Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation is a well-recognized complication that occurs in lymphoma patients who undergo chemotherapy. Only very few cases of HBV reactivation in patients with isolated antibody against hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) have been reported. We present a case of a 78-year-old woman diagnosed with diffuse large B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma who only displayed a positive anti-HBs, as the single possible marker of occult HBV infection, before starting therapy. She was treated with several chemotherapeutic regimens (including rituximab) for disease relapses during 3 years. Forty days after the last cycle of chemotherapy, she presented with jaundice, markedly elevated serum aminotransferase levels, and coagulopathy. HBV serology showed positivity for HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs. HBV DNA was positive. Antiviral treatment with entecavir was promptly initiated, but the patient died from liver failure. A review of the literature of HBV reactivation in patients with detectable anti-HBs levels is discussed.

Keywords: Anti-HBs positive, entecavir, hepatitis B virus, lymphoma, reactivation

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation is a well-known complication of patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy for hematologic malignancies.

HBV reactivation has been reported mostly in two different clinical scenarios. The first one refers to the vast majority of cases, and occurs in chronic carriers of HBsAg, in whom the diagnosis is based on elevation in serum transaminase levels associated with an increase on HBV-DNA viral load ≥ 1 log10 compared to baseline.[1] In the second scenario, HBV reactivation occurs in patients with occult HBV infection, that is, in patients who are HBsAg-negative, who have anti-HBc with or without anti-HBs, and who show detectable HBV-DNA in the liver with low level of serum HBV-DNA. Among these HBsAg-negative patients, HBV reactivation has been defined as a reappearance of HBsAg or the novo detection of HBV-DNA in the blood.[2,3]

Several risk factors of HBV reactivation have been identified, including male sex, young age, pre-existing liver disease, HBsAg positivity, lack of HBs antibodies, HBV-DNA level, presence of lymphoma, and use of anthracyclines or steroids or rituximab. Among these, in an exploratory analysis performed recently by Leo et al, male sex, lack of anti-HBs and use of rituximab were additional risk factors.[3]

HBV reactivation in patients with isolated anti-HBs is extremely rare and current guidelines do not offer a clear consensus regarding screening and management of these patients.[4–6]

We report a case of fatal HBV reactivation in an isolated anti-HBs positive patient, following chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Despite having initiated prompt treatment with entecavir, clinical condition worsened and the patient died from liver failure. We would like to underline that anti-HBs positivity can be the only marker of occult HBV infection and under these circumstances HBV reactivation can be fatal despite treatment with potent antiviral drugs.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old woman was diagnosed with localized diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; stage IB (modified Ann Arbor staging system), in September 2004. Her past medical history was relevant for beta thalassemia minor and blood transfusions in 2004. There was no history of liver disease, drug abuse, risk sexual activity, or contact with HBV-infected persons. There was no family history of HBV infection. Prior to the beginning of chemotherapy her liver enzymes were normal and virologic markers were negative for HBsAg and anti-HBc, and positive for anti-HBs (127 IU/mL). HBV-DNA level was not performed. There were no records on vaccination against HBV. After 8 cycles of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone, a complete remission was achieved in March 2005. In July 2008, a relapse was successfully treated with 8 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamicine, and prednisolone). Six months later, a second relapse was observed and successfully treated with 8 cycles of CHOP chemotherapy regimen. In June 2010 a third relapse, involving the central nervous system, was treated for 7 months, with 8 cycles of m-BACOD (bleomycin, adriamicine, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dexamethasone, methotrexate), resulting in complete remission. Prior to starting chemotherapy during these relapses HBV serology was not repeated. A PET scan was performed on February 4, 2011, and showed no evidence of the disease.

On February 22, 2011, 40 days after the completion of chemotherapy, she was admitted in the gastroenterology department with a 5-day history of jaundice, itching, and dark urine. No abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, night sweats, nausea, or vomiting were reported.

Physical examination was unremarkable except for icteric skin and sclera.

Laboratory data revealed an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 2804 IU/L (normal range (NR): 15–46), an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 2935 IU/L (NR: 13-69), an alkaline phosphatase (AP) of 224 IU/L (NR: 38–126), a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) of 277 IU/L (NR: 12–58), a total bilirubin of 367 μmol/L (NR: <22) with a direct fraction of 242 μmol/L (NR: <5 μmol/L), a prothrombin time of 18.8 s (NR: 11) and International Normalized Ratio of 1.66.

