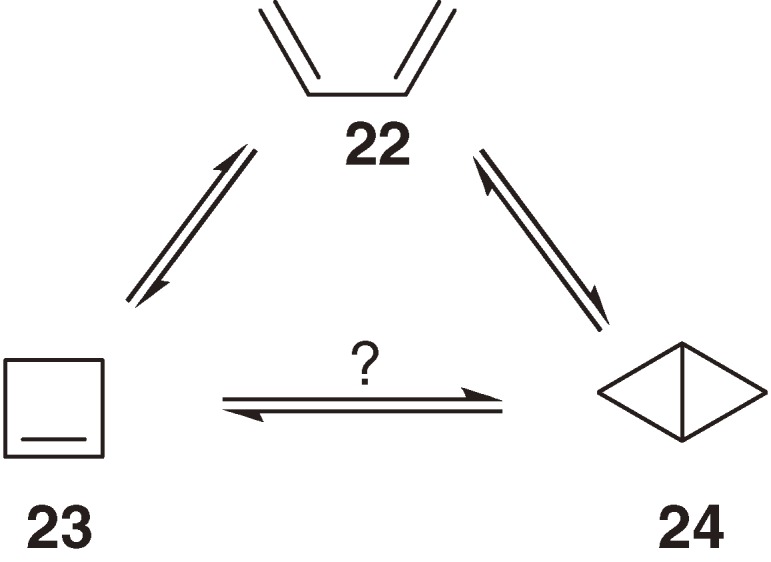

Thermal and photochemical interconversion among C4H6 isomers 22–24 is one of the most fundamental electrocyclic reactions, and hence, has been investigated in detail including its stereochemistry (Scheme 3).30) However, it is hard to investigate the interconversion between cyclobutene 23 and bicyclobutane 24, partly because 1,3-butadiene is the most stable isomer among 22–24. Although the thermal interconversion between 23 and 24 is predicted to occur concertedly,30a)) no direct isomerization among them has been observed.

Scheme 3.

Interconversion among C4H6 valence isomers.

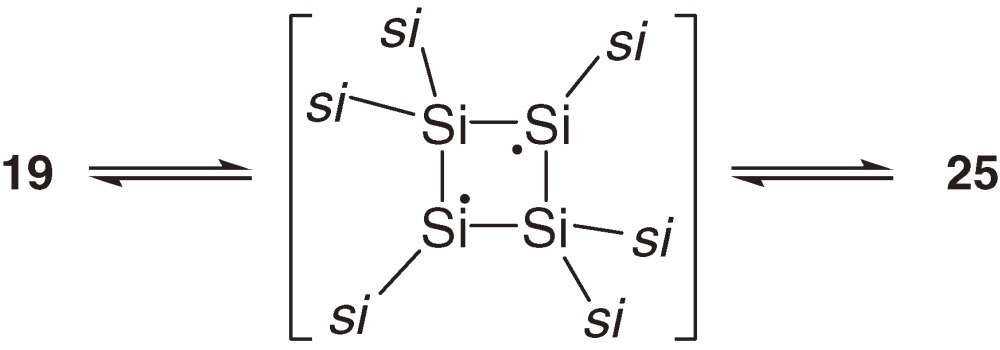

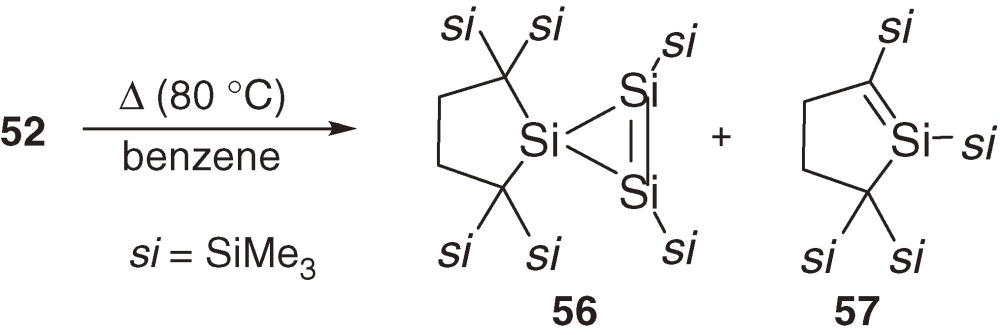

Thermal and photochemical isomerization among Si4R6 (R = tBuMe2Si) isomers is observed only between cyclotetrasilene 19 and the corresponding bicyclotetrasilane 25 without intervention of the corresponding 1,3-tetrasiladiene 26 (Scheme 4).26) Cyclotetrasilene 19 isomerizes to bicyclotetrasilane 25 under irradiation (>420 nm) and 25 reverts to 19 thermally. In this particular system, cyclotetrasilene 19 is more stable than bicyclotetrasilane 25, while theoretical calculations have shown that, among parent Si4H6 isomers, bicyclotetrasilane is more stable than cyclotetrasilene and s-trans-1,3-tetrasiladiene with the energy differences of 3.0 and 33.3 kcal mol−1 at the B3LYP/6-311+G** level.31) Because the energy difference between bicyclotetrasilane and cyclotetrasilene is not very large, the relative stability may be dependent on the substituents.

Scheme 4.

Interconversion among Si4si6 valence isomers.

Labeling experiments using 19 and 25 that are partially substituted by tBu(CD3)2Si groups have revealed however that the interconversion between 19 and 25 occurs through a 1,3-diradical intermediate formed by the 1,2-silyl migration of 19 as shown in eq [10].32)

|

[10] |

|

[11] |

|

[12] |

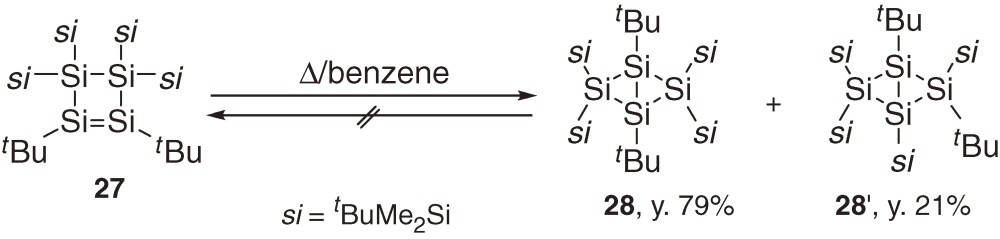

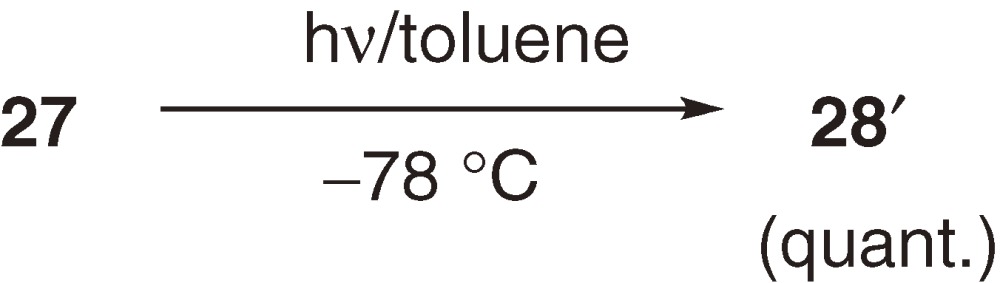

Cyclotetrasilene 27 having t-butyl groups at unsaturated silicon atoms is thermally less stable than the corresponding bicyclotetrasilanes 28 and 28′ (eq [11]). Thus, heating 27 in benzene affords irreversibly a mixture of 28 and 28′, which are produced via concerted skeletal isomerization and 1,2-silyl migration, respectively (eq [11]).33) During the isomerization, no evidence is obtained for the intermediary formation of the corresponding 1,3-tetrasiladiene. Irradiation (λ > 420 nm) of 27 at low temperature gives 28′ quantitatively (eq [12]).33) Thermal isomerization of 27 to 28 is regarded to be complementary to the concerted isomerization observed among C4H6 isomers, because direct electrocyclic isomerization between bicyclobutane and cyclobutene is hard to be observed in the carbon systems.

2.3. Spiropentasiladiene.

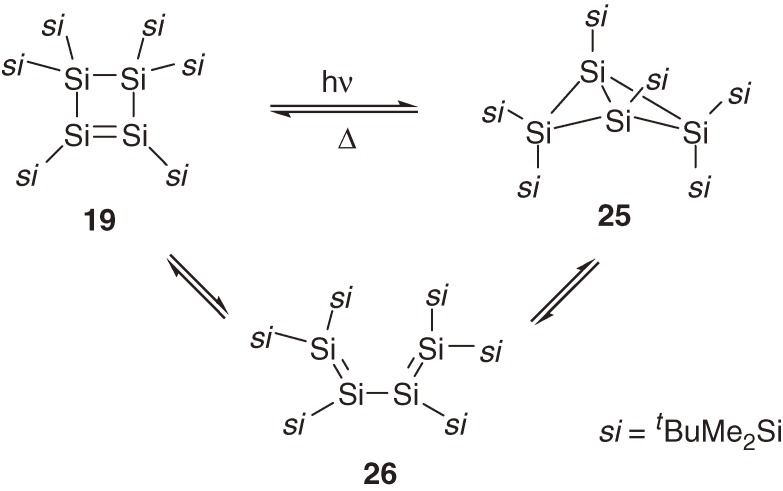

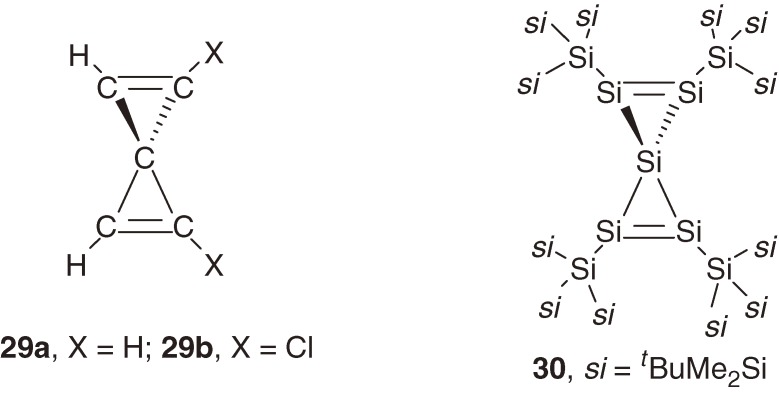

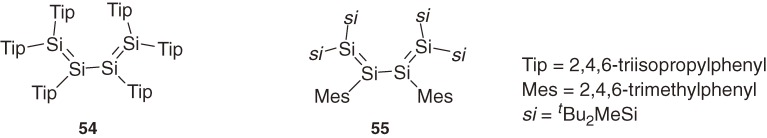

Spiropentadiene constitutes one of the smallest spiroconjugation systems and has attracted much attention theoretically;34) the two perpendicularly arranged anti-bonding π* orbitals of spiropentadiene with D2d symmetry interact to each other to split into two π* orbitals [(π1* + π2*) and (π1* − π2*)] with different energy levels, while the two bonding π orbitals do not interact and remain degenerate (Fig. 2, left). The synthetic study of parent spiropentadiene 29a and its 1,1′-dichloro substituted one 29b has shown that they are thermally unstable and only detectable below −100 ℃ by NMR spectroscopy (Chart 5).35) During the reduction of 20 with KC8 in THF at −78 ℃ (Scheme 2), an interesting spiropentasiladiene 30, a silicon congener of spiropentadiene, was isolated as a minor but thermally stable compound with mp 216–218 ℃.36)

Figure 2.

Schematic MO diagram for spiroconjugation for D2d (left) and D2 spiropenta(sila)dienes (right).

