Abstract

Background/Aim:

We investigated the effect of bone marrow-derived stem cell (BMSC) transplantation on carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis.

Patients and Methods:

BMSCs of green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice were transplanted into 4-week CCl4 -treated C57BL/6 mice directly to the liver, and the mice were treated for 4 more weeks with CCl4 (total, 8 weeks). After sacrificing the animals, quantitative data of percentage fibrosis area and the number of cells expressing albumin was obtained. One-way analysis of variance was applied to calculate the significance of the data.

Results:

GFP expressing cells clearly indicated migrated BMSCs with strong expression of albumin after 28 days post-transplantation shown by anti-albumin antibody. Double fluorescent immunohistochemistry showed reduced expression of αSMA on GFP-positive cells. Four weeks after BMSC transplantation, mice had significantly reduced liver fibrosis as compared with that of mice treated with CCl4 assessed by Sirius red staining.

Conclusion:

Mice with BMSC transplantation with continuous CCl4 injection had reduced liver fibrosis and a significantly improved expression of albumin compared with mice treated with CCl4 alone. These findings strengthen the concept of cellular therapy in liver fibrosis.

Keywords: Albumin, green fluorescent protein (GFP), liver fibrosis, mice, αSmooth Muscle Actin (α SMA)

Liver fibrosis is characterized as the repeated injury causing the remodeling of the liver tissue resulting in the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix with scar tissue encapsulating the area of injury.[1] This condition resulted in many clinical complications, such as ascites, variceal hemorrhage, and encephalopathy.[2] Different diseases, such as Wilson's disease, viral hepatitis B and C (HBV and HCV), liver cancer, and cirrhosis can affect the liver. Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) has been widely used to induce liver fibrosis in experimental animals. The mechanism involves the addition of one electron to CCl4 on binding to ferric cytochrome P450 and cleaving of the carbon–chloride bond. This binding results in a highly reactive trichloromethyl free radical and causes liver cell necrosis and destruction of the extracellular matrix through lipid peroxidation of membranes.[3–5]

The nonhematopoietic part of the bone marrow, referred to as bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), are of interest because of the simple isolation from a small aspirate of bone marrow.[6] BMSCs have shown a large in vitro and in vivo differentiation potential.[7] Their hepatic potential was first described by Lee et al.[8] Some recent studies also evidenced in vivo potential of BMSCs.[9] A key advantage of using BMSCs is their immunologic properties.[10] They were first shown to be engrafted in the recipient's liver and differentiated into hepatocytes by Petersen et al.[11] Therefore, BMSCs can be a useful source for cellular therapy in treating liver fibrosis.[12]

BMSCs could repair CCl4 -injured liver by reducing inflammation, collagen deposition, and remodeling.[13] Sakaida et al[14] found that BMSCs treatment to 4-week CCl4 -induced rats would result in significantly reduced liver fibrosis. A study by Oh et al[15] found that two of the liver-specific proteins alfa-feto protein and albumin were expressed in rat bone marrow cell culture. Some other studies also reported that BMSCs can express albumin in in vitro conditions.[16–18] In this present study, green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ BMSCs were transplanted into CCl4 -induced liver fibrotic mouse model. The co-expression of albumin in the GFP+ BMSCs was observed in CCl4 -induced liver after 2 and 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation. After 4 weeks, transplanted GFP+ BMSCs showed increased expression of albumin and a significant reduction in fibrosis was observed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Mice

GFP-transgenic mice and C57BL/6 wild-type mice were used in the experiment. All animals were treated according to procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board at the National Center of Excellence in Molecular Biology, Lahore, Pakistan. All animals were housed in conventional cages under controlled conditions of temperature (23°C ± 3°C) and relative humidity (50% ± 20%), with light illumination for 12 h/day.

BMSCs preparation

For BMSCs isolation, GFP-transgenic mice (6 weeks old) were killed and the limbs were removed. BMSCs were flushed with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) from the medullary cavities of tibias and femurs using a 25-G needle. Then cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplement with 20% FBS (Sigma, USA), 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin in a 25 cm2 culture flasks and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 . When cell confluency reached to 70–80%, they were detached with 0.25% Trypsin and 0.1% EDTA, and subcultured in two 25 cm2 flasks till second passage.

Experimental protocol

Six weeks old female C57BL/6 mice were treated with 1 ml/ kg CCl4 dissolved in olive oil (1:1) twice a week for 4 weeks intraperitoneally.[14] Animals were divided into 3 groups (n = 10 each); CCl4 control group, BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 2 weeks and BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 4 weeks. Twenty-four hours after the last injection of CCl4, 1 × 105 GFP+ BMSCs were injected directly into liver as described previously.[19] Same volume of saline water was injected in CCl4 control animals. After 2 and 4 weeks of post-transplantation, mice were sacrificed to assess the extent of liver fibrosis and expression of albumin. All mice were kept on receiving CCl4 during the post-transplantation period.