Viral serology markers showed HBsAg positive (4340 IU/mL), anti-HBs positive (106.3 IU/mL), anti-HBc positive (0.008 IU/mL), anti-HBc IgM positive (47.13 IU/mL), HBeAg negative and anti-HBe negative. HBV-DNA level, measured by real-time PCR, disclosed 2400 IU/mL. IgM anti-HAV, anti-EBV, anti-CMV, and anti-HSV1/2 were negative. Anti-HCV and HIV 1/2 were also negative. Auto-antibodies (ANA, ANCA, Anti-LKM, AMA, and ASMA) were negative. Liver ultrasonography showed no significant abnormalities.

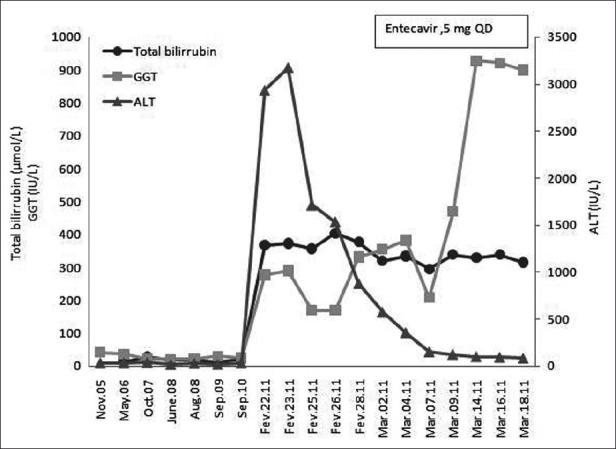

According to these findings the diagnosis of HBV reactivation was made. Antiviral therapy with entecavir at a dose of 0.5 mg orally per day was started on March 3, 2011. During the treatment a gradual decrease in ALT and AST levels was observed [Figure 1], but protrombin time did not significantly improve. Clinical deterioration was observed with the development of hepatic encephalopathy on March 19, 2011. The patient died on March 21, 2011, that is, 27 days after presentation, from liver failure. Due to this rapid and fatal outcome, HBV-DNA levels were not repeated.

Figure 1.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirrubin (TB), and gama-glutamyl transferase (GGT) before and during entecavir treatment, which was initiated at March 3, 2011

DISCUSSION

HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients is an under-recognized complication of immunosuppressive therapy. In two recent prospective studies, the incidence of HBV reactivation among HBsAg-negative lymphoma patients treated with a rituximab-containing regimen ranged from 4.1% to 11.8%.[7,8]