Chart 5.

The remarkable stability of spiropentasiladiene 30 is ascribed partly to much smaller strain energy (SE) of the silicon spiro-ring system than that of the carbon analog, in addition to the kinetic stability due to steric protection by four bulky tris(t-butyldimethylsilyl)silyl groups; the SE value of the parent spiropentasiladiene Si5H4 with D2d symmetry (61.1 kcal mol−1) calculated using homodesmic reactions at the B3LYP/6-311++G(3df,2p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) level is almost a half of that of the corresponding spiropentadiene C5H4 (D2d, 114.2 kcal mol−1).36) The large SE difference between C5H4 and Si5H4 is ascribed to the difference in the effects of the introduction of E=E double bonds into a small ring system; although the SE of cyclopropene (55.5 kcal mol−1) is almost twice of that of cyclopropane (25.8 kcal mol−1), the SE of cyclotrisilene (34.6 kcal mol−1) is even smaller than that of cyclotrisilane (35.4 kcal mol−1), being in accord with the flexible nature of the Si=Si double bond.

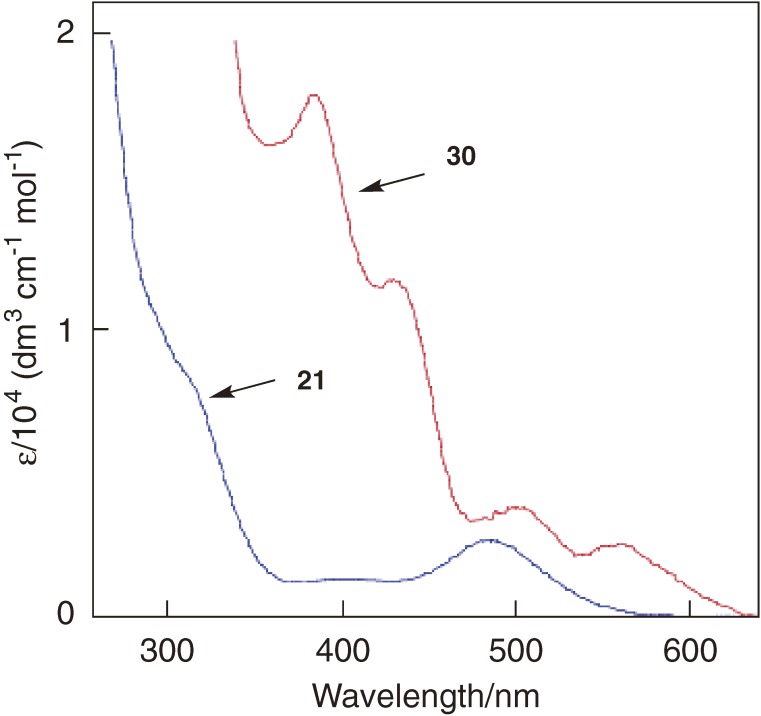

Because 30 is a sole stable spiropentadiene system known among its group-14 congeners, 30 serves as a probe to verify the theoretical spiroconjugation model. The structure of spiropentasiladiene 30 determined by X-ray crystallography shows however that the ring skeleton has D2 symmetry, where the two cyclopropene rings are not perpendicular to each other with the dihedral angle of 78.25° and the silicon atoms substituted at a cyclotrisilene ring are not coplanar with the ring plane.36) The distortion of a spiropentadiene from D2d to D2 requires modification of the previous theoretical model34) because through-space interaction between two bonding π orbitals is allowed in addition to that between π* orbitals, as shown in Fig. 2. The modified spiroconjugation model for a D2 spiropentadiene can be tested by comparing the UV-vis spectrum of 30 with that of reference cyclotrisilene 21. The UV-vis spectrum of 30 shows four π→π* bands at λmax/nm (ε/103) 560 (2.53), 500 (3.64), 428 (11.7), 383 (18.1), while only one π→π* band is observed at λmax/nm (ε/103) 482 (2.64) for 21 (Fig. 3). The spectral pattern with four distinct π→π* bands as well as the red shift of the longest wavelength band of 30 is not compatible with the simple model for a D2d spiropentadiene system but the modified model for a D2 spiropentadiene.

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectra of spiropentasiladiene 30 and cyclotrisilene 21 in hexane.

3. Trisilaallene and its germanium congeners

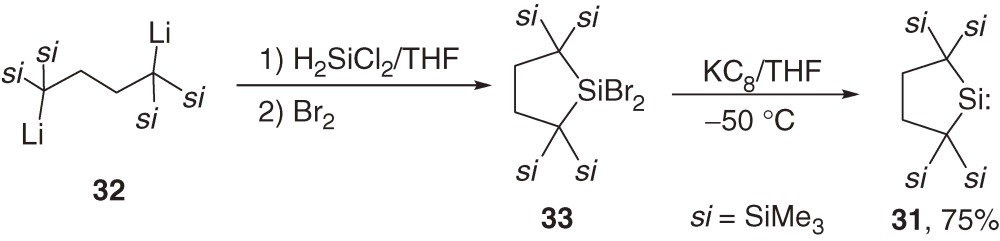

In 1999, we synthesized the first isolable dialkylsilylene 31 by the reduction of the corresponding dibromosilane 33, which was obtained by the reaction of 1,4-dilithiobutane 3237) with dichlorosilane followed by the bromination, using KC8 in a good yield (eq [13]).38) Because silylene 31 is divalent and highly reactive though it is sterically protected, versatile thermal and photochemical reactions of 31 have been observed.6a),39)

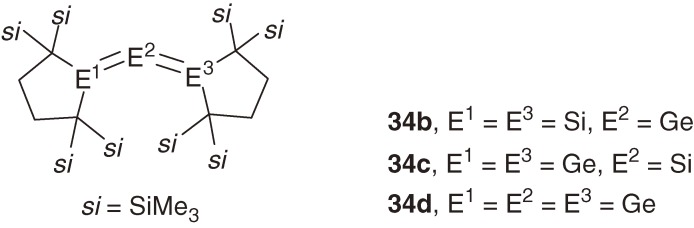

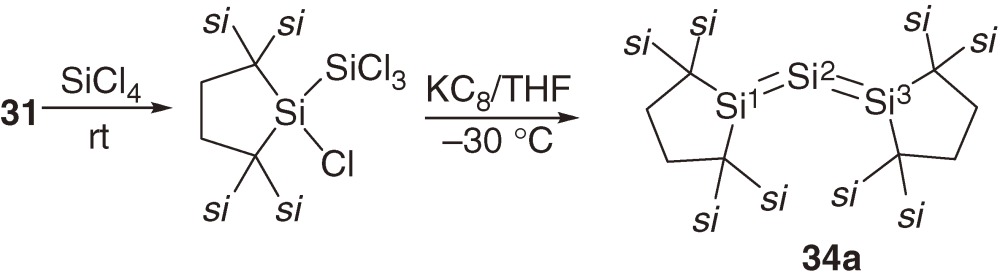

The first compound with cumulative Si=Si double bonds, trisilaallene 34a, was synthesized starting with stable silylene 31.40) The insertion of silylene 31 into a Si-Cl bond of tetrachlorosilane followed by the reduction with KC8 affords trisilaallene 34a as dark-green crystals (eq [14]). Related heavy allenes R2E=E′=ER2 (E, E′ = Si and Ge) 34b–34d are synthesized similarly (Chart 6).41)

Chart 6.

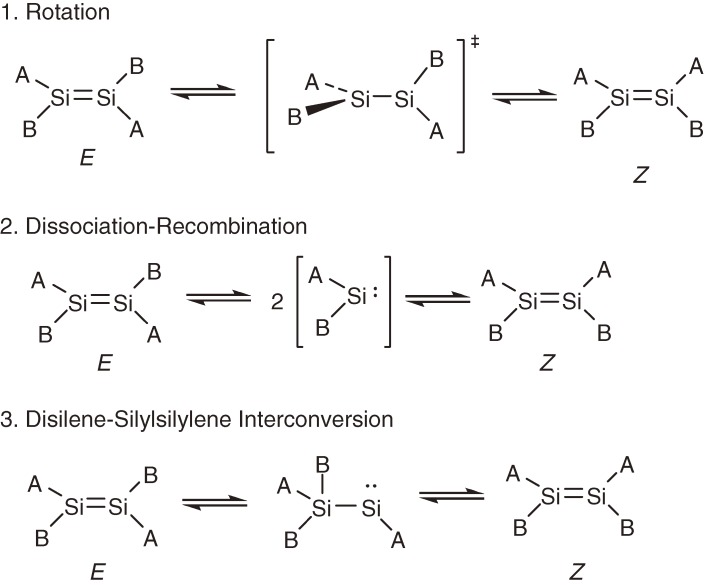

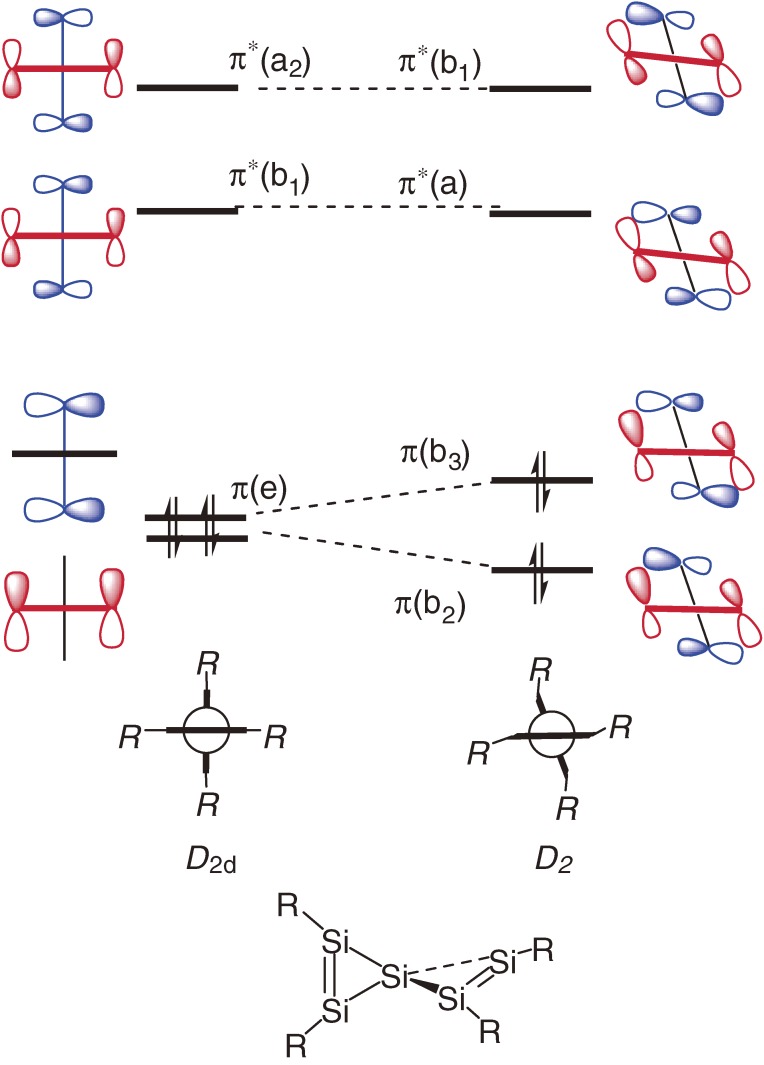

These heavy allenes are all thermally stable and stored under inert atmosphere but their structural characteristics are remarkably different from those of carbon allenes that have a rigid linear C–C–C skeleton and two orthogonal C–C π bonds.19a),40,41) The geometries of all the synthesized heavy allenes are not linear but bent with the E1–E2–E3 bond angles of 122–137°. Typically, the Si=Si double bond distance and the SiSiSi bond angle of trisilaallene 34a are 2.183(1) Å and 136.49(6)°, which are in good accord with the values calculated theoretically; they are 2.230 Å and 130.2° at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level,42) and 2.230 Å and 135.7° at the BP86/TZVPP level.43) The optimized geometry of relatively small trisilaallenes, H2Si=Si=SiH2 and Me2Si=Si=SiMe2, is quite different with a very narrow bend angle of around 70–90° and a small twist angle between two R2Si plane (R = H, Me)40,42,44) from that of synthesized trisilaallene 34a, and hence, the structural characteristics of the two types of heavy allenes should be discussed separately.

