Abstract

Choledochal cysts are cystic dilation of extrahepatic duct, intrahepatic duct, or both that may result in significant morbidity and mortality, unless identified early and managed appropriately. The incidence is common in Asian population compared with western counterpart with more than two third of the cases in Asia being reported from Japan. The traditional anatomic classification system is under debate with more focus on etiopathogenesis and other aspects of choledochal cysts. Even though categorized under the same roof, choledochal cysts vary with respect to their natural course, complications, and management. In this review, with the available literature on choledochal cysts, we discuss different views about the etiopathogenesis along with the natural course, complications, diagnosis, and surgical approach for choledochal cysts, which also explains why the traditional classification is questioned by some authors.

Keywords: Etiopathogenesis, choledochal cysts, classification, excision, roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy

Choledochal cysts (CCs) are uncommon congenital anomalies of bile ducts with an incidence of 1 in 100,000–150,000 live births in the western population, but reported to be as high as 1 in 13,500 live births in the United States and 1 in 15,000 in Australia.[1] The incidence is higher in Asian population with an incidence of 1 in 1000, of which about two-third cases are reported from Japan.[2] CCs are usually diagnosed in childhood and about 25% are detected in adult life.[3] CCs also have an unexplained female:male preponderance, commonly reported as 4:1 to 3:1.[3] They are classified according to the location of biliary duct dilation as described by Todani et al.[4] Presentation is usually nonspecific and vague, especially in adults. Complications include pancreatitis, cholangitis, secondary biliary cirrhosis, spontaneous rupture of cyst, and cholangiocarcinoma. Improved imaging modalities have facilitated the diagnosis at any time from antenatal to adult life. Surgical management has evolved from cystenterostomy, which was associated with recurrence of symptoms and malignancy to primary cyst excision with roux-en-Y bilioenteric drainage either open or laparoscopic. Furthermore, a few type IVA and type V CC patients may need hepatic resection or liver transplantation.

CLASSIFICATION

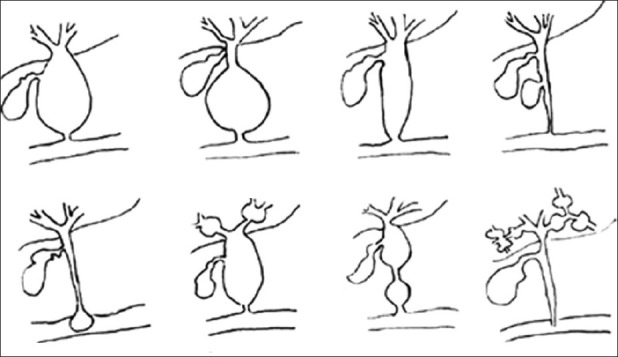

Initial classification by Alonso-Lej et al. in 1959 described 3 types of CCs, type I–III.[5] Later Todani et al. in 1977 modified it by adding type IV and V.[4] Modified Todani et al. classification is most commonly used by surgeons [Figure 1]. Type I CCs make up about 50%–80% of all CCs, type II 2%, type III 1.4%–4.5%, type IV 15%–35%, and type V 20%. Type I CCs are further subclassified into 3 types. Type IA is cystic dilation of entire extrahepatic biliary tree with sparing of intrahepatic ducts. Cystic duct and gall bladder arises from the dilated common bile duct (CBD). Type IB is focal, segmental dilation of extrahepatic biliary tree. Type IC is fusiform dilation of entire extrahepatic biliary tree extending into intrahepatic duct. Type II CCs are saccular diverticulum of the CBD. Type III CCs also termed choledochoceles, represents cystic dilation of intramural portion of distal CBD with bulge into the duodenum. Some authors contend it to be a duodenal diverticulum rather than CCs because of anatomic location and the duodenal epithelium they are lined by.[6] Ziegler et al. in their analysis of comparing choledochoceles to Todani types I, II, IV, and V, with respect to age, sex, complications, and management concluded that classification of CCs should not include choledochoceles.[7] Type IV CCs are further subclassified into type IVA and type IVB. Type IVA is the second most common CCs and is described by both intrahepatic and extrahepatic dilation of biliary ducts. Type IVB represents multiple dilation of extrahepatic biliary tree only. Type V CCs, known as Caroli's disease represents multiple dilation of intrahepatic biliary ducts. It is termed Caroli's syndrome when associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis, which then may present with cirrhosis and its manifestations.