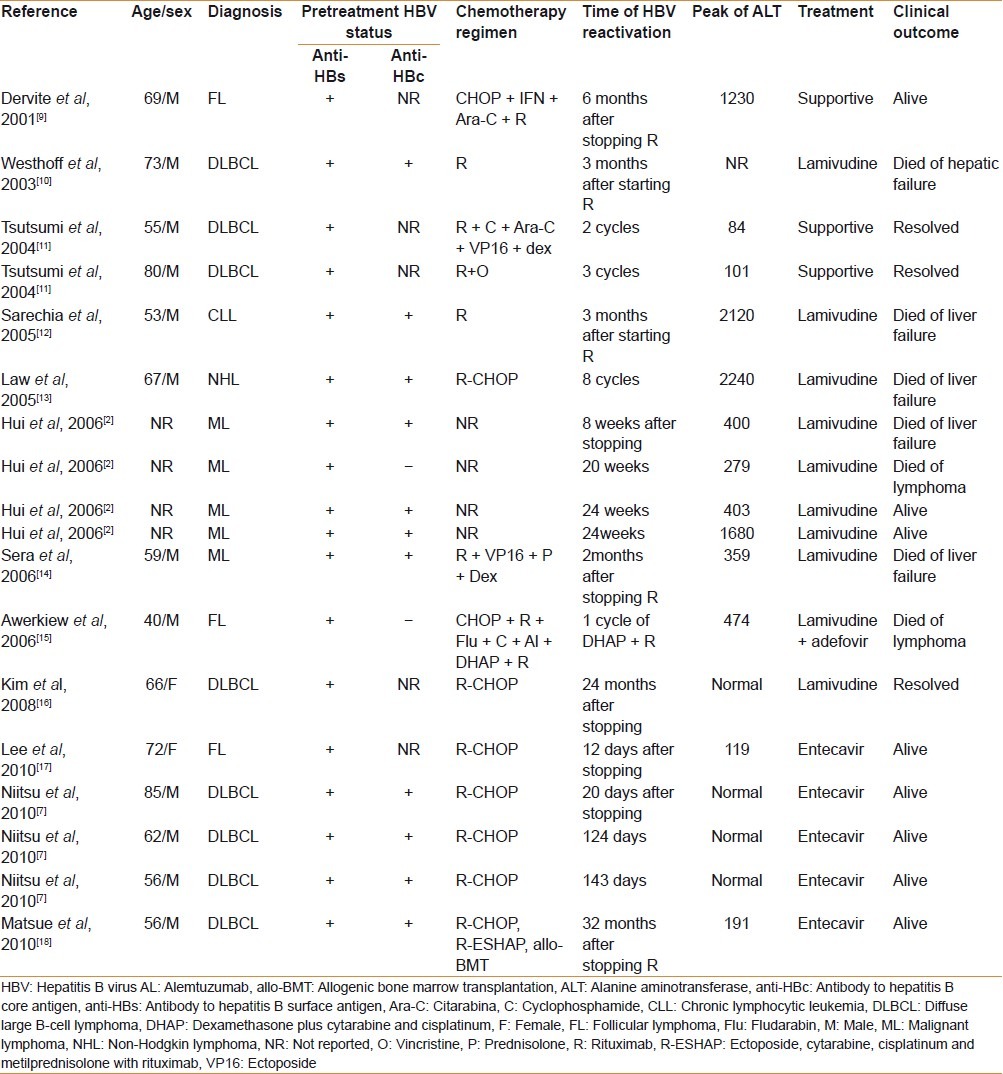

Although the presence of anti-HBs has been identified as a possible protective factor against HBV reactivation in patients with occult infection receiving chemotherapy,[3] few cases of HBV reactivation in anti-HBs positive lymphoma patients have been described in the literature, either as case reports[9–17] or in small series [Table 1].[2,7,18]

Table 1.

Reports of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs positive lymphoma patients

HBV reactivation in isolated anti-HBs positive lymphoma patients has been even more rarely reported. To the best of our knowledge, and as it is illustrated in Table 1, our case is the third case described in the literature and the first one with a fatal liver-related outcome. The reasons for the anti-HBc negativity in these patients remain unclear. It has been suggested that the production of antibodies may decline with age and so only anti-HBs persists.[19] On the other hand, anti-HBc–specific B cells may be deleted during previous immunosuppressive treatments.[15,16] As in our 78-year-old patient the first HBV markers were determined before any chemotherapy regimen was started, anti-HBc negativity is possibly due to a decline of immunocompetence related to age. Under these circumstances anti-HBs positivity may be actually the only marker for occult HBV infection.

Although de novo hepatitis B with non-neutralizing anti-HBs could explain the serological results observed in this patient, there are some aspects that make this hypothesis less likely. First, in patient's history there are no obvious percutaneous or sexual exposure to HBV or close person-to-person contact with HBV-infected persons that could lead to an acute transmission. Second, immunosuppression, which is so evident in this case, is a major risk factor for HBV reactivation not only in HBsAg-positive but also in HBsAg-negative patients. Third, HBV reactivation rather than de novo hepatitis B in isolated anti-HBs positive patients, although rarely, has been previously reported in the literature.

Rituximab plus steroid and rituximab combination chemotherapy have been recognized as risk factors for HBV reactivation among HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients.[2,3,8,20] In our patient HBV reactivation developed after 25 months of the last rituximab administration; however, a causal relationship with rituximab cannot be firmly established, because other chemotherapeutic agents that can promote HBV-reactivation were also used. Notwithstanding, as shown in Table 1, the most delayed case reported in the literature of HBV reactivation after stopping rituximab combination chemotherapy occurred at 32 months.[18]

There is no standard management to prevent HBV reactivation in unvaccinated patients with isolated anti-HBs positive. The consensus guidelines issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease recommend that patients who are HBsAg negative, anti-HBc positive and anti-HBs positive, or those with isolated anti-HBc should be monitored and antiviral therapy should be initiated when serum HBV-DNA becomes detectable.[4] Similar recommendations were made by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.[5] Patients with isolated anti-HBs, who are also at risk of HBV reactivation, are not contemplated in these evidence-based recommendations. The latest Japanese guidelines recommend that for patients who are positive for any HBV serological markers (HBsAg, Anti-HBc, or Anti-HBs), the presence of HBV-DNA should be confirmed by RT-PCR. If HBV-DNA is negative, HBV-DNA should be monitored monthly during and after chemotherapy for at least 1 year, and nucleoside analogs should be administered when HBV-DNA becomes positive.[6]

HBV reactivation should be treated initially with lamivudine or drugs with higher antiviral potency and lower long-term resistance rates.[4–6] Therefore, entecavir and tenofovir can be used as first-line therapy. In our case, although entecavir was immediately started, the patient died from liver failure. This was presumably due to the relative delay in the diagnosis of HBV reactivation that was only possible to make when severe acute hepatitis was already established.