|

[13] |

|

[14] |

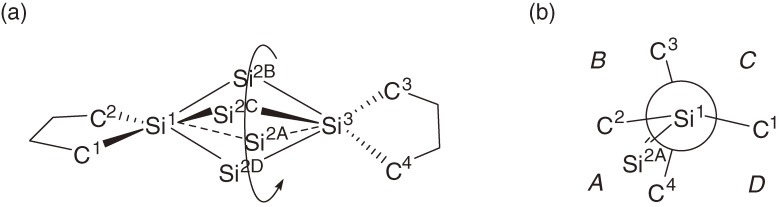

The bent skeletons of 34a–34d determined by X-ray crystallography are not rigid but fluxional both in the solid state and in solution (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

(a) A schematic representation of bent and fluxional characteristics of trisilaallene skeleton of 34a determined by X-ray crystallography. Central Si2 atom is disordered with occupancy at four positions Si2A to Si2D. (b) A Newmann-like projection along axis through Si1 and Si3 atoms. The Si2A to Si2D are located in quadrants A to D, respectively, which are separated by two silacyclopentane ring planes. The occupancy factor for Si2A to Si2D depends on temperature as well as the space area of the quadrant. The corresponding dihedral angles are 82.8, 92.1, 92.7, and 92.6° for Si2A to Si2D with the occupancy factors of 0.755, 0.175, 0.0, and 0.070 at −150 ℃.

The origin of the bent and fluxional skeleton of heavy allenes is ascribed to the Jahn-Teller distortion18) associated with the effective π-σ* orbital mixing, as schematically shown in Fig. 4.19a)) The π-σ* distortion (Section 1.4) is caused by the existence of a low-lying σ* orbital in heavy allenes stemming from the hybridization defects in heavy main group elements (Fig. 5). 5f),45) A more detailed discussion for the π-σ* distortion in heavy allenes is given in a full paper.19a))

Figure 5.

Schematic π-σ* orbital mixing diagram for the deformation of a linear D2d allene to a bent C2 allene. Degeneracy of π orbitals (πa and πb) in D2d is removed by the deformation to C2 allowing the interaction between πa-σa* interaction. The mixing coefficients c and c’ are small positive numbers. Atomic orbitals on E1 and E3 and those on E2 are shown in blue and red, respectively.

The 1H, 13C, and 29Si NMR spectra of 34a–34d are very simple and show that eight SiMe3 groups, four ring methylene groups, four ring quaternary carbon atoms, and two allenic terminal silicon atoms (if they exist) are equivalent, indicating the fluxional nature of the bent allenic structure in solution. The 29Si NMR chemical shifts of the allenic silicons for 34a are δ 196.9 (terminal) and δ 157.0 (central), which are consistent with those calculated for Me2Si=Si=SiMe2 with the bent structure determined by X-ray crystallography using the GIAO method at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2df,p)//B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level (δ 205.5 and δ 161.2, respectively).40)

The heavy allenes show at least two bands in the π→π* band regions of disilenes and digermenes. The longest band maxima [λmax/nm (ε)] of 34a–34d are remarkably red shifted from those of tetraalkyldisilenes (λmax = ca. 390 nm)46) and appear at around 584 (700), 599 (1100), 612 (3100), and 630 (5300), respectively, being indicative of significant conjugation between two double bonds of heavy allenes.

4. Other stable disilenes

4.1. Fused bicyclic disilene.

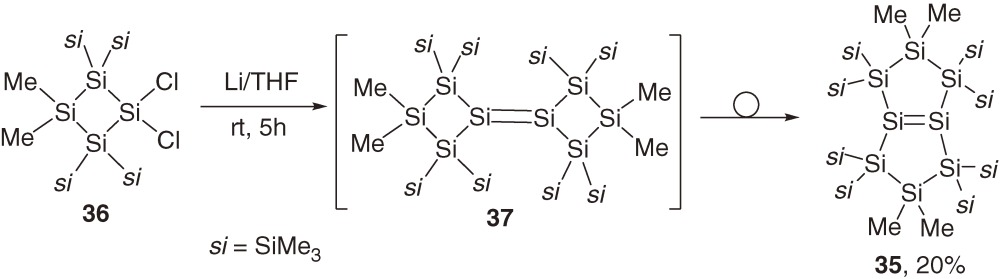

Fused bicyclic disilene 35 is synthesized by the reduction of 36 with lithium in THF at room temperature.47) Formation of 35 from monocyclic precursor 36 suggests that initial reductive coupling product 37 is highly strained and undergoes facile formal dyotropic rearrangement (Section 1.5) to give 35 as shown in eq [15].

|

[15] |

|

[16] |

|

[17] |

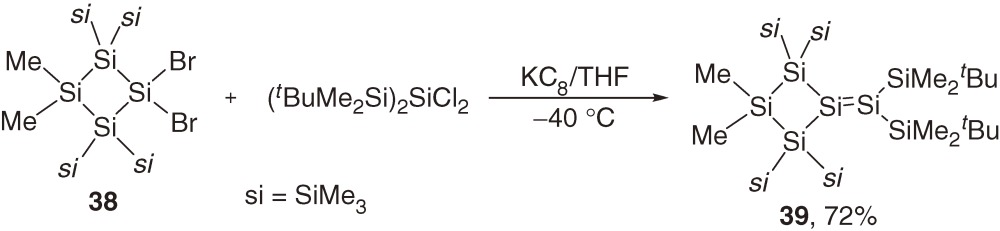

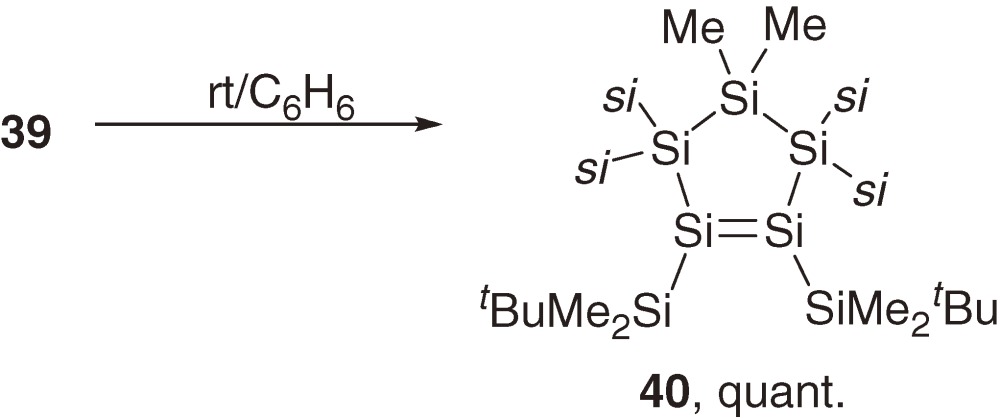

Although intermediate 37 is not detected during the reaction (eq [15]), the proposed pathway is supported by a study of a related reaction. Thus, a similar reaction of 38 with (tBuMe2Si)2SiCl2 at low temperature gives disilene 39 in a high yield (eq [16]). Disilene 39 isomerizes to cyclopentasilene 40 quantitatively at room temperature (eq [17]).48) Activation enthalpy (ΔH≠) and entropy (ΔS≠) for the first-order isomerization of 39 to 40 are determined to be 24.8 ± 1.0 kcal mol−1 and +6.5 ± 3.2 cal mol−1 K−1, respectively. The positive ΔS≠ is not compatible with the dyotropic rearrangement through a restricted transition state, suggesting preferable disilene-silylsilylene interconvertion via 1,2-silyl migration as discussed in Section 1.5.

|

[18] |

|

[19] |

|

[20] |

|

[21] |

Fused cyclic disilene 35 features topologically a partial structure of the Si(001) surface up to the third layer. The Si=Si double bond of 35, whose distance is 2.180(3) Å, adopts rather unusually a slightly cis-bent geometry with the bent angle of 3.6°, while all other disilenes whose structures were determined by X-ray analysis are trans-bent, twist, or planar. However, because the disilene moiety in the reconstructed Si(001) surface is known to have unsymmetric and significantly cis-bent structure,49) fused bicyclic disilene 35 is not yet an ideal model for the silicon surface.

4.2. Fused tricyclic disilenes.

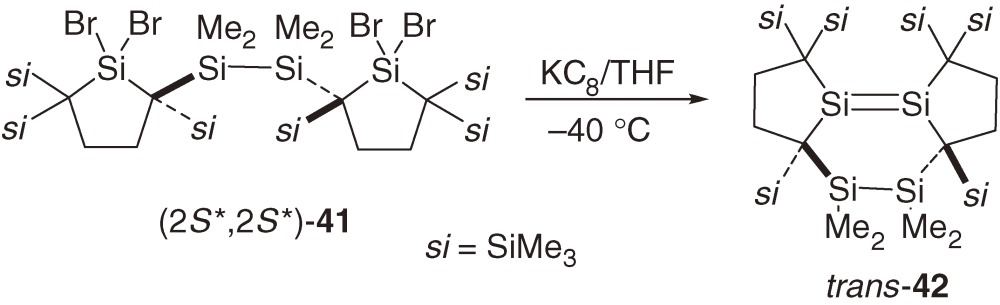

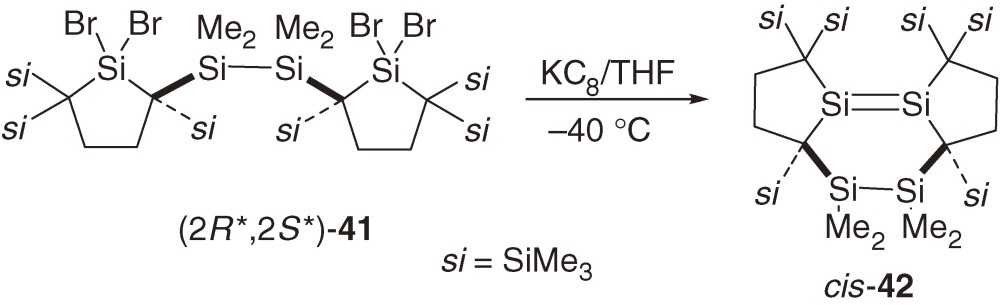

Dimerization of a silylene to the corresponding disilene and its reverse reaction constitute an important pair of chemical processes in organosilicon chemistry. Tetramesitylsilylene 7, the first stable silylene, was prepared by the dimerization of the corresponding silylene generated photochemically.2) Disilene 1623) and tetrakis(dialkylamino)disilene and a lattice-framework disilene designed by Sakamoto et al.50) dissociate into the corresponding two silylenes. Because dialkylsilylene 31 is sterically well protected and does not dimerize to the corresponding disilene either in solution or in the solid state, tethering two dialkylsilylene moieties may be possible to give a stable tethered bissilylene. However, the reduction of tetrabromides (2S*, 2S*)-41 and (2R*, 2S*)-41 with KC8 affords unexpectedly fused tricyclic disilenes trans-42 and cis-42, respectively (eqs [18] and [19]).51)

The geometry around the Si=Si bond in trans-42 is highly distorted with a central twist-boat six-membered ring. The Si=Si bond length of trans-42 (2.2687(7) Å) is much larger than those of usual stable disilenes (Table 2). The Si=Si bond in trans-42 adopts significantly trans-bent and twisted geometry with bend angles of 32.9 and 30.9° and a twist angle of 42.5°. Distortion around the Si=Si bond in cis-42 is relatively small with a boat six-membered ring; the Si=Si bond length, the bend angles, and the twist angle are 2.1767(6) Å, 3.9 and 12.4° at the two unsaturated Si atoms, and 3.9°, respectively.

