Abstract

Purpose

To analyze dosimetric variables and outcomes after adaptive replanning of radiotherapy during concurrent high-dose protons and chemotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods and Materials

Nine of 44 patients with stage III NSCLC in a prospective phase II trial of concurrent paclitaxel/carboplatin with proton radiation [74 Gy(RBE) in 37 fractions] had modifications to their original treatment plans after re-evaluation revealed changes that would compromise coverage of the target volume or violate dose constraints; plans for the other 35 patients were not changed. We compared patients with adaptive plans with those with nonadaptive plans in terms of dosimetry and outcomes.

Results

At a median follow-up of 21.2 months (median overall survival, 29.6 months), no differences were found in local, regional, or distant failure or overall survival between groups. Adaptive planning was used more often for large tumors that shrank to a greater extent (median, 107.1 cm3 adaptive and 86.4 cm3 non-adaptive; median changes in volume, 25.3% adaptive and 1.2% non-adaptive; p<0.01). The median number of fractions delivered using adaptive planning was 13 (range, 4–22). Adaptive planning generally improved sparing of the esophagus (median absolute decrease in V70, 1.8%; range, 0–22.9%) and spinal cord (median absolute change in maximum dose, 3.7 Gy; range, 0–13.8 Gy). Without adaptive replanning, target coverage would have been compromised in 2 cases (57% and 82% coverage without adaptation vs. 100% for both with adaptation); neither patient experienced local failure. Radiation-related grade 3 toxicity rates were similar between groups.

Conclusions

Adaptive planning can reduce normal tissue doses and prevent target misses, particularly for patients with large tumors that shrink substantially during therapy. Adaptive plans seem to have acceptable toxicity and achieve similar local, regional, and distant control and overall survival, even in patients with larger tumors, versus non-adaptive plans.

Keywords: proton radiation, adaptive planning, non-small cell lung cancer, image-guided radiation therapy, chemoradiation

INTRODUCTION

Several technological advances have the potential to improve the toxicity and outcomes of radiation therapy for lung cancer. Conformal techniques such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (1) and proton therapy (2–5) allow dose escalation while minimizing doses to normal tissues, which may decrease radiation-induced toxicity. Moreover, advances in treatment planning with 4-dimensional computed tomography (4D CT) have resulted in the ability to accurately target moving thoracic tumors (6). Image-guided radiotherapy has also provided the ability to accurately and reproducibly position targets on a daily basis (7). These advances have opened the door to the concept of adapting radiation therapy during the course of treatment to maximize target coverage and minimize the dose to normal tissues (8). As this relatively new concept develops and is integrated into practice, questions about how adaptive replanning may affect clinical outcomes, such as local control and toxicity, need to be addressed.

The dose distributions of proton beams are sensitive to changes in density in the lungs (9–11), and doses to critical structures such as the spinal cord and esophagus may exceed tolerances without proper planning and replanning during treatment (12). Furthermore, coverage of the internal clinical target volume (iCTV) may be compromised by changes in tumor shape, volume, or density over the course of the treatment. In this context, adaptive replanning refers to changing a treatment plan over the course of radiotherapy for the specific purpose of maintaining coverage of the iCTV at more than 95%, reducing the dose to normal tissues, or both. We recently published a phase II trial of concurrent paclitaxel/carboplatin and proton therapy for 44 patients with unresectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in which adaptive replanning was used in some cases (2).

In the present study, we reviewed these 44 cases to analyze the methods and rationale for using or not using adaptive replanning and comparing treatment outcomes (local control, regional control, distant control, overall survival, and toxiticity) between patients who had adaptive plans and patients who had non-adaptive plans. Furthermore, we sought to determine possible dosimetric advantages of adaptive plans over dosimetry that would have been delivered had non-adaptive planning been used instead, accounting for changes during treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and treatment

Patients had histologically or cytologically confirmed stage III NSCLC (2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system) and were enrolled in a prospective phase II study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00495170) of concurrent paclitaxel/carboplatin and proton radiation therapy (2). Chemotherapy (paclitaxel, 50 mg/m2, and carboplatin, 2 area-under-the-curve units) was given weekly during radiotherapy. Radiation to the tumor was administered once daily for 5 days per week at 2 Gy(RBE) per fraction to a total dose of 74 Gy(RBE). Passive scattering proton therapy was used. Treatment planning simulation was done in all cases with 4D CT scanning, and planning was performed as previously described (2, 3, 13–15).