Histology of liver tissue

The liver was perfused via the heart with 4% paraformaldehyde to flush out blood cells and incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Tissues were then soaked in 30% sucrose for 3 h and frozen in liquid nitrogen to prepare for sectioning. Cells expressing albumin and αSMA were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using anti-albumin (1:50; Abcam, USA) and anti-αSMA antibodies (1:400; Sigma–Aldrich, Germany). Tissues were soaked in 0.3% Triton X-100 with 2% normal goat serum (Chemi-Con, Temecula, CA, USA). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. For fluorescent immunohistochemistry, we used fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-mouse as secondary antibody. For the evaluation of fibrosis, picro-sirius red staining was performed using 0.1% picro-sirius red solution as previously described. Fluorescence images were taken by Olympus BX61 microscope equipped with DP-70 camera (Olympus, Japan).

Quantitative analysis of liver fibrosis

We quantified the liver fibrosis area with picro-sirius red staining using an Olympus microscope equipped with a DP-70 camera (Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, the red area, considered the fibrotic area, was assessed by computer-assisted image analysis with Image J software (NIH). The mean value of 3 randomly selected areas per sample was used as the expressed percent area of fibrosis.

Gene expression analysis

RNA from liver tissue of all experimental groups was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using 1μg of total RNA by Revert Aid H Minus first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, Maryland, USA). Gene-specific primers were designed using online software Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). Sequences of the genes were taken from NCBI. All primer sequences are mentioned in Table 1 and following thermal conditions: 4 min at 94°C, followed by 31–35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 56–58°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s, then final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized and photographed after electrophoresis in 2% (w/v) agarose gels containing 0.5 mg/ mL ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data of percent fibrosis area and cells expressing albumin of 10 animals was obtained. Results are presented as the mean ± SD. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS

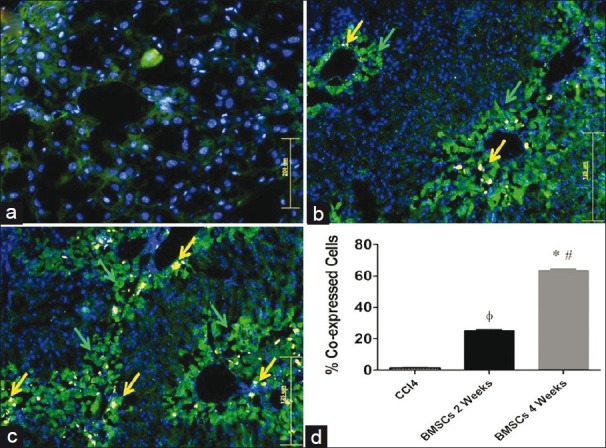

Mice chronically infected with CCl4 were treated with GFP+ BMSCs by injecting into the left lateral lobe of the liver. Bright GFP+ cells were engrafted and observed in all lobes of the liver, indicating cell migration from left lateral lobe to other injury sites as well [Figure 1b] as compared to non-transplanted mice [Figure 1a]. GFP+ cells in mice sacrificed after 2 weeks co-expressed albumin in the hepatic parenchyma [Figure 2b]. Later at 4th week, the transplanted sections expressed GFP+ cells with enhanced expression of albumin [Figure 2c]. GFP+ albumin expressing cells were not present in the fibrotic mouse liver transplanted with saline water [Figure 2a]. Statistical data [Figure 2d] showed that BMSCs transplanted liver showed significantly higher number of cells expressing albumin (60 cells/field) after 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation as compared with other groups (22 cells/field in BMSCs 2 weeks group).

Figure 1.

Homing of transplanted GFP+ BMSCs in CCl4 (a) and BMSCs (b) groups. DAPI was used to identify nuclei (magnification = 200×; n = 10 each)

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical expression of albumin in mouse liver. (a) CCl4 group, (b) BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 2 weeks, (c) BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 4 weeks (original magnification = 200×), (d) one-way analysis of variance was applied to check the significance of the data (n = 10). All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for BMSCs 4 weeks vs CCl4 control, #P < 0.05 for BMSCs 4 weeks vs BMSCs 2 weeks, ΦP < 0.05 for BMSCs 2 weeks vs CCl4 control

Fluorescence staining (anti-α smooth muscle actin with green color) indicated that a fine network pattern of stellate cells existed in the liver treated with CCl4 alone [Figure 3a]. Conversely, GFP+ BMSCs transplanted groups showed reduced expression of αSMA in fibrotic liver [Figure 3b and c]. Mice sacrificed after 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation showed significantly reduced expression of αSMA as compared with other groups [Figure 3c].