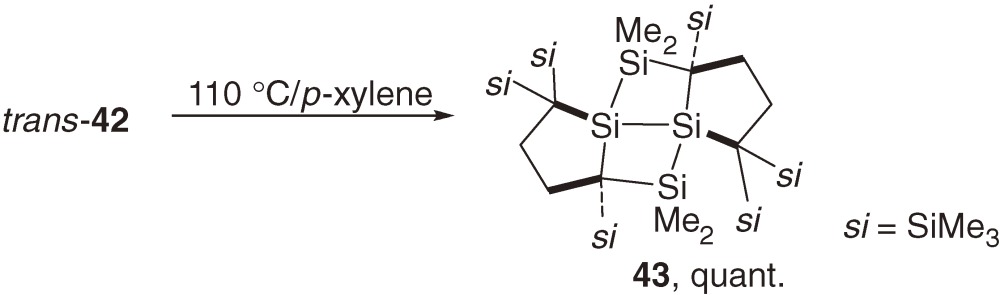

Neither cis-42 nor trans-42 dissociates into the corresponding bissilylene upon heating at 100 ℃ or upon irradiation with a Xe lamp. Highly distorted trans-42 undergoes unprecedented intramolecular [2s+2a] cycloaddition of the Si–Si single bond to the Si=Si double bond at 110 ℃ to give a tetracyclic compound 43 (eq [20]).

4.3. 1,2-Disilacyclohexene.

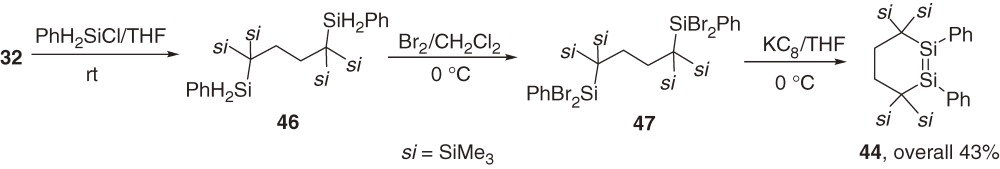

A novel type of stable six-membered cyclic disilene 4452) is synthesized as shown in eq [21] using a unique 1,4-dilithiobutane 32 that was applied for the synthesis of stable dialkylsilylene 31 (Section 3).37)

|

[22] |

|

[23] |

The X-ray analysis shows that the Si=Si double bond distance of 44 is rather normal with 2.1595(9) Å. The geometry around the double bond is slightly trans-bent and the six-membered ring adopts a conformation between an ideal chair and an ideal half-chair, which are known as the most stable conformations in all-carbon cyclohexane and cyclohexene, respectively.

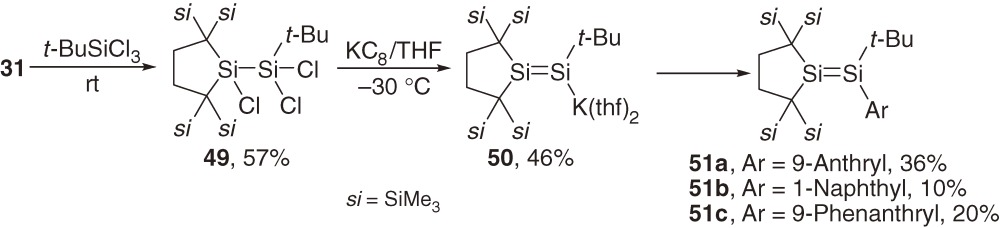

4.4. Aryltrialkyldisilenes.

Stable aryldisilenes are usually substituted by two to four aromatic groups, and hence, are not suitable for defining the nature of the electronic interaction between a disilene π and an aromatic π system (πSi-πC interaction). Using stable dialkylsilylene 31 (Section 3)38,39) as a key precursor, the synthesis of monoaryl-trialkyldisilenes allowing elucidation of the mode and extent of the πSi-πC interaction has been achieved.53) Prerequisite trialkyldisilenide 50 is obtained as single crystals by the reaction of trichlorodisilane 49 with KC8 in THF.54) Disilenes 51a–51c are synthesized by the reactions of 50 with the corresponding aryl bromides as air-sensitive colored crystals (eq [22]).

Molecular structures of disilenes 51a–51c determined by X-ray analysis feature trans-bent geometry around the Si=Si double bond. The Si=Si bond lengths [2.1754(12), 2.1943(14), and 2.209(2) Å for 51a–51c] are in the region of those for typical acyclic disilenes (Table 2). Disilene π (πSi) and aromatic π (πC) systems are almost perpendicular to each other with the dihedral angle of 88°, 83°, and 80° for 51a, 51b, and 51c.

No appreciable πSi-πC conjugative interaction is observed in 51a–51c because of the mutually perpendicular arrangement of the two π systems. However, anthryl-substituted disilene 51c with low-lying π* LUMO shows an unprecedented πSi→π*C intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) absorption bands at 520 nm (ε 420), suggesting the occurrence of the charge-transfer from a πSi donor to a πC acceptor system in certain circumstances.

4.5. Tetrasila-1,3-diene.

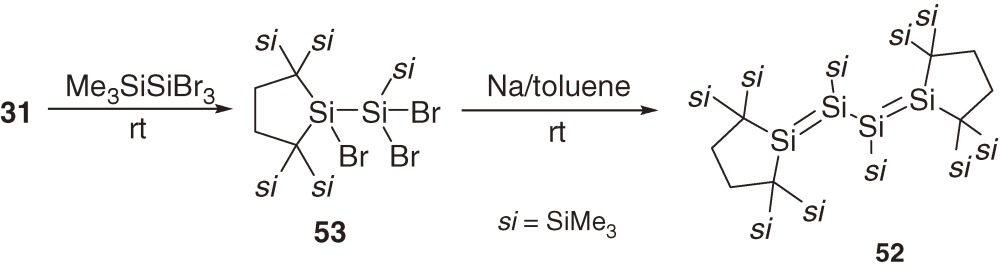

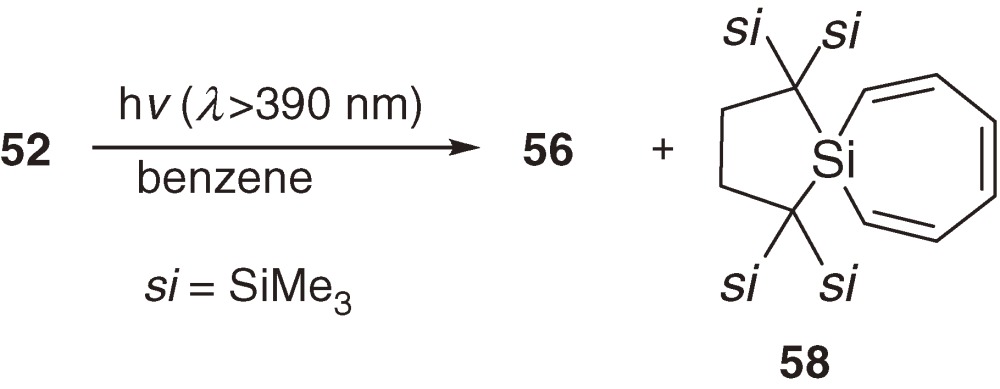

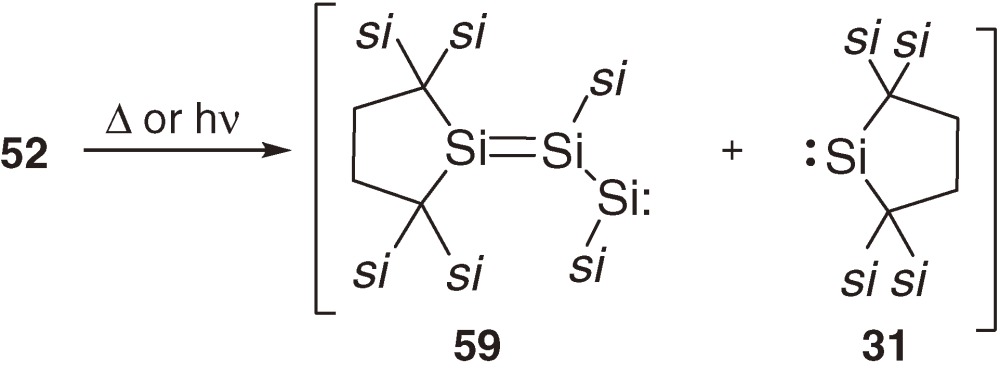

As a conjugated siladiene, tetrasila-1,3-diene 52 is synthesized as air-sensitive red crystals in 13% yield by the reaction of silylene 31 with Me3SiSiBr3 giving tribromodisilane 53 followed by the reduction with sodium metal in toluene at room temperature (eq [23]).55)

The Si=Si double bond distances of 52 in a crystal are 2.1980(16) and 2.2168(16) Å and the central Si-Si single bond distance is 2.3400(15) Å. The tetrasiladiene skeleton of 52 is not planar but highly twisted with an anticlinal conformation (the Si1-Si2-Si3-Si4 dihedral angle = 122.56(7)°), while known tetrasila-1,3-dienes 5456) and 5554b)) have a synclinal conformation (Chart 7).

Chart 7.

The longest wavelength absorption maximum of 52 is observed at 510 nm (ε 1200) at 77 K in a 3-methylpentane glass matrix and assignable to a π→π* transition band. The maximum is comparable to those of 54 (518 nm)56) and 55 (531 nm)54b)) even though no aromatic substituent is in 52, suggesting significant conjugation between the two π(Si=Si) systems. The 29Si NMR signals of central and terminal unsaturated Si nuclei of 52 appear at δ 9.3 and δ 210.2. Thermolysis of 52 at 80 ℃ in benzene gives cyclotrisilene 56 and cyclic silene 57 in high yields (eq [24]). Similarly, photolysis of 52 using a filtered high-pressure mercury arc lamp (λ > 390 nm) in benzene affords 56 and silacycloheptatriene 58 (eq [25]). Because 5738,57) and 5858) are known as major products of the thermal and photochemical reactions of silylene 31 in benzene, respectively, the initial step of these reactions should be the cleavage of a Si=Si double bond of 52 into 59 and 31 (eq [26]). Preferential cleavage of the Si=Si double bond to the central Si-Si single bond is a straightforward indication of the smaller bond dissociation energy of the double bond than that of the single bond in 52 as predicted by the CGMT model (Section 1.4).