Adaptive planning

All 44 patients in the phase II study underwent replanning evaluation, in most cases (34) with 4D CT (the other 10 had small tumors away from critical structures and were evaluated clinically and with daily kilovoltage imaging). The replanning evaluation process started with a 4D CT resimulation, typically at week 3 or 4 of treatment, to assess tumor response. In those evaluations, the internal gross tumor volume (iGTV) (7) and internal clinical target volume (iCTV, defined as iGTV plus 8 mm margin with clinical edits) were re-contoured, and a “confirmation” plan was created by applying the original plan to the resimulation scan. If the confirmation plan demonstrated either coverage of <95% of the iCTV or excessive normal tissue doses (exceeding those in Supplemental Table 1), then an adaptive plan was created for the remainder of the 7-week treatment period. Adaptive plans were created for 9 patients (20%) on the basis of these evaluations. This adaptive planning could entail changes in apertures, compensators, beam angles, beam energies, beam ranges, or numbers of beams, any of which could be manipulated independently, as described elsewhere (12).

To estimate the dosimetric effects of these adaptive changes, we generated 2 sets of composite proton radiation plans for the patients who had adaptive planning; the first composite plan comprised (1) the original plan on the original 4D CT and (2) the original plan on the resimulation 4D CT (the confirmation plan). The second composite plan comprised (1) the original plan on the original 4D CT and (2) the new plan on the resimulation scan (the adaptive plan). The iCTV coverage and normal tissue dose-volume histograms (DVHs) of these composite plans were compared with specific attention to the spinal cord maximum dose; esophagus volume receiving 60 Gy(RBE) (V60) or 70 Gy(RBE) (V70); mean lung dose (MLD), lung V5, V10, and V20; and heart V40.

Patient evaluation and follow-up

Patients were monitored and evaluated as previously described (2). Evaluations took place at least weekly during treatment, at 6 weeks after completion of therapy, and then every 3 months for 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3. Serial thoracic CT scans with contrast were used to evaluate local control, and if those scans suggested recurrent disease, then a positron emission tomography (PET) scan was required and biopsy recommended. Unconfirmed recurrent disease was followed up with CT or PET scans. The date of recurrence was scored as the time at which the first abnormality was detected, and the interval calculated relative to the date of protocol enrollment. Survival was calculated as the time from enrollment to the last follow-up or the documented date of death.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival, local control, regional control, and distant control were calculated from Kaplan-Meier curves. Curves for patients with adaptive plans were compared with those for patients with non-adaptive plans by using log-rank tests. SPSS v16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to analyze differences in survival, with p < 0.05 considered significant. Analysis of variance was used to compare characteristics between groups.

RESULTS

Patient and disease characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics

| Patient Characteristics (n=44) | Patients with Adaptive Plans (n=9) | Patients with Non-adaptive Plans (n=35) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 7 (78%) | 24 (69%) |

| Female | 2 (22%) | 11 (31%) |

| Age, n (%) | ||

| ≤70 years | 5 (56%) | 21 (60%) |

| >70 years | 4 (44%) | 14 (40%) |

| Tumor stage, n (%) | ||

| IIIA | 2 (22%) | 19 (54%) |

| IIIB | 7 (78%) | 16 (46%) |

| Cancer histology, n (%) | ||

| Squamous cell | 4 (44%) | 21 (59%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 (56%) | 10 (29%) |