In summary, this case illustrates that fatal HBV reactivation can occur in HBsAg-negative patients with isolated anti-HBs. Screening for HBV status for all patients prior to the use of rituximab-containing chemotherapy should therefore include anti-HBs determinations. Regular HBV-DNA monitoring should be considered in isolated anti-HBs positive patients and preemptive antiviral therapy should be administered when HBD-DNA becomes detectable.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:209–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, Au WY, Yueng YH, Leung AY, et al. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:59–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, Lam WY, Mo FK, Chu MT, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: Update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsubouchi H, Kumada H, Kiyosawa K, Mochida S, Sakaida I, Tanaka E. Prevention of immunosuppressive therapy or chemotherapy-induced reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection: Joint report of the Intractable liver diseases study group of Japan and the Japanese study group of the standard antiviral therapy for viral hepatitis. Kanzo. 2009;50:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niitsu N, Hagiwara Y, Tanae K, Kohri M, Takahashi N. Prospective analysis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma after rituximab combination chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5097–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima N, Mizuta T, Tanaka M, Yokoo M, Ide M, Hisatomi T, et al. Retrospective and prospective studies of hepatitis B virus reactivation in malignant lymphoma with occult HBV carrier. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:2013–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dervite I, Hober D, Morel P. Acute hepatitis B in a patient with antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen who was receiving rituximab. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:68–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westhoff TH, Jochimsen F, Schmittel A, Stoffler-Meilicke M, Schafer JH, Zidek W, et al. Fatal hepatitis B virus reactivation by an escape mutant following rituximab therapy. Blood. 2003;102:1930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsutsumi Y, Tanaka J, Kawamura T, Miura T, Kanamori H, Obara S, et al. Possible efficacy of lamivudine treatment to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation due to rituximab therapy in a patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:58–60. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0748-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarrecchia C, Cappelli A, Aiello P. HBV reactivation with fatal fulminating hepatitis during rituximab treatment in a subject negative for HBsAg and positive for HBsAb and HBcAb. J Infect Chemother. 2005;11:189–91. doi: 10.1007/s10156-005-0385-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law JK, Ho JK, Hoskins PJ, Erb SR, Steinbrecher UP, Yoshida EM. Fatal reactivation of hepatitis B post-chemotherapy for lymphoma in a hepatitis B surface antigen-negative, hepatitis B core antibody-positive patient: Potential implications for future prophylaxis recommendations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1085–9. doi: 10.1080/10428190500062932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sera T, Hiasa Y, Michitaka K, Konishi I, Matsuura K, Tokumoto Y, et al. Anti-HBs-positive liver failure due to hepatitis B virus reactivation induced by rituximab. Intern Med. 2006;45:721–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Awerkiew S, Daumer M, Reiser M, Wend UC, Pfister H, Kaiser R, et al. Reactivation of an occult hepatitis B virus escape mutant in an anti-HBs positive, anti-HBc negative lymphoma patient. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:83–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim EB, Kim DS, Park SJ, Park Y, Rho KH, Kim SJ. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a surface antigen-negative and antibody-positive patient after rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy. Cancer Res Treat. 2008;40:36–8. doi: 10.4143/crt.2008.40.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee IC, Huang YH, Chu CJ, Lee PC, Lin HC, Lee SD. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after 23 months of rituximab-based chemotherapy in an HBsAg-negative, anti-HBs-positive patient with follicular lymphoma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73:156–60. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(10)70031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsue K, Kimura S, Takanashi Y, Iwama K, Fujiwara H, Yamakura M, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after rituximab-containing treatment in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2010;116:4769–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsutsumi Y, Ogasawara R, Kamihara Y, Ito S, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka J, et al. Rituximab administration and reactivation of HBV. Hepat Res Treat. 2010;2010:182067. doi: 10.1155/2010/182067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pei SN, Chen CH, Lee CM, Wang MC, Ma MC, Hu TH, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following rituximab-based regimens: A serious complication in both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:255–62. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]