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical expression of αSMA in fibrotic mouse. (a) CCl4 group, (b) BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 2 weeks (c) BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 4 weeks. Considerable reduction in the expression of αSMA can be observed (original magnification = 200×)

After 4 weeks, the BMSCs transplanted liver clearly showed reduction of liver fibrosis compared to the group treated with CCl4 alone and BMSCs transplanted groups [Figure 4a–c]. Quantitative analysis [Figure 4d] of liver fibrosis by Image J software indicated that the percent fibrotic area of liver after 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation was significantly reduced to 1.17% ± 0.34% as compared to other groups (2.35% ± 0.66 = BMSCs 2 weeks group and 4.56% ± 1.75 = CCl4 group). The reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis showed reduction in the expression of αSMA and collagen 1α1 genes after 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation while the expression of these genes was increased after CCl4 injury. MMP-9 is known to be an antifibrotic marker released by BMSCs.[20] After BMSCs transplantation the expression of MMP-9 was noted to increase along with albumin, which is a hepatic functional marker [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of liver sections stained with sirius red. (a) CCl4 group, (b) BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 2 weeks, (c) BMSCs transplanted group sacrificed after 4 weeks (original magnification = 200×), (d) quantitative analysis of fibrosis in different experimental groups. One-way analysis of variance was applied to check the significance of the data (n = 10 each group). All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for BMSCs 4 weeks vs CCl4 control, #P < 0.05 for BMSCs 4 weeks vs BMSCs 2 weeks, ΦP < 0.05 for BMSCs 2 weeks vs CCl4 control

Figure 5.

RT-PCR analysis of fibrotic (αSMA, collagen 1α1), antifibrotic (MMP-9), and hepatic (albumin) genes following the BMSCs transplantation in CCl4-injured mouse liver after 2 and 4 weeks post-transplantation

DISCUSSION

In this study, CCl4 -induced liver fibrosis was ameliorated after transplantation of BMSCs. BMSCs could ameliorate liver fibrosis by expressing certain antifibrotic factors, such as MMP-9[18] and also by releasing some factors, such as soluble Kit-ligand related to the differentiation and proliferation of transplanted BMSCs in liver inflammation induced by continuous injection of CCl4 .[14] BMSCs secrete certain growth factors, such as hepatic growth factor (HGF), nerve growth factor (NGF), and many cytokines. These have antiapoptotic activity in hepatocytes and play an essential part in the regeneration of liver.[21,22]

MMP-9 was reported to have a role in the migration of BMSCs to the inflammatory site.[23] Transplanted BMSCs resulting in the degradation of the extracellular matrix may presumably lead to improved liver function and better survival of mice. According to our present data, increased expression of GFP+ cells at the site of liver injury contributed to the degradation of interstitial collagens, which has been shown by cirius red staining [Figure 4]. This collagen is degraded to gelatin, which was degraded by MMP-9 resulting in the regression of fibrosis.[24] Our study indicated an enhanced expression of MMP-9 [Figure 5] and reduced collagen deposition [Figure 4] after BMSCs transplantation.

The expression of αSMA, which is a marker of activated hepatic stellate cells, was reduced significantly after 4 weeks of GFP+ BMSCs transplantation [Figures 3 and 5]. Thus, transplanted BMSCs may affect activated stellate cells by inhibiting them or by leading them to apoptosis.[25] Collagen lαl, another fibrotic factor produced by activated hepatic stellate cells, was accumulated after CCl4 -induced fibrotic liver injury. Our results indicated a reduced. RNA expression of collagen IαI gene after 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation compared with the liver treated with CCl4 alone. These results are in line with those of Sakaida et al's.[14]

Fang et al.[13] reported that albumin-positive donor-derived cells were found at a lower frequency in CCl4 -injured liver tissue. Some other studies reported an increase in the serum albumin level.[26,27] In the current study, the expression of albumin was observed along with GFP+ BMSCs, indicating that albumin is expressed by the transplanted BMSCs [Figures 1 and 2]. RT-PCR analysis also showed a marked increase in the expression of albumin after 4 weeks of BMSCs transplantation [Figure 5].