| Non-small cell, NOS | 0 | 4 (12%) |

| Internal gross tumor volume, cm3 median (range) | ||

| Before chemoradiation | 107.1 (70.1–430.7) | 86.4 (4.1–753.2) |

| At re-simulation | 91.9 (44.2–305.3) | 83.6 (4.1–678.9) |

| Percent change | 25.3% (1.4–58.7%) | 1.2% (0–45.8%) |

| Karnofsky performance status score, median (range) | 90 (70–100) | 90 (70–100) |

| Vital status at time of analysis | ||

| Alive | 5 (56%) | 17 (49%) |

| Dead | 4 (44%) | 18 (51%) |

| Follow-up time, months median (range) | 22.6 (8.1–47.1) | 19.2 (6.1–43.0) |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | ||

| Neoadjuvant | 3 (30%) | 8 (24%) |

| Weekly | 9 (100%) | 35 (100%) |

| Adjuvant | 1 (10%) | 7 (21%) |

Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified.

Nine patients had adaptive planning; another 2 patients had multiple plans, but their plans were not adaptive and were designed at the original simulation as part of initial plans. Patients who received adaptive plans tended to have more advanced disease and larger tumors, with greater decreases in tumor volume (median 25.3%) than patients who had non-adaptive plans (median 1.2%; p < 0.01; Table 1). Most patients were men younger than 70 years with good performance status (median Karnofsky performance scale score, 90; range, 70–100). The median follow-up time for all patients was 21.2 months.

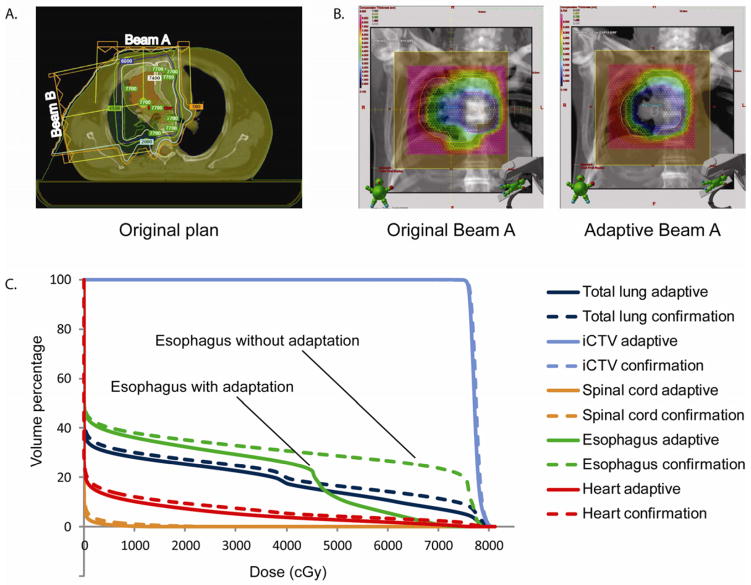

Adaptive planning characteristics

An example of an adaptive plan is shown in Figure 1. The substantial reduction in tumor volume in this patient led to a markedly different dose distribution at the replanning evaluation, after about half of the total radiation had been delivered. The original beam arrangements are shown in Figure 1a. The colors in Figure 1b represent the various thicknesses of the compensator, which overlays the bronze aperture. The DVH data for an adaptive plan and for a non-adaptive plan are shown in Figure 1c. The adaptive plan was created by changing the compensators for each aperture and calculating new beam energies and ranges.

Figure 1.

Example of adaptive planning. (a) The original beam arrangements. (b) The compensators are superimposed on the bronze apertures for the original and adaptive plans, with the different colors representing different compensator thicknesses. (c) Dose-volume histogram reveals notable differences in coverage, particularly for the esophagus.