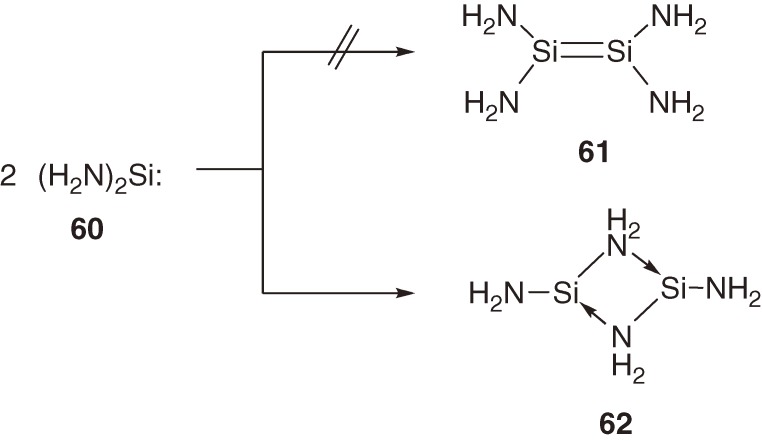

4.6. Tetraaminodisilenes.

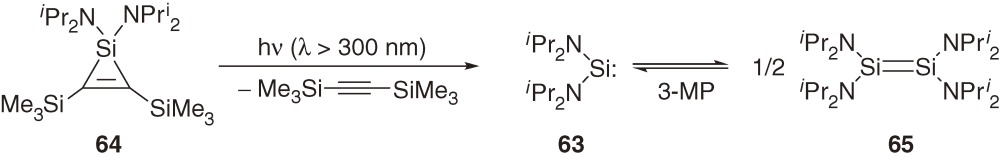

In accord with the CGMT model (Section 1.4), theoretical calculations have shown that dimerization of diaminosilylene (H2N)2Si: (60) with high ΔEST [79.3 kcal mol−1 at the B3LYP/6-311++G(3df,2p)//MP2/6-31G(d) level] does not form the corresponding disilene 61 but a four-membered cyclic bridged dimer 62 (Scheme 5).59,60) On the other hand, we have found that diaminosilylene 63 generated by the photolysis of silacyclopropene 64 is marginally stable in solution and dimerizes to the corrresponding disilene-type dimer 65 at low temperature (eq [27]).61) The temperature dependent equilibrium between 63 and 65 is observable UV-vis spectroscopically.

Scheme 5.

Apparent conflict in the dimerization mode between theoretical diaminosilylene 60 and the experimental diaminosilylene 63 is ascribed to the dependence of the ΔEST value on the dihedral angle between an n orbital on N and vacant pπ orbital on Si in (R2N)2Si:. The dihedral angle in silylene 63 is significantly increased by the steric effects of bulky isopropyl substituents, and hence, the ΔEST value is reduced to 54.3 kcal mol−1; the bridged dimer of 63 is higher in energy by 16.0 kcal mol−1 than the Si-Si bonded dimer 65.60) The geometry of tetraaminodisilene 65 calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level is very unusual with a dramatically long Si=Si distance of 2.472 Å, which is even longer than the Si-Si single bond (2.340 Å in Me3SiSiMe3); 65 is strongly pyramidalized around the silicon atoms with the bend angle of 42.6°.60)

5. Disilene transition metal complexes

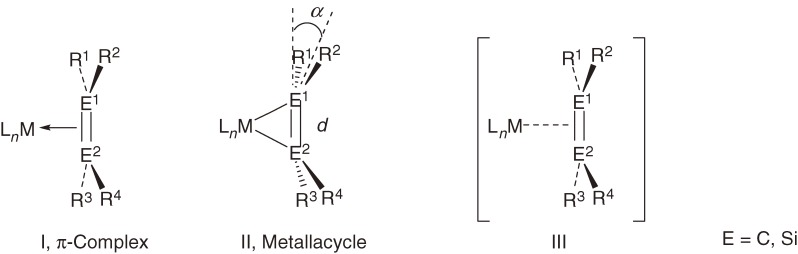

The bonding of an alkene to a transition metal center in a complex is usually understood in terms of alkene-to-metal σ-donation and metal-to-alkene π-back donation, according to the Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson model.62) The geometry around C=C double bond depends significantly on the relative importance of σ-donation and π-back donation; the complexes are classified into π-complexes (I) having a major contribution of σ-donation and metallacycles (II) having dominant π-back donation (Chart 8).63)

|

[24] |

|

[25] |

|

[26] |

|

[27] |

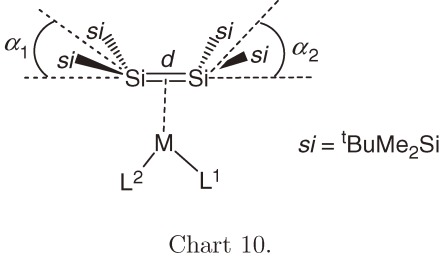

The geometry around the alkene ligand in the π-complex is not very much different from that of the planar free alkene, while that in the metallacycle is significantly distorted and characterized by an elongated C1–C2 bond length (d) and a large bent-back angle (α) defined as the angle between the R1–C1–R2 (or R3–C2–R4) plane and the C1–C2 bond (Chart 8, E = C). Ordinary alkene complexes have an intermediate character between π complex and metallacycle and often shown as a resonance between them. Hereafter, for descriptive purposes in this account, when the character of an alkene or disilene complex is not well known or is not needed to be considered, the structural formula is given as III with a dotted line between M and E=E bond (Chart 8).

Chart 8.

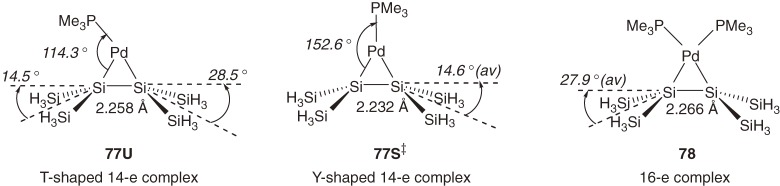

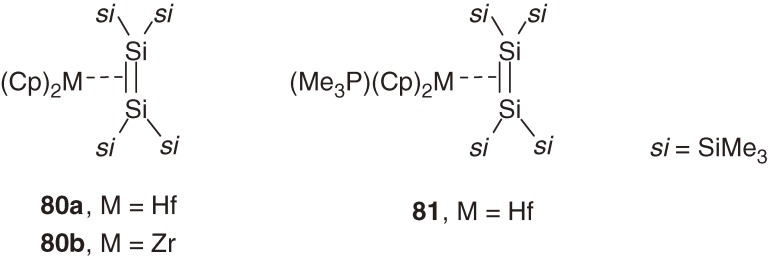

It is an interesting issue how the geometry around Si=Si bond is modified when a disilene coordinates to a transition metal. When we started a study in this direction, however, knowledge about the structure of η2-disilene metal complexes had been very limited. Among isolated mononuclear η2-disilene transition metal complexes 66a–66c,64) 67a–67b,64b)) and 68a–68b65) (Chart 9), only the structure of tungsten complex 68a65a)) with a character of metallacycle had been determined by X-ray crystallography. The structural issue of the disilene-metal complexes were first discussed theoretically by Sakaki et al.66) and Gordon et al.67) The ab initio MO calculations for (disilene)platinum complex 69a show that 69a features a large bent-back angle (α = ca. 25°), elongated Si-Si bond (Δd = 0.124 Å) and small Si-Si stretching force constant (3.08 mdyn Å−1 for disilene, while 2.63 mdyn Å−1 for 69a), and hence, 69a is characterized as a metallacycle.66)

Chart 9.

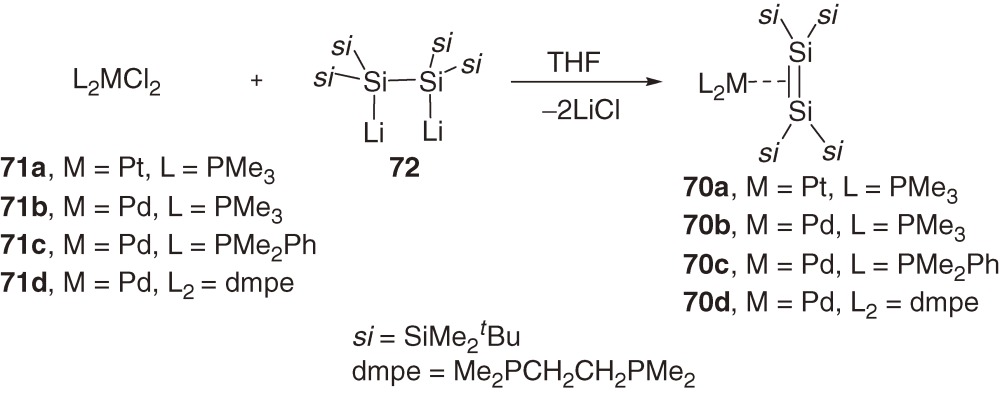

Various four-coordinate 16-electron palladium and platinum complexes 70a–70d68) with tetrakis(t-butyldimethylsilyl)disilene ligand (1a) are synthesized using the reactions of the corresponding dichlorobis(phosphine)metals 71a–71d with 1,2-dilithiodisilane 7269) (eq [28]).

|

[28] |

|

[29] |

|

[30] |

|

[31] |

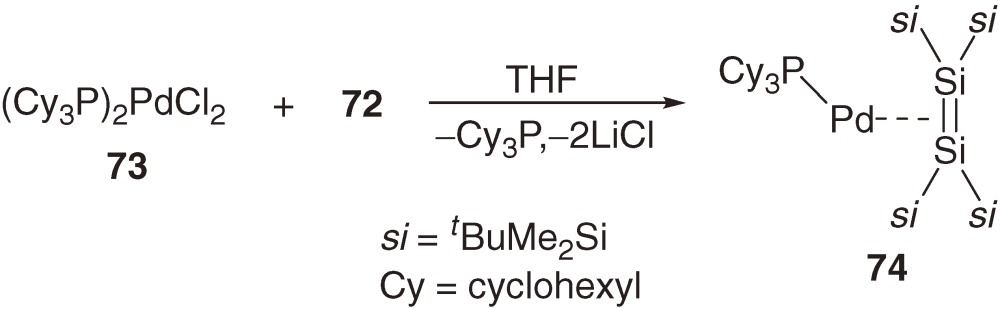

The reaction of bis(tricyclohexylphosphine)palladium dichloride 73 bearing bulky tricyclohexylphosphine ligands with dilithiodisilane 72 gives rather unusual three-coordinate 14-electron disilene-palladium complex 74 (eq [29]).70)

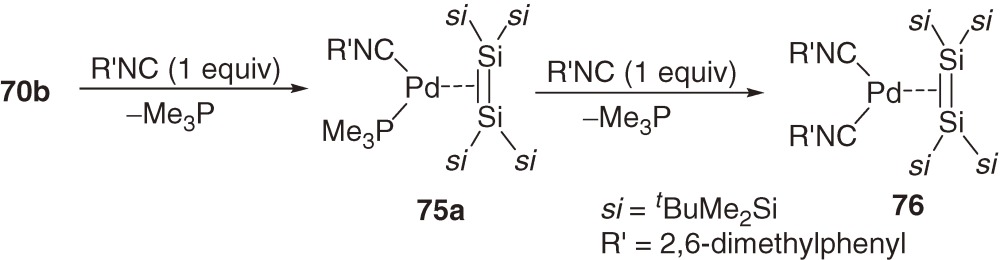

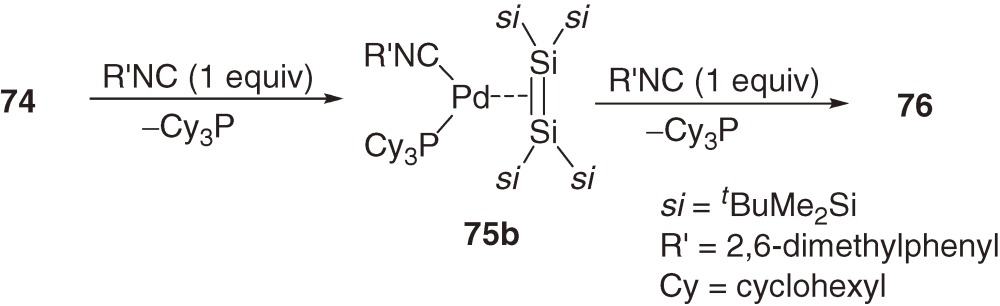

Related (disilene)palladium complexes with isocyanide ligands 75a, 75b, and 76 are synthesized by the reactions of 70b and 74 with the corresponding isocyanide (eqs [30] and [31]) in high yields.68c))

