Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To compare the efficacy of letrozole and clomiphene citrate (CC) in patients of anovulatory polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) with infertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This prospective randomized clinical trial included 204 patients of PCOS. 98 patients (294 cycles) received 2.5–5 mg of letrozole; 106 patients (318 cycles) received 50–100 mg of CC (both orally from Days 3–7 of menstrual cycle). The treatment continued for three cycles in both the groups. Main outcome measures: ovulation rate, endometrial thickness, and pregnancy rate. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 13 software. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS:

The mean number of dominant follicles in letrozole groups and CC groups was 1.86±0.26 and 1.92±0.17, respectively (P=0.126). Number of ovulatory cycle in letrozole group was 196 (66.6%) versus 216 (67.9%) in CC group (P=0.712). The mean mid-cycle endometrial thickness was 9.1±0.3 mm in letrozole group and 6.3±1.1 in CC group, which was statistically significant (P=0.014). The mean Estradiol [E2] level in clomiphene citrate group was significantly higher in CC group (364.2±71.4 pg/mL) than letrozole group (248.2± 42.2 pg/mL). 43 patients from the letrozole group (43.8%) and 28 patients from the CC group (26.4%) became pregnant.

CONCLUSION:

Letrozole and CC have comparable ovulation rate. The effect of letrozole showed a better endometrial response and pregnancy rate compared with CC.

KEY WORDS: Clomiphene citrate, letrozole, PCOS, randomized trial

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility and is responsible for 70% of infertility cases due to anovulation.[1] Clomiphene citrate (CC) has been the most widely used drug for the treatment of infertility since its introduction into clinical practice in the 1960s. It is known that clomiphene citrate results in an ovulation rate of 60–85% but a conception rate of only about 20%.[2] CC has a long half-life (2 weeks), and this may have a negative effect on the cervical mucus and endometrium, leading to discrepancy between ovulation and conception rates.[3–5] There has been a search for a compound capable of inducing ovulation but devoid of the adverse antiestrogen effects of CC. Recent studies have suggested that Letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, does not possess the adverse antiestrogenic effects of clomiphene and is associated with higher pregnancy rates than CC treatment in patients with PCOS.[6,7] Though evidence from larger trials is still awaited, some encouragement may be taken from the success of preliminary results showing aromatase inhibitor Letrozole may be regarded as a possible replacement for CC for the first-time treatment of anovulatory infertility.[3,7–9] The aim of this present prospective randomized trial was to compare results of letrozole with CC in patients with PCOS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective randomized controlled trial was performed at a tertiary care hospital from January 2005 to January 2010. The necessary ethical approval was taken from Institutional Review Board to conduct this study. The patients were counseled, and informed consent was taken before randomization. The inclusion criteria included patients in the age group of 20–35 years having infertility for more than one year, body mass index (BMI) <28, and patients of anovulatory PCOS. The patients of PCOS were recruited in the presence of oligomenorrhea (i.e., interval between periods were ≥35 days) or amenorrhea (i.e., absence of vaginal bleeding for 6 months), hirsutism, enlarged ovaries with multiple follicles (≥10 measuring 2–8 mm in diameter) as per Rotterdam's criteria on transvaginal ultrasonography (USG), and/or elevated serum testosterone. Finally the diagnosis of PCOS was made on the basis of revised Rotterdam 2003 criteria.[10] Presence of two out of three criteria (oligo and/or anovulation, clinical biochemical sign of hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries) was recommended as a diagnostic of PCOS.

In all patients, a comprehensive infertility work-up was done. This included tubal patency test, pelvic ultrasonography, husband semen analysis, and serum hormone measurements (FSH, LH, prolactin, estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone) on the 2nd to 5th day of the cycle. Patients having abnormality in any of these tests, which may be responsible for reproductive failure, were excluded form the study. All patients underwent laparoscopy and patients who had other factors, found on laparoscopy, which may be responsible for infertility, were also excluded from the study. Sample size was calculated using pregnancy rate as a primary outcome measure. On basis of previous studies,[3] to achieve a statistically valid comparison of pregnancy rates in the two groups, with a type I error of 0.05 and a power of 80%, a sample size of at least 40 women in each arm was required.