The median number of adaptive fractions delivered was 13 (range, 4–22); for the 34 patients who had 4D CT re-evaluation, the median time at which this took place was at treatment week 4 (range, 2–4.7 weeks). Of the 9 patients who received adaptive replanning, 8 were re-evaluated during week 3 or 4 of treatment; the ninth patient, whose re-evaluation took place during week 2 of treatment, had a 58% reduction in the iGTV by that time. The beam energy was changed in the adaptive plans for 5 patients and the beam range in the adaptive plans for 73patients. The compensator was changed in the adaptive plans for 8 patients and the aperture in the adaptive plans for 4 patients. By contrast, the number of beams was3changed less often, in only 2 patients (Table 2). 3

Table 2.

Adaptive methods used and the resulting dose-volume histogram changes

| Plan Type | Patient No. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Characteristics | ||||||||||

| No of adaptive fractions delivered | 7 | 13 | 4 | 10 | 13 | 22 | 12 | 15 | 13 | |

| Adaptive methods used | Ap, Comp, En, Rg | Bm. no. | Comp, En, Rg | Comp, Bm ang, Rg | Comp, Bm no. | Ap, Comp, En, Rg | Ap, Comp, En, Rg | Ap, Comp, En, Rg | Comp, Rg | |

| iCTV coverage | C | 95 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 94 | 97 | 82 | 100 | 57 |

| A | 95 | 97 | 100 | 97 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Heart V40 (%) | C | 13.1 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 11.2 |

| A | 13.3 | 12.1 | 14.0 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 22.7 | |

| Lung V5 (%) | C | 51.4 | 30.0 | 32.9 | 37.8 | 20.7 | 43.5 | 29.0 | 32.2 | 58.5 |

| A | 51.1 | 34.5 | 33.1 | 32.8 | 21.2 | 41.1 | 28.4 | 30.2 | 43.1 | |

| Lung V10 (%) | C | 44.4 | 26.3 | 30.7 | 33.4 | 17.9 | 39.8 | 27.7 | 30.1 | 52.0 |

| A | 43.7 | 25.0 | 31.1 | 29.7 | 18.5 | 37.0 | 27.0 | 28.2 | 39.4 | |

| Lung V20 (%) | C | 28.9 | 23.2 | 27.0 | 29.0 | 13.1 | 34.4 | 25.7 | 27.3 | 39.5 |

| A | 28.2 | 22.5 | 27.0 | 25.0 | 14.5 | 31.5 | 24.8 | 25.4 | 35.1 | |

| Lung mean dose (Gy) | C | 19.1 | 19.1 | 15.5 | 19.6 | 7.8 | 18.2 | 15.0 | 16.5 | 22.7 |

| A | 18.4 | 14.1 | 17.1 | 17.0 | 7.6 | 16.3 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 19.7 | |

| Esophagus V60 (%) | C | 49.5 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 40.8 | 0.5 | 34.8 | 3.9 | 26.7 | 37.8 |

| A | 47.5 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 33.7 | 1.4 | 22.7 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 46.5 | |

| Esophagus V70 (%) | C | 41.5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 0.2 | 23.8 | 19.8 |

| A | 39.7 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 42.8 | |

| Esophagus mean dose (Gy) | C | 43.2 | 13.9 | 5.0 | 41.0 | 15.3 | 30.4 | 20.8 | 24.1 | 35.3 |

| A | 42.6 | 12.9 | 5.5 | 35.8 | 17.5 | 24.8 | 20.1 | 16.4 | 38.4 | |

| Spinal cord max dose (Gy) | C | 45.2 | 23.6 | 37.1 | 47.9 | 40.6 | 23.2 | 57.8 | 28.8 | 39.0 |

| A | 41.5 | 18.3 | 40.4 | 41.2 | 40.6 | 22.2 | 45.0 | 15.0 | 35.3 | |

Abbreviations: Ap, aperture; Comp, compensator; En, energy; Rg, range; Bm no., number of beams; Bm ang, beam angle; C = confirmation plan; A = adaptive plan; Vx = percentage of organ volume receiving at least x Gy; iCTV = internal clinical tumor volume.