Figure 1.

Modified Todani et al. classification of choledochal cyst

Lilly et al. described an entity called “forme fruste” CCs, where the patients present with typical symptoms of CCs and are associated with abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction (APBDJ) but without dilation of biliary ducts.[8] Sarin et al. believe this to be included under the spectrum of CCs.[9] Kaneyama et al. reported 4 cases of type II diverticulum arising from type IC CCs, which they termed as mixed type I and II CCs.[10] The incidence was 1.1% in their series of 356 cases. Four cases of diverticular cysts of cystic duct have been reported by Loke et al., which might be another variant of CCs.[11]

Visser et al. in their case series experienced all types of type I CCs had some element of intrahepatic dilation making them to contend type I and IVA cysts are variation of same disease and the degree of intrahepatic dilation defining one type versus the other was arbitrary.[12] They suggest a descriptive nomenclature for CCs challenging the Todani et al. classification, stating that traditional classification system is a group of separate disease entities with different etiologies, natural course, complications, and surgical options.

ETIOPATHOGENESIS

Etiology of CCs is an ongoing debate with both congenital and acquired theory supporters. The most commonly proposed theory is Babbitt's theory, where CCs are supposed to be caused by an APBDJ in which the pancreatic duct joins the bile duct 1–2 cm proximal to the sphincter of oddi.[13] The length of common channel varies from 10–45 mm with different authors. This long common channel allows pancreatic juice reflux into biliary system and cause increased pressure within the CBD resulting in ductal dilation.[14] This theory is supported by finding of high amylase levels in CCs bile.[15] Pancreaticobiliary reflux also leads to inflammation, epithelial breakdown, mucosal dysplasia, and malignancy. Few authors have also reported high trypsinogen and phospholipase A2 levels in CCs bile, which enhances the inflammation and bile duct breakdown.[16] But this theory is questioned by some authors because APBDJ is observed in only 50–80% cases of CCs, and CCs detected antenatally do not have pancreatic juice reflux and neonatal acini do not secrete sufficient pancreatic enzymes.[17] Obstruction of distal CBD is another theory, which is supported by studies on animal models.[18] Sphincter of oddi dysfunction reported in some studies may predispose to CCs.[19] This also results in pancreatic juice reflux into bile ducts. Kusunoki et al. proposed a pure congenital theory in which abnormally few ganglion cells are seen in distal CBD in patients with CCs resulting in proximal dilation in the same manner as achalasia of esophagus or Hirschsprung's disease.[20]

The above theories cannot explain type II CCs where the true diverticulum of CBD is associated with little inflammation and malignant potential. The question whether these are just biliary duplication cysts remains unanswered. Regarding choledochoceles, Wheeler suggested that obstruction of ampulla of Vater may result in localized dilation of distal intramural bile duct.[21] Since the lining of choledochoceles can be duodenal or biliary epithelium, some authors believe that these may be either duodenal or biliary duplication cysts.[22] The cause of Caroli's disease is unknown but may be associated with autosomal recessive inheritance and less commonly with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The likely mechanism involves an in vitro event that results in derangement in normal embryonic remodeling of ducts and causes varying degrees of destructive inflammation and segmental dilation of intrahepatic bile ducts.[23]

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CCs most commonly present in childhood and about 25% patients present in adulthood. The classic triad of symptoms, which includes pain abdomen, palpable abdominal mass, and jaundice, is seen in less than 20% of cases. An 85% of children have at least 2 features of classic triad, whereas only 25% of adults present with at least 2 features of the classic triad.[24] Neonates detected antenatally are usually asymptomatic at birth but it has to be intervened early before the onset of complications.