Randomization of recruited women was carried out using online software (http://www.randomization.com) to generate a random number table. All patients were randomized to receive one of the two drugs to be given over the next 3 months. Randomization codes (A, B) were packed into sealed opaque envelopes by an individual not involved in enrollment, treatment and follow-up of subjects to ensure concealment of allocation. One resident had the responsibility for dispensing the trial drugs to the patient based on the unique randomization code. At the end of allocation, the resident provided us with a randomization list.

Patients in letrozole group received ovulation induction with letrozole with starting dose of 2.5 mg, increasing up to 5 mg daily. Patients in clomiphene citrate group received CC with starting dose of 50 mg, increasing up to 100 mg daily. In both the groups, treatments were administered from Day 3 to Day 7 (total of 5 days) of a spontaneous cycle or withdrawal bleeding after a 5-day course of 10 mg/day medroxyprogesterone acetate. Serial transvaginal ultrasound was performed in each cycle in both the groups from 12th to 16th day until a mature follicle of diameter 18 mm or more and trilaminar layer of endometrial pattern were seen. The number of follicles and endometrial thickness (ET) in each cycle in patients of both the groups were documented. Ultrasound in all patients was demonstrated by single observer (first author) to remove the inter-observer bias. Injection hCG 10,000 IU intramuscularly was given to the patients when a dominant follicle ≥18 mm and ET ≥6 mm were observed. Ovulation was confirmed by seeing follicle collapse on subsequent USG and elevated serum progesterone (≥25 nmol/L). Each woman was asked to have timed intercourse 24 h to 36 h after ovulatory dose of hCG. Women in both the groups without evidence of ovulation and with negative pregnancy tests were asked to follow the respective schedule of treatment in subsequent cycles. Duration of treatment in both the groups was 3 months. Chemical pregnancy was assessed by serum level of beta hCG measurement once the patient missed her period.

Documentation of at least one gestational sac in USG was confirmed as clinical pregnancy. The mean number of follicles, endometrial thickness, ovulatory cycle rate, conception rate, and pregnancy outcome were compared in both the groups. The sample was divided into two groups using random allocated software. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 13 software. Student's t-test, Chi-square and Fisher's exact testes were used when appropriate. Results were expressed as mean and standard errors of mean. The P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

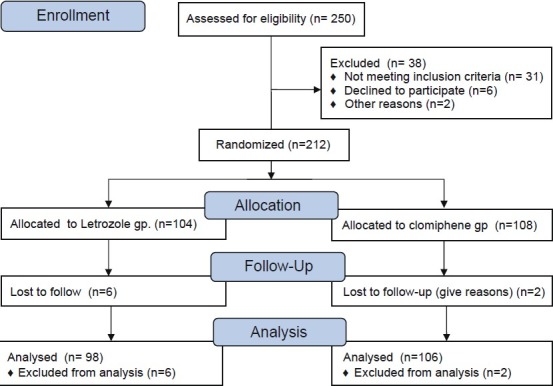

During the study period, a total of 250 patients were analyzed for recruitment. 38 patients did not meet inclusion criteria and eight patients were lost to follow-up in between the study, and therefore, 204 patients entered and completed the study. The flow of participants is shown in Figure 1. A total of 612 cycles of ovulation induction were carried out in 204 patients, out of which 294 cycles were in the letrozole group and 318 cycles were in the CC group. Of 106 patients in CC group, 69 patients had been given 50 mg clomiphene in all three study cycles, 18 patients were given 50 mg clomiphene in two cycles and stepped up to 100 mg in the third cycle, and 19 patients received 50 mg clomiphene in first cycle and 100 mg for second and third cycle. In the letrozole group, 72 patients received 2.5 mg letrozole in all three cycles, 14 patients received 2.5 mg for first two cycles and 5 mg in the third cycle, while 12 patients were stepped to 5 mg from the second cycle.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study