Outcomes

The median overall survival for all 44 patients was 29.6 months. At 2 years, the local control rate for all patients was 79.5% and the overall survival rate was 57.4% (2). No significant differences were found between groups in local control (7 failures among 35 patients who had non-adaptive plans and 2 of 9 patients who had adaptive plans), regional control (4 failures in the nonadaptive group and none in the adaptive group), distant control (15 failures in the non-adaptive group and 4 in the adaptive group), or overall survival (18 deaths in the non-adaptive group and 4 in the adaptive group) (p>0.05 for all) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Outcomes after concurrent high-dose proton therapy and chemotherapy for patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer depending on whether the patient did or did not receive adaptive replanning. Although the numbers of patients were small (9 received adaptive plans and 35 non-adaptive plans), log-rank tests revealed no differences in local control (a), regional control (b), distant control (c), or overall survival (d) between the groups.

Effects of adaptive planning on normal tissue dose-volume relationships

All 9 patients who had adaptive plans also had composite plans that could be used to compare the overall effect of the adaptive plan with that of the original plan after resimulation (the confirmation plan) (Table 2). Differences in dosimetric variables between the two plans were usually small for the heart V40 and the lung MLD and V20. However, larger differences were evident for the esophagus V70 (median absolute reduction 1.8%; range, 0–22.9%) and the spinal cord maximum dose [median absolute change 3.7 Gy(RBE); range, 0–13.8 Gy(RBE)]. Patients who had 4D CT resimulation to evaluate response during treatment but did not have adaptive planning showed minimal to no differences between the original and the re-evaluation plans and thus did not warrant adaptive replanning (data not shown).

Effect of adaptive planning on tumor coverage

For 2 of the 9 adaptive plans, the iCTV coverage would have been compromised had the plans not been adapted: iCTV coverage would have decreased to 82% for patient 7 and to 57% for patient 9 (Table 2). Both of these plans achieved 100% coverage of the iCTV after resimulation and replanning. Neither patient had local failure. One consequence of improving the tumor coverage for patient 9 was a higher esophageal V70 (Table 2); that patient developed grade 1 esophagitis. The two local failures experienced in the adaptive group occurred within the 100% isodose line throughout treatment.

Toxicities

Toxicity rates for the entire group are published elsewhere (2). The overall rates of toxicities related or possibly related to radiation were slightly higher among patients treated with adaptive plans than for those treated with non-adaptive plans, but the overall number of events was low. Specifically, 5 patients (2 adaptive, 3 non-adaptive plans) experienced grade 3 dermatitis; 5 patients (2 adaptive, 3 non-adaptive plans) had grade 3 esophagitis; 1 patient (adaptive plan) had grade 3 pneumonitis; 2 patients (1 adaptive, 1 non-adaptive plan) had grade 3 dyspnea; 1 patient (adaptive plan) had grade 3 cough; 1 patient (non-adaptive plan) had grade 3 pleural effusion; and 1 patient (adaptive plan) had grade 3 pulmonary/pleural fistula. No patients experienced radiation-related grade =4 toxicity, but 3 patients had chemotherapy-induced grade 4 hematologic toxicity (Table 3) (2).

Table 3.

Toxic effects related to or possibly related to radiation therapy

| Type of adverse effect | Treatment group and toxic effect grade

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |||

|

| ||||

| Adaptive | Non-adaptive | Adaptive | Non-adaptive | |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Anorexia | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophagitis | 2 | 12 | 2 | 3 |

| Esophageal stricture | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Dehydration | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Respiratory | ||||

| Dyspnea | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Cough | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Hemoptysis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Atelectasis | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pulmonary/Pleural Fistula | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Other | ||||

| Pain | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperpigmentation | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatitis | 5 | 14 | 2 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 4 | 7 | 0 | 6 |