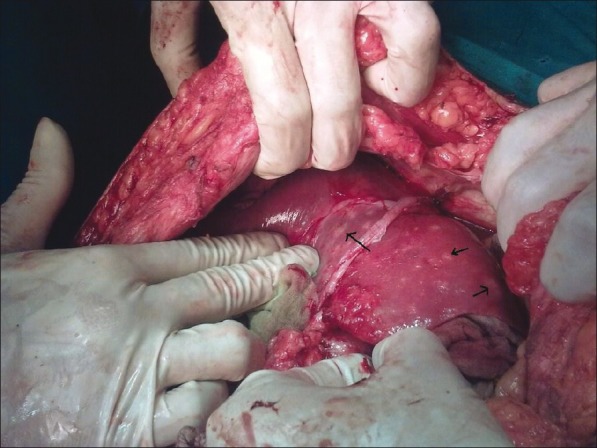

Dilated cysts and distal stricture due to chronic inflammation leads to bile stasis, which results in stone formation and infected bile, which in turn results in ascending cholangitis and further obstruction causing abdominal pain, fever, and obstructive jaundice. Chronic inflammation and formation of albumin-rich exudates or hypersecretion of mucin from dysplastic epithelium leads to protein plugs in pancreatic duct, which along with distal CBD stone causes pancreatitis.[25] Recurrent cholangitis seen in few cases of type IVA and Caroli's disease is due to bacterial colonization of intrahepatic dilations by the presence of bile stasis, sludge, and stones [Figure 2]. So in these cases anything short of total excision and liver transplantation results in lifelong complications, which may progress to liver abscess and life-threatening sepsis. Chronic obstruction may also result in secondary biliary cirrhosis. Samuel and Spitz reported biliary cirrhosis as the presenting feature in 10% of children in their series.[26] Nambirajan et al. reported 40–50% of cirrhosis in biopsies obtained during surgery.[27] Secondary biliary cirrhosis affects the outcome of surgery emphasizing the prompt early treatment of CCs. Martin and Rowe reported 6 cases of portal hypertension due to CCs causing either partial or complete obstruction of the portal vein.[28] Ando et al. reported 13 cases of spontaneous rupture of CCs resulting in biliary peritonitis.[29] The site of rupture is often at the junction of cystic duct and CBD as this is a site of poor blood flow. Type III CCs can cause gastric outlet obstruction by obstructing the lumen or by intussusception.

Figure 2.

Unilobar (left lobe) type IVA choledochal cysts with multiple chronic abscess (black arrows) of live

Malignancy

The increased risk of malignancy in CCs is well known. The reported incidence varies from 2.5% to 17.5% in patients with CCs. Visser et al. reported 21% in their series of 38 adult patients.[12] The incidence of malignancy increases with age, supposed to be 0.7% in the first decade of life to 14.3% after 20 years of age, which means early diagnosis and treatment has a favorable outcome. Malignancy occurs as a result of chronic inflammation, cell regeneration, and DNA breaks leading to dysplasia. Pancreatic reflux is also supposed to cause K-ras mutation, cellular atypia, P53 over expression, and carcinogenesis.[30] Malignancy is observed in extrahepatic duct in 50–62% patients, gall bladder in 38–46% cases, intrahepatic duct in 2.5% cases, and in liver and pancreas in about 0.7% cases. Todani et al. observed 68% of malignancy in type I, 5% in type II, 1.6% in type III, 21% in type IV, and 6% in type V CCs.[31] Malignancy occurs in 12-39% of “Forme Fruste” patients. Malignancy in CCs occurs in cysts and in “Forme Fruste” at the gall bladder. Malignancy in Caroli's disease is reported to be about 7–15% and in choledochoceles about 2.5%. Drainage procedure, such as cystenterostomy, and incomplete resection of cysts are associated with a high rate of malignancy. Liu et al. observed 33.3% malignancy in patients with incomplete cyst resection compared with 6% in complete cyst resection patients.[32] So patients who have undergone cystenterostomy in childhood should be advised for reoperation.

DIAGNOSIS

Blood investigations and imaging should be done in patients with clinical suspicion of CCs. Blood investigation may reveal altered liver function tests and leukocytosis in cholangitis due to CCs. Raised serum amylase and lipase indicates pancreatitis, while altered coagulation profile and kidney function tests may suggest the severity of the presentation. Raised CA 19-9 should raise the suspicion of malignancy in adults with CCs.