Recrystallization of (disilene)metal complexes 70a–70d, 74, 75b, and 76 gives single crystals suitable for X-ray structural analysis. The geometrical characteristics of these complexes are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of structural parameters of various (disilene)palladium complexesa

| Complexb | dc/Å | Δd/d0d (%) | α1 and α2e/° | δ(29Si)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70a, M = Pt, L1 = L2 = PMe3 | 2.322(2) | 5.4 | 29.3 | −79.7 |

| 70b, M = Pd, L1 = L2 = PMe3 | 2.3027(8) | 5.2 | 27.2 | −46.5 |

| 70c, M = Pd, L1 = L2 = PMe2Ph | 2.2952(13) | 4.2 | 14.4, 26.8 (av 20.6) | −44.8 |

| 70d, M = Pd, L1L2 = dmpe | 2.3180(8) | 4.2 | 27.3 | −51.9 |

| 75b, M = Pd, L1 = R’NC, L2 = PCy3g | 2.2861(11) 2.2967(11) av 2.291(6) | av 4.0 | 5.2, 20.6 3.0, 36.5 (av 16.3) | −39.4, −60.4 |

| 76, M = Pd, L1 = L2 = R’NC | 2.289(2) | 4.0 | 9.5, 8.9 (av 9.2) | −41.2 |

| 74, M = Pd, L1 = PCy3, L2 = none | 2.273(1) | 3.2 | 9.7, 4.4 (av 7.0) | +65.3 |

a) ref. 68c). b) Cy = Cyclohexyl, dmpe = 1,2-(dimethylphosphino)ethane, R’ = 2,6-dimethylphenyl. c) d is the Si=Si distance in complex in Å. d) d0 = d for 1a (2.202(1) Å); see Table 2. Δd/d0 (%) = (d for complex −d0) × 100/d0. e) Bend angles α1 and α2 are defined as angles between the Si=Si bond axis and si2Si planes that are trans to ligands L1 and L2, respectively. If the complex is symmetric, only one α is shown. f) 29Si NMR chemical shift for unsaturated silicon nuclei. g) Two crystallographically independent molecules are in an asymmetric unit.

If the Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson model62) is applicable to disilene complexes, the bent-back angle α and bond elongation Δd/d0 should decrease with increasing π-complex character of the disilene complexes. The α (°) and Δd/d0 (%) values for 16-electron Pt complex 70a are 29.3 and 5.4 and those for Pd complex 70b are 27.5 and 4.6, respectively. These values are the largest among disilene complexes shown in Table 3 and close to those observed for (disilene)tungsten complex 68a (α = 30.2° and Δd/d0 = 3.7%) and theoretical values for (H3P)2M(Si2H4) (M = Pt and Pd),66b)) and hence, complexes 70a and 70b are characterized as metallacycles, while the π-complex character of 70b seems slightly larger than that of 70a. On the other hand, the α and Δd/d0 values for 14-electron Pd complex 74 are much smaller than those of the 16-electron complexes.70) On this basis, complex 74 is regarded as the complex having the largest π-complex character among the disilene complexes.

Using α and Δd/d0 values, the π-complex character of complexes in Table 3 is evaluated to decrease in the following order: 74 > 76 > 75b (av.) > 70c > 70b∼70d > 70a. The π-back donation in 14-electron disilene complex 74 is the smallest because one basic ligand on palladium is missing. Because π-accepting ability of ligands is expected to increase in the order, Me3P < PhMe2P < R’NC on the basis of the basicity of the ligands, the π-back donation from the metal will increase in the order, 74 < 76 < 75b < 70c < 70b∼70d. Platinum has higher lying occupied d orbitals than palladium, and hence, the π-back donation from Pt would be larger than that from Pd (70b < 70a). The inverse order of the π-back donation is parallel to the observed order of the π-complex character of the disilene complexes, as expected.

Structural parameters of model 14-electron (disilene)palladium complex [77, (Me3P)Pd((H3Si)2Si=Si(SiH3)2)] and 16-electron (disilene)palladium complex [78, (Me3P)2Pd((H3Si)2Si=Si(SiH3)2)] calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G* for H, C, Si, and P and Lanl2DZ for Pd level70) are shown in Chart 11. The unsymmetrical (T-shaped) structure observed for 74 is well reproduced by the optimized unsymmetrical structure (77U), while the P–Pd–Si1 angle for 77U (114.3°) is significantly smaller than that observed for 74 (128.9°), probably due to the steric effects of bulky trialkylsilyl substituents in the latter.70) Unsymmetrical complex 77U is only 2.9 kcal mol−1 more stable than symmetrical (Y-shaped) complex 77S‡ that is found as a transition structure. Due to the intrinsic electron-deficient nature of the central metal of a 14-electron complex, π-back-bonding is much less effective in complex 77 than 16-electron complex 78.

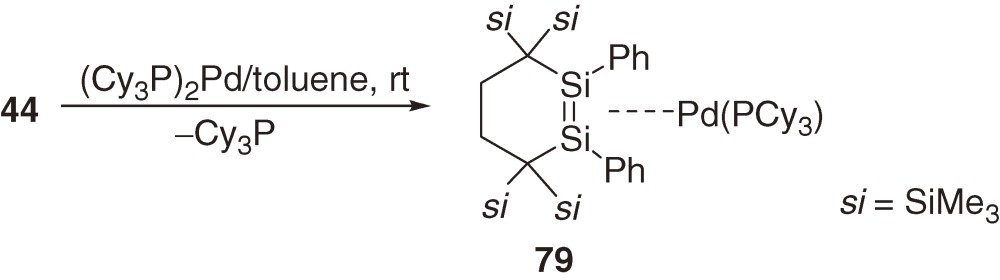

Chart 11.

A new 14-electron three-coordinated (disilene)palladium complex, 79, is synthesized by the reaction of cyclic disilene 44 (eq [21]) with (Cy3P)2Pd (eq [32]).52) Complex 79 is characterized as a Y-shaped tricoordinate complex with roughly symmetric coordination of the phosphine [the two P-Pd-Si angles in 79 are 142.66(2) and 151.48(2)°]. The θ (°) and Δd/d0 (%) values for 79 are 6.9 (average) and 1.9, which are both smaller than those for T-shaped 74 (Table 3), being indicative of larger π-complex character of the former. While the substituents around Si=Si bond are different between 74 and 79, the results support the theoretical prediction that, in a 14-electron three-coordinated disilene complex, Y-shaped complex has larger π-complex character than the corresponding T-shaped complex.

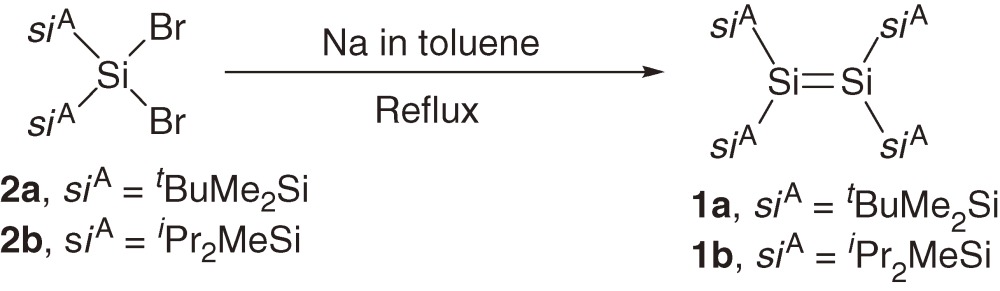

|

[32] |

The 29Si NMR resonance of 16-electron palladium complex 70b–70d is considerably higher field shifted than the corresponding free disilene (1a); ΔδSi [δSi(free disilene) − δSi(complex)] values for 70b and 70c are 188.9 and 186.9. On the other hand, the 29Si chemical shift for 14-electron complex 74 is δ +65.3 with ΔδSi value of 76.8 (Table 3). The remarkably lower field 29Si chemical shift of 74 would be another indication of its large π-complex character, in view of the difference in the 29Si NMR resonances between hexakis(trialkylsilyl)cyclotrisilanes (δ −174– −149)71) and free disilene 1a (δ +142.1).8a)) The 29Si NMR chemical shift for 79 is δ 40.2, which is even higher than that for complex 74 but the ΔδSi value for 79 (60.7) is significantly smaller than the ΔδSi value for 74, which is consistent with the larger π-complex character of 79 estimated by the structural parameters. Recently, Marschner et al. have reported more large difference in the 29Si NMR chemical shifts between disilene group-4 metal complexes 80 and 81 (Chart 12) with δ 132.8 for 80a and δ −135.7 and δ −159.7 for 81, suggesting remarkable variation in the bonding between disilene and metal.72)

Chart 12.

Concluding remarks

The chemistry of silicon multiply bonded compounds has rapidly evolved in these three decades. In addition to those discussed in this account, we have extended our studies to Si=C (silatriafulvenes73) and silaketeneimines74)) and Si=X (X = S, Se, Te75) and NR76)) compounds. Many silicon unsaturated compounds with novel types of bonding and structure including silabenzene,77) disilaacetylene,78) tetrasilacyclobutadiene,79) and silanone80) have been brought forth by other research groups. Their structural characteristics have been found often to be quite unique and far from the analogical extension of those of the carbon congeners.

The origin of the remarkable difference in the bonding and structure between carbon and heavier group-14 element compounds is usually ascribed to the less effective hybridization between s and p orbitals (hybridization defect) in the latter, in association with the fact that the difference in the radii between 2s and 2p orbitals of carbon is exceptionally small compared with that between valence ns and np orbitals of the heavier main group elements.5f),45) Although there is no doubt that the hybridization defect principle underlies the unusual properties of the heavier group-14 element compounds, it is hard to say currently that the principle is connected straightforwardly or logically to the unusual properties. As shown in this article, the π-σ* orbital mixing may be one of convincing rationales or concepts intervening between the hybridization defect and the unusual properties. Discovering and evaluating new such concepts will lead to construct a systematic and useful structural theory of heavier main-group elements.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks very much my former colleagues and students, especially Profs. T. Iwamoto, K. Sakamoto, W. Setaka and H. Hashimoto, and Dr. C. Kabuto for their active collaboration. All our studies have been performed with financial support from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. Writing this article was supported financially by the ministry (Grant-in Aid for Scientific Research (C) No. 22550028).

Profile

Mitsuo Kira was born in Higashiosaka City, Osaka in 1943. He graduated from Kyoto University, Faculty of Engineering in 1967 and started his research carrier at the laboratory of Prof. Makoto Kumada. After moving to Tohoku University, Faculty of Science, he received his D. Sc. degree from Tohoku University in 1974 under the guidance of Prof. Hideki Sakurai. He was appointed research associate, associate professor, and then full professor at Tohoku University during 1970–2007. He was an Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellow in the group of Prof. Hans Bock, Frankfurt University, Germany during 1977–1978 and a team leader at Photodynamics Research Center, Sendai, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN) during 1990–1998. After retiring from Tohoku University in 2007, he has held guest professorships in Tohoku University, Open University in Japan, and Key Laboratory of Organosilicon Chemistry and Material Technology of Chinese Ministry of Education, Hangzhou Normal University, China. His research interests include the chemistry of silicon and germanium compounds, physical organic chemistry, and organic photochemistry with particular focus on structure and reactivity of silicon unsaturated compounds including silylenes and disilenes, oligo- and polysilanes, hypercoordinate silicon compounds, and giant organosilicon compounds. He has been the recipient of The Chemical Society of Japan Award (2005), Wacker Silicone Award (2005), Japanese Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon (2007), The Society of Silicon Chemistry, Japan Award (2009), and F. S. Kipping Award from the American Chemical Society (2012) and was elected Fellow of The Chemical Society of Japan (2008).