The present study clearly indicates that BMSCs express albumin when transplanted to CCl4 -induced fibrotic liver. This study reveals that BMSCs ameliorate CCl4 -induced liver injury in mice by reducing fibrosis, expressing liver-specific genes, downregulating the expression of profibrotic genes, and upregulating antifibrotic and hepatic genes. In conclusion, the present study strengthens the concept of cellular therapy for the treatment of liver fibrosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues for the review of this manuscript. This work was supported by research grants from Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research grants from Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl 1):S38–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel Aziz MT, Atta HM, Mahfouz S, Fouad HH, Roshdy NK, Ahmed HH, et al. Therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on experimental liver fibrosis. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:893–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black D, Bird MA, Samson CM, Lyman S, Lange PA, Schrum LW, et al. Primary cirrhotic hepatocytes resist TGFbeta-induced apoptosis through a ROS-dependent mechanism. J Hepatol. 2004;40:942–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozdogan M, Ersoy E, Dundar K, Albayrak L, Devay S, Gundogdu H, et al. Beneficial effect of hyperbaric oxygenation on liver regeneration in cirrhosis. J Surg Res. 2005;129:260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim KH, Kim HC, Hwang MY, Oh HK, Lee TS, Chang YC, et al. The antifibrotic effect of TGF-beta1 siRNAs in murine model of liver cirrhosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:1072–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodbury D, Schwarz EJ, Prockop DJ, Black IB. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:364–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<364::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry FP, Murphy JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: Clinical applications and biological characterization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:568–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KD, Kuo TK, Whang-Peng J, Chung YF, Lin CT, Chou SH, et al. In vitro hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Hepatolology. 2004;40:1275–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.20469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aurich I, Mueller LP, Aurich H, Luetzkendorf J, Tisljar K, Dollinger MM, et al. Functional integration of hepatocytes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells into mouse livers. Gut. 2007;56:405–15. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.090050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niemeyer P, Kornacker M, Mehlhorn A, Seckinger A, Vohrer J, Schmal H, et al. Comparison of immunological properties of bone marrow stromal cells and adipose tissue-derived stem cells before and after osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:111–21. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen BE, Bowen WC, Patrene KD, Mars WM, Sullivan AK, Murase N, et al. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science J. 1999;284:1168–70. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohamadnejad M, Namiri M, Bagheri M, Hashemi SM, Ghanaati H, Zare Mehrjardi N, et al. Phase 1 human trial of autologous bone marrow-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J of Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3359–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i24.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang B, Shi M, Liao L, Yang S, Liu Y, Zhao RC. Systemic infusion of FLK1+ mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Transplantation. 2004;78:83–8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128326.95294.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaida I, Terai S, Yamamoto N, Aoyama K, Ishikawa T, Nishina H, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow cells reduces CCl4 -induced liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1304–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh SH, Miyazaki M, Kouchi H, Inoue Y, Sakaguchi M, Tsuji T, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces differentiation of adult rat bone marrow cells into a hepatocyte lineage in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:500–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang XQ, Zang WJ, Song TS, Xu XL, Yu XJ, Li DL, et al. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into hepatocytes in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3479–84. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong SH, Gang EJ, Jeong JA, Ahn C, Hwang SH, Yang IH, et al. In vitro differentiation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:1153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KD, Kuo TK, Whang-Peng J, Chung YF, Lin CT, Chou SH, et al. In vitro hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Hepatology. 2004;40:1275–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.20469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohsin S, Shams S, Ali Nasir G, Khan M, Javaid Awan S, Khan SN, et al. Enhanced hepatic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells after pretreatment with injured liver tissue. Differentiation. 2011;81:42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattori K, Heissig B, Wu Y, Dias S, Tejada R, Ferris B, et al. Placental growth factor reconstitutes hematopoiesis by recruiting VEGFR1 (+) stem cells from bone-marrow microenvironment. Nat Med. 2003;8:841–9. doi: 10.1038/nm740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Chen J, Chen XG, Wang L, Gautam SC, Xu YX, et al. Human marrow stromal cell therapy for stroke in rat: Neurotrophins and functional recovery. J Neurol. 2002;59:514–23. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuda-Hashii Y, Takai K, Ohta H, Fujisaki H, Tokimasa S, Osugi Y. Hepatocyte growth factor plays roles in the induction and autocrine maintenance of bone marrow stromal cell IL-11, SDF-1 alpha, and stem cell factor. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:955–61. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baram D, Vaday GG, Salamon P, Drucker I, Hershkoviz R, Mekori YA. Human mast cells release metalloproteinase-9 on contact with activated T cells: Juxtacrine regulation by TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2001;167:4008–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohuchi E, Imai K, Fujii Y, Sato H, Seiki M, Okada Y. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase digests interstitial collagens and other extracellular matrix macromolecules. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2446–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trim N, Morgan S, Evans M, Issa R, Fine D, Afford S, et al. Hepatic stellate cells express the low affinity nerve growth factor receptor p75 and undergo apoptosis in response to nerve growth factor stimulation. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1235–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64994-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, Zhao L, Xu Q, Zhang Y, Tang H. Differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocytes in hepatectomized mouse. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi. 2005;22:1234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oyagi S, Hirose M, Kojima M, Okuyama M, Kawase M, Nakamura T, et al. Therapeutic effect of transplanting HGF-treated bone marrow mesenchymal cells into CCl4-injured rats. J Hepatol. 2006;44:742–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]