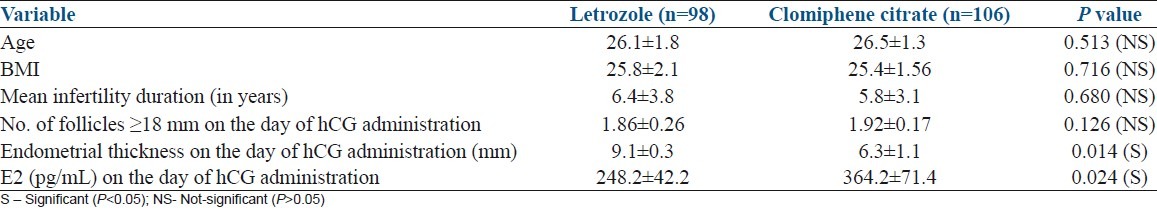

Table 1 summarizes the demographic profile of patients and the response of the women in the two groups to ovarian stimulation. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean age, BMI, and duration of infertility in both groups of patients.

Table 1.

Comparison of different variables in clomiphene citrate group and letrozole group based on mean±SD value

The mean number of dominant follicles (≥18 mm) in the letrozole and CC group was not statistically different (Letrozole 1.86±0.06 versus CC 1.92±0.17, P=0.126). The mean midcycle trilaminar layer of endometrial thickness in the letrozole group was 9.1±0.3 mm compared with 6.3±1.1 mm in CC group, which was statistically significant (P=0.014). We found no significant correlation with the number of dominant follicle and ET in both letrozole and CC groups. The mean total E2 on the day of hCG administration was significantly higher in CC group as compared with letrozole group (364.2±71.4 pg/mL versus 248± 42.2 pg/mL P=0.024).

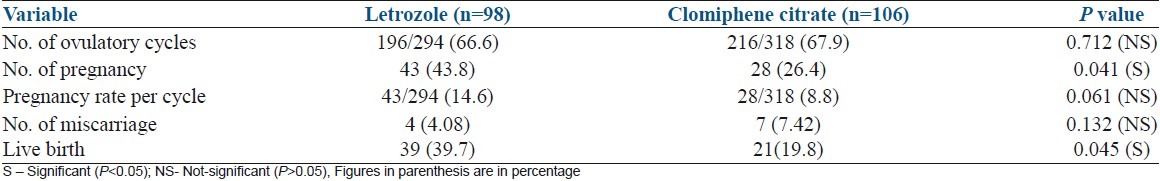

Table 2 shows number of ovulatory cycles, number of pregnancies, pregnancy rate/cycle and number of miscarriages and live births in each group. The ovulation rate in letrozole group and CC group was similar (84 of 98 patients (85.7%) [196 out of 294 cycles (66.6%)] in letrozole groups versus (92 of 106 patients (86.67%) [216 out of 318 cycles (67.9%)] in CC group. There was no occurrence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) in letrozole group compared with two cases of mild OHSS in CC group, which were managed conservatively. Out of 98 cases, 43 women became pregnant (43.8%) in letrozole group compared with 28 women who became pregnant out of 106 patients (26.4%) in CC group, which was statistically significant (P=0.041). Pregnancy rate (PR) per cycle was also higher in letrozole group (14.6%) in comparison with the CC group (8.8%), although this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.061). Two twin pregnancies and one triplet pregnancy occurred in the CC group and none in the letrozole group. The rate of spontaneous abortion in the first trimester was similar in both groups (4.08% in letrozole group versus 7.42% in CC group). There was significant difference between the two groups in terms of live birth rate (39 [39.7%] in the letrozole group versus 21 [19.8%] in the CC group P=0.045).

Table 2.

Comparison of ovulatory cycle, conception, and pregnancy outcome in clomiphene citrate group and letrozole group based on n (%)