References

- 1).(a) Gusel’nikov L.E., Nametkin N.S. (1979) Formation and properties of unstable intermediates containing multiple pπ-pπ bonded Group 4B metals. Chem. Rev. 79, 529–577; [Google Scholar]; (b) Jutzi P. (1975) New element-carbon (p-p)π bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 14, 232–245 [Google Scholar]

- 2).West R., Fink M.J., Michl J. (1981) Tetramesityldisilene, a stable compound containing a silicon-silicon double bond. Science 214, 1343–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Brook A.G., Abdesaken F., Gutekunst B., Gutekunst G., Kallury R.K. (1981) A solid silaethene: isolation and characterization. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 191–192 [Google Scholar]

- 4).(a) Selected reviews for silicon unsaturated bond compounds: Okazaki R., West R. (1996) Chemistry of stable disilenes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 39, 231–273; [Google Scholar]; (b) West R. (2002) Multiple bonds to silicon: 20 years later. Polyhedron 21, 467–472; [Google Scholar]; (c) Brook A.G., Brook M.A. (1996) The chemistry of silenes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 39, 71–158; [Google Scholar]; (d) Tsumuraya T., Batcheller S.A., Masamune S. (1991) Strained-ring and double-bond systems consisting of the group 14 elements Si, Ge, and Sn. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 30, 902–930; [Google Scholar]; (e) Rodi A.K., Ranaivonjatovo H., Escudié J., Kerbal A. (1996) Metallaimines >M=N-, metallaphosphenes >M=P- and metallaarsenes >M=As- (M: Si, Ge, Sn). Main Group Met. Chem. 19, 199–214; [Google Scholar]; (f) Escudie J., Ranaivonjatovo H. (1999) Doubly bonded derivatives of germanium. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 44, 113–174; [Google Scholar]; (g) Weidenbruch, M. (2001) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 3, Recent advances in the chemistry of silicon-silicon multiple bonds (eds. Rappoport, Z. and Apeloig, Y.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 391–428; [Google Scholar]; (h) Weidenbruch M. (2002) Some recent advances in the chemistry of silicon and its homologues in low coordination states. J. Organomet. Chem. 646, 39–52; [Google Scholar]; (i) Sekiguchi A., Ichinohe M., Kinjo R. (2006) The chemistry of disilyne with a genuine Si–Si triple bond: synthesis, structure, and reactivity. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 79, 825–832; [Google Scholar]; (j) Lee V.Y., Sekiguchi A. (2007) Aromaticity of group 14 organometallics: experimental aspects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 6596–6620; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Lee V.Y., Sekiguchi A., Escudié J., Ranaivonjatovo H. (2010) Heteronuclear double bonds E=E′ (E = heavy group 14 element, E′ = group 13–16 element). Chem. Lett. 39, 312–318; [Google Scholar]; (l) Tokitoh, N. and Okazaki, R. (1998) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 2, Recent advances in the chemistry of silicon-heteroatom multiple bonds (eds. Rappoport, Z. and Apeloig, Y.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 1063–1103; [Google Scholar]; (m) Okazaki R., Tokitoh N. (2000) Heavy ketones, the heavier element congeners of a ketone. Acc. Chem. Res. 33, 625–630; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Tokitoh N., Okazaki R. (2001) Recent advances in the chemistry of group 14-group 16 double bond compounds. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 47, 121–166; [Google Scholar]; (o) Tokitoh N. (2004) New progress in the chemistry of stable metallaaromatic compounds of heavier group 14 elements. Acc. Chem. Res. 37, 86–94; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Power P.P. (1999) π-Bonding and the lone pair effect in multiple bonds between heavier main group element. Chem. Rev. 99, 3463–3503; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (q) Power P.P. (2003) Silicon, germanium, tin and lead analogues of acetylenes. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2091–2101; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (r) Power P.P. (2007) Bonding and reactivity of heavier group 14 element alkyne analogues. Organometallics 26, 4362–4372; [Google Scholar]; (s) Fischer R.C., Power P.P. (2010) π-Bonding and the lone pair effect in multiple bonds involving heavier main group elements: developments in the new millennium. Chem. Rev. 110, 3877–3923; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (t) Müller, T., Ziche, W. and Auner, N. (2003) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 2, Silicon-carbon and silicon-nitrogen multiply bonded compounds (eds. Rappoport, Z. and Apeloig, Y.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 857–1062; [Google Scholar]; (u) Kira M., Iwamoto T. (2000) Stable cyclic and acyclic persilyldisilenes. J. Organomet. Chem. 611, 236–247; [Google Scholar]; (v) Kira M., Iwamoto T. (2006) Progress in the chemistry of stable disilenes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 54, 73–148 [Google Scholar]

- 5).(a) For reviews of theoretical studies of heavy group-14 unsaturated bond compounds, see: Apeloig, Y. (1989) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 1, Theoretical aspects of organosilicon compounds (eds. Patai, S. and Rappoport, Z.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 57–225; [Google Scholar]; (b) Scheldrick, W.S. (1989) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 1, Structural chemistry of organic silicon compounds (eds. Patai, S. and Rappoport, Z.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 227–303; [Google Scholar]; (c) Grev R.S. (1991) Structure and bonding in the parent hydrides and multiply bonded silicon and germanium compounds: from MHn to R2M=M′R2 and RM≡M′R. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 33, 125–170; [Google Scholar]; (d) Mackay, K.M. (1995) In The Chemistry of Organic Germanium, Tin and Lead compounds: Structural aspects of compounds containing C-E (E = Ge, Sn, Pb) bonds (eds. Patai, S. and Rappoport, Z.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 97–194; [Google Scholar]; (e) Karni, M., Kapp, J., Schleyer, P.v.R. and Apeloig, Y. (2001) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 3, Theoretical aspects of compounds containing Si, Ge, Sn, and Pb (eds. Rappoport, Z. and Apeloig, Y.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 1–164; [Google Scholar]; (f) Nagase, S. (1999) In The Transition State. A Theoretical Approach: Structures and reactions of compounds containing heavier main group elements. (ed. Fueno, T.). Kodansha, Tokyo, pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- 6).(a) For previous accounts, see: Kira M. (2004) Isolable silylene, disilenes, trisilaallene, and related compounds. J. Organomet. Chem. 689, 4475–4488; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kira, M., Iwamoto, T. and Ishida, S. (2005) In Organosilicon Chemistry VI-From Molecules to Materials: New molecular systems with silicon-silicon multiple bonds (eds. Auner, N. and Weis, J.). Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7).Prior to our works, Matsumoto, Nagai, et al. prepared tetrakis(triethylsilyl)disilene through a similar route to that shown in eq [5]. The disilene was rather stable in solution but could not be isolated: Matsumoto H., Sakamoto A., Nagai Y. (1986) The persilylcyclotrisilane [(Et3Si)2Si]3. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1768–1769 [Google Scholar]

- 8).(a) Kira M., Maruyama T., Kabuto C., Ebata K., Sakurai H. (1994) Stable tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)disilenes. Synthesis, X-ray structures, and remarkable substituent effects on electronic spectra. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 33, 1489–1491; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kira M., Ohya S., Iwamoto T., Ichinohe M., Kabuto C. (2000) Facile rotation around Si=Si double bonds in tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)disilenes. Organometallics 19, 1817–1819; [Google Scholar]; (c) Iwamoto T., Okita J., Kabuto C., Kira M. (2003) Synthesis, structure, and isomerization of A2Si=SiB2-type tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)disilenes. J. Organomet. Chem. 686, 105–111; [Google Scholar]; (d) Kira M., Iwamoto T., Maruyama T., Kabuto C., Sakurai H. (1996) Tetrakis(trialkylsilyl)digermenes. Salient effects of trialkylsilyl-substituents on planarity around Ge=Ge bond and remarkable thermochromism. Organometallics 15, 3767–3769; [Google Scholar]; (e) Iwamoto T., Okita J., Yoshida N., Kira M. (2011) Structure and reactions of an isolable Ge=Si doubly bonded compound, tetra(t-butyldimethylsilyl)germasilene. Silicon 2, 209–216 [Google Scholar]

- 9).Fink M.J., Michalczyk M.J., Haller K.J., Michl J., West R. (1984) X-ray crystal structures for two disilenes. Organometallics 3, 793–800 [Google Scholar]

- 10).Sekiguchi A., Inoue S., Ichinohe M. (2004) Isolable anion radical of blue disilene (tBu2MeSi)2Si=Si(SiMetBu2)2 formed upon one-electron reduction: synthesis and characterization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9626–9629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).West R., Cavalieri J.D., Buffy J.J., Fry C., Zilm K.W., Duchamp J.C., Kira M., Iwamoto T., Müller T., Apeloig Y. (1997) A solid-state NMR and theoretical study of the chemical bonding in disilenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 4972–4976 [Google Scholar]

- 12).(a) Liang C., Allen L.C. (1990) Group IV double bonds: shape deformation and substituent effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 1039–1041; [Google Scholar]; (b) Karni M., Apeloig Y. (1990) Substituent effects on the geometries and energies of the Si=Si double bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 8589–8590 [Google Scholar]

- 13).Shepherd B.D., Campana C.F., West R. (1990) Crystallographic analysis of thermochromic, unsolvated tetramesityldisilene at 173 K and 295 K. Heteroatom Chem. 1, 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 14).Hurni K.L., Rupar P.A., Payne N.C., Baines K.M. (2007) On the synthesis, structure, and reactivity of tetramesityldigermene. Organometallics 26, 5569–5575 [Google Scholar]

- 15).Schäfer H., Saak W., Weidenbruch M. (1999) Azadigermiridines by addition of diazomethane or trimethylsilyldiazomethane to a digermene. Organometallics 18, 3159–3163 [Google Scholar]

- 16).Igarashi M., Ichinohe M., Sekiguchi A. (2008) A stable silagermene (tBu3Si)2Si=Ge(Mes)2 (Mes = 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl): synthesis, X-ray crystal structure, and thermal isomerization. Heteroatom Chem. 19, 649–653 [Google Scholar]

- 17).(a) Carter E.A., Goddard III. W.A. (1986) Relation between singlet-triplet gaps and bond energies. J. Phys. Chem. 90, 998–1001; [Google Scholar]; (b) Trinquier G., Malrieu J.P. (1987) Nonclassical distortions at multiple bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 5303–5315; [Google Scholar]; (c) Malrieu J.P., Trinquier G. (1989) Trans-bending at double bonds. Occurrence and extent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 5916–5921; [Google Scholar]; (d) Trinquier, G. and Malrieu, J.-P. (1989) In The Chemistry of Functional Group, Supplement A. Vol. 2, Part 1: The chemistry of double-bonded functional group (ed. Patai, S.). Wiley, Chichester; [Google Scholar]; (e) Trinquier G. (1990) Double bonds and bridged structures in the heavier analogues of ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 2130–2137; [Google Scholar]; (f) Trinquier G., Malrieu J.P. (1990) Trans-bending at double bonds: scrutiny of various rationales through valence-bond analysis. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 6184–6196; [Google Scholar]; (g) See also Driess M., Grützmacher H. (1996) Main group element analogues of carbenes, olefins, and small rings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 36, 828–856 [Google Scholar]