Imaging techniques confirm the diagnosis of CCs. Improved imaging techniques has made possible the diagnosis antenatally and also incidentally in adults. Radiographic visualization of both biliary system and pancreatic duct prior to surgery helps in complete excision of CCs. So the diagnostic workup should be done till enough information is available for operative planning.

Abdominal ultrasound (US) scan is the first step toward confirmation of diagnosis. Sensitivity of US is about 71–97%.[33] It is also the preferred investigation in postoperation surveillance. After a preliminary US scan, other supportive imaging techniques should be ordered to evaluate biliary system and pancreatic duct. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy using technitium-99 hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) has a sensitivity of 100% for type I CCs but sensitivity drops to 67% for type IVA CCs because of poor delineation of intrahepatic ductal dilation.[33] HIDA scan is useful to differentiate biliary atresia from CCs in the newborns. It can also diagnose spontaneous rupture of CCs where the dye will be seen entering the peritoneal cavity.

Computed tomography (CT) is highly accurate and also help in planning surgical approaches. It delineates well the intrahepatic biliary dilation in type IVA and Caroli's disease and also the extent of intrahepatic dilation, which helps in surgical planning, such as segmental lobectomy, in case of localized intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation. CT can also identify cyst wall thickening due to malignancy. Computed tomographic cholangiopancreatography (CTCP) is used to delineate the biliary tree and has a sensitivity of 93% for visualization of biliary tree, 90% sensitivity for diagnosing CCs, and 93% sensitivity for detecting stones. Lam et al. observed equally good results with both CTCP and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in diagnosing CCs in 14 children.[34] But CT and CTCP have nephro- and hepatotoxicity due to contrast along with radiation exposure. CTCP is shown to be better than MRCP in delineating bilioenteric anastomosis postoperatively.

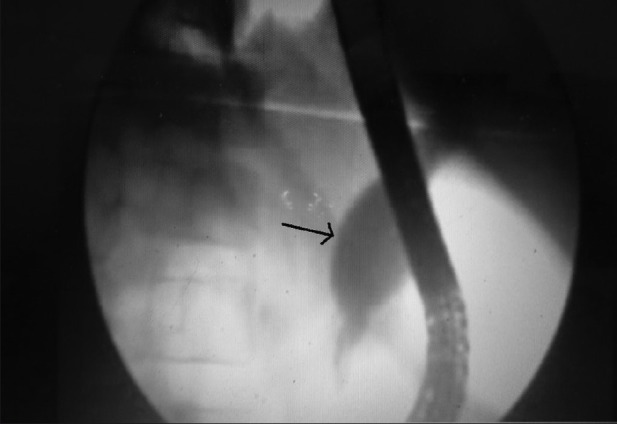

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is reported to be the most sensitive diagnostic modality for CCs [Figure 3]. But the sensitivity decreases in case of recurrent inflammation and scarring where the procedure becomes difficult. It is an invasive procedure, which may cause cholangitis and pancreatitis, and these complications are reported to be higher in CCs patients when compared with other patients because of dilated ducts, long common channel, and sphincter of oddi dysfunction. ERCP in CCs also need large amount of dye to fill cyst, which increases the chance of cholangitis and pancreatitis.[35] ERCP also exposes the patients to risks of radiation.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showing type I choledochal cyst (black arrow)

In view of the above reasons, MRCP is regarded as the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of CCs [Figure 4]. Sensitivity has been reported to be as high as 90–100%.[36] But sensitivity for delineating pancreatic duct and common pancreaticobiliary channel is 46%, which is less when compared with CTCP whose sensitivity for the same is 64%. MRCP avoid ionizing radiation and is also noninvasive when compared with ERCP with no complications of pancreatitis or cholangitis. MRCP with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also image surrounding structures, stones, and malignancy.