DISCUSSION

For many years, CC has been used as the first treatment of choice for patients with PCOS. It is generally accepted that CC reduces uterine receptivity, and thus reduces the chances of conception.[11] It is associated with endometrial thinning in 15–50% of patients, probably due to estrogen receptor depletion.[12–14] Furthermore, the use of CC may block estrogen receptors in the cervix, producing a negative effect on the quality and quantity of cervical mucus.[4] Inappropriate development of the endometrium is associated with low implantation rate and early pregnancy loss due to luteal phase defect.[12,15] Aromatase inhibitors are non-steroidal compounds that suppress estrogen biosynthesis by blocking the action of the enzyme, aromatase, which converts androstenedione and testosterone to estrogens. Letrozole is a potent reversible oral aromatase inhibitor, which has been widely used in post-menopausal women with metastatic breast cancer.[16] It is given in a dose of 2.5–5 mg/day and has been shown to achieve optimal suppression of serum estrogen level and is almost free of side effects.[16–18] The efficient estrogen-lowering property of letrozole could be utilized to temporarily release the hypothalamus from negative feedback effect of estrogen and thereby inducing an increased discharge of FSH.[6] With letrozole, estrogen production is eventually advanced by the induced FSH discharge, but in contrast to the use of CC, the hypothalamus is able to respond to estrogen feedback with a negative feedback mechanism.[6,17] This helps in modulating an overzealous discharge of FSH, which in turn is more likely to result in a mono-follicular ovulation with moderate estrogen concentration. Letrozole also has an added positive effect, because peripherally, it may increase follicular sensitivity to FSH through amplification of FSH receptor gene expression.[19–22] Although letrozole creates an estrogen-deficient environment, it has no negative effect on the endometrium and cervix due to its short half-life (45 h).[23] In contrast, CC has a long half-life (2 weeks), and it is possible that CC concentrations could accumulate over subsequent cycles.[24] This could lead to increased risk of adverse endometrial or cervical mucus changes. Therefore, ovulation induction by letrozole is superior to CC in terms of follicular growth and endometrial response.[23,25] In contrast, one study[26] did not show any advantage to the use of letrozole over CC as a first-line treatment for induction of ovulation in women with PCOS. It is reported that using 2.5–5 mg/day of letrozole has a better endometrial response compared with endometrial response using CC in the dose of 50–100 mg/day.[15,25] This has also been reported that when letrozole is used in the dose of 7.5 mg and compared with 100 mg of CC, there was no significant difference in ET.[3] In contrast, another study reported that the endometrial development was higher in letrozole group using 7.5 mg of letrozole compared with that of 150 mg of CC.[23] Most commonly used doses in previous studies has been between 2.5 and 7.5 mg.[23,26] In our study, we used 2.5 mg daily of letrozole, increased to maximum 5 mg daily.

In the present study, though the mean number of dominant follicles (≥18 mm) was comparable in both the letrozole and CC group, the mean endometrial thickness was significantly better in letrozole group [(9.1±0.3 mm) compared with CC group (6.3±1.1 mm)]. Similar findings were reported in our previous study, which demonstrated that endometrial thickness and sub-endometrial blood flow were significantly better in cases receiving induction with letrozole than CC despite comparable follicular response.[25] Al-Fozan et al. also reported similar result in a randomized control trial of letrozole versus CC in women undergoing superovulation.[3] Similar to our previous study,[25] there was no positive correlation between ET and number of dominant follicles in both the group in the present study. It has been reported that serum E2 level on the day of hCG administration was statistically significantly lower in the letrozole group than the CC group.[26,27] In our study, we have also found that the mean total E2 on the day of hCG administration was significantly higher in CC group as compared with letrozole group. Unlike CC, which blocks and depletes estrogen receptors, letrozole has no effect on estrogen receptors. This explains a significantly higher ET on the day of hCG administration with letrozole compared with CC. hCG was routinely administered to these women to allow follicle maturation and exactly time the intercourse for these couples, to increase the favorable outcome. It has been proved that routine documentation of follicle monitoring, individualization of hCG dose, and documentation of ovulation has been especially beneficial in PCOS patients.[27]

With CC, supraphysiologic levels of estrogen can occur without control suppression of FSH because the normal estrogen receptor-mediated feedback mechanisms are blocked. This results in multiple follicular growth and higher multiple pregnancy rates with CC than are found in letrozole cycles.[28] Rashida Begam et al. reported higher ovulation rate (62.5%) with letrozole compared with 37.50% with CC.[23] Mitwally and Casper[6] using 2.5 mg/day of letrozole achieved 75% and 100% ovulation in anovulatory and ovulatory patients respectively. Higher ovulation rate with letrozole was also reported in other studies.[29,30] Ovulation rate was found to be similar reported by Bayer et al.,[26] (81% in letrozole group versus 85% in CC group). In the present study, we found comparable ovulatory rates (66.6% in letrozole group and 67.9% in CC group).