DISCUSSION

Technological advances have allowed investigators to analyze whether adapting radiation plans for lung cancer can improve outcomes. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to describe failure patterns, outcomes, and toxicities for patients who were treated with adaptive proton radiation plans. Although our patient numbers were small, we found no significant differences between rates of local failure, regional failure, distant failure, overall survival, or toxicities at 2 years between patients who had been treated with adaptive plans versus non-adaptive plans, even though patients with adaptive plans tended to have larger tumors. Our findings lead us to recommend that patients with an iGTV of about 100 cm3 who also experience a 25% or greater reduction in that iGTV within the first half of the treatment period be considered for adaptive planning. The methods described here may help to guide adaptive planning for proton radiation therapy and serve as the basis for future dose-escalation studies.

One major question about adaptive planning is whether changing the radiation plan will affect clinical outcomes. Indeed, our group previously showed that tumor coverage can be compromised by changes in tumor volume and density during radiation treatment (12), but the clinical significance of this observation was uncertain. With the advent of image-guided radiation therapy, the issue of whether to treat a smaller volume if the lung tumor shrinks has become controversial (7), in large part because of concerns about residual microscopic disease. Notably, we saw no regional failures (i.e., no marginal misses of the target) in any patient receiving adaptive therapy. Because the regions receiving high doses modified during the adaptive portion of the plans, it seems that any microscopic disease either (1) regressed with the iGTV or (2) remained the same but was sterilized despite the changed plan. Moreover, the median number of adapted fractions was 13; hence during the first 24 of 37 fractions, at 2 Gy(RBE) per fraction, any microscopic disease would have received at least 48 Gy(RBE) in half the adaptive plans. This dose might be considered sufficient against microscopic disease, but longer follow-up with additional patients and further clinicopathological correlation will be necessary to confirm this supposition. We also observed that all local failures among the patients with adaptive plans were within the 100% isodose line throughout the treatment, indicating that those tumors were resistant to chemoradiation. Because we found no differences in local or regional failure rates between patients given adaptive versus non-adaptive plans, the methods used to adapt the proton radiation plans likely did not compromise tumor coverage.

Proton radiation is quite sensitive to alterations in the position and density of tumors (12), and thus such changes must be accounted for over the course of treatment. The major considerations for determining whether patients need resimulation or adaptive planning should include the initial size of the tumor and the extent to which it responds during treatment, as these were the major differences between patients who received adaptive plans and those who did not (Table 1). Another consideration may be the extent to which tumors regress away from critical structures. In our study, patients who did not receive adaptive plans showed only minimal changes in tumor volume and location upon resimulation.

The methods used here typically decreased the penetration of the beam so that doses to normal structures distal to the tumor target did not exceed tolerance limits and so that the prescribed dose of radiation covered the iCTV. One of the simplest ways to adapt plans was to maintain the same beam angles and the same or a similar aperture, calculate the necessary beam energy and range, and create a new compensator for the changed tumor target. This approach can be implemented relatively quickly. The dosimetric characteristics of the adaptive plans improved over a wide range of fractions (4–22), indicating the need for individualized treatment planning, particularly for patients with large thoracic tumors.

If the changes in the tumors had not been accounted for through adaptation, we believe that toxicity rates likely would have been higher. We observed that dermatitis, dyspnea, and esophagitis were the most common grade 3 events for patients who received adaptive plans. In 1 case, the V70 for the esophagus would have exceeded 40% without adaptation. This patient was 1 of 2 who had adaptive plans and experienced grade 3 esophagitis. In 3 cases, the maximum dose to the spinal cord would have exceeded 45 Gy(RBE) without adaptation. In several other cases, lung dose limitations would have been exceeded without adaptive planning. Pulmonary grade 3 toxicities were more common in the adaptive-plan group than in the nonadaptive-plan group; although the numbers of patients in these groups were small, one might speculate that toxicity rates would have been worse if adaptive planning had not been used. Possible solutions for minimizing pulmonary effects may involve use of respiratory gating techniques or more frequent assessment of tumor response during treatment (with adaptation, if appropriate). The overall low rate of grade 3 toxicities for the adaptive-plan group indicates that the therapy is well tolerated and can produce outcomes comparable to those for patients with non-adaptive plans.