Figure 4.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing type IVA choledochal cys

Type III CCs may need multiple modalities before making a diagnosis. Upper gastrointestinal series may show a filling defect due to bulge into duodenal lumen. Endoscopy and ERCP demonstrates bulging and also dilated intramural CBD. ERCP is the choice of imaging modality in choledochoceles because therapeutic sphincterotomy can be done at the same time.[37] Caroli's disease can be diagnosed in US scan, CT, and MRI scan where it is seen as multiple intrahepatic dilations. CT and MRI also identify stones, associated cirrhosis, and portal hypertension, varices, liver abscess, and malignancy. The “central dot” sign, which is a dilated duct surrounded by portal bundle can be seen in US scan, CT, and MRI scan.

MANAGEMENT

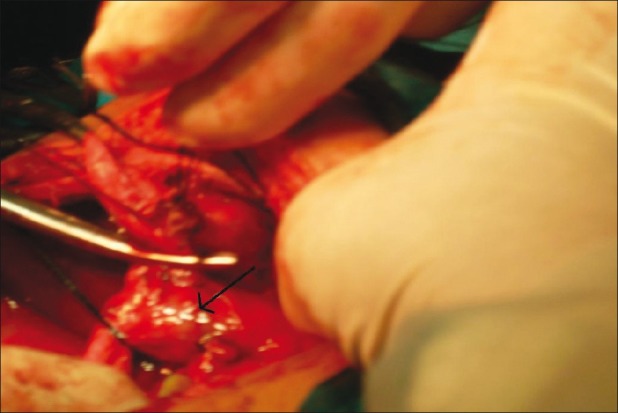

In search of the best procedure for the management of CCs, surgery has undergone a lot of development. Historically, cystenterostomy was considered the surgical method of choice for CCs. Later studies proved that cystenterostomy itself was associated with recurrence of symptoms and also high risk of malignancy in the remaining cyst wall. Visser et al. observed malignancy in 30% of adult patients who had previously undergone cystenterostomy for CCs.[12] So complete excision of the cyst and biliary diversion is the surgery of choice for CCs [Figure 5]. The patients who had undergone previous cystenterostomy should be reoperated for complete resection of cyst and biliary diversion as early as possible. Chaudhary et al. in their review with patients who had undergone internal or external drainage for CCs previously suggested that reoperation is possible in these patients and external drainage can be preferred as an initial procedure in severely ill patients.[38] External drainage can be via “T” tube or percutaneous hepaticostomy. This is true, especially in case of spontaneous rupture of CCs where the patients are initially stabilized by peritoneal lavage, external drainage via T tube before definitive procedure.

Figure 5.

Peroperative picture of type I choledochal cyst (black arrow)

Biliary diversion after excision can be done by hepaticodu-odenostomy (HD),hepaticoappendicoduodenostomy, or hepaticojejunostomy.

There are conflicting results about hepaticoduodenostomy in the literature. Shimotakahara et al. in their report on 28 cases of roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (RYHJ) and 12 HD concluded that HD in not ideal for biliary reconstruction in CCs because of a high incidence of complications (33%) due to duodenogastric bile reflux.[39] Elhalaby et al. opines that HD may be preferred due to shorter operative time and avoidance of intestinal anastomosis but more patients with HD are required before reaching a solid conclusion.[40] Recently Liem et al. reported their experience of laparoscopic HD in 74 patients, in which cholangitis was observed in 3 patients (5.3%) and gastritis due to bile reflux in 8 patients (14.3%).[41] However, the followup period was just between 3 months and 1 year. Although they opine it to be a safe and physiologic procedure, long-term results are awaited for better conclusions. Therefore, more evidence is needed to accept HD as a favored procedure.

Wei et al. also proposed the method of using appendix with its vascularized pedicle as the conduit between hepatic ducts and duodenum, but the procedure has not gained much popularity because of its complexity and also it was observed that appendix graft undergoes stenosis, resulting in hepatic fibrosis.[42]

Complete excision of the cyst and RYHJ is now considered the surgery of choice in most of the CCs. Resection includes from the bifurcation of lobar hepatic ducts into parenchyma of pancreas nearer to the junction of pancreatic duct. Tao et al. suggested minimum diameter of stoma to be 3 cm and observed 92% success rate with RYHJ.[43] Even RYHJ is associated with complications, such as cholangitis, pancreatitis, biliary calculi, and malignancy. These complications are usually seen in patients operated at later age because of fibrosis and inflammation of cyst tissue at the time of surgery.[44] Watanabe et al. reported <1% malignancy is patients who had undergone cyst excision previously.[45] But the incidence varies from 0.7% to 6% and in most cases it is due to incomplete cyst excision. This emphasizes the need for preoperative planning for complete excision of the cyst.