Though number of pregnancies in the present study is significantly higher in letrozole group (43.8%) compared with CC group (26.4%), there was no significant difference in pregnancy rate per cycle. This may be due to the fact that pregnancy depends on multiple factors in a particular cycle and therefore may not reflect the difference. Similar result was reported with use of 7.5 mg/day of letrozole and 150 mg/day of CC in patients of PCOS who failed to ovulate with 100 mg of CC in previous cycle.[23] Letrozole producing mono-follicular development reduces the chances of multiple pregnancies compared with CC. Mitwally et al.[30] reported low multiple gestation rates with aromatase inhibitors for ovulation induction. In our study, there was no multiple gestation in letrozole group compared with three multiple pregnancies in CC group.

Efficacy of letrozole in inducing ovulation with successful outcomes has been studied even in assisted reproduction for intrauterine insemination (IUI) and in vitro fertilization techniques.[31] Besides ovulation induction in anovulatory infertility, extended letrozole regimen had a superior efficacy as compared with clomiphene citrate in patients of unexplained infertility undergoing superovulation and IUI.[32] Letrozole has even been compared with recombinant FSH in inducing ovulation in women with PCOS and has been found to be a suitable and cost-effective inducing agent.[33]

Similar to previous studies,[26,28] there was no difference in the number of miscarriage in two groups in our study. Favorable pregnancy outcome with letrozole was reported by various studies.[28,30] A multicentric retrospective study in Canada by Tulandi et al.[34] on pregnancy outcome after letrozole induction of ovulation concluded that the concern about letrozole use for ovulation induction was unproven. In the present study, we found the live birth rate was significantly better in letrozole group compared with CC group, and there was no congenital malformation in either group.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our results of randomized trial suggest that letrozole is as good as CC in terms of ovulation rate. The endometrial thickness was significantly better in the letrozole group. Letrozole was also found to be superior in terms of number of pregnancy than CC. Therefore, letrozole is a safe and better alternative to CC in ovulation induction protocol for patients of anovulatory PCOS, and it may be considered as a first-line treatment for ovulation induction in these patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fleming R, Hopkinson ZE, Wallace AM, Greer IA, Sattar N. Ovarian function and metabolic factors in women with oligomenorrhea treated with metformin in a randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:569–74. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher SA, Reid RL, Van Vugt DA, Casper RF. A Randomized double-blind comparison of the effects of clomiphene citrate and the aromatase inhibitor letrozole on ovulatory function in normal women. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:280–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Fozan H, Al-Khadouri M, Tan SL, Tulandi T. A randomized trial of letrozole versus clomiphene citrate in women undergoing superovulation. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1561–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randall JM, Templeton A. Cervical mucus score and in vitro sperm mucus interaction in spontaneous and clomiphene citrate cycles. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:465–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura Y, Ono M, Yoshida Y, Sugino N, Ueda K, Kato H. Effects of clomiphene citrate on the endometrial thickness and echogenic pattern of the endometrium. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:256–60. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Use of an aromatase inhibitor of ovulation in patients with an inadequate response to clomiphene citrate. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:305–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atay V, Cam C, Muhcu M, Cam M, Karateke A. Comparison of letrozole and clomiphene citrate in women with polycystic ovaries undergoing ovarian stimulation. J Int Med Res. 2006;34:73–6. doi: 10.1177/147323000603400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nandi N, Bhattacharya M, Tolasaria A, Bhadra B. Experience of using letrozole as a first-line ovulation induction agent in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Al Ameen J Med Sci. 2011;4:75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polyzos NP, Tsappi M, Mauri D, Atay V, Cortinovis I, Casazza G. Aromatase inhibitors for infertility in polycystic ovary syndrome. The beginning or the end of a new era? Fertil Steril. 2008;89:278–80. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouta E, White DM, Franks S. Modern use of clomiphene citrate in induction of ovulation. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:359–65. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonen Y, Casoer RF. Sonographic determination of an adverse effect of clomiphene citrate on endometrial growth. Hum Reprod. 1990;5:670–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagel S, Ben-Chetrit A, Anteby E, Zacut D, Hochner-Celnikier D, Ron M. The effect of ethinyl estradiol on endometrial thickness and uterine volume during ovulation induction by clomiphene citrate. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:33–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickey RP, Olar TT, Taylor SN, Curole DN, Matulich EM. Relationaship of endometrial thickness and pattern of fecundity in ovulation induction cycles: Effect of clomiphene citrate alone and with menopausal gonadotropin. Fertile Steril. 1993;59:756–60. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55855-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickey RP, Holtkamp DE. Development, pharmacology and clinical experience with clomiphene citrate. Hum Reprod Update. 1996;2:248–506. doi: 10.1093/humupd/2.6.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamb HM, Adkins JC. Letrozole: A review of its use in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer. Drugs. 1998;56:1125–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856060-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homburg R. Clomiphene citrate – end of an era? A mini-review. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2043–51. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowsett M, Jones A, Johnston SR, Jacobs S, Trunet P, Smith IE. in vivo measurement of aromatase inhibitor by letrozole in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weil SJ, Vendola K, Zhou J, Adesanya OO, Wang J, Okafor J, et al. A androgen receptor controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in the primate ovary: cellular localization, regulation, and functional correlation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2479–85. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weil SJ, Vendola K, Zhou J, Bondy CA. Androgen and follicle-stimulating hormone interactions in primate ovarian follicle development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2951–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vendola K, Zhou J, Wang J, Famuyiwa OA, Bienre M, Bondy CA. Androgens promote oocyte insulin-like growth factor I expression and initiation of follicle development in the primate ovary. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:353–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vendola KA, Zhou J, Adesanya OO, Bondy CA. Androgen stimulate early stages of follicular growth in the primate ovary. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2622–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begum MR, Ferdous J, Begum A, Quadir E. Comparison of efficacy of aromatase inhibitor and clomiphene citrate in induction of ovulation in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:853–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young SL, Opsahl MS, Fritz MA. Serum concentrations of eclomiphene and zuclomiphene across consecutive cycles of clomiphene citrate therapy in anovulatory infertile women. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:639–44. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baruah J, Roy KK, Rahman SM, Kumar S, Sharma JB, Karmakar D. Endometrial effects of letrozole and clomiphene citrate in women with polycystic ovary syndrome using spiral artery Doppler. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:311–4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0714-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badawy A, Abdel Aal AI, Abulatta M. Clomiphene citrate or letrozole for ovulation induction in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: A prospective randomized trial. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:849–52. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Awwad JT, Farra CG, Awwad ST, Bu-Habib RM, Abdallah MA, Usta IM. The conventional doses of human chorionic gonadotropins may not always be sufficient to induce ovulation in all women: A reappraisal. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2001;28:240–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayar U, Tanriverdi AH, Barut A, Ayoglu F, Ozcan O, Kaya E. Letrozole vs. Clomiphene citrate in patients with ovulatory infertility. Fertil steril. 2006;85:1045–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Aromatase inhibitor improves ovarian response to follicle-stimulating hormone in poor responders. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:776–80. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitwally M, Biljan M, Casper R. Pregnancy outcome after the use of an aromatase inhibitor for ovarian stimulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:381–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Requena A, Herrero J, Landeras J, Navarro E, Neyro JL, Salvador C, et al. Use of letrozole in assisted reproduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:571–82. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fouda UM, Sayed AM. Extended letrozole regimen versus clomiphene citrate for superovulation in patients with unexplained infertility undergoing intrauterine insemination: A randomized controlled trial. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganesh A, Goswami SK, Chattopadhyay R, Chaudhury K, Chakravarty B. Comparison of letrozole with continuous gonadotropins and clomiphene-gonadotropin combination for ovulation induction in 1387 PCOS women after clomiphene citrate failure: A randomized prospective clinical trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulandi T, Martin J, Al-Fadhi R, Kabli N, Forman R, Hitkari J, et al. Congenital malformation among 911 newborns conceived after infertility treatment with letrozole or clomiphene citrate. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1761–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]