Certainly this study was limited by its retrospective nature and the small number of patients, and as such our results must be considered preliminary and prospective validation of the adaptive radiation techniques will be required. Another consideration in adaptive planning includes the possibility of selective dose escalation to radioresistant subregions within the tumor (16) based on their biological responses to therapy.

In conclusion, we propose that the use of adaptive planning may improve coverage of the target volume and sparing of normal tissue structures in combined chemotherapy and proton radiation therapy for NSCLC, particularly for patients with large (100 cm3) thoracic tumors that regress significantly (by 25% or more) during proton therapy. The methods developed here may help to guide future prospective trials using adaptive proton therapy and radiation dose escalation.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY.

Adaptive planning entails modifying a radiation treatment plan during the course of radiotherapy to account for changes in patient anatomy or tumor characteristics that can significantly alter the dose distribution, particularly that of protons. We found no significant differences in toxicity, local control, regional control, distant control, or overall survival for patients who had or had not had adaptive planning during concurrent high-dose proton therapy and chemotherapy for stage III lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Thoracic Radiation Oncology, Proton Therapy Center, and Thoracic Medical Oncology teams and Ms. Christine Wogan of the Division of Radiation Oncology at MD Anderson for their help and support.

Dr. Chang is a recipient of a Developmental Project Award from The University of Texas National Institutes of Health Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) (P50 CA70907). Other funding included National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA74043, P01 CA021239, and CA016672.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schwarz M, Alber M, Lebesque JV, et al. Dose heterogeneity in the target volume and intensity-modulated radiotherapy to escalate the dose in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang JY, Komaki R, Lu C, et al. Phase 2 study of high-dose proton therapy with concurrent chemotherapy for unresectable stage III nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011 Mar 22; doi: 10.1002/cncr.26080. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang JY, Komaki R, Wen HY, et al. Toxicity and Patterns of Failure of Adaptive/Ablative Proton Therapy for Early-Stage, Medically Inoperable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(5):1350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang JY, Zhang X, Wang X, et al. Significant reduction of normal tissue dose by proton radiotherapy compared with three-dimensional conformal or intensity-modulated radiation therapy in Stage I or Stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1087–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Li Y, Pan X, et al. Intensity-modulated proton therapy reduces the dose to normal tissue compared with intensity-modulated radiation therapy or passive scattering proton therapy and enables individualized radical radiotherapy for extensive stage IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer: a virtual clinical study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthelsen AK, Dobbs J, Kjellen E, et al. What’s new in target volume definition for radiologists in ICRU Report 71? How can the ICRU volume definitions be integrated in clinical practice? Cancer Imaging. 2007;7:104–116. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2007.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang JY, Dong L, Liu H, et al. Image-guided radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:177–186. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181622bdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez DR, Chang JY. Adaptive Radiation for Lung Cancer. J Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/898391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosmans G, van Baardwijk A, Dekker A, et al. Intra-patient variability of tumor volume and tumor motion during conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective clinical study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:748–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox J, Ford E, Redmond K, et al. Quantification of tumor volume changes during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott LN, Wendling M, Sonke JJ, et al. Anatomy changes in radiotherapy detected using portal imaging. Radiother Oncol. 2006;79:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui Z, Zhang X, Starkschall G, et al. Effects of interfractional motion and anatomic changes on proton therapy dose distribution in lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1385–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelsman M, Rietzel E, Kooy HM. Four-dimensional proton treatment planning for lung tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1589–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang Y, Zhang X, Chang JY, et al. 4D Proton treatment planning strategy for mobile lung tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:906–914. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moyers MF, Miller DW, Bush DA, et al. Methodologies and tools for proton beam design for lung tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang JY, Cox JD. Improving radiation conformality in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.