Sharma et al. reviewed 35 patients who were operated previously for CCs with different procedures, such as RYJH (26 patients), hepaticoduodenostomy (5 patients), cystoduodenostomy (2 patients), and external drainage in 3 patients. They opined that RYHJ is the “gold standard” procedure for CCs, but other surgical interventions also play a significant role in various situations.[46]

The surgical approach in type IVA is still debatable. Visser et al. suggested excision of extrahepatic component only with hepaticojejunostomy in case of type IVA CCs irrespective of the changes.[12] However, in case of extensive intrahepatic dilation with complications, such as stones, cholangitis, or biliary cirrhosis, other options, such as hepatic resection in case of unilobar disease [Figure 6] and liver transplantation in bilobar disease should be considered.

Figure 6.

Left hepatectomy for left lobar type IVA choledochal cysts. Also multiple stones (black arrow) are seen in bile duct cys

Nowadays, cyst excision and RYHJ are also done laparoscopically. Jeffrey et al., in their review of 13 pediatric patients, concluded that laparoscopic resection of CCs with total intracorporeal reconstruction of biliary drainage is a safe and effective technique.[47] Palanivelu et al. reported the largest series on laparoscopic treatment of CCs in adults. In their review of 35 patients, including 16 adults, they found that laparoscopic surgery for CCs is safe, feasible, and advantageous.[48] Liem et al. have reported their experience with 74 cases of laparoscopic HD for CCs and have opined it to be a safe and physiologic procedure.[41] But the long-term implications of laparoscopic surgery is yet to be reported and controlled trials comparing the open and laparoscopic approach is yet to be reported.

Type II CCs are managed by simple excision. Usually these cysts are ligated at the neck and excised without the need for bile duct reconstruction. Type III CCs were historically treated by transduodenal excision and sphincteroplasty. But recently endoscopic sphincterotomy is accepted to be sufficient treatment but patient should be under endoscopic surveillance since malignancy has been reported in choledochoceles. Ohtsuka et al. observed malignancy in 3 of 11 patients with choledochoceles.[49] In Caroli's disease, when the intrahepatic duct dilation is localized and without congenital hepatic fibrosis, segmental hepatectomy can be done.[50] Percutaneous or endoscopic drainage and stent are used for palliative treatment. For diffuse disease with life-threatening complications, liver transplantation should be considered. In a review of 110 cases of liver transplantation for Caroli's disease or syndrome, a 5-year patient and graft survival was observed to be 86% and 71%, respectively.[51]