- 18).Albright, T.A., Burdett, J.K. and Whangbo, M.-H. (1985) Orbital Interactions in Chemistry. Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 19).(a) Kira M., Iwamoto T., Ishida S., Masuda H., Abe T., Kabuto C. (2009) Unusual bonding in trisilaallene and related heavy allenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 17135–17144; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kira M. (2010) An isolable dialkylsilylene and its derivatives. A step toward comprehension of heavy unsaturated bonds. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 46, 2893–2903; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kira M. (2011) Distortion modes of heavy ethylenes and their anions: π-σ* orbital mixing model. Organometallics 30, 4459–4465 [Google Scholar]

- 20).Gobbi A., Frenking G. (1993) The singlet-triplet gap of the halonitrenium ions NHX+, NX2+ and the halocarbenes CHX, CX2 (X = F, Cl, Br, I). J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1162–1164 [Google Scholar]

- 21).Balasubramanian K. (1988) Relativistic configuration interaction calculations for polyatomics: Applications to PbH2, SnH2, and GeH2. J. Chem. Phys. 89, 5731–5738 [Google Scholar]

- 22).Schoeller W.W., Busch T. (1994) Electronic structure of the disilenyl radical anion. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 7, 251–255 [Google Scholar]

- 23).(a) Tokitoh N., Suzuki H., Okazaki R., Ogawa K. (1993) Synthesis, structure, and reactivity of extremely hindered disilenes: the first example of thermal dissociation of a disilene into a silylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 10428–10429; [Google Scholar]; (b) Suzuki H., Tokitoh N., Okazaki R., Harada J., Ogawa K., Tomoda S., Goto M. (1995) Synthesis and structures of extremely hindered and stable disilenes. Organometallics 14, 1016–1022; [Google Scholar]; (c) Suzuki H., Tokitoh N., Okazaki R. (1995) Thermal dissociation of disilenes into silylenes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 68, 2471–2481 [Google Scholar]

- 24).Reetz M. (1977) Dyotropic rearrangements and related σ-σ exchange processes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 16, 33–65 [Google Scholar]

- 25).(a) Yokelson H.B., Maxka J., Siegel D.A., West R. (1986) Silicon-29 NMR observation of an unprecedented rearrangement in tetraaryldisilenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108, 4239–4241; [Google Scholar]; (b) Yokelson H.B., Siegel D.A., Millevolte A.J., Maxka J., West R. (1990) 1,2-Diaryl rearrangement in tetraaryldisilenes. Organometallics 9, 1005–1010; [Google Scholar]; (c) Archibald R.S., van den Winkel Y., Powell D.R., West R. (1993) Linear 2,2-diaryl-substituted trisilanes: Structure and photolysis to disilenes. J. Organomet. Chem. 446, 67–72 [Google Scholar]

- 26).Kira M., Iwamoto T., Kabuto C. (1996) The first stable cyclic disilene: hexakis(trialkylsilyl)tetrasilacyclobutene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 10303–10304 [Google Scholar]

- 27).Iwamoto T., Kabuto C., Kira M. (1999) The first stable cyclotrisilene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 886–887 [Google Scholar]

- 28).A symmetric cyclotrisilene [(tBu2MeSi)4Si3] has been synthesized independently: Ichinohe M., Matsuno T., Sekiguchi A. (1999) Synthesis, characterization, and crystal structure of cyclotrisilene: A three-membered ring compound with a Si-Si double bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 38, 2194–2196. The cyclotrisilene features the Si=Si length of 2.138(1) Å, the longest absorption maxima at 469 nm (ε 440), and the 29Si NMR chemical shift of unsaturated silicon nuclei of 97.7 ppm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Iwamoto T., Tamura M., Kabuto C., Kira M. (2003) Photochemical isomerization and X-ray structure of stable [tris(trialkylsilyl)silyl]cyclotrisilene. Organometallics 22, 2342–2344 [Google Scholar]

- 30).(a) Woodward, R.B. and Hoffmann, R. (1970) The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry. Verlag-Chemie, Weinheim; [Google Scholar]; (b) Spellmeyer D.C., Houk K.N. (1988) Transition structures of pericyclic reactions. Electron correlation and basis set effects on the transition structure and activation energy of the electrocyclization of cyclobutene to butadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110, 3412–3416; [Google Scholar]; (c) Nguyen K.A., Gordon M.S. (1995) Isomerization of bicyclo[1.1.0]butane to butadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 3835–3847 and references cited therein; [Google Scholar]; (d) Leigh W.J., Postigo J.A., Venneri P.C. (1995) Orbital symmetry and the photochemical ring opening of cyclobutene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 7826–7827 [Google Scholar]

- 31).Müller, T. (2000) In Organosilicon Chemistry IV: The Si4H6 potential energy surface (eds. Auner, N. and Weis, J.). Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, pp. 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- 32).Iwamoto T., Kira M. (1998) A mechanistic study of thermal and photochemical isomerization between hexasilyltetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butane and hexasilyltetrasilacyclobutene. Chem. Lett. 277–278 [Google Scholar]

- 33).Uchiyama K., Iwamoto T., Kira M. Novel cyclotetrasilenes and their concerted isomerization into the corresponding bicyclo [1.1.0] tetrasilanes. to be published.

- 34).(a) Simmons H.E., Fukunaga T. (1967) Spiroconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89, 5208–5215; [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoffmann R., Imamura A., Zeiss G.D. (1967) The Spirarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89, 5215–5220; [Google Scholar]; (c) Dürr H., Gleiter R. (1978) Spiroconjugation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 17, 569–583 [Google Scholar]

- 35).(a) Billups W.E., Haley M.M. (1991) Spiropentadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 5084–5085; [Google Scholar]; (b) Saini R.K., Litosh V.A., Daniels A.D., Billups W.E. (1999) Synthesis and characterization of 1,4-dichlorospiropentadiene. Tetrahedron Lett. 40, 6157–6158 [Google Scholar]

- 36).Iwamoto T., Tamura M., Kabuto C., Kira M. (2000) A stable bicyclic compound with two Si=Si double bonds. Science 290, 504–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Kira M., Hino T., Kubota Y., Matsuyama N., Sakurai H. (1988) Preparation and reactions of 1,1,4,4-tetrakis(trimethylsilyl)butane-1,4-diyl dianion. Tetrahedron Lett. 29, 6939–6942 [Google Scholar]

- 38).Kira M., Ishida S., Iwamoto T., Kabuto C. (1999) The first isolable dialkylsilylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 9722–9723 [Google Scholar]

- 39).(a) For accounts of silylene 31, see: Kira M., Ishida S., Iwamoto T. (2004) Comparative chemistry of isolable divalent compounds of silicon, germanium, and tin. Chem. Rec. 4, 243–253; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kira M., Iwamoto T., Ishida S. (2007) A helmeted dialkylsilylene. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 80, 258–275; [Google Scholar]; (c) Kira M. (2010) An isolable dialkylsilylene and its derivatives. A step toward comprehension of heavy unsaturated bonds. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 46, 2893–2903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Ishida S., Iwamoto T., Kabuto C., Kira M. (2003) A stable silicon-based allene analogue with a formally sp-hybridized silicon atom. Nature 421, 725–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).(a) Iwamoto T., Masuda H., Kabuto C., Kira M. (2005) Trigermaallene and 1,3-digermasilaallene. Organometallics 24, 197–199; [Google Scholar]; (b) Iwamoto T., Abe T., Kabuto C., Kira M. (2005) A missing group-14 element trimetallaallene. 2-Germadisilaallene. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 5190–5192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Veszprémi T., Petrov K., Nguyen C.T. (2006) From silaallene to cyclotrisilanylidene. Organometallics 25, 1480–1484 [Google Scholar]

- 43).Takagi N., Shimizu T., Frenking G. (2009) Divalent silicon(0) compounds. Chemistry 15, 3448–3456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).(a) Kosa M., Karni M., Apeloig Y. (2004) How to design linear allenic-type trisilaallenes and trigermaallenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 10544–10545; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kosa M., Karni M., Apeloig Y. (2006) Trisilaallene and the relative stability of Si3H4 isomers. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2, 956–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).(a) Kutzelnigg W. (1984) Chemical bonding in higher main group elements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 23, 272–295; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kutzelnigg W. (1988) Orthogonal and non-orthogonal hybrids. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 169, 403–419; [Google Scholar]; (c) Kaupp M., Schleyer P.v.R. (1993) Ab initio study of structures and stabilities of substituted lead compounds. Why is inorganic lead chemistry dominated by PbII but organolead chemistry by PbIV? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 1061–1073 [Google Scholar]

- 46).(a) Sekiguchi A., Maruki I., Ebata K., Kabuto C., Sakurai H. (1991) High-pressure synthesis, structure and novel photochemical reactions of 7,7,8,8-tetramethyl-7,8-disilabicyclo[2.2.2]octa-2,5-diene. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 341–343; [Google Scholar]; (b) Masamune S., Eriyama Y., Kawase T. (1987) Synthesis and characterization of tetrakis[bis(trimethylsilyl)methyl]disilene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 26, 584–585 [Google Scholar]

- 47).Kobayashi H., Iwamoto T., Kira M. (2005) A stable fused bicyclic disilene as a model for silicon surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 15376–15377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Iwamoto T., Furiya Y., Kobayashi H., Isobe H., Kira M. (2010) Synthesis and facile ring expansion of silylenecyclotetrasilane. Organometallics 29, 1869–1872 [Google Scholar]

- 49).(a) Waltenburg H.N., Yates J.T. (1995) Surface chemistry of silicon. Chem. Rev. 95, 1589–1673; [Google Scholar]; (b) Konecny R., Hoffmann R. (1999) Metal fragments and extended arrays on a Si(100)-(2×1) surface. I. Theoretical study of MLn complexation to Si(100). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 7918–7924; [Google Scholar]; (c) Buriak J.M. (2002) Organometallic chemistry on silicon and germanium surfaces. Chem. Rev. 102, 1271–1308; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Choi, C.H. and Gordon, M.S. (2001) In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds. Vol. 3, Chemistry on silicon surfaces (eds. Rappoport, Z. and Apeloig, Y.). Wiley, Chichester, pp. 821–851; [Google Scholar]; (e) Yoshinobu J. (2004) Physical properties and chemical reactivity of the buckled dimer on Si(100). Prog. Surf. Sci. 77, 37–70 [Google Scholar]

- 50).(a) Matsumoto S., Tsutsui S., Kwon E., Sakamoto K. (2004) Formation of a stable, lattice-framework disilene: A strategy for the construction of bulky substituents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43, 4610–4612; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsutsui S., Tanaka H., Kwon E., Matsumoto S., Sakamoto K. (2004) Thermal equilibrium between a lattice-framework disilene and the corresponding silylene. Organometallics 23, 5659–5661 [Google Scholar]

- 51).Tanaka R., Iwamoto T., Kira M. (2006) Fused tricyclic disilenes with highly strained Si=Si double bonds: addition of a Si–Si single bond to a Si=Si double bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45, 6371–6373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Abe T., Iwamoto T., Kira M. (2010) A stable 1,2-disilacyclohexene and its 14-electron palladium(0) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5008–5009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Iwamoto T., Kobayashi M., Uchiyama K., Sasaki S., Nagendran S., Isobe H., Kira M. (2009) Anthryl-substituted trialkyldisilene showing distinct intramolecular charge-transfer transition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3156–3157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).(a) Two isolable disilenides with aromatic substituents have been reported: Scheschkewitz D. (2004) A silicon analogue of vinyllithium: structural characterization of a disilenide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 2965–2967; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ichinohe M., Sanuki K., Inoue S., Sekiguchi A. (2004) Disilenyllithium from tetrasila-1,3-butadiene: A silicon analogue of a vinyllithium. Organometallics 23, 3088–3090 [Google Scholar]