CONCLUSION

Clinical suspicion of CCs should be followed by early diagnosis and management in view of life-threatening complications and high risk of malignancy. Later the diagnosis worse will be the prognosis. The current system of anatomic classification has to be re-evaluated as different types of CCs vary with respect to their etiology, malignant potential, diagnosis, and management. APBDJ, distal CBD obstruction, and sphincter of oddi dysfunction are proposed to be the etiologic factors. MRCP is the imaging modality of choice except in choledochoceles, which needs multiple imaging modalities before diagnosis. A complete excision of the extrahepatic system and RYHJ is the treatment of choice in type I and most of type IV CCs. Case series on laparoscopic CCs excision and bilioenteric drainage has been reported but needs controlled trials and long-term results are awaited. Internal or external drainage of cysts should be considered only in case of emergency and as a palliative procedure. Patients who had previously undergone cystenterostomy should undergo reoperation for complete cyst excision and RYHJ. Type II cysts need simple cyst excision, whereas choledochoceles are managed by endoscopic sphincterotomy with a follow-up endoscopic surveillance. Few cases of localized intrahepatic type IVA CCs and Caroli's disease with complications should be considered for hepatic resection. Diffuse intrahepatic disease with complications in type IVA and Caroli's disease should be offered liver transplantation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gigot J, Nagorney D, Farnell M, Moir C, Ilstrup D. Bile duct cysts: A changing spectrum of disease. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1996;3:405–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill JA., Jr Choledochal cyst. Curr Probl Surg. 1992;29:361–410. doi: 10.1016/0011-3840(92)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Lam CM, Poon RT, Wong J. Choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2002;137:465–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso-Lej F, Rever WB, Jr, Pessagno DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and an analysis of 94, cases. Int Abstr Surg. 1959;108:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorenstein L, Strasberg SM. Etiology of choledochal cysts: Two instructive cases. Can J Surg. 1985;28:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler KM, Pitt HA, Zyromski NJ, Chauhan A, Sherman S, Moffatt D, et al. Choledochoceles: Are they choledochal cysts? Ann Surg. 2002;252:683–90. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f6931f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lilly JR, Stellin GP, Karrer FM. Forme fruste choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:449–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(85)80239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarin YK, Sengar M, Puri AS. Forme fruste choledochal cyst. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:1153–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneyama K, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Mixed type I and II choledochal cyst: A new clinical subtype? Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:911–3. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loke TK, Lam SH, Chan CS. Choledochal cyst. An unusual type of cystic dilatation of the cystic duct. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:619–20. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.3.10470889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visser BC, Suh I, Way LW, Kang SM. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2004;139:855–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.8.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babbitt DP. Congenital choledochal cyst: New etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1969;12:231–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwai N, Yanagihara J, Tokiwa K, Nakamura K. Congenital choledochal dilatation with emphasis on pathophysiology of the biliary tract. Ann Surg. 1992;215:27–30. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama M, Haradome H, Takahara T, Izumisato Y, Abe N, Masaki T, et al. Biliopancreatic reflux via anomalouspancreaticobiliary junction. Surgery. 2004;135:457–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada A, Hasegawa T, Oguchi Y, Nakamura T. Recent advances in pathophysiology and surgical treatment of congenital dilatation of the bile duct. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:342–51. doi: 10.1007/s005340200038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imazu M, Iwai N, Tokiwa K, Shimotake T, Kimura O, Ono S. Factors of biliary carcinogenesis in choledochal cysts. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001;11:24–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitz L. Experimental production of cystic dilatation of the common bile duct in neonatal lambs. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(77)90293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponce J, Garrigues V, Sala T, Pertejo V, Berenguer J. Endoscopic biliary manometry in patients with suspected sphincter of oddi dysfunction and in patients with cystic dilatation of the bile ducts. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:367–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01536257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusunoki M, Saitoh N, Yamamura T, Fujita S, Takahashi T, Utsunomiya J. Choledochal cysts oligoganglionosis in the narrow portion of the choledochus. Arch Surg. 1988;123:984–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400320070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wheeler W. An unusual case of obstruction of the common bile duct (choledochocele.)? Br J Surg. 1940;27:446–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagiyama S, Okazaki K, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto Y. Anatomic variants of choledochocele and manometric measurements of pressure in the cele and the orifice zone. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:641–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy AD, Rohrmann CA, Jr, Murakata LA, Lonergan GJ. Caroli's disease: Radiologic spectrum with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1053–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.4.1791053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL. Choledochal cyst disease a changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:644–52. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano K, Mizuta A, Oohashi S, Kuroki S, Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M, et al. Protein stone formation in an intrapancreatic remnant cyst after resection of a choledochal cyst. Pancreas. 2003;26:405–7. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200305000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuel M, Spitz L. Choledochal cyst: Varied clinical presentations and long-term results of surgery. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996;6:78–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1066476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nambirajan L, Taneja P, Singh MK, Mitra DK, Bharnagar V. The liver in choledochal cyst. Trop Gastroenterol. 2000;21:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin LW, Rowe GA. Portal hypertension secondary to choledochal cyst. Ann Surg. 1979;190:638–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197911000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ando K, Miyano T, Kohno S, Takamizawa S, Lane G. Spontaneous perforation of choledochal cyst: A study of 13 cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8:23–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwasaki Y, Shimoda M, Furihata T, Rokkaku K, Sakuma A, Ichikawa K, et al. Biliary papillomatosis arising in a congenital choledochal cyst: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:1019–22. doi: 10.1007/s005950200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Fujii M, Toki A, Uemara S, Koike N, et al. Carcinoma arising from the bile duct in choledochal cyst and anomalous arrangement of the pancreatobiliary ductal union. Biliary Tract Pancreas. 1985;6:525–35. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu YB, Wang JW, Khagendra RD, Ji ZL, Li JT, Wang XA, et al. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults: Twenty-five- year experience. Chin Med J. 2007;120:1404–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang SP, Wang HP, Chen JH, Wu MS, Shun CT, Lin JT. Clinical application of EUS and peroral cholangioscopy in a choledochocele with choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:568–71. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lam WW, Lam TP, Saing H. MR cholangiography and CT cholangiography of pediatric patients with choledochal cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:401–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.2.10430145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matos C, Nicaise N, Deviere J, Cassart M, Metens T, Struyven J, et al. Choledochal cysts: Comparison of findings at MR cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in eight patients. Radiology. 1998;209:443–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.2.9807571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park DH, Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee SS, Choi JS, Lee YS, et al. Can MRCP replace the diagnostic role of ERCP for patients with choledochal cysts.? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cory DA, Don S, West KW. CT cholangiography of a choledochocele. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;21:73–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02010823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudhary A, Dhar P, Sachdev A. Reoperative surgery for choledochal cysts. Br J Surg. 1997;84:781–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Yanai T, Kobayashi H, Okazaki T, Lane GJ, et al. Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy or hepaticoduodenostomy for biliary reconstruction during the surgical treatment of choledochal cyst: Which is better? Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:5–7. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elhalaby E, Hashish A, Elbarbary M, Elwagih M. Roux -En-Y hepaticojejunostomy versus hepaticoduodenostmy for biliary reconstruction after excision of choledochal cysts in children. Ann Paediatr Surg. 2005;1:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liem NT, Dung le A, Son TN. Laparoscopic complete cyst excision and hepaticoduodenostomy for choledochal cyst: Early results in 74 Cases. J Laparoendosc Adv Tech A. 2009;19:S87–90. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0169.supp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei MF, Qi BQ, Xia GL, Yuan JY, Wang G, Weng YZ, et al. Use of the appendix to replace the choledochus. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:494–6. doi: 10.1007/s003830050381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tao KS, Lu YG, Wang T, Dou KF. Procedures for congenital choledochal cysts and curative effect analysis in adults. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis. 2002;1:442–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamataka A, Ohshiro K, Okada Y, Hosoda Y, Fujiwara T, Kohno S, et al. Complications after cyst excision with hepaticoenterostomy for choledochal cysts and their surgical management in children versus adults. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe Y, Toki A, Todani T. Bile duct cancer developed after cyst excision for choledochal cyst. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:207–21. doi: 10.1007/s005340050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma A, Pandey A, Rawat J, Ahmed I, Wakhlu A, Kureel SN. Conventional and unconventional surgical modalities for choledochal cyst: Long-term follow-up. Ann Pediatr Surg. 2011;7:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gander JW, Cowles RA, Gross ER, Reichstein AR, Chin A, Zitsman JL, et al. Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cysts with total intracorporeal reconstruction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:877–81. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Parthasarathi R, Amar VA, Senthilnathan PA. Laparoscopic management of choledochal cysts: Technique and outcomes-A retrospective study of 35 patients from a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:839–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohtsuka T, Inoue K, Ohuchida J, Nabae T, Takahata S, Niiyama H, et al. Carcinoma arising in choledochocele. Endoscopy. 2001;33:614–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hussain ZH, Bloom DA, Tolia V. Caroli's disease diagnosed in a child by MRCP. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:289–91. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(00)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Kerckhove L, De Meyer M, Verbaandert C, Mourad M, Sokal E, Goffette P, et al. The place of liver transplantation in caroli's disease and syndrome. Transpl Int. 2006;19